Fixed Access markets reviews: Call for Inputs

Transcript of Fixed Access markets reviews: Call for Inputs

January 2013 | Frontier Economics i

© Frontier Economics Ltd, London.

Fixed Access markets reviews: Call for

Inputs A REPORT ON OFCOM’S PROPOSALS FOR THE COST

STANDARD TO BE USED FOR LLU AND WLR CHARGE

CONTROLS

January 2013

January 2013 | Frontier Economics i

Contents

Fixed Access markets reviews: Call for

Inputs

Executive Summary 3

1 Anchor pricing 5

1.1 Anchor pricing for other regulated services ................................ 5

1.2 Anchor pricing for the access network with FTTC ...................... 6

1.3 Anchor pricing for FTTP ............................................................. 6

1.4 Conclusion ................................................................................. 7

2 Valuing copper cable 8

2.1 Background ................................................................................ 8

2.2 Assessment of MEA approach ................................................. 10

2.3 Alternative approach to update the value of copper cable ....... 12

3 Common cost recovery 19

3.1 Approach in previous LLU/WLR charge controls ..................... 19

3.2 Common costs under NGA ...................................................... 20

3.3 Common cost recovery with NGA ............................................ 22

3.4 Conclusion ............................................................................... 24

ii Frontier Economics | January 2013

Tables & Figures

Fixed Access markets reviews: Call for

Inputs

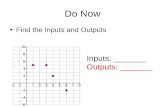

Figure 1. Volatility in Allowable Revenues 14

Figure 2. Normalisation of allowable revenues 15

Figure 3. Projected and actual holding gains 16

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 3

Executive Summary

Executive Summary

Ofcom made three proposals on the cost standard and cost calculation approach

to use when determining the charge control1:

that the ‘anchor’ pricing principle should be used to determine prices

for copper-based access services;

that copper cable should continue to be valued on a Regulatory Asset

Value (“RAV”) basis, rather than attempting to revalue the cable

making adjustments to take account of the fact that copper could no

longer be considered to be the modern equivalent asset (“MEA”); and

that fixed and common costs should be recovered evenly across end

users.

The application of the anchor pricing principle would appear to offer no

demonstrable benefits in terms of consumer welfare. In departing from an

approach based on BT’s actual costs, an anchor pricing approach would be likely

to reduce the accuracy of any cost model and increase uncertainty.

The other two proposals made by Ofcom are an evolution of the approach used

to set the current charge control (which runs from April 2012 to March 2014).

The proposals would allow prices to be set in a robust fashion in a way that is

consistent with the existing charge controls. This would provide certainty for

stakeholders, including end users.

Anchor pricing

Ofcom proposes to implement the ‘anchor pricing’ principle by setting charge

controls on the basis of costs calculated for a hypothetical all copper network.

How such an approach would be implemented is not set out in detail. By their

nature, models of hypothetical networks tend to be more complex and uncertain

than models that reflect actual costs reported by operators. It is not clear what

benefits an anchor pricing approach would bring compared to the approach

based on BT’s actual network and actual costs that Ofcom has used to date.

Copper cable valuation

We agree with Ofcom that applying the MEA principle to existing copper cables

would be complex, requiring a large number of assumptions to be made, with

limited evidence on which to base these assumptions. More importantly, given

that copper cable can be considered non replicable, an approach which attempts

1 Ofcom also set out proposals for implementation of these proposals through cost modelling which

are covered in a separate note.

4 Frontier Economics | January 2013

Executive Summary

to align service costs with that of a hypothetical new entrant would not provide

any clear efficiency benefits.

There would also appear to be little benefit in continuing to update the future

valuation of the copper cable network to take account of movements in copper

prices, which are likely to continue to be volatile. Ofcom could consider using a

more stable price index, such as the RPI, to revalue copper cable assets from

their current regulatory valuation. This would bring benefits by reducing volatility

in wholesale and end user prices, while reducing BT’s exposure to unexpected

holding gains or losses due to unforeseen price movements.

Recovery of fixed and common costs

In the absence of any objective evidence that disproportionately recovering costs

from any given group of customers would provide benefits, Ofcom’s proposals

to continue recovering fixed and common costs broadly equally across customers

appear reasonable.

For Fibre-to-the-Cabinet (“FTTC”) rollout, the methodology can be

implemented by continuing to recover the common costs of the copper access

network2 through MPF and WLR services. For Fibre-to-the-Premises

(“FTTP”), the approach could be implemented by pooling all local access duct

costs, including those specific to FTTP, in the regulatory asset base and

recovering these costs evenly across WLR, MPF and FTTP customers.

This report

The rest of this report covers the above areas in more depth:

the potential use of anchor pricing to set the charge control for copper

based access services;

whether an MEA approach to valuing copper local access assets is

appropriate and whether an alternative approach to updating regulatory

value may better meet Ofcom’s objectives for the charge control; and

the appropriate basis for recovering fixed and common costs of the

access network in the charge control given the NGA roll out.

2 When implementing the cost allocation it is essential that all costs which are incremental to the

NGA roll out (e.g. existing duct refurbishment required to lay fibre) are identified by Ofcom.

Incremental NGA costs should not be recovered from users of the existing copper-based access

services, as this would lead to a clear reduction in allocative efficiency.

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 5

Anchor pricing

1 Anchor pricing

1.1 Anchor pricing for other regulated services

The anchor pricing principle has been previously used by Ofcom for setting

regulated prices where the existing platform is becoming obsolescent, i.e. is not

the MEA. Examples include:

the network charge control covering voice interconnection, where all-IP

networks are used by recent entrants, although BT continues to operate

TDM based voice networks in parallel with next generation equipment;

and

the current leased line charge control where Alternative Interface

Symmetric Broadband Origination (“AISBO”) services based

predominantly on point to point Ethernet services are being replaced by

services which make greater use of shared fibre circuits (such as

Ethernet Backhaul Direct).

In both these cases the new platform is potentially a complete substitute for the

old platform and the new platform has significantly lower long run costs than the

old platform3. Dual running of the old and new platforms is necessary as

switching costs, for customers and for BT, mean that it is not possible to switch

demand instantaneously from one platform to another.

Given this need to run two platforms in parallel, and the existence of fixed costs,

the estimated unit cost of some services could appear to increase, on an

accounting basis, with the introduction of the new platform. This increase can

occur even where the long run cost of the new platform is lower.

One way of looking at this temporary increase in recorded costs is that during the

transition the utilisation of both networks will be lower than their long run

capacity. If this lower utilisation is ignored, this could lead to an increase in

average unit costs. Such an apparent increase in unit costs could be considered to

be simply an inappropriate recovery of costs over the lifetime of assets, not

taking into account lowered utilisation during transition periods. A more efficient

recovery could consist of some combination of: recovering a greater proportion

of the fixed cost of the old platform in the period prior to the transition and;

recovering a greater proportion of the fixed costs of the new platform in the

period after the transition. Such an “economic depreciation” approach would

smooth the profile of unit costs during the transition. However, implementing

economic depreciation approaches typically requires complex calculations, with a

large number of unobservable assumptions.

3 For similar levels of demand

6 Frontier Economics | January 2013

Anchor pricing

Anchor pricing, where prices are projected forward based on the costs of the

existing technology pre-migration, has been used by Ofcom to deal with this

issue. This approach avoids increases in prices and does not require the large

number of assumptions needed to run an economic depreciation approach.

However, an anchor pricing approach could result in BT under- or over-

recovering efficiently incurred costs and will not reflect the costs of the MEA.

1.2 Anchor pricing for the access network with FTTC

The FTTC rollout differs from the two examples above of where anchor pricing

has already been implemented. FTTC has not been implemented as a potential

replacement of the existing platform but rather an overlay to the existing

network. The copper based network will not be withdrawn in the foreseeable

future and will continue to be used to deliver narrowband and broadband

services. The introduction of VDSL through FTTC in this way is similar to the

previous introduction of ADSL on the copper-based TDM network.

Neither the utilisation of the copper network, nor the form of delivery of existing

services, will change with the introduction of the overlay FTTC network. If

properly accounted for, i.e. all incremental costs being recovered from VDSL

services, the FTTC rollout should not increase the costs of services delivered

over the existing network. Indeed, to the extent that the volume of services

delivered over the local access network with the VDSL overlay will be higher

than the hypothetical case where VDSL was not launched, unit copper access

costs could be expected to be lower in the case with a VDSL overlay.

1.3 Anchor pricing for FTTP

BT’s roll out of FTTP is likely to be relatively limited in the forecast period,

covering new housing developments using GPON and a small number of SMEs

with high bandwidth requirements with point-to-point (“P2P”) connections.

The roll out of GPON networks to new developments will be in addition to the

existing copper network rather than a substitute for the copper network, so

again, an anchor pricing approach does not seem necessary4 as there is no period

of dual running.

While the P2P fibre connections may substitute some demand on the copper

access network, it is not clear that the effect of this substitution will be material.

4 However, care will need to be taken when allocating costs to GPON users to ensure that these users

attract a fair share of duct costs common to the existing copper network and the fibre network.

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 7

Anchor pricing

1.4 Conclusion

Ofcom’s reasoning for preferring an anchor price approach is not well explained.

Given the nature of BT’s NGA roll out and Ofcom’s proposed approach on

common cost recovery (analysed later), there seems to be no need to apply the

anchor pricing principle when setting prices for copper based access in the

presence of NGA. Given the approach to common cost recovery, there is no

clear reason why an anchor pricing approach should result in a better outcome

than the existing approach.

In particular, anchor pricing seems to offer no additional protection from higher

prices to consumers compared to the current approach, where economies of

scope should mean regulated prices are, if anything, lower.

An anchor pricing approach would have clear disadvantages in terms of

transparency, being based on a hypothetical network rather than BT’s actual

network. This would make it more difficult to reconcile model results with BT’s

reported costs.

With the current approach there is a risk that costs incremental to the NGA roll

out are misallocated to copper based access services. In theory, an anchor based

pricing approach could provide a check that unit costs are not distorted by such

misallocation5. However, this would require using a “clean” base year for the

copper based services, prior to the roll out of NGA, and the construction of a

forecast model from this point. This would seem to be a resource intensive and

potentially inaccurate approach. Instead, a more robust methodology would

include a focussed inspection of the allocation methodologies used for the latest

base year data in order to check that costs which are incremental to NGA are not

mis-allocated to WLR and MPF. Such an analysis could include comparisons

between areas and over time, to determine whether the roll out of FTTC in an

area resulted in elevated fault rates on existing copper based services, compared

to areas where there was no roll out.

5 Such a check was performed in the process leading up to the setting of the current charge control.

8 Frontier Economics | January 2013

Valuing copper cable

2 Valuing copper cable

2.1 Background

2.1.1 Calculation of allowable revenues

Allocative efficiency is maximised when prices are equal to marginal costs.

However, setting prices at marginal cost would not allow BT to recover the value

of sunk assets, nor fixed costs. For this reason, regulated charges generally are

based upon long run6 incremental costs (“LRIC”) rather than short run marginal

costs. The calculated allowable revenues compensate BT’s investors for all

relevant expenditure as well as the opportunity cost of capital when, as in the

case of investments in fixed assets, there is a delay between the expenditure

incurred and recovery of the expenditure.

Under a historic cost accounting (“HCA”) approach, generally used in in

companies’ statutory accounts, depreciation charges are based on the acquisition

cost of assets, in nominal terms. In this case allowable revenues could be

calculated as the sum of:

a depreciation charge and

the cost of capital employed; calculated as the net asset value multiplied

by a determined cost of capital

The first element allows investors to fully recover the expenditure on the fixed

asset, as a HCA depreciation charge over the lifetime of an asset is equal to the

initial expenditure. The second element compensates investors for the

opportunity cost resulting from the delay between the initial expenditure on the

asset and the corresponding revenues.

2.1.2 Allowable revenues under a CCA approach

Ofcom generally uses current cost accounting (“CCA”) when setting allowable

revenues for fixed assets, where depreciation charges and net asset valuations

take account of price changes. A CCA approach can be based on price changes

reflecting either: changes in general purchasing power, through a general price

inflation or; specific changes in the cost of the underlying assets (replacement

cost). The approach can be implemented either by directly estimating the

appropriate asset valuation or by applying an index to existing valuations and new

acquisitions.

6 Long run in this context means that costs which are variable in the long run, including sunk assets,

are included in the cost calculation.

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 9

Valuing copper cable

Where CCA depreciation reflects the replacement cost of assets, the depreciation

charge can be considered to reflect the expenditure that would be required to

maintain the operating capabilities of the asset base over the period - Operating

Capital Maintenance (“OCM”).

In contrast to HCA, under CCA the sum of depreciation charges over the

lifetime of an asset does not equal the acquisition cost of that asset, due to

changes in its price. As a result, if allowable revenues are set as the sum of

depreciation charges and the allowance for capital employed, investors would be

over- or under-compensated for their initial investment.

In order to allow investors to be full compensated, Ofcom adopts a Financial

Capital Maintenance (“FCM”) approach, where an additional component is

included to the calculation of allowable revenues such that over the lifetime of

the asset investors will fully recover the initial capital expenditure (i.e. financial

capital is maintained). This additional element is the reduction in asset valuation

between the opening and closing of a period that is not accounted for by

depreciation, i.e. any holding loss7.

Where non-FCM approaches are adopted by regulators, for example a pure

OCM approach, where holding gains and losses are not included, the changes in

the regulatory asset valuation will need to be set in such a way that investors are

adequately compensated.

2.1.3 Updating valuations under a CCA approach

As noted above, there are a number of different methods for updating valuations

under a CCA-FCM approach. For example, updated valuations can be based on:

estimates of the replacement cost of existing equipment (a direct

approach);

estimates of the replacement costs of equipment that would be

employed by a new entrant to deliver the same capability as existing

equipment - a modern equivalent asset (MEA) approach;

updating previous valuations based on estimates of specific price

changes in the costs of equipment based on indices (a replacement cost

indexation approach); or

updating previous valuations to take account of changes in general

inflation (a current purchasing power approach).

7 With any holding gain being treated as a negative charge.

10 Frontier Economics | January 2013

Valuing copper cable

Investors should be indifferent to the valuation approach adopted8 as long as

allowable revenues are set consistent with FCM. Different valuation approaches

simply change the timing of when capital expenditure is recovered.

When deciding on the valuation approach, and hence allowable revenues, for

investments in BT’s local access network within the charge control, Ofcom may

take account of a number of criteria to ensure that the charge control:

is consistent with sustainable competition;

calculates charges as robustly, predictably and transparently as possible;

and

provides incentives for productive efficiency by BT.

Below we examine the relevance of these three factors in the context of setting

charge controls for copper-based access prices using an MEA approach.

2.2 Assessment of MEA approach

2.2.1 Rationale for CCA-MEA approaches

For some network assets, other than local access duct and copper cable, Ofcom

has judged that there are potential efficiency gains from aligning allowable

revenues with the cost base of potential new entrant competitors. In order to do

this, assets are revalued based on current equipment costs. Allowable revenues

are calculated with respect to this current valuation rather than the historic

acquisition cost of the assets. This means that competitors’ build or buy decisions

with respect to entry or expansion should reflect whether the competitor has a

lower cost base overall, rather than being potentially driven by changes in the

price of assets over time. Where technological evolution means that entrant

competitors would not install similar assets to those currently operated by BT,

the modern equivalent asset (MEA) principle can be adopted, whereby existing

assets are valued with respect to the modern assets that would be deployed by a

new entrant9.

2.2.2 RAV approach applied to local access cable and duct

For local access duct and cable assets, Ofcom has departed from a pure current

cost FCM approach and instead used a RAV, which values assets purchased prior

to August 1997 at historic cost10 in 2005, indexed from that point based on the

8 In theory, the risk associated with investments, for example the risk of asset stranding, may vary

depending on the approach adopted but the cost of capital used should take this into account.

9 Although in practice the MEA principle appears to be applied infrequently.

10 Assets purchased after August 1997 are valued at net replacement cost.

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 11

Valuing copper cable

Retail Price Index (“RPI”). From 2005 allowable revenues for both pre- and

post-1997 assets are calculated on an FCM basis (i.e. including holding

losses/gains)

The use of RAV reflects Ofcom’s judgement that it is unlikely “that within the near

future any new operator will enter the UK communications industry and build a nationwide

access network able to perform the same function as that owned and operated by BT.”11 In

light of this, Ofcom placed more weight on minimising regulated prices while

ensuring investors were adequately compensated.

The limited potential for competitive entry reflects the fact that the ducts and the

cables that make up local access networks have high fixed costs, which are related

to the number of homes passed rather than the number of homes connected.

These high fixed costs result in high economies of scale which form a barrier to

entry. This means that it is unlikely that there will be significant investment in

the future in competing fixed local access networks12.

This characteristic of fixed local access networks is sometimes referred to as the

networks being ‘non-replicable’ As any investment would effectively duplicate

existing networks and their fixed costs, the potential level of benefits would have

to be very high to justify a more regulatory approach aimed at encouraging

competing access networks. There appears to be little evidence that the potential

benefits due to increases in competition from additional access infrastructure are

of the order of magnitude required to outweigh the productive inefficiency

resulting from duplication of networks. As a result, other factors may be given

greater weight.

2.2.3 Appropriateness of MEA for local access network assets

As access duct and cable may be considered non-replicable, any efficiency gains

from aligning asset valuations with current replacement costs of these assets or

for modern equivalent assets are likely to be minimal. CCA/MEA approaches

would only be appropriate in the absence of any clear advantages of other

approaches.

Ofcom has identified a number of reasons why an MEA approach would be

significantly less robust than continuing with the existing RAV methodology. In

particular:

the calculation of valuations of the network on an MEA basis would

require detailed bottom up cost modelling of a theoretical fibre based

network;

11 Ofcom Valuing copper access: Final statement 18 August 2005, paragraph 1.3

12 While competing cable TV networks were rolled out in the past this was at a time when such

networks had economies of scope which were not available to BT.

12 Frontier Economics | January 2013

Valuing copper cable

it would be difficult to robustly estimate the required abatement to be

applied to the valuation of the copper network to take account of the

increased capability and different operating costs of a fibre based

network; and

moving to a MEA based valuation would introduce a one-off holding

loss13 (or gain) which, unless adjusted for, would not result in the FCM

principle being adhered to.

While the MEA principle, including the potential application of an abatement

adjustment, has been widely discussed in theory, the revaluation of the existing

copper network on an MEA basis raises a large number of practical issues. Any

abatement would need to take account of differences in functionality and

operating costs between copper- and fibre-based networks over their respective

useful lives. Given the limited operating experience of fibre networks with

universal coverage and of the value consumers would place on the additional

functionality provided by fibre, any abatement would be likely to be based on

conjecture rather than hard evidence.

Based on this assessment, we agree with Ofcom that an MEA approach to

valuation is unsuitable.

2.3 Alternative approach to update the value of

copper cable

2.3.1 Rationale for considering alternative approaches

The current RAV approach, which uses a CCA approach for copper cable assets

purchased after August 1997, was selected as there was judged to be a potential

benefit from aligning costs with new entrant in the future, even if in the

foreseeable future significant entry was not thought to be likely. Over time the

allowable revenues under the RAV approach would converge with CCA values

as, pre-1997 assets made up a smaller proportion of the asset base.

Given that Ofcom has considered, but is not proposing, an MEA approach, it is

reasonable to assess whether other valuation methodologies may provide a better

13 It is reasonable to expect that a MEA-based valuation would be lower than a valuation based on

direct replacement cost, once adjusted for differences in capability and operating costs over the full

lifetime of the assets. For a hypothetical FTTP roll out, differences in costs compared to a copper

network could be ascribed to a combination on cost reductions, due to technological progress, and

cost increases due to greater capability – i.e. the ability to offer superfast broadband services. Any

(hypothetical) increase in costs due to additional superfast broadband capability would be recovered

from customers taking the superfast broadband service. Subscribers to services which could be

provided over the existing copper network would thus benefit from any reductions due to increased

efficiency resulting in a lower unit costs.

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 13

Valuing copper cable

match for Ofcom’s objectives. Even if Ofcom were of the view that there were

some benefits from sending appropriate build and buy signals to potential new

entrants, movements in the cost of copper cable would not appear to be relevant,

given that if entry were viable, potential entrants would not choose to install

copper.

Ofcom’s proposal to reject an MEA approach suggests that is judges that the

potential efficiency gains from setting allowable revenues to reflect potential

entrants’ costs are small. In this case other factors may play a greater role in

deciding the appropriate methodology to use to derive allowable revenues in the

future, in particular the implementation of the approach in terms of practicality,

transparency and predictability.

In the remainder of this section we first outline why the current methodology

may not meet Ofcom’s objectives, in particular due to volatility in the underlying

copper price. We then set out an alternative approach, based on indexing the

current RAV based valuation using the RPI, which on balance, appears to more

closely meet Ofcom’s objectives.

2.3.2 Current approach to setting charges for copper cable

Impact of copper price volatility

Ofcom’s current copper cable valuation methodology, used in the charge control,

is based the valuation of BT assets in the RFS. The RFS valuation is based on

the current price of copper cable and an estimate of the volume of copper cable

in BT’s network based on a data drawn from a sample of exchange areas. The

price of copper cable has been volatile in recent years reflecting movements in

the commodity price of copper. This has led to volatility in the valuation.

Allowable revenues, calculated as a combination of the change in value of assets

due to depreciation and valuation changes and a cost of capital, are volatile due

to holding gains/losses from year to year driven by fluctuations in copper prices,

as shown in Figure 1.

14 Frontier Economics | January 2013

Valuing copper cable

Figure 1. Volatility in Allowable Revenues

Source: Frontier analysis of RAV model

The charge control is based on a forecast of allowable revenues. Simply

forecasting forwards from base year allowable revenues would not be

appropriate, because the level of holding gains/losses in that year may differ

from the expected level of holding gains/losses at the end of the period. Ofcom

forecasts allowable revenues in the last year of the price control under the

assumption that copper cable prices are rising at the same rate as RPI in the

forecast period including the final year, i.e. holding gains are normalised. This

normalisation reduces the volatility in allowable revenues, by limiting the

volatility in holding gains/losses, but some volatility remains due to movements

in the valuation of the copper cable network and hence in cost of capital,

depreciation and (normalised) holding gains and losses. This is illustrated in

Figure 2 below.

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 15

Valuing copper cable

Figure 2. Normalisation of allowable revenues

Source: Frontier analysis of RAV model

The resulting volatility in wholesale prices could raise the perceived risk of

downstream competitive entry using regulated wholesale products, thus limiting

the benefits resulting from increased competition. To the extent that volatility in

wholesale prices feeds through into retail prices, this could lead to increases in

churn with customers disconnecting when prices increase and re-connecting

where prices fall, again reducing efficiency.

While setting charge controls based on a forecast of normalised allowable

revenues reduces the volatility of prices, it can also lead to over- or under-

recovery. Due to the volatility in copper prices the outturn holding gain or loss

can be significantly different from the projection underlying the charge control

(as illustrated in Figure 3 below).

16 Frontier Economics | January 2013

Valuing copper cable

Figure 3. Projected and actual holding gains

Source: Frontier analysis of RAV model

To the extent that actual holding gains exceed the projected holding gain, BT will

make a windfall gain, as the increased valuation due to the actual holding gains

will lead to higher depreciation costs at the beginning of the next charge control

will lead to higher prices in future, with no offsetting reduction in charges in the

current charge control due to the additional holding gain. Similarly, if copper

prices fall, BT will suffer a holding loss for which it would not be compensated

through regulated charges. These departures from exact (FCM) cost recovery

may increase the perceived risk for BT’s investors, increasing their required cost

of capital.

Lack of transparency

The current approach to valuation of copper cable purchased after August 1997

is based on BT’s direct CCA valuation that underlies the regulatory financial

statements (“RFS”). This methodology, based on sample data from BT

engineering databases, combined with BT estimates of unit cable costs, is

complex, uncertain and opaque:

a sample approach leads to sampling variation in the results over time;

as it is difficult to accurately measure the quantity of assets in service for

the local access network, estimates of the volume of assets in service,

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 17

Valuing copper cable

required for direct valuation, are subject to a high degree of

approximation; and

direct valuations require making exogenous assumptions about the

assets which are in service, but which are fully depreciated14.

For the current charge control, Ofcom chose to use an indexation approach for

the opening valuation of the local access duct network, rather than using BT’s

direct valuation, in part due to similar issues.

Potential reduction in efficiency incentives

The current methodology couples the forward looking valuation of the total

copper cable network, with the recent prices actually paid by BT to purchase

copper cable. This could reduce the incentives for BT to minimise costs under

the charge control. Any cash cost savings resulting from reducing unit costs paid

for copper cable (for example through increased purchasing efficiency) would be

expected to feed through into the RFS valuation. As a result the short term

benefit due to reduced capital expenditure could be offset by much greater

holding losses at the beginning of the next charge control when the copper cable

asset base was revalued based on the RFS. This mechanism would diminish the

incentives of BT to make such purchasing efficiencies.

2.3.3 An alternative approach: RPI Indexation

In this section we discuss a potential indexation approach for future revaluation

of copper cable assets, based on general inflation such as the RPI. Such an

approach would start with the existing RAV valuation15 as determined for the

current charge control, in order to ensure there were no holding gains or losses

due to the introduction of a new methodology. However, when updating the

valuation of assets purchased post-1997 on a forward-looking basis, both the

opening valuation for successive charge controls and the projection of this initial

valuation to the end of each charge control period would reflect movements in

the RPI, rather than basing the revaluation at the start of each price control on

the results of BT’s direct CCA valuation of copper cables16. The resulting

valuation would not attempt to proxy the net replacement costs of copper cable.

This is similar to the approach used to index the pre-1997 assets from the

determined (HCA) regulatory valuation as at 2005.

14 Whereas, an indexation approach only requires selecting capital expenditure for the relevant period

(i.e. for the last 18 years in the case of copper cable assets).

15 The starting RAV valuation for assets purchased after August 1997 would be based on BT’s direct

valuation, i.e. replacement cost.

16 The use of RPI to index an existing regulatory valuation in the future differs from the use by Ofcom

of the RPI as their best estimate of specific price movements in replacement duct prices for the

period 1997 to 2012 to set the opening RAV.

18 Frontier Economics | January 2013

Valuing copper cable

There are a number of reasons for preferring the use of a general price index

over the current methodology:

Reduced volatility. An indexation approach based on a general price

index would reduce volatility, bringing benefits to all stakeholders.

Wholesale and retail customers would benefit from increased

predictability in prices over time, as they would move in line with

general inflation. BT would benefit by ensuring more accurate cost

recovery, thus lowering its cost of capital17.

Increased transparency. An indexation approach can be implemented

by modifying the existing RAV model spread-sheet, which can be made

available to all stakeholders. The key assumption, the assumed price

index, would also be fully transparent to all stakeholders.

Undistorted incentives. An indexation approach which uses a third

party index, making the revaluation of the asset base exogenous to BT,

ensures that the incentives on BT to increase efficiency due to the

charge control mechanism are effective.

Replacing the current valuation approach with an approach based on updating

the RAV using a general price index would appear to bring benefits to all

stakeholders. The fact that such a valuation would no longer reflect the

replacement cost of copper cable does not seem to be a material disadvantage, as

the local access network is not replicable, and in any case copper cable is no

longer the MEA.

17 Under an FCM approach, BT would still be expected to make a reasonable return on their

investments but there would be reduced variation due to forecast errors in the outturn return.

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 19

Common cost recovery

3 Common cost recovery

Ofcom proposes recovering fixed and common costs associated with local access

networks broadly equally across subscribers, independently of the combination of

access services they take. This is an extension of the current approach.

In this section we:

first discuss the approach adopted in the LLU/WLR charge controls to

date;

discuss the impact of NGA on the cost structure for the local access

network, in particular the degree to which costs are fixed and common

with the existing copper-based network/services;

discuss the potential implementation of an approach similar to that

currently used; and then

draw conclusions on what may be an appropriate recovery of fixed and

common costs.

3.1 Approach in previous LLU/WLR charge controls

To date, Ofcom has set the charge controls by reference to a FAC model. By

allocating all Openreach costs, including fixed costs, between the services

delivered by Openreach, BT should be able to recover a proportionate share of

costs from the sub-set of regulated services. FAC methodologies generally

allocate costs on the basis of causality, that is the costs allocated to a customer or

service should reflect the incremental costs of serving that customer/delivering

that service. Ofcom generally adopts causality when setting regulated prices, but

has departed from strict causality at times where Ofcom judges that there are

benefits from a different cost recovery across services.

As noted above, the nature of fixed local access networks (i.e. duct and cables

between end users and the core network) means that there are high fixed costs.

These fixed costs are effectively common to customers who use the access

network in that they vary little as the number of customers actively connected to

the access network changes18. The costs are also fixed and common across the

services taken by each customer, as they are largely independent of the number

of services that the customer is using.

As a large proportion of the costs are fixed and common, rather than incremental

to a given customer or service, these costs cannot be allocated based on causality

alone. This lack of clear causality when allocating duct and cable costs means

18 The majority of costs are expended in ‘passing’ the premises.

20 Frontier Economics | January 2013

Common cost recovery

other criteria need to be used for deciding on the appropriate cost recovery in an

FAC approach. These criteria could include:

demand side willingness to pay and/or externalities;

dynamic efficiency effects;

not distorting CPs/customers choices between different forms of

service delivery; and

practicality.

Ofcom’s approach in the past has been to allocate the costs of the local access

network broadly equally19 across all users of the copper access network

independently of whether they buy services using MPF, WLR or WLR+SMPF.

This has been implemented by recovering the full cost of the line through WLR

or MPF, with SMPF prices only recovering incremental costs.

By recovering the fixed and common costs broadly equally across all bundles of

services, differences in unit costs should reflect difference in incremental costs

between services. As a result, where a similar package of services is delivered to

end users, operators’ choice of which combination of wholesale services to use

should reflect (incremental) cost minimisation, including any downstream costs.

This should provide incentives for productive efficiency, as CPs will choose the

combination of wholesale products which minimise overall costs.

To date, Ofcom has not taken explicit account of demand side effects such as

willingness to pay, or the potential existence of externalities, when setting access

prices. For example there has been no attempt to allocate more or less cost to

those bundles of wholesale services used to deliver broadband services (MPF or

WLR+SMPF) compared to WLR which is used to deliver narrowband services

alone20.

3.2 Common costs under NGA

BT is rolling out two main forms of fibre based broadband access21:

FTTC to offer VDSL22 broadband services; and

19 The allocation of fixed access costs has differed slightly to take account of differences in line length

and the use of pair gain equipment on some WLR lines.

20 Some account has been taken of dynamic effects, such as the benefits brought by increased

competition, with certain costs being ‘pooled’ and recovered across a range of products.

21 BT is also offering P2P fibre as an option to customers on request. Customers who buy this service

have to pay a distance based charge to connect fibre to their premises in addition to a fixed

connection charge.

22 Very high bit-rate Digital Subscriber Line

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 21

Common cost recovery

FTTP using GPON23 to offer broadband and voice services.

The cost structure, including the costs common to the copper access network

will vary in each case, as detailed below.

3.2.1 FTTC (VDSL)

FTTC is being rolled out by BT as an overlay to the existing copper network.

Wholesale purchasers of the VDSL service are required to purchase either WLR

or MPF service on the same line, in order to provide a narrowband voice line24.

The use of existing spare duct capacity to roll out fibre between the local

exchange and the street cabinet will mean that the costs of the shared duct will be

common across all the services on that route.

The roll out and operation of the FTTC network will lead to a number of costs

which are incremental to FTTC (i.e. would have been avoided if FTTC had not

been rolled out). These incremental costs include:

specific costs, such as the installation of fibre cable and cabinets specific

to the FTTC service and the installation of mini-DSLAMs;

infrastructure costs, such as renovating the duct infrastructure in order

to provide additional duct capacity where there is no spare capacity to

install fibre cables or because the existing duct has collapsed; and

indirect costs, such as the cost of repairing additional faults resulting

from intervention in the access network when rolling out fibre, or

management time related to planning the roll out.

The roll out of FTTC should not affect significantly the (incremental) cost of

delivering MPF or WLR services to those customers who take up the VDSL

service25 as the level of demand and assets and activities used to deliver MPF and

WLR should remain largely unchanged.

There may be issues in accurately identifying all costs which are incremental to

FTTC rollout and operation to ensure these are not recovered from MPF or

WLR. For example, duct installation which is driven by the need to increase duct

capacity to roll out FTTC may be difficult to distinguish from other maintenance

in the duct network. Any mis-allocation of costs from GEA to MPF/WLR will

allow BT to increase MPF/WLR prices, as these are determined by reference to

allocated costs, but will not lead to a direct reduction in GEA prices, as these are

not determined based on the cost allocation. This means that in effect any over-

23 Gigabit Passive Optical Networking

24 Although the end user does not necessarily have to use the narrowband service.

25 Although the fault rate may be elevated due to VDSL being more sensitive to faults than voice, any

increase in fault rates would be incremental to the VDSL service.

22 Frontier Economics | January 2013

Common cost recovery

allocation of cost to MPF/WLR could lead to prices overall being set higher.

Therefore, it is essential that Ofcom makes accurate estimates of these

incremental costs.

3.2.2 FTTP (GPON)

FTTP, using GPON, will be rolled out to new housing developments. No copper

network will be rolled out to these developments as the services that can be

offered over fibre are a super-set of the services that can be offered over copper.

The fibre cables serving such developments may share ducts, and hence common

costs, with the existing copper network, from the optical line termination

(“OLT”) to the boundary of the new development26. The distribution network

within the development is likely to be newly built and, hence, specific to the

GPON network.

3.3 Common cost recovery with NGA

Given the relatively recent introduction of super-fast broadband (“SFBB”)

services, there is likely to be little objective evidence on demand side

characteristics. In the absence of firm evidence showing that a differential

allocation of costs at a wholesale level would result in a more efficient outcome,

an equal allocation of costs across users would appear to be a reasonably neutral

approach. Given the cost structure described above and the roll out of NGA,

the question is how such an approach could be implemented.

In this section we examine how the approach could be implemented under the

two principal NGA technologies.

3.3.1 Implementing common cost recovery on FTTC networks

As an overlay network on top of the existing copper access network, it seems

straightforward and reasonable to extend the existing approach to recovering

costs for ADSL based broadband services. This means that the common cost of

the common local access network would be recovered equally across all

customers, independently of the sets of wholesale services purchased. In addition

to the existing sets of WLR only, WLR+SMPF and MPF, two additional

possibilities are added: WLR+GEA and MPF+GEA.

Under the current product definitions, where all customer lines used for FTTC

need to have MPF or WLR in service, it is reasonable to follow the existing

convention of recovering the fixed and common costs from the WLR or MPF

element of any bundle. To the extent that the roll out of FTTC networks has

26 The cables themselves could potentially be shared with other services such as FTTC or P2P fibre

connections where they share common routes.

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 23

Common cost recovery

required upgrades to infrastructure such as increased duct capacity or new

cabinets, these costs should be separately identified and excluded from costs

recovered from WLR and MPF.

3.3.2 Implementing common cost recovery on FTTP networks

As GPON is not an overlay to the existing copper network, the existing

approach taken for recovering common costs with the introduction of

broadband on the copper network cannot be extended simply to services

delivered over GPON27.

With new build GPON networks, there would appear to be at least three

methods of allocating duct costs, including common duct costs:

pool GPON specific duct expenditure with the existing duct asset base

and allocating these costs evenly across the customers of both GPON

and copper networks;

keep GPON specific new build duct costs separate from the costs of

existing duct network. Allocate the GPON specific costs and a share28

of the costs of the existing network to GPON customers; or

pool duct costs and define an allocation key for duct based on

differential usage of the duct network between copper and GPON

based networks.

The first approach would allocate costs equally across all subscribers, whether

GPON or copper subscribers. It would be relatively straightforward to

implement, by pooling all investment in duct and adding this to the regulatory

asset base. The resulting costs would be recovered across WLR, MPF and

GPON GEA services in proportion to customer numbers.

The second approach would allocate overall costs differentially between GPON

and copper subscribers. Differences in the cost for GPON customers and

copper customers could reflect a range of factors:

new build GPON duct will have a relatively high net asset value

compared to existing duct, as accumulated depreciation as a proportion

of replacement cost will be relatively low;

there will be differences in the terrain/density of new build housing

compared to the existing housing stock; and

27 BT also offers an option for FTTP for customers in FTTC areas ‘on demand’. This option will have

high incremental costs, which should be recovered from users of this service but it would also be

reasonable to recover a proportion of the common duct costs from these customers.

28 Reflecting the use by FTTP of the existing duct network from the OLT to the edge of the new build

network.

24 Frontier Economics | January 2013

Common cost recovery

there may be differences in the relative usage of duct by GPON and

copper networks.

The first two factors will have been applicable to new build (copper) access in the

past. The factors were not taken into account when setting copper based

wholesale prices, which are nationally averaged irrespective of the geography of

the area covered and the age of the network. It is not clear that a differential

recovery of overall duct costs reflecting these differences in cost related to new

build would provide any benefits, compared to an equal recovery of costs

between the two groups of customer.

The third method, a differential allocation which attempts to identify only the

difference between the relative usage of duct by GPON and existing copper

networks, could theoretically lead to some allocative efficiency gains. Any

differences in duct usage would be largely due to different cross-sectional area of

fibre cables rather than route length (as the extent of the route network would

not be expected to significantly change between copper and GPON networks29).

However, the level of incremental cost differences is likely to be small as duct

costs are relatively insensitive to the cross-sectional area of cables.

There are likely to be considerable practical difficulties in measuring/estimating

differential usage of duct network between copper and GPON networks. Given

the limited roll out of GPON in BT’s network, a comparison based on actually

deployed GPON network versus the current copper based network would be

subject to a high degree of sampling error. An approach based on bottom up

modelling of hypothetical GPON and copper networks could be more robust,

but would require significant resources for potentially limited efficiency gain.

Given the likely limited benefits of an approach which attempted to allocate

proportionately more or less duct costs to GPON subscribers, compared to the

practical difficulties of implementing such an approach, it would appear sensible

for this charge control to pool duct costs, allocating them equally across

subscribers (i.e. the first method above).

3.4 Conclusion

Ofcom’s proposed approach, to recover the common costs of the local access

network equally between all customers appears a pragmatic approach, with little

potential loss in efficiency.

In the case of copper cable, this could mean a continuation of the current

approach, recovering all of the costs from MPF and WLR services.

29 Although the topology of GPON and copper networks may differ, the efficient duct network will

generally be a ‘minimum spanning’ tree which connects up all premises in a given area, irrespective

of the cable routing.

January 2013 | Frontier Economics 25

Common cost recovery

In the case of the local access duct network, this would mean pooling the costs

of local access duct in the regulatory asset base, excluding any costs specific to

FTTC, and recovering the resulting aggregate duct costs from MPF, and WLR

services and from FTTP GEA services in proportion to subscriber numbers. The

overlay SMPF and VDSL GEA services would be allocated costs incremental to

the services but not contribute to the recovery of the common costs.

Adopting a neutral approach for this charge control would not prevent Ofcom

moving to a different approach in future charge controls if there was evidence

that an alternative method of recovering common costs would lead to efficiency

gains.

Frontier Economics Limited in Europe is a member of the Frontier Economics network, which

consists of separate companies based in Europe (Brussels, Cologne, London & Madrid) and Australia

(Melbourne & Sydney). The companies are independently owned, and legal commitments entered

into by any one company do not impose any obligations on other companies in the network. All

views expressed in this document are the views of Frontier Economics Limited.