Fremont Complex 1998

Transcript of Fremont Complex 1998

Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of World Prehistory.

http://www.jstor.org

The Fremont Complex: A Behavioral Perspective Author(s): David B. Madsen and Steven R. Simms Source: Journal of World Prehistory, Vol. 12, No. 3 (September 1998), pp. 255-336Published by: SpringerStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25801129Accessed: 30-11-2015 18:11 UTC

REFERENCESLinked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/25801129?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of World Prehistory, Vol. 1% No. 3, 1998

The Fremont Complex: A Behavioral Perspective

David B. Madsen13 and Steven R. Sirams2

The Fremont complex is composed of farmers and foragers who occupied the Colorado Plateau and Great Basin region of western North America from about 2100 to 500 years ago. These people included both immigrants and in

digenes who shared some material culture and symbolic attributes, but also varied in ways not captured by definitions of the Fremont as a shared cultural tradition. The complex reflects a mosaic of behaviors including full-time farm ers, full-time foragers, part-time farmer/foragers who seasonally switched modes

of production, farmers who switched to full-time foraging and foragers who switched to full-time farming. Farming defines the Fremont, but only in the sense that it altered the matrix in which both farmers and foragers lived, a matrix which provided a variety of behavioral options to people pursuing an

array of adaptive strategies. The mix of symbiotic and competitive relationships among farmers and between farmers and foragers presents challenges to de tection in the archaeological record. Greater clarity results from use of a be havioral model which recognizes differing contexts of selection favoring one

adaptive strategy over another. The Fremont is a case where the transition

from foraging to farming is followed by a millennium of adaptive diversity and terminates with the abandonment of farming. As such, it serves as a potential comparison to other cases in the world during the early phases of the food producing transition.

KEY WORDS: Great Basin; Colorado Plateau; farmer/foragers; agricultural transitions; behavioral perspective.

Environmental Sciences, Utah Geological Survey, 1594 West North Temple, Salt Lake City, Utah 84114.

department of Sociology, Social Work and Anthropology, Utah State University, Logan,

Utah 84322. 3To whom correspondence should be addressed.

255

0892-7537/98/09(XW)255$15.00/0 O 1998 Plenum Publishing Corporation

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

256 Madsen and Simms

INTRODUCTION

In North America, the area west of the Rocky Mountains and east of

the Sierra Nevada is a landscape of variation and diversity. High alpine meadows, stark salt flats, deep slickrock canyons, broad terminal river

marshes, numerous canyon streams, and dry pinyon/juniper forests are all

found within a few hundred kilometers of one another. Variation is found

even within these environmental categories, with small spring-fed marshes

dotted through the salt flats and willow and cottonwood dominated stream

side vegetation meandering through the pinyon/juniper woodlands. These diverse landscapes are grouped into two primary geographic regions: the

northern Colorado Plateau area along the western slope of the central

Rocky Mountains and the basin and range topography of the Great Basin.

The former consists primarily of a dissected mountain and plateau topog

raphy with elevations ranging from 1500 to 4000 m. Temperatures are

somewhat cooler, in general, than are those to the west in the Great Basin, and the annual average precipitation of lower elevation areas is generally somewhat higher (there are major exceptions). The mountain/valley topog

raphy of the Great Basin engenders what Currey (1991) refers to as a "hemi-arid" environment. That is, the Great Basin is half wet (the moun

tains) and half dry (the valleys), with most of the valley water derived from snow-fed runoff from the mountains. Both the Colorado Plateau and the

Great Basin share the marked seasonality characteristic of all midlatitude zones.

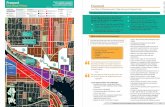

The prehistoric societies of the northern Colorado Plateau and the eastern Great Basin (Fig. 1) are also characterized by variation and diver

sity, much like the landscape in which they were found. They are neither

readily defined nor easily encapsulated within a single description. During the period when farming was part of the human repertoire in the region, 500-2000 years ago, some people were primarily settled farmers, growing maize, beans, and squash in small plots along streams at the base of moun tain ranges. Others were mobile foragers, living primarily on wild flora and fauna. Still others may have shifted settlement locations and group size, adjusting the mix of farming and foraging to changing circumstances. In some areas, the population was relatively dense and social groups showed

signs of incipient stratification. In these locations, people experienced the intensification process associated with farming to the same degree as the

Anasazi and other better-known farming cultures of the Southwest. In other areas, only small, egalitarian, family groups were found widely scattered across the landscape, and were not greatly affected by the feedback loops often associated with agricultural intensification.

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 257

0_300 KILOMETERS

Fig. 1. General location of the maximum extent of the Fremont com

plex in western North America.

When the parameter of time is added to that of geographic space, our

understanding of past behavior in the region can be even more obscured

by common descriptive categories. For instance, during periods as brief as a human lifetime, the lives of some people were relatively constant, while others may have shifted from farming to foraging or various mixtures be tween the two. Consequently, the complexity of social organization was spa tially patchy, with varying degrees of residential cycling among settlements.

The degree to which various groups were linked by consanguinity, by af

finity, or by purely secular association is subject to continued investigation, but variation across space and at several scales of time seems well dem

onstrated, and demographic fluidity was a common characteristic of these

farmer/foragers. If their rock art is a useful guide, these people may have had differing ideological views, as artistic representations vary in funda mental ways across the region. They may even have been linguistically di verse as well, much like the descendants of Southwestern Formative groups, such as the Hopi, Zuni, and eastern Pueblos, who exhibit linguistic diversity at the macro-level of language families.

Currently, these scattered groups of foragers and farmers are called the "Fremont." Despite (or perhaps because of ) the difficulty in catego

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

258 Madsen and Simms

rizing them, the Fremont remain a fascinating topic of archaeological study, since they epitomize both the strengths and the weaknesses involved in

investigating human behavior through prehistoric material remains. They are relatively recent, and many of their sites are so well preserved that we are as likely to know as much about them as about any prehistoric society. These sites are widely distributed and include an array of open structural

sites, temporary camps, and cave/rockshelters. Literally thousands of sites have been documented and mapped and hundreds have been excavated and reported. Yet, unlike the Anasazi and any number of other nearby contemporary prehistoric groups, the Fremont have no known direct de scendants and historical analogy is unavailable to provide interpretive in

sights. While this means that Fremont research does not suffer from "the

tyranny of the ethnographic record" (Wobst, 1978), it also means there are no direct guides to understanding Fremont behavior. Everything we under stand about the Fremont must be inferred from material remains through the application of general theory. The Fremont thus provide an excellent case in which to employ ethnology, ethnoarchaeology, and general theory in both critiquing and refining our construction of a regional prehistory.

The Fremont may be especially pertinent to the food producing tran sition in other cases in the world, such as the Levantine Natufian and early

Neolithic in the Near East (e.g., Henry, 1995), Europe (e.g., Gregg, 1988), and elsewhere in the Americas (e.g., Gebauer and Price, 1992). The dual effects of the adoption of horticulture by foragers and its spread by colo nizing horticulturalists is exemplified by the Fremont. It is increasingly clear that the study of the food producing transition requires understanding the

foraging populations that formed the context of the transition and persisted long after regions were predominantly agricultural in character. Further, the relationships between early horticulturalists and foragers are likely to involve connections which constrain and shape the decisions of both. As

such, the spread of horticulture is much more than the spread of peoples with a farming way of life whose archaeological record dominates that of the typically unidentified foragers of ancient times. The perspective on the Fremont we take here is designed, in part, to facilitate the study of process in the food producing transition and we suggest that the Fremont may be a useful analogy for other cases.

Over the past 15 years there has been a tentative move toward exam

ining the Fremont in terms of behavior: a move we continue here. However, by emphasizing behavior, we do not wish to imply that we think culture is

free-form, infinitely plastic, or ahistorical. On the contrary, behavior is learned and shared, and any understanding of behavior requires an under

standing of evolutionary forces acting upon cultural and genetic variation via selection. As a metaphorical device, we also draw a parallel between

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 259

diversity in the natural ecosystems of the region and the evidence for Fre mont variability. We do not mean to imply, however, that the Fremont are variable because of a simple form of environmental determinism or that cultures in general are uniform or variable depending on gross measures of environmental characteristics. Rather, we suggest that behavioral vari

ability is always present, and when the subtleties of environmental structure are considered, an analysis of variability will be more enlightening than a

search for definitions or boundaries. We draw our perspective on the en

vironment from evolutionary ecology, where environment is "everything ex

ternal to the organism," where the "sources can be physical, biological, or

social," and where there is "an interdependence of decisions' . . . [and] no truly independent variables " (Winterhalder and Smith, 1992, p. 8).

To some extent we dislike using the term "Fremont" because its use

implies that we think there were indeed some coherent prehistoric phe nomena which fit together under such a label, and by writing this summary of the "The Fremont," we unavoidably imply that there was some bounded

entity to which the label applies. We use the term because we recognize the need for labels, and because we are cognizant of the historic back

ground which underlies the term. However, we must stress that we use

"Fremont" as a generic name for an archaeological construct, which, we

suspect, fails miserably in defining a people, who, like the landscapes of the Intermountain West, are not easily described or classified. This does not mean we can escape the need for classification?and this is not a pe destrian call to stop using labels. Instead, we suggest that archaeological classifications need to become attuned to what the evidence tells us about

behavioral variation across space and through time, and from which selec tion produces an evolutionary outcome represented by changing frequen cies of behaviors. In short, we think that Fremont research needs to focus less on categorical definitions and more on the alternative adaptive strate

gies employed by these farmers and foragers. We take this view, because, quite simply, such bounded definitions do

not work. Since the late 19th century, scholars have struggled, unsuccess

fully, to define the Fremont, and because they are not easily categorized and do not readily fit into archaeological classification schemes, they have

been a source of confusion and debate among archaeologists since they were originally identified. The differences between the many small groups of the Great Basin and northern Colorado Plateau areas of western North America were often quite great, and Fremont specialists have had a difficult time defining just who these people were and how they related to each

other. There are, in fact, only three things common to all these people: they grew maize or knew someone who did, they made or traded for pottery and they were not Anasazi (although there remains considerable debate

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

260 Madsen and Simms

about this third common thread). Study has also focused on identifying the Fremont in the context of surrounding regions and has addressed questions framed through metaphors of origin, migration, abandonment, dispersal, and demise. Although all of these questions show concern for the inter

pretation of history as a sequence of bounded events, the effort has been

largely successful, and a general culture history of the Fremont can be told. Our interest in recasting research perspectives on the Fremont is based on

this work and, thus, requires a review of Fremont culture history and a

history of the Fremont concept. Unfortunately, we cannot hope to deal

comprehensively with the mass of information that is currently available for the Fremont in a short review paper such as this, and recommend a

number of recent summaries for more specific detail (e.g., Geib, 1996; Janetski et al, 1997; Metcalf et aly 1993; Spangler, 1995).

The prevailing consensus is that the Fremont developed out of existing groups of hunter-gatherers both on the Colorado Plateau and in the eastern Great Basin (but see Gunnerson, 1969; Madsen and Berry, 1975; Meighan et aLy 1956; Talbot, 1997). Existing adaptive diversity among these groups ensured that decision-making was variable in the face of agriculture arriving from the south. These late Archaic groups were themselves flexible and

adaptable and appear to have ranged from fairly large and relatively sed

entary populations in environments where high return rate resources were

both productive and closely spaced to small, highly mobile family-sized groups where resources were widely dispersed. Over a span of about a thou sand years, from sometime after 2500 years ago to about 1500 B.P., dif ferent groups of these hunter-gatherers adopted, in a piecemeal fashion,

many of the traits associated with the farming societies of the Southwest and Mexico (Fig. 2). However, maize, ceramics, and the bow and arrow were adopted in different spatiotemporal patterns, indicating that these fea tures did not arrive as a complex from the south. Thus, neither diffusion from a single source nor a categorical replacement of existing peoples by migrants can account for a phenomenon far more multifaceted than most

popular notions of the Archaic to Formative transition allow. Current evi dence suggests that the appearance of agriculture in the Southwest stimu lated demographic fluidity, either as a function of the addition of

agriculture to an indigenous foraging base or through the arrival of mi

grants (Berry, 1982; Berry and Berry, 1976; Geib, 1996, pp. 53-77; Janetski, 1993; Spangler, 1995, pp. 426-450; Talbot and Richens, 1996, pp. 196-197).

First, maize and other cultivated plants were added to the foraging subsistence base sometime about 2500 to 2000 years ago in areas on either side of the southern Wasatch Plateau. Outside this region, the hunting and

gathering lifestyles seem to have continued unchanged. In the deserts of the eastern Great Basin domesticates are absent during this early period

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 261

Fremont Radiocarbon Dates (?2 sigma)

?i????f??i???i? Calibrated Age (A.D.)

I 1 i

Fig. 2. "Fremont" radiocarbon dates displayed as a histogram illustrating the florescence and demise of the Fremont complex (adapted from Massimino and Mctcalfe, 1998).

and subsistence was based entirely on wild foods. Second, between about 2000 and 1500 years ago, many of the objects associated with the use of domesticates, such as pottery, large basin-shaped grinding implements, and

bell-shaped storage pits, were added to the tool kit. The production and use of these tools, in addition to the growing of maize/beans/squash, appear to have continued to spread to other hunting and gathering groups to the north and to both the east and the west of the central Wasatch Plateau

region, and by about 1500 B.P. maize and/or pottery are present throughout much of the Fremont region.

Third, between about 1750 and 1250 years ago, architecture at some

(but far from all) open sites changed from small, thin-walled habitation structures and subterranean storage pits to larger semisubterranean timber and mud houses and aboveground mud or rock-walled granaries. The pres ence of such substantial buildings suggests that, at some sites at least, peo

ple were becoming more fully sedentary and were relying more on farming than on collecting wild foods. By about 1200 B.P., foraging groups on the east and west sides of the Wasatch Plateau had adopted and modified many features of settled village life and had differentially integrated these fea tures into their subsistence and settlement strategies. For the next 500 years or so, these patterns defined the Fremont and its core context. Many Fre mont Complex features, however, such as pottery, spread to groups as far

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

262 Madsen and Simms

away as central Nevada, southern Idaho, and northwestern Colorado/south western Wyoming. It seems likely that the spread of these items to these areas was part of the same array of processes common to the Archaic to

Fremont transition?the decisions made by in situ foragers about the adop tion of new items, coupled with the demographic fluidity of local hunter gatherers, conditioned the adaptive circumstances of the indigenous people.

Significantly, there are actually very few things that distinguish even this crystallized Fremont. Pithouse villages and farming are found over

large areas of the United States about this same time and are not very useful in distinguishing the Fremont from other groups. Since pithouses had been used in the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau during the Ar

chaic, they do not necessarily identify either agriculture or "sedentism" but,

rather, indicate greater tethering or redundancy in the structure of mobility. Even within the Fremont area, the form and construction techniques of

both habitation and storage structures are so varied as to preclude useful

classification. Many artifact forms, such as projectile point styles, are also not unique to the Fremont and are not helpful in separating the Fremont from their contemporaries. Indeed, the practice of ascribing a name to

some projectile point styles simply because they are found at a "Fremont"

site does not demonstrate distinctiveness. For example, Bull Creek points from the San Rafael area are morphologically similar to Kayenta points, so labeled because they are found in Anasazi sites to the south. "Uinta"

points, implying some sort of boundary and diffusion from a center in

northeastern Utah, are just as common in northwestern Utah, near the

Great Salt Lake. A number of other material items, such as stone balls, basin-shaped

"Utah-type" metates with small secondary grinding surfaces (Fig. 3), clay figurines (Fig. 4), and elongated corner-notched arrow points, are charac teristic of the Fremont, but they are either so variable from place to place or so limited in distribution that they are not very useful traits for distin guishing the Fremont from other people. Some perishable artifacts, such as one-rod-and-bundle basketry (Fig. 5) and a unique kind of hobnailed moccasin made with the dewclaws from a sheep or deer leg (Fig. 6), may be found at widely separated places within the Fremont area but have been recovered in such limited quantities that it is difficult to determine their distribution in time and space and difficult to analyze variability in the ar tifact style.

In short, it is impossible to categorize the Fremont in terms of material remains because trait lists specific enough to distinguish the "Fremont" from other Southwestern agricultural groups necessarily exclude some of the Fre

mont, while trait lists general enough to include all of the "Fremont" are not specific enough to distinguish the Fremont as a group from other

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 263

Fig. 3. " Utah-type" metate characteristic of some Fremont farming groups. Note the secondary

grinding platform which distinguishes these metates. (Photo courtesy of the Utah Museum of Natural History.)

agriculturalists in western North America. Despite these definitional limita

tions, at the height of the Fremont period, about 1000 years ago, people who in one way or another fit a rather broad description of Fremont could be found from the west slope of the central Rocky Mountains in what is now western Colorado on the east to the middle of the Great Basin in what is now central Nevada on the west. To the north, "Fremont" people ex tended as far as the Snake River plain in what is now Idaho and onto the

plains of western Wyoming. To the south the Fremont variously merged into or abutted the Anasazi areas along the drainages of the Colorado River.

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

264 Madsen and Simms

Fig. 4. Elaborate painted trapezoidal clay figurine characteristic of Fremont groups on the Colorado Plateau. Such figurines strongly resemble rock art figures in some areas. (Drawing courtesy of the Archae

ology Center, Department of Anthropol ogy, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.)

Beginning about 900 years ago, even this generalized "Fremont" began to disappear in a piecemeal fashion. This is most evident on the Colorado

Plateau, where spatial restructuring of horticultural village sites occurred, perhaps influenced by Anasazi aggression from the south. Between 700 and 500 B.P., classic traits such as one-rod-and-bundle basketry, thin-walled

gray pottery, and clay figurines disappear from the Fremont region. By 600

years ago, horticulture, the defining characteristic of the Fremont, seems to have disappeared from the central Fremont area, although it did hang on along the northeastern margins of the Fremont area in northwestern Colorado for an additional century or two. No one can quite agree on what

happened, but there seem to be a number of interrelated factors behind this change. Two things seem most likely. First, climatic conditions favor

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 265

Fig. 5. Schematic of Fremont one-rod-and-bundle basketry (adapted from Adovasio, 1977, p. 68).

able for farming seem to have been changing during this period, forcing local groups to rely more and more on wild food resources and to adopt the increased mobility that generally goes along with their collection. By itself, however, this climatic change probably would not have resulted in the Fremont demise, because the flexibility and adaptability that charac terized the Fremont had allowed them to weather similar changes in times

past. Second, demographic fluidity in the desert West increased, correlating with a millennium of rapid population growth among Southwestern agricul turalists and growth among foragers in California. The 12th and 13th cen

turies in both areas were times of intensification marked by increasing

population. This led to increased investment in farming in the Southwest and increasing social complexity and warfare in California. There was gen

Fig. 6. Construction schematic of a Fremont "hobnail" moccasin. (Adapted from Aikens, 1970,

p. 103.)

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

266 Madsen and Simms

eral demographic upheaval across western North America and this is part of the context leading to the historically known cultural patterns for the

region?the Shoshoni, Ute, and Paiute. The nature of this process is not well understood and has generally

been considered in cultural historical terms which posit "new" groups of

foragers spreading across the Fremont area and hastening Fremont demise.

With the exception of plain ceramics and small side-notched projectile points, by the time of Columbian contact, the "Fremont" are unrecogniz able in the archaeological record. Traditional explanations tend to describe the transition in terms of full-time hunter-gatherers displacing or replacing the part-time Fremont hunter-gatherers with whom they were in competi tion. However, whether or not Fremont peoples were killed off, forced to

move, or integrated into historically known Numic-speaking groups is un

clear, and even the matter of the postulated Ute/Paiute/Shoshoni migration remains a matter of spirited debate (e.g., Madsen and Rhode, 1994). Given the Fremont variability we document below, all of these bounded meta

phors for describing this process can be questioned in terms of real behav ior and further support the idea that it is time for a fundamentally different theoretical perspective to guide study in the region.

In sum, most archaeologists consider the Fremont to have been highly diversified hunters and gatherers living in the eastern Great Basin and west ern Colorado Plateau who, over a period of roughly a thousand years,

gradually adopted and modified some Southwestern farming techniques and associated technology and who, after another 500-600 years of devel

opment, disappeared from the region, being displaced by or being incor

porated into immigrant populations (Fig. 7). Unfortunately, this rather simple scenario does not tell us much about what makes Fremont people "Fremont" or about the variation which characterized them at any one time. More importantly, it does not tell us much about the forces which drive human behavior and does not really explain how and why we have come to know the Fremont in the ways that we have. Much of how we see the Fremont is a product of the way archaeology has been conducted

during the last century, and understanding a little of the history of Fremont

archaeology is a necessary foundation to any interpretation of the Fremont.

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE FREMONT CONCEPT

The Northern Periphery (1890-1955). From the beginning of formal ar

chaeological research, the Fremont have always been defined in terms of the Anasazi. Based on the early antiquarian collecting of Fremont materials

by Don Maguire for the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, Henry Montgomery

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 267

Fig. 7. Major physiographic regions and important sites of the Fremont Complex. (1) Swallow Shelter. (2) Remnant Cave. (3) Hogup Cave. (4) Promontory Caves. (5) Bear River sites; Bear River 1, 2, 3; Levee; Knoll; Willard; Injun Creek; Warren; Great Salt Lake Wetlands sites. (6) Danger Cave. (7) Grantsville, Tooele, and Jordan River Area sites. (8) Utah Lake Area sites, Hinckley Farms, Woodard Mounds, Taylor Mounds. (9) Fish Springs sites. (10) Scribble Rock Shelter. (11) Topaz Slough. (12) Amy's Shelter. (13) Garrison, Baker Village. (14) Swallow. (15) Alta Toquima. (16) O'Malley Shelter. (17) Median Village, Evans Mound, Paragonah. (18) Beaver. (19) Marysvale. (20) Five Finger Ridge, Icicle Bench. (21) Elsinore Burial. (22) Backhoe Village. (23) Kanosh. (24) Pharo Village. (25) Nephi. (26) Ephraim. (27) Nawthis Village, Round Spring. (28) Innocents Ridge, Clyde's Cavern, Pint-Size Shelter. (29) Sudden Shelter, Aspen Shelter, Snake Rock, Poplar Knob, Old Woman, 1-70 sites. (30) Fremont River area sites. (31) Alvey, Triangle Cave. (32) Sunny Beaches. (33) Bull Creek area sites. (34) Cowboy Cave. (35) Windy Ridge, Power Pole Knoll, Crescent Ridge. (36) Cedar Siding Shelter. (37) Nine Mile Canyon area sites, Sky House, Upper Sky House, Four Name House. (38) Felter Hill, Flat Top Butte. (39) Whiterock Village, Caldwell Village, Steinaker Gap. (40) Dinosaur National Monument sites, Boundary Village, Wholeplace,

Wagon Run, Burnt House, Cub Creek sites, Deluge Shelter. (41) Yampa River area sites, Brown's Park, Mantle's Cave. (42) Texas Overlook. (43) Hill Creek area sites, Long Mesa.

(44) Turner-Look. (45) Coombs Cave. (46) Tamarron.

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

268 Madsen and Simms

(1894, p. 234) described the people who produced these pots and projectile points as agriculturalists who were .. part of a large nation in possession of . . . almost all of the Southwestern portion of this Continent." More

formal work by Neil Judd (1917, 1919, 1926) at sites along the eastern margin of the Great Basin served to "establish a cultural kinship between

them and recognized Pueblo ruins elsewhere" (Judd, 1926, p. 1). A. V.

Kidder (1924) used Judd's work to include what was to become known as

the Fremont as part of a Southwest culture area. This definition of a

"Northern Periphery" was reified 3 years later during the first Pecos Con

ference (Kidder, 1927; see also Steward, 1933a) and the Fremont became

firmly fixed as a sort of poor man's Anasazi: people who grew maize, beans, and squash, made pottery, and lived in pit house villages, but who, as the

country bumpkin cousins of the Anasazi, were too backward to live in mul

tistory masonry dwellings. The term "Fremont Culture" was first employed by Noel Morss (1931)

to identify and describe materials recovered by the Claflin-Emerson Expe dition from sites along the Fremont/Muddy River drainage in south-central Utah. While these material remains exhibited some characteristics of the

Anasazi, Morss (1931, p. 77) felt that the "Fremont culture ... is not an

integral part of the main stream of Southwestern development." Further, the "originality shown in many details of their culture makes it difficult to

think of the Fremonters as merely a backward Southwestern tribe . . .

[They were] on the whole, as well fed, clothed, housed and generally com

fortable as their Pueblo II contemporaries" (Morss, 1931, p. 78). Not only were many of the artifact types unique, but the Fremont differed from the

Anasazi in being mobile farmer/foragers with a mixed subsistence base who ". . . moved about, in all probability living on the flats in summer and cul

tivating maize, and in the winter camping in sheltered canyons around the mountains and devoting themselves to hunting" (Morss, 1931, pp. 76-77). Morss felt that the Fremont were distinct not only from the Anasazi to the south, but from the Great Basin horticulturalists identified by Judd and

others, restricting them areally to drainages of the Green River and as far north as the Uinta Basin in northeastern Utah.

Few were willing to concede the distinctiveness pointed out by Morss, and the Northern Periphery concept held sway for more than two decades after the publication of his monograph. This was particularly true in the eastern Great Basin, where horticultural village sites excavated by Steward

(1933a, b), Gillin (1941), and Taylor (1954) continued to be identified sepa rately from the "Fremont" and grouped together loosely under the rubric of "Northern Periphery" and, later, "Puebloid" (Smith, 1941), While the subsistence base associated with the occupation of these open structural sites was thought to have a substantial foraging component, fully mobile,

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 269

full-time contemporary foragers identified at sites like the Promontory and Black Rock Caves were categorized as a completely separate "culture" by Julian Steward and his students at the University of Utah. Unlike Morss, who identified disparate cave and open structural sites as products of mo bile "Fremont" farmer/foragers, Steward separated them into a mobile,

hunting and gathering, Athabaskan speaking, "Promontory Culture" (Stew ard, 1937) and a sedentary, farming, "Northern Periphery" (Steward, 1933a, b) culture, which apparently coexisted for at least several centuries.

This notion of separate Great Basin farming and foraging "cultures" was challenged by Jack Rudy. Based on extensive survey work and some limited test excavations of cave sites, Rudy held that the "Puebloids" (he felt the phrase "Northern Periphery" was denigrating) "were gathering hunting peoples relying only secondarily upon horticulture

" (Rudy, 1953,

p. 169). Like Morss* "Fremont," the "Puebloids were a semisedentary peo

ple who built houses and practiced limited horticulture, [but whose] de pendence ... on gathering and hunting to supplement their diet is attested

by the large number of camp sites where numerous points and flaked stone

artifacts as well as Puebloid pottery are found" (Rudy, 1953, p. 4). In many respects, the interpretations of Rudy and his contemporaries exemplify the blind men and the elephant nature of Fremont research which has char acterized interpretation of the Fremont Complex from the very beginning, and which continues to the present (Janetski and Talbot, 1997a, p. 3). That

is, those whose interpretations are associated with their work at temporary camp sites tend to see the Fremont as mobile foragers, while those whose research is focused on horticultural village sites tend to see them as sed

entary farmers. To the east, in the "Fremont" area proper, where many horticultural

village sites were excavated after the 1930s (e.g., Gillin, 1938; but see Burgh and Scoggin, 1948), the latter view was strengthened in the last and most comprehensive summary of the "Northern Periphery" (Wormington, 1955). No longer were the Fremont the mobile farmer/foragers of Morss, but rather the "Fremont people were agriculturalists and grew corn, beans, and

squash" (Wormington, 1955, p. 173). While they "depended on hunting to a greater extent than is usual for agriculturists," and "there was an unusu

ally large dependence on wild plant products," the Fremont lived in per manent houses associated with numerous storage structures and appeared to be essentially sedentary farmers. In all but a few material culture dif

ferences, they were very much like the Puebloid people to the west and,

together with them, could be categorized, in Wormington's view, as a more

unified and tightly defined "Northern Periphery." This first step toward a unified concept of the Fremont was quickly

followed in 1956 by publication of the results of a symposia series sponsored

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

270 Madsen and Simms

by the Society for American Archaeology. Members of the Southwest sym posium jointly recommended that the many similarities of the Puebloid and Fremont cultures be recognized by a change in nomenclature. Henceforth, horticulturalists in both the Great Basin and the northern Colorado Plateau would jointly be recognized as "Fremont," with a basic difference between

groups in the two geographical provinces recognized by the addition of a modifier separately identifying people in the west as "Sevier Fremont"

(Jennings, 1956). Fremont Variants (1956-1980). Now that the "Fremont" were no longer

peripheral to other Southwestern peoples and had been recognized as a

distinctive, albeit poorly defined, cultural entity, Fremont researchers saw

their job to be primarily twofold: to classify the Fremont into hierarchical cultural categories identified by discrete traits and to figure out where they came from and what happened to them. For the most part, the majority of archaeologists agreed that at least the initial aspect of the latter question had been largely answered. The Fremont were thought to be essentially a

product of in situ Archaic hunter/gatherers adopting maize/beans/squash horticulture from the Southwest, together with many of the tools associated with the use of domesticates. Suggestions that the Fremont were actually Anasazi people who moved north (e.g., Gillin, 1938; Gunnerson, 1960;

Meighan et al.9 1956) were largely ignored. That apparent unanimity rapidly changed in the 1960s when attempts

were made to reconcile the enigmatic "Promontory Culture" of Steward

(1937) with the rest of the Fremont. Gunnerson (1960) initiated the discord by following up Steward's correlation of the Promontory Culture and Athabaskan speakers with a detailed trait list correlation between artifacts of the protohistoric Dismal River Apache and those found by Steward and others in the caves around the Great Salt Lake. Aikens (1966) took excep tion to this reconstruction, but only its chronological aspects, suggesting that the Promontory Culture was but a "variant" of the Fremont and that the intrusion of Plains Athapaskans took place much earlier than Gunner

son, and even Steward, thought. Since the Fremont as a whole were now a coherent cultural entity, that meant that all the "proto-Fremont people were bison hunters of Northwestern Plains origin, probably Athapascans. They expanded westward and southward into Utah at approximately A.D. 500 [and] synthesized, from Plains and Anasazi elements, a mixed hunt

ing-horticultural economy. . . . After approximately A.D. 1400-1600, [they] drifted eastward [and] merged with Plains culture to develop the culture

represented by the Dismal River aspect . . ." (Aikens, 1966, p. 10). In one fell swoop Aikens (1966) thus solved the questions of both

where the Fremont came from and what happened to them. Unfortunately, few Plains specialists and even fewer Fremont practitioners agreed with

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 271

him, and the prevailing opinion on Fremont origins continued to be one of Southwestern horticultural traits added to an Archaic hunter-gatherer base. As for the "ultimate fate" of the Fremont, opinions continued to be

mixed, with some suggesting that the Fremont withdrew to the south to

become the Hopi (Wormington, 1955), others that they reverted to a fully mobile foraging lifestyle and were eventually absorbed by Numic-speaking populations (e.g., Jennings, 1960; Rudy, 1953), while still others believed that the Fremont actually were the original Numic-speaking peoples and

spread out to occupy historically known areas (e.g., Gunnerson, 1969). As a result, Aikens' basic thesis, while stimulating, was rather short-lived. It

did, however, have a major by-product in that many began to heed Aikens'

(1966, p. 88) suggestion that "the internal characteristics of the Fremont culture require further study. Areal divergences within the Fremont culture in Utah have been recognized, and require more thorough explication. The

exploitive cycle or schedule of Fremont horticulturists-hunters is yet unknown."

This call for the study of Fremont variants was almost immediately answered by Ambler (1966b) and Marwitt (1970). Based on a surge of new

descriptive studies, primarily of open village sites (e.g., Aikens, 1967; Am

bler, 1966a; Breternitz, 1970; Fry and Dalley, 1979; Leach, 1966; Marwitt, 1968; Sharrock, 1966; Sharrock and Marwitt, 1967; Shields, 1967, n.d.; Shields and Dalley, 1978; Taylor, 1954, 1957), Ambler and Marwitt both expanded the number of Fremont "subcultures" (e.g., Aikens, 1966) from two to five (Fig. 8). Although the definitions of these "variants" differed only in detail, Marwitt's treatment received the most play, despite being

largely derivative, since his dissertation was published in a widely distrib uted monograph series, while Ambler's dissertation had only limited dis tribution. As a result, the names applied by Marwitt have largely been followed.

Three of the five variants, the Parowan, the Sevier, and the Great Salt

Lake (from south to north), were in the Great Basin, and two, the San

Rafael and the Uinta (also from south to north), were on the Colorado Plateau. Both Ambler and Marwitt defined the "Fremont as a single cul

tural tradition with a number of regional variants ... [and] the entire area

representing the extent of Fremont culture is considered here an areal tra

dition . . . taxonomically equivalent to Anasazi" (Marwitt, 1970, p. 136;

original italics). In a number of instances, Marwitt was also able to define

temporal differences as well as spatial differences, and he identified se

quent phases for the Parowan, Great Salt Lake, and Uinta Fremont based on a wide array of newly available radiocarbon dates. The regional variants were defined on the basis of "congeries of traits," although "the defining traits are not all evenly distributed within a particular region and trait

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

272 Madsen and Simms

Fig. 8. Fremont "variants" as defined by Richard Ambler (1966b).

gradients or transitional zones are apparent between regions" (Marwitt, 1970, p. 138). As a result, Marwitt (1970, p. 138) considered the regional boundaries to be only "gross approximation of possible cultural boundaries

subject to modification," as additional data allowed the boundaries to be more tightly defined.

The definition of these regional variants received almost immediate

acceptance, with the call for better definition of their "boundaries" direct

ing much of Fremont research for the next decade. Initially, refinements of these regional variants continued to be made through more comprehen sive lists of material traits, but this trait list approach ran into trouble al most immediately. Ambler (1970, p. 2), for example, in trying to define "Just What is Fremont," was "rather surprised [to find that] one of the

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 273

principal difficulties in the use of trait lists to define the Fremont is the problem that there are actually rather few distinctive and typical traits that are found over the entire area usually considered to be Fremont." Marwitt's

variants, despite the claim that they were based on "congeries" of traits, were defined primarily on the basis of pottery differences (e.g., Madsen, 1970; R. Madsen, 1977), and other kinds of artifact categories, such as pro jectile points and house types, soon proved to have markedly different kinds of distributions. However, Marwitt (1970, p. 138) also suggested that his regional variants had "more-or-less distinct ecological correlates . . . [al though] ... a defensible ecological definition of each variant is not possible at present." In keeping with larger trends in American archaeology, this

helped shift research toward Fremont cultural ecology. The focus of the cultural ecology studies which followed Marwitt's

summary was on "adaptation" and on the environmental settings where Fremont sites were found rather than on material traits, but these ecologi cally based definitions of Fremont variants ultimately suffered from the same basic problem as did the earlier artifact based definitions. The same

diversity which plagued trait list definitions of the Fremont made these

environmentally defined variants equally fuzzy because environmental traits were merely added to material traits in the definition of prehistoric "cul tures." For example, Madsen and Lindsay (1977; see also Madsen, 1979) questioned the five-variant classification scheme of Marwitt and Ambler based principally on differences and similarities in environmental settings and land-use patterns. They suggested instead a reversion to the larger categories of the Basin Sevier and Plateau Fremont, with the possible ad dition of a yet-to-be-named Plains-derived "culture." However, because of internal variability within each area, these proved to be just as unwieldy as the "cultures" derived through artifact trait lists, and they were ulti

mately no more useful and no more widely accepted. A more fruitful aspect of these cultural ecology approaches to under

standing the Fremont was a more intense focus on subsistence and settle ment patterns than was the case in earlier Fremont studies. Berry (1972, pp. 158-164), using a "systems" approach, created a subsistence model for the Parowan Fremont which identified horticulture as the defining charac teristic of settled Fremont village life in that area. Dynamism was introduced when Berry modeled three "system states" correlating changes in maize pro duction with the exploitation of wild foods. He argued that "none of the wild species exploited by the aboriginal populations was productive enough to allow sedentism in lieu of adequate crop yields" (Berry, 1974, p. 70; also

1972, pp. 163-164), and during periods of decreased maize production, peo

ple would disperse from the farming sites and become hunter-gatherers. "Two distinct adaptive strategies (agricultural and hunter-gatherer) were, in

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

274 Madsen and Simms

part, contemporaneously practiced within the areas encompassed by the Parowan variant. The hunter-gatherer population aggregates were probably derived from households that had formerly practiced agriculture" (Berry, 1972, p. 169).

Madsen and Lindsay (1977) raised the possibility that settled Fremont village life along the western margin of the Wasatch Plateau was due, at

least in part, to a reliance on the collection of wild plants, particularly marsh resources, supplemented by maize agriculture. They based this hy pothesis on the distribution of village sites in or near marsh ecosystems and on pollen from the floors of many structures at the central Utah site of Backhoe Village, which suggested that an array of wild plant types, par

ticularly cattails, were heavily utilized. The seeming contrast between Berry

(sedentary by virtue of maize) and Madsen and Lindsay (sedentary in places because of concentrated wild food supplies) opened up the issue of Fre mont variability in behavior. Berry glimpsed the problem when he wrote, "Fremont specialists have primarily concerned themselves with minor re

alignments of his [Marwitt's] culture-variant 'boundaries/ leaving the broader concept of Fremont as a "unique" entity unchallenged" (Berry and

Berry, 1976, p. 37). Berry advocated a rereading of J. O. Brew's (1946) "The Use and Abuse of Taxonomy," a suggestion that in retrospect seems even more relevant 20 years later.

It was becoming clear that Fremont specialists were beginning to spin their wheels, and the results of a 1978 Fremont symposium intended to

produce some consensus were modest at best (Madsen, 1980). While eve

ryone agreed that there was some phenomenon that could be labeled "Fre

mont," few could agree on what it was. Some felt that the Fremont was a

"Culture" and that "any population which constructs Fremont basketry is Fremont" (Adovasio, 1980, p. 40; original italics), but most felt more com fortable thinking of the Fremont as, at best, a culture area encompassing a variety of groups operating in a variety of ways.

Behavior and Fremont Farmer/Foragers (1980-1998). By 1980 it was clear that the long struggle to define what amounts to ethnic and or linguistic identities among Formative complexes north of the Anasazi had ended in failure. While the Fremont were distinctive enough to preclude explanation as a result of mass migration from outside their known area, there was so much internal variation that it was impossible to define bounded cultural entities using any criteria, from tools to food sources to site types. The re action to this failure was varied, and for a while Fremont research seemed at loose ends. Some viewed this failure as a product of the limited material record and contended that archaeologists could never (or rarely) address the kinds of ethnicity questions that had structured Fremont research in the

past (e.g., Adovasio, 1980). Some tried, but the difficulty of bridging the

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 275

cultural ecology common to American archaeology at the time and the trait lists of Fremont culture history is apparent in an ill-fated attempt to develop "a composite model" (Anderson, 1983). There was an emerging sense that the very concept of "Culture" was at the heart of the problem. This view

was some time in developing, but it had its roots in the growing consensus

(e.g., Hogan and Sebastian, 1980; Holmer, 1980; Madsen, 1979) that the problem with the definition of Fremont "subcultures" was more a product of theoretical orientation than it was of poor or confusing data.

By 1982 this view began to crystallize. First, there was the recognition that the Fremont were composed not merely of farmers who did a lot of

foraging for wild foods, but distinct groups of farmers and hunter-gatherers. In summarizing the Fremont of the eastern Great Basin, Madsen (1982a, p. 218) pointed out that "despite the relative uniformity in tools and other artifact types, subsistence and settlement modes ranged from sedentary groups dependent on both domesticated and locally procured wild re

sources, to sedentary groups dependent primarily on local wild resources, to nomadic groups dependent on resources from a variety of ecological zones," and recognized that "the presence of nomadic collectors/harvesters who made the same tools (including pottery) and either grew or traded for corn does not Tit' well with the classic definitions of Formative Stage cultures. . . ."

Second, there was a shift toward an elucidation of "behavior" as an

alternative to the preoccupation with definitions, categories, and bounda ries based on a narrow model of culture comprised of shared traditions

and, by implication, identity, and even language. Madsen (1982b) found it difficult to classify a site along the southern margin of the Fremont/Anasazi

interface, speculating that people there could as well be called "Freazi" or

"Anamont" and bemoaning a cultural/historical approach which required such labels. O'Connell et al (1982) called for a shift away from both culture history and cultural ecology and toward theoretically based attempts to "re construct behavior." They proposed "... that one cannot successfully in

terpret and explain past behavior patterns except in terms of some

consistent theoretical perspective that identifies the principles underlying these patterns and provides the basis for predicting the forms they might take under various circumstances" (O'Connell et al9 1982, p. 236). Based on work at seasonally occupied sites in the Sevier Desert, Simms (1986), like others before him, directed attention to the patterns from small sites but attempted to operationalize the behavioral goal using the concept of

adaptive diversity. This referred to behavioral plasticity during the life his tory of individuals, a plasticity which may be accompanied by residential

cycling between settled and nomadic populations. Similarly, in a summary of the Fremont designed around this same behavioral perspective, Madsen

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

276 Madsen and Simms

(1989, pp. 27-28) emphasized that Fremont variability does not consist of people with different types of shared behavior, but rather that "a single individual may well have lived the entire range of variation, from full-time farmer in a settled village to full-time mobile hunter-gatherer, in the space of a few years." All of these are views which exemplify the dynamism and unboundedness of a behavioral perspective.

By the end of the decade, the abandonment of "culture" as an organ

izing concept and a focus on "behavior" as a research strategy had infiltrated much of Fremont archaeology, probably because the old goal of creating more classifications, while offering the pretense of originality, failed to lead to any new understanding. We have strongly advocated this point of view. In 1989/1990 we pointed out that "it is our concept of culture which is at the heart of our problem in defining the Fremont. [We have] tended to see

culture as something tangible; something having boundaries and limits and

which can be placed in categories. [But culture is] more elastic, a kind of unbounded social environment in which individuals find themselves. [As a

result,] ... we cannot always expect to define clearly recognizable sets of

traits that identify prehistoric 'cultures,' and that the problems Fremont ar

chaeologists have had over the last half-century in trying to define the limits of Fremont culture and its variants, may not be due to poor excavation tech

niques or insufficient amounts of data, but to the fact that such limits do not exist" (Madsen, 1989, pp. 23-24). Rather than view the Fremont as a

"culture," it was suggested that we use ". . . the term 'Fremont' as an um

brella which includes a diversity of human behavior" (Madsen, 1989, p. 67). Nearly 60 years after Morss (1931) had first defined the Fremont, it was clear that the "... historical preoccupation with defining the Fremont has

outgrown its usefulness. The concept is a stereotype, routinely confusing the variables of material culture, techno-economic patterns, language, and eth

nicity, [and] . . . presents a naive and reductionistic scenario of prehistoric cultures. [The Fremont should] be examined from a behavioral rather than a cultural perspective" (Simms, 1990, p. 1).

The recognition that we can do more with the Fremont is now wide

spread, and most current workers seem to use the term as an umbrella

covering an array of behaviors. There remains, however, a tendency to see

variability itself as just a fancy way to classify the Fremont along a one dimensional forager-farmer continuum, a tendency which fails to come to

grips with the implications of adaptive diversity and a less bounded concept of culture. The utility of recent proposals for yet additional categories in the absence of theoretically informed questions awaits demonstration [e.g., the "Tavaputs Phase" (Spangler, 1995) or the "Gateway Tradition" (Home et aL, 1994)]. Nor has the concern with finding a unitary definition of the Fremont expired. One recent Alexandrian solution used in classifying the

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 277

diversity of behaviors encompassed by the term "Fremont" is simply to limit that diversity by definition (Talbot and Richens, 1996, pp. 13-14, 197). In this view, only farmers are Fremont, and foragers are perforce not Fremont even though they may make "Fremont" basketry (contra Adovasio, 1980) or pottery. By definition, this implies that people must have sometimes

been Fremont and sometimes not in instances where they lived an agricul tural lifeway while they were young, but in middle age no longer did (contra

Madsen, 1989; Simms, 1986,1999). This view denies study of the life history of individuals by substituting the term "adaptive strategy" for the old terms "culture" and "peoples."

The dominant current view is that the Fremont can be anything we

want the Fremont to be, and in several recent treatises, distinctions among researchers and research interests have been drawn as a way to accommo

date eclecticism. Some researchers are "stretching outward in search of

variability, while others cling to evidence of cohesion within the Fremont world" (Wilde and Talbot, 1996, p. 14), some search for "patterns," and still others ask what "causes variations" (see Janetski and Talbot, 1997a,

p. 9). This apparent eclectisism is deceiving in that it masks a theoretical void which currently seems to plague Fremont research. The Fremont can

be all things to all people only because we have devised no way to come to grips with the many ways in which farmers and foragers were operating in the region and with how they were interacting with one another. While

we subscribe to an interest in what causes patterning and hold that because

patterning amounts to varying mixes of alternative behaviors selected from extant variation, it is impossible to study pattern without knowing variabil

ity. A coherent model of Fremont foragers and Fremont farmers remains to be drawn, but it will have to avoid the delusion that we can understand

what went on in prehistory by definitional proclamation.

A BEHAVIORAL MODEL OF MIXED FARMERS AND FORAGERS

To provide a context organizing the variation and patterning that com

prises the Fremont complex, we outline here a behavioral model that de

scribes the circumstances encountered by people during the Fremont

period. At the same time, we seek to build upon previous Fremont culture

history by avoiding another description cast in terms of cultures and their

boundaries, with accompanying descriptions of "interactions" among these

conceptually closed entities. Our goal is a model reflecting the dynamics of life. Such a model must incorporate change in the frequencies of alter native behaviors over time and recognize that behavioral variation is ex

pressed within cultural systems (resulting from competition and conflicts

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

278 Madsen and Simms

of interest), not just between them. It must also incorporate the fact that

identity, ideological belief, and language exhibit plasticity as well as per sistence and that, while they are part of the environment that shapes decision-making, they are an evolutionary result of "the tyranny of circum stance" (Blurton-Jones, 1991, p. 95).

Aspects of the Fremont archaeological record that may be organized by such a model include the time- and space-transgressive nature of the

spread of traits, the variation in adaptive strategies, the fragmentary nature

of the Fremont "demise," and the degree of synchrony in process between the Fremont and patterns elsewhere, most notably the American Southwest and the Great Basin. Like all theoretical statements, this model is com

posed of categories. They are devised, however, to recognize that while there is unity in the Fremont pattern in some respects, there is also a de

gree of variation that makes it impossible to define the Fremont in any but the most trivial and indefensible manner. By modeling the circum stances in which people of the Fremont period interacted, we can move on to a more human understanding of the prehistoric record, model the reasons for the diversity, and better address issues of social boundary for

mation, maintenance, and change, We are interested in a model of behavior that recognizes the dynamism found across cultures in the historically known world, a dynamism that is often denied in idealized archaeological reconstructions.

The historical foundation for describing the behavioral circumstances of the Fremont period centers around the appearance of agriculture in a

region occupied by Late Archaic foragers. These foragers had a long history in the area and exhibited diversity in adaptive strategies. Some were teth ered to productive, but variable wetland habitats, which conditioned the

tempo of mobility and the intensity of use of surrounding areas. Others were foragers of the deserts and mountains moving among patches but po tentially tethered at times to productive areas or caches of stored foods.

The Late Archaic was a mosaic of adaptive strategies that ranged along a

continuum from the settled to the nomadic, but a continuum also exhibiting a temporal dimension in the expression of mobility (Kelly, 1995, 1997; Upham, 1994). This diversity is unified under the term Late Archaic by a material culture that extends widely across western North America. The

degree of Late Archaic ethnic and linguistic variability across the area that would later be called Fremont is unknown, but the general trend through time is toward greater differentiation with increasing population (Madsen, 1999). However, there may also have been broad connections of language and other integrative features across the Late Archaic of the Colorado Pla teau and the Great Basin. At the Archaic-Fremont transition, some in

digenous populations adopted agriculture by incorporating cultigens into

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 279

their adaptive strategy, probably in places where mobility was either teth ered or spatially redundant. Other people found that an agricultural option was not in their immediate favor and rejected it. Still others with a farming way of life may have migrated into the region, colonizing unoccupied areas, areas occupied by low density foragers, or areas of indigenous foragers who were beginning to practice farming. The implications of this historical foun dation for constructing a model are several.

First, the farming transition is not simply a matter of farmers encoun

tering foragers, regardless of whether the farmers are indigenous converts or immigrating colonists. Diversity in Late Archaic adaptive strategies must be taken into account if we are to understand the spread of agriculture into the Fremont area. This issue has been obscured by the tendency to see horticultural sedentism and nomadic foraging as polar types, discount

ing the evidence that the Archaic of western North America had long ex

hibited instances of decreased mobility in the absence of agriculture. Second, the circumstances faced by indigenous peoples changed, re

gardless of whether they adopted farming or not. This point should also hold for interactions among foragers at and perhaps beyond the fringe of the agricultural spread, since the impact of the agricultural transition ex

tends beyond the area where it can be recognized through the presence of

farming societies. Thus, a continuation of foraging during Fremont times is not simply a continuation of the Late Archaic. For the foragers of the Fremont period, the Late Archaic no longer existed. This issue has been obscured by the bounded nature of cultural-historical discourse, where the

workings of prehistory are sacrificed for the convenience of evolutionary stage terminology (e.g., Archaic/Formative, Mesolithic/Neolithic), a habit that diverts attention from evolutionary processes such as selection from

among alternative forms.

Third, the circumstances of farmers must include the impact of fora

gers in an area because the matter of influence is far from being a one

way street. This dynamic has been obscured by the tendency to describe

the prehistory of regions in terms of the most archaeologically visible pat terns, in this case, that of farmers. A similar problem in the nearby Ameri can Southwest has led to conceptual shifts significant to the Fremont case.

Plog (1984) refers to the archaeological record of farmers as "strong" pat terns, contrasting with the "weak" patterns of foragers. Upham (1988,1994) contends that there are "two archaeologies" in western North America, one associated with foragers of the Archaic period, followed by farmers "that are generally referred to as Formative, despite the fact that both gath erer/hunters and agriculturalists were common features of the landscape"

(Upham, 1994, pp. 119-120).

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

280 Madsen and Simms

Finally, the Fremont period is over 1200 years long, and while change has always been recognized, the model we promote here casts this change, in terms of cultural variability organized not as variants, phases, or any number of other kinds of subdivisions, but as changing contexts of selection. The concept of selection focuses on the processes by which patterns we

recognize as archaeological cultures are produced from behavioral variabil

ity. This is an advantage over those who see patterning and variability as

mutually exclusive categories, since within the context of selection they are

merely aspects of the same evolutionary process. The historical bases for modeling Fremont behavior combine in vari

ous ways. They weave through a four-part model of the contexts of selection we term here behavioral options, matrix modification, symbiosis, and

switching strategies. As in all archaeology, the success or failure of theo retical models in adding new insights hinges on the ability to recognize past behavior in the archaeological record. We do not, however, propose a specific archaeological manifestation for each context of selection. Each context of selection is a form or subset of the others, and they are not

mutually exclusive. The exceptions may be symbiosis and switching strate

gies, which may or may not occur in association. We thus organize our

discussion of archaeological manifestations by context of selection, not with the intent of separating matrix modification from behavioral options, but to show how each context of selection illustrates aspects of the Fremont

archaeological record. Our intent is to redirect which questions are asked and how data are used, not redefine the Fremont.

Behavioral Options. This context of selection points to an ever-present dynamic, a dynamic that plays out not simply between cultures, but between

groups of people with competing interests. The transition from the Late Archaic to the Fremont changed the behavioral options available to people by increasing both the number and the kinds of technological and social

concepts from which they were able to learn and select. There is more to this transition, however, than a unidirectional diffusion of cultigens and/or the migration of people leading to the Fremont. Due to the variable nature of the underlying foraging base, the concept of behavioral options cannot be applied in monolithic terms. Rather, behavioral options vary with par ticular situations, a point which should apply to any region of the world at the dawn of the food producing transition.

The situational nature of farming and foraging options is particularly critical in understanding the Fremont complex. Barlow (1998, pp. 160-161) provides an in-depth analysis of the economic efficiency of farming and for

aging among the Fremont and concludes that "... corn farming with simple technology is economically comparable to collecting and processing a variety of eminently storable seeds and nuts." She estimates that the caloric return

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 281

rates for farming maize are of the order of 300 to 1800 kcal/hr, return rates that are well within the range of many wild plant resources and substantially less than most faunal resources. Collecting a number of wild plant resources, such as cattail pollen and rhizomes, bulrush seeds, and pinyon nuts produces return rates higher than does farming maize, and ". . . the abundance [of these] resources should structure spatial and temporal variation in time in vested in farming activities" (Barlow, 1998, p. 194). That is, economic for

aging models suggest that farming should be found only where the resource

base is depressed to the point where lower-ranked seeds such as shadscale and wild rye begin to appear in the diet. In situations where high-ranked resources are abundant, farming is unlikely to occur. Farming among fora

gers, then, is a behavioral option that allows them to mediate variations in the resources base on the lower end of the efficiency scale.

Changing behavioral options can be tracked in the traditional archae

ological manner with the spatiotemporal appearance of traits such as maize, the bow and arrow, and ceramics. These data indicate the direction of in troduction and identify where gaps in the presence of the trait occur. For

example, maize, the bow and arrow, and ceramics were adopted succes

sively across the Fremont region. While maize clearly arrives from the south via Basketmaker and the later Anasazi populations, the bow and arrow

appears as part of a broad regional adoption of this technology across the Great Basin during the Late Archaic and early Fremont periods (Aikens, 1976). Initial use of the bow and arrow by some Fremont occurs when Basketmaker populations in the Southwest were still using the atlatl and

dart, despite the adoption of maize from these Southwestern populations. On the other hand, maize made up a significant portion of the diet at

Steinaker Gap in northeastern Utah by 1800 B.P. (Coltrain, 1996, p. 119), in association with atlatl and dart technology (Talbot and Richens, 1996, pp. 81-86). This illustrates the multi-directionality of trait introduction and the patchiness that is possible in the spatial distribution of traits. Ceramics are adopted by the Fremont from the Southwest four to five centuries after

maize, probably in response to changing Fremont mobility. These kinds of

patterns suggest that there is something to be gained by envisioning the Archaic to Fremont transition as less about contact between different peo

ples and more a function of local decision making by groups presented with new options.

Tracing the movement of traits in the context of increasing behavioral

options should also help distinguish the adoption of farming by indigenous

peoples versus colonization by immigrant farmers. Some caution is war

ranted here, however, because the appearance of both indigenous farming and farming brought by immigrants may occur in a patchy fashion. A classic

and oft-cited example is the differential movement of 40 material culture

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

282 Madsen and Simms

traits across tribal boundaries in east Africa documented by Hodder (1977). That case is a useful reminder that inference about ethnic and linguistic boundaries dependent on one or two traits may be correct or incorrect

depending on the traits chosen, but there is no consistent way to choose

the right traits from the wrong ones. We consider the problems with dif ferentiating colonists from indigenes as part of other contexts of selection that arise from changing behavioral options.

The notion of changing behavioral options can be applied at various times during the Fremont period and holds the potential to explain pat terning in artistic styles, the appearance of ceramics among foragers in east ern Nevada, and perhaps the influx of populations associated with the Numic Spread. The concept of behavioral options is also useful in under

standing geographic regions outside the area of immediate interest and how

change can be synchronous with events in other areas. This is reminiscent of Berry's (1982) model of synchrony between Anasazi demographics of the Colorado Plateau and the southern Basin and Range regions. While these patterns were interpreted in terms of migration versus diffusion and

we do not wish to revive the notion of repeated, wholesale population movement, the attempt to direct attention to the larger picture and a more

dynamic pre-Columbian America is significant. Demographic change out

side of the Fremont area proper undoubtedly altered the behavioral options available to Fremont foragers and farmers, and the northward movement of Basketmaker-period groups in the Colorado Plateau portion of the Fre mont region may have been shaped in part by demographic change in the Southwest. Perhaps more important, however, are the relationships be tween regions expressing the strong archaeological patterns of farmers and the weak patterns of foragers. Rather than advocate a return to the days

when the hinterlands around centers of complexity such as Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, or Mesa Verde, Colorado, were mere epiphenomena of

change at the centers, we suggest that the relationships may be more subtle than mass migration or an expectation of routine movement of "tradeware"

ceramics, since neither characterizes the boundary between the Anasazi and the Fremont. The relationships may, nevertheless, be significant when viewed in demographic terms and as spheres of influence. This perspective has been useful in understanding the seeming hodgepodge typical of the weak archaeological patterns surrounding Chaco Canyon, such as the Zuni, Acoma, and Albuquerque areas, in light of the dynamics of Chaco, without

attributing boundaries to the vague and behaviorally unrealistic concept of shared cultural traditions (Tainter and Plog, 1994). We suggest that a broader picture framed in terms of spheres of influence and strong versus weak patterns may help organize the hodgepodge of the variable patterning characteristic of the Fremont region.

This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:11:26 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Fremont Complex 283

Matrix Modification. The presence of farmers alters both the physical and the social environment of indigenous foragers and, thus, represents a

specific expression of behavioral options. As a subset of changing behav ioral options, matrix modification emphasizes the impact the appearance of farming has on the settings in which both foragers and farmers lived, and on how change in these selective contexts affected the decisions people made. In other words, the concept of matrix modification focuses on the circumstances that shape behavior, rather than on trying to define the Fre mont by tracing the spread of styles and artifacts. For example, the de

pression of the local foraging resource base and constraints on the movement of foragers created by the presence of sedentary farmers alter the behavior of indigenous foragers regardless of whether or not they en counter new technological and social concepts.

A hallmark of Fremont development was the appearance of local

population centers such as the Parowan Valley, the Sevier Valley, the Wasatch Front, and perhaps the east Tavaputs Plateau, to name a few. The chronology of relatively large Fremont sites is consistent with the proposition that farming promoted a dynamic mosaic of intensified human presence. Occupations at most of these large sites were accretional and/or

episodic. Talbot and Wilde (1989) attempted to document variations over

time and space in the intensity of Fremont occupations using compilations of radiocarbon dates. Massimino and Metcalfe (1998), on the other hand,