Flooded in Doubt - Columbia Missourian

-

Upload

isabelle-roughol -

Category

News & Politics

-

view

288 -

download

0

Transcript of Flooded in Doubt - Columbia Missourian

C O V E R S T O R Y10A — October 8, 2006 NEWSUNDAY MISSOURIAN NEWSUNDAY MISSOURIAN October 8, 2006 — 11A

Myra Hancock, center, and other members of Columbia’s First Presbyterian Church pray in Luling, La., before their first day of gutting houses.

Missourian staffers Isabelle Roughol, Samantha Clemens and Jenn Jarvis spent a week with a group of Columbia Presbyterians on a cleanup mission a year after Hurricane Katrina. They spent the majority of their time in the Gentilly neighbor-hood, recording the stories of the neighborhood’s residents — in blogs, writings, audio, video and photographs.

South breach: East side of the canal at Mirabeau Avenue, 425 feet wide, occurred at about 9:30 a.m., Aug. 29, 2005.

North breach: West side of the London Avenue Canal at Robert E. Lee Boulevard, 720 feet wide, occurred at about 10:30 a.m., Aug. 29, 2005.

Robert E. Lee Blvd.

Prat

t D

r.

War

ringt

on D

r.

War

ringt

on D

rive

Gentilly neighborhood

Lake Pontchartrain

Mississippi River

New Orleans

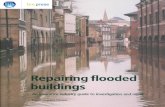

DESTRUCTION’S PATHNew Orleans residents may want to move back, but sometimes it is impossible. Volunteers, often from religious organizations, are still !ltering into the damaged portions of the city. In the Gentilly neighborhood in New Orleans, a few residents who have property on Warrington Drive are !nding they need more help and are

getting it from the volunteers.

Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Missourian reports, Google maps

DUSTY LUTHY/Missourian

Al and Gwen Bierria5286 Warrington Drive

Eddie and Joan Baldo5165 Warrington Drive

Yvonne Birdsall5200 Warrington Drive

Garry and Brenda Hayes4818 Warrington Drive

Mirabeau Ave.

Mirabeau Ave.

Lond

on A

venu

e Can

al

Only one thing had changed in the after-math of Hurricane Katrina: the mud. Dry now, it cracked under the feet of the volun-teers from Columbia’s First Presbyterian Church, who entered 5200 Warrington Drive on a Monday morning in September for the first time since it was flooded.

In the next few days, the house would have to be cleared out, gutted and boarded up. But that did not necessarily mean it would be saved. In April, the city of New Orleans passed an ordinance aimed at reducing the number of derelict, unsafe and unsanitary properties that have been left untouched since the flood. The new law mandated that every damaged house be gutted and boarded up by Aug. 29, 2006, the first anniversary of Hurricane Katrina.

In Gentilly, the streets have been cleared of sand and water, and of the 213 residen-tial lots on Warrington Drive, most have been gutted and secured. The residents, however, have been slow to return. Only 36 families have come back to the neighbor-hood, most of them to live in a government trailer parked in front of their devastated houses. Only one property seems to have been renovated.

The ordinance is also an attempt by city officials to halt the decline of property values for returning residents, many of whom now live near homes that have been abandoned. Property owners must show a good-faith effort toward cleaning or demolishing their houses, or risk losing not

only the structures, but their lots as well. For volunteers like Kathy Montgomery, the outspoken organizer of the Columbia Pres-byterians’ mission trip, the work they’re doing in New Orleans buys time for hom-eowners who do not yet know if they will ever return to Gentilly. But, Montgomery says, the uncertainty is frustrating.

“Are our labors thrown away, dispens-able? Maybe so,” she says. “At least she keeps her property. ... In the ultimate end, we’ve helped her.”

Faith-based groups like the Presbyte-rian Disaster Assistance, the national organization overseeing the work of the Columbia volunteers, have played a huge role in the relief and reconstruction of areas affected by hurricanes Katrina and Rita. This was the third trip to the Gulf Coast by the Columbia group. Many of the volunteers on the recent trip had been there less than a year before, in November 2005. “I was prepared better this time, but it’s still shocking,” Montgomery said. “I was amazed, astounded and very much appalled because there’s been so much of nothing.”

Though they seemed overwhelmed by the devastation, the Columbia group, like all the volunteers who have descended on the city since Katrina, recognize that its work was vital to the future of New Orleans. So after arriving at 5200 War-rington Drive, they grabbed nose masks

Flooded in doubt

More than a year after hurricanes Katrina and Rita ravaged the Gulf Coast, rebuilding drags along while the future of many neighborhoods remains uncertain

CONTINUED on Page 12A

Yvonne Birdsall’s house at 5200 Warrington Drive, in the Gentilly section of New Orleans, hadn’t changed much in the past

year. A moldy stuffed bunny still lies abandoned on the living room floor. Washed-out family photos rested in their broken frames. Plates and cups stood in the dish rack by the sink, dirtier than they had ever been.

HEAR THEIR VOICES, SEE THEIR SIGHTSFor more coverage of the Presbyterians and their trip to New Orleans, see www.columbiamissou-rian.com

HOW WE REPORTED

Story By ISABELLE ROUGHOL ! Photos by SAMANTHA CLEMENS

“It just kills me when I see the kids’ toys,” Columbia volunteer Jodie Burditt said while cleaning a yard in New Orleans’ Gentilly neighborhood. Only 36 families had returned to the area’s 213 residential lots as of September.

! Listen to Isabelle Roughol talk about report-ing from New Orleans.

! Experience the sights and sounds of New Orleans in audio slide-shows and video reports.

! Explore an interactive photo survey of the hurricane-damaged hous-es in the Gentilly neigh-borhood of New Orleans.

! Read the accounts from some of the First Presbyterian Church vol-unteers on www.mymis-sourian.com.

! And in Muse, see the remnants of Edward Bal-do’s home, his memories amid the muck. Page 6C.

wheelbarrows, chased away the wasps that had taken over the residence and started their work.

“They see the need and the purpose,” Mont-gomery said of the rest of the group, “and that’s what it’s all about.”

Yvonne Birdsall, who lived in the house on Warrington Drive in the 1960s before turning it into a rental property, called Presbyterian Disaster Assistance for help in June. She sought the help of volunteers to avoid losing her property under the city’s new ordinance — even though she does not know what the future holds for Gentilly.

“It might have to be demolished, but I’m hop-ing that it can be repaired,” Birdsall said. “If it builds up around here again and people come back, I might end up living back here again.”

When doomsday arrived

Tears well up in Gary Hayes’ eyes when he recalls Katrina’s devasta-tion, which he says reminds him of his time in Vietnam. By the time the storm reached New Orleans on Aug. 29, most of the resi-dents of Warrington Drive had evacuated Gentilly. Gary and his wife, Brenda, a minister, stayed.

She was sitting in her Bible room, pointing a video camera at the hori-zontal rain and the wind tearing at the branches of the trees. He was stand-ing in their front yard. By 9 a.m., the walls of the London Avenue Canal, just west of Warrington Drive, had begun to bend and water was leaking into the neigh-borhood. Gary went inside, grabbed another beer and walked to the end of his driveway to inspect the progress of the water.

“Clear water kept on coming,” he said. “Then I saw this black shadow.”

The shadow — a wall of mud and sand — engulfed Gentilly when floodwall panels on the east side of the London Avenue Canal, about a block from the Hayes’ house, collapsed.

The failure of the floodwall started with a 10- to 20-foot-high “scourhole,” a gap caused by the erosion of the clay and silt that typi-cally covers a levee, in the banks of the canal near the Mirabeau Avenue bridge. As water seeped through the sand beneath the sheet pile that supports the floodwall, the canal started bursting at the seams. The surge of water com-ing from Lake Pontchartrain into the canal increased the pressure on the entire structure, and the clay, silt and sand supporting the flood-wall were pushed away.

The scourhole on the canal side and the loss of material on the land side weakened the levee until the floodwall was standing in equilibrium

with almost no support. Around 9:30 a.m., a 425-foot section collapsed, releasing torrents of water, sand and mud into the Gentilly neigh-borhood.

Two weeks after the storm, only one pump — known even before Katrina as the “dooms-day pump” — was able to start draining the neighborhood.

Al and Gwen Bierria’s house, at 5286 War-rington Drive, is just north of the south breach in the London Avenue Canal. Al likes to speak in metaphors, comparing New Orleans to a beautiful woman who is unkempt and the Corps of Engineers to a drunken driver whose negligence has cost lives. Pessimistic about the state of the city and its future, he is angry at local and federal officials who have not taken

responsibility for what happened and residents who have not made their feelings known.

“The people in New Orleans should be very angry,” he said. “When you have a government agency responsible for a certain task, you don’t have it fall apart. I can understand if a storm would come, and the water would come over the levees. But when you build it and it collapses, that’s a whole other story. ... Negligence and purpose of killing, to me, are the same thing.”

Bierria’s anger is accompanied by fear. He and Gwen are the only residents who have returned to their block of Warrington Drive; they have been living in

a trailer since last October while Al, a contrac-tor, rebuilds their house. He says the Corps of Engineers’ work on the floodwall where it col-lapsed is almost complete. But other sections, including the one just behind his backyard, have not been improved.

“A chain is only as strong as its weakest link,” Al said. “You still have the same chain, the same levee. What’s stopping it from break-ing down here?”

Frederick Young, project manager for the Corps of Engineers in New Orleans’ East Bank, said that the levees that did not fail do not need to be improved because the conditions that contributed to the breach at the Mirabeau Bridge were unique; engineers kept the exist-ing I-panels after finding that there were no other scourholes along the structure.

The breach in the floodwall was repaired to pre-Katrina strength before the start of this year’s hurricane season, and the Corps has continued to improve it. The new section of the floodwall was constructed of T-panels, which add a 3-foot concrete base to the standard I-panel. The T-panel is also supported by three sheet piles instead of one, which go 52 and 74

C O V E R S T O R Y12A — October 8, 2006 NEWSUNDAY MISSOURIAN

CONTINUED from page 11A

Sunday, Sept. 17Our volunteer camp is set up on

the grounds of Luling’s First Union Presbyterian Church. We live in 8-foot-by-6-foot plastic abodes that tend to leak when it rains. In all fairness, we are set up comfortably enough and graciously welcomed. We are only unlucky in one aspect: From what we were told, love bugs only come out in the region two weeks a year for their mating season. It is just the time of year we chose to travel here. Bugs are everywhere. Spray repellent and duct tape are as invaluable as cigarettes in a prison. The volunteers have taped themselves shut in their “villas” to ward off the insects. With thunder rolling in the background, the high humidity and the mosquito nets over our cots, our accommodations resemble a war hospital in a tropical country, except the hospital smell is replaced with that of DEET. No one knows yet what part of the city the group will be working in this week or what the assignment will be.

Monday, Sept. 18The volunteers were given their

assignment at about 8:30 this morning — gutting a house at 5200 Warrington Drive in Gentilly. The mood was light in the van as we were driving to the work site, even when we were stuck in the morn-ing traffic. It was suddenly much quieter, however, when we left the highway and entered Gentilly. We were all staring out of the win-dows, taking in the sights. Broken windows. Piles of debris. Caved-in roofs. Six-foot-high water line.

All houses, with no exception, are spray-painted with the famous X everyone has seen on TV and news-papers. On top of the X is the date the house was inspected — two to three weeks after the storm for most places in the neighborhood. On the right side, there is cryptic code indicating particular hazards inside; in many cases, that was left blank. We know better than to think it means there are no haz-ards. On the left side, the group inspecting the location wrote its initials. At the bottom of the X is the most famous and most morbid indication: the number of corpses found inside. Fortunately, we’ve only seen zeroes so far.

Reporter Isabelle Roughol wrote about her New Orleans experiences on a blog. !e week of writings can be seen at www. columbiamissourian.com.

Kent Hopper, right, and Jo Ann Foriester search for work boots and construction equipment in Luling, La. First Presbyterian Church members from Columbia traveled to New Orleans to gut houses. The volunteers stayed in Luling, about 25 miles from the city, in a makeshift village on a Presbyterian church’s property.

CONTINUED on page 13A

“When you have a government agency responsible

for a certain task, you don’t have it fall apart. I can

understand if a storm would come, and the water would come over the levees. But

when you build it and it collapses, that’s a whole

other story.”AL BIERRIA

New Orleans resident

feet into the ground, instead of the usual 16 feet. When the work is completed, the levee will be covered with plastic to protect it from erosion. However, the Corps of Engineers’ con-fidence in the structure is not matched by that of the residents, many of whom still blame the agency for failing to protect their homes.

‘A wait-and-see game’For others who, like the Bierrias, decide to

return to Gentilly, the journey will be full of obstacles.

“Everything that you’ve got to do is a hassle right now,” Birdsall says. “A big bureaucratic problem.”

The city government’s immediate worry is cleaning up and rebuilding. Many essential city services have been given a lower priority. Recycling pick-up, for instance, has not yet resumed. Instead, there is a special pick-up for “white garbage”: the old appliances and food-filled refrigerators that, 13 months after Katrina, homeowners are just now putting to the curb.

The lack of recycling worries Jo Ann Fories-ter and other Columbia volunteers, who can’t fail to notice that they are adding to the city’s trash problems. The 15 volunteers consumed an average of two bottles of water a day for six days, which contributed about 200 water bottles to New Orleans landfills.

Some people have made the cutback in city services work for them. After traveling around the U.S. and Canada doing construction work for two years, Alberto Mejilla arrived in New Orleans three months ago. He drives around the city and rummages through debris to find semi-precious metals. He said he gets 60 cents a pound for aluminum and 80 cents to a dollar for a pound of copper. While the Columbia vol-unteers worked on Birdsall’s house, he sorted through an enormous pile of wood and drywall and came away with a handful of aluminum bars, probably the remnants of an appliance. Birdsall was glad; at least it wouldn’t end up in a landfill, she said. She then suggested Mejilla look in the backyard for anything else of value.

C O V E R S T O R YNEWSUNDAY MISSOURIAN October 8, 2006 — 13A

Joan Baldo, left, and Kathy Montgomery share a laugh while filling out paperwork to allow Baldo’s house to be gutted and cleaned by the Columbia volunteers.

Tuesday, Sept. 19I saw an old man cry today.

Edward Baldo, 82, was born and raised in Gentilly. In 1952, he bought a lot on Warrington Drive and had a house built for his fam-ily. When the floodwall on the London Avenue Canal collapsed, his home was engulfed in sand and water. Today, the house is wait-ing to be demolished, or sold, but Baldo doesn’t really believe anyone would want his house in its condi-tion. You can knock on every door in this neighborhood, and where there are still residents, you will hear the same stories and see the same sights. I am getting used to this street; its potholes filled with muddy water where we must be careful not to flood our engines; its sidewalks covered with such over-grown vines that it’s safer to walk on the street; its one trailer with the only two residents on the street; and its runaway rooster that hides in abandoned backyards and enter-tains the volunteers. Still, I have to remind myself constantly that we are reporting from the United States of America.

“It’s like a state of limbo, of not knowing exactly how soon this area will develop and how many people will come back,

how many people will build back up.”YVONNE BIRDSALLNew Orleans resident

CONTINUED from page 12A

CONTINUED on page 14A

Edward Baldo’s home was flooded when Hurricane Katrina breached the London Avenue Canal. Today, the house waits to be demolished or sold.

look in the backyard for anything else of value.Since Katrina, Birdsall has lived on her sav-

ings and monthly Social Security check. She received about $20,000 from the Federal Emer-gency Management Agency, but very little from her insurance company because she did not have flood coverage. Her own home, on the other side of the canal from her rental house at 5200 Warrington Drive, was so damaged it had to be demolished. The Corps of Engineers is purchasing an easement on her land to repair another breach in the levee, but the agency has not paid her for the property yet.

The fluctuations in the New Orleans real estate market since Katrina add to the uncer-tainty. Birdsall cannot afford to buy another house: Prices have increased dramatically in areas that weren’t damaged. After the storm, she moved into an $800-a-month apartment that went for $500 before Katrina.

“It’s like a state of limbo, of not knowing exactly how soon this area will develop and how many people will come back, how many people will build back up,” she said. “There’s so many ifs and buts and whys to consider. It’s not a cut-and-dried deal.”

Meanwhile, property values have plummeted in Gentilly and other damaged areas.

“(My) house is worth over $300,000,” Bierria said. “How many people are going to give me $300,000 when they look at this next door and that next door?”

The city of New Orleans has contracted with various architects to plan the rebuilding of the city. In Gentilly, the firm Hewitt-Washington and Associates is responsible for working with neighborhood associations and coming up with a plan that would restore the neighborhood’s

residences, businesses and institutions. Vision-ing meetings have already taken place, but the residents said they were never invited to attend them.

“We don’t get any information, I hate to say it,” Birdsall said. “I think homeowners should be appraised, should get bulletins to keep us abreast with what’s going on, but we don’t get anything.”

To some residents, it seems utopian to think about building parks and restaurants when their most basic needs are still going unmet. They need a place to live and a job. Their neighborhoods are marred by rusty cars, heaps of debris and water pooling into giant potholes on every street.

In the meantime, many homeowners are reluctant to rebuild until they know whether their neighbors will. They can’t afford to pay a construction company to gut and repair their homes, so they turn to volunteers, who see con-tradictions everywhere they go.

“That’s when you begin to run around chas-ing your tail,” Montgomery said, adding that, like the residents, the volunteers are waiting to see what happens.

Presbyterian Disaster Assistance is com-mitted to participating in the relief effort for seven more years, but Montgomery said the organization is having a hard time finding volunteers. Its five villages are only filled to a quarter of their capacity, and the 15 volunteers from Columbia were the only guests in the Luling, La., camp the week of Sept. 18. Mont-gomery, a former village coordinator for the Presbyterians, said the last significant influx of volunteers was last spring, when college stu-

C O V E R S T O R Y14A — October 8, 2006 NEWSUNDAY MISSOURIAN

CONTINUED from page 13A

Wednesday, Sept. 20The Columbia Presbyterians have

worked much faster than anyone anticipated. The 15 “blue angels of hope,” so nicknamed because of the blue T-shirts they wear on the work site, are thanked everywhere they go and greeted by “God bless you” or “We’re so glad you’re here.” Jenn, Samantha and I are often stopped by strangers, too. We are using a KOMU car, and it’s hard to pass by unnoticed when you drive around with a giant, multi-colored peacock on the side of your car. The group had breakfast in Le Café du Monde this morning and had the most deli-cious beignets on this side of the Atlantic. At night, we explored the Quarter’s night life. Kathy Mont-gomery calls it the “give back to the local economy” night. I call it the “blowing off steam mid-week” night. The break was well-deserved. We started with a Cajun dinner, followed by a reasonable amount of the Big Easy’s signature drinks in a live jazz club. We met a zydeco band on the street and were dared to play the washboards with them.

Thursday, Sept. 21Today, I saw Katrina through

the cold eyes of an engineer. Cold probably isn’t the right word for the engineers I met, but the scien-tific explanations I received today from Frederick Young, Corps of Engineers project manager for the reconstruction of levees in Orleans Parish, had the coldness and sever-ity of undeniable scientific facts.

Young also explained to me the work that is being done to repair and better the floodwall where it was breached. I must say, it looks much more effective than the old version, which remains standing in many places, including along the London Avenue Canal behind Yvonne Birdsall’s house. This is what scares the residents of War-rington Drive. Even if the breach is repaired effectively, what’s stop-ping the levee from breaking just 20 yards up the canal, or anywhere else where the old I-panels remain? Young explained to me that the conditions that allowed the flood-wall to breach do not exist along the rest of the canal. Still, the resi-dents are scared, and that might be what prevents many from return-ing.

Bruce Berry, left, and John Montgomery remove destroyed furniture from a house on Warrington Drive in New Orleans. After clearing the house of debris, the 14 Columbia volunteers knocked down moldy walls and ceilings and boarded up the windows of a house damaged more than a year ago during Hurricane Katrina.

CONTINUED on page 15A

Construction continues on the London Avenue Canal levee just one block from Warrington Avenue in New Orleans’ Gentilly neighborhood. Engineers are strengthening portions of the levee that were breached, while other parts remain untouched.

dents on break flocked to the Gulf Coast to do relief work.

The city can’t continue to rely on volunteers alone, she said. Not only are their numbers shrinking, but they cannot do more special-ized work like plumbing and electricity, which requires licensed professionals.

“Will it last seven years?” Montgomery wondered one morning as she sat on a porch on Warrington Drive. “The structures might, but I don’t know that the villages will be filled.People still go to Appalachia, and there’s so much work there. And there will be another hurricane.”

Moving in or moving onThe residents of Warrington Drive are

reminded of the reality of Hurricane Katrina in the most benign and mundane ways. Water-melons started growing in Birdsall’s front yard; floodwaters had displaced seeds, and they grew into odd floral arrangements all over the neighborhood.

Across the street from 5200 Warrington Drive, Joan Baldo now has several clusters of baby’s breath instead of roses. The Columbia volunteers made sure to preserve them when they started gutting her house.

Baldo is an elegant woman who likes to keep a good home and a beautiful garden. She has a sense of humor, although tears come to her eyes when she finds, in the pile of debris in her living room, a favorite black-and-gold beaded gown, which she feigns to model for the volun-teers.

“I’m sorry you had to see my house the way it is,” she said, adding that at least it looks bet-ter now than it did when Warrington Drive was covered in 5 feet of sand. “It looked like beach-front property.”

Joan Baldo has bad knees. So when a new city ordinance required all houses in Gentilly to be raised by 3 feet, she and her husband, Edward, applied for a demolition permit and bought a house in nearby Metairie, which sus-tained significantly less damage.

“It’s sad, but I said I’m over it and I am,” Joan Baldo said. “I really am.”

Others are not so willing to leave. Leroy Smith is an on-site construction specialist for the Corps of Engineers, in charge of build-ing the new floodgates at the entrance of the

London Avenue Canal. He has a personal stake in the project: He lives in Gentilly, too, and he does not want to see his house under five feet of water again. He said he spent so much time working on the canal that he has yet to start work on his own house.

“It still looks like a ghost town in the neigh-borhood,” Smith said. “We got a long way to go, but we can’t give up the fight. We’re not going to let it die. She will not die.”

For all its flaws, residents like Smith take pride in their city. It’s home. Even to those like Bierria, who said “that ‘home’ thing is kind of a cop-out,” New Orleans is hard to turn their backs on, despite its many problems. Bierria mentioned a 2004 quality-of-life poll conducted by the Survey Research Center at the Universi-ty of New Orleans, which found that 40 percent of residents were dissatisfied or very dissatis-fied with their quality of life; that six out of 10 voters thought public elementary education was poor; and that more than one in three thought the city’s problems had gotten worse over the past five years.

“At least Katrina did one thing,” Bierria said. “It got people away from here to see how the rest of the country is doing.”

Today, 13 months after Hurricane Katrina, only half of the city’s prestorm population has returned. Bierria acknowledged the beauty and culture of the city but said that, given better opportunities, anyone would leave, just as they would if Haiti or Cuba were their home.

Yet he remains.“New Orleans is a very, very, very beautiful

woman, and you’ve got a bunch of people that just sling mud in her face,” he said. “It makes you wanna cry, it’s sick. That’s all I gotta say about this place.”

The house at 5200 Warrington Drive had changed by the time the volunteers from Columbia Presbyterian Church left New Orleans on Sept. 23. The evidence of its sad demise had been cleared out and put to the curb, and a bare structure of wood and con-crete stared at a mirror image of itself across the street, and another one and another one again down the road. Each appears naked, except for the X hastily spray-painted on the facade, the only apparent sign that this was once a place called home.

C O V E R S T O R YNEWSUNDAY MISSOURIAN October 8, 2006 — 15A

Friday, Sept. 22Today, we left New Orleans and

drove the Peacock-Mobile — so named by the volunteer team — along the Mississippi Gulf Coast to Pascagoula. The landscape remind-ed us of the scene right after the hurricane in “Forrest Gump,” when the Bubba Gump boat is the only one to have weathered the storm. Apart from the occasional lucky house, everything else was devastat-ed: boats sitting upside down on dry land, cars still in the water, pillars standing with no house on top and an empty shell of a prefabricated home standing on the side of Route 90. Leaving New Orleans was bitter-sweet. We have grown accustomed to the neighborhood we worked in this week and to the small commu-nity of volunteers, homeowners and reporters that we formed on War-rington Drive. However, the week was also exhausting and emotion-ally straining. In the course of my reporting, I heard one phrase a lot: “You can’t understand what it’s like until you’ve been down there.” Now, I understand what all those people meant. As eloquent as one may be, there won’t ever be strong enough words to describe the sights we’ve seen and the stories we’ve heard.

Kent Hopper, left, and Lance Burditt, both of Columbia, board up a house in New Orleans in September. According to the New Orleans’ gutting ordinance, homeowners must properly secure their property or after a series of notices it will be “eligible for expropriation or demolition.”

CONTINUED from page 14A