Holes Concept/Vocabulary Analysis Literary Text: Holes by Louis

Function of Keys-Opening and Closing Tone Holes

-

Upload

marco-guimaraes -

Category

Documents

-

view

42 -

download

3

Transcript of Function of Keys-Opening and Closing Tone Holes

The Key System

Function of Keys: Opening and closing tone holes

When comparing a modern clarinet and a recorder, the first thing that obviously is

different (next to the colour of the wood and the size) is the clarinet's key system.

It looks rather complicated and that is in fact the case. Short and long levers,

blocks, axes and tubes move long and short keys, having pads in the end. Some

even interact in complex ways.

For somebody who does not play the clarinet (or the oboe or bassoon which

have got a very similar system), it appears to be confusing, and many players,

too, couldn't definitely say which keys would go which way when they play a

certain note. We players have just learned how to do the fingering, and we do

that now without much thinking about it.

You need the clarinet's keys in order to do what you can do on the recorder just

using fingers: Opening and closing the toneholes.

In order to work properly, a key must close the tone-hole completely tight - when

closed, no air should go through it. It should give as little resistance to the air flow

as possible when open - this requires a key-pad to open to a distance that is at

least a third of the diameter of the tone-hole. Then keys must open and close

quickly - that is really quick; and for both directions: One move is done with your

finger, usually this is no problem, but then a spring has to put the key back into

exactly the same position it was before. Don't forget that some keys open AND

close different holes at the same time - and some levers are long! Bass clarinets

have got mechanics that move pads about half a meter away. This requires

springs to be strong and the axis to have as little friction as possible.

Pads must work wet and dry, make no sound of themselfs and must be extremely reliable. They

must be acoustically neutral, too, that is, they must not influence the instrument's sound. Your

own fingertips would do all that - and thinking about that, it becomes a challenge to beat fingertips

when it comes to closing tone holes. Wind instrument builders of all times had to find ways to

solve this.

As we discuss it, you will find there are indeed "fingers only" solutions at least when closing upper

tone holes, when playing the smaller clarinets like Eb-flat and B-flat. But you can't do this with all

holes for three reasons:

1. because the limited hand span is not enough to cover the whole clarinet,

2. the larger tone holes should be large, too wide for normal fingers,

3. (and most importantly) you would need more than ten fingers to operate the instrument - I will show you why further down; and this is unique with clarinets.

Contents

Tone holes - too far away and to wide for fingertipsWhy does the tone become higher when opening a tone hole?Clarinets must have more tone holes than other wind instrumentsPlay higher registers: Overblowing with the speaker holePlay half tones by forkingLowering tones by "covering"Play half tones with additional tone holesOpen and closed keysRequirements keys must meetKey development in historyModern tone holes: No simple drill jobKey materialsPadsSpringsKey differences Boehm vs GermanKeys and accousticsSome thoughts about optimal keys

Tone holes - some are too far away and too wide for fingertips

The smaller members of the clarinet family, the E-flat and the B-flat, do have simple tone holes

that you can close with your finger tips, much like a recorder. But even with the smaller

instrument types the lowest holes - that are way down - cannot be closed with your fingertips

only. The larger the instrument, the further away the tone holes. And you will see that tone holes

for lower tones are wider than your fingertips, which is acustically helpful.

In modern clarinets, some of the key mechanics are designed to close tone holes at places where

a finger couldn't go easily. You want to have the tone holes at the optimal position rather than

drilling them where they can be used based an average player's anatomy. Optimal positions

would be a straight line down facing the audience, including the thumb-operated speaker key, a

hole that usually faces the player.

Why does opening a tone hole change the tone?

Simplified: When playing, the air column in the bore swings - comparable with a guitar string;

and this swinging is passed on to the surrounding air, which in turn reaches our ears and can be

heard as a sound. When the guitar player makes the swinging string shorter by pressing the

string down, its swinging movement becomes shorter (because the speed of swinging itself

remains) and a shorter swinging translates into a higher frequency, so the tone becomes higher.

When he moves the finger further up, the swinging part of the string becomes longer again, the

tone becomes lower.

Practically this means: Half the length of a string = doubled Frequency = an Octave higher.

This is practically the same with wind instruments, only that there is no up-and-down-swinging

string, but a forward-and-backward-swinging pressure wave in an air column within the

instruments body between mouth piece tip and the opening at the bottom (making things a bit

more difficult to watch and understand). Bends within the instrument show little influence to this

as long as the diameter of the bore is not affected, so larger clarinets (Alto, Bass, Contra) and

bassoons have bended shapes, which helps handling them. The complete length of the swinging

air column depends on the length of the instrument as such - as long as all tone holes are

covered. The moment that one tone hole is opened (and if it is wide enough to let most of the

swinging air column stream out of the instrument's body), the length of the swinging air column is

reduced to roughly the distance between the reed's tip and the tone hole. So - simplified - when

you open a sufficiently large tone hole this means nearly the same as reducing the instruments

overall length.

Clarinets have to have more tone holes than other wind instruments

In order to understand the tone holes and keys of a clarinet, let us at first take a look at the much

simpler design of the soprano recorder, that has no keys at all and (usually) eight tone holes.

Many people have learnt to play this simple wind instrument as first instrument in school. Of the

eight tone holes seven are on the front and one - the speaker hole or octave hole - is on the back

where you have your left thumb. With this instrument you can play all notes of an octave. The

lowest not - C - sounds, when you blow into the mouthpiece with all holes are closed. When

opening one tone hole after the other starting from the bottom one you have a scale in C:

C - D - E - F - G - A - H (or B-sharp) or in romanic cultures: Do - Re - Mi - Fa - So - La - Si.

Scale on simple recorders - for better instruments fingering may be different!Seven tone holes at the front - the octave- or speaker-hole is the circle at the side.

Black = closed / white = opened / half = half openedIn some countries the "H" is called "B-sharp"

You can play the high c and d via "forked fingering", this will be explained below.

Play higher registers: Overblowing with the speaker hole

When you open the overblowing - hole (speaker hole) half way (with your left thumb) and play the

same scale, the instrument produces the same notes, but exactly one octave higher.

One octave higher equals eight notes on the scale and this means a doubling of the frequency.

For us it appears to be the same tone, just higher. A C remains a c, a G remains a g. And

fingering is very simple because of that - you use the same fingering for the notes in the upper

and lower register.

In order to make the speaker hole work as such and not as an ordinary open tone hole, that

would result in a very sharp high tone, the overblowing hole must be much smaller than an

ordinary tone hole. Recorder players reach that by half-covering the hole. What it does acustically

is "destroying" the lowest frequency of the flute sound, and only the overtones (octaves and

multiples) remain, resulting in the higher tones. These were present in the low register, too, but

not so dominant (see overtones).

As said above: If the overblowing hole was too wide, the swinging air column would exit the

instrument here as it would with every other tone hole, and this very high tone would remain,

independently of what holes below were closed or opened. Therefore the overblow- or speaker-

hole is very narrow (clarinet, oboe) or you only open it half (recorder).

The switch into the octave when opening the overblowing hole is the same not only for recorders,

but all other wood wind instruments like saxophones, bassoons oboes. The clarinet is the

exception to the rule: It has got an overblow hole much like all other woodwinds, and it works the

same way, but when opening this hole, the frequency is not doubled, but it becomes 2.5 fold. In

notes on a scale, this is not the 8th, but the 12th note (because doubling means the 8th note on a

scale, 2.5 - which is doubling plus a half is 8 plus 8/2 = 8 + 4 = 12). In Latin this is called

duodecime: octava means 8th, duodecima (~dozen) means 12 .

Above I have mentioned that opening the overblowing-hole the lowest frequency, that is the one

that we hear conciously, is destroyed, while the next higher strong frequency can now be heard

prominently (and all others remain intact as well). The sound of an instrument or voice does not

only consist of one frequency, but a row; which are connected in a mathematical relation; usually

- with recorders, oboes, saxophones and most other wind instruments like 1 : 2 : 4 etc. - this are

even numbered relations.

But with a clarinet - for acoustical reasons - the relations of the sound waves produced are

different, they create waves in relations like 1 : 3 : 5 and so on, so they are odd numbers.

Mathematically 8 : 12 is the same as 2 : 3.

So now when you use the fingering for a C and open the overblowing hole on a clarinet, what you

hear is not a high c, but a g. So far so bad. A scale and a fingering chart for a clarinet now looks

like this:

simple clarinet without holes for half-tones

In some countries the "H" is called "B-sharp"

In practical life this means: The most simple clarinet with tone holes for just a scale in the key of

C with no #-sharps or b-flats needs more tone holes than a recorder, because where the recorder

already plays the eigth note of the scale with the fingering for the first; the clarinet needs

additional tone holes for the note 8, 9, 10 and 11. So you need at least 10 tone holes plus an

overblowing hole; adds up to 11 holes. And in real life you need at least one finger (usually the

right hand's thumb) to hold the instrument, even when it is placed on the ground like a bass

clarinet. That means you only have 9 fingers to operate 11 holes. In result that means in order to

build a clarinet, you need at least two keys.

That is what you find at the first clarinets: Zwei Klappen, a long one for the lowest note, and an

overblowing or speaker key. Because we have to operate the instrument and its 11 holes with 9

fingers, some fingers have to do doulbe function jobs.

Creating half tones - method one: Forked fingering

Some wood wind instruments - like the recorder - will produce a pleasant scale in every key with

simple fingering, like shown above. But with a scale in C you can't play much more than the

simplest of children's songs - they need half tone steps, let alone classical music in several keys.

So the recorder uses forked fingering - and most old wood winds do it the same.

If you now want to play a G-flat - which is half a tone lower than G, you use the fingering for G

and close the tone hole not one below, but two below, leaving the hole one below G open. This

results in a quite well tuned G-flat.

Why is that - and why does this not produce a mixture between a bad G and an E, as you might

have expected?

The swinging air column now exits out of the open (forked) tone hole, in our case the F-hole, but

only partly. Below the tone hole but still within the bore it continues to swing, but now we have an

air column consisting of two parts, that is related via a knot, just behind the opened tone hole.

The lower (smaller) part continues down to the D-hole. Physically speaking this is being added to

the existing column for about half the distance between forked hole and open hole. That

produced that surprisingly well tuned G-flat.

Now forked fingering works only as long as the forked hole is not too wide, very much like the

overblowing hole. Otherwise the air column would be exiting the instrumen fully and we would

have a badly sounding (too low) F. In order to prevent that, players sometimes half-cover the

forked holes, or the designer has build special ring keys for this purpose.

Lowering tones by "covering"

If you cover further tone holes below, for example the D-hole, the tone will sound even lower. It is

the same effect as with forking, and it works as long as the number of tone holes you leave open

is not to large (two, up to three open holes may still work). So this helps you lowering otherwise to

high sounding notes. Many players will find that the tuning of their instrument becomes higher in

ppp than in a solid forte, and this technique may be more reliable than changing the tuning with

the embouchure. Of course this may reduce the sound quality somewhat, so you have to find a

compromise, but then - compared to being not in tune in a unisono-passage with a flute - the

sound quality may be less important to you...

Create half tones with additional tone holes

Forking works, and it works well, especially in practical playing. Nevertheless it has its

disadvantages: Toneholes, that you use for forking, must not be too wide, because otherwise the

swinging air-column will "break out" of the instrument and there will be no swinging node (and this

may depend on the hight of the tone, the loudness, the tone you played just before etc. etc.). But

a smaller tone hole has its disadvantages, when it is used as a normal tone hole; then it should

be as wide as possible. Because that is difficult to construct, the instrument builder will allways

settle for compromises, but those are often unfortunate and all this will make forking less than

optimal.

We have now learnt that the classical tone hole is not only "open" or "shut", there is a third state:

"reduced". Every recorder player knows that. Now you can understand, too, why the overblowing

or speaker hole is so small - you open it only as far as necessary to let a part of the swinging

wave break out (lower frequencies) and another part go on within the bore. And that is why some

clarinets have got keys that have a very small hole drilled into the key and pad - that is in order to

produce a "half open" state, for example for the high "c".

Unfortunately the size of tone holes depends on the register, because the acoustical impedance

becomes more prominent the higher the frequency is. In the clarinet register forking works less

optimal than in the low chalumeau register.

In consequence modern clarinets use for nearly all half tones extra tone holes, and forking is

reduced. There are even mechanical tricks that let the player fork, but the mechanic translates

that into opening a tone hole instead. All this results in five more tone holes per octave than a

recorder has got:

C - C# - D - D# - E - F - F# - G - G# - A - A#(B) - B#

This corresponds with the black keys on the piano keyboard (for 8 white ones you have 5 black

ones). Because the clarinet has not only got an octave per register, but a duodezime, that is 12

tones, there must be 7 more holes; that is: you have got 7 more; there are at least 19 tone holes

(if the lowest and topmost tone is the same):

E - F - F# - G - G# - A - A#(B) - B# - c - c# - d - d# - e - f - f# - g - g# - a - a#(b)

Adding the overblow hole, you can forget wanting to close all those holes with fingers only! Even

my simple student model soprano clarinet (German model) only the speaker key had no key. And

then it has got a lot of resonance- and improvement keys. Between 22 and 28 keys are standard

for the German system, the Boehm has got some 20 keys and 5 rings.

Open and closed keys

When you examine a clarinet (or other woodwinds) you find that they have open and closed keys;

that is, some open a tone hole when you press them and some close a tone hole. Open keys are

the same as tone holes on a recorder: You would close them with you finger, but here you have

got a key for that. But what are closed keys good for? Why would you need keys that open a tone

hole when you press them?

In the first place closed keys are used for half tones (C#, D#, F# etc.) - on a piano keyboard that

would be the black keys.

Certain closed keys are good as alternativ way to open keys (jumps and tremolos) or for

correcting the tuning. They sometimes open automatically, when pressing down other keys.

Requirements keys must meet

Keys must make sure that

tone holes can be closed perfectly: When closed a key must not let any air escape the instruments body through the tone hole

tone holes are fully open and impose no acoustical impedance for the streaming air, this is achieved by chosing the largest possible diameter of the tone hole (and the key); plaus the key must go up at least a third of the tone hole's diameter. If the lowest key that is actually open is not far away enough from the tone holes surface, then the tone will not sound well or even be significantly to low. This is the same as the covering technique desricbed above.

opening and closing of keys must be quick - that is especially critical in the case of the open keys - the ones that are opend by pressing with a finger and closed by a spring pressing the pad back onto the hole. The force of the spring must be sufficient to work quickly and there must be no friction in the bearing.

And then, too, keys must not click, squeak - they should always work completely silent.

All this can be achieved rather well using modern keys and frequently maintaining them.

Keys development in history

The clarinet's key system (this is of course very similar to the oboe's and somewhat similar to the

flute's) is an ingenious achievement which improved over hundreds of years. With it you can

close and open the tone holes wherever they are quickly and without causing irritating sounds.

Historical key with felt pad

Early keys were far from perfect and simply a prolongation for the fingers to reach holes too far

away; they were metal levers with a piece of felt glued to a square end. This type of key was - of

course - never perfectly tight, and obviously only worked when the felt was damp. A key with a

flat pad made it necessary to sand the surface around the key hole flat, and those tone holes

were relatively small.

The first major step which made the modern clarinet possible was the invention by instrument

builder Iwan Müller who invented the "salt-spoon-key". In connection with the sunk in key hole the

new key could close holes nearly perfectly. His design is the one we still use today. We will look

at the improvements in detail below.

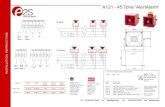

Different types of modern keys: salt-spoon-keys, ring-keys

The second essential improvement was the ring key by Klosé. A "ring" is a key with an opening -

shown on the photo next to the forefinger. With a ring key you can close holes that are in reach of

your fingers but since this enhances the diameter of your fingers, the holes can be drilled to the

acoustically optimal size (which you could not close with fingers alone).

After this there came numerous steps that you can sum up as mechanical connections between

keys that make trills and jumps possible that otherwise would have been very difficult or

impossible. However, the key mechanic also adapted to the habit: For example one still grips

forks while the key mechanic turns this into an acoustically better result.

Modern tone holes: No simple drill job

simple hole

sunk-in hole

You hardly find any tone holes in your clarinet that are similar to the ones of a recorder - on the

picture left it is the upper tone hole. These are the ones that you have to cover with fingertips, All

other tone holes, that are covered by keys with pads, look differently: They are sunk-in, that is:

they are in a bowl-shaped indention and the hole itself is surrounded by a ring-shaped border

with a sharp edge. The lower tone hole on the picture is one like that.

Sunk-in tone holes are necessary, because the surface of the simple tone hole is not flat but bent

- like the surface of the clarinet's body. With a flat pad you cannot close a tone hole that is the

result of a simple drill job. Producing a perfectly fitting bent pad that has exactly the shape of the

clarinet's body would be possible today, but still a sunk in hole would be much better for use and

makes the key maintenance simpler.

The most simple and practical solution was to make the surface around the tone hole flat - that is,

what Denner and other early instrument makers did. You can see it on the picture of the ancient

key above. But to close a tone hole with a leather pad, a ring-shaped border around the hole is

suited much better than a flat surface: The sharp edge will press into the soft surface, making it fit

even better. The key with the soft leather pad will close the tone hole even if the pad is not

aligned perfectly. In order not to carve out too much material, the instrument maker only sinks in

a flat bowl-shaped area around the tone hole (about 2 mm or 1/10 inch).

Key materials

Key - pad - blocks

In general the metal parts of the key system consist of German silver cast parts. That is a copper-

based alloy. When long turning keys are made, steel tubes are soldered onto the keys, usually

using silver lead. Really expensive instruments have forged keys which are less prone to

breaking than cast keys (and then again hand-forged are better than drop-forged, where a huge

weight falls onto the metal to forge it into form). Since all these metals can be soldered with silver

lead, they can be repaired easily. Most clarinet's metal parts are silver-plated, some are nickel-

plated or gilded. This is done in electroplating baths. The coating materials have pros and cons:

Silver - the most common - looks nice, but may tarnish, primarily in contact with sweat

Nickel doesn't tarnish, is durable, glides well, is cheap, but unfortunately Nickel can trigger allergies (this is quite frequent - so you better keep your hands off Nickel!)

Gold does neither tarnish, is good for gliding, but expensive and looks unusual (could be problematic in case a uniform look of instruments is favorable, because there are frequent TV performances ;-)

Pads

Clarinet pads are traditionally made of leather, felt and cardbord, but today you find silikon (the

elastic material), too, sometimes cork and more recently other synthetical material.

Leather pads

Traditional pad (leather coating, felt, cardboard)

Leather pads have dominated for hundreds of years, and are still more practical than most other

types. They are made of a round cardboard plate as base (in the picture the cardboard is the

bottom part) and a felt plate (in the middle) of the same size. Over that the manufacturer fixes a

thin, soft leather coating. Originally that was a fish skin (flutes still use that). The leather is usually

died white for clarinets, and is golden brown for saxophone pads. That type of pad can be bought

in all sizes even in not so specialised music shops - they are the same for clarinets, saxophones

and oboes. What matters is the strength and even more the diameter.

Leather pads do have advantages: They work well, they are usually tight, and they tolerate slight

imperfections of the key because - when becoming wet - they will adapt to the tone hole again.

The sharp ringshaped border of the sunk in hole will press in into the soft moist leather. Leather

pads are easy to fix onto the keys and they can be removed as easily. You use seal wax (the

traditional way) or hot-melt glue for this. You find a "how to" under Repair / First Aid.

The main problem is that slowly start to sound bad when getting too old - the leather then gets

brittle. Then, at the latest, you have to change the pad or have them changed. The more frequent

a leather pad gets wet, the sooner this will happen. That means that the pads high up on the

clarinet usually have to be replaced more often than the ones down that hardly ever will need

that. As a rule of thumb it is good to have your instrument maintained once a year if you play

much (like 5 - 10 hours a week) or every second year if you play less; and that is when the upper

pads should be replaced.

Silicone padsToday you will find a lot of pads are made from elastic silicone, similar to what is used to glue

tubes to your bathtub or sticks sheet glass together as an aquarium. Silicon has got advantages:

It can be brought into every form, is elastic and does not change under humidity. It will last and

stay in form forever (that is: longer than your clarinet's body) - so it never will have to be changed.

The advantage is a disadvantage at the same time: It will not change its form; so if the key is bent

a bid, then the pad will not be placed perfectly over the tone hole and will fail to close the hole.

Sometimes it will still do as long as its surface is still wet, but when it dries a bit, it will no more. A

leather pad would adapt itself and you wouldn't even notice. Some musicians think that the tone

will be influenced negatively - but serious tests have found out that in the long run the majority of

listeners will prefer the sound of a clarinet with silicone pads to one with leather pads (except

when the leather pads are new, not much older than a couple of months - since they do degrade

quickly).

Besides issues with bent keys there are two more disadvantages that silicon pads have:

since silicon does not stick to most materials after it has "hardened" you can not easily glue a pad that has fallen out back into place, especially not if this happens just before a concerto. You can, too, glue in special silicon pads with thermo glue - so we can expect to see this become more frequent. Another solution are silicone pads that have a base made of a different material, onto which the glue is then applied, which will make standard procedures the same as with leather pads.

since silicon does not absorb water, the quantity of water on the clarinet's wooden corpus that is covered by the pad can not evaporate except through the wood. That is it will stay there for a long time. That may cause serious problems for the tone hole if you store your instrument away without having wiped it out fully.

Cork padsCork pads are still used where a leather pad would be unpractical - and where you expect a lot of

moisture like the duodezime-key on the bass clarinet. Cork is not bad as pad material, easy to

repair, easy to handle, but it is not fully elastic - slowly but surely the material becomes and

remains compressed. It probably will be fully replaced with silicon in the future.

Innovative padsMost of the new developments like the silicium resonance pad are acustically superior to most

pads that exist today except for new leather pads. But they require extremely precise keys that

must not bend easily (because the pads are neither very elastic nor do they adapt) and they need

sharp and precisely inlet key holes. This is not always given with your standard clarinet today

(except for very expensive models).

SpringsAll keys use springs, either to open the key and keep the key open when not pressed or to close

it when released - depending on the function of the key. They come in two technical types:

the sheet spring and the needle spring.

Flip key with sheet spring

The sheet spring is most widely used with flip keys. It consists of a flat sheet of hardened spring

steel, that is screwed against a key. The other end usually presses against the instrument's body.

Pivot key with needle spring

Needle springs, are most often used to turn a key on an axis. The needle is fixed to a column

and presses against a hook soldered to the key. They actually used to be made of sewing

needles.

Both types work fine, are simple and robust and can be adjusted with simple tools like a

screwdriver and pliers. If you bend the spring further in the direction it presses, the power of the

spring increases. If you bend it into the other direction the power is reduced. This can be done a

couple of times, anyway, be careful not to break the spring - even if you can replace the needle

by an ordinary needle from a sewing set, you will have a hard time finding a fitting one, you can't

bend it into form easily and then you won't be able to fix it in the column without help of an

experienced instrument maker (let alone the sheet spring - you won't find that in hardware

stores...)

How the keys affect the accoustics and intonation

When keys are open, they would ideally not hinder the stream of air to go out of the instrument at

all. It would theoretically be even ideal if the clarinet ended somewhere on the upper edge of the

tone hole (like it would be virtually sawed off here). But, however, the key has considerable

influence on the flow of air even when it is fully open - that is easily shown: Do open a ring key by

moving your fingertip up for a couple of millimeters and swing the finger up and down. You can

hear the effect, but you can even still hear a bit of it if you do the same more than two centimeters

(nearly an inch) away from the opening, and of course no key opens that far. This is true for all

keys. The position of the key pad has considerable influence on the correct intonation of the

instrument. Of course the instrument maker has taken this into account. The tone holes are

always drilled a bit further up the instrument's body (towards the mouthpiece) than they would be

without this effect. The position of the hole should be correct if one considers a key to have a

leather pad which has a distance to the hole surface that equals a third of the bore diameter

when fully open. Change the parameters (different material, different distance) and you might get

different results.

Differences in key systems: German vs. Boehm

German / Boehm

There are some more and some less obvious differences between Boehm clarinets and the

German system. This chapter discusses only the key and mechanics aspects. You find a

discussion of the systems as such here.

Since you do not speak German (otherwise you should be reading theGerman version of this

website) you are probably used to Boehm systems (except if you are living in an oriental or a

Jazz culture, where an old-fashioned type of the German instrument is used). So what you know

is the clarinet on the right. The most obvious different feature that you can even see from far

away are four levers for the little finger on the lower joint of the Boehm instrument, whereas the

German system has got two wide, silverplated flat fingerrests with Ebony rolls to slide forward

and back.

Another important difference in keys are the very long flip-keys that the German system has in

the lower joint. They reach from top of the joint to the lowest key, and often even to a resonance

pad on the bell. You operate them with your little finger of the left hand. The Boehm system has

replaced those long keys by rotating tubes. That is a significant improvement, because if

something breaks on a German clarinet, it is those long flip levers!

Especially when building long levers the combination of needle spring and rotating tube is much

more durable, makes less noises and needs less space. Furthermore it will be more reliable

when playing. In order to avoid breakage some German instrument desingers combined a chain

of flip keys, again not so great, because they react sluggish because of the joints. A rotating tube

of steel can be quite long and still works precisely.

The latest German style designs replace the long flip keys by turning tubes, wherever possible,

and that is especially true for the long keys that bass and contra bass clarinets use. The goal is to

make it practical, fast, quiet, but conserve the traditional fingering as far as possible.

The fingering that you use for Boehm instruments mostly avoids "gliding" of fingers from one key

to another, especially that of the little finger (which is important for German instrument). Because

Jazz players, Oriental and Klezmer players seem to prefer exactly that (it improves the sliding of

notes, too) many have kept the traditional instrument and not switched to Boehm, although their

classical neighbors have.

Being German myself I have, of course, learnt to play the German system. Today I play a Boehm

Bass Clarinet, and comparing the fingering, the Boehm system has got some more advantages

than it has disadvantages. There are some more alternative fingerings for the same note, that

means, some difficult parts (jumps and trills) can be played more easily, as well as a legato is

easier. However, I would not recommend a German who is getting along well with the instrument

to change to Boehm just for that reason.

There might be one more point, here, too: For people with small hands and short fingers the

Boehm system seems to be a bit easier to handle than the German system.

Some thoughts on optimal keysJack Brymer has stated in his excellent book (by the way: a "must read") that the clarinet key

opens the tone hole in the wrong place, and he is right: Ideally it would close the tone hole inside

at the bore, in order to leave a shining, polished, uninterrupted tube with nothing causing air

turbulences. When the tone hole is open, the opening should be as big as possible. The key

should open and close the hole in an instance extremely fast and fully wide - much like a camera

shutter. Since instrument builders and clarinet players are conservative, this may be only

theoretical thinking, but from time to time you find revolutionaries in this metier, and

micromechanics and electronics have advanced in recent years, so it may be technically possible

E Flat Clarinet

The smallest common clarinetThe E flat clarinet is the smallest of the standard clarinets, about a third shorter than the B flat-

or A-clarinets. It is noted in E flat, which gives it its name. The notes are noted in the violine key

and fingering is the same as on a B flat clarinet - except that everything is a bit narrower.

Most e flat clarinets produce a sharp, sometimes shrill sound. In symphonic works the instrument

is usually set - because of its tone range - unisono with flutes and oboes (which often means wild

acrobatics in extreme hights) and it is often not easy to be exactly in tune with an E flat clarinet.

Especially not unisono with flutes - when warming up they show different behavior concerning

tuning than clarinets, so you must frequently re-tune.

Quite often - and generally in amateur bands - a "normal" clarinet player does play the E flat

clarinet in addition to playing a first clarinet; and more often than not that will be a simpler, that is:

less expensive instrument (since the industry produces less E flat clarinets than B flat clarinets

the instrument is rather more expensive).

Combined with the challenges both in technical and intonational problems this is a very difficult

task. In my symphonic wind band the E flat player is usually the one clarinet player with the best

"ears" and excellent technical abilities.

Tough on your lips - and how to cope with itThe considerably smaller and narrower mouthpiece and reed presses harder on the lower lip than

that of the B flat clarinet. In order to prevent biting into the lower lip, many E flat clarinet players

put a piece of thin leather over the lower jaw.

Short keys - but nothing for kids or beginnersThis instrument is a challenge for people who already play even the most technically challenging

parts with ease, and have got excellent hearing - maybe a good alternative to becoming the first

clarinet player in an existing orchestra. This instrument is not a kid's clarinet and not suitable for a

beginner! Kids should better wait until their hands are big enough for a B flat instrument.

A and B flat clarinets

The "Normal" Clarinet

The A clarinet and the B flat clarinet are the "normal" clarinets. They are the ones that you

usually think of when you talk about "the" clarinet. Sometimes this clarinet is referred to as

"soprano clarinet" (which is correct, thinking of clarinets resembling the voices Bass, Alto and

Soprano).

B flat - by far the most frequently usedOf the two soprano clarinets the B flat clarinet is by far the most frequently used instrument - both

in the wind orchestra and in jazz there are no A clarinets any more. The A clarinet is still widely

used in classical music. The classical clarinet player carries about a set-case containing both

instruments. There are many pieces where you have to use them both, depending on the key of

the part that is played.

What Are A Clarinets Good For?

Of course one could - theoretically - transpose the notes, you probably would prefer to write the

notes down. But in reality that turns out to become very difficult for the player, since most keys

and a lot of jumps can't be executed so easily and as result the piece would sound much poorer

than it would have to. If you plan to play the famous clarinet concerto in A by Mozart on a B flat

clarinet, that will translate into B (Si) - which means five sharps (as opposed to none for the A

clarinet).

Very handy: One Bore Diameter - One MouthpieceThe A and B flat clarinet are very similar in size (only half a tone apart) and both have the same

bore diameter - so you will use only one mouth piece for both instruments. That means that you

can quickly change from A to B flat having a warm mouth piece with an already played-in reed,

considerably reducing the risk of squeaking. One thing less to worry about! And of course you

don't have to buy a second mouth piece and different reeds.

Bassett ClarinetDespite its name the modern Bassett Clarinet is not a Bassett Horn but rather a soprano A

clarinet (very rarely a B flat) that was extended by about 18 cm towards the bell and four extra

keys. That means the tone range is extended four half tones (E flat to C). So it becomes possible

to play Mozart's clarinet concerto KV 622 in the original form without the transposed parts (the

lowest notes were transposed up by an octave to play it on a standard A clarinet). Today's

professionals use this instrument when performing the concerto, you can watch Sharon Kam on

this YouTube Video . With some professional type clarinets (high end / high price) you can buy

a longer lower part for the instrument and it fits out-of-the-box, otherwise you can have it made

custom-built for your favourite instrument.

The alto-clarinet and the modern form of the bassett horn are looking very similar. They are low

clarinets (in Eb or in F respectively). Today they have the characteristic bend in the barrel which

is usually made from metal - and they usually show a metal funnel like a bass clarinet although

some do not; it seems that is more an esthetical feature. Due to the bends the clarinet can be

built roughly the same hight as a Bb clarinet and it is usually played just held with your hands

(and optionally with a neck strap), while bass clarinets do have a thorn to be placed on the

ground (for holding, a wooden bass clarinet is too heavy).

Alto ClarinetsYou find alto clarinets in harmony bands or symphonic bands, hardly ever in classical symphony

orchestras. And there was only one classical composer who wrote for bassett horn at all; but this

composer was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and the bassett horn was his favorite instrument.

Therefore alone it is very likely that this instrument will stay with us forever.

Bassett HornThe famous clarinet concerto in A was - as far as we know today - originally composed for a

bassett clarinet and not for the A clarinet. That instrument might have looked a little like the

Bassetthorn, maybe without the funnel. Since such instruments don't exist any more, the

musicians use an A clarinet and changed some of the lowest notes to be able to play that parts.

There are original hand-written notes by Mozart and since he precisely knew the instruments and

their tone range we can tell that something like this must have existed.

Today there still are some very old bassett horns in museums (e.g. in Hamburg and Berlin -

seepicture) and they all do have the charakteristic bend and a box-like connecting piece (the

"book") - and with some the bell looks like a french horn. This is probably the reason why it was

named bassett "horn". The crooked form was due to the technical problems building long and still

effective keys. The player had to reach and cover nearly all tone holes with his fingers - in

Mozart's days the modern key was not yet invented.

Bassett ClarinetThe modern Bassett Clarinet is less a Bassett Horn but more an extended version of an A- or B-

flat Soprano clarinet. Today professional clarinet players (like Sharon Kam and Sabine Meyer)

use this type of instrument to play Mozart's famous concerto KV 622 in its original form.

The Bass Clarinet

Low tone - full soundThe bass clarinet is considerably larger than the Bb clarinet - more than a meter (approximately

40 inch) tall, having keys of nearly half a meter (20 inch) in length. The barrel is an S-bent metal

piece, and the bell is bent up and forward like a saxophone's. The instrument is much to heavy to

hold in your hands while you play so you either use the thorn (pointy or with a rubber ball) or a

special carrying construction usually fixed around shoulders and chest.

The first bass clarinets were developed as early as 1800. A wind instrument of that size requires

a perfect key system. Alternatively you can bend the corpus several times so the tone holes get

closer to each other in order to cover them all with your fingers. Not having perfect keys, early

instrument builders chose that way, so that the first bass clarinets did look more like a snake

rather than an ordinary clarinet (see picture).

Francois J. Fetis, a Beligan music scientist, wrote in 1832: "You saw this big, or better huge,

instrument and expected to hear hard, rough tones; nevertheless it was a full, strong and soft

sound. ... " The Italians therefore called the instrument glicibarifono (pronounce: gleetchee

bariphono, meaning "sweet-deep-sounder"), today they call it Clarone.

Yes, looks like a saxophone (it is no coincidence!)1836 the composer Meyerbeer introduced the bass clarinet in his opera "the huguenots" in a

grand recitativo - just at the same time when the famous Adolphe Sax, the inventor of the

saxophone, developed a bass clarinet that was quite similar to today's model (which used the

improved keys). It is since then that everybody (especially Wagner and Verdi) employed the bass

clarinet in compositions for large scale ensembles, the symphonic band music and even in

popular music. Because of its shape the bass clarinet is often confused with a saxophone -

although it is acustically rather a distant relative... nevertheless in the modern form it has got the

same father with Adolphe Sax.

Noted in B flat, violin clefThe bass clarinet notes are written in B flat, usually in the violin clef (rarely in the basso clef), it

just sounds an octave lower than the Bb clarinet. There are no A bass clarinets, nevertheless

some composers require them (exactly when the Soprano clarinet player changes his

instruments from Bb to A, because we go to #-keys). The bass clarinet player has to transpose

then. In contrast to the soprano clarinet's voice, that is possible with bass clarinets, since there

are only few extremely quick movements and "jumps" required. The bass clarinet usually has

calmer movements - comparable to the contrast between violine and violoncello.

4 special bass keys

Awesome tone rangeThe bass clarinet's tone range is wider than any other wind instrument's - it can play as low as a

bassoon (in order to make it possible to play bassoon-voices, the instrument makers use four

additional keys; the professional instruments therefore reach down to deep C - that sounds as B

flat), and as high up as a soprano clarinet.

Widest dynamics of all woodwindsThe bass clarinet's dynamic is even wider than that of a normal soprano clarinet, the Saxophone

is the only other woodwind that has a similar range. Yes, brass plays louder, but then they have

problems with ppp, especially in begginning of a phrase up high. A bass clarinet easily can start

playing a phrase in a nearly unhearable pppp with any tone you like. If you don't know how, try to

carefully muffle the tone by putting the tongue on the lower part of the reed. You can easily play a

crescendo up to the loudest ffff and go back.

Want to be a film star?Listening to film music you find the bass clarinet quite often when the composer wants to

increase the thrill, like when something is slowly approaching...

At the end of the 20th century the bass clarinet experienced a career even in popular music. In

the nineties it was a kind of kult instrument in Europe, but that trend seems over now. In

comparison with the saxophone the variance in sounds you can produce on a clarinet is limited, a

sax is easier and faster to learn, and looks good. Plus saxophones fit well into the electronic pop

music styles of the early 21st century.

Should I buy a cheaper bass clarinet that goes down only to E flat?

Professional instruments today always go down to C (sounds as B flat). But there are bass

clarinets that only reach down to E or E flat. They are a bit shorter, because the lower joint can be

about 25 cm (about 10 inch) shorter, and have 4 keys less. That makes them considerably

cheaper. The manufacturer will tell you that they are of the same excellent quality and that the

four lowest tones will only appear - if at all - in newer pieces, where you can easily replace them

by transposing an octave up. Yeah, sure.

One point in playing the bass clarinet is the sound of the deepest register, and whenever

composers in the last 50 years or so wrote a bass clarinet solo, you can bet it made use of the

wide compass down to the deepest tones. There are not many solo parts in wind orchestras or

symphonies for bass clarinets, and if they are there, you want to be sure you are not limited by

your instrument. So if you can afford it at all, do not buy a short instrument!

The composer wants a deep C - your instrument can't play it - what do you do?So now for one reason or another your bass clarinet only reaches Eb, but the melody goes down

further. That is bad for you; but you have to decide what to do now:

leave it out: If the part is not crucial and the tone is not part of a melody or has to be there because it belongs to an accord - not playing this one note is a possible solution. Especially when bari-sax and tuba play the same note in ff, hardly anybody will notice.

play the one note you haven't got exactly an octave higher - that is OK theoretically and in harmonics, but hardly ever sounds good, and definitely not if it is a part of an important melody.

play the whole melody or phrase - at least a part of it - an octave higher: It is a better solution in the sense of melodical impression, but less satisfying in general sound; especially if you should be the only prominent bass instrument in that part, but you play a tenor voice instead.

if you are good in harmonical theory and have a look at the score, maybe you can replace the missing tone by the quint (five notes above) or a terz (three above). But that only works depending on other harmonical lines around you.

Usually it is wise to talk with the conductor, if there is one.

+ Great sound + less practising necessary than with sopranos- very expensive= An instrument for you?Considering the bass clarinet as your instrument, some points are clear:

The voice hardly ever is technically so demanding that you have to rehearse or practise jumps

and runs for hours like soprano clarinet players have to quite often. Even the second and third

sopranos have to work harder there. But still you have to be technically good; and the long levers

and keys require strong hands and some power. Intonationwise the instrument is less demanding

than the soprano clarinet. With embouchure you can do more when playing the higher clarinets,

because the mouth's volume is smaller compared to the bass clarinet's volume. And: People tend

to hear small deviations better in higher pitches than in lower.

You may find it surprising but you won't need much more breath or lung volume for a bass

clarinet to play the same piece as you need for a soprano. The problem is that the type of voice

that bass clarinets play is not the same as the soprano's: Long and very long legato-lines, often

loud ones with crescendo have to be mastered, and while the soprano is hardly ever alone and

can work as a team (breath intermittently), bass clarinets are often single. In arrangements you

get the cello-part: Beautiful, but then a violoncello doesn't have to breath... ;-)

The bass clarinet is nothing for the primadonna-type: If you really need to play an important solo

part that everybody will hear and remember and you need that in every concert to feel good, then

the bass clarinet will not become your favorite instrument (maybe you should consider switching

to E flat?)

If the orchestra doesn't provide a bass clarinet, that is, if you have to buy your own instrument,

you better not be financially limited. Having to spend less than 5.000 Euro (or US-Dollars) for a

good bass clarinet would be a bargain. You may find used ones, shorter ones (see above) and

instruments from synthetic material (ABS, Resonite) for much less, but even when you buy a

"cheap" bass clarinet for 3.000 Euro you better not be poor. You always should be aware that you

could be having the same fun with a trumpet costing 800 Euro.

Save time and money buying saxophone reedsMany bass clarinet players (including me and my wife) play bass clarinet using sax reeds. There

are people who will call this impossible, but it works well for me. For german bass clarinets you

can use alto sax reeds, for boehm bass clarinets you can use tenor sax reeds. I do it not only

because of the price (about 50%), but it is a question of availability: Good reeds are available for

saxophones in nearly every small music shop at the corner all over the world, while bass clarinet

reeds often have to be ordered in advance. You may as well try an internet mail order business,

but there, too, you can't rely on having them the next day.

What to do with the bass clarinet in the break/pause?

There are always those guys who will disassemble the instrument, sweep through the parts and

put them into the box, after having checked and re-oiled all keys etc. - but many of us don't. In a

concert break you can as well hold the instrument in one hand and your beer or champagne in

the other (looks great as long you have the upper arms of a bodybuilder ;-)

If you have about 70 Euro to spare you can buy an excellent bass clarinet stand (the same stand

as for bassoons, a heavy solid steel thing with a big rubber cup). You can leave the instrument

there, and nobody will kick it over. You really need such a stand if the bass clarinet is one of two

instruments you play in the same concerto, and you don't want to place the expensive instrument

on the floor where somebody may step on it. The floor still is a safer place than putting the

instrument on a chair. So, if you must, turn the mouthpiece of the instrument up (prevents

breaking the reed), and put the bass clarinet onto its opened case on the floor in an open space

where people can see it rather than putting it on a chair (NEVER do that!).

You may as well find an empty corner where you can safely lean the bass clarinet into - but hurry,

bassoonists and bassist and lots of other instrumentalists are looking for the same places!

Beware: Do not try to lean your expensive instrument into a door frame of a door that may be

opened from outside, even if it is locked at the moment!

Extreme depth: Contra ClarinetsThe contra bass clarinet is the largest of all clarinets - about 2,70 meters in length - and not

very common. Usually the composer employs this instrument for special effects. The effects are

not only acoustically, contra clarinets are optically impressive, too. It's extremely deep tone is

comparable to that of a string base. In modern wind band compositions you can find that part

frequently. In the USA and the Netherlands a modern version of the instrument (on the right in the

picture) is often found in bigger school bands and professional ensembles.

Contra alto - and contra bass clarinet by Selmer, classical with wooden corpus, and modern, wound metal contra bass clarinet by Eppelsheimer - all Boehm systems

While contra bass and contra alt voices appear in compositions, the sub-contra-clarinet is rather

experimental, and there are only few examples of it (personally I haven't seen one yet).

Kontra bass and kontra alto clarinetThe contra bass clarinet is noted in B flat, the Contra Alto in E flat. Often - like in US literature -

the Alto instrument is referred to as Contra bass clarinet, too, but you can identify it by the key.

The instruments I played on were traditional German models on which only the lower register was

really good. The higher register is often played by a bass clarinet. These instruments are, of

course, expensive, and they are heavy and difficult to transport. The music shop around the

corner won't have the reeds in stock. Sometimes Bass Saxophone reeds fit - plus they are much

cheaper.

The traditional style instruments (on the left in the picture) look like a bass clarinet, just twice as

big, with a long bent barrel and a large funnel. They are still in use today. They have keys of

nearly half a meter in length. It takes big hands, a big mouth and some lung volume to play them,

but basically the technique is not different from that of a normal clarinet, except that the mouth

piece goes nearly horizontally.

Modern contra bass clarinets, usually Boehm systems, are bent like a bassoon, so that they are

much easier to handle. You can see one on the right in the picture. They do have a small metal

funnel pointing forward/upwards. Most of them instruments are completely made of metal.