Explorations into the World of Lewis and Clark Volume I Sample

-

Upload

digital-scanning-inc -

Category

Documents

-

view

109 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Explorations into the World of Lewis and Clark Volume I Sample

i

Explorations into the World of Lewis and Clark194 Essays from the Pages of We Proceeded On.

ii

Captain William Clark Captain Meriwether Lewis

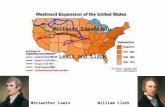

When Lewis and Clark returned from their expedition across the trans-Mississippi West to the Pacific Coast they were proclaimedheroes by the American public. Charles Willson Peale, founder and curator ofthe Philadelphia Museum, and a pre-eminent portrait artist, who had paintedthe portraits of several of the colonial and Revolutionary greats, requestedpermission to paint the portraits of the two new American heroes upon theirvisit to the states. The two officers agreed and the above portraits weredone—Meriwether Lewis’s in March 1807, and William Clark’s three yearslater. Today the Portraits are prime holdings of Independence National HistoricPark in Philadelphia.

iii

Explorations into the Worldof Lewis and Clark:

194 Essays from the pages of We Proceeded On

Edited with Introductions and Notes

by

Robert A. Saindon

VOLUMEI

ISBN 1-58218-762-2

v

Dedication

Eldon George Chuinard, M.D. (1904-1993)

Knowing the late Dr. Eldon G. (“Frenchy”) Chuinard was both a pleasureand an inspiration. He was a gentleman with tenacity, a scholar with

enthusiasm, and a friend with devotion. Although orthopedic surgery (for which hegained international fame) was his profession, he maintained an abiding love forLewis and Clark, often referring to one or the other as his friend.

His interest in the Expedition began at the age of ten and continued the remainingseventy-eight years of his life. He was a member of the 1964 United StatesCongressional Lewis and Clark Commission, and helped establish the modern trailroute. He was a founding father of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation,and served as the Foundation’s second president. He was a long-time chairman ofthe Oregon Governor’s Lewis and Clark Trail Committee; and was instrumental inthe establishment of various Lewis and Clark interpretive signs, and memorials.

Frenchy was the author of the scholarly, yet popular, book Only One ManDied: The Medical Aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which has seenseveral printings since it was first published in 1979.

He founded We Proceeded On, the quarterly publication of the Lewis andClark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. It was, therefore, because of those effortstwenty-five years ago that the publishing of the present anthology of Lewis andClark essays was ultimately made possible.

To paraphrase from the words of Oregon Governor Barbara Roberts whenpresenting the 1993 Thomas Jefferson Honored Citizen Posthumous Award toFrenchy: We proudly honor the worth of Dr. Chuinard’s lasting imprint upon thefabric of our treasured Lewis and Clark heritage, and in so doing we dedicate thepresent work to his beloved memory.

vii

Contents

VOLUME ONE

Dedication. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .vIllustrations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .xviiiForeword. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xxiEditorial Procedures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xxiiiPreface/Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xxviIntroduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xxviii

IBefore Lewis and Clark

Introduction to Section I . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

George Vancouver1. “Vancouver’s Legacy to Lewis and Clark”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. Arlen J. Large 3

Alexander Mackenzie2. “Mackenzie’s Wonderful Trail to Nowhere”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 113. “The Realities and Complexities of Food for Sir

Alexander Mackenzie, (1789)” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Jim Smithers 19

Don Martin de Sasse/Alexander Mackenzie4. “North and South of Lewis and Clark”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 23

Russia/Great Britain/Spain/United States/France5. “International Interpretation and ‘Internationalist’s’ Interpretation

of the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . James A. Gardner 31

Jean LaPerouse6. “Of Rivers and Oceans: Comparing the Lewis and Clark

Expedition with that of LaPerouse”. . . . . . . . . . . Robert R. Hunt 47

Menard7. “Old Menard”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert A. Saindon 59

viii

IIExpedition Preparations:

Introduction to Section II . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

Persons—Thomas Jefferson8. “Thomas Jefferson and the Pacific Northwest” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Donald Jackson 709. “The American Philosophical Society

and Thomas Jefferson”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Carol Lynn MacGregor 7910. “Trailing Lewis and Clark: ‘The Spirit of Discovery’”. . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 8911. “Lewis and Clark Under Cover (Secrecy Involving the

Expedition—A Cipher-Text Letter)”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 93•Boxed Feature: “Portable Soup” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103—Meriwether Lewis12. “Meriwether Lewis: Devoted Son” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Mary Newton Lewis 10413. “Lewis...in Washington”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 11314. “The Phantom Farmer: Lewis and the American

Board of Agriculture” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 12215. “Meriwether Lewis at Harpers Ferry”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Joseph D. Jeffrey 12616. “Captain Lewis and the Hopeful Cadet”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 136

—William Clark17. “Clark And Lewis Homeplaces” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Jane Henley and Guy Benson 14118. “Clark Land in Virginia and the Birthplace

of William Clark” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..Robert E. Gatten, Jr. 145

—Andrew Ellicott19. “Andrew Ellicott—Astronomer, Mathematician, Surveyor . . . . . . . . . . . . . Nancy M. Davis 154

Finances20. “$25,000 Vs. $38,722.25: The Financial

Outlay for the Historic Enterprise. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert E. Lange 16121. “President Jefferson’s Letter of Credit: Why so Many Copies?”. . . Robert A. Saindon 165

Places22. “A Grand Tower”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ann Rogers 17023. “Lewis and Clark and the American Bottom” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Linda Mizell 17624. “St. Louis in 1804” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Frances H. Stadler 18325. “Where did the Lewis and Clark Expedition Start?”. . . . . . . . . .Eldon G. Chuinard 19226. “Where the Trail Begins: The Illinois Legacy to

the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Everett L. Sparks 200•Boxed Feature: “The Widow Lady—Another Candidate”. . . . . . . . . . . . Bob Moore 207

Events27. “Changing (Louisiana) Territorial Ownership: “Louisiana’s Irrelevant

Flag: Lewis and Clark Were Going Anyway”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 208Articles

28. “The Not So Enigmatic Lewis and Clark Air Gun”. . . . . . . . . . . . .Roy M. Chatters 218

Contents

ix

•Boxed Feature: “Lewis’s Airgun as Mentioned in the Journals”. . . Robert E. Lange 221

IIIExpedition Personnel

Introduction to Section III . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222

In General29. “Expedition Specialists: The Talented

Helpers of Lewis and Clark”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 22330. “Additions to the Party: How the Expedition Grew and Grew”. . . . Arlen J. Large 232

Non-Commissioned Officers—Sergeant Charles Floyd31. “Dr. Elliott Coues and Sergeant

Charles Floyd”. . . . . . . . ... . ... . . . . . .Paul R. Cutright and Michael J. Brodhead 24232. “Monuments to ‘A Young Man of Much Merit’”. . . . . . . . . . ..James J. Holmberg 251—Sergeant Patrick Gass33. “Sergeant Patrick Gass: Irishman? Scotsman?”. . . . . . . . . . . . . Eldon G. Chuinard 26734. “The Photographs of Sergeant Patrick Gass” . . . . . . . . . . . . . Eldon. G. Chuinard 26935. “The Patrick Gass Photographs and Portraits: A Sequel.”. . .Jeanette D. Taranik 274—Sergeant Nathaniel Pryor36. “ Sergeant Nathaniel Pryor of the Lewis

and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert E. Lange 280—Corporal Richard Warfington37. “Corporal Richard Warfington’s Contribution

to the Expedition” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert E. Lange 283

Enlisted Men—William Bratton38. “William Bratton: One of Lewis and Clark’s Men”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert E. Lange 285•Boxed Feature: “Supplemental Note on William Bratton” . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert E. Lange 292—Private John Colter39. “John Colter: One of Lewis and Clark’s Men”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Barbara Kubik 29340. “John Colter: RIP”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ruth Frick 305—Privates Joseph and Reuben Field41. “The Expedition’s Brothers: Joseph and Reuben Field”. . . . . . . . Robert E. Lange 312—Robert Frazer42. “Frazer’s Mutiny”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 315—Private John Newman43. “The Court-Martial of Ensign Meriwether Lewis (Some Observations

to the Court-Martial of the Expedition’sPrivate Newman)”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Eldon. G. Chuinard 317

—Private George Shannon44. “Private George Shannon: The Expedition’s

Youngest Member, 1785 or 1787-1836”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert E. Lange 324—John Shields45. “John Shields: Lewis and Clark’s Handyman:

Contents

x

Gunsmith, Blacksmith, General Mechanic”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert E. Lange 335—Private Alexander Hamilton Willard46. “The Gravesite of the Expedition’s

Alexander Hamilton Willard” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Wilbur Hoffman 340•Boxed Feature: “Additional Information on Alexander Willard. . . . . . . .Robert E. Lange 343

Non-Military Personnel—Jean Baptiste Charbonneau47. “A February Birthdate: An Infant Explorer

Joins the Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .William C. Adreon 344—Toussaint Charbonneau48. “Poor Charbonneau! Was He as Incompetent as the

Journals/Narratives Make Him Out to Be?”. . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert E. Lange 347—George Drouillard49. “George Drouillard: One of the Two or Three

Most Valuable Men on the Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert E. Lange 35350. “George Drouillard and For Massac”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Jo Ann Brown 357—Engages51. “New Light on Some of the Expedition Engages”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Jo Ann Brown 363—Sacagawea52. “Sacajawea? Sakakawea? Sacagawea?

Spelling, Pronunciation, and Meaning”. . . . . . . . . . . . . Irving W. Anderson 37153. “Sacajawea, Boat-launcher: The Origin and

Meaning of a Name...Maybe”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert A. Saindon 37554. “The Abduction of Sacagawea”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert A. Saindon 38355. “Sacagawea and Sacagawea Spring”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Eldon. G. Chuinard 38856. “Sacagawea, the Guide, Vs. the Purists”. . . . . .Arlen J. Large and Edrie L. Vinson 39157. “Another View of Sakakawia. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Calvin Grinnell 39958. “One Remarkable Lady: An Interview

with Blanche Schroer”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Marie Webster Weisbrod 40559. “Sacagawea—Her Name and

Her Destiny”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Irving W. Anderson and Blanche Schroer 412—Seaman60. “Call Him a Good Old Dog, But Don’t Call Him Scannon”. . . . . . Donald Jackson 41961. “Seaman’s Trail: Fact Vs. Fiction” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Louis Charbonneau 422

Index to Volume One. . . . . . . . . .

VOLUME TWO

IVPeople, Places, Things, and Events Along the Trail

Introduction to Section IV. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 427

In General62. “In the Wake of the Red Pirogue: Lewis and Clark and the

Exploration of the American West”.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .John Logan Allen 428

Contents

xi

63. “A Most Perfect Harmony: Life at Fort Mandan”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . James P. Ronda 44164. “The Summer of Decision: Lewis and

Clark in Montana, 1805”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . John Logan Allen 44965. “Imagining the West Through the Eyes of Lewis and Clark” . . . . James P. Ronda 459

People (Non-Indian)—Joseph Graveline66. “Joseph Gravelines and the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . Paul C. Graveline 468—Place Names67. “All in Family—The In-house Honorifics of Lewis and Clark”. . . .Arlen J. Large 472

Places—Spirit Mound68. “Lewis and Clark and the Legend of the ‘Little People’”. . . . . Robert A. Saindon 478—Knife River Villages69. “Knife River Indian Villages”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Gary E. Moulton 48270. “The Sakakawea (Awatixa) Site”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..Erik Holland 484—Among the Mandans71. “Fort Mandan: Wilderness Preparation Headquarters”. . . . . .Alan R. Woolworth 488—Lewis and Clark Graffiti72. “They Left Their Mark: Tracing the Obscure Graffiti

of the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert A. Saindon 492—Slaughter River Pishkun73. “Slaughter River Pishkun or Float Basin?” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .W. Raymond Wood 504—Great Falls Portage74. “The Great Portage—Lewis and Clark’s Overland

Journey Around the Great Falls of the Missouri”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Larry Gill 510— Jefferson River75. “‘Clark’s Lookout’: An Interpretation of

an Age-Old Landmark” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert A. Saindon 517—Lolo Trail76. “Along the Lolo Route”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Carol Lynn MacGregor 522—Fort Clatsop77. “The Western End of the Lewis and Clark Trail” . . . . . . . . . . . . Eldon G. Chuinard 528—Horse Trading78. “Captain Clark’s Plan to Enter into the

Horse Trade Business”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert A. Saindon 538—Pompey’s Pillar79. “Pompey’s Pillar: Should Mere Fragments of Facts

Become a ‘General’ Conclusion?”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 54080. “‘My Boy Pomp’: About the Name”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Joseph A Mussulman 547

Things:—Flags81. “Symbol of Peace, Sign of Allegiance, Banner of Pride: The

Flags of the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert A. Saindon 552—Espontoons82. “The Espontoon: Captain Lewis’s Magic Stick” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert R. Hunt 561

Contents

xii

83. “The Espontoons of Captains Lewis and Clark” . . . . . . . . . . . .Howard Hoovestol 569—The Corn Mills84. “The Mystery of the Third Corn Mill” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . John H. Stofiel 572—Survey Instruments85. “The Instruments of Lewis and Clark”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Martin Plamondon II 575

Events:86. “Luck or Providence—Narrow Escapes on the

Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert R. Hunt 58187. “Christmas Came Three Times to the Corps of Discovery” . . . . . Robert E. Lange 59188. “The Leapfrogging Captains” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 59789. “The Brig Lydia Misses a Rendezvous with History”. . . . . . . . . Robert E. Lange 60190. “The Empty Anchorage: Why No Ships

Came for Lewis and Clark”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 60791. “Riled Up Blackfeet: Did Meriwether Lewis Do It?”. . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 61492. “Was it the Pawpaw?”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ann Rogers 624

Transportation:—Boats93. “The White Pirogue of the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . Robert A. Saindon 62794. “A Note on the White Pirogue” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Gary E. Moulton 63695. “The Rocky Boat Ride of Lewis and Clark

(All Boats of the Expedition)” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 63896. “Captain Lewis’s Iron Boat: The Experiment”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Donald W. Rose 648—Horses97. “Hoofbeats and Nightmares (A Horse Chronicle

of the Lewis and Clark Expedition”) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert R. Hunt 655

Fishing:98. “Incompleat Anglers on the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . Robert R. Hunt 670

Foods and Drinks99. “Gills and Drams of Consolidation: Ardent Spirits

on the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert R. Hunt 680100. “Where’s the Salt”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Donald Nell 700101. “The Making of a Myth: Did the Corps of Discovery

Actually Eat Candles?”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert J. Moore, Jr. 710Military Life

102. “Crime and Punishment on the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . Robert R. Hunt 716

Clothing and Shelter103. “Mockersons: An Unspoken Tongue”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert R. Hunt 733104. “The Clothing of the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . .Robert J. Moore, Jr. 742105. “A Closer Look at the Uniform Coat of the

Lewis and Clark Expedition. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert J. Moore, Jr. 754106. “Tent Shreds and Pieces: Nomadic Shelter

of the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert R. Hunt 761Fun and Games

107. “Fun and Games on the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . Robert R. Hunt 773108. “Merry to the Fiddle Music: The Musical Amusement

Contents

xiii

of the Lewis and Clark Party”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert R. Hunt 784109. “Men in High Spirits—Humor on the

Lewis and Clark Trail”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Joseph A Mussulman 796

V.Scientific Aspects of the Expedition

Introduction to Section V . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 806

General110. “Soundscapes. . .The Sonic Dimensions of the

Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Joseph A. Mussulman 807Plants

—General111. “The Military Naturalists: Lewis and

Clark Heritage”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Michael J. Brodhead 815112. “Well-Traveled Plants of Lewis and Clark” . . . . . . . . . . . . .Paul Russell Cutright 824—Roots113. “Lewis and Clark’s Wapato: Endangered Plant,

Fight for Survival”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..Roy D. Craft 829—Trees114. “Meriwether Lewis and His Cedar Tree”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Bob Holcomb 836—Flowers115. “Cleome integrifolia the Third”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Paul Russell Cutright 841

Animals—Prehistoric116. “Lewis and Clark and Dinosaurs” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert J. Moore, Jr. 847—Mammals117. “Lewis and Clark Meet the ‘American Incognitum’”. . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 852118. “Pronghorns as Documented by the 1804–1806

Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ken Walcheck 861119. “Lewis and Clark in Buffalo Country” . . . . . . . . . . .Raymond Darwin Burroughs 869—Birds120. “Birds of the Lewis and Clark Journals”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Virginia C. Homgren 875121. “A Summary of Birds Seen by Lewis and Clark”. . . . . . . . . . Virginia C. Homgren 885122. “A Glossary of Bird Names Cited by

Lewis and Clark.”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Virginia C. Homgren 890123. “A History of Lewis’s Woodpecker and

Clark’s Nutcracker”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Paul Russell Cutright 903

Reptiles and Amphibians124. “Herpetology on the Lewis and Clark Expedition 1804–1806”. . Keith R. Benson 916

Astronomy125. “Lewis and Clark: Part Time Astronomers”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 928

Contents

xiv

Geography/Cartography126. “John Thomas Evans and William Clark: Two Early

Western Explorers’ Maps”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . W. Raymond Wood 933127. “The Maps of the Lewis and

Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Elizabeth Langhorn and Guy Benson 942128. “Another Look at William Clark’s Map of 1805”. . . . . . . . . . . . . .Gary E. Moulton 947129. “Fort Mandan’s Dancing Longitude”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 953130. “The Three Forks of the Missouri River: The Jefferson,

Madison and Gallatin Rivers” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert E. Lange 960131. “The Mountain Passes”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert E. Lange 964

Meteorology132. “‘. . .it thundered and lightened,’ The Weather Observations

of Lewis and Clark”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 969133. “The Expedition and Inclement Weather of

November-December, 1805”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert E. Lange 977

Ethnography, Ethnology, Philology134. “The Names of Nations: Lewis and Clark as Ethnographers”. . .James P. Ronda 982135. “Lewis as Ethnographer: The Clatsops and Shoshones”. . . . Stephen Ambrose 993136. “Lewis as Ethnographer: The Clatsops and Chinooks”. . . . . .Stephen Ambrose 1000137. “Games Sports and Amusements of Natives Encountered

on the Lewis and Clark Expedition” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert R. Hunt 1006138. “Frazers’s Razor: The Ethnology of a Common Object”. . . . . . . . James P. Ronda 1014

I. Medical:139. “A Medical Mystery at Fort Clatsop”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . E. G. Chuinard 1018140. “The Blood Meal: Mosquitoes and Agues on the

Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert R. Hunt 1022

Index to Volume Two. . . . . . . . . .

VOLUME THREE

VI.Journals, Letters and Related Early Writings

Introduction to Section VI . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1037

141. “The ‘Writingest’ Explorers of Their Time: New Estimates of theNumber of Words in the PublishedJournal of L&C Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Robert B. Betts 1038

142. “Meriwether Lewis’s ‘Colouring of Events’” . . . . . . . . . . . .Paul Russell Cutright 1049143. “‘we commenced writing &c.’ A Salute to the Ingenious

Spelling and Grammar of William Clark.”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert B. Betts 1069144. “Writing in Clover: The Versatile

Vocabulary of Lewis and Clark”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 1074

Contents

xv

145. “Battery of Venus: Clue to the Journal-KeepingMethods of Lewis and Clark”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Thomas W. Dunlay 1078

146. “The Journal of Captain Meriwether Lewis (SomeObservations Concerning the JournalHiatuses of Captain Lewis”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Paul Russell Curtright 1083

147. “The Role of the Gass Journal”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Carol Lynn MacGregor 1090148. “The Biddle-Clark Interview”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 1098149. “The Lost Vocabularies of the

Lewis and Clark Expedition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert A. Saindon 1101150. “The Journals of the Lewis and Clark

Expedition: Beginning Again”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Gary E. Moulton 1107151. “An 1894 Monograph about Sergeant Floyd’s Journal”. . . . . . . Robert E. Lange 1114152. “Elliott Coues on Lewis and Clark: A Discovery” . . . . . . . . . . . . .George Tweney 1120153. “New Documents of Meriwether Lewis” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Gary E. Moulton 1125154. “‘I wish you to see and know all’ The Recently Discovered

Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark”. . . . . . . . . . .James J. Holmberg 1131155. “The ‘New’ William Clark Letters” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .James J. Holmberg 1145156. “‘The Report Has Vexed Me a Little’—William Clark

Reports on an Affair of Honor”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . James J. Holmberg 1152157. “Literary Borrowings from Lewis and Clark” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 1156

VII.Immediately Following the Expedition

Introduction to Section VII . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1164

Fur Trade158. “Expansion of the Fur Trade Following

Lewis and Clark” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Charles E. Hanson, Jr. 1165

Telling the Story159. “Expedition Aftermath: The Jawbone Journals”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 1171

Persons—Meriwether Lewis160. “Meriwether Lewis Comes Home”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Donald Jackson 1181161. “Conflict! Frederick Bates and Meriwether Lewis” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Ruth Frick 1184162. “Lewis and Clark: Master Masons”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Eldon. G. Chuinard 1190163. “Rest, Rest, Perturbed Spirit (About the Death

of Meriwether Lewis)”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Paul Russell Cutright 1193164. “How Did Meriwether Lewis Die? It Was Murder.” . . . . . . . . Eldon G. Chuinard 1213•Boxed Feature: “Lewis and Clark are not Alone”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Dwight Garrison 1237165. “‘A Fatal Rendezvous’: The Mysterious

Death of Meriwether Lewis” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .John D.W. Guice 1238—William Clark166. “Fincastle-Santillane and William and Judith Clark”. . . . . . . . Eldon G. Chuinard 1253167. “Captain Clark’s Belated Bonus” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 1259—Zebulon Pike168. “Zebulon Pike: The Poor Man’s Lewis and Clark”. . . . . . . . . . . .Donald Jackson 1264

Contents

xvi

—Alexander Von Humbolt169. “The Humbolt Connection” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 1271

Events170. “St. Louis Welcomes and Toasts the Lewis and Clark Expedition:

A Newly Discovered Newspaper Account” . . . . . . . . . . . . . James P. Ronda 1279

VIII.Lewis and Clark Trail Sites

Introduction to Section VIII. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1282

Archaeological Work171. “Searching for the Invisible: Some Efforts to Find

Expedition Campsites”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Kenneth Karsmizki 1283•Editorial: “Folklore versus Archaeological fact”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1305172. “Nez Perce Claim to have Lewis and Clark Arifacts” . . . . . . . Robert A. Saindon 1306

Old Trail Revisited173. “Colonel Gibbon Tracks Lewis and Clark”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 1310174. “Old Map Helps Pinpoint Location of Original Fort Clatsop”. . .Marty Erickson 1316175. “The Rediscovery of Clark’s Point of View”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Glen Kirkpatrick 1319176. “We Encamped by Some Beautifull Springs—An Interpretation of

Captain Clark’s Campsite of July 7, 1806”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . .Anna Loge 1325

IX.Commemorations, Interpretations, and Depositories

Introduction to Section IX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1335

Events177. “We Met Them at the Fair: Lewis and Clark Commemorated at the 1904

Louisiana Purchase Exposition”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ann Rogers 1336Geography

178. “Montana’s Mystery Mountains” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arlen J. Large 1346

Reflections and Interpretations179. “The ‘Core’ of Discovery” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .James P. Ronda 1353180. “Voyage of Discovery: Lewis and Clark Expedition,

Lewis and Clark College. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .James A. Gardner 1360181. “Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and the

Discovery of Montana”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Harry W. Fritz 1370182. “The Clark/Sacagawea Affair: A Literary Evolution”. . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 1378183. “The Corps of Discovery: A Roaring good Story”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . Dan Murphy 1384184. “The Chimneys of Fort Mandan. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Dayton Duncan 1388185. “What the Lewis and Clark Means to America”. . . . . . . . . . . . . .Dayton Duncan

Contents

xvii

1397186. “Meriwether Lewis’s Curious Adventure”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Dayton Duncan1407187. “. . .one smal trout” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Wilbur P. Werner 1414

Depositories of Lewis and Clark Materials188. “Lewis and Clark in New England: Memorabilia at the Peabody

Museum, Boston Atheneum, and Bienecke Library”. . . . . . . . .Walter Marx 1418189. “New Treasures in Old Depositories (Philadelphia)” . . . . . . . . . . . .Frank Muhly 1424190. “Lewis and Clark and the Filson Club”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . William P. Sherman 1430

X.Some Prominent Lewis and Clark Scholars

Introduction to Section X. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1432

Nicholas Biddle191. “History’s Two Nicholas Biddles”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 1433

Olin Wheeler192. “Lewis and Clark Historian: Olin D. Wheeler”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Robert E. Lange 1443

Elijah Harry Criswell193. “Dr. Elijah Harry Criswell (1888-1967)”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Paul Russell Cutright 1446

Bernard DeVoto194. “Bernard DeVoto and His ‘Struggle of Empires’” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Arlen J. Large 1449

Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1458 Index to Volume Three

Contents

xviii

Illustrations

Volume I

1. William Clark’s 1810 map as it was engraved for reproductionto accompany the 1814 official narrative ofthe Lewis and Clark Expedition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .pocket inside back cover of vol. I

2. Portraits of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark by Charles Willson Peale . . . . frontispiece3. A detail of Captain George Vancouver’s Map of the Pacific

Northwest (published in 1798) showing the mouth of theColumbia River and adjacent mountains. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

4. Sir Alexander Mackenzie’s Map of western Canada published in 1801. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105. Sir Alexander Mackenzie’s 1793 Route to the Pacific. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .276. Map of the voyage of Laperouse. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 517. Portion of David Thompson’s map showing the “Road to the

British Establishments” from the Mandan/Hidatsa trade center. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 618. Facsimile pages from Executive Journal showing vote on appropriation

for L&C Expedition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 929. Code for secret messages between Meriwether Lewis and President Jefferson . . . . . . . 9910. Silhouette of Meriwether Lewis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10511. Pencil sketch of Locust Hill, childhood home of Meriwether Lewis. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10512. Key to the coded rating of Army officers used by Meriwether Lewis. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11613. Facsimile of clipping from National Intelligencer listing Lewis

on Board of Agriculture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12014. 1803 view of the U.S. Capitol building . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12315. Location map of Harpers Ferry in 1803. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12716. The Point and Large Arsenal at Harpers Ferry c. 1803 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12817. U.S. Geological Survey map showing Clark property in Virginia. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14818. Map showing Ben Tompkin’s estate, adjacent to the Clark grant of 1730. . . . . . . . . . . . 14919. Virginia Historical marker for William Clark’s birthplace. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15120. Map showing John and Anna Rogers Clark’s property in Spotsylvania County. . . . . 15221. Facsimile of President Jefferson’s letter of credit given to Meriwether Lewis . . . . . . . 16822. Clark’s map of the Grand Tower area of the Mississippi River . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17323. Wood River Camp by Artist Ruth Means. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20224. Map showing original (1808) Wood River Township Survey. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20525. Comparison Map showing Wood River area in 1804 and 1970. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20626. Artist George Catlin’s 1832 drawing of Floyd’s Bluff . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24927. Photo showing vicinity of Sergeant Floyd’s grave. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26128. Photo of workmen “pointing up” the apex of Sergeant Floyd’s monument . . . . . . . . . 26529. Photo of people in attendance at the 1901 unveiling of Sergeant Floyd’s monument. . 26630. Ambrotype of Patrick Gass. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27231. A reproduction of a small photo of Patrick Gass. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27232. A photo of a portrait of Patrick Gass. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27233. Photo of Robert Gass holding a photo or Patrick Gass. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27334. Photo of a large tinted photo of Patrick Gass when he was in his nineties. . . . . . . . . . . 27535. A portrait painting made in Patrick Gass’s later years. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27636. Portrait of Patrick Gass taken from a daguerreotype when he was nearly ninety-nine. . 277

xix

Illustrations

37. Photo of Patrick Gass’s folding lorgnette . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27838. Photo of Annie Jane Gass Smith daughter of Patrick Gass. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .27839. Inscription on the face of William Bratton monument . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29140. Detail of Clark’s 1809–1810 map showing John Colter’s post-Expedition journey. . . .29941. Township map from 1878 Atlas of Franklin Co., MO. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30842. 1984 map showing survey No. 975, Franklin Co., MO. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30943. Karl Bodmer’s painting with the possible likeness of Toussaint Charbonneau. . . . . . .35244. Clark’s map showing overland trail from Mandan/Hidatsa

villages to the Yellowstone River . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .387

Volume II

45. Eulachon drawn by William Clark. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . frontispiece46. Heads of Clatsop Indians drawn by William Clark . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . x47. Ancient mummy of a elfin-like creature found in the Pryor Mountains of Wyoming. .48048. Map showing Mandan and Hidatsa village sites . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48249. Modern map showing locations of Hidatsa villages on Knife River . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48550. Sitting Rabbits drawing of the Hidatsa village where Sacagawea

and Charbonneau resided . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48651. Aerial view of Sakakawea Village Site. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .48752. Facsimile of quadruped drawn by Clark on his map for May 29, 1805. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50553. Detail of U.S. Geological Survey map showing the mouth of Arrow Creek . . . . . . . . . .50654. Detail of Clark’s 1805 map showing mouth of Arrow Creek. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50755. Modern map showing Lewis and Clark’s Great Falls Portage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .51256. Map showing western end of Lewis and Clark Trail. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53457. Clark’s drawing of a U.S. flagon the keelboat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .55458. Illustration showing an example of a spontoon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56859. American spontoon blade (circa. 1750–1760) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .56960. “Espontoon” blade drawn by Lewis at Fort Mandan. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57061. American spontoon blade (circa. 1770–1780) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .57062. Spontoon axe of the type Lewis described at Fort Mandan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .57063. Detail of a photo of the statue “Explorers at the Portage”

showing Lewis with his “espontoon”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57164. Drawing of sextant with description of its parts. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57765. Equatorial Theodolite . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57866. Clark’s drawing of the side view of Lewis’s keelboat. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .62867. Clark’s top-view drawing of White Pirogue indicating its eight-ton capacity. . . . . . . . 63068. Three views of the White Pirogue—conjectural drawing by Robert Saindon. . . . . . . . .63069. Top view of Lewis’s keelboat as drawn by Captain Clark. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .63570. “Stave Winder” for wrapping fishing line. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67271. “Stave reel” drawn by Chris Partington perhaps like Lewis used when fishing. . . . . . 67272. Moccasins belonging to Meriwether Lewis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73973. Illustration of Private, First Infantry uniform about 1803. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76074. Illustration of what Sergeant John Ordway’s uniform would have looked like. . . . . . . 76075. Illustration of a “tent of cover” used by troops on the march. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77176. Dance Music for Cruzatte’s fiddle. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .794

xx

77. Reproduction of a drawing of the ragged robin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82878. Digging stick used by the natives for digging roots. . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83479. Map showing location and number of buffalo killed by the L&C Expedition. . . . . . . . 87480. Head of a gull, drawn by Captain Clark. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88181. Head of brant, drawn by Captain Clark. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88182. Head of Vulture (Condor) drawn by Captain Clark. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .88283. Cock of the Plains, drawn by Captain Clark. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88384. Lewis’s Woodpecker and Clark’s Nutcracker. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90585. Mountain quail drawing by C.W. Peale. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91586. Western tanager drawing by C.W. Peale. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91587. Lewis woodpecker drawing by C.W. Peale . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91588. John Evans’s 1796–1797 map showing Mandan and Hidatsa villages. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94189. Page from the British Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris. . . . . . . . . . . .95690. Segment Reproduced from Lewis’s Weather Diary for December 1804. . . . . . . . . . . . . 97491. Engraving of Lewis wearing a tippet given to him by Cameahwait. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99692. Four-stick game of Klamath Indians. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101293. Netted hoop for the hoop and arrow game. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1013

Volume III

94. White Salmon Trout drawing by William Clark. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . frontispiece95. First page of Joseph Whitehouse’s journal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . x96. Front and reverse of Lewis’s herbarium label for the honeysuckle. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112797. Promissory note of Meriwether Lewis written Sept. 27, 1809. . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . .112898. Facsimile of Julia Hancock’s signature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125599. Facsimile of George Hancock’s certificate of assent for his

daughter to marry William Clark. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1255100. Marriage certificate of William Clark and Julia Hancock. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1256101. Caywood’s exploratory Excavation of Fort Clatsop . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1287102. Lewis and Clark’s map of Wood River vicinity. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1293103. Possible 1804–1805 Fort Mandan with Missouri River channel 1881 and 1981. . . . . .1296104. Clark’s map of the area about the Great Falls of the Missouri. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1305105. Nez Perce hat and Lewis and Clark adz. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1307106. Lewis and Clark axe head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1308107. Nez Perce elk horn wedge scarred by Lewis and Clark party . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1308108. Lewis’s saddle found by the Nez Perce. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1308109. Lewis and Clark powder measurer given to Nez Perce. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1309110. 1851 map of U.S. Coast Survey showing Fort Clatsop as “log hut”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1318111. Auction catalog cover and page five describing Lewis’s airgun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1427

xxiii

Editorial Procedures

How should one proceed in presenting scholarly research to both the scholarand the common reader? The Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, althoughacademically sound, is not a professional association. It is made up of people fromall walks of life who are (as the great Lewis and Clark historian Elliott Coues describedhimself) Lewis and Clark enthusiasts. And so, the articles found in We ProceededOn, the Foundation’s quarterly, although scholarly researched by professionals andstudents alike, were written with the common Lewis and Clark enthusiast in mine. Itwas, therefore the role of the editor of the present work to maintain some sort ofeditorial balance in presenting the articles to the general public. It was a conundrumof sorts in attempting to fix on a style that would please the scholars, the enthusiasts,and the general public.

My charge with this project was somewhat simple: present to the reader thefeature articles of the past twenty-five volumes of We Proceeded On. Presentfacts without embellishment, prose without flair—write for the people not the Pulitzer.

As it is the writer’s role to be faithful to his subject matter, it is the editor’s roleto be faithful in presenting the writer’s material to readers. In attempting to befaithful to my readers, I have at times been rather critical of the writer’s presentationof certain information. When I found it difficult to understand I attempted to clarifyit; when I found it incorrect I tried to correct it; when I thought another opinionshould be expressed, I expressed it; when I found a statement that didn’t makesense to me, I noted it; and when I found statements illogical to me, I pointed themout. I respect all of the authors whose work appears on the pages that follow, and Ido not pretend that in being critical of certain aspects of their work that I have anysuperior knowledge of their subject matter. As editor I have felt an obligation toassist my readers through the material presented. In the final analysis, it will be myremarks that are subject to critical review.

The Latin abbreviations and phrases so common in academic referencing andfootnoting is antique to the common reader and therefore were, for the most part,eliminated. Likewise, other abbreviations and symbols common in certain literarycircles have been kept to a minimum.

To facilitate the reading of the articles, the sources and notes were placed atthe bottoms of the pages to which they refer, rather than at the end of each article,section, or at the end of the work itself.

In an anthology of articles as closely related in subject matter as the onespresented here, it is understandable that certain sources will be repeated many

xxiv

Editorial Procedures

times. Because of that, it was decided that references would be tied to the bibliographyso that title, publisher, city, and date would not have to be repeated every time it wasused by the various authors. Thus, only the author and page numbers were placed atthe bottom of the page along with the supplementary notes. If multiple sources areattributed to one author, they are identified by a numeral in parenthesis. For example,a footnote appearing as “Jackson, Donald (3), p. 36” would refer to the third workof Donald Jackson found in the bibliography, thus, Thomas Jefferson and the StonyMountains, page 36.

Books, magazine articles, newspaper articles, manuscripts, maps, etc. are notseparated into categories in the bibliography. Sources (whether book, magazine article,etc.) were simply listed under the appropriate author’s names in the order theyarose in the editing process.

I have tried to edit all articles so that they conform with regard to the spellingsof the names of persons, places, and things, however, I have usually left the variationsof those spellings when found within quotation marks. The following spellings of thenames of Indian tribes were used—while at the same time being aware of otheracceptable spellings: Blackfeet (rather than Blackfoot), Assiniboine (rather thanAssiniboin), Shoshone (rather than Shoshoni), Minnetari (rather than Minnetaree). Ihave also clarified where necessary the difference between the Minnetari of theMissouri River (Hidatsa, Big Bellies, Gros Ventre), the and Minnetari of the Prairie(Atsina, Big Bellies, Gros Ventre de Prairie).

The name of the Expedition’s 1803–1804 winter camp on the Illinois side ofthe Mississippi at the mouth of the Missouri River takes on several variations. As amatter of clarity I have attempted to edit all references to it as Wood River Camp(rather than Camp Wood, Camp Wood River, Camp Dubois, Dubois Camp, etc.).

By his own hand we now know that it’s Private Robert Frazer (rather thatFrazier). Drouillard (rather than Drewyer)—for the civilian interpreter hired at thebeginning of the Expedition. Sacagawea is used rather than Sacajawea, as that’s theclosest approximation of her name as most commonly spelled by Lewis and Clark.

There has been new research, insights, and discoveries since some of thearticles were written. In many cases I have brought information within the articlesup to date using editor’s notes placed at the bottom of the page among the referencesand notes of the author. Occasionally I have stated my opinion in the “editor’s notes.”Hopefully they can be distinguished from evidentiary information.

When stumped for a plausible way to handle a certain editorial procedure Ireferred to the Chicago Manual of Style, thirteenth edition.

The articles presented here were not written as so many pieces of a jigsawpuzzle that would one day be put together by some knowing editor. They were,instead, independent essays, each written with the intention of standing by itself.Therefore it may be a bit deceiving for the reader to see them in categories as Ihave placed them for this work. The uninformed might expect that they would flowtogether better. But in understanding their origin one also begins to understand therepetition of the inter-essay information. For example one is informed in many of the

xxv

Editorial Procedures

essays that Meriwether Lewis had been the secretary to President Jefferson—yetno article herein deals exclusively with that issue. It is, therefore, understandablethat so many independent articles dealing with various aspects of the Lewis andClark Expedition, written over a period of twenty-five years would repeatinformation. At the onset of this editorial project it was hoped that I would stumbleonto a way of eliminating some of the repetition, but every attempt jeopardized theintegrity of the article from which I tried to lighten the burden. But these are essaysand not chapters in a novel. They hang together in that they are explorations intothe world of Lewis and Clark. They deal with aspects of the Lewis and ClarkExpedition, but remain independent essays.

Due to the intent of the essayists, it also follows that certain information withinan essay does not necessarily follow the chronological order in which I have chosento categorize it.

Each article presented in this work has been painstakingly researched. Thewhole, therefore, constitutes a wealth of information for future researchers of theLewis and Clark enterprise. But it has been my effort to go beyond presenting ananthology of scholarly articles that would otherwise be found only in the referencerooms of university libraries. This is scholarship presented for the scholar andcommon reader alike. Here, nearly 200 articles on various aspects of the Lewis andClark Expedition, written over a twenty-five-year period of time, have beencategorized into ten meaningful sections with some attention to chronological order.Thus, I have attempted to prepare for both the common reader and the scholar atrustworthy, well-referenced, easy-reader on the epic journey of Lewis and Clark.

Compiling such an impressive anthology of articles written by over sixtycompetent writers whose work had already been handled by at least three editorsusing various editing styles has made the present literary endeavor a challenge. Ithas been my job to decide on a standard spelling for the many words that have morethan one acceptable spelling; to be consistent in the use of one name for thosepersons, places, and things that have more than one acceptable name; to devise atable of contents that breaks the subject matter down to facilitate the use of thematerial; to present a comprehensive bibliography; and to determine a method ofreferencing and footnoting that would be functional without being overly cumbersome;and to include a comprehensive index.

It is my hope that in presenting to the reader the feature articles of WeProceeded On in the present format that I have not dragged the work of others intothat black abyss where no scholar, nor student, nor common reader abide.

xxvi

Preface/Acknowledgments

The Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc., was established in 1969as a successor of the Lewis and Clark Trail Commission which had been establishedby an act of Congress dated October 6, 1964. By encouraging dialogue and promotingcooperation and long-range planning, the Commission achieved a new sense ofpurpose and unity among the states traversed by the exploring party. The Commissionexpired in 1969, and in its final report to the president and Congress its membersindicated that an assignment of the nature given to them is never completed. It was,therefore, out of the Commission’s recommendations that the Foundation came tobe. The Governor of Missouri suggested to the Governors of the eleven Trail Statesthat each appoint a State Lewis and Clark Trail organization to coordinate Lewisand Clark activities in each Trail State. Thus, in the beginning the Lewis and ClarkTrail Heritage Foundation was, in essence, a federation of the eleven Trail Statesorganizations. It was incorporated under the “Not for Profit Corporation Act” of theState of Missouri. Although the Foundation embraces many state Lewis and Clarkorganizations and has many chapters across the country it is not considered afederation of state entities as it had been at inception.

The Foundation was given “seed monies” from the Lorene Sales HigginsCharitable Trust of Portland, Oregon, for the purpose of establishing a publication,and for several years continued contributions which enabled the Foundation’s quarterly,We Proceeded On, to take root.

The magazine was established in 1974 under the able editorship of the lateRobert E. Lange who, by his own description, was a Lewis and Clark purist. He setthe standard for the scholarship of We Proceeded On and other special publications.For over twelve years he continued as editor, and the magazine earned a reputationfor excellence in the field of Lewis and Clark study.

In 1976, the Foundation set up an endowment for its publication through thesale of a limited edition bronze created by world famous sculptor Bob Scriver. Acompanion bronze was created by Scriver in 1986 for the same purpose. The incomefrom these sales, as well as further contributions to the We Proceeded OnEndowment over the years have allowed the Foundation to enhance the presentationof its scholarly Lewis and Clark writings.

The Foundation is not a professional organization, nevertheless it is repletewith professionals from many fields. They, as well as the non-professionals, whotogether make up the membership are all “Lewis and Clark enthusiasts.” Amongthe members are trained historians, doctors, lawyers, scientists, professors, and lay

xxvii

people. From these people have come the articles found on the pages of WeProceeded On. Each contribution is an exploration down an avenue in the world ofLewis and Clark. And his or her research gives us new light on an aspect of theLewis and Clark Expedition. It is within these essays that we begin to fully understandwhat is presented on the pages of the Expedition journals.

The essays give depth to the journals, reveal what the journals fail to say,identify what the journals fail to identify, clarify where the journals are ambiguous,give flesh to the names, give proper recognition where recognition is due, identifythe accomplishments, and above all enlighten the reader on the pre-eminence of theLewis and Clark Expedition in the history of exploration.

Over a period of several years former Foundation president Don Nell ofBozeman, Montana, worked diligently to get the feature articles of We ProceededOn, properly released from the many authors, sorted, compiled, edited, and formattedfor re-publication, and to find an editor to meet the challenge. He is truly the forcebehind getting this publication to press, and his contributions cannot go unrecognized.Former Foundation president John Montague of Portland, Oregon, spent long hoursworking on the project especially scanning pages from the magazine in preparationfor the editing. Former Foundation president David Borlaug, of Washburn, NorthDakota, was of great help to me on many occasions, and Foundation PublicationsCommittee chairman Jim Holmberg of Louisville, Kentucky, was always there tooffer me encouragement and support. Of greatest assistance on the project was thetedious task of my capable friend Robert K. Doerk of Fort Benton, Montana, whoso generously and cheerfully performed the onerous task of proofreading all threevolumes. In addition to his proofreading, Bob made corrections and suggestions thathave contributed significantly to the importance of this literary undertaking.

Obviously, a project of this size requires the assistance of many more thanthose just mentioned. It is doubtful that an attempt to identify them all would besuccessful. Therefore let me simply thank the authors who have so generouslycontributed their writings and allowed them to be republished here. An attempt wasmade to get updated information for the biographical sketches that accompany thearticles, but many remain as they were at the time the articles were first published.To those whose biographies were not updated, I apologize.

R.A.S.Fort Peck Indian Reservation

February 2000

Preface/Acknowledgment

xxviii

General Introduction*

It is commonly understood that it was the genius of Thomas Jefferson thatwas behind the famous Lewis and Clark Expedition—“the author of our

enterprize,” as Captain Clark put it. His mark illuminates figuratively on theExpedition’s journal pages no less boldly than John Hancock’s mark illuminatesliterally on the Declaration of Independence. To view the Lewis and Clark Expeditionwithout seeing the great Mr. Jefferson at the center of the scene would distort thetrue historic picture.

The Expedition was not merely a product of the Age of Enlightenment (“TheAge of Reason,” as Thomas Paine chose to describe it). Exploration of its kind, atleast in part, had been going on for centuries. From its inception it was to be adiplomatic, geopolitical, commercial, and scientific endeavor. In combination withthe commercial aspect—the furs, agricultural prospects, and the minerals of theterritory—there was to be a quest for the legendary northwest passage that wouldtheoretically connect the entire North American continent with the riches of theOrient which had been coveted by Europeans since the time of Marco Polo, overfive hundred years earlier.

The dream of a trans-Mississippi West exploration was not a spur-of-the-moment or even, as most say, a twenty-year-long ambition of Thomas Jefferson. Itwas a lifelong ambition—dating back to his childhood. His father, Peter Jefferson,and Reverend James Maury (who was to become Thomas’s school master) planneda Missouri River expedition when Thomas was yet an infant. Furthermore, Dr.Thomas Walker, the man who was later to become the young Jefferson’s financialguardian, had been the man selected to lead that ill-fated expedition. One can onlysurmise that by osmosis the concept of a Missouri River expedition had permeated

*Note: An introduction to such a detailed and scholarly set of wide-ranging essays must out ofconsideration to space be sketchy and general. What I have attempted to do is to give a briefbackground of events, especially the explorations and political considerations that I believe influencedto some degree Jefferson’s thoughts in designing the Lewis and Clark Expedition. I by no meanspretend that what I have included in this introduction even closely embraces all the influences. Thereare many other explorations and many other political considerations that could have been identified.

—R.A.S.

xxix

Introduction

the genes, the brain, and the very soul of Thomas Jefferson several decades beforehe ever became president of the United States. But it was the presidency and all itsramifications that had more to do with scratching Jefferson’s itch to learn what wasbeyond the Mississippi than any of the other events that had taken place over thefifty years in which he had been fascinated by the possibility of exploring the West.Over those many years the dream of a northwest passage to the Pacific remainedcentered on the viability of the Missouri River.

DISCOVERY OF THE MISSOURI RIVER

One hundred twenty-nine years before the birth of Thomas Jefferson, CountLouis de Frontenac, governor of New France sent out an expedition of seven menunder the leadership of Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette to explore theMississippi River, and to determine if that river flowed into the Pacific Ocean. Itwas on this expedition (1672) that the mouth of the Missouri River was discoveredby white men. However, to the dismay of all, it was found that not only did theMississippi simply flow into the Gulf of Mexico, it also flowed into Spanish territory.(Hernando DeSoto claimed the land and discovered the Mississippi River in 1541 inhis ruthless yet fruitless search for gold, journeying across the lands between thepresent states of Florida and Oklahoma.) It was nearly fifty years after Jolliet andMarquette descended the Mississippi (1720) and discovered the Missouri River thatFather Pierre Charlevoix came upon the idea that the Missouri might eventuallyserve as the conduit to a northwest passage to the Pacific.

About this same time the English were also developing ideas on a water routeto the fabled northwest passage. As early as 1727 Daniel Coxe theorized that theMissouri provided a transportation route that would require only a short portage tothe waters of the Pacific.

The French continued their efforts to find the passage, and in 1738 the bravePierre Gaultier de Varennes de la Verendrye and his sons, crossed into westernCanada and beyond Lake Winnipeg, and eventually southward, to be the first whitemen to reach the upper waters of the Missouri. However, when the youngerVerendryes later continued beyond the Mandans they did not follow the MissouriRiver in their quest for the fabled northwest passage, instead they crossed that rivernear the Mandan villages in present central North Dakota and headed west, but tono avail.

As the Verendrye were coming across North America from the east on behalfof New France, Russian ships were beginning to cross the Bering Strait and comingdown the Northwest coast.

DISCOVERY OF THE PACIFIC OCEAN

But the story of a passage across America to the Pacific goes back muchfurther. As early as 1513 the Spanish explorer Vasco Nunez de Balboa had made atrek across the isthmus of Panama and had ambitiously taken possession of thePacific Ocean in the name of the Spanish Monarch. From that time the Spanish had

xxx

Introduction

moved north along the western coast of the North American Continent, had exploredinland, and had conversed with many Indian tribes.

In 1576 Sir Martin Frobisher traveled the Canadian Arctic in search of anorthwest passage. Thirty-four years later Henry Hudson attempted to discover anorthwest passage but found only the Hudson River.

THE EARLY YEARS OF THOMAS JEFFERSON

It was at the time the Verendryes were searching for the Northwest Passagethat Thomas Jefferson was born (1743) in the English colony of Virginia at Shadwell.His father, Peter, was a surveyor who had moved from the coastal settlementstoward the frontier. Thomas started school when he was five, and entered boardingschool at the age of nine.

It was during these early years of Thomas’s life that his father was planning anexploration of the Missouri River in an attempt to find the northwest passage. WhenThomas was fourteen his father died. At that time Dr. Thomas Walker, a closefriend of Peter Jefferson, and the man who was to lead the proposed expedition upthe Missouri, became the financial guardian of the Jefferson children. At this timeThomas was sent to classical school with Reverend James Maury as his master. Itwas Reverend Maury and Peter Jefferson who had been the masterminds of theMissouri River expedition. One can only imagine that the subject of the MissouriRiver expedition came up in class more than once during Thomas Jefferson’s threeyears of tutelage from Reverend Maury.

Jefferson entered college in 1761, and even though he was a revolutionist asearly as his college years, he continued to be influenced by English thought withregard to the developing concept of a northwest passage. In 1727, as noted above,it had been theorized that in less than half a day a party could cross a “ridge of hills”between the Missouri and navigable waters leading to the Pacific. During his visit tothe present Wisconsin/Minnesota area forty years later, Jonathan Carver renewed thatold British idea that the Missouri River provided the practical route to the Pacific.

FRANCE SECRETLY CEDES LOUISIANA TO SPAIN

To help set the geopolitical stage for the Lewis and Clark Expedition it shouldbe interjected at this point that prior to 1762 France had claimed Louisiana, thewestern watershed of the Mississippi River which included the entire Missouri Riversystem. But with the upcoming (1763) Peace of Paris which would end the SevenYears War (during which France had lost an empire) there was a fear that GreatBritain would claim Louisiana. Therefore, in 1762 France secretly ceded Louisianato Spain. Great Britain received the whole of Canada and various islands of theWest Indies.

At the time Jefferson was elected to the Virginia legislature (1769) the Spanish,on the west coast, were beginning to build missions and military presidios beginningat San Diego. Spanish ships were being sent north to assess the Russian attempts togain footholds along the western coast of North America.

xxxi

By 1772 the British slightly revised their theory about the northwest passageand now hypothesized that there was a twenty-mile portage from navigable watersof the Missouri to navigable waters of the Oregon River (a legendary river yetundiscovered that was thought to be the western waterway of the northwest passageto the Pacific.)

Jefferson’s writings just prior to the Lewis and Clark Expedition indicate thathe had adopted the earlier British hypothesis that the portage over “a ridge of hills”to the “Oregon River” would be less than half a day. This fallacious concept ofwestern geography, which dated from 1727, was perhaps the speculation upon whichPeter Jefferson and Reverend James Maury had based their planned Missouri Riverexpedition, and therefore the one Thomas Jefferson had harbored over the years

Jefferson was a collector of maps as well as any other new informationdiscovered by expeditions in the West. The Oregon River was not being found, eventhough the Spanish had explored the present Oregon coast since as early as 1543.From that date many sea captains probed the coast looking for the legendary riverthat would provide a water passage across the continent.

A Spaniard named Captain Bruno Hezeta did sight the estuary of the Columbiain 1775, but was discouraged by the sandbar that sealed the mouth of the river.Thirteen years later Captain John Meares, a British merchant investigated Hezeta’sclaim and declared that no such river existed. In two hundred forty years of searchingthe Pacific coast of North America an estuary had been seen, but the practicable“Oregon River” had not been found. Under those circumstances it would probablynot have been prudent for a wise man of the late 1770s to continue developing ideasabout an Oregon River/northwest passage.

THE DYNAMIC LIFE OF THOMAS JEFFERSON

The American Philosophical Society, with worldwide membership of the mostingenious and curious men of the day, had been formed in Philadelphia in 1746—three years after Jefferson was born. By 1781 the brilliant and already famousJefferson was serving as counsellor of that learned institution.

Jefferson lived a very active political life. He was elected to the VirginiaLegislature in 1769, where he served until the Revolution; he was a member of the1774 and 1775 Virginia Conventions; he was a delegate to the Continental Congressin both 1775 and 1776, during which he wrote the Declaration of Independence; hereentered the Virginian House of Delegates in 1776; and was elected governor ofVirginia in 1779.

Three points should be noted here with regard to Jefferson’s election as governorof Virginia. 1.) The Revolutionary War was still going on; 2.) Virginia extended tothe Mississippi River; and 3.) The hero of the War in western Virginia was GeorgeRogers Clark.

It is also important to understand that at the time Jefferson was elected governorof Virginia there was already a good deal of activity going on in western Canada bythe British fur companies, and at that same time they were coming down into the

Introduction

xxxii

Spanish-owned Louisiana Territory and frequenting the Mandan/Hidatsa trade centeron the Upper Missouri River, 1609 river miles above St. Louis. At that early date, aFrench free-trader by the name of Menard (a former North West Company employee)was already living at an Hidatsa village. The North American Continent wasfiguratively shrinking.

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK AND A PLAN TO EXPLORE THE TRANS-MISSISSIPPI WEST

Jefferson briefly retired from public life in 1781, but was soon back again as amember of the Continental Congress, and was still Counsellor of the AmericanPhilosophical Society. It was while a member of these two august bodies thatJefferson penned a letter to George Rogers Clark with a plan to explore the trans-Mississippi West. But the plan did not specifically address the universal and perennialdesire to find a northwest passage to the Pacific. The existence of that enigmaticroute had probably become doubtful by this time. Instead, Jefferson was motivatedby a more immediate revelation. He wrote: “I find they [the British] have subscribeda very large sum of money in England for exploring the country from the Mississippito California. . .Some of us have been talking here in a feeble way of making theattempt to search that country. . .How would you like to lead such a party?”

This proposal was presented in the light of political considerations: the politicsof Virginia ceding her western lands to the confederation, the acquisition of the(Old) Northwest Territory, and Jefferson’s report On Government for the WesternTerritory. By the Paris Treaty of 1783, the British had given up their claim to landsdirectly east of the Mississippi, and were now looking to explore the trans-MississippiWest. Jefferson surmised that their intent was to establish settlements there. Congresswas concerned about the republic’s interests all the way to the Mississippi River, butsome were even looking beyond that western boundary. Those who were talkingwith Jefferson in a “feeble way” about matters beyond the Mississippi were nodoubt fellow congressmen—more so than members of the American PhilosophicalSociety—at least George Rogers Clark understood that those speaking with Jeffersonabout the trans-Mississippi West were congressmen.

From Jefferson’s request, and Clark’s response, it would seem that, unlike thegenerous British subscription, there were no funds anticipated for any such Americanexploration. Clark had naively spent his own fortune in Revolutionary War battlesfor Virginia and the colonies. And perhaps it was because there was no offer forcompensation that he wrote: “Your proposition respecting a tour to the west andNorthwest of the Continent would be Extreamly agreeable to me could I afford itbut I have lately discovered that I knew nothing of the lucrative policy of the World[,]supposing my duty required every attention and sacrifice to the Publick Interest.”

In declining the offer, Clark went on to explain that a party of only three of fourmen should be used for such an enterprise so as not to alarm the Indians. He alsobelieved that it could be done with a trifling expense, but that the explorers shouldbe amply rewarded upon the successful completion of their venture.

Introduction

xxxiii

MONITORING THE LAPEROUSE EXPEDITION

With the Clark expedition plan aborted, Jefferson sailed to Europe the followingyear where he with John Adams and Benjamin Franklin were to make treaties ofcommerce. In 1785 he was made minister to France. A position he held for fouryears. During his first year as minister, Jefferson became aware of and even spiedupon the activities of the French navigator Jean Laperouse who was setting outfrom Brest to explore the Pacific Basin. It was conjectured from information gatheredby Jefferson’s spy (John Paul Jones) that Laperouse would be establishing tradingposts if not settlements along the northwest coast of North America. In fact, but notknown to Jefferson, the king desired that “. . .when Laperouse should reach theNorthwest Coast of America, he was . . .to study the possibilities for trade, especiallythe chance to export furs to China and. . .‘what convenience may be found for makinga settlement on the Coast.’” Jefferson continued to monitor the progress of Laperouse.

JOHN LEDYARD AND A PLAN TO CROSS NORTH AMERICA WEST TO EAST

It was also during the time Jefferson served as minister to France that he metwith John Ledyard of Connecticut, a man who had accompanied the famous EnglishCaptain James Cook in his explorative voyage of the Northwest Coast of America(1776-1780) in search of the fabled sea passage across North America or elsearound America to the north. Ledyard had plans to start a fur trade business on thenorthwest coast of America, and that was the purpose of his visit to Paris. His furtrade plan failed in Paris, but his meeting with Jefferson had promise. The twodiscussed the possibility of Ledyard walking across Russia, with a couple dogs anda peace pipe, catch a Russian vessel to Nootka Sound, trace down the Northwestcoast to the latitude of the Missouri River, go inland to that river, and make diplomaticadvances with the native tribes encountered. It was believed that Jefferson hadsought and received permission from the Russians for the safe passage of Ledyardacross their country.

Jefferson later seems to have taken credit for the idea for Ledyard’s failedattempt to cross Russia and North America, but in reality he can take credit for onlycertain aspects of the plan since Ledyard had the idea in his mind a couple yearsbefore he met with Jefferson in Paris.

Knowing that Jefferson was trying to monitor the expedition of Laperouse,Ledyard wrote to Jefferson from St. Petersbourg, Russia, informing Jefferson thathe had received word that Laperouse had reached the eastern Siberian peninsula ofKamachatka.

The Laperouse expedition, however, ended with no French establishment inNorth America, nor did it result in any fur trade on the Northwest Coast. In fact theLaperouse expedition mysteriously ended off the coast of Australia withoutaccomplishing many of it’s stated objectives.

Ledyard’s expedition was even less profitable. Before he could finish his journeyto Kamachatka, the Empress (who, it seems, had not granted permission) had Ledyardarrested, imprisoned in a carriage and deported nonstop to Poland.

Introduction

xxxiv

Thomas Jefferson stayed in France as minister to that country until the fall of1789, when he returned to the United States. He was appointed by PresidentWashington as the country’s first Secretary of State. His duty to keep track offoreign politics and especially geopolitics, must have heightened his concern forUnited States interests west of the Appalachians. Foreign countries continued toprobe the western half of the continent. The farmers west of the Appalachiansdepended on the Mississippi River and the port at New Orleans to market theirgoods. The western lands of the United States were vulnerable to foreign takeover.And the world as a whole actively continued its interest in finding a northwest waterroute across the continent.

As mentioned above, Captain Cook and his men did not find a sea passagethrough North America nor a northwest passage around North America on their1776-1780 expedition. It also appears that the British sponsored no expedition fromthe Mississippi to California as they had proposed in 1783. Instead they turned theirefforts to finding a passage across their own land—above the 49th parallel. In 1789Alexander Mackenzie of the North West Company followed the present-dayMackenzie River to the Arctic Ocean. About that same time the British sent out aCaptain James Knight to find a northwest passage through Hudson’s Bay. Thatexpedition and the fate of its forty-member party ended mysteriously.

SECRETARY OF WAR KNOX PLANS TRANS-MISSISSIPPI EXPEDITION