FORUM ARTICLE The Haiphong Shipping Boycotts of : Business ...€¦ · FORUM ARTICLE The Haiphong...

Transcript of FORUM ARTICLE The Haiphong Shipping Boycotts of : Business ...€¦ · FORUM ARTICLE The Haiphong...

FORUM ARTICLE

The Haiphong Shipping Boycotts of and

–: Business interactions in the

Haiphong-Hong Kong rice shipping trade

BERT BECKER

Department of History, The University of Hong Kong

Email: [email protected]

Abstract

The main focus of this article is the Haiphong shipping boycotts of and –,which were conflicts over freight rates on rice which arose between several Chineserice hongs in Haiphong (Hai Phòng), the main port in northeastern French Indochina,and three European tramp shipping companies. When these companies set up a jointagreement in unilaterally increasing the freight rates for shipping rice to HongKong, the affected merchants felt unfairly treated and boycotted the companies’ ships.Furthermore, in , they formed a rival charter syndicate and set up a steamshipcompany chartering the vessels of other companies to apply additional pressure on thefirms to return to the previous rate. Although the Chinese suffered direct financiallosses due to their insufficient expertise in this business, they were successful inachieving a considerable decrease in the freight rate on rice, which shows thatboycotting, even when costly, proved to be an effective means to push for reductionsand better arrangements with shipping companies. In contrast to a similar incident inthe same trade—the shipping boycott of – when the French governmentintervened with the Chinese government on behalf of a French shipping company—the later boycotts did not provoke the intervention of Western powers. This casesuggests that growing anti-imperialism and nationalism in China, expressed in publicdiscourses on shipping rights recovery and in the use of economic instead of politicalmeans, had an impact on the boycotts. Economic, not imperial, power determined theoutcome of this struggle.

Introduction

Rice has been cultivated since ancient times in tropical countries and isthe most widely consumed staple food in Asian countries. In the

Modern Asian Studies () page of . © Cambridge University Press doi:./SX

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

nineteenth century, British rule in India, Singapore, and Hong Kong(pinyin: Xianggang) had established a large free-trade area in Asia thatprovided the market base for the considerable expansion of the ricetrade, for which Singapore and Hong Kong developed into keyredistribution centres. In these and other port cities, Chinese merchantscould be found at all levels of the highly competitive rice export tradeacting as buying agents, millers, and shippers. For Western financialand agency institutions as well as importers and exporters, Chinesedealers also operated as compradors (middlemen) collecting goods andmanaging business. The important role of the Chinese as intermediariesbetween the Europeans and the indigenous people of Southeast Asiancountries and regions was made possible by their high degree ofadaptation to different geographical and social circumstances. Most ofthem had come as migrants from southern China, predominantly fromAmoy (pinyin: Xiamen), Swatow (pinyin: Shantou), and Canton(pinyin: Guangzhou), and established Chinese family firms that wereclosely connected with each other through personal relationships. Thesocial structure and commercial organization of overseas Chinese andthe long history of Chinese trade with Southeast Asia are the mostimportant explanatory factors for the economic predominance of theChinese and the patronage they enjoyed from Western elites. In Saigon(Sài Gòn, currently Ho Chi Minh City; Vietnamese: Thành phô HôChí Minh), Haiphong (Hai Phòng), Hong Kong, and other ports inChina and Southeast Asia, Chinese merchants or ‘hongs’ (factories orwarehouses) dominated the rice trading industry, providing businessservices and connections. These included their links to foreign shippingcompanies and serving as transport providers for shipments of rice andother bulk cargoes overseas.When taking into account the very frequent contact between foreign

and Chinese merchants over a long period of time, which had beenestablished on the basis of mutual interests (the main feature of suchbusiness interactions), it is astonishing to note that there are only a fewstudies on this topic. The main reason is probably the dearth ofprimary sources, especially company and government records dealingwith the microeconomic aspects of ‘on the spot’ daily interactions aswell as their inaccessibility. By presenting a case study in the widercontext of the transnational, maritime, and business history of EastAsia, this article intends to present a more nuanced picture of the rangeof interactions between European tramp shipping companies andChinese rice merchants on the level of material connections—in thiscase, shipping—and on the level of business interactions—in this case,

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

cooperation as a routine occurrence but also conflicts, in the form ofboycotts, as exceptional events.First, this article aims to provide insights into the important role of

European tramp shipping companies as service providers for thetransport needs of Chinese merchant networks in port cities aroundAsia. It will use the examples of two companies operating medium-sizedsteam tramps in East Asian waters from the s until the First WorldWar—one from French Indochina based in Haiphong and one fromGermany with its fleet based in Hong Kong—to highlight that, in thelong run, business relations with Chinese merchants were conducted ona routine and cooperative basis framed by mutual interests. A shippingboycott was an unusual event, as in the case of –, when Chineseshippers in Hoihow and Pakhoi tried to break the temporary monopolyof the French Tonkin Shipping Company by chartering ships from theGerman M. Jebsen Shipping Company.Second, the article will discuss the development and importance of

Haiphong as a major port of Tonkin and the role and position of localChinese merchants in the rice exporting industry and their practice offrequently shipping large cargoes on chartered vessels belonging toEuropean tramp shipping companies. Third, based on archivalevidence, the Haiphong shipping boycotts of and – will bestudied in detail, as will the agreement of May , whichterminated the last boycott. Finally, the historical context in which theboycotts occurred will be explained and some general conclusions willbe drawn from these business interactions, which may be instructive tobetter understand the ways in which both sides cooperated and cameinto conflict with each other under sometimes harsh market economyconditions. What becomes obvious is that the driving force of theHaiphong boycotts of and – was a purely business one,namely, the desire to prevent higher freight charges. Furthermore, thecase study presented here does not support arguments about thedynamics of Western imperial power and Chinese resistance butdemonstrates the non-involvement of European powers at this level ofimperial relations in the east. Rising Chinese anti-imperialism andnationalism, combined with an ongoing public discourse on shippingrights recovery, in employing economic instead of political means,created an atmosphere in which imperial power relations in Chinaaltered significantly. Beginning in , a new generation of smallprivate Chinese shipping companies, strongly committed to shippingnationalism, emerged, mostly operating on small inland rivers. Financedby Chinese capital and flying the Chinese flag, these firms made an

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

argument for shipping autonomy by demonstrating that China could fulfilits own shipping needs without foreign involvement. The discourse ofshipping rights recovery went hand in hand with similar efforts in otherarenas, such as railways and mining, signalling the beginning of a newanti-imperialist era in China.The case study presented here illuminates an almost unknown episode

in East Asian economic history and its transnational dimensions. Thereasons for the obscurity of this episode are perhaps twofold: first, asGerman and French interests (rather than British) were primarilyinvolved, there is scarcely any relevant documentation in the Britishconsular files or Hong Kong government files; second, the German andFrench government files appear to have seldom been consulted byhistorians working on the maritime or business history of East Asia.1

Tramp shipping in East Asia before the Second World War

Until the Second World War, East Asian rice shipping markets weredominated by foreign shipping companies, which, according to statistics,held the largest share of ocean-going and river shipping activities.2

Shipping rights in coastal and inland waters were usually unilaterallydenied to foreigners, but China was forced to grant them due to a seriesof unequal treaties signed with Western powers during the nineteenthcentury. The strong position of Western shipping in Chinese and otherAsian waters in the nineteenth century was, and is, still regarded as asymbol of foreign imperialism. The steamship in particular became notonly a symbol of modernity in transportation but also a ‘tool of empire’,the ‘spearhead of penetration’ in opening up Chinese and other EastAsianmarkets or expressing the ‘politics and processes of semi-colonialism’.3

1 The bulk of material used for this article is derived from the Political Archives of theGerman Foreign Office and the German Federal Archives, both in Berlin; the DiplomaticArchives of the French Foreign Ministry in Paris; the French National Archives of OverseasTerritories in Aix-en-Provence; the Vietnamese National Archives Centre No. in Hanoi,and the private Jebsen and Jessen Historical Archives in Aabenraa. Contemporary Frenchand British newspapers shed further light on the case.

2 L. Hsiao, China’s Foreign Trade Statistics, –, Harvard University Press,Cambridge, MA, , pp. –: Number and Tonnage of Vessels, . InterportTrade [–].

3 F. F. A., ‘Foreign Shipping in Chinese Waters’, Chinese Economic Journal, vol. , no. ,, pp. –; F. Otte, ‘Shipping Policy in China’, Chinese Economic Journal, vol. , no., , pp. –; D. R. Headrick, The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

In their study on Western enterprise in China and Japan, GeorgeC. Allen and Audrey G. Donnithorne present a more nuanced picture,emphasizing the participation of Western ships in the coastal and rivertrade of China. Foreign technological superiority in shipping was themain reason for the extensive use of foreign ships as carriers ofChinese-owned goods and met the existing transport requirements ofChinese merchants. In this area, Chinese and foreigners worked in closecooperation, resulting in the greater part of the cargoes of foreignvessels engaged in China’s domestic trade being carried on the behalfof Chinese merchants.4

In his study on Hong Kong’s development into a global metropolis,David R. Meyer introduced the term ‘trade services’ to define thevarious services provided by well-capitalized firms to unspecialized,small-scale commodity trades, mostly of Chinese merchants, in thenineteenth century. Such trade services, for example, those of theBritish company Butterfield and Swire after , included a shippingline, shipping agencies for other lines, insurance, sales, and bankingagencies, which provided increasing profits for the firm until .These large gains became possible because most Chinese firms hadinsufficient capital to specialize in trade services, especially in owningand operating steamships. In contrast to traditional Chinese junks,which dominated shipments of inexpensive, bulk commodities,5

steamships offered competitive transport for both low- and high-valuecommodities, sufficient insurance, and reliable timetables almost

in the Nineteenth Century, Oxford University Press, New York, , pp. –, –, –,–; J. K. Fairbank, ‘Introduction: Maritime and Continental in China’s History’, inThe Cambridge History of China. Vol. : Republican China, –, Part , J. K. Fairbank (ed.),Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, , pp. –; C. Y. Hsü, The Rise of Modern

China, Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford, , th edn, pp. –;A. Reinhardt, ‘Treaty Ports as Shipping Infrastructure’, in Treaty Ports in Modern China:

Law, Land and Power, R. Bickers and I. Jackson (eds), Routledge, London, New York,, pp. –; A. Reinhardt, Navigating Semi-Colonialism: Shipping, Sovereignty, and

Nation-Building in China, –, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, , p. .4 G. C. Allen and A. G. Donnithorne, Western Enterprise in Far Eastern Economic

Development, Allen and Unwin, London, , pp. –, –.5 On Chinese junk shipping, see A. Reid, ‘Chinese Trade and South East Asian

Economic Expansion in the later Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries:An Overview’, in Water Frontier: Commerce and the Chinese in the Lower Mekong Region, –, N. Cooke and L. Tana (eds), Rowman and Littlefield, Singapore, , pp. –;H. S. H. Choi, The Remarkable Hybrid Maritime World of Hong Kong and the West River Region

in the Late Qing Period, Brill, Leiden, Boston, , pp. –.

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

independent of weather conditions, sea currents, or other unpredictablenatural events.6

Around , the enormous amount of capital required for purchasing,running, and renewing fleets of steamships was rarely available in China.The most noteworthy exception was the China Merchants SteamNavigation Company founded in .7 The general impoverishment ofChina and Southeast Asia (pinyin: Nanyang; lit.: Southern Ocean) andthe insignificant growth of China’s economy from to resultedin services or, more specifically, transport or shipping services, beingprovided by foreign shipping companies. Beginning in the s, theChina Navigation Company of Butterfield and Swire and the IndoChina Steam Navigation Company of Jardine, Matheson and Co.almost monopolized coastal steam shipping markets in East Asia formany years. In the s, major German shipping companies—theNorth German Lloyd and the Hamburg-Amerika Line—beganoperating coastal steamers in these waters. Furthermore, at thebeginning of the twentieth century, Scandinavian, especially Norwegian,shipping companies sent steam tonnage to the Far East, adding to thealready highly globalized Asian shipping markets. Japanese shippingcompanies became increasingly active in these markets after the end ofthe Sino-Japanese War (–) and on an even greater scale after theRusso-Japanese War (–). They created stiff competition byestablishing several coastal and river shipping lines, operatingproprietary ships or chartered vessels under different flags. The mainclients of the shipping companies, namely, low-cost Chinese merchantfirms with limited capital, were part of well-functioning domestic andinternational social networks of capital in Asia. They competed well inthe unspecialized, small-scale commodity intra-Asian trades for whichregular and irregular transport such as small and medium-sized steamcoasters were chartered.8

6 D. R. Meyer, Hong Kong as a Global Metropolis, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,, pp. –.

7 On this Chinese shipping company and the general background of shipping in China,see K. C. Liu, ‘Steamship Enterprise in Nineteenth-Century China’, The Journal of AsianStudies, vol. , no. , , pp. –; K. C. Liu, Anglo-American Steamship Rivalry in

China, –, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, ; K. C. Liu,‘British-Chinese Steamship Rivalry in China, –’, in The Economic Development of

China and Japan: Studies in Economic History and Political Economy, C. D. Cowan (ed.), Allenand Unwin, London, , pp. –.

8 A. Feuerwerker, ‘The Foreign Presence in China’, in The Cambridge History of China, Vol.

, pp. –; J. Osterhammel, China und die Weltgesellschaft: Vom . Jahrhundert bis in unsere

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

Such vessels were usually steam tramps capable of picking up freightand passengers at widely scattered ports and transporting them arounddifferent regions. These ships were particularly important in bulktrades, such as rice, coal, tea, sugar, beans, grains, and othercommodities. In view of steam tramps’ important role in cabotage(coastal trade), it is remarkable that there seems to be no comprehensivestudy on the subject and very few case studies to provide a fullerpicture.9 In this article, two tramp shipping companies and their steamtramp operations in East Asia will be more closely evaluated: theTonkin Shipping Company, an affiliate of the partnership firm ofMarty et d’Abbadie based in Haiphong, which mainly operated in thewider Gulf of Tonkin region,10 and the M. Jebsen Shipping Company,

Zeit, Beck, Munich, , pp. –; Meyer, Hong Kong as a Global Metropolis, pp. –.For recent discussions on the importance of Chinese intra-Asian trading networks, seeT. Hamashita, China, East Asia and the Global Economy: Regional and Historical Perspectives,L. Grove and M. Selden (eds), Routledge, London and New York, ;E. Tagliacozzo and W.-C. Chang (eds), Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities and

Networks in Southeast Asia, Duke University Press, Durham, NC, ; U. Bosma andA. Webster (eds), Commodities, Ports and Asian Maritime Trade since , PalgraveMacmillan, Houndsmills, .

9 J. Armstrong, ‘Coastal Shipping: The Neglected Sector of Nineteenth-Century BritishTransport History’, in his The Vital Spark: The British Coastal Trade, –, InternationalMaritime Economic History Association, St. John’s, Newfoundland, , pp. –.

10 The Tonkin Shipping Company (Compagnie Tonkinoise de navigation) was set up inHaiphong in as an affiliate of Marty et d’Abbadie, founded in by AugusteRaphael Marty (–) and Édouard Jules d’Abbadie (–). In Hong Kong,Marty’s trading firm, A. R. Marty, acted as agent of the Tonkin Shipping Company,which, in , purchased two new British-built steamers and, in and , fourused steam tramps, employing them for its ocean-going services. In , the TonkinShipping Company won the subsidy contract for the Kwang-chow-wan postal steamerservice frequently linking Haiphong with France’s leased territory Kwang-chow-wan(pinyin: Guangzhouwan; today: Zhanjiang) located in China’s Kwantung Province.Another affiliate of Marty et d’Abbadie was the Subsidised River Shipping Service ofTonkin (Le service subventionné des correspondances fluviales du Tonkin), which from to employed a fleet of river ships operating on the Red River and itsestuaries. In Haiphong, Marty et d’Abbadie had a dockyard and workshops forrepairing ships. The history of Marty et d’Abbadie is only sparsely documented; theearliest substantial reference is to be found in the special edition of the Haiphong-basednewspaper Le Courrier d’Haiphong: Supplément – au Millième Numéro du Journal, December , pp. –. Brief overviews of Marty et d’Abbadie’s commercial activitiesin Indochina and China and in the local context of Haiphong are available inR. Dubois, Le Tonkin en , Société Française d’Éditions d’Art, Paris, , pp. –; G. Raffi, ‘Haiphong: origines, conditions et modalités du développement jusqu’en’, PhD thesis, vols, Université de Provence, , Vol. , pp. –; V. K. Tran,

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

whose Hong Kong-based fleet operated along the China coast andits vicinity.11

In the wider Gulf of Tonkin region—the northwestern part of the SouthChina Sea stretching between the Red River delta (also called the Tonkindelta) of French Indochina and the Pearl River delta of South China (seeFigure )—the two shipping companies embodied Western dominance inshipping in China. The maritime region was, around , thicklyinterconnected by a multitude of ships plying between five main ports:Haiphong (Hai Phòng), the shipping hub of Tonkin, with its major riceexporting industry; Pakhoi (pinyin: Beihai) and Hoihow (pinyin:Haikou), the open Chinese ‘treaty ports’, mainly exporting vegetablesand cattle to Hong Kong and South China; Canton (pinyin:Guangzhou), the traditional commercial hub of South China and atreaty port; and Hong Kong, the British crown colony at the mouth ofthe Pearl River, with its important international free port serving as aneconomic turnstile at the crossroads of intercontinental andinterregional shipping routes. One of the most important bulk cargoes

‘L’industrialisation de la ville de Haiphong de la fin du XIXe siècle jusqu’à l’année

(L’invention d’une ville industrielle en Asie du Sud-Est)’, PhD thesis, UniversitéAix-Marseille, , pp. –.

11 The M. [Michael] Jebsen Shipping Company (Reederei M. Jebsen) was founded in in Apenrade, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, by Michael Jebsen (–) andsuccessively transferred its modern fleet of medium-sized merchant steamships to theFar East, where the ships were chartered by Chinese and European merchants totransport all sorts of cargo and passengers between coastal ports in East Asia. TheJebsen steam tramps were specially equipped for shipping bulk goods (rice, coal, wood,vegetables, and cattle), with a low draught capable of entering the typically very shallowChinese ports. In , after all ships had been transferred to Hong Kong, its steamerfleet numbered eight; in –, the company reached its peak with ships, and by, the company had ships. Starting in March , the principal agent of theM. Jebsen Shipping Company was Jebsen and Co. Ltd. in Hong Kong, owned byJacob Jebsen (–, son of Michael Jebsen) and his business associate JohannHeinrich Jessen (–). Jebsen and Co. Ltd., having started in as a shippingagency and general trading company, soon occupied a leading position in foreign tradein China and Hong Kong. The early years of the M. Jebsen Shipping Company aredealt with in E. Hieke, Die Reederei M. Jebsen A.G. Apenrade, Hamburgische Bücherei,Hamburg, ; A. von Hänisch, Jebsen and Co. Hongkong: China-Handel im Wechsel der

Zeiten –, Private Print, Apenrade, , pp. –; L. Miller andA. C. Wasmuth, Three Mackerels: The Story of the Jebsen and Jessen Family Enterprise,Hongkongnow.com, Hong Kong, , pp. –; B. Becker, ‘Coastal Shipping in EastAsia in the Late Nineteenth Century’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch,vol. , , pp. –; B. Becker, Michael Jebsen: Reeder und Politiker, –: EineBiographie, Ludwig, Kiel, , pp. –.

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

frequently transported from French Indochina to Hong Kong was rice. Itwas produced and harvested primarily in the region around the Mekongdelta, with Saigon as the main export centre, and on a smaller scale in themore densely populated regions of Annam and Tonkin, the northern partsof Indochina.In the s, Marty’s firm in Hong Kong also frequently chartered

tramps under the German (including vessels from Jebsen’s fleet) andDanish flags.12 The chartering of steam tramps occurred on the basis oftrip (or voyage) charters or time charters: in the first case, the charterer(or shipper) hired the vessel for only one voyage to carry his cargo at anagreed rate per ton; in the second case, the shipowner provided thecrew and all other requirements to operate the ship. The chartererbecame the disponent owner and was usually allowed to send the vesselin any direction and load it with all kinds of permitted merchandise, aswas typical in tramp shipping. There were no fixed fares for passengersor cargoes, but the rates for freight depended on the conditions of themarket. Tramping was, as maritime historian Michael M. Millerexplains, ‘a constant struggle to position ships where freight was

Figure . Detail of a map of China showing the wider Gulf of Tonkin region in the earlytwentieth century. Source: The Hundred and Twentieth Report of the London Missionary Society,London Missionary Society, London, .

12 M. H. Bach, ‘Randersskibe på Kinakysten’, Årbog , Museum Østjylland (ed.),Narayana, Randers, , pp. –.

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

abundant and competitors’ ships were not, where rates therefore werehigh not low, where voyages contracted would not undercut arrival intime for seasonal trades, where going for a “spot loading” was betterthan fixing a cargo in advance’.13

As research into the operations of the two aforementioned trampshipping companies in the period from the s to reveals,routine dealings with Chinese shippers and charterers were conductedon a well-functioning, professional basis. Friendly relations were onlystrained when outside factors became imminent, such aspolitical-imperialistic considerations. Such an instance occurred in – when, during the Sino-Japanese War (–), the TonkinShipping Company exploited the temporary lack of available steamtonnage for rice shipments on the Haiphong-Hong Kong run andattempted to monopolize the coastal steaming routes in the wider Gulfof Tonkin region. Marty’s attempt prompted Chinese shippers in portcities to form a charter syndicate to effectively boycott his ships.Instead of Marty’s ships, the Chinese chartered steamers from the

M. Jebsen Shipping Company. This event resulted in an agreement aboutthe joint organization of shipping services between the Chinese shippingcompany Yuen Cheong Lee and Co. (源昌利) in Hong Kong, owned bythe Hainan-born merchant Chau Kwang Cheong (周昆章), and theM. Jebsen Shipping Company, represented by Jebsen and Co., paving theway for close cooperation between the firms for many years. Although theFrench succeeded in inducing the Qing government to compensateMarty, his business relations with Chinese shippers were ruined for sometime. Strong backing by an imperialist power such as France was notnecessarily advantageous for foreign business in China. Marty’s attemptto monopolize the highly profitable rice shipping route was not in theinterest of Chinese shippers, in whose view the unilateral action of theFrench shipowner destroyed a mutually beneficial relationship.14

Similar incidents were the Haiphong shipping boycotts of and–. In this case, Chinese charterers in Haiphong again formed acharter combine and even founded their own shipping company toeffectively boycott a German, a French-Indochinese, and a British

13 M. B. Miller, Europe and the Maritime World: A Twentieth-Century History, CambridgeUniversity Press, Cambridge, , p. .

14 B. Becker, ‘France and the Gulf of Tonkin Region: Shipping Markets and PoliticalInterventions in South China in the s’, Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture

Review, vol. , no. , November , pp. –. The electronic version can be foundat: https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-/becker, [accessed July ].

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

tramp shipping company. In consular files, business correspondences, andcontemporary newspapers, the said events are exclusively referred to as‘shipping boycotts’ or just ‘boycotts’, terms that are also used in thisarticle to characterize these conflict-laden business interactions. Earlylocal boycotts in China—often called ‘taboos’ in English-languagesources—were not directed against the ships of a particular nation butagainst those of a particular company. In this respect, such boycottswere different from the well-known greater boycotts used by theChinese to target Japan, the United States, and Britain in particularfrom the s to the s. The early boycotts can be regarded as theweaponry of one of the most powerful and organized social groups inlate Qing China, namely, the Chinese merchant guilds. Guild membersentered into agreements that involved ceasing to purchase or deal ingoods or abstaining from the use of ships belonging to the boycottedcountry.15 A similar practice, but with the aim of targeting a specificshipping company, can be observed when looking at the –boycott in the wider Gulf of Tonkin region. The same pattern wasapplied in the Haiphong shipping boycotts of and –, whenboycotts by Chinese rice merchants were directed against threeEuropean tramp shipping companies after they unilaterally increasedfreight rates.

Haiphong and the Chinese rice merchants

Haiphong, situated in the northeastern coastal area of the Indochinesepeninsula, is currently the third-largest city in Vietnam and a majorindustrial centre. In the mid-nineteenth century, Haiphong was merelya native village with a market located at the confluence of the SongCua Cam (Forbidden River; in Vietnamese: Sông Cua Cam) and theSong Tam Bac (Sông Tâm Băc) in Lower Tonkin, a region that at thetime formed part of Vietnam and was ruled by emperors of theNguyen dynasty. Since the Song Cua Cam is interlinked with the RedRiver (Sông Hông), the main waterway of Tonkin, Haiphong was thegateway to Hanoi (Hà Nôi) when French military forces entered the

15 H. B. Morse, The Guilds of China, Longmans, Green, London, , pp. –;C. F. Remer, A Study of Chinese Boycotts: With Special Reference to their Economic Effectiveness,Cheng-Wen, Taipei, , pp. –; S. K. Wong, China’s Anti-American Boycott Movement

in : A Study in Urban Protests, Lang, New York, .

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

region in the s. After the French had occupied Hanoi and otherstrategic sites in the delta, the treaty of March , among otherstipulations, compelled the Vietnamese emperor to make Haiphong aFrench concession. The village was opened to foreign commerce, aFrench consul appointed, and a mixed French-Vietnamese customsoffice set up. A few French export firms were established in the newconcession that shipped rice to Hong Kong, but export figuresremained on a small scale. At the time, only approximately

Chinese were estimated to reside in Haiphong. The main reason for theweak presence of Chinese merchants—the traditional controllers ofIndochina’s rice trading industry—was the commercial policy of theVietnamese government: between and , it issued a series ofbans on the export of rice from Haiphong. This move was obviouslydesigned to disadvantage the French concession of Haiphong and tofavour exports from neighbouring Nam Dinh (Nam Đinh), which wasunder Vietnam’s full control.16

Chinese people havemigrated to the Indochinese Peninsula since the earliesttimes, often as a result of population pressure and political upheavals in China.The frequent immigration waves resulted in the creation of a newSino-Vietnamese ruling class and in strong influences of Chinese culture andthinking on Vietnam. In the economic sector, the Chinese were active inagriculture and trade, benefiting, as Alain G. Marsot explains,

from the greater cultural and commercial sophistication of their mother country,in terms of its very size and greater economic development, compared to thesmall and scattered societies of Southeast Asia. Furthermore, those Chinesemerchants continued to maintain close ties with their families and kinshiporganizations in China, and in general with the trading communities there,thereby occupying a naturally privileged position as intermediaries between theSouth China markets and those of Southeast Asia. They were to maintain thatposition throughout the European period.17

16 C. de Kergaradec, ‘Rapport sur le commerce du port de Haiphong pendant l’année’, in Cochinchine française: Excursions et Reconnaissances, no. , Imprimerie duGouvernement, Saigon, , pp. –; C. Robequain, The Economic Development of

French Indo-China, Oxford University Press, London, (the French edition waspublished in ), p. ; Raffi, ‘Haiphong’, Vol. , pp. –; J. Martinez, ‘ChineseRice Trade and Shipping from the North Vietnamese Port of Hai Phòng’, Chinese

Southern Diaspora Studies, vol. , , pp. –; P. Brocheux and D. Hémery, Indochina:An Ambiguous Colonization, –, University of California Press, Berkeley, (theFrench edition was published in ), p. .

17 A. G. Marsot, The Chinese Community in Vietnam under the French, Edwin Mellen,San Francisco, , pp. – (the quote: p. ).

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

What seems to have further contributed to the strong position of theChinese in Vietnam were certain human capacities, most importantlyflexibility and great adaptability. Compared to the Vietnamese, asMarsot states, ‘they often shared the qualities of the local people,though to a higher degree perhaps, combining them with greaterastuteness, obstinacy and method’.18 In his doctoral law thesis of ,René Dubreuil laid out that ‘the Chinese indeed behave in Indochinaas a kind of germ stimulating production and through that creatingwealth’, whereas the Vietnamese ‘do neither possess the initiative northe mental curiosity honed by the lure of profit, something that drivesthe Chinese to searching for new products which are likely to providethem with a profit’.19

As a result of the Sino-French War (–) and the subsequenttreaties with the Vietnamese and Chinese governments, French controlwas fully established in Annam and Tonkin. With the constitution ofFrench Indochina, or of the Indochinese Union (in French: Union del’Indochine française), enacted by decree on November , theprotectorates of Annam and Tonkin, with a resident superior at the top,became part of the new political unit administered exclusively by theFrench Ministry of Colonies and under the direct authority of agovernor-general. Haiphong, having served as a port of debarkationand supply for the French expeditionary force during the militaryoperations, became the centre of the French navy in northernIndochina. Among the first private companies, founded in Haiphongnear the naval shipyard, was the aforementioned partnership firm ofMarty et d’Abbadie, which developed into one of the pioneeringenterprises of colonial Tonkin.20

With the Sino-French treaty of June , Chinese settlers weregranted the right of free entry and were allowed to run commercialoperations in Indochina. In the same year, an immigration office andinformation bureau were set up in Haiphong to tackle the influx offoreigners. With that step, the French continued the practice of theVietnamese emperors, who had given a privileged status to Chineseresidents. Following the French occupation of Indochina, which

18 Ibid., pp. – (the quote: p. ).19 R. Amer, The Ethnic Chinese in Vietnam and Sino-Vietnamese Relations, Forum, Kuala

Lumpur, , pp. –; R. Dubreuil, De la Condition des Chinois et de leur Rôle économique en

Indo-Chine, Saillard, Bar-sur-Seine, , pp. –, – (the quote: p. ).20 Robequain, The Economic Development, pp. –; Raffi, ‘Haiphong’, Vol. , pp. –;

Brocheux and Hémery, Indochina, pp. –.

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

established order and security and stimulated economic activity, Chineseimmigration was further encouraged, especially from the southernChinese provinces of Kwangtung (pinyin: Guangdong), Fukien (pinyin:Fujian), and the island of Hainan, to foster commercial relationsbetween Tonkin and South China. Upon their arrival, Chineseimmigrants were admitted into a congregation (French: congrégation), aself-administered Chinese community, based on their dialect and/orprovince of origin in China.21 In Vietnam, the number of Chinese rosefrom , in to , in , but in northern Vietnam, theChinese were not nearly as numerous as they were in the south: in

there were , Chinese in Tonkin, of which , were people ofmixed Chinese-Vietnamese origin called Minh-Huong (French: métis).22

This trend was largely due to the overpopulation of the Tonkin andAnnam deltas and the subsequent relatively small export of agriculturalproducts, one of the greatest economic interests of the Chinese. InHaiphong, the number of Chinese increased from , in to, in , which constituted per cent of the local population inthe latter year.23

21 The Chinese congregations in Vietnam originated from the system ofself-administered ‘bangs’ created in to allow the Vietnamese emperors to directlyand indirectly control Chinese settlers. Chinese officers, called ‘bang truong’, chosen bymembers of the ‘bang’, were held responsible by the Vietnamese authorities for thegood behaviour of their ‘bang’ members and for the payment of taxes. The French,renaming ‘bangs’ to ‘congrégations’, maintained the system; in Hanoi and Haiphong,two Chinese congregations, Canton and Fukien, were legally recognized by the Frenchauthorities. The heads of the congregations played a central role in the fields of publicorder and taxation, and in social and cultural activities. However, congregations werenot permitted to engage in commercial activities. Dubreuil, De la Condition des Chinois et

de leur Rôle économique en Indo-Chine, pp. –, –; Q. D. Nguyen, Les Congrégations

Chinoises en Indochine Française, Recueil Sirey, Paris, ; Marsot, The Chinese Community,pp. –, ; R. Amer, ‘French Policies towards the Chinese in Vietnam: A Study ofMigration and Colonial Responses’, Moussons: Social Science Research on Southeast Asia, vol., –, pp. –, –.

22 Amer, ‘French Policies’, p. , Table : Number of Chinese in Vietnam to

by regions, and p. , Table : Number of Minh-Huong/métis in Vietnam to .23 After the creation of the protectorates of Annam and Tonkin, Haiphong saw a steady

rise in population, mainly of Vietnamese people. Haiphong’s total population was , in, , in , and , in . While from to , the percentage of theVietnamese inhabitants rose from per cent to per cent, the percentage of Chinese fellfrom per cent to per cent, and the percentage of Europeans rose from per cent to

per cent. In , the Vietnamese constituted per cent of the local population, theChinese per cent, and the Europeans per cent. There was also a very marginalgroup consisting of only people in who may have been Minh-Huong not born

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

Immediately after the occupation of Tonkin, the French authorities setup customs depots in Haiphong, Hanoi, and Nam Dinh, and, inNovember , decreed that all rice exported from Tonkin should bechannelled through Haiphong and that overseas shipping of rice shouldbe limited to the period from December to March each year when ricewas available in larger quantities.24 The restriction of rice exports toHaiphong as the prime outlet contributed enormously to thedevelopment and prosperity of the town and helped to transform itsharbour into the major port of Tonkin (see Figure ).25

By the early twentieth century, the port had undisputedly become themost important commercial outlet of Tonkin, being well connected toits hinterland by river shipping services and railway lines, and overseasvia coastal and ocean-going shipping links. Rice exports from Haiphongprofited from the long period of political peace and stability in Asia,which only ended with the outbreak of the Second World War.Increasing the prosperity of the port were the frequent water regulationand improvement works undertaken in the Red River delta, theconstruction of modern and steam-driven rice mills, the availability ofsufficient and efficient steam shipping tonnage for the bulktransportation of rice, and, last but not least, the installation oftelegraphs for the rapid ordering of rice shipments (see Figure ).26

in Haiphong, Hanoi, or Tourane: see Raffi, ‘Haiphong’, Vol. , p. , Table :Population of Haiphong –; the latter group is listed as ‘diverse’. Minh-Huongborn in these cities had the nationality of their fathers according to the decree of issued by the governor-general of Indochina: see Amer, ‘French Policies’, pp. –.

24 In Annam and Tonkin, there were usually two rice harvests per year (in June andNovember), but due to the overpopulation of these regions and changing weatherconditions, the rice supply varied, with the result that only the autumn harvest wassuitable for exportation. G. Dauphinot, ‘Le Tonkin en ’, Bulletin Économique de

l’Indochine, vol. , July–August , p. ; Inspection Générale des Mines et del’Industrie, L’Indochine Économique, Imprimerie d’Extrême-Orient, Hanoi, , p. .

25 Infrastructural measures aimed at supporting large-scale trading included theconstruction of a three-kilometre-long canal cutting through the town, an exclusivelyEuropean port situated on the Song Cua Cam and a Chinese port on the Song TamBac. Raffi, ‘Haiphong’, Vol. , pp. –, , –; Martinez, ‘Chinese RiceTrade’, p. ; Tran, ‘L’industrialisation’, pp. –.

26 In , the total number of ocean-going ships entering the port of Tonkin was ,at , net register tons; in the same year, Saigon counted vessels, at almost .million tons, and Hong Kong ,, at more than million tons. In , Hong Kongcounted almost , vessels accounting for almost million tons, while Saigon’snumber of vessels had increased to , at . million tons, and Haiphong’s to ships,at , tons. These figures demonstrate that despite Haiphong’s economic

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

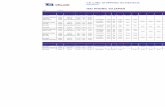

Rice was the French colony’s most important export product, and itsproduction was divided between a very large number of Vietnamesepeasants. In the early twentieth century, exports from Haiphong weredominated by local Chinese merchants, most of them Cantonese,essentially assuring the commercial success of the port. In ,

Chinese rice merchants were listed in the official records of Haiphong,all but one of whom were located in the Rue Chinoise (Chinese Street;see Figure ), in close proximity to the Chinese port.27 Their dominant

Figure . The port of Haiphong, around . Source: Private collection of Bert Becker.

development, it did not reach the levels of Hong Kong and Saigon, its neighbouring portcities in South China and Indochina. Raffi, ‘Haiphong’, Vol. , pp. –.

27 The Chinese in French Indochina were prohibited from engaging in any industry thatdirectly competed with French investments. Therefore, they mainly engaged in the fishingsector, in trade, and in industries related to rice. In in Haiphong, Chinese and

Europeans held ‘patents’ (trading licences); of the , licences issued to Vietnamese, mostwere in retail trades. Raffi, ‘Haiphong’, Vol. , p. ; Martinez, ‘Chinese Rice Trade’,p. ; Amer, ‘French Policies’, p. . For general aspects of Chinese rice trading, seeF. V. Field (ed.), Economic Handbook of the Pacific Area, Doubleday, Doran, New York,, pp. –; V. Purcell, The Chinese in Southeast Asia, Oxford University Press,Kuala Lumpur, , nd edn, pp. –; A. J. H. Latham, ‘From Competition toConstraint: The International Rice Trade in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries’,Business and Economic History, second series, vol. , , pp. –; R. E. Elson,‘International Commerce, the State and Society: Economic and Social Change’, in

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

position in the local rice trading industry was highlighted in early inan article in The Hongkong Telegraph, which was critical of the FrenchIndochinese government’s position towards the Chinese in Tonkin: ‘Itcan be fairly maintained that the organization of Chinese rice buyersand shippers in Tongking [Tonkin] is one of the best in the East, andthe real commerce of that place, both import and export, depends

Figure . Haiphong centre with Boulevard Paul Bert and the cathedral, around .Source: Private collection of Bert Becker.

The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Vol. , Part : From c. to the s, N. Tarling (ed.),Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, , pp. , –. Recent works on riceexportation from French Indochina and the important functions of various Chinesemerchant houses and their cooperative and competitive business relations with Frenchcolonial enterprises include K. Vorapheth, Commerce et Colonisation en Indochine (–): Les Maisons de Commerce Françaises, un Siècle d’Aventure Humaine, Les Indes Savantes,Paris, , pp. –; P. Brocheux, Une Histoire Économique du Viet Nam –: laPalance et le Camion, Les Indes Savantes, Paris, , pp. –; G. Sasges, ‘Scaling theCommanding Heights: The Colonial Conglomerates and the Changing PoliticalEconomy of French Indochina’, Modern Asian Studies, vol. , no. , , pp. –,–; C. Goscha, The Penguin History of Modern Vietnam, Penguin, Milton Keynes,, pp. –. For the Hong Kong rice merchants, see D. Faure, ‘The Rice Tradein Hong Kong before the Second World War’, in Between East and West: Aspects of Social

and Political Development in Hong Kong, E. Sinn (ed.), Centre of Asian Studies, Hong Kong,, pp. –.

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

mainly on the enterprise and industry of the Celestial [Chinese].’ Thewriter praised the ‘proverbial integrity of the Chinese merchant’ inTonkin, concluding with the statement that ‘for truly they are thestrength of the land, this hard-working uncomplaining race’.28

From to —a period of relatively good rice harvests—,tons of rice on average were exported from Haiphong, while in the sameperiod Saigon exported , tons; Saigon’s rice export was generallyfive to six times higher than that of Haiphong and this patterncontinued until the s. With catastrophic weather conditionsdestroying large quantities of rice in Tonkin between and ,exports from Haiphong reached their nadir in the latter year, with only, tons exported, the lowest figure since . Most rice exportswent to Hong Kong, which further enhanced its superior position asthe prime distribution centre in the South China Sea. Economically,

Figure . Chinese Street in Haiphong, around . Source: Private collection ofBert Becker.

28 ‘The Chinese in Tongking’, The Hongkong Telegraph, January ; republished andtranslated in French as ‘Les Chinois au Tonkin’, Revue Indo–Chinoise, February ,pp. –.

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

Haiphong, to a large extent, entirely depended on its connections withHong Kong.29

With their dominant position in the Haiphong rice trade, the Chineserice merchants also controlled the bulk of rice shipments, which wereconducted by shipping hongs, with trading and shipping typicallycarried out by the same firm. These Chinese shipping hongs arrangedtransport, which made them comparable to freight forwarders in otherparts of the world. As Michael B. Miller established when evaluatingthe business operations of Butterfield and Swire in Asia, ‘The range ofservices’ of Chinese hongs, ‘from banking to documentation, was socomprehensive that few shippers were prepared to save on commissionsand negotiate directly with foreign shipping companies’.30 In this way,hongs located in major trading centres provided business services andconnections when managing shipments from Haiphong to Hong Kongand other destinations. These services enhanced their already powerfuleconomic position within the local Chinese community of Haiphongand among other rice traders.

The first Haiphong shipping boycott,

Compared to the often relentless competition in other shipping markets inthe Far East, the situation of that in the wider Gulf of Tonkin region wasin some ways privileged: until early , the firms of Jebsen and Martyshared between themselves almost all the traffic.31 By a kind of tacitagreement, the freight and passage prices of their steam tramps weremore or less equal, preventing ruinous competition against each

29 Raffi, ‘Haiphong’, Vol. , pp. –, , ; C. Fourniau, Vietnam: DominationColonial et Résistance Nationale (–), Les Indes Savantes, Paris, , pp. –;Brocheux, Une Histoire Économique du Viet Nam, p. .

30 Miller, Europe and the Maritime World, p. .31 In , a total of vessels called at the port of Haiphong, of which flew the

French flag; , the German flag; and , the British flag; the remaining vessels wereunidentified and probably consisted of local junks and other small carriers. In ,German ships, with calls, dominated the port of Haiphong, compared to Frenchand British calls. Even in the following year, when rice exports reached theirten-year low, the German flag again had the upper hand with calls, while theFrench fell back to ships calling; only ships British ships called at Haiphong.Raffi, ‘Haiphong’, Vol. , pp. , .

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

other.32 Such an arrangement between tramp shipping companies wassomewhat similar to the agreements—so-called conferences—amongliner companies in overseas shipping running to a fixed schedule in aparticular trade. However, since steam tramps usually ‘did not ply oneregular route but rather worked whatever cargo and route wasavailable, making mutual pricing a nightmare’, tramp conferences ‘wereunlikely to succeed’, explains maritime historian John Armstrong.33 Inthis light, the tacit agreement between Jebsen and Marty was a specialcase, but it certainly prevented a price war. Whether the existingsituation was to the disadvantage of Chinese merchants chartering theships of Jebsen and Marty or instead helped to preserve stable marketconditions with two competitors still in the field remains an open question.The expectation that serious competitors would not emerge was

violated with the sudden appearance of the China NavigationCompany, the shipping arm of Butterfield and Swire, at the timegenerally regarded as the most powerful shipping company in EastAsia.34 Until then, the firm was mainly active in northern China, whereit competed with Japanese shipping companies for lucrative freights.Since the company papers of that specific business during this periodare not available,35 the concrete reasons for the firm’s decision to send

32 Diplomatic Archives of the Foreign Ministry [Affaires Étrangères ArchivesDiplomatiques, Paris, France]: AEAD, Correspondance politique et commerciale, –, Nouvelle Série: Chine, vol. : René Teissier-Soulange (in charge of the FrenchConsulate in Hong Kong) to Foreign Minister Stéphen Pichon (Paris), April .The Hong Kong Telegraph, April , reported on this agreement as follows: ‘It is amatter of little moment to the ordinary reader whether a written compact was enteredinto between the two foreign firms as to the freight rate to be maintained. To theshipper and the consignee, however, it was well-known that such an understandingexisted and for the three years that the French and German firms ran steamers infriendly rivalry their uniform charge was one of cents per picul.’

33 J. Armstrong, ‘Conferences in British Nineteenth-Century Coastal Shipping’, in hisThe Vital Spark, p. .

34 In , Butterfield and Swire, a well-established British trading house in China,founded the China Navigation Company, which soon became the major shippingcompany in Far Eastern waters. On its history, see S. Marriner and F. E. Hyde, TheSenior John Samuel Swire, –: Management in Far Eastern Shipping Trades, LiverpoolUniversity Press, Liverpool, ; Miller, Europe and the Maritime World, pp. –. In theconsulted French, German, and British consular files, the shipping company isexclusively referred to as Butterfield and Swire or only as Butterfield, a modus operandithat is also used in this article.

35 The Swire Archives, kept by SOAS, University of London, do not contain anyrelevant papers on such aspects.

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

its ships to southern China remain unclear. However, two factors certainlyplayed an important role: first, by mid-, the worst recession in decadeshad hit the world’s shipping industry, severely affecting shippingcompanies operating in East Asia as falling freight rates increasedcompetition among them. Second, in September , the Japanesegovernment initiated the merger of four Japanese shipping companiesoperating on the Yangtze River (pinyin: Chang Jiang) into the newlyformed firm Nisshin Kisen Kaisha (Japan-China Steamship Company),which soon dominated the Yangtze business. The appearance of thisstrong competitor had severe consequences for Butterfield and Swire, asbusiness historian William D. Wray explains: ‘it seems to have greatlyreduced their profits, which were already heading downward as a resultof the depression. Between and , the China NavigationCompany [of Butterfield and Swire] did not earn enough to coverdepreciation charges on its fleet and could not pay a dividend.’36

Contemporary observers speculated that the increasingly strong positionof the Japanese flag after the end of the Russo-Japanese War (–),which put other flags out of business, and the expectation of Butterfieldand Swire obtaining higher profits in this new market triggered thedecision to open up a new shipping service between Hong Kong,Hoihow, and Haiphong. The British firm officially informed Jebsen andCo. about the planned step beforehand in April , and asked forconfidential information about the German firm’s freight tariffs, whichit received. At the time, Jebsen and Marty had fixed the freight rate onrice at cents per rice bag (equivalent to one Chinese picul or

kilograms) and granted shippers the return commission of per centon the amount of the freight, to be paid at the end of every year.37

As a result of Butterfield’s approach, both companies set up atemporary contract for identical lower rates for their rice shipments,

36 W. D. Wray, Mitsubishi and the N.Y.K., –: Business Strategies in the Japanese

Shipping Industry, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, , pp. , – (thequote: p. ); E. S. Gregg, ‘Vicissitudes in the Shipping Trade –’, The

Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. , no. , , p. .37 Federal Archives, Berlin [Bundesarchiv, Berlin, Germany]: BAB, Auswärtiges Amt

(AA), R-: Consul Hans von Varchmin (Pakhoi) to Chancellor Bernhard Princevon Bülow (Berlin), June ; BAB, AA, R-: Consul Hans von Varchmin(Pakhoi) to Chancellor Bernhard Prince von Bülow (Berlin), November ; AEAD,Chine, vol. : René Teissier-Soulange (in charge of the French Consulate in HongKong) to Foreign Minister Stéphen Pichon (Paris), April ; BAB, AA, R-:Johann Heinrich Jessen, Bericht über den Stand der südchinesischen Küstenfahrt [Report on thesituation of coastal shipping in South China], October .

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

namely, a reduction from cents to cents per rice bag. With adecrease of per cent, the British firm obviously expected to quicklyfind sufficient transports to position itself firmly in the rice shipmentmarket in the Gulf of Tonkin, and to stave off the much-fearedcompetition from Japanese shipping companies.38 However, the newagreement became another step towards a full-scale shipping conferenceafter Jebsen agreed to the deal, fearing a ruinous price war with theBritish company should he, with his smaller firm, not consent. Theagreement was valid until Marty decided whether he wanted to join it.Although the Frenchman was considered relatively unfit for businessand his days with his firm almost at the end, Jebsen feared that ifMarty was pushed out of business in this market, France would replacehis firm with a stronger rival that, with the help of French subsidies,would be able to drive Jebsen out of the market, especially if theFrench combined with the British.39

After this agreement with Jebsen was made and Marty had agreed tojoin it, the British shipping company officially announced that it wouldlaunch the new service in early June .40 The joint agreementworked smoothly, but the relatively low freight rate of cents per ricebag, as agreed upon by the three companies, negatively affectedMarty’s company, which suffered from increasing losses. Marty’s firmworked less economically than Jebsen’s and Butterfield’s as the lattertwo possessed larger and more modern fleets of steamships, which

38 The National Archives, Kew, UK: TNA, Foreign Office: FO -:G. W. Pearson, Acting Consul (Kiungchow), to Sir John Jordan, British Minister(Peking), May .

39 Such hopes were indeed expressed in an article titled ‘Against the Germans’published in June in the Haiphong press. Referring expressively to the ‘EntenteCordiale’—the Anglo-French entente of April —the writer stated that, thanks tothis agreement, France in the Far East had the least to fear from Britain, whosesuccessful struggle with Germany would also be beneficial and helpful for France.‘Lettre d’Hoihow: Contre Les Allemands’, Le Courrier d’Haiphong, June . Thisnewspaper, of which Marty was one of the founders in , was the mouthpiece of theFrench community of Haiphong, representing its members’ specific views and opinions,with an emphasis on promoting local business interests. One of its frequently repeatedissues was the fight against the project to replace Haiphong as the main port hub ofTonkin with another nearby location. G. de Gantès, ‘Coloniaux, gouverneurs etministres: L’influence des Français du Viet-Nam sur l’évolution du pays à l’époquecoloniale –’, PhD thesis, vols, Université de Paris VII Denis Diderot, ,Vol. , pp. –.

40 AEAD, Chine, vol. : French Minister Edmon Bapst (Peking) to Foreign MinisterStéphen Pichon (Paris), June .

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

provided them with greater flexibility and more profitable businesses.41

However, no additional agreements, such as on the number of shipsthat each firm was permitted to put on the service, were made.Freight rates during remained relatively low, as had been agreed

upon by the three companies, resulting in continuously low profits.Obviously at Marty’s initiative, on November , the three firmscame to a new joint agreement on a revised uniform freight rate of cents per rice bag. This actually restored the rate to the same level asbefore Butterfield had entered the market some months earlier.However, Chinese rice shippers in Haiphong regarded this decision asunacceptable and immediately decided to boycott the ships of the threefirms. The first ship affected was Butterfield and Swire’s Singan, whichdid not receive any freight on November and lay idle in theport of Haiphong; shortly afterwards, the same fate befell vesselsbelonging to Jebsen and Marty. The Hong Kong Telegraph, when reportingon the incident and its background, was convinced that the tactics of‘eminent practical common sense’ adopted by the Chinese ricemerchants in Haiphong would ‘certainly go to show their determinationto fight the Conference’.42 The newspaper also made it known that theShun-Tai rice company at Haiphong, through its Hong Kong agent PoHing Tai, had instead chartered two steamers—the Fritjof and the Dagny

—in Hong Kong under the Norwegian flag,43 offering rice shippers the

41 Political Archives of the Foreign Office [Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts,Berlin, Germany]: PAAA, Deutsche Botschaft in China (Peking II), Peking II-:Consul Dr Rudolf Walter (Pakhoi) to Chancellor Bernhard Prince von Bülow (Berlin), June ; Jacob Jebsen (Hong Kong) to Consul Hans von Varchmin (Pakhoi), February .

42 ‘Hong Kong Shipping Firms Boycotted: Steamers Tied up at Haiphong: Rice ImportRetarded’, The Hong Kong Telegraph, November .

43 Norway, an independent European state after the dissolution of theSwedish-Norwegian union in , by possessed a merchant marine with the thirdgreatest tonnage in the world, a position that was narrowly maintained for a hundredyears. By , most Norwegian ships calling at Asian ports were steamers inintra-Asian trades, which developed into the most important sector. The most visitedports were Hong Kong, Bangkok, Shanghai, Singapore, and Saigon, all of themsituated on the South China Sea. In , Norwegian steamers were predominantlypresent in Bangkok, where they came second after the German flag. E. von Mende,‘Die wirtschaftlichen und konsulären Beziehungen Norwegens zu China von der Mittedes . Jahrhunderts bis zum . Weltkrieg’, PhD thesis, Universität zu Köln, ,pp. –. Hsiao, China’s Foreign Trade Statistics, pp. –, has the number andtonnage of Norwegian vessels operating in intra-Asian trades from to. S. Tenold, ‘Norwegian Shipping in the Twentieth Century’, in International

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

cut-rate price of cents per rice bag. However, with high demand forrice in Hong Kong, large stocks of rice in Haiphong, and only a smallnumber of steamers available for shipments, it seemed clear toobservers that the boycott would only last for a few weeks.44

Furthermore, with the Chinese employing Norwegian steamers, itbecame obvious that the major Japanese shipping company NipponYusen Kaisha (N.Y.K.) was a powerful competitor in the market. In, entries of Norwegian ships sailing from Southeast Asian portswere registered in the port of Hong Kong, of which were of the fourNorwegian steamers chartered by the N.Y.K.; entries into HongKong were of ships from South Chinese ports. According toP. Tournois, the administrative mayor of Haiphong, in his later reporton the incident, the N.Y.K. had offered to provide the Chinese with allthe tonnage they needed for their exports to China and imports toTonkin; in such a case, the Japanese company may have been inducedto establish itself in Tonkin.45 However, the severe business recessionand strong competition seem to have affected such expansionist plans:the N.Y.K. line from Hong Kong to Bangkok, which had beenlaunched in May , soon faced huge losses due to competition fromthe North German Lloyd. This situation finally resulted in the decisionmade in December to withdraw from the line, bringing about thetemporary end of N.Y.K. activities in Southeast Asia.46

Around the same time, in the first days of December , a jointconference of concerned shipowners and principal rice merchants washeld in Hong Kong, during which both sides tried to find an amicablesolution to the crisis. The Hong Kong Telegraph reported that ‘no definitesettlement could be reached, although it was apparent that there wouldbe no disinclination on the part of owners and shippers alike to meet

Merchant Shipping in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: The Comparative Dimension,L. R. Fischer and E. Lange (eds), International Maritime Economic History Association,St. John’s, Newfoundland, , pp. –; C. Brautaset and S. Tenold, ‘Lost inCalculation? Norwegian Merchant Shipping in Asia, –’, in Maritime History as

Global History, M. Fusaro and A. Polónia (eds), International Maritime EconomicHistory Association, St. John’s, Newfoundland, , pp. , –.

44 The Hong Kong Telegraph, November ; AEAD, Chine, vol. : RenéTeissier-Soulange (in charge of the French Consulate at Hong Kong) to ForeignMinister Stéphen Pichon (Paris), December .

45 National Archives of Overseas Territories [Archives Nationales d’Outre-mer,Aix-en-Provence, France]: ANOM, Gouvernement-Général de l’Indochine (GGI), vol.: Report of Administrative Mayor P. Tournois (Haiphong), October .

46 Wray, Mitsubishi and the N.Y.K., pp. –.

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

each other half way’. With the compromise finally ‘arrived at as the onlypractical solution of the problem in order to remove the deadlock’, thenewspaper announced, the three shipping companies agreed to reversethe price increase, which ended the Chinese boycott of their vessels.Thus, the freight rate on rice was again fixed at cents per rice bag,with business returning to normal in December .47

The first Haiphong shipping boycott of demonstrated that Chineserice shippers reacted sharply to what they regarded as unfair businesspractices. Their reaction certainly became even stronger under thenegative perception of being confronted with the powerful combinationof three shipping companies united in a conference. The boycottseemed to be effective but was short-lived because compelling economicreasons forced Chinese shippers to withdraw their punitive action.However, the lesson from the – incident—the boycotting ofMarty’s ships—was reiterated, namely, that the practice was a strongeconomic weapon when other steam tramps were available for charterand provided alternative shipping options.

The second Haiphong shipping boycott, –

In , the route between Hong Kong, Hoihow, and Haiphong wasfrequently served by six to eight Jebsen, two to three Butterfield, andtwo Marty steamers. The Haiphong port authorities registered

entries of British ships that year, the highest number ever and a clearreflection of Butterfield’s strong position in the market.48 However, aftertheir failed attempt to increase the freight rate, the firms again facedlow profits on the run, especially Butterfield, whose profits were alwaysless than Jebsen’s and sometimes even lower than Marty’s. Confronted

47 ‘Haiphong Shipping Boycott: Probable Compromise: Conference of Owners andShippers’, The Hong Kong Telegraph, December ; AEAD, Chine, vol. :Vice-Consul Joseph Beauvais (Hoihow) to Foreign Minister Stéphen Pichon (Paris), December . French export statistics at the end of show that this year was aturning point after a series of bad harvests and low export numbers in previous years.With , tons of rice shipped from Haiphong, it signalled the beginning of a periodof good—even very good—harvests. The French flag, with calls, again dominatedthe port of Haiphong, with the German flag registering calls. The first appearanceof Butterfield in the market was reflected in ships flying the British flag, compared toa mere vessels the year before. Raffi, ‘Haiphong’, Vol. , pp. , , , .

48 Raffi, ‘Haiphong’, Vol. , pp. , .

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

with such a negative trend, on March , the British firm initiated aconference in Hong Kong with its two rivals, in which it was agreed thatthe freight rate on rice shipped on the Haiphong-Hong Kong run shouldbe increased to cents per rice bag. The decision resulted in an increasein the freight rate of more than per cent.49

Additionally, it was agreed that each of the three firms should put only acertain number of ships on the line to avoid an oversupply of tonnage.The step was obviously directed against Jebsen, who often put a largenumber of ships on the run to secure the lion’s share of the market. Hewas therefore only permitted to regularly employ six ships andoccasionally another two (which the firm used for shipments ofemigrants (‘coolies’) to Dutch East India).50 Butterfield was allowed tohave four ships on the run, and Marty was permitted to employ allthree ships in his fleet and to charter another one if needed. The threeshipping companies were confident that the Chinese rice shippers inHaiphong, whether they liked it or not, would accept the increasedfreight rate when faced with both the coming rich rice harvest of spring and the difficulty of employing alternative steamers for theirrice shipments.51

Such hopes were promptly frustrated. ‘No sooner was this announcedthan the rice exporters in Haiphong began to show their old-timeresentment,’ reported The Hong Kong Telegraph on April . Thepaper even speculated on the motivation of the Chinese merchants:‘Encouraged also, probably, by the success of their campaign, theChinese dealers took up the gauntlet and presented quite as bold afront as they did eighteen months ago.’52 For the new boycott, six largerice trading firms based in Haiphong formed a syndicate or chartercombine and subsequently established the Lien Yi Chinese SteamshipCompany (聯益華輪公司). In Hong Kong the firm initially charteredthree Norwegian steamers on trip charter and the Victoria under the

49 PAAA, Peking II-: Consul Dr Peter Merklinghaus (Pakhoi) to ChancellorBernhard Prince von Bülow (Berlin), April .

50 These Chinese emigrants (‘coolies’) were mostly free migrants leaving voluntarily forDutch East India to work on the tobacco plantations of northern Sumatra. For thedistinction between ‘coolie trading’ and the free emigration of Chinese labourers, seeE. Sinn, Pacific Crossing: California Gold, Chinese Migration, and the Making of Hong Kong,Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong, , pp. –.

51 PAAA, Peking II-: Consul Dr Peter Merklinghaus (Pakhoi) to ChancellorBernhard Prince von Bülow (Berlin), April .

52 ‘Hong Kong Shipping Firms Boycotted: The Haiphong Rice Trade: Grain ImportersFight Shipowners’, The Hong Kong Telegraph, April .

BERT BECKER

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

Swedish flag on time charter for $, per month. The Chinese combinecollected approximately $, from its member firms, which allowed itto offer a cut-rate price of ten cents per rice bag, a considerable decrease(over per cent) of the price fixed by the three European firms.According to information from Jebsen, the minimum price to makesuch shipments profitable was cents per rice bag.53 On April, the journal L’Avenir du Tonkin, after questioning a Chinesemerchant about the case, reported that the current low selling price forrice was one of the reasons for rejecting the increased freight rate.Reporting on the founding of the Chinese combine, called ‘Société duriz’ (Rice Company) in the article, which was charged with charteringsteamers for shipping imports and exports for Chinese merchants inHaiphong, the paper expressed trepidation about the possible negativeconsequences for the French flag should the number of charted vesselsflying the Chinese flag increase in the port of Haiphong.54

The initiator of the Lien Yi Chinese Steamship Company was the majorChinese rice merchant Tam Sec Sam (譚植三), the founder and owner ofthe rice company Shun-Tai (順泰), headquartered in Hong Kong with abranch in Haiphong, as well as the company Chu Ho (聚合) in NamDinh, the Pao Hing Tin Ore Company (寶興錫礦公司) in Mengtze(the Chinese treaty port in Yunnan Province near the border ofTonkin), and the company Pao Hing Tai (寶興泰) in Hong Kong.Tam, who also served as president of the Chinese Chamber ofCommerce in Haiphong, frequently called meetings with other majorlocal Chinese rice merchants to discuss boycotting measures.55

53 PAAA, Peking II-: Consul Dr Peter Merklinghaus (Pakhoi) to ChancellorBernhard Prince von Bülow (Berlin), April ; Consul Dr Ernst Arthur Voretzsch(Hong Kong) to Chancellor Bernhard Prince von Bülow (Berlin), May .

54 ‘Le Boycottage des Chinois’, L’Avenir du Tonkin, April . This newspaper, sold inHanoi and in Haiphong, was the mouthpiece of the French rural settlers (in French: colons)in Indochina, carried ‘racist aspersions on the indigenous peoples, impractical suggestionsdesigned to forward the interests of their readers, and castigations, justified or not, ofmetropolitan and colonial policies and personalities’. J. F. Laffey, ‘Imperialists Divided:The Views of Tonkin’s Colons before ’, Histoire Social/Social History, vol. , no. ,, p. .

55 Tam Sec Sam (譚植三) came from Sunwei, Kwantung Province, in southeasternChina, a mainly agricultural region. Later, relatives brought him to Macao, thePortuguese territory in the Pearl River delta, where he made a living for many years byselling rice and grains. When travelling overseas, Tam also visited Indochina and Siamto study rice production in these regions. He later moved to Haiphong to engage in theTonkin rice trading industry, which provided him with sufficient funds to purchase large

THE HAIPHONG SHIPP ING BOYCOTTS

Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000027Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Hong Kong Libraries, on 10 Oct 2019 at 08:24:24, subject to the Cambridge

On May , after questioning a number of rice merchants, L’Avenirdu Tonkin published a lengthy article on the boycott. According to theinformation obtained by the newspaper, Haiphong’s mayor haddiscussed the matter with the head and the sub-head of one of theChinese congregations, who guaranteed him that the boycott wouldnot happen and that the Chinese charter combine had not obligedVietnamese rice farmers to sell rice exclusively to this syndicate.Nevertheless, the journal urgently called on the government-general toprovide more support to Marty’s shipping company, with strongwarnings that the French flag would be entirely driven out ofIndochina as a result of the current economic struggle of the Chineserice merchants.56

However, despite such fears, from the beginning, three major factorsworked against the Chinese combine in Haiphong. First, at theirmeeting on March in Hong Kong, the three firms had agreedthat if a boycott similar to the one in December occurred, theywould immediately dispatch their ships after unloading at Haiphong sothat they could find other profitable businesses and they would not belaid up at this port. For example, to compensate for the lack of riceshipments, Jebsen instructed his vessels to load other cargo, such as coaland cement, being shipped to Hong Kong and Canton from Haiphongand Hongay (Hon Gay), the site of coal mines on the Tonkin coastoperated by a French-Indochinese firm. They also withdrew ships fromthe run entirely and transferred them to shipping markets in northern