FEATURE Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox · PDF file12 ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1....

Transcript of FEATURE Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox · PDF file12 ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1....

10 ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1. APRIL 2000

F E A T U R E

Strong community support

led to government protection

of a bat colony in northern

Sydney in 1985. Restoration

of the roosting habitat of the

Grey-headed Flying-fox

(Pteropus poliocephalus)

was implemented by a non-

government organization in

cooperation with the local

government. The aims,

methods, results and

challenges of the project so

far are outlined.

Acolony of Grey-headed Flying-foxes(Pteropus poliocephalus) roosts in urban

bushland in the northern Sydney suburb ofGordon (13.5 km north of the central busi-ness district). Environment groups becameaware of its location following a survey ofbushland in the Ku-ring-gai Local Govern-ment Area (Buchanan 1983). Part of the landoccupied by the flying-foxes was privatelyowned and a proposal to develop this forhousing led to strong lobbying by the com-munity for protection of the bat colony.The NSW Government and Ku-ring-gaiMunicipal Council jointly purchased theprivate land in 1985.This land was amalga-mated with Council-owned bushland andnamed Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox Reserve(14.6 ha) in 1991.

The Ku-ring-gai Bat Colony Committee,now the Ku-ring-gai Bat ConservationSociety Inc. (KBCS), formed in 1985, recog-nized a longer term threat to the flying-foxcolony. Serious die-back of the canopy treesused by the roosting flying-foxes was occur-ring and severe weed infestation of theunderstorey was preventing regeneration ofnew trees. A site assessment commissionedby KBCS stated: ‘The native vegetation isdying and will be replaced within the next15–30 years by a tall shrub layer consistingof Lantana (Lantana camara), Small-leavedPrivet (Ligustrum sinense), Large-leavedPrivet (Ligustrum lucidum) and one nativespecies, Pittosporum (Pittosporum undula-tum). Morning Glory (Ipomoea indica) and‘Trad’ (Wandering Jew; Trad fluminensis)will also remain very common. The trees,Blackbutt (Eucalyptus pilularis), Turpen-tine (Syncarpia glomulifera), Sydney RedGum (Angophora costata) and RedMahogany (Eucalyptus resinifera) will nolonger be present (Buchanan 1985)’.

Loss of this habitat could result in flying-foxes moving to an unknown, next-best sitein the Sydney area with the potential for

conflict between people and bats. As ittakes decades for trees to grow to a sizecapable of withstanding flying-foxes roost-ing in their canopy, immediate interventionappeared to be the best course of action.

Flying-foxes at Gordon

Flying-foxes were seen to rise out of thevalley east of Gordon in the 1940s (H.George, pers. comm., 1983). From 1963, thegardener of a neighbouring property, LadyGowrie Nursing Home, noticed flying-foxescamped each summer along Stoney Creekand on the steep, north-facing slope in whatis now the western section of the Reserve.Breeding was observed and the colony num-bered approximately 2000 in 1973 (Robin-son 1973).The colony occupied between 1and 2 ha and began occupying the sitethroughout the year (Puddicombe 1981).Regular counts during the nightly exodusfrom the valley, from March 1985 to June1990, fluctuated from a few hundred to onepeak of 80 000 in February 1987 (Parry-Jones 1993). Counts between December1994 and November 1997 again showedfluctuations between zero and 59 000(D. Ford & M. Augee, pers. comm., 1998).Monthly counts from July 1998 to June 1999recorded a winter population of 13 000,rising to 45 000 in summer (M. Beck, pers.comm., 1999).

The colony has occupied an area of 2–3 ha, with variations according to fluctua-tions in the numbers in residence at anyparticular time. Since the early 1980s therehas been a gradual shift eastward of thecolony from the western end of the Reserveto the present position in the centralsection (Fig. 1), and it appears that theflying-foxes prefer to camp on slopes with anortherly aspect, especially in winter. Infor-mation gathered by KBCS on other flying-fox colonies at Wingham Brush, Bellingen

Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox ReserveHabitat restoration project, 15 years on

By Nancy Pallin

Nancy Pallin is a founding member of the Ku-ring-

gai Bat Conservation Society Inc, PO Box 607,

Gordon NSW 2072, Australia. This article is based

on her experience coordinating the Habit Restora-

tion Project and the volunteer bush regeneration

team at Flying-fox Reserve over the last 15 years.

Island, Susan Island, Maclean, Booyong, Jam-beroo and Indooroopilly Island confirmedthat they occupy different parts of the avail-able habitat over time.While the reasons forsuch shifts are not known, such movementswould allow recovery of the tree canopy,given that defoliation of branches occurs atregularly used roosts.

Flying-fox colonies occur in many differ-ent vegetation types including rainforest,casuarinas, mangroves and in native andexotic trees in the Botanic Gardens inSydney and Melbourne.This would suggestthat the structure of the vegetation is moreimportant than species of tree.The Gordonbat colony site assessment identified thatflying-foxes use vegetation consisting offour layers (Buchanan 1985).They used thetallest trees, Blackbutts and angophoras, towarm themselves on cool early morningsand to cool themselves in summer breezes.The most commonly used layer was the(somewhat lower) Turpentine canopy, withtaller shrubs used in high temperatures oron cold, windy days. In extreme heat(greater than 40°C) with dry westerly

winds, a local resident had observed bats onthe ground and clinging to rock faces whereseepages occurred.

Aims of the project

The primary aim of the habitat restorationproject was to provide self-perpetuatingindigenous roosting habitat for the colonyof Grey-headed Flying-foxes. A secondaryaim was to retain the diversity of nativefauna and flora within the Reserve.A furtherissue was that the regenerated vegetationshould be compatible with native bushlandin northern Sydney.

Habitat restoration start

Habitat restoration work focused on bush-land weed control, initially undertaken by asmall group of volunteers. Four hours perweek, four to 10 ‘friends of bats’, some expe-rienced in techniques of bush regenerationpractised in other parts of Sydney, girdedtheir loins with the uniform tool pouch,loppers and herbicide bottle (glyphosate).

ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1. APRIL 2000 11

F E A T U R E

They began the seemingly impossible taskof implementing a weed control strategybased on releasing all areas with naturalregeneration capacity from suppression byweed (Buchanan 1985;Wright 1991).

Phase 1 : 1987–90

The work of the volunteer team was latersupplemented by a contract team, whoseemployment was made possible by a seriesof grants gained by the KBCS from the NSWDepartment of Environment and Planning.These grants were matched dollar for dollarby the Ku-ring-gai Municipal Council. Thecontract team worked in separate areasfrom the volunteers using the same tech-niques (Buchanan 1990). In the first year, athree-person contract team worked 5 daysper week for 3 months to undertake addi-tional weed control works on steeperslopes. Subsequently, this work was ex-tended over the year, by contractorsworking 1 day per week for approximately40 weeks. This enabled time for regenera-tion to occur and follow-up weeding to becarried out regularly over all areas.

Phase 2 : 1992–97

By 1990,the flying-fox camp had moved east-wards in the valley.This, and a NSW Restora-tion and Rehabilitation Trust Grant, allowedthe contract team to undertake restorationof the very degraded western section thatwas previously inhabited by the bats.

Phase 3 : 1998–2000

A Natural Heritage Trust (CommonwealthGovernment) grant enabled contract bushregenerators to be employed to establishcanopy seedlings in a 0.25-ha area withinthe colony site. This area had only a fewTurpentines and Blackbutts left for roosting.Regenerators were also able to preventfurther degradation of moderately weed-infested bushland on the northern andsouthern upper slopes by comprehensiveweed control undertaken outside thecolony area.

A mosaic of treatmentsThe reserve contains a mosaic of habitatsranging from rainforest in the riparian zonesand lower slopes and sclerophyll habitats onupper slopes. This means that a range of

Figure 1. Three ‘snapshots’ showing the progressive movement of the flying-fox colony overtime. Records are available from 1972.

12 ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1. APRIL 2000

F E A T U R E

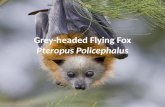

Grey-headed Flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) and Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox Reserve

A Grey-headed Flying-fox licking nectar and pollen from a Turpentine flower (photo: D. Williams).

In 1984, NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) identified the bat colony as ‘the largest and most important mater-

nity colony of the Grey-headed fruit bat known in the southern half of New South Wales. As such, it is probably crucial to the

future survival of this species in the southern half of the State (McWilliam 1984)’. Since then, radio-telemetry research on the

Grey-headed Flying-fox has provided new perspectives on the nomadic foraging behaviour of the species. Colony sites, such as

the one at Gordon, are viewed as essential links in a chain of sites which are used permanently, annually or occasionally accord-

ing to the availability of food resources (Eby 1995). These social mammals roost in trees by day. Colonies vary considerably in

size from hundreds to many thousands, fluctuating according to variations in food resources (Parry-Jones & Augee 1991; Tide-

mann 1995; Eby 1996; Stockard 1996).

Their diet in Australia contains more than 100 species of native trees found in subtropical rainforests, eucalypt forests and

woodlands, melaleuca swamps and banksia heaths (Parry-Jones & Augee 1991; Eby 1996). They undertake nomadic movements

of hundreds of kilometres in response to unpredictable mass-flowering events in sclerophyll forests (Eby 1991b, 1995, 1996).

Large populations of flying-foxes are considered essential to the ongoing ecological functions of seed dispersal and pollination

in both rainforest and sclerophyll forests (Eby 1996). They are known to disperse the seeds of at least 40 Australian rainforest

trees (including figs, palms and lilly pillies) and are pollen vectors for more than 50 species in the Myrtaceae and Proteaceae

(Parry-Jones & Augee 1991; Eby 1995).

Females give birth, annually, to one young in October–November. The infant is carried ventrally by the mother on her noctur-

nal foraging flights in the first weeks until it can regulate its body temperature. It is then left at the roost overnight, the mother

returning by dawn to nurse it during the day until the young learns to fly and feed independently, at approximately 3 months of

age. Conception occurs from March to May. Flying-foxes use scent from glands on their shoulders to attract mates and identify

young. Females call to their young as they fly into the colony before dawn in early summer. They communicate by using more

than 20 different calls (Tidemann 1995).

In the Action Plan for Australian Bats (Duncan et al. 1999), Grey-headed Flying-foxes are listed as ‘vulnerable’ under Inter-

national Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) criterion A2 because of a predicted 20% reduction

in population within the next 10 years, primarily due to habitat loss.

different management interventions isneeded to correspond with the vegetationmosaic. In all areas, however, weed was acommon and primary problem. Restorationwork which focused on weed control beganon the mid-slope near the Edward Streetaccess and progressively worked towardsthe watercourses and up to the privateproperty boundaries in a patchworkmanner (Fig. 2).

Bushland weed control treatments weresystematic, with detailed manual removal orprecision herbicide spraying of seedlings andherbaceous weeds and ‘cut and paint’ orstem injection herbicide treatments forlarger woody weeds and climbers. Thesetechniques conformed to those documentedin Wright (1991) and in the project reportslisted in Appendix I and are increasingly usedby volunteers and contract bush regenera-tors in Sydney bushland and beyond. Allexotic species were removed from each arearather than working on a species-by-speciesbasis.

Innovative tactics were developed aswork progressed. In some areas, forinstance, privets were injected with herbi-

cide up to 1 year before the herbaceousweed was to be removed.This prevented anew crop of privet seed forming while mostof the previous crop rotted among theherbaceous weed. In other areas (phase 1sites), work was carried out in a patchwork,initially leaving barriers of weed until anative understorey regenerated. Small areas(30 × 20 m) with high edge-to-area ratiosand surrounded by Trad and vines werefound, however, to be costly to maintain, sothese weed barriers were gradually elimi-nated. On steeply sloping sites, the weedinfestation was cleared in contour strips toprevent erosion and to maintain habitat forother fauna. Weeds along the private prop-erty boundary on the uphill side wereretained until native vegetation was estab-lished on the mid-slope to prevent wind-and water-borne weed propagules fromestablishing in the restoration area.Similarly,the creek banks were treated in short sec-tions to minimize erosion.

Trad was raked into rolls (1.5 × 10 m)along the contour. Periodic herbicide spray-ing and further rolling, ends-to-middle, pro-moted composting of this succulent weed.

This method successfully disposed of vastquantities of herbaceous weed, a farcheaper and more environmentally friendlyoption than carting it to landfill. Bothregular turning of composting weeds andwrapping weeds in heavy-duty black plasticfor more than 18 months was effective inkilling grass seeds and Trad stems.

Exotic vines that enveloped the canopyof existing trees: Madeira Vine (Anrederacordifolia), Morning Glory (Ipomoeaindica and I. purpurea), Balloon Vine (Car-diospermum grandiflorum) and Honey-suckle (Lonicera japonica); were removedwithin phase 1 and 2 areas and (beginningin 1994) were removed along StoneyCreek in an easterly direction (Fig. 2). Aconcerted effort was made annually toapply herbicide by the stem-scrapemethod, to kill vines in situ and (particu-larly in the case of Madeira Vine) to killexisting aerial tubers and prevent thedevelopment of more. Madeira Vine tuberswere picked from the soil once nativeseedlings began to regenerate andremoved to landfill. Madeira Vine regrowthwas spot sprayed with herbicide wherethere were no native seedlings. Althoughfloods bring more Madeira Vine tubersfrom upstream sources into the Reserve,this strategy has almost eliminated the pro-duction of tubers within the Reserve andthus protects the regenerating areas andbushland downstream in Garigal NationalPark from this threat.

Supplementary planting

Techniques other than weed control werealso used. During phase 1 and early in phase2, tubestock tree and shrub seedlings grownfrom locally collected seed were planted, incase the sites had no capacity for naturalregeneration. In hindsight, much of thiseffort was wasted as regeneration did occur.Buchanan (1985) stated that Blackbuttswere unlikely to survive under the changedconditions and recommended that Turpen-tines and Blue Gums (Eucalyptus saligna)be planted as replacement canopy species.In phase 3, planting or transplanting ofseedlings has been limited to canopyspecies: Blue Gums,Turpentines and Coach-woods (Ceratopetalum opetalum).

ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1. APRIL 2000 13

F E A T U R E

Figure 2. Habitat restoration areas, representing the various funding phases for the workscarried out at Flying-fox Reserve, Gordon.

14 ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1. APRIL 2000

F E A T U R E

Fire piles

Another technique that was being talkedabout in Sydney at the time,but about whichlittle was known,was the use of fire.This wasused for three reasons: to save the lugging ofhuge quantities of Lantana debris up to thestreet for costly removal by Council;becauseof the sheer volume of weed debris thatinhibited germination and; to trigger the ger-mination of any seed stored in the soil. Aftercomprehensive weed clearance, random firepiles were placed away from tree trunks andsandstone outcrops. Each pile measured nomore than 1 m high and was composed ofdry Lantana and privet stems, much of it lessthat 20 mm in diameter. Ku-ring-gai Councilor NSW Fire Brigade assisted in burningthese piles in spring or autumn (September1991, August/September 1992, September/October 1993, April 1995) on a day whenthe wind would not blow smoke to theflying-foxes or to the neighbours.

The following observations were madeabout the 27 piles burned in September1991. Flame heights ranged from 2 to 4 m.The hottest fires burned furiously for20 minutes and then died down and smoul-dered for several hours.The first pile was litat 10.10 hours and all piles were put outcompletely by hosing by 14.30 hours.Smoke from the fires was very localized due

to the dry nature of the piles and was notnoticeable beyond the immediate area.

Progress and someregeneration surprises

Results came quickly after weed control.Mature Blackbutts and Turpentines whosecanopies were previously dying back, beganto resprout along the trunks (Fig. 3). Exten-sive banks of Lantana and privet werereplaced with naturally regenerating ground-cover species (Table 1);particularly WeepingGrass (Microlaena stipoides), basket grasses(Oplismenus spp.), native geraniums (Gera-nium spp.), Kidney Weed (Dichondrarepens) and pennyworts (Hydrocotyle spp.).While the flying-foxes are not currentlyoccupying the regenerating vegetation at thewestern end of the Reserve, the new genera-tion of trees are filling gaps in the canopy toreplace the many dead trees which havefallen in recent years. Turpentine seedlingshave regenerated naturally in canopy gapsenlarged by falling dead trees. On the upperslopes, Blackbutt seedlings germinated onbare ground following weed clearing andpile burns (following a mass flowering ofBlackbutts in the summer of 1994). TheseBlackbutts have now reached 8 m in heightand continue to grow vigorously despiteperiodic defoliation by caterpillars.

In the areas where fire piles were used,a number of sclerophyll shrub speciesgerminated despite the apparent long-termabsence of parent plants in the above-groundvegetation (Fig. 4). Seeds of these specieshad presumably been stored in the soil fordecades, showing that the reintroduction ofthese species from other areas was unneces-sary. A volunteer used quadrats to collectquantitative data from six fire piles and fromrandomly selected adjacent unburnt areas ofa similar size. An analysis of data using one-way ANOVA found that the average number ofsclerophyll shrub species was significantlyhigher in the pile burn areas (F = 53.57; P =0.1) compared with the unburnt areas.Thesespecies also occurred in significantly higherdensities (F = 53.57; P = 0.01). The mostabundant species in the burnt areas were thesclerophyll shrubs, Green Wattle (Acaciaparramattensis) and Hop Bush (Dodonaeatriquetra); with Flax-leaf Wattle (Acacialinifolia) and Rusty Petals (Lasiopetalumferrugineum) occurring in lower numbers.Conversely, in the unburnt areas, nativegrasses were most abundant, particularly thebasket grasses and Weeping Grass (Micro-laena stipoides). On average, significantlyhigher numbers of native grass species werefound in the six unburnt areas comparedwith the burnt areas (F = 22.84; P = 0.01)and these occurred in significantly higherdensities (F = 5.02; P = < 0.05).

Overall, measurable progress has beenmade over the 15 years. The phase 1 and 2areas which were initially classified as WeedClass 4, are now Weed Class 1, requiringdecreasing maintenance weeding each year.The phase 3 areas are currently at Weed Class2 or 3 and will be needing regular work tomaintain them in the next couple of years.While these results are highly satisfactory,only approximately one-third of the largerReserve has received treatment; and theuntreated areas (particularly the easternsection of the Reserve, beyond the flying-foxcolony) is deteriorating rapidly due to contin-uing storm-water impacts, weed invasion andlack of fire to stimulate sclerophyll recovery.

Regeneration within thecolony site 1998–99

In 1985, some of the area currently occu-pied by the flying-foxes would have been

Figure 3. Left: damaged Turpentine canopy in 1985, Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox Reserve, Gordon(photo: R. Buchanan). Right: recovering Turpentine canopy in 1995, same location (photo: N. Pallin).

Spinebill (Acanthorhynchus tenuirostris)became more common.The Eastern YellowRobin (Eopsaltria australis), GoldenWhistler (Pachycephala pectoralis) andSatin Bower Birds (Ptilonorhynchus vio-laceus) occupy the dense vegetation alongthe creeks. A Superb Lyrebird (Menuranovaehollandiae) is seen periodically byregenerators and neighbouring residents.Native vertebrate species listed during bushregeneration or site inspections include sixmammals, 69 birds, 12 reptiles and threecommon frogs.Two threatened frog species(Mixophyes iteratus and Pseudophryneaustralis) were recorded in 1972 but havenot been reported since.

A pair of Powerful Owls (Ninox strenua)reside in the valley, feeding on flying-fox(Kavanagh 1993) and Ring-tail Possum(Pseudocheirus peregrinus; N. Pallin, pers.obs., 1999). Sea-eagles (Haliaeetus leuco-gaster) and the Diamond Python (Moreliaspilota ssp. spilota) are predators of flying-foxes and are seen occasionally. In 1989,traps were set over four nights for terrestrialmammals, resulting in the capture of BlackRats (Rattus rattus) and two male BrownAntechinus (Antechinus stuartii; R. & A.

ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1. APRIL 2000 15

F E A T U R E

classified as open forest vegetation (Specht1970) as it was dominated by Blackbutts(although, even then, ‘in a poor state ofhealth’). Black She Oak (Allocasuarinalittoralis) formed the next layer, withan understorey of sclerophyllous shrubs(Buchanan 1985). Since then, Trad, Lantana,Madeira Vine and other weeds have invadedfrom Stoney Creek and advanced eastwardswith the flying-foxes.

Removal of Trad, Lantana and MadeiraVine in July–September 1998 resulted innatural regeneration of native specieswithin 1 year. These include nine herb,three grass, four fern, six vine, six shrub andnine tree species, with some survivingplants having resprouted.The shorter lengthof time that the ground in this area has beenblanketed by weed may be significant in thespeedy recovery of the understorey.We haveyet to find what mix of understorey specieswill survive under a flying-fox colony on thissite when Trad is excluded. Flying-fox faecesappeared to cause burning on the leaves ofmany plants, including Turpentine seedlings.Turpentine and Blue Gum seedlings wereplanted outside the canopy of existing roosttrees and were protected initially with

plastic guards. In 12 months, some BlueGums had grown to 4 m and Turpentines to1.5 m. Approximately 10 per cent of theplanted seedlings had died.

Fauna diversity

The KBCS has collected the available infor-mation (plus its own observations) on theapproximate area occupied by the flying-foxes since 1972 and has marked all thisinformation on maps supplied by Ku-ring-gai Municipal Council (Fig. 1). These datawill be recorded on Ku-ring-gai Council’sgeographical information system.

Bush regenerators recorded their obser-vations of other fauna seen on the site, com-piling a fairly comprehensive fauna list. Anunusual dung beetle (Cephalodesmiusarmiger) which feeds on plant materialinstead of dung was identified with theassistance of the Australian Museum andCSIRO. As the vegetation became morediverse, moths, butterflies, frogs, EasternWater Dragons (Physignathus lesueurii),skinks, wrens (Malurus sp., Sericornisfrontalis), warblers (Gerygone mouki), fan-tails (Rhipidura spp.) and the Eastern

Table 1. Native species which regenerated on the site after weed removal

Herbaceous speciesAustrostipa pubescens*Carex appressaCentella asiaticaDianella caeruleaEchinopogon caespitosusEntolasia marginataEntolasia strictaGahnia sp.*Geranium homeanumGlycine sp.*Gnaphalium sphaericumGonocarpus teucrioidesImperata cylindricaIsolepis inundatusJuncus usitatusLepidosperma laterale*Lomandra longifoliaLomandra multifloraMicrolaena stipoidesOpercularia asperaOplismenus sp.Panicum simile*Persicaria spp.Plantago debilis*

Pseuderanthemum variabilePolymeria calcyinaPoranthera microphyllaPratia purpurascensRubus hilliiSigesbeckia orientalisSchelhammera undulataSenecio hispidulus*Veronica plebeiaWahlenbergia gracilis*Xanthosia pilosaXanthosia tridentaYoungia japonica

FernsAdiantum hispidulumBlechnum cartilagineumCalochlaena dubiaChristella dentataCyathea australisDoodia asperaDoodia caudataHypolepis muelleriPellaea falcata var. falcata Pteris tremula

ClimbersEustrephus latifoliusGeitonoplesium cymosumHardenbergia violacea*Hibbertia asperaHibbertia dentataKennedia rubicunda*Morinda jasminoidesPandorea pandoranaSmilax glyciphyllaTylophora barbata

ShrubsAcacia linifolia*Acacia longifolia* Acacia longissima*Breynia oblongifoliaDodonaea triquetra*Grevillea linearifolia*Lasiopetalum ferrugineum*Leucopogon juniperinusNotelaea longifoliaOzothamnus diosmifolius*Platysace lanceolata*Platysace linearifolia*

Polyscias sambucifoliusPultenaea flexilis* (died later) Zieria pilosa*Zieria smithii*

TreesAcacia parramattensis*Alphitonia exclesa Acmena smithiiCallicoma serratifolia*Ceratopetalum apetalumEleaocarpus reticulatusEleaocarpus kirtoniiEucalyptus pilularisFicus coronataFicus fraseriFicus rubiginosaGlochidion ferdinandiPittosporum undulatumPolyscias elegansSyncarpia glomuliferaSyzygium spp.Trema aspera

* Species whose germination was significantly improved by the addition of pile burns.

Williams, unpubl. data, 1989). With thechange in the vegetation during the primarystage of bush regeneration, there was adanger that feral birds, such as the CommonMynah (Acridotheres tristis) might invade.Fortunately, this has not occurred.

Contributions from theflying-foxes

The largest impact of flying-foxes ontheir roosting habitat is the contribu-

tion of nutrients to the colony site. Wiley

(1988) conservatively estimated that theycontributed 3 kg phosphorus per ha peryear in their droppings. Treadwell (1996)found soil phosphorus levels under theflying-fox colony of 429 ± 242 p.p.m. insummer and 496 ± 240 p.p.m. in winter.These levels were already two- to four-foldthe amount found in healthy bushland soilsof a similar type (Beadle 1962) and weremore than double the amount of 189 ± 77p.p.m. found under the colony by Wiley,8 years earlier.Treadwell (1996) concludedthat a total of 27 kg per ha had been addedto the colony site since 1988. Both studiesconcluded that the additional nutrientswere contributing to the weed growth, par-ticularly the dense ground cover of Trad.Treadwell concluded that the difference inphosphorus measurements betweensummer and winter was a result of the Tradutilizing the nutrient for growth in summerbut not in winter.

The bats have also had an effect on thefloristics of the site. In the areas used by thebats, an array of species known to be part ofthe flying-fox diet (as well as the usual arrayof herbaceous weeds) germinated aftercomprehensive weed removal exposed thesoil to sunlight.These, mainly rainforest-typespecies, included Sandpaper Figs (Ficuscoronata and F. fraseri), Port Jackson Fig(F. rubignosa), a few Moreton Bay Figs(F. macrophylla), Lilly Pillies (Acmenasmithii, Syzygium oleosum and S. panicu-lata), Blue-berry Ash (Elaeocarpus reticula-tus), Pigeon-berry Ash (E. kirtonii, althoughnot a known diet plant), Red Ash (Alp-hitonia excelsa), Giant Stinging Tree (Den-drocnide excelsa), Plum Pine (Podocarpuselatus), many species of exotic palms, vinessuch as Cissus spp., Morinda jasminoides,the exotic Mulberry (Morus nigra) andhuge numbers of the exotic, Tree Tobacco(Solanum mauritianum). Flying-foxestransport seeds of some of their diet plants,either in their mouths (for seeds greaterthan 4 mm in diameter) or their digestivetract, for small seeds (Eby 1996).

Some Australian native plants whichwere clearly not locally indigenous werereadily removed along with exotics, withothers requiring careful analysis to distin-guish whether they were artefacts of nearbyurban plantings or genuine extensions ofthe range of species occurring in rainforests

16 ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1. APRIL 2000

F E A T U R E

Figure 4. Top: prior to treatment in 1986, Lantana reached into the canopy (photo: N. Pallin).Middle: same view during phase 2 (1993) shortly after weed removal and during the burning of firepiles [note, second tree has fallen; (photo: M. Schofield)]. Bottom: native understorey regenerationin 1997, 4 years after treatment (photo: N. Pallin).

to the north or south of Sydney transportedby flying-foxes. Seedlings of Mulberry, TreeTobacco and palms were removed. It wasconcluded that Ficus fraseri represents anextension of range southward for thisspecies. The Stinging Tree seedlings died.Although Moreton Bay Figs are prime roosttrees at other colony sites, they do not natu-rally occur in the Sydney basin, so wereremoved. Pigeon-berry Ash grew to 6 mbefore its identity was confirmed, and thequestions remain, ‘where did it come fromand how did it get there?’

Public attitudes to flying-foxes

An initial barrier to success was the lackof knowledge of flying-foxes among thegeneral public, although this is clearlychanging. Ku-ring-gai historical recordscontain a photograph of a bat shootingparty taken early this century.When publicmoney was spent purchasing land toprotect the bat colony in the 1980s therewas a deluge of antibat letters in the news-papers which displayed ignorance of thesenative animals and no knowledge of theirecological roles. Some residents near theReserve objected vocally to the noise andsmell of the animals but over the years thesecomplaints have declined as residentsgained a better understanding of their wildneighbours. Some prospective home buyershave even phoned KBCS for information onthe bats and their possible impacts.

Public understanding and acceptance iscrucial for long-term environmental conser-vation programmes.The KBCS has been pre-senting live, hand-reared flying-foxes to thepublic since 1985. This approach did moreto change people’s attitudes than wordsever could. By seeing a flying-fox close up,many myths were dispelled. We couldexplain new information coming from batresearchers to people at fetes, to Scouts andGuides, community group meetings andeven in the Council Chambers. KBCS tooktheir presentation on the Grey-headedFlying-fox into schools, gaining curriculumapproval from the Department of Educa-tion.

Other methods of spreading informationinclude publishing the Friends of Batsnewsletter,which keeps members up to date

on bat issues and is now up to its 54th issue.The KBCS encourage people to view theevening exodus of the flying-foxes from anobservation point at the nearby RosedaleRoad bridge, which is spectacular onsummer evenings. Here, pictorial signsexplain the pollination and seed dispersalservices provided by flying-foxes.More infor-mation is available on five educational signsat the nearby Kukundi Wildlife Shelter inLane Cove National Park where the educa-tional boards about flying-foxes are onpermanent public display. While theseprogrammes do much to change attitudes, aprimary consideration is that visitor pressureis deflected away from the colony site andthe regenerating vegetation in the Reserve.

The discovery, in 1996, of the flying-fox-borne virus, Australian Bat Lyssaviruswhich can only be contracted through bitesand scratches from bats, has not helpedKBCS efforts to promote a positive attitudetowards bats. Indeed, requests for bat talkstemporarily dropped after the discoveryand, given the need for vaccination for bathandlers and its high cost, the number ofpeople available to give talks has been slowto increase. Fortunately, however, the adventof the virus has not affected funding for theHabitat Restoration Project which contin-ues with a Natural Heritage Trust grant(1998–2000) and Ku-ring-gai Bat Conserva-tion Society members have maintained theirmoral and financial support.

Keys to success to date

While we are aware that our successes arerelatively small compared with the size ofthe ongoing, broader, urban degradationproblem, the most fundamental ingredientof success to date has been the support ofthe volunteer bush regenerators. A numberhave devoted more than 10 years to theproject and collectively contributed approx-imately 1000 hours per annum. Further-more, the contract bush regeneratorsemployed on the project showed a willing-ness and enthusiasm for the project farbeyond their monetary rewards, and wereoften prepared to exchange ideas with thevolunteers during their lunch break. Bothcontract and volunteer bush regeneratorshave contributed their observations for theflora and fauna species lists for the Reserve.

Volunteers also contributed to a census offlying-foxes in the valley, estimated weekly(December 1994–November 1997) by‘counting’ the animals as they flew out ofthe valley at dusk. ‘Counts’ continuemonthly, providing a comparative record ofoccupation of the site.

Another key to successful management isacknowledging that a regeneration pro-gramme must be sufficiently flexible to workwith unpredictable natural events and sea-sonal opportunities. This periodic nature ofregeneration was highlighted in the summerof 1998–99, for instance, when Coachwoodunderwent a spectacular flowering. Addi-tional areas were cleared of Trad to takeadvantage of the massive fall of seed, anaction which resulted in the germination ofthousands of Coachwood seedlings. As theseevents do not occur annually, restorationprogrammes must be flexible enough to takeadvantage of these opportunities becausethe next event may be 5 or 10 years away.

Another essential ingredient has beenthe support of workers from other sites,such as Dr John Stockard who has consider-able experience with both flying-foxes andregeneration at Wingham Brush in northernNSW. Scientists shared their knowledge ofbats, freely giving their time and expertise tospeak at the ‘Friends of Bats’ events whichKBCS has held twice each year since 1987.

Last, but certainly not least, there hasbeen good support from the land manager,Ku-ring-gai Council and from the NSWNational Parks and Wildlife Service. Councilcontinues to provide an annual allocation of$10 000 to maintain the increasing area ofregenerating forest. A Voluntary Conserva-tion Agreement was signed between Ku-ring-gai Municipal Council and the NSW Ministerfor Environment in 1991 to protect Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox Reserve in perpetuity. A grantunder this agreement was used to installinterpretive signage, gross pollution trapsand conduct research in collaboration withthe University of NSW on soils and radio-telemetry of rehabilitated flying-foxes fol-lowing their release (Augee & Ford 1999).

Continuing challenges

A number of unique challenges have com-plicated the task of achieving the project’sgoals.One of these has been the difficulty of

ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1. APRIL 2000 17

F E A T U R E

18 ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1. APRIL 2000

F E A T U R E

Why we volunteer: Some of the longer-term volunteers tell their own story

Apart from the current team of 10, 67 volunteers haveassisted at Flying-fox Reserve over the years collectivelycontributing approximately 1000 hours per annum. Anumber have devoted more than 10 years to the project.

Elizabeth Hartnell, one of the original team andstill working after 12 years, remembers a time whenLantana was so thick that the team had to make tunnels

to get to work. ‘I remember one time I was late and got myself lost under the Lantana. I had to just go back up hill to find my wayout. When we gradually cleared the Lantana nothing was growing except the mature native trees. But before long, there was themiracle of seeing natives germinating. That is the joy that drives us, because the native trees are so important to the canopy.’

‘You get some inner satisfaction and peace in going down and just “bush regenerating”. We have some very good talks, andjokes and fun. But also if you are not wanting to talk with someone, it is very easy not to. And you see the way the area changeswith the response of the different plants over different seasons. And there are also birds and an awful lot of invertebrates to whichwe draw each other’s attention, little moths or butterflies, spiders.’

Margaret Beavis, another 12-year volunteer, gets satisfaction from seeing the ‘good’ bush come back again in an area thatwas degraded. ‘I get a big thrill out of that. What I am interested in is the bush becoming a self-supporting, varied system, withas much diversity as we can reasonably maintain. I don’t go in for planting. I just prefer that things happen naturally. It’s a delightto look back at that now. You have an image at the back of your mind of what it looked like then. And to see it now is just anabsolute joy. And you realize that it’s part of you by now, because you know every inch of the way. We really have battled therebecause it was so degraded before.’

‘And I’ve met some really good friends there. That meant a lot to me. We talk about all sorts of things, from palaeontology,languages, travels, politics, and operas to, of course, environmental issues. Always interesting.’

Like many others, Gerda Cohen is mainly motivated to help the bats. ‘The unusual thing is they live so close to us. It is sosatisfying that their home can be so close to our home, as if they trust us to look after them. The place was so terribly infestedwith weeds. And we actually see it from month to month. When we come back to a site on which we worked we just can’t believehow wonderful it is — what a response the bush gives to our work.’

‘When I work, I prefer to be silent and have silence around me. So everybody finds something that they want, whether it iscompanionship or solitude. But what is reassuring is that you actually don’t need to do a big chunk of work at a time. You justdo the little bits and the little bits eventually join. It is the love of the work, as well and you know you can make a difference.’

Making a difference also depends upon the drive and inspiration of the team leaders — and the success of the project is in nosmall measure due to the guidance and inspiration of Nancy Pallin. ‘It’s actually very exciting. The world might appear to befalling apart but I think there’s a huge number of people saying, “Well, hang it. I’m not going to let that happen.” By the time I’mdead, it won’t matter. But it will matter for the younger people. I say to them. ”Let’s do it.” And they look at you as if you are abit mad. But next time they see you they say “You’re right, you know. We’ve got to do it” So, it’s good stuff.’ ™

Tuesdays are sacrosanct to the workers

at ‘the Bat Colony’. Every week for 12

years so far, small numbers of volunteers

have been meeting on site to transform it

from a highly weed-infested site to what

is now a healthy-looking bushland area

with a strong native understorey.

Bat Colony volunteers taking a break from work in Area 4 in the early 1990s(clockwise from front left: Maree Treadwell, Nancy Pallin, Marjorie Beck, ElizabethHartnell, Anne Ringwood, Roma MacGregor, Margaret Beavis and Eileen Davies).

ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1. APRIL 2000 19

F E A T U R E

addressing urban storm-water dischargesthat were repeatedly disturbing treated sitesand delivering fresh weed seed, road gravel,silt and litter from surrounding streets.Three experimental gross pollution trapshave been placed in street drains to collectmaterial before it enters the Reserve.Whenthe traps were cleaned they were found tocontain 60% soil fractions, 35% vegetativematter and 5% plastic bottles and other litter(L. Hardy, Ku-ring-gai Council, pers. comm.,1999). The solids block the water channel,causing further scouring and depositionacross hillsides which are not naturaldrainage lines. Regular cleaning of the trapswill prevent this problem, but is a cost thecommunity as a whole must bear to protecturban bushland from further deterioration.

Arguably, the most important challenge isthat major sources of exotic invasive treesand shrubs still exist in the broader StoneyCreek catchment and are readily redis-persed by native fauna, particularly Curra-wongs (Strepera graculina; Buchanan1989). Although Ku-ring-gai Council haspolicies for control of noxious and environ-mental weeds, the majority of residents areonly able to identify a couple of them andare mostly ignorant of weed dispersal oreffective weed removal methods. Someprogress was made with a pilot ‘Backyard,bush-friendly’ programme conducted in1995–96 by Ku-ring-gai Council and fundedby the Voluntary Conservation Agreementgrant. Further personal contact by KBCSmembers has convinced a few more neigh-bours to replace their weeds with localindigenous species but progress has beenpatchy.

A broad-scale environmental educationprogramme is needed to involve the major-ity of landowners in weed removal andreplacement with locally indigenous flora,from the ground covers to the treetops.Until the landscape scale weed problem isresolved the Habitat Restoration Project willhave to continue with considerable annualmaintenance costs.

A ‘take home’ message

Flying-foxes not only need colony sites inwhich to roost, but also food resourcesacross the landscape.The continuing loss ofindigenous trees, especially Blue Gums,

Blackbutts, Turpentines, ironbarks, blood-woods and angophoras (caused by furtherdevelopment in surrounding suburbs) is aloss of their food resources. The KBCSbelieves that, in the same way public supporthas been harnessed for the flying-foxes, itcan also be stimulated for restoration ofnative vegetation in the catchment. If resi-dents were shown that low maintenanceindigenous gardens could save them fromthe drudgery of mowing and the costs ofwatering — and give them the delights ofwrens, fantails and water dragons outsidetheir windows — habitat restoration couldtake place across whole valleys, even in anurban setting.

Acknowledgements

Without the wise counsel of Elizabeth

Hartnell, Chairperson of the Ku-ring-gai

Bat Colony Committee Inc 1985–95, the

Habitat Restoration Project would not have

been possible. Madeleine Schofield,

manager of Indigenous Regeneration Co.

and site supervisor, Gordon Limburg, con-

tributed superior bush regeneration skills

to tackle a formidable restoration project.

Gordon Limburg compiled the original

species lists for the Reserve and Tein

McDonald collected and analysed the

regeneration data after fire. Robin

Buchanan has inspired and educated thou-

sands of bush regenerators and kindly

inspected the Habitat Restoration Project

and commented on its progress (Habitat

Restoration Project Report 1994–95). I

thank everyone who has contributed. All

photographs are from the collection of Ku-

ring-gai Bat Conservation Society.

ReferencesAugee M.L. and Ford D. (1999) Radio-tracking

studies of Grey-headed Flying-foxes, Pteropuspoliocephalus, from the Gordon colony, Sydney.Proceedings of the Linnean Society of NSW121: 61–70.

Beadle N. C. W. (1962) Soil phosphate and thedelimitation of plant communities in easternAustralia II. Ecology 43, 281–288.

Buchanan R. (1983) Ku-ring-gai Municipal CouncilBushland Management Survey, 1. Results andDiscussion. Ku-ring-gai Municipal Council,Gordon, NSW.

Buchanan R. (1985) Site Assessment of the GordonBat Colony — Weed Control and Restoration ofNative Vegetation. Ku-ring Bat Colony Commit-tee, Gordon, NSW.

Buchanan R. (1989) Pied Currawongs (Strepera gra-culina): the diet and role in weed dispersal in sub-urban Sydney, New South Wales. Proceedingsof the Linnaean Society of NSW 111, 241–255.

Buchanan R. M. (1990) Bush Regeneration: Recov-ering Australian Landscapes. TAFE LearningPublications, Sydney.

Duncan A., Barry Baker G. and Montgomery N., eds(1999) The Action Plan for Australian Bats. Envi-ronment Australia, Canberra.

Eby P. (1991a) ‘Finger-winged night workers’: man-aging forests to conserve the role of Grey-headed flying foxes as pollinators and seeddispersers. In: Conservation of Australia’sForest Fauna (ed. D. L. Lunney), pp. 91–100.Royal Zoological Society of NSW, Mosman.

Eby P. (1991b) Seasonal movements of Grey-headed flying foxes, Pteropus poliocephalus(Chiroptera: Pteropodidae), from two maternitycamps in northern New South Wales. WildlifeResearch 18, 547–559.

Eby P. (1995) The Biology and Management of FlyingFoxes in NSW. Species Management Reportno.18. NSW National Parks and WildlifeService, Hurstville.

Eby P. (1996) Interactions Between the Grey-Headed Flying Fox Pteropus poliocephalus(Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) and its Diet Plants –Seasonal Movements and Seed Dispersal. PhDThesis, University of New England, Armidale.

Kavanagh R. (1993) Fruit bats contribute to urbanconservation of the powerful owl. Friends ofBats Newsletter, 29. Ku-ring-gai Bat ColonyCommittee Inc.

Ku-ring-gai Municipal Council (1999) Ku-ring-gaiFlying-fox Reserve Management Plan. Ku-ring-gai Municipal Council, Gordon, NSW.

McWilliam A. N. (1984) The Gordon Fruit BatColony, Sydney. Report for (NSW) NationalParks & Wildlife Service. NSW National Parks &Wildlife Service, Hurstville.

Parry-Jones K. A. (1993) The Movement of Ptero-pus poliocephalus In New South Wales. PhDThesis, University of New South Wales, Kens-ington.

Parry-Jones K. A. and Augee M. (1991) Food selec-tion in Grey-headed flying foxes (Pteropus polio-cephalus) occupying a summer colony site nearGosford, NSW. Wildlife Research 18,111–124.

Puddicombe R. (1981) A Behavioural Study of theGrey Headed Flying Fox (Pteropus polio-cephalus). B.Sc. (Hons) Thesis, University ofNew England, Armidale.

Robinson M. (1973) Flying foxes breeding atGordon, Sydney. Australian Bat Research News12, 2.

Specht R. L. (1970) Vegetation. In: The AustralianEnvironment, 4th edn, (ed. G. W. Leeper), pp.44–67. CSIRO and Melbourne University Press,Melbourne.

Stockard J. (1996) Restoration of Wingham Brush1980–96. In: Eleventh Australian Weeds Con-ference Proceedings (ed. R. C. H. Shepherd),pp. 432–436. Weed Science Society of VictoriaInc., Frankston.

Tidemann C. R. (1995) Grey-headed flying-fox Ptero-pus poliocephalus. In: The Mammals of Australia(ed. R. Strahan), pp. 439–441. Reed Books,Chatswood.

Treadwell M. (1996) The interactions betweenPteropus poliocephalus and habitat within theKu-ring-gai Flying-fox Reserve, Gordon, NSW.

Thesis for Graduate Diploma, School of Bio-logical Sciences, University of NSW.

Wiley L. (1988) Phosphorus Levels at the BatColony Site, Gordon, and the Effects ofIncreased Levels of Phosphorus on the Germi-nation and Seedling Growth of Syncarpia glo-mulifera, Eucalyptus pilularis and Angophoracostata. Thesis for partial fulfillment of B. Sc.(Hons) Macquarie University, Ryde.

Wright P. (1991) Bush Regenerators’ Handbook,2nd edn. The National Trust of Australia(NSW), Sydney.

Appendix I. List of projectreports describingtreatments applied at Flying-fox ReservePallin N., Hartnell E. and Limburg G. (1991) First

Four Years of the Habitat Restoration Project atthe Ku-ring-gai Bat Colony, Gordon, NSW Aus-tralia, March 1987 to March 1991. Ku-ring-gaiBat Colony Committee, Gordon.

Schofield, M. and Limburg G. (1991) Ku-ring-gaiFlying-fox Habitat Restoration Project 1991.Indigenous Regeneration Co., Gordon.

Ku-ring-gai Bat Colony Committee Inc. & IndigenousRegeneration Co. (1993) Report on Habitat

Restoration Project in Ku-ring-gai Flying FoxReserve Phase 2: 1992–93. Ku-ring-gai BatColony Committee Inc. and Indigenous Regen-eration Co., Gordon.

Ku-ring-gai Bat Colony Committee Inc. & IndigenousRegeneration Co. (1995) Habitat RestorationProject, Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox Reserve, Gordon,continuation Phase 2: 1994–95. Ku-ring-gai BatColony Committee Inc. and Indigenous Regen-eration Co., Gordon.

Ku-ring-gai Bat Colony Committee Inc. & IndigenousRegeneration Co. (1997) Habitat RestorationProject in Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox Reserve,Gordon, Completion Phase 2: 1996–97. Ku-ring-gai Bat Colony Committee Inc. and Indige-nous Regeneration Co., Gordon.

20 ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT & RESTORATION VOL 1 NO1. APRIL 2000

F E A T U R E