Final Report - UNESCO · Greenall, Mr. Tom Mogeni, Mr. James Humuza, Mr. Néhemie Nkunda Batware,...

Transcript of Final Report - UNESCO · Greenall, Mr. Tom Mogeni, Mr. James Humuza, Mr. Néhemie Nkunda Batware,...

Joint Review Final Report

National Multi-sectoral Strategic Plan on HIV and AIdS 2005-2009

Joint Review Final Report

National Multi-sectoral Strategic Plan on HIV and AIdS 2005-2009

– 4 –

– 5 –

Contents

7 Acknowledgements

9 Executive Summary

13 Acronyms

15 1. Information about the Joint Review

17 2. Methodology of Joint Review

21 3. Joint Review Findings: HIV Service Delivery

65 4. Joint Review Findings: Cross-Cutting Issues

75 Tables

93 References

97 Annex 1: Key questions

109 Annex 2: Districts, Focus Ggroup Discussions, and Other Relevant Activities Conducted in Each District

113 Annex 3: Focus Group Data Collection Tool

117 Annex 4: National Level Key Informants Data Collection Guide

119 Annex 5: District Level Key Informants Interview Guide

121 Annex 6: District Implementers’ Meeting Agenda

– 6 –

– 7 –

ACKnowLeDGeMentS

The National AIDS Control Commission (CNLS) would like to take this occasion to express its deep ap-preciation and sincere thanks to all who participated in this joint review, especially the national and inter-national institutions who contributed technical and financial support including advice, consultation and participation in numerous meetings and workshops. The national partners who deserve special thanks in-clude TRAC Plus, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion, representatives from all national umbrella organizations and district partners.

We would particularly like to thank the members of the Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation Technical Work-ing Group (TWG) who served as the Joint Review Steering Committee and guided the review from devel-opment through implementation. Notably, Ms. Amina Rwakunda, Mr. Gakunzi Sebaziga and Mr. Pierre Dongier from CNLS, Ms. Doris Mukandori from TRAC Plus, Ms. Elisabetta Pegurri from UNAIDS, and Mr. Andrew Koleros from MEASURE Evaluation.

This review was conducted through a team of dedicated international and national consultants who significantly contributed to the development of a comprehensive and participatory methodology and worked tirelessly to ensure high quality data collection, analysis, and concrete recommendations for the development of the new National Strategic Plan. Special thanks go out to our consultant team: Mr. Michel Carael, Mr. Matthew Greenall, Mr. Tom Mogeni, Mr. James Humuza, Mr. Néhemie Nkunda Batware, Mr. Justin Ngendahayo, and Mr. Stanis Ngarukiye.

In addition, a special acknowledgement is due to all na-tional and international stakeholders who participated in the field visits and conducted primary data collection with HIV program beneficiaries. Your dedication to collecting quality data to inform this review is greatly appreciated and facilitated the production of a compre-hensive final report.

— Dr. Anita AsiimweExecutive Secretary, CNLS

– 8 –

– 9 –

eXeCUtive SUMMARY

The joint review of the National Strategic Plan (NSP) on HIV/AIDS 2005-2009 was carried out between August-November 2008. The overall goal of the joint review was to assess progress and achievements of the NSP 2005-2009 as well as to make recommendations to reinforce measures for a sustainable multi-sectoral response to HIV/AIDS across the country.

The review was carried out under the leadership of the CNLS, and it involved stakeholders from all sectors in the collection and the analysis of data. Using routine data, program reports, discussions with program imple-menters and with program beneficiaries themselves, the review examined the following areas:

• Progress in implementing the NSP 2005-2009.• Relevance of the response to the HIV epidemic

and relevance and effectiveness of interventions.• Gaps and areas not adequately addressed, and

solutions to remedy these gaps in the forthcoming plan.

AXiS i: ReinfoRCe MeASUReS of pReventinG Hiv/AiDS tRAnSMiSSionKey achievements and gaps were as follows:

• None of the available data showed strong evidence of increases in HIV prevalence at a national level over the period 2006-2008; however nor do they provide any evidence for decreases in HIV prevalence.

• In terms of behavioral change, data showed both positive and negative changes, with some sources reporting increases in rates of systematic condom use and others indicating an increase in the percentage of young people with more than one sex partner.

• A large proportion of the population was reached by basic HIV/AIDS information and HIV testing.

• Access to condoms, HIV testing, and STI treatment was uneven, with some of the most at risk populations reporting low levels of access.

• On the whole programs failed to systematically target the most at risk groups or the defined “hotspots”. This was partly because understanding of the epidemic has evolved since the NSP 2005-2009 was written, but also probably because of barriers to working in some hard-to-reach or

marginalized contexts.• Different components of HIV prevention are

often implemented in a fragmented way, meaning that many populations are not receiving a comprehensive “package”.

Specific recommendations for HIV prevention efforts the NSP 2009-2012 included the following:

• Ensure that strategies are evidence-based.• Address the causes of stigma.• Provide HIV prevention services and

interventions as a comprehensive “package”.• Ensure continuity of HIV prevention

interventions and services.• Ensure that intensive prevention programs

primarily reach most at risk groups, while continuing to implement broader strategies for the general population.

AXiS ii: nAtionAL ReSponSe to Hiv/AiDS ADApteD to RwAnDA’S ConDitionS AnD SURveiLLAnCe ReSeARCH ReSULtSKey achievements and gaps were as follows:

• Major progress was made in developing new and different data and information dissemination mechanisms and there are several strategies now in place that did not exist in 2005. The two annual research conferences give a national platform for information dissemination and regroup all of the major HIV stakeholders to exchange results, best practices, and lessons learned. However there are still gaps in the routine analysis and dissemination of data.

• The HIV/AIDS Research Committee to assist in the coordination of national and international HIV research was developed during the review period. This mechanism to coordinate research and promote a better exchange among researchers nationally is a large achievement over the course of the plan.

• There is a general lack of strategy for building capacity in research, surveillance and data use, both for technicians and non-technicians.

• There is no mechanism in place to coordinate behavioral surveillance activities being conducted by different actors. In addition, there is no

– 10 –

prioritized list of potential at-risk populations that should be tracked through surveillance.

Specific recommendations for HIV surveillance, re-search and use of data in the NSP 2009-2012 included the following:

• Develop better mechanisms for analyzing data at national level and disseminating them to districts.

• Re-evaluate behavioral surveillance activities given new data and modeling.

• Better coordination of behavioral surveillance activities.

• Review the role of the Research Committee in developing and coordinating a national research agenda with MOH, School of Public Health, TRAC+ and other research partners.

AXiS iii: iMpRove Hiv/AiDS tReAtMent, CARe AnD SUppoRt foR peRSonS infeCteD AnD AffeCteD bY Hiv/AiDSKey achievements and gaps were as follows:

• The proportion of patients in need enrolled into ARV program increased from 35% in 2005 to 76% in 2008. The number of patients lost to follow stayed about constant. Moreover there was significant reduction in the real cost of accessing ARV services by PLWHA with the introduction of Mutuelles de Santé covering for ARV treatment. Opportunistic Infection treatment was included into other services packages offered by community based health insurance. However, a significant gap was that pediatric care was not sufficiently reinforced.

• There was an increase in percentage of facilities offering ARV services from 23% to 43% (Dec 2008); however there was insufficient training for health personnel on existing guidelines in HIV/AIDS care (including pediatric care).

• There was significant improvement in the collaboration between health facility and community based agents to facilitate clients, and community-based care organizations improved HIV/AIDS service delivery compared to the 2005 situation.

Specific recommendations for care and treatment of people living with HIV included the following:

• Harmonize package and monitor the partners to implement national nutritional guidelines, adherence support, and community care and

support.• Adopt task shifting to solve problems of shortage

of human resource.• Develop a strategy to enroll and retain health

personnel in the HIV/AIDS field.• Reinforce pediatric care provision.• Develop guideline and train guidelines users,

particularly for the community based care interventions and for pediatric care.

AXiS iv: MitiGAtinG tHe SoCio-eConoMiC iMpACt DUe to Hiv/AiDSKey achievements and gaps were as follows:

• Income generation activities (IGA) funded through the micro project mechanisms of various projects (MAP, GF, CHAMP, CNLS/UNDP/ADB) have helped a large number of HIV positive member associations to initiate or strengthen collective projects that have had profound effects on their livelihoods, more so in terms of decreased stigmatization and social isolation than in terms of economic status per se. The substantial support to OVCs for access to education is also a major achievement of the last few years and will help to decrease the vulnerability of these children and youths. However, there are gaps in support for management and technical assistance to IGAs, as well as in access to credit.

• Important steps have been made in the establishment of an enabling environment for legal and policy framework for the protection of rights of people living with HIV/AIDS and OVCs and for prevention and prosecution of sexual violence. Access to numerous services for vulnerable groups has also significantly improved during this period: access to health services (Mutuelles de Santé), education, social protection and legal services through various projects. However there are also gaps. There are few workplace programs for HIV prevention and access to care and treatment for employees, lack of coordination of different services (health, social, police, legal assistance) and limited access to legal protection. Identification of OVC at district level has suffered from a lack of transparency and consistent application of criteria, meaning that support does not always reach all of those in need.

• RRP+ has considerably strengthened its coordination mechanisms during the period of the NSP with the setting up of district

– 11 –

coordinators in half of the districts and the strengthening of its central staff for coordination and M&E purposes. The delegation of representation from the grassroots level to the national level ensures the participation of local communities in the planning, implementation and evaluation of activities concerning HIV/AIDS. The transformation of the associations into cooperatives is also a mechanism to ensure fuller participation of members into the decision making process of the organization: well established rules for the functioning of the cooperatives describe clearly the transparency and inclusiveness that must be respected in distribution of profits from the organization’s activities and in decisions about the management of these activities.

Specific recommendations for mitigation of the socio-economic impact of HIV included the following:

• Focus income generation on production activities that respond to the market needs and on cooperatives’ capacity building to identify and assess market opportunities.

• Clarify the regulation on formation of cooperatives in order to ensure that it responds to the vulnerable people’s needs and to support partners in their organizational capacity building and improvement of their business performances.

• Support is required to improve the dissemination of criteria for OVC identification and to increase transparency in how criteria are applied at district level. At the same time, efforts are required to scale up the numbers reached by essential support and to ensure that in each case the minimum

service package is provided. • Understanding of rights is a gap, and emphasis

should be placed on ensuring that vulnerable people know their rights. It is also important to provide legal support and to enhance the collaboration system between health service providers, local authorities and the police.

AXiS v: pLAnninG AnD CooRDinAtion of tHe ReSponSe to Hiv/AiDSSpecific recommendations on planning and coordination:

• Ensure adequate resource allocation for an effective participation of all sectors in the multi sectoral HIV response according to EDPRS, sector strategic plans and annual work plans.

• Strengthening of central structures and especially decentralized structures. Ensure sustainable mechanisms for adequate resources (human and financial) to coordinate and represent civil society organizations.

• Strengthen capacity of CDLS to coordinate all partners within the district and take an active role in fund allocation decision making.

• Develop a national capacity building plan to which all partners will contribute in a coordinated manner.

• Improve involvement of international donors and implementing NGOs in planning and coordination processes. Ensure that international partners’ interventions correspond to priorities identified at national and district level.

• Strengthen regional coordination mechanisms to harmonize cross border aspects of HIV response.

– 12 –

– 13 –

AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency SyndromeANC Antenatal ClinicART Anti Retroviral TherapyBCC/CCC Behavior Change Communication/Communication pour le Changement de

ComportementsBSS Behavioral Surveillance SurveyCAMERWA Centrale d’Achat des Medicaments Essentiels au RwandaCBHI Community Based Health InsuranceCDLS Comité de district de lutte contre le Sida – District AIDS CommitteeCHW Community Health WorkerCNLS Commission nationale de lutte contre le Sida – National AIDS Control CommissionDBS Dry Blood SampleDH District HospitalDHS/RDHS Demographic and Health Survey / Rwanda Demographic and Health SurveyEABC Education, Abstinence, Be faithful and Condom useEDPRS Economic Development and Poverty Reduction StrategyEGPAF Elizabeth Glazer Pediatric AIDS FoundationEPP Estimation and Projection PackageFD Fondation DamienGlobal Fund The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and MalariaHMIS Health Management Information SystemHIV Human Immunodeficiency VirusICAP International Center for AIDS Care and Treatment ProgramsIEC Information, Education, Communication KAP Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice MAP Multi-sectoral AIDS ProgramM&E Monitoring and EvaluationMoH Ministry of HealthNISR National Institute of Statistics of RwandaNLR National Reference LaboratoryNSP National Strategic PlanOI Opportunistic InfectionOVC/OEV Orphans and Vulnerable Children/Orphelins et Enfants VulnérablesPCR Polymerase Chain Reaction (Early pediatric diagnostic technique)PEP Post Exposure ProphylaxisPIH Partners in HealthPIT Provider-Initiated TestingPLWHA People Living with HIV and AIDSPMTCT Prevention of Mother to Child TransmissionPNILT Programme National Integré de Lutte contre la Lèpre et la Tuberculose

ACRonYMS

– 14 –

SE-CNLS Secrétariat Exécutif de la Commission Nationale de Lutte contre le SIDA – Executive Secretariat of the National AIDS Control Commission

STI Sexually Transmitted InfectionSW Sex workerTB TuberculosisTRAC PLUS + Treatment and Research AIDS Center PlusUNAIDS The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDSUPDC Unité de Planification et Developpement des CapacitesUSG United States GovernmentVCT Voluntary Counseling and TestingWFP World Food ProgramWHO World Health Organization

– 15 –

1. infoRMAtion AboUt tHe Joint Review

1.1 – Hiv/AiDS epiDeMiC in RwAnDARwanda has a generalized HIV epidemic, with an HIV prevalence of 3.0% among adults aged 15 to 49 years (4). It is estimated that about 170,000 people, including adults and children, are living with HIV (8). Massive population flows during and after the 1994 genocide have increased the urban population, and there has also been a recent acceleration of urbanization in Rwanda. HIV prevalence rates are higher in urban areas (13% in Kigali City and 5% in other urban areas) than in rural areas (2.2%). Substantial differences in prevalence were also found between men and women (2.3% among men against 3.6% among women) (4).

According to the Rwanda 2008 Epidemic Update, among adults 15+ years old, about 61,500 were in need of ART in 2008, with more than 43,000 (70%) receiv-ing treatment through September 2007. According to Spectrum estimates1, 55% of HIV-positive pregnant women received a prophylaxis regimen through Septem-ber 2007 to reduce the risk of mother-to-child transmis-sion. By December 2008, 75% of health facilities had integrated services for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT), and high levels of women at-tending antenatal clinic visits (ANC) in PMTCT centers were tested for HIV and knew their results. This is esti-mated to represent 66% of all pregnant women in 2008.

1.2 – oveRview of tHe nAtionAL StRAteGiC pLAn (nSp) on Hiv/AiDS 2005-12The National Strategic Plan (NSP) on HIV/AIDS 2005-9 was developed and adopted in 2005. The goal of the strategy was to reduce HIV transmission and alleviate its impact on Rwandese communities, families and people living with HIV/AIDS, and ensure their global care and treatment during the implementa-tion period. The purpose of the NSP is to provide an operational framework through which all interventions against HIV/AIDS find their contribution. The strategy has five main purposes (axes):

1. To reinforce measures of preventing HIV/AIDS transmission.

2. To assure that the national response to HIV/AIDS is adapted to Rwanda’s evolving socio-economic & health conditions by using surveillance and research results.

3. To improve HIV/AIDS-related treatment for persons infected and affected by AIDS.

4. To mitigate the socio-economic impact of HIV/AIDS.

5. To coordinate the Multi-sector response for increased cost-effectiveness.

1.3 – pURpoSe of Joint ReviewThe national HIV response in Rwanda is coordinated by the National AIDS Control Commission (CNLS), following the Three Ones principle. As such, the CNLS is coordinating the development of a new strategic plan for the period 2009-12 in order to align with the Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy (EDPRS) 2008-12. In the EDPRS, HIV/AIDS is mainstreamed as a cross-cutting issue, ensur-ing all sectors define adequate responses to HIV with measurable targets for 2012. As CNLS coordinates the multi-sectoral response to HIV, it is thus necessary that CNLS also harmonizes with the implementation period put forth in the EDPRS. In order to collect a better evidence base for the development of the new plan, the CNLS decided to review the current plan and assess progress to date in achieving the stated objectives. Therefore, data collection on program indicators is a key component of this review as it will feed into the next NSP 2009-2012.

The overall goal of the review is to assess progress and achievements to date in the implementation of the NSP 2005-2009 as well as provide findings and make recommendations to strengthen a sustainable multi-sectoral response to HIV/AIDS across the country. The data presented in this report are only those which are relevant to the review of achievements in the national HIV response during the period 2006-2008. The joint review specifically focuses on the following areas:

• Progress made against planned initiatives: Outputs and Outcomes.

• Relevance and effectiveness of the interventions implemented.

• Gaps/areas not adequately addressed.1. Statistical program used to make estimates and

projections for HIV epidemic in Rwanda

– 16 –

• Constraints facing the national response.• Lessons learnt.• Recommendations for the next NSP.

1.4 – GUiDinG pRinCipLeSThe review used the following guiding principles set forth in the UNAIDS guidance paper Joint reviews of the National AIDS response (2008):

• National Ownership: The review was a national exercise and the process was initiated and driven by the designated national coordinating entity CNLS.

• Relevance: The Joint Review Steering Committee (JRSC) ensured that the design, scope, and any special focus areas for the review were relevant to the status and trends of the HIV epidemic in Rwanda, and of the national response.

• Inclusive and Participatory: All relevant partners and stakeholders were part of the whole process. Particular attention was paid to securing participation of people living with HIV and of most-at-risk populations (sex workers, motorcycle and truck drivers).

• Commitment to results: Involvement in the

planning and implementation of the review also implies that participants agree to follow up on the findings and recommendations.

• Impartiality: The choice of the JRSC as well as the review methodologies were such that it enhanced objectivity and minimized biases and prejudices.

• Evidence Informed: The review was informed by data from national M & E frameworks, complemented by data from partners’ programs or projects, specific sector reviews and reviews of discrete elements of the response. It also took into account and incorporated scientific and technical developments in HIV/AIDS.

• Enhancing national planning: The review was a critical part of programming cycles, and the results will inform the development of the next NSP and future HIV programming.

• Sensitive to gender and human rights: The joint review process provided an opportunity to factor in these important cross-cutting considerations.

• Learning experience: A major consideration and benefit of the joint review process was that it enabled participants to learn from each other’s expertise and experience and contribute to building national capacity.

– 17 –

2. MetHoDoLoGY of Joint Review

2.1 – oRGAnizAtion of tHe Joint ReviewThe joint review was organized according to the M&E plan of the NSP, supplemented by a number of CNLS documents outlining policies and guidance for HIV interventions and outlining key monitoring and evalua-tion indicators. As such, the joint review was organized into four major thematic areas according to the four strategic purposes, or axes, of the NSP: prevention, sur-veillance and research, care and treatment, and impact mitigation.

The last axis of the NSP incorporates general perfor-mance in planning, coordination, and monitoring and evaluation strategies. These strategies were considered to be cross-cutting and relevant to all other thematic areas. Aspects of planning, coordination, and monitoring and evaluation were assessed within each thematic area. In addition, the review extensively used the findings and recommendations from the Country Harmonization and Alignment Tool (CHAT) report to inform the assessment of the last axis. The CHAT exercise cov-ered seventeen public sector institutions, thirteen civil society and private organizations, and ten development partners and assessed the extent of mobilization, partici-pation and inclusiveness in the national response across all stakeholders.

Figure 2.1 displays the overall organization of the joint review. As is described in more detail below, the overall process was guided and led by an Oversight Commit-tee chaired by the Executive Secretary of the CNLS and comprised of high-level HIV stakeholders from all sectors and levels. The technical oversight of the review and the successful implementation of the joint review methodology were managed by a Joint Review Steering Committee (JRSC) chaired by the M&E Officer of the CNLS and comprised of technical staff members from the Planning & Monitoring and Evaluation Technical Working Group (PM&E TWG) on HIV/AIDS.

The JRSC established terms of reference for interna-tional and national consultants to assist with the review. The international consultants were provided by the UNAIDS and World Bank’s AIDS Strategy Action Planning (ASAP) Program and the UNAIDS Regional Technical Support Facility (TSF) for Southern Africa. International consultants assisted the JRSC in the de-

velopment of the joint review methodology, including protocol and data collection tools. International consul-tants assisted the JRSC in the drafting of this report.

Together, the JRSC and international consultants devel-oped four thematic, technical working groups (TWG) according to the four thematic areas and strategic axes of the NSP. TWG members were organized from mem-bers of the Planning & Monitoring and Evaluation Technical Working Group on HIV/AIDS and other HIV stakeholders. The JRSC also recruited a national consultant to chair each technical working group. The JRSC and international consultants were responsible for the data analysis and synthesis, and the production of the final report.

Oversight Committee: An Oversight Committee chaired by the Executive Secretary of CNLS was established to provide national-level advocacy for the overall process of the review and to give guidance to the Joint Review Steering Committee. Other members of the Oversight Committee included the Treatment and Research Center for HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, Malaria and other Infectious Diseases (TRAC Plus) and the Ministry of Health (MOH), the Rwanda Network of People living with HIV/AIDS (RRP+), United Nations institutions (One UN), the Global Fund for AIDS, TB and Malaria (GFATM), and the United States Government (USG).

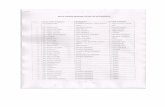

figure 2.1 – organization of Joint Review

– 18 –

In addition, the Oversight Committee was responsible for adopting the final report, and is responsible for ensuring the recommendations of the final report are integrated into the next NSP.

Joint Review Steering Committee (JRSC): In order to as-sure the successful implementation of the joint review, a Joint Review Steering Committee (JRSC) was estab-lished, chaired by the M&E Officer of CNLS and com-posed of members of the Planning &Monitoring and Evaluation Technical Working Group on HIV/AIDS. These members included TRAC Plus and MOH, UN-AIDS, UNDP, UNFPA and MEASURE Evaluation. The JRSC coordinated and managed the overall process of the review, including the following specific tasks:

• Development and management of thematic working groups.

• Adoption of joint review methodology;• Organization of all operations, including field

visits and national-level meetings and workshops.• Routine validation of intermediate results by the

Oversight Committee and other stakeholders.• Production of final consolidated report.• Collaboration with the Oversight Committee to

assure that recommendations will be implemented in the next NSP.

International Consultants: Technical and financial assis-tance for the joint review was provided by the UNAIDS and World Bank’s AIDS Strategy Action Planning (ASAP) Program and the UNAIDS Regional Training and Support Facility (TSF) for Southern Africa through the provision of three international consultants to assist in the review. The ASAP Program provided two prin-ciple consultants to assist the JRSC in the development of the review methodology. Once the final methodol-ogy was adopted, the ASAP consultants also trained the TWGs and related national consultants on the review methodology and provided peer review to intermediate reports produced by the TWGs.

In addition to the support from ASAP, the UNAIDS TSF also provided an international consultant to assist with the HIV Prevention component of the review. As HIV Prevention is a national priority (EDPRS cites re-duction in HIV incidence as one of three major results for the health sector), the JRSC decided that further targeted assistance for the prevention component of the joint review would assist in providing strong, evidence-based recommendations for the development of the next NSP. The international Prevention Expert worked

closely with the prevention TWG and national consul-tant to provide a substantive review of HIV prevention strategies in Rwanda.

Thematic and Technical Working Groups (TWG): For each of the four thematic areas, a thematic and techni-cal working group (TWG) was established to lead the review process. The TWGs were comprised of a wide array of HIV stakeholders at both the national and district level, including public and private institutions, UN organizations, and PEPFAR implementing part-ners. The members of each TWG were from the Plan-ning & Monitoring and Evaluation Technical Working Group on HIV/AIDS.

A national-level consultant was recruited to chair each TWG and ensure the successful implementation of the review methodology. The national consultant was responsible for developing a road map for each TWG, including document review, the adaptation of data col-lection tools, and the identification of all data sources relevant to the thematic area. The national consultants organized all consultative meetings with relevant stake-holders and the TWG and organized the field visits for each thematic area. Each TWG was responsible for providing intermittent reports to the JRSC for overall guidance and validation.

National Level Indicators: The M&E Plan puts forth indicators at each Output and Outcome level of the NSP and defines each indicator, including data sources and responsible agencies. Thus, the indicators for each Outcome and Output were assessed. However some of the Outputs and outcomes of the NSP did not lend themselves to objective assessment. This was largely due to the fact that many of the primary data sources or national-level databases identified in the M&E Plan as data sources were actually not developed, or were not designed to collect the data mentioned in the M&E Plan.

As a result, key questions to guide the review were developed by the thematic working groups. The ques-tions were selected based on an assessment of the NSP Outputs and outcome indicators and the available data sources. Proxy data was used wherever necessary to as-sess the progress made in achieving such Outputs and Outcomes. Overall, the key questions were the basis for analysis of the data/information collected. The Key Questions can be found in Annex A.

– 19 –

2.2 – DAtA CoLLeCtionQuantitative Data Collection: The main sources of quantitative data were the relevant annual reports of the CNLS and TRAC Plus, the principal donor programs (USF, GF and World Bank’s Multi-country AIDS Project (MAP)), as well as the CNLS database and a small number of relevant studies and research indicating progress in relation to the key indicators (e.g. DHS, BSS, ANC surveillance and other studies). These sources provide information on the main strategies that have been employed in the national HIV response, as well as providing some indication of the results of implemented activities.

Qualitative Data: Qualitative data were obtained from studies or evaluations of programs, and were gathered during visits to selected districts, organized within the context of this review. The districts were selected from the four provinces of the country and Kigali city to en-sure that data/information collected was representative of the entire country. Within each province, 2 districts were selected based on urbanization criteria by applying the national categorization of rural and urban districts (i.e. one rural and one urban district was chosen per province). All three districts of Kigali city were selected as well. In total eleven districts were selected, constitut-ing over 30% of the districts in the country. Taking into account these broad principles for representativeness, the precise districts were then purposively selected, with an emphasis being placed on selecting districts where a variety of HIV programs were known to have been implemented during 2006-2008.

These visits to the districts included two principal activities:

• Meetings with the CDLS and key HIV/AIDS program implementers. The purpose of these meetings was to enable district-level actors to contribute to the NSP review by conducting their own appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses of the response to HIV/AIDS in their locality. Implementing organizations were drawn from civil society, private sector and public institutions. One meeting was conducted in each district.

• Focus group discussions with specific target groups. The purpose of focus group discussions was to assess how different target groups react to different interventions, to identify the most and least successful interventions for each group, and to identify gaps in service provision. More than 75 focus group discussions were conducted.

Field visits were conducted by members of the techni-cal working groups set up to coordinate the different components of the NSP review, under the guidance of national consultants and of CNLS staff members. Each of the four teams included members from each of the working groups, meaning that each team had a range of expertise in different aspects of the response to HIV/AIDS. The list of districts, of focus group discus-sions and of other relevant activities conducted in each district is provided in Annex 2.

2.3 – DAtA AnALYSiSFor each Outcome and Output of the NSP and indica-tor in the M&E plan (as well as indicators specified in other sources) data collection tables were prepared specifying the key questions, the likely sources of data for answering those questions, and the methods to be used to obtain data. Data from the different sources were compiled according to these tables in order to pro-vide a national level picture of the main achievements of the HIV response during the review period.

Based on this comprehensive data, overall conclusions were drawn in relation to the main gaps and lessons learned to be taken into account in the future. Primary analysis was carried out by the consultants and resource people leading the review. Over the course of the review the technical working groups, Joint Review Steering Committee and the Oversight Committee provided ad-ditional analytical input.

2.4 – LiMitAtionSIn general, neither the NSP nor the M&E plan includes national targets to be achieved for the various indica-tors. Some targets appear in other documents, but they do not cover the same timeframes and were developed some time after the beginning of the NSP. Annual reports related to the main funding sources (USG, GF or World Bank MAP) occasionally include their own program targets, but aggregating these is not always possible given that they do not all relate to the same in-dicators. The review is therefore limited in its ability to assess whether national HIV response efforts as a whole have over- or under-performed.

It should be noted that program monitoring data from individual implementing organizations were not includ-ed in the review for the most part. This is because of the high risk of double counting, as most implementer figures tend to be included in reports from the major sources already consulted. This means that the review of

– 20 –

quantitative data is essentially macro-level as it is largely based on summary information.

Other important limitations noted include the following:

• For outcome and impact-level data, although the impact data that is available is of a high quality, there is very little data covering the period of the review. The two available national datasets were the 2005 DHS (general population) and the 2006 BSS (specific groups only).

• The main sources of data used for this review do not measure the same indicators in the same way. Hence while some sources emphasize numbers of activities, others emphasize numbers of people

reached by activities.• Program annual reports do not cover equivalent

years as some are based on calendar years and others on fiscal years, making compilation of data by year somewhat inaccurate.

• Overlaps between sources cannot always be identified, so double counting is still a risk.

• Some of the studies used as data sources in this review are questionable in terms of quality of data collected or analysis. Certain figures are presented in this review because it is the only relevant survey that is available and that includes indicators that can be compared to the baselines. However it is essential to keep in mind the numerous caveats around use of these data.

– 21 –

3. Joint Review finDinGS: Hiv SeRviCe DeLiveRY

3.1 – Hiv pRevention: pRoGReSS

3.1.1 – Impact, Outcomes and Outputs under reviewRwanda’s HIV prevention strategy is outlined in Axis I of the NSP, and is further elaborated in the National HIV Prevention Plan (18). The Impact, four Outcomes and fourteen Outputs shown in Table 3.1.1 on page 75 were under review. Indicators for each result level are presented in section 3.1.2.

The National HIV Prevention Plan details the princi-ples and the types of activity to be implemented under most, but not all, of the 14 Outputs in the NSP. The plan also provides strategic and policy guidance, for instance on targeting, on quality control, and on newly introduced approaches to service delivery (such as provider-initiated testing). The plan pays particular at-tention to the organization and coordination of behav-ior change communication (BCC) activities. The plan also lists 15 priority target groups for HIV prevention efforts. Additional national-level documents outlining policies and practical guidance for some of the specific Outcomes and Outputs have also been produced:

• National Strategic Framework on Behavior Change Communication for HIV/AIDS/STI 2005-2009 (May 2004).

• National Operational Guide for Implementation of BCC Programs in Fight Against HIV/AIDS to Priority Target Groups (May 2006).

• National Condom Policy (November 2005).• National Standards and Directives for the

Voluntary Counseling and Testing and Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV/AIDS (January 2008).

3.1.2 – Progress to June 2008Assessing Impact

impact 1 indicator

Reinforce measures for preventing HIV/AIdS transmission

Change in prevalence of HIV/AIdS in people aged 15-24 years

The M&E Plan defines this indicator as the percentage of blood samples voluntarily given by pregnant women

aged 15-24 at ANC clinics which test positive for HIV, citing ANC sentinel surveillance as the primary data source. The plan also cites DHS as a retrospective data source. This indicator is considered to be the closest proxy for HIV incidence in the population aged 15-49. Neither the NSP, the National HIV Prevention Plan, nor the M&E Plan specifies a target to be achieved for this indicator. However, the report on integrating HIV into the Economic Development and Poverty Reduc-tion Strategy in Rwanda 2008-2012 (15) provides a target of 0.5% prevalence among those aged 15-24 by 2012, down from a baseline value of 1.0% in 2005. This baseline value is derived from DHS (4).

All currently available national HIV prevalence data are presented in Table 3.1.2 on page 76. Although the 2005 DHS provides a baseline for this indicator, at the time of writing there are no new comparable data on HIV prevalence rates, so it is not possible to ascertain changes in relation to this measure. On the other hand, HIV sentinel surveillance in antenatal clinics (ANC) provides both baseline values (obtained in 2005) and intermediate values (obtained in 2007).

With the exception of sites in Kigali, all of the ANC results for the different sub-groups shown in the table suggest a slightly higher prevalence in the 2007 study. However, neither the total nor any one of the categories shows an increase that is statistically significant at the 5% level, and the apparent reduction in HIV preva-lence in Kigali is not statistically significant at the 5% level.

Although as noted above, general HIV prevalence among all people aged 15-24 is the official proxy for HIV incidence, the ANC data provide an additional proxy group: HIV prevalence among women who are pregnant for the first time. HIV prevalence is higher in the 2007 sample (3.6%) than in the 2005 sample (2.9%), however the difference between the two is not statistically significant at the 5% level (p=0.059). Indications of relative levels of HIV prevalence between certain population groups can also be inferred from the results of VCT testing. A selection of available data is shown in Table 3.1.3 on page 77.

– 22 –

These data confirm findings of the 2005 DHS and from ANC surveillance that HIV prevalence is considerably higher in Kigali than in other sites, that it is higher in urban locations compared to rural locations, that it is higher in women than men, and that it is higher within the higher age brackets. The data also suggest that pris-oners, female sex workers and truckers are at higher risk for HIV infection.

Assessing Outcomes and Outputsoutcome 1.1 indicators

Change high risk sexual behavior

Change in percentage of 15-24 year-olds reporting sex with non-martial, non-cohabiting partner in the last 12 months (Prevention plan, M&E plan)

Change in percentage of 15-24 year-olds reporting condom use last time they had sex with a non-marital, non co-habiting partner (defined as “high risk sex”) (Prevention plan, M&E plan)

The M&E plan cites the National Behavioral Surveil-lance System at TRAC Plus as the data source for these indicators. Though no formal surveillance system was established during the implementation period, some population-based surveys were carried out over the re-view period. At national level, baseline values for these indicators are provided by the 2005 DHS. As noted previously, the 2006 BSS, which was carried out with young people, sex workers and truck drivers, is also considered as a baseline for this review.

The available data for the two main behavioral indica-tors and for a third indicator (percentage reporting systematic condom use during the past 12 months) are presented in Table 3.1.4 on page 78. The table also shows the DHS (baseline) information for the same indicators in relation to the 15-49 age groups, for information. It should be noted that although the study population for the BSS in 2006 was people aged 15-24, only the data on 15-19 year olds are currently available. The table therefore includes both 15-19 and 15-24 age ranges, to ensure that comparisons are only made for similar population groups.

Table 3.1.5 on page 79 shows all of the national-level baseline data that are available on priority target groups for HIV prevention, for information. It should be not-ed that most of the data sourced from the 2005 DHS in this table is based on very small samples, so they

should not be taken as being representative. It should also be noted that the behavioral indicators collected on sex workers and truck drivers are not the same as the indicators collected for other population groups.

A recently published study by the NGO Mission of Hope provides further indications on HIV prevention behavior of sex workers in three districts: Rubavu, Ru-sizi and Nyaruguru (7). Because the study was limited to three districts, it employed a different sampling strategy to the BSS, and because the same variables were not included in the study questionnaire, it cannot be directly compared to the BSS baseline shown above. In each district, the level to which respondents felt there were obstacles to using condoms with clients were very varied, ranging from 15-71% of respondents. In all three districts sex workers said that clients were pre-pared to pay between 2-4 times more for sex without a condom.

output 1.1.1 indicators

Promote EABC (through IEC for behavior change)

Number of new messages that promote EABC (M&E Plan)

Percentage of people aged 15-24 who know how to prevent HIV transmission (Prevention Plan)

The M&E plan defines this indicator as the number of new or significantly different messages that promote ABC which are disseminated in the year, citing vari-ous intervention agencies as the primary data source. As such a document review of relevant documents was conducted in addition to focus group discussions and key informant interviews.

National policy, strategy and coordination for behavior change programs: Rwanda’s behavior change strategy is based on promoting EABC: Education, Abstinence, Be-ing faithful, and using Condoms. CNLS has produced two key documents to guide the implementation of IEC/behavior change programs: the National Strategic Framework on HIV/AIDS/STI Behavior Change Com-munication 2005-2009 (BCC Strategy) (10) published in May 2004, and the National Operational Guide for targeted BCC Programs (BCC Guide) (14) published in May 2006.

It is important to emphasize that because the BCC Strategy was published in 2004, it is not entirely consistent with the NSP and the National Prevention

– 23 –

Plan, in particular in terms of the list of priority target groups. However, the core principles and processes for designing BCC programs that are outlined in the BCC Strategy remain relevant.

The BCC Guide takes the principles and processes outlined in the BCC Strategy a step further, providing analysis of the specific vulnerability factors character-izing the different priority target groups, defining key behaviors and messages to be promoted for each target group, and providing detailed guidance on how pro-grams for each target group should be implemented. The recommended approach with regard to “ABC” behaviors is to promote each differentially according to the different priority target groups. Accordingly, abstinence and fidelity are promoted for all groups, and condom promotion is generally reserved for groups considered to be high risk.

Implementation of IEC/BCC programs: A range of methods are used to deliver IEC and BCC, including but not limited to community events, mobile video shows, counseling, peer education, radio and television programs, posters and billboards, theatre, songs, docu-mentation centers, printed materials, and a telephone hotline. Many of these methods were used as part of organized thematic campaigns such as the “Global cam-paign” launched by the CNLS and UNICEF in 2005; the campaign on child protection organized by PCFA/Imbuto Foundation and the CNLS in 2006; the Wite-gereza campaign in 2007 aimed at encouraging parents to discuss sexuality, reproductive health and HIV/AIDS with their children (this is further discussed below un-der Output 1.1.3); and the “STOP Cross Generational and Transactional Sex” campaign organized by PSI in 2008. Rwanda also organizes an annual national AIDS day, which takes place during an Umuganda com-munity service day at the end of every year and during which awareness and dialogue on a key issue related to HIV are promoted.

Another major strategy has been the creation of youth anti-AIDS clubs. At the end of 2007 there were over 1,500 functional anti-AIDS clubs, whose main activi-ties are to transmit messages on HIV prevention and responsible sexual behavior to young people and the broader community. There is an apparent decrease in functional Anti-AIDS clubs from 2006 (4,878) to 2007 (1,518). Members of the prevention technical working group suggested that these data can be interpreted in different ways: on the one hand they may imply that

after being set up, many clubs do not continue to orga-nize regular activities; on the other hand it may be that the change in the law requiring associations to become co-operatives has led to many Anti-AIDS clubs being no longer officially recognized. Other informants suggested that the district-level reporting on which the 2007 figures are based may have failed to capture the correct numbers. Overall, existing data about the level of effort for each type of IEC/BCC activity are incomplete.

People trained to deliver IEC/BCC programs and other prevention services: Data on the numbers of people trained to deliver IEC/BCC programs are reported by several sources. Some sources disaggregate data accord-ing to the content of training, whereas others disaggre-gate it according to the profile of those being trained. The range of beneficiaries shows that delivery of IEC/BCC programs is not limited to health facilities, and that they aim to reach people in real life contexts. The summary provided in Table 3.1.6 on page 79 focuses on content, and estimates the proportion of those trained to deliver abstinence and be faithful only (AB only) messages as opposed to those trained to deliver compre-hensive ABC in 2006 and 2007.

As the table shows, in the two years for which complete data is available the proportion trained to deliver AB-only IEC/BCC is between 80-90%. According to the members of the prevention technical working group, this high percentage may indicate that a large propor-tion of IEC/BCC initiatives target young people in schools, as condom promotion tends not to be accepted in schools. The proportion also reflects the priorities of donor agencies, for instance the USG requirement for its programs to prioritize AB-only prevention.

People reached by different prevention methods: As already noted, a range of methods are used to reach people with the aim of changing risky sexual behavior. Table 3.1.7 on page 79 outlines approximate numbers of people reached according to broad categories: the first, outreach, includes peer education, community discussions, Anti-Aids clubs, and events such as mobile video shows. The table does not include people reached by mass-media methods.

Overall the table shows that IEC/BCC programs reach a considerable proportion of the population, and taking into account that data for 2008 is incomplete, it shows that numbers of people reached have been steadily increasing. Unfortunately the available data do not

– 24 –

make it possible to assess what proportion of people are reached by different messages, in particular the balance between messages focusing solely on AB only and mes-sages that include promotion of condom use. Similarly, the data do not provide a detailed picture of how these different interventions are targeted, and the extent to which priority target groups are reached. The narrative sections of the reports cited suggest that the overwhelm-ing focus is on young people, in particular those in school, with the other main target group being the gen-eral population (reached through community events).

In 2007 the CNLS, with the support of UNDP, con-ducted an evaluation of the extent to which the BCC Guide is followed by IEC/BCC programs (13). The main conclusion was that although many of the organi-zations contacted were not aware of its existence or were not actively referring to it in their work, most of them were essentially keeping to the spirit of the BCC Guide. In some cases there was a concern that implementers were not covering all of the proposed messages for each target population. However the biggest challenges that were identified related to funding, planning and moni-toring BCC activities and to ensuring that sufficient materials were available to support BCC programs.Quantitative data on results of IEC/BCC programs: The main source for tracking numbers of new mes-sages is the national BCC committee. According to the annual CNLS activity reports and to the committee itself, 39 new messages or products were approved in 2006, 16 in 2007 and 47 in the first semester of 2008 (20; 22). However, the number and type of new mes-sages, and the extent to which programs follow national policy, are not in themselves adequate indicators of the results of IEC/BCC programs.

The 2005 DHS and 2006 BSS provide national baseline values on HIV-related knowledge that can be disaggregated according to some of the priority target groups. Since no more recent DHS or BSS studies have been conducted at national level there are no compa-rable data which can be used to gauge changes since the baseline in relation to these indicators. All available national data on knowledge are presented in Table 3.1.8 on page 80. The table includes both 15-19 and 15-24 age ranges, to ensure that comparisons are only made for similar population groups.

A recently published study by the NGO Mission of Hope provides an indication of the levels of knowledge on HIV prevention among sex workers (7). As noted

above, the data from this study are not easily com-parable with the BSS data. Nonetheless, like the BSS study the Mission of Hope study suggests that levels of knowledge on HIV among sex workers are generally high, with only a small number of respondents provid-ing incorrect answers. Over 95% of all respondents cit-ed condom use as a means of preventing HIV transmis-sion, with no significant variations between respondents in the three districts. This estimate is a little higher than the value obtained by the BSS (83%).

Qualitative data on results of IEC/BCC programs: The key informant meetings and focus group discussions conducted as part of this review indicated that basic knowledge on HIV/AIDS within the different target groups is generally high. The majority of focus group participants were able to describe how HIV is transmit-ted as well as knowing the main ways of preventing HIV transmission. Focus group participants also cited a range of sources of information on HIV/AIDS, indicat-ing that for the most part people are being reached by BCC messages in a number of different ways.

Most of the sources of information cited were mass communication channels, including radio messages, billboards, and posters; it was less common for par-ticipants to say that they had received information via outreach-type approaches such as community theatre, participatory discussions and peer education, or direct counseling. Although most of the participants had received information from mass communication and outreach sources, a number had also obtained informa-tion from dedicated centers and in health care settings: feedback on the availability of prevention information from Anti-AIDS clubs, and from clinical settings in-cluding youth-friendly centers, was generally good.

On the other hand, in a number of cases focus group participants revealed that there was little continuity to programs throughout the year. It also emerged that very few people had received printed materials on HIV/AIDS, such as leaflets or books. Visits to certain key sites for the delivery of HIV prevention information (such as schools, Anti-AIDS clubs, and “hotspots”) re-vealed that many had run out of materials to distribute to program beneficiaries; none of the “hotspots” visited had any visible information on HIV/AIDS.

In a small number of cases, it emerged that printed ma-terials do not take into account the different languages spoken by Rwandans, or by people travelling through

– 25 –

Rwanda such as long-distance drivers. It also appears that some groups are being reached less effectively by IEC/BCC programs. People who work alone for long periods of time such as long distance drivers and fishermen/women said that they found it hard to get information. There was also evidence that the specific requirements of people with disabilities are not always addressed, making IEC/BCC programs largely inacces-sible to them.

Although responses obtained during the fieldwork indicated that IEC/BCC programs have generally been effective in ensuring that levels of basic knowledge on HIV/AIDS are high, there are indications that the in-formation that is transmitted is somewhat limited. The ability to describe how HIV is transmitted and how to prevent it was seldom matched by more in-depth knowledge on sexuality, sexual and reproductive health, and even on the human body and STIs.

In a number of focus groups, the responses given by participants about how they acted on the informa-tion they had suggested that they did not necessarily have the skills or the ability to understand and act on messages such as abstain, be faithful and use condoms. Hence, participants often said that they believed in or were committed to adopting one of these preventive be-haviors, while their other responses suggested that this may not correspond to their actual behavior but just respond to what they consider as socially desirable. An example of this was a group of boys attending school, who universally stated that they abstained from sex, but later said that they needed better access to condoms.

output 1.1.2 indicators

Increase access to and use of condoms

Number of condoms sold or distributed to end users, broken down by type of user (M&E Plan)

Number of social distribution points for condoms (M&E Plan and Prevention Plan)

The M&E plan defines this indicator as the number of condoms distributed annually to end-users by govern-ment facilities and projects, citing social marketing agency reports collected by CAMERWA and CNLS as the primary data source. Rwanda’s national con-dom policy was published at the end of 2005 (17). The policy positions condoms as a key component of HIV prevention, to be widely promoted in the context

of sexual health and sexuality education. One of the fundamental approaches of the policy is to improve the way condoms are perceived so that they are not stig-matized or loaded with negative connotations, because these connotations constitute obstacles to condom use. The policy therefore calls for multi-sectoral commit-ment to condoms, including support from religious, community and political leaders.

Further evidence of the national commitment to pro-moting condoms and making them available is found in the EDPRS-HIV integration document, which includes measures aimed at making condoms more ac-ceptable as well as including as one of its key indicators an increase in condom use during high risk sex among people aged 15-24 (15). The Prevention Plan also outlines the need for increased condom promotion, and states that condom distribution should increase over the NSP period (18).

Condom promotion and distribution approaches: Dur-ing the period under review, condoms were distributed for free through public sector institutions (generally within the context of workplace HIV programs) and sold through the private sector. The large majority of sold condoms were heavily subsidized and sold under a social marketing brand, Prudence Plus. Female con-doms were distributed through health facilities and tar-geted programs. A recent rapid assessment on condom programming in Rwanda states that there is very little mass media promotion of condoms and that condom distribution within the context of HIV programs is for the most part targeted towards groups considered to be high risk (5).

Quantitative data on condom distribution: Condom distribution is a feature of all the main HIV prevention programs in Rwanda — i.e., the World Bank MAP, Global Fund grants, and USG programs. Table 3.1.9 on page 81 shows the data that are currently available on male condom distribution. The data in the table all relate to male condoms.

The data in the table need to be interpreted with cau-tion. Although the table seems to indicate that numbers of condoms distributed have decreased year from year, this is an incorrect conclusion, as it is clear that data are incomplete, and the figures for 2006 may be inflated (see note to table). However, the table does provide some interesting detail on how condoms are distrib-uted. It shows that condoms are distributed in Rwanda

– 26 –

both via free distribution and through the sale of sub-sidised condoms, and although the sources of data are not specific enough to provide a precise estimation, it suggests that at least half of all condoms distributed are sold via social marketing. Also of interest is the implica-tion that the large majority of free condoms are distrib-uted via the public sector (essentially as a workplace strategy), with very few condoms distributed for free through community or civil society sector partners.

As the table indicates, the data on condoms are very inconsistent between different sources. Overall, current data are very inconsistent between different sources. A calculation of condom consumption is presented in the report of the recent rapid assessment on condom programming (5), see Table 3.1.10 on page 82. This calculation includes condoms distributed under family planning programs, and has been compiled based es-sentially on data from HIV programs.

Data show a modest increase in condom consump-tion overall between 2006 to 2008 (a less than 2% increase), although estimated consumption in 2007 was lower than it was in 2006. Data on the consumption of female condoms are also inconsistent. None of the principal sources for this review provide information on female condoms. The Ministry of Health’s 2006 annual report states that 7,770 were distributed during that year (25), and the 2007 MOH report does not mention female condoms. On the other hand, the rapid situ-ational assessment for condom programming provides a figure of 2,000 female condoms for 2006, 4,200 for 2007 and 5,500 in 2008. In each case, however, it is clear that female condoms do not yet represent a signifi-cant proportion of overall condom use.

Data on condom availability: Condom availability – and the ability of users to access them when needed – is also a crucial consideration. A study carried out on behalf of PSI and the CNLS in 2005 provides baseline data on condom availability (28). The study showed that condoms were available in 93% of urban cellules and in 56% of rural cellules. Nearly three quarters of respon-dents to the survey stated that it was important to be able to access condoms at any time of the day, and there was a significant preference (75%) for obtaining con-doms from small shops and kiosks; the same proportion supported public availability of condoms and an even greater proportion (85%) supported the provision of public information on condoms. And yet, over half of respondents said that they were discouraged from

condom use by the image and reputation that buying condoms might give them, and a significant minority (22%) opposed making condoms publicly available on the grounds that it would encourage casual sex. A large proportion of respondents – over 60% – said that stock outs were an obstacle to consistent condom use. Lack of knowledge of how to use condoms was cited by 54% of respondents as another major barrier to condom use.

The condom availability study does not provide infor-mation on the number of locations where condoms are available, although it does state that they are more likely to be available in shops, kiosks, pharmacies, and health facilities, and less likely to be available in “hotspot” locations such as bars. This is further confirmed by the PLACE study carried out in 2006 (12). National data on the number of condom outlets are incomplete. The condom programming rapid assessment provides some figures on the availability of condoms in public health facilities: in September 2008 only 55 percent of these facilities had condoms. HIV services contacted during the assessment reported that stock-outs and shortages mean that condoms are not always available.

According to the rapid assessment, condom availability is often determined by the authorities in any given situ-ation. Hence, there is no explicit guidance for or against condom provision in school Anti-AIDS clubs, and con-dom availability therefore depends on the school prin-cipal in each case. However, this lack of explicit policy also means that even in cases where the relevant author-ity — for instance a school principal — does want to make condoms available, the supply mechanisms to get condoms to the location are not necessarily in place.

Qualitative data on condom distribution and availability: Data collected during site visits and focus group discus-sions at district level, as part of this review, confirm many of the findings emerging from the 2005 baseline. Knowledge of condoms as a means of HIV prevention was high in all groups, respondents generally had posi-tive attitudes towards condoms, and condom avail-ability was said to be good in urban locations. Good examples of how condoms are accepted included one group of truck drivers saying that they always travelled with condoms, and staff from one bar saying that they included condoms in the price of a beer. People living with HIV also said that they were able to get regular supplies of condoms from health centers. On the other hand, many respondents said that knowledge of how to use condoms correctly was limited. At a societal level,

– 27 –

negative perceptions continue to affect peoples’ will-ingness to use condoms: they are still associated with shame, making people fear that they will be perceived negatively. False information about condoms — for instance that they are dangerous or that their use can interfere with breastfeeding — exist, although they are not common. During one focus group discussion it was stated that parents are responsible for spreading false rumors about condoms in order to discourage their children from using them. On several occasions, imple-menters at district level said that religious organizations actively oppose condoms.

Resistance to condom use appears also to be related to personal preferences. Many people do not like using condoms either because they are not used to them or because they feel that they interfere with sexual plea-sure; men were seen as being particularly reluctant to adopt condom use. In addition, a number of partici-pants said that they were not opposed to condoms as such, but that they felt that the condoms available were of poor quality, and occasionally past their usage date.

Furthermore, for each good example of condom avail-ability, there were several examples of problems. Con-doms are not available in most bars, discos and hotels; many long distance drivers said that they often found it hard to get condoms; and condom availability in rural areas is severely limited. Not surprisingly, condoms are far less easy to come by at night when many people need them the most. An interesting phenomenon which was mentioned several times is that condom prices often go up in the evenings, sometimes to a level that users cannot afford. Stock-outs of condoms seem to occur frequently, and many programs or service pro-viders do not supply condoms — in particular health facilities that are run by religious organizations, but also most of the anti-AIDS clubs. During focus group discussions with prisoners — including prisoners living with HIV — it was confirmed that condoms are not available in Rwandan prisons.

output 1.1.3 indicators

Educate youth on sexual responsibility

Number of schools that receive sex education and/or life-skills curriculum and are trained in its use (M&E Plan)

Increase in the percentage of never-married 15-24 year olds who have never had sex (Prevention Plan)

This Output has some aspects in common with Output 1.1.1 as many of the delivery strategies, such as mass communication campaigns and Anti-Aids clubs, relate to both Outputs. Although the key indicator for this Output in the M&E Plan relates to schools, the strategy also includes out of school youth and education provid-ed by parents to their children. At present it is estimat-ed that 140 schools are implementing programs aimed at providing life skills education to pupils (3). Table 3.1.11 on page 82 summarizes the numbers of teachers trained to deliver life-skills education in schools and the number of school pupils receiving the training.

The half-year figure for 2008 shows that school-based life skills education is reaching a very significant pro-portion of Rwandan schoolchildren; however to date there is no information on the extent to which this education follows established norms.

Quantitative data on programs to educate young people on sexual responsibility: As mentioned above, one report indicates that 140 schools are currently implementing life skills education: this represents 42% of all schools (43). The DHS 2005 provides a baseline value for attitudes of parents towards sexuality education for children — specifically in relation to teaching children about condom use (Table 3.1.12 on page 82).

The baseline value for this indicator shows that a very high proportion of adults (over 80%) states that they support teaching children aged 12-14 about condom use. Data are available on the proportion of young people who have never had sexual intercourse, and are presented in Table 3.1.13 on page 82. Since BSS data for the full 15-24 age range is not yet available, two sets of data are presented: one for 15-19 year olds and one for 15-24 year olds. The UNICEF KAP study data from 2007 are presented with reservations due to meth-odological problems.

The scale of the differences in values obtained by the different sources for people aged 15-19 does not appear to be significant. The findings of the recent UNICEF study for people aged 15-24 do suggest significantly higher levels of sexual activity than was the case for the DHS; however, the UNICEF data should not be seen as evidence for changes since the baseline.

Qualitative data on programs to educate young people on sexual responsibility: The focus group discussions con-ducted as part of this review confirmed that sexuality

– 28 –

education is a feature in many schools. Discussions with young people in school, as well as site visits to a number of secondary schools, showed that HIV education is being integrated into mainstream teaching, and some schools have conducted testing campaigns with support from mobile testing units. However, it emerged that schools do not always have adequate teaching materi-als, and that in many cases teaching is limited to HIV rather than being linked to broader themes related to sexuality and sexual and reproductive health.

The focus group discussions revealed that there are major barriers to dialogue on sexual health and sexu-ality between parents and children. Responses from parents participating in discussions were somewhat varied, with some stating categorically that they did not agree with providing sexual health information to their children, others stating that they were too embar-rassed to discuss these issues with their children and that they felt schools and Anti-AIDS clubs were doing the job sufficiently well, and others still saying that discussing sexual health with their children was their responsibility. Importantly, many of the parents who said they agreed that it was important to discuss with their children admitted that they were not sure how to go about it: they felt that they did not have the knowl-edge or the skills. Although the idea of discussing with their children was accepted, many could not actually go through with it.

Those parents who were the most open about discussing sexual health and HIV prevention with their children appeared to be those who had had in-depth training on HIV prevention: parents who had been trained as peer educators and parents living with HIV stood out as being the most progressive, some of them even stating that they would provide their children with condoms in order to make sure they were protected.

Young people participating in the focus group discus-sions confirmed that for many of them, discussing sexual health and HIV with their parents was impos-sible, and that where it did happen the advice provided by parents was not particularly helpful. Others go as far as saying that condoms are dangerous, in order to discourage their children from having sex. The majority of young people participating in the focus group discus-sions said that they did not dare to talk about these issues with their parents, either through embarrassment or because it would involve admitting to their parents that they were already sexually active.

output 1.1.4 indicator

Increase the number of people in the population that know their HIV/serological status

Number of persons tested who come back to VCT centers for results (M&E Plan)

The M&E plan defines this indicator as the number of persons tested in VCT centers which report to TRAC Plus and return to get their results, citing VCT site monthly summary reports as the primary data source. The National Prevention Plan, revised in 2006, outlines a dual track strategy for HIV testing in the general population: making VCT services available to the entire population and introducing provider initiated testing for HIV in health care facilities. The Prevention Plan also emphasizes the requirement for HIV testing of blood and organ donors.

Measures aligned in the prevention plan to improve testing capacity include not only increasing the number of sites where tests are available, but also improving testing infrastructure to make testing facilities more efficient – for instance by delivering test results more quickly. The Prevention Plan gives particular impor-tance to reach more couples and men with HIV testing. National guidelines on VCT (as well as prevention of mother to child transmission) were published in early 2008. According to the guidelines, the objective of a VCT service is to help the individual to make better decisions concerning his/her sexual behavior and to reduce the risk of HIV transmission.

The document provides detailed guidance and crite-ria for delivering testing both within existing health facilities and in other settings, including mobile test-ing facilities — the guidance covers requirements for infrastructure and equipment, as well as norms for the provision of training to those involved in delivering testing. It emphasizes the requirement for informed consent from people undergoing testing, whether it is carried out as VCT or on the initiative of health care providers (provider initiated testing — PIT).

Scale up of HIV testing has been a major emphasis of the period covered by this review. At the start of the period covered, end 2005, 229 sites were offering test-ing. The Prevention Plan states that the aim by the end of 2009 is to have 400 testing sites with the preferred approach is to integrate testing with existing health facilities rather than setting up stand alone testing

– 29 –

sites. By the end of 2007, 313 sites were offering HIV testing – these include hospitals and public and private community health centers. This is a little higher than the objective of 305 sites that was set for end 2007. By June 2008, 345 sites were offering testing. In addition, the advanced strategy of providing mobile testing has been effectively introduced, meaning that in effect the number of testing sites is even higher. Mobile testing is particularly targeted at most-at-risk populations.

The expansion in numbers of testing sites is mirrored by increases in the numbers of people trained to deliver testing services: for instance, in the first semester of 2008 alone, over 2000 service providers have been trained in HIV testing by Global Fund projects.

Quantitative data on HIV testing: Data on numbers of people receiving HIV testing are centralized by TRAC Plus and are less subject to inconsistencies and double counting between sources. TRAC Plus also reports some targets for the numbers of people to be tested. Table 3.1.14 on page 83 shows the annual targets where available, data on total numbers tested, as well as results for the key indicator for this Output, the proportion of people testing who receive their test results. It also shows numbers tested by mobile testing sites. All data were obtained from TRAC Plus annual reports unless otherwise noted.

As the table shows, there is a steady progression in the numbers of people being tested for HIV, and the numbers tested per year represent a significant pro-portion of the Rwandan population. If testing rates continue at their current pace it looks likely that a test will have been administered for more than one in every ten Rwandans over the course of 2008. This does not mean that 10% of Rwandans take an HIV test each year because some people may have tested more than once. However this level of testing suggests that the percentage of “ever-tested” Rwandans is likely to be higher than the levels measured during the DHS survey in 2005, when 23.4% of respondents had ever had an HIV test.

Where data are available (2007 and 2008), the percent-age of people receiving counseling who then agree to take an HIV test is very high (>99%). The targets for numbers to be tested set by TRAC Plus for 2006 and 2007 were met and surpassed, and mid year figures for 2008 indicate that the number of people being tested is still increasing. Data on the percentage of people tested

who receive post-test counseling were not found in any of the source documents. However, the percentage of people receiving their test results – 97% in 2007 – is also encouraging, as the DHS survey had indicated that in 2005 fewer than 90% of people receiving testing had also received their results. However, the half-yearly results for 2008 show that the percentage receiving their results has dropped to 94%. The percentage of mobile testing clients receiving their results is not reported, although there are anecdotal reports that the percentage is lower than for fixed testing sites.

As noted above, as well as increasing the numbers of people tested, the advanced mobile VCT strategy is designed to reach most-at-risk populations. As the data in the table for 2007 show, in contrast to facility-based testing, more men than women are tested via mobile VCT. This is likely to be related to the fact that mobile VCT efforts have targeted predominantly male groups such as prisoners and soldiers (over 7,000 individuals in each category were tested through mobile VCT in 2006). The availability of testing facilities in prisons has improved significantly in 2008, with at least 8 prisons introducing testing since the beginning of the year (30). In these 8 sites, nearly 14% of prisoners have had an HIV test.