EVIDENCE OF INNOVATION SYNERGIES...1 EVIDENCE OF INNOVATION SYNERGIES KATHRYN RUDIE HARRIGAN Henry...

Transcript of EVIDENCE OF INNOVATION SYNERGIES...1 EVIDENCE OF INNOVATION SYNERGIES KATHRYN RUDIE HARRIGAN Henry...

1

EVIDENCE OF INNOVATION SYNERGIES

KATHRYN RUDIE HARRIGAN

Henry R. Kravis Professor of Business Leadership

Columbia University, 701 Uris Hall, New York, NY 10027 USA, 001-212-854-3494,

[email protected] [corresponding author]

MARIA CHIARA DI GUARDO

Associate Professor

University of Cagliari, Viale Fra Ignazio 74 – 09123, Cagliari, Italy, 039- 0706753360,

Research assistance was provided by Columbia Business School, with special thanks to Jesse

Garrett, Donggi Ahn, Hongyu Chen, Elona Marku-Gjoka, the Patent Office of the Sardegna Ri-

cerche Scientific Park and Thomson Reuters. The paper benefited from comments from Paul In-

gram, Jerry Kim, Damon Phillips and Evan Rawley.

2

EVIDENCE OF INNOVATION SYNERGIES

ABSTRACT

The content of patents’ backward citations was used to estimate the breadth of diverse

technological learning that was incorporated into each invention. A new patent-score measure

was built that suggested whether post-acquisition innovation synergies had been realized (based

on improvements in firms’ subsequent patent scores). We found that higher performance was

associated with higher backward-citation patent scores and such improvements were associated

with multiplicative innovation synergies. Results also suggested that highly-diversified firms did

not necessarily enjoy the multiplicative, innovation synergies that high backward-citation patent

scores indicated; results indicated that less-broadly diversified firms enjoyed greater multiplica-

tive innovation synergies (as they were defined herein) than did the more-broadly diversified

firms.

1

EVIDENCE OF INNOVATION SYNERGIES

Acquisitions for technology are presumed to increase (or recombine) the knowledge

which the post-integration firm can synthesize within its patentable inventions (Ahuja & Katila,

2001). Evidence is accumulating that the quality of innovations increases thereafter (Cloodt,

Hagedoorn, & Van Kranenburg, 2006; Makri, Hitt, & Lane, 2010; Sears & Hoetker, 2014). It is

not yet clear, however, whether such acquisitions can produce long-term financial performance

improvements for acquiring firms—particularly where an R&D-substitution effect occurs there-

after (Cassiman, Colombo, Garrone, & Veugelers, 2005; Hitt, Hoskisson, Ireland, & Harrison,

1991), but there is evidence that the acquisition of complementary knowledge is valuable—for

several reasons, such as hold-up and pre-emption, as well as for collecting rents through licens-

ing and incorporation in firms’ products (Gimpe & Hussinger, 2014).

We know that organizational learning from technological acquisitions must offer some

novelty in order to stimulate innovation performance (Makri, et al., 2010). We know that explor-

atory innovation processes could synthesize new technologies that move both the acquired and

target firm’s personnel out of their knowledge comfort zones in order to create novel or out-of-

the-box post-acquisition solutions, if they occurred (March, 1991; Rosenkopf, & Nerkar, 2001;

Sorensen & Stuart, 2000). We understand that exploitative innovation processes would rely upon

localized learning processes that built primarily upon the combined firm’s extant competencies,

if they occurred (Kim, Song, & Nerkar, 2012; Lavie, & Rosenkopf, 2006). We do not know the

effects of each type of learning process on firms’ financial performance.

Since innovation activities typically involve both exploitative and exploratory processes

(Andriopoulos, & Lewis, 2009), the relationship between how innovation content is recombined

to create synergies and what post-acquisition performance will be enjoyed by doing so may best

2

be analyzed by examining the component parts of firm’s patented inventions. Because the inter-

nal process of combining diverse knowledge in patented inventions is valuable (Ahuja & Lam-

pert, 2001; Fleming, 2001), we suggest looking at backward-citation patterns to see what techno-

logical knowledge was assimilated in firms’ patents (instead of looking at forward cita-

tions―which have been analyzed extensively to see how firms’ patents have influenced subse-

quent users). We expect that certain patterns of backward patent citations will improve firms’

financial performance―as well as their innovation performance.

The patent which is granted to an invention awards valuable property rights to its inven-

tors (or to their employing firms) which include “the right to exclude others from making, using,

offering for sale, or selling” the invention in the United States or “importing” the invention into

the United States (Department of Commerce, 2013). Specific details bounding an invention’s

property rights are indicated by the technological class codes which are assigned by an examiner

of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) when a patent is granted (which rep-

resents its core knowledge); patents’ rights are sometimes described using a dozen or more sev-

en-digit USPTO classification codes (of which there are over 120,000 in the USPTO coding sys-

tem).

When seeking U.S. patent protection for their inventions, firms cite all germane, previ-

ously-granted patents that have made similar technological claims of novelty; patent examiners

also cite intellectual antecedents of the patent under consideration in order to clarify the novelty

of its contributions. Taken together, this record of backward citations provides information about

how broadly afield knowledge was incorporated into the invention and how similar (or dissimi-

lar) the precedent patents were to the codes of the patent’s grant. (Codes which are different from

those of the patent’s grant represent its non-core knowledge). The similarity and complementari-

3

ty of combined firms’ technological knowledge have been used to predict invention performance

(Ahuja, & Katila, 2001; Cassiman, et al., 2005; Cloodt, et al., 2006; Hagedoorn, & Duysters,

2002; Makri, et al., 2010); we propose to relate the content of firms’ patent antecedents to their

financial performance in this study.

Because synergistic benefits are anticipated when research resources are brought together

after an acquisition, analysis of the nature of post-acquisition synergies may provide insights

concerning how firms’ performance is subsequently enhanced. Like analysis of patents, syner-

gies can be decomposed into consideration of those activities which reinforced the firm’s core

knowledge as well as those activities which stimulated progress into new arenas to expand the

firm’s mastery of non-core technologies (Collins & Porras, 1994). We expect that the stimulus

created by broaching unfamiliar knowledge frontiers will create value for firms’ long-term per-

formance―if they can integrate their acquisitions effectively (Fulgieri & Hodrick, 2006; Paru-

churi, Nerkar, & Hambrick, 2006).

Our additions to what is already known about inventions and patents are fivefold. First,

our study contributes a patent-score measure―that we use to characterize the breadth of techno-

logical knowledge being synthesized in firms’ patents―which has a relationship with firms’

breadth of diversification and return on assets performance. Although our measure is constructed

differently from the “originality” variable posited by Trajtenberg, Henderson, & Jaffe (1997), it

is similar (in spirit) in its use of backward-citation information; moreover, ours is the first empir-

ical test of the relationship between patents’ intellectual antecedents and financial performance.

Second, our patent-score measure can be decomposed into its component parts to track the re-

spective contributions of core and non-core knowledge on performance. Third, our study shows

that inventions containing greater out-of-the-box knowledge content can contribute positively to

4

long-term financial performance. Fourth, our use of the Derwent system for coding technological

knowledge facilitates a more-robust characterization of the intellectual contributions of firms’

inventions than has been offered in earlier patent studies (because all of their awarded patent

codes can be incorporated into our patent-measure calculations). Fifth, our characterization of

synergies as offering additive and multiplicative benefits when resources are combined adds

greater nuance to our understanding about the ease of capturing operating improvements through

the mechanism of synergies.

THEORY AND HYPOTHESES

The Compounding Effects of Synergies

Synergy is the working together of two or more agents (e.g., muscles, drugs or other

forces) so that their combined effect is greater than the sum of their individual efforts (Guralnik,

1970). Eccles, et al. (1999) noted that acquisitions offer the potential to improve firms’ perfor-

mance by reducing costs and enhancing revenues. Cost reduction realizes synergies through

those economies which are based on improving more-familiar activities, e.g., scale,- scope,- ex-

perience,- and vertical-integration (or coordination-) economies; revenue enhancement takes

firms into novel arenas. Although revenue-enhancement synergies may offer greater potential

performance benefits to the firm (by reaching new customers or offering new products to exist-

ing customers), their realization is more ephemeral―just as the exploration activities that are re-

quired to push on the firm’s envelope of product-market positioning activities may not pay off

(Henderson, 1993).

Multiplicative innovation synergies. The former type of synergies—the economic im-

provement of known activities—may be considered to be additive because such activities

strengthen the firm’s extant position (as does increasing its market share through related acquisi-

5

tions). Revenue-enhancement synergies are multiplicative because the combinatorial benefits of

doing something that novel could not have been otherwise accomplished by the post-acquisition

organization had the expertise of the acquirer and target organizations not been integrated—

albeit with the inclusion of some additional organizational learning (Sirower, 1997).

Innovation synergies are most beneficial to firms when the learning gained by combining

researchers’ respective knowledge competencies allows their firm to invent profoundly-novel

solutions for customers’ (Lettl, et al., 2006), which increases customers’ willingness to pay

(which increases the revenues obtainable by commercializing firms’ radical inventions). Expan-

sions in the range of knowledge integrated within the combined firm’s patents are one indication

that innovation synergies have occurred―especially where there is a pattern of more-radical pa-

tent applications being filed after a particular acquisition has been successfully integrated

(Dahlin, et al., 2005; Schoenmaker and Duysters, 2010) since radical innovations affect compe-

tence formation in some relevant way, such as the ability to synthesize inventions across seem-

ingly-unrelated technology fields (Afuah and Bahram, 1995; Schumpeter, 1951; Kogut & Zan-

der, 1992; Tripsas and Gavetti, 2000).

The subsequent granting of new patents to the combined, post-acquisition firm in the ex-

act technological classes which had been sought through a technological acquisition would sug-

gest that the acquiring firm had gained some additional innovation capabilities; indications that

the firm’s new patents were being granted in knowledge cores which the target firm had already

mastered would be additive evidence of innovation synergy. Such combinatorial improvements

in performance can be anticipated and are fully incorporated into the cumulative abnormal re-

turns of the stock market’s reaction (and expectations) associated with the announcement of the

acquisition (McWilliams & Siegel, 1997).

6

It is the unforeseen benefits of combining inventive organizations—improvements that

that market did not already anticipate (and price)—that will stimulate the type of learning which

facilitates radical innovations, creates important gateway patents and forms new ways of using

extant knowledge. Multiplicative synergies arise from potentially-serendipitous interactions

among newly-combined researchers that will facilitate successful stretching beyond an organiza-

tion’s “comfort zone” in mastering the non-core knowledge that is expected to facilitate the radi-

cal organizational learning and knowledge sharing that we argue underlies the realization of mul-

tiplicative innovation synergies.

Multiplicative synergies in patenting. The diversity of patents produced by a highly-

diversified firm (which operates in varied industrial milieus) may be expected to reflect the many

technological streams of knowledge that such firm’s inventors must master. If evidence of inno-

vation synergies is measured simply, e.g., by counting increases in the number of post-

acquisition patents produced or by another additive method, results may primarily reflect the ef-

fects of diversification which are associated with the acquisition. Such measures may not capture

evidence that multiplicative inventive activity has been harnessed. In order to eliminate the pos-

sibility that the diversifying firm has simply added researchers who have exploited their extant

knowledge post acquisition, we argue that what is needed is a measure to account for the simple

combining of resources as typically occurs through diversification―as well as a way to detect

subsequent mastery of new technologies as would occur through successful technology transfer

or knowledge cross-fertilization among the firm’s combined inventors.

The measurement conundrum concerning how innovation synergies are realized is not

trivial because acquisition prices have already included the value of all of the targets’ resources

that were discovered through the due diligence process—as well as the expected effects of their

7

previously-announced investments in new projects. Target firms’ shareholders have already cap-

tured a portion of all previously-known synergies in the acquisition premium that was paid to

them. That is why we look for indications of radical innovation when calculating performance

improvements from combining the acquirer’s and target’s resources. We propose to create such a

patent measure by decomposing a patent’s intellectual antecedents into the core and non-core

knowledge that has been synthesized in order to create the patented invention. Briefly, if the con-

tent of the post-acquisition firm’s patents reflect technological knowledge that is arguably be-

yond its respective combined core areas of knowledge, one might conclude that multiplicative

innovation synergies had been realized and expect that the firm’s financial performance would

increase due to this success.

Hypothesis 1. Backward-citation patent scores indicating that higher proportions

of non-core intellectual antecedents have been synthesized in firms’ inventions

will be associated with higher return on assets performance.

Multiplicative synergies and absorptive capacity. Although we examine the rela-

tionship between success in synthesizing out-of-the-box content within firms’ inventions

and their subsequent financial performance by investigating changes in post-acquisition

patent-score patterns, we know that firms who are most effective at the process of corpo-

rate renewal are already able to assimilate exotic technological knowledge into their own

inventions and see potential applications for their own products in different or unfamiliar

technologies. The researchers within such firms will have developed a greater capacity to

understand the potential uses of others’ novel inventions for their own future innova-

tions―as well as how to share their insights with colleagues to formulate useful (and

8

sometimes disruptive) solutions to customers’ problems (Cockburn & Henderson, 1998;

Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Lichtenthaler, 2009). Because they have well-developed ab-

sorptive capacity, the inventive processes of such firms will constitute a source of com-

petitive advantage (Narasimhan, Rajiv, and Dutta, 2006) which they will to continue to

pursue after making technological acquisitions—in order to gain complementary assets or

otherwise replenish their own stocks of knowledge with the stimulus of new researchers’

insights (Cassiman, et al., 2005; Catozzella & Vivarelli, 2014; Hussinger, 2012). Their

past, high patent-score patterns (representing a fusion of higher non-core technological

content) will persist after their acquisitions have been integrated—as will the expected,

positive performance relationship with their patent scores.

Hypothesis 2a. Acquiring firms that have successfully incorporated higher pro-

portions of non-core intellectual antecedents in their past inventions are more

likely to synthesize higher proportions of non-core intellectual antecedents in the

content of their subsequent, post-acquisition inventions.

Hypothesis 2b. Acquiring firms who synthesize higher proportions of non-core in-

tellectual antecedents in the content of their subsequent, post-acquisition inven-

tions will enjoy positive improvements in post-acquisition return on asset perfor-

mance.

Diversification and Patent Content

Because the breadth of a firm’s line-of-business diversification may be reflected in the

pattern of diverse technological fields which its patents cited when their claims of originality

9

were ultimately granted, diversification strategy could be an alternative explanation for the

changes in patent scores that we expect to see over time. Briefly, because broadly-diversified

firms are exposed to more-diverse bodies of knowledge, such firms might incorporate more high-

ly-diverse ideas into their inventive activity; if that relationship existed, then the backward-

citation scores of their patents should reflect the patterns of their diversification strategy. Broad-

ly-diversified firms who compete in many diverse lines of business would have technological

content in their patents that reflected this breadth of knowledge (Miller, 2004; 2006).

A relationship between breadth of diversification and patent scores is plausible because

we have learned that complementary knowledge is valuable to acquiring firms; the relatedness of

a target firm’s technological knowledge helps the resulting, combined firm’s perfor-

mance―provided that it is not too similar to that of the acquiring firm (Cassiman, et al.,2005;

Grimpe & Hussinger, 2014; Makri, et al., 2010). If target overlap with the acquiring firm’s tech-

nological knowledge is low, Sears & Hoetker (2014) suggest that subsequent inventions may

possess the type of novelty which we classify as being out-of-the-box innovations. Accordingly,

we expected that adding business units which operated in more-diverse lines of business would

increase the proportion of non-core knowledge cited in firms’ patent applications, but that the

relatedness of the combined firm’s diversification posture alone would not predict whether the

post-acquisition synergies enjoyed by their diversification were additive or multiplicative in na-

ture.

The evidence needed to suggest that post-acquisition researchers were creating multipli-

cative innovation synergies through their inventive activities may best be found by analyzing the

content of their patented inventions. Whether such innovation is serendipity or from program-

matic learning processes (Graebner, 2004), we suggest that greater synthesis of non-core

10

knowledge from beyond the firm’s presumed areas of expertise would imply that novel technol-

ogies had been combined fruitfully. We believe that this learning phenomenon may arise inde-

pendent of the content of firms’ diversification strategies and that its presence indicates evidence

of multiplicative innovation synergies.

Hypothesis 3a. Diversified firms will synthesize higher proportions of non-core

intellectual antecedents in the content of their post-acquisition inventions.

Hypothesis 3b. Acquiring firms who most broadly increase their post-acquisition

diversification of the breadth of businesses served will also increase the propor-

tion of non-core intellectual antecedents synthesized in the content of their subse-

quent, post-acquisition inventions most highly.

Decomposing Patent Content

When patterns of patent citations were first related to the value of innovations (Griliches,

1981; Trajtenberg, 1990), scholars looked at their forward citations. Even when Trajtenberg, et

al. (1997) suggested the use of Herfindahl-like measures of patent citations, their discussion of

measurement was heavily-skewed towards an emphasis on the external validity provided by pa-

tents’ forward citations. In many subsequent studies, analysis of forward patent citation patterns,

i.e., the number and dispersion of citations garnered by patents after being granted, were used to

assess the influence of a firm’s most-important patents, and hence the value that they conveyed

(Ahuja & Lampert, 2001; Belazon, 2001; Cockburn & Griliches, 1988; Deng, Lev, & Narin,

1999; Hall, Jaffe, & Trajtenberg, 2005). Backward citations may be used as a proxy for the in-

puts to firms’ internal inventive activity. The backward-citation patent score indicates the extent

11

to which that patent synthesizes knowledge from across diverse scientific and technological

fields using a system of classification to track those technological class codes which contributed

to the invention.

There are many technology-coding classification systems that have been used to charac-

terize the technological content of a particular patent. Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) is

a bilateral coding system that was adopted (jointly with the European Patent Office) by the

USPTO on January 1, 2013. Like the International Patent Classification codes (IPC), CPC cod-

ing utilizes a system of letters and numbers—making it similar in spirit to the coding system of

the Derwent World Patents Index (which we chose). The Derwent World Patents Index (2013)

contains patent claims granted by the USPTO, but uses a classification system of 289 codes. We

chose their classification system for our calculations of patent scores because it was easily-

interpreted, parsimonious, and supported by a staff of classifying scientists and engineers who

were familiar with the equivalence of both coding systems (Zamojcin, 2013).1 Our patent-score

calculation methodology used a matrix that allowed for the comparison of as many as 289 tech-

nology class codes as a patent’s core knowledge; the operationalization of Trajtenberg, et al.

(1997)’s “originality” measure used a single code to represent the patent’s core knowledge (Hall,

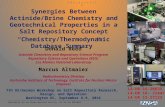

Trajtenberg, & Jaffe, 2001). Exhibit 1 lists several ways in which our backward-citation patent

scores differed from extant studies using patent data because of choices that we made.

----------------------------------------

Exhibit 1 and Figure 1 here

----------------------------------------

1 We did not use the recently-adopted Cooperative Patent Code (CPC) coding system because Thomson Reuters reported that they had not yet retroactively coded in CPC for all of the U.S. patents going backward in time as far as 1992 within the database that was available to us through Web of Science (2013).

12

Because we needed a measure that distinguished the highly-diverse technology classes

which were built upon from those technologies in the combined firm’s core, we built a concen-

tric measure which is depicted in Figure 1 (using two examples). In Figure 1, the firm’s core

knowledge is represented by the boldfaced, inner circle of technology class codes shown (which

represent the knowledge areas where a particular patent’s grant gives inventors temporary mo-

nopoly claims); the non-core knowledge that inventors built upon in order to earn each respec-

tive patent appears within the dashed-line circle outside of the patent’s respective knowledge

core (and those codes are not boldfaced).

Patent A in Figure 1 shows an example where an invention was patented in the core tech-

nology, S04 (clocks and timers). None of the knowledge that Patent A built upon (as evidenced

by the backward citations appearing in its patent application) came from S04. Instead, its inven-

tors built heavily on non-core knowledge of cryptography, computer peripherals, and broadcast-

ing receivers to create Patent A and because the knowledge incorporated in Patent A was widely

different, Patent A is scored highly. By contrast, Patent B in Figure 1 was granted for an inven-

tion in digital computers (T01) and audio-video recording systems (W04) where all of the back-

ward-cited patents appearing in its patent application were also previously granted claims in T01

and W04—as well as in five other, non-core knowledge areas. Although Patent B used some

knowledge that was non-core to the inventors, all of its intellectual precedents were patents that

had also been granted for applications of knowledge affecting digital computers and audio/ video

recording systems. Since Patent B’s backward-cited precedents were closer to its technological

expertise, Patent B has a lower score than Patent A. The creation of Patent B exploited applica-

tions of inventors’ extant knowledge while creation of Patent A required exploration of new

knowledge areas.

13

METHODOLOGY

Electronics firms were acquired by U.S. firms in our sample during the years of 1998

through 2005. Target firms that were acquired were identified by using their primary NAICS-

defined industry codes; acquiring firms could be from any NAICS-defined industries (but most

acquiring firms were also from the electronics industry). In addition to providing the criterion by

which observations entered our sample, NAICS-defined industry codes were also used to con-

struct a diversification score (to represent the breadth of each firm’s lines of business); infor-

mation from patent applications were used to calculate each firm’s annual patent scores (which

were the average of all individual patent scores that were calculated for that year).

Data and Sample

Thomson One’s Mergers & Acquisitions database (2013) reported that 2,921 acquisitions

of electronics firms had occurred during the eight-year window of 1998 to 2005—for which

COMPUSTAT financial data (2013) were available for 2,183 of the reported transactions. Be-

cause some firms made more than one electronics acquisition in a particular year that was in-

cluded within our window of observation, all transaction details per firm for each year were

combined to yield 1,236 usable observations covering eight possible years of acquisitions; 1,140

of those transactions involved firms who had patents i.e., the acquirer and/ or target firm in a par-

ticular transaction had patents in year0―which was how we coded the year when the transaction

closed―and change variables were calculated by comparing a four-year post-acquisition window

of financial (and patent-score) information with conditions that existed in year0.

Acquisitions selected for inclusion involved target firms that produced tangible electronic

products as well as related intangible IT services for them. The pre-set filters of the Thomson

One database generated a sample in which the primary NAICS-defined industries of the target

14

firms (TPRIMENAICS) included: semiconductors; electronic storage; communications equip-

ment; computing equipment; and software and IT technology services, among others. Although

the primary NAICS-defined industry code of the acquiring firms (APRIMENAICS) was allowed

to vary, only 36 acquiring firms were not primarily in electronics products. For 1,200 of the ob-

servations, the NAICS-defined primary industries of the acquiring firms included the same types

of electronics classifications: semiconductors, communications equipment, computer devices and

peripherals, active electronic components, and precision instruments, among others.

Constructing Patent Scores

In Figure 1, the patent examples each included a V-score which was our calculated esti-

mate of the breadth of diverse technological class codes represented by firms’ core knowledge

and the non-core knowledge that was utilized to create each invention. A high score represented

the synthesis of technological precedents from a broad range of technological classification

codes, while a low score reflected that a patent’s backward citations came from a narrower array

of technological classification codes.

V-score as corrected total patent score. Because our patent-score methodology allowed

for the inclusion of a large number of different core (and non-core) technology class codes for

each patent, the calculations were done in a spreadsheet matrix that juxtaposed each core tech-

nology class code with itself and all other technology class codes. Rows represented core- as

well as non-core codes; columns represented the core technology class codes awarded to a par-

ticular patent. The weightings by which counts of the frequency of each technology class code

were adjusted used averaged probabilities for each dyad of technology class codes occurring

15

(modified annually for each patent year).2 The backward-citation patent score, V, was equal to

the Raw Innovation Score (the sum of the core score and non-core score)―multiplied by a cor-

rection factor, [fo/fi], which was the ratio of the count of outside-the-core technology class

codes divided by the ratio of the count of inside-the-core technology class codes:

V = ([ai,ao ffk]k) [fo/fi]

The correction factor decomposed the sum of all technology class codes according to whether

they were inside-the-core or outside-the-core. The factor score was a useful criterion for sorting

patents by their mix of content.

Raw score as core and non-core scores. The Raw Innovation Score, Wk, was the sum of

all weighted scores for all technology class codes appearing in a particular patent, ([ai,ao

ffk]k), and it was also the sum of the core score and non-core score―which means that each

component of Wk could be investigated separately. Using the convention that in represented n-

different inside-the-core technology class codes that may appear in a patent and om represented

m- different outside-the-core technology class codes that may have been cited by that patent, we

calculated the average dyad weighting, ai or ao, for each respective technology class code as:

ai = pj/in for inside the core (and ao = pj/om for outside the core)

where pj was the dyad weighting for a particular core (or non-core) technology class code ap-

pearing with itself or with another backward-cited technology class code and j equaled n times (n

+ m). Each technology class code’s frequency factor, ffk, was calculated as:

ffk = fk/F

2 The probabilities per dyad occurring were based on the actual probability for the patent’s earliest priority date―which was the year of the first USPTO filing related to the patent that was ultimately granted.

16

where fk was the frequency with which a technology class code occurred in a particular patent

and F was the sum of all technology class codes appearing in that patent and k equals 1, 2, …, n,

n+1, …, n + m. The frequency factor was multiplied times the average dyad rating per technolo-

gy class code and summed according to whether the technology class code was inside-the-core or

outside-the-core in the patent award. The core and non-core scores were added together to create

the Raw Innovation Score. Non-core patent scores were used in some of the exhibits which fol-

low―in order to isolate the effects of the knowledge which was synthesized to create a particular

patent but which was coded differently from the codes contained in the patent’s award.

Weighting the frequency of technology class codes. The weightings by which the fre-

quency of core and non-core technology class codes were summed in our patent-score index

used the actual annual frequency with which specific dyads of technology class codes appeared

(relative to all of the other possible dyads that could have appeared together in a particular year).

The matrix of interaction dyads formed a Reference Table; the weightings in the Reference Table

were adjusted annually to reflect the nearness of technological confluence that was evolving as

knowledge was diffused.

Our weighting of the frequency of technology class codes differed from Hall, et al.

(2001)’s operationalization of Trajtenberg, et al.’s (1997) backward-citation patent score in three

important ways. First, Hall, et al. (2001) assigned weightings based on the frequency with which

codes occurred. Second, they did not distinguish the effects of core from non-core technology

class codes in calculating each patent’s score. Third, Hall, et al. (2001) did not adjust their

weightings to reflect the rate of technological change occurring―which accelerated over time

within many industries.

17

Aggregating a firm’s patent scores. All of a firm’s patent scores were averaged for each

year. Four-year average patent scores were calculated for the four-year periods occurring before

and after each year when an electronics acquisition occurred in order to detect post-acquisition

patent-score increases. The year in which acquisition transactions were consummated, year0, was

included in the four-year calculations of the pre-acquisition backward-citation patent

scores―which we coded as OLD scores to contrast with the post-acquisition patent scores,

which we coded as NEW. (We also calculated and analyzed seven-year old and new average pa-

tent scores for the pre- and post-acquisition period; significant differences between the results

obtained from the two sets of aggregated patent scores are reported—where they occurred.) Dif-

ferences between OLD and NEW patent scores are coded as NET (and the mean patent score

change between NEW and OLD was slightly negative, indicating substantial diversity in com-

bined firms’ inventive outputs).

Diversification Scores

We created a concentric index that indicated whether an acquiring firm was closely-

diversified (or not) by constructing measures that exploited the logic by which NAICS codes

were assigned. The North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS)―which was cre-

ated to account for North American trade flows―identifies similar technological products and

services by assigning them sequential or contiguous codes in its numbering schema (leaving

some sequential codes unused to allow for the invention of new, but currently-undiscovered,

technologies). The NAICS replaced the older Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code sys-

tem which Miller (2004) used for his concentric-index measure of technology breadth.

The SIC coding system was created before the development of many emerging and con-

verging electronic and/ or bioengineered technologies. (The NAICS classification system is an

18

improvement over the older SIC codes because highly-dissimilar technologies were sometimes

formerly classified under the same four-digit SIC code when using the older system while high-

ly-similar emerging technologies were sometimes given substantially-dissimilar SIC codes be-

cause the old system had not foreseen the development of such new industries.) Firms’ self-

reported six-digit NAICS codes were used to construct the diversification profile of each acquir-

ing and target firm in our sample, respectively.

Primary industry codes. In reporting the details of a particular acquisition, Thomson

One’s Mergers & Acquisition database (2013) supplied: the acquiring firm’s primary six-digit

NAICS-defined industry code (APRIMENAICS), the target firm’s primary six-digit NAICS-

defined industry code (TPRIMENAICS), and all other self-reported six-digit NAICS-defined

industry codes in which the acquiring firm and target were engaged during the year when their

particular transaction was consummated (which were coded as ANAICSx or TNAICSx, respec-

tively). Although the target firm’s primary industry code (TPRIMENAICS) was used to search

for acquisitions of electronics firms when constructing our sample, it was the primary industry

code of the acquiring firm (APRIMENAICS) that was used as the “central” point in calculating

and summing the distance scores (between each acquiring firm’s APRIMENAICS and each of

their respective ANAICSx codes) that were used to characterize its diversification posture. Our

calculation methodology was similar in spirit to the Euclidian distance measure used in cluster

analysis (Harrigan, 1985), and the sum of the distances between APRIMENAICS and each

ANAICSx code was normalized by dividing the sum by APRIMENAICS to create each acquiring

firm’s diversification score, AHH0:

AHH0 = (∑ |𝐴𝑃𝑅𝐼𝑀𝐸𝑁𝐴𝐼𝐶𝑆 − 𝐴𝑁𝐴𝐼𝐶𝑆𝑥|𝑛1 )/𝐴𝑃𝑅𝐼𝑀𝐸𝑁𝐴𝐼𝐶𝑆

19

where x = 1, 2, 3 …., n and the maximum value of n was 21 different ANAICSx industry codes.

For 32.6 percent of our sample, AHH0 equaled 0, which means that they were undiversified―as

defined by North American Industrial Classification System industry codes. The highest AHH0

score (9.249) was for Sony in 2004 (when 18 different ANAICSx industry codes were included

in that score); two years earlier, Sony’s AHH0 score was lower (4.874) because it was engaged in

only ten different ANAICSx industry codes in 2002.

The same methodology could be used to calculate diversification scores for each of the

target firms, THH0:

THH0 = (∑ |𝑇𝑃𝑅𝐼𝑀𝐸𝑁𝐴𝐼𝐶𝑆 − 𝑇𝑁𝐴𝐼𝐶𝑆𝑥|𝑛1 )/𝑇𝑃𝑅𝐼𝑀𝐸𝑁𝐴𝐼𝐶𝑆

where x = 1, 2, 3 …., n and the maximum value of n was the number of different NAICS-defined

industry codes that a target firm was engaged in.

Post-acquisition, combined-firm diversification scores. In our sample, if a particular

firm acquired more than one target firm in a particular year within the window of 1998 through

2005, the distances of all incremental TNAICSx industry codes (representing all acquired firms

of that particular year) were included when calculating the combined, post-acquisition diversifi-

cation score, CHH0:

CHH0 =𝐴𝐻𝐻0 + (∑ |𝐴𝑃𝑅𝐼𝑀𝐸𝑁𝐴𝐼𝐶𝑆 − 𝑇𝑁𝐴𝐼𝐶𝑆𝑥|𝑛1 )/𝐴𝑃𝑅𝐼𝑀𝐸𝑁𝐴𝐼𝐶𝑆

where x = 1, 2, 3 …., n and the maximum value of n was 27 different TNAICSx industry codes.

For 8.1 percent of our sample, CHH0 = 0, which means that they were undiversified―as defined

by North American Industrial Classification System industry codes―even after making their ac-

quisitions. The highest CHH0 score (9.78) was for Sony in 2004 (when the distances of two in-

cremental TNAICSx industry codes were added to Sony’s its AHH0 score to create that particu-

lar combined score). An acquisition which occurred in 2005 added the greatest number of com-

20

bined TNAICSx industry codes to the acquiring firm’s AHH0 score (and the acquiring firm was

L-3 Communications Holdings, Inc.); its AHH0 score was 0.0082 in 2005 before its acquisitions

were consummated (and its CHH0 score became 4.259 after the distances of 27 TNAICSx indus-

try codes of its acquired target firms were added to its AHH0 score).

Our CHH0 diversification scores should not be construed as representing an economic

characterization of the acquiring firms’ diversification (such as a weighted Herfindahl index).

Since we built our sample by searching for acquisitions of electronics firms using the TPRI-

MENAICS industry code from Thomson Reuters as our search criterion, it is plausible that the

acquiring firms may have made acquisitions of other, non-electronics target firms in each of our

eight window years which were not included in the calculation of our indices. The CHH0 diversi-

fication scores were created to be used as a basis for comparison when analyzing changes in ac-

quiring firms’ technological scores.

Pre-acquisition diversification scores for the acquiring firms (AHH0) were calcu-

lated for the year when their acquisition was consummated; where the acquiring firm bought

several target firms in the same year, all of the TNAICSx codes of all target firms acquired in that

particular year were used to calculate the incremental increases in the acquiring firm’s diversifi-

cation posture in order to create its post-acquisition, combined-firm diversification score

(CHH0). Where an acquiring firm had transactions in multiple, different years, unique post-

acquisition, combined-firm diversification scores (CHH0s) were calculated for each respective

year of transactions (because the target firms for each year of acquisitions were different).

Financial Performance Measures

Return on assets (ROA) ratios were calculated using financial information from COM-

PUSTAT (Standard & Poors,’ 2013). Financial performance improvements were calculated by

21

comparing return on total assets ratios that were calculated for year0 and year4 (or year7 in the

back-up analyses). A higher number of observations were available for year4 than for year7 due

to subsequent acquisitions of the acquiring firms themselves (or their removal from SEC filing

obligations). Patterns that juxtaposed patent scores with financial performance are reported using

non-parametric tests.

RESULTS

-----------------------------------

Exhibits 2a and 2b here

----------------------------------

Exhibits 2a and 2b describe the variables used in testing. Patent score distribution was

skewed downward from their mean values; only 41.2 percent of the sample had OLD patent

scores that were higher than the mean score of 34.33 and 38.3 percent of the sample had higher

NEW patent scores. Diversification scores were calculated from the NAICS-defined industry

codes to indicate whether an acquiring firm was relatively highly-diversified (or not), as well as

whether the addition of acquisitions of target firms made the acquiring firm’s diversification

score greater than it was (or not). Roughly 70 percent of our sample made additional acquisi-

tions within the decade following the transaction year that was under study in our sample.

Results Concerning Patent Scores

Exhibit 3―which compares OLD, acquiring firms’ 4-year average, backward-citation pa-

tent scores with ROA0, their returns on assets for year0―indicates that a significant proportion of

firms with higher patent scores (representing patents with greater proportions of non-core back-

ward citations) also enjoyed higher financial performance. The same patterns of significance

were also found for higher patent scores and returns on sales in year4 (and year7). Results suggest

that there is support for Hypothesis 1 which predicts that firms will reap financial benefits by

commercializing those inventions which stretch their technological knowledge beyond their core

22

knowledge by synthesizing broadly-diverse streams of technology. Micrel, Jabil Circuit, and

AVX Corp. were among this group of acquiring firms who had high four-year backward patent

scores and enjoyed high ROA performance.

-------------------

Exhibit 3 here

-------------------

Our patent scores were decomposed into core and non-core components for Exhibit 4

which juxtaposes the non-core portion of the backward-citation patent scores for year0 with the

non-core portion of the four-year scores in year4 to depict how the proportions of non-core con-

tent of the patent scores changed after acquisitions were made. Bracket points for the post-

acquisition scores were raised slightly in order to encompass an equivalent number of observa-

tions in each cell being analyzed. Results indicated a positive relationship between firms’ pre-

and post-acquisition backward-citation patent scores, suggesting that there is support for Hy-

pothesis 2a and evidence that absorptive capacity is persistent.

-------------------

Exhibit 4 here

-------------------

Moreover, Exhibit 4 indicates that the proportion of non-core knowledge being synthe-

sized in firms’ patents increased overall during the four years after their acquisition. The incre-

mental improvement in patent scores can be estimated by comparing the cell distributions out-

side the diagonals. Below the diagonal, the distribution of non-core, four-year patent scores has

increased for 23.49 percent of the sample from that score which existed in year0. Firms in this

group included AMKOR Technology, QLogic, and Semtech. Exhibit 4 also indicates that above

the diagonal, the distribution of non-core, four-year patent scores decreased by 19.81 percent.

Therefore Exhibit 4 suggests that a net increase for 3.68 percent of the sample is occurred—in

23

addition to the bracket change―to recognize that the overall proportion of non-core knowledge

included in patents has increased incrementally over the four post-acquisition years. (The net in-

crease was 4.83 percent when comparing patterns for the seven-year, non-core patent scores—

which suggests that more firms enjoyed post-acquisition innovation synergies as the window of

time examined was lengthened, but results were already palpable after four years of operating as

a combined firm.)

-------------------

Exhibit 5 here

-------------------

Exhibit 5―which compares the net changes in firms’ backward-citation patent scores

(for year4 minus year0) with changes in their return on assets (for the same comparison peri-

od)―reports that a significant proportion of those firms who achieved a net positive change in

the non-core content of their backward-citation patent scores (indicating multiplicative innova-

tion synergies) also enjoyed positive improvements in their return on assets. Firms accomplish-

ing the greatest improvement in their synthesis of non-core technologies included Broadwing

Corp, VeriFone Holdings, and DSP Group, among others. Results support Hypothesis 2b which

argues that firms showing increases in the diversity of technological antecedents being synthe-

sized in in their patents will enjoy improved financial performance after successfully integrating

their acquisitions.

When we investigated those cases where firms suffered post-acquisition deterioration in

their returns on assets, we found that 13.79 percent of those acquiring firms (who had patents in

year0) did not file any subsequent patent applications in the four years after consummating at

least one acquisition; by the seventh post-acquisition year, the proportion of firms filing no pa-

tent applications rises to 14.99 percent (and investigation thereof is the topic of another paper).

This patent-output pattern is disturbing because simple analysis of variance indicates that acquir-

24

ing firms having patents enjoyed return on asset ratios that were an average of 4 percent higher

than that of firms which had no patents in year0. Differences in their ROA performances were as

much as 12 percent higher for firms enjoying the highest post-acquisition returns in year4.

Results Concerning Diversification

Diversification was offered as a ‘straw man’ argument because it could have offered an

alternative explanation for changes seen in acquiring firms’ backward-citation patent scores. We

expected that the very act of adding business units which operated in more-diverse lines of busi-

ness would increase the proportion of non-core knowledge cited in firms’ patent applications.

Results from Exhibit 6 suggest that the opposite pattern existed in the electronics sample; our

line-of-business diversification score is negatively related to our backward-citation patent scores.

-------------------

Exhibit 6 here

-------------------

Exhibit 6 indicates that firms which diversified broadly from their historical core indus-

tries did not necessarily create inventions which reflected the broadest fusion of non-core techno-

logical knowledge. Contrary to expectations, when one controls for the core technology class

codes contained in each respective patent, highly-diversified firms did not bring in more non-

core technology class codes than narrowly diversified firms did in our sample. Briefly, it would

appear that a highly-diversified firm may be awarded patents in highly-diverse technological

fields, but the claims of those patents may rely on a very narrow array of non-core technologies

(if any); the highly-diversified firms appeared to be exploiting their extant core knowledge, not

stretching incrementally to master new knowledge areas. The innovation synergies which they

realized appear to be additive and hypothesis 3a has no support.

25

-------------------

Exhibit 7 here

-------------------

Exhibit 7 juxtaposes the NET changes in the non-core increment of firm’s four-year

backward citation scores with the target firm’s incremental contribution to the acquiring firm’s

diversification score. Results in Exhibit 7 are curvilinear and indicate that, contrary to what one

might expect, when a firm’s acquisitions diversified them greatly from their year0 diversification

posture, their backward-citation patent scores showed the lowest increase in incremental non-

core technologies. Conversely, those firms which diversified most narrowly (or not at all) in our

sample reflected the greatest incremental use of novel, non-core areas of technology in their in-

ventions. Results from Exhibits 6 and 7 indicate that there was no support for Hypotheses 3a and

3b which had suggested that a posture of broad diversification would have a positive relationship

with the breadth of non-core technological fields that subsequent patents would build upon.

-------------------

Exhibit 8 here

-------------------

Exhibit 8 tests models of the effects of backward-citation patent scores and diversifica-

tion on return on assets for the third, fourth, and fifth years after acquisition. In all specifications,

the patent score variable is lagged by two years; its sign is positive and significant. The patent

productivity variable is also positive and significant. (It was constructed by dividing the number

of patents awarded by R&D expenses.) The diversification variable is always negative and sig-

nificant. The R&D divided by sales variable (which was tested in model 6) is negative and high-

ly significant. Its inclusion in model specifications made the backward-citation patent scores

weakly significant. The logarithm of sales control variable is always positive and highly signifi-

cant (indicating that larger firms enjoyed the positive benefits of scale economies). The leverage

and assets per employee productivity ratios were weakly significant (or not significant at all).

26

Results are consistent with Hypothesis 1 and indicate that firms having higher backward-citation

patent scores enjoyed higher returns on assets. The negative signs of the diversification variable

suggest that there is no evidence to accept Hypotheses 3a and 3b because diversification and

backward patent scores are negatively correlated.

Discussion of Results

Results have shown evidence that firms whose patents incorporated knowledge from a

wide variety of non-core technological fields enjoyed superior returns on investment. We found

that higher returns on assets were realized within combined firms where effective cross-

fertilization and knowledge sharing fostered the type of organizational learning that allowed

those firms’ inventors to stretch the range of non-core technological fields being synthesized in

their patents. Higher financial performance appears to be associated with such patterns of broad-

ly-diverse backward patent citations and this result does not seem to be due to diversification.

Higher post-acquisition patent scores were not found with broad diversification. We concluded

that the incremental increases in patent scores were due to organizational learning which would

not be otherwise possible―which we argue is evidence of multiplicative, post-acquisition inno-

vation synergies.

Because multiplicative innovation synergies are stimulated by working with capabilities

beyond those mastered internally, firms make acquisitions (or form alliances) to learn about di-

verse knowledge and gain needed capabilities, knowledge and expertise (Harrigan, 1988; Hitt, et

al., 1991; Kogut, 1988; 1991; Sears and Hoetker, 2014; Winter, 2003). Successful post-

acquisition organizational learning, cross-fertilization, and knowledge-sharing activities are not

guaranteed. Hitt, Hoskisson, & Ireland, (1990) suggested that the pattern of the firm’s technolog-

ical antecedents would spike immediately after an acquisition—flattening over time if the ac-

27

quirer did not combine the technology of the target firm with its own. But if the post-integration

learning activity were instead synergistic, the greater complementarity enjoyed would reflected

in improved backward-citation scores (Argyres and Silverman, 2004; Belenzon, 2001; Miller, et

al, 2014). Effectively-integrated organizations can amplify their knowledge of unknown technol-

ogies more constructively than the individual parties could do were they not so combined.

Limitations of Results

Our sample was drawn from the acquisitions of electronics targets within an industry that

was deeply affected by rapid obsolescence associated with the commercialization of Internet-

based technologies. Results in our tests may not reflect relationships in other technology-

intensive industries that experienced differing rates of technological obsolescence, e.g., pharma-

ceuticals.

Our financial data were limited to those available from firms making SEC filings. We do

not know whether private firms having no patents outperformed the electronics firms within our

sample because we lack such data.

We found that patent scores indicating high proportions of non-core precedents were as-

sociated with higher financial returns. Differing results may have been obtained if an alternative

technology classification system had been used to identify a patent’s core and non-core technol-

ogy class codes, e.g., using the USPTO classification system, International Patent Classification

system (IPC), or Cooperative Patent Classification system (CPC)—or the sub-classifications

used within each respective classification system—may have provided finer-grained distinctions

among the technological areas within patented inventions that would negate our findings of

higher financial performance. In particular, our results should be compared with the backward-

citation patent scores obtained using Hall, et al. (2001)’s truncated system of technology classifi-

28

cation to ascertain whether there are indeed significant distinctions obtained from including more

technology class codes when characterizing firms’ technological cores. Different relationships

may also have been found if the numerous manual sub-codes of the Derwent World Patent Index

classification system (2013)—which provide a finer-grained distinction between technological

classes—had been used instead for categorizing patents’ content.

Finally greater analysis of the relationship between our line-of-business diversification

scores and backward-citation scores is needed. Although Rumelt (1982) and Amit & Livnat

(1988) found that related diversifiers do not outperform single-business firms financially, we

found no relationship between our diversification score and financial performance.

Implications of Results and Conclusions

In this study, we examined firms’ patents using backward-citation patterns to find evi-

dence of post-acquisition multiplicative integration synergies. We assumed that the effective

post-acquisition integration of inventive organizations would result in the creation of inventions

that reflected the synthesis of knowledge outside of the firm’s historical comfort zone. We ex-

pected that multiplicative innovation synergies would ultimately yield improved financial per-

formance. Our results suggest that higher returns are earned when firms’ patents reflect radical

patterns in their technology synthesis. Results are persistent over time for firms who continue to

push their learning envelope by using non-core technologies significantly in their inventions.

The next big conglomerate wave may soon be upon us as acquisition sprees by technolo-

gy firms like Google and Cisco transform these pioneers into technology conglomerates. Our re-

sults suggest that successful attainment of multiplicative innovation synergies will be an im-

portant means of earning the required performance improvements (RPIs) that will be needed to

amortize the acquisition premiums that they have paid. It will be important for such firms to

29

combine the inventive resources of the firms that they have acquired through carefully-

implemented integration processes in order to preserve all opportunities for the organizational

learning that comes when researchers stretch beyond their comfortable knowledge cores to syn-

thesize inventions from remote technological arenas, as our findings have suggested.

30

References

Afuah, A.N., & Bahram, N. 1995. The hypercube of innovation. Research Policy, 24: 51–76.

Ahuja, G., & Katila, R. 2001. Technological acquisitions and the innovation performance of ac-

quiring firms: a longitudinal study. Strategic Management Journal, 99(3): 197-220.

Ahuja, G., & Lampert, C.M. 2001. Entrepreneurship in large corporations: A longitudinal study

of how established firms create breakthrough inventions. Strategic Management Jour-

nal, 22: 521–543.

Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M.W. 2009. Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational

ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organization Science, 20: 696–717.

Argyres, N.S., & Silverman, B. 2004. R&D, organization structure, and the development of cor-

porate technological knowledge. Strategic Management Journal, 25: 929–958.

Belenzon, S. 2011. Cumulative innovation and market value: Evidence from patent citations.

Economic Journal, 122:265–285.

Cassiman, B., Colombo, M.G., Garrone, P., & Veugelers, R. 2005. The impact of M&A on the

R&D process―An empirical analysis of the role of technological- and market-

relatedness. Research Policy, 34(2): 195-220.

Catozzella, A., & Vivarelli, M. 2014. Beyond absorptive capacity: in-house R&D as a driver of

innovative complementarities, Applied Economics Letters, 21:1, 39-42

Cloodt, M., Hagedoorn, J., & Van Kranenburg, H. 2006. Mergers and Acquisitions: their effect

on the innovative performance of companies in high-tech industries. Research Policy, 35:

642-668.

Cockburn, I.M, & Griliches, Z. 1988. Industry effects and appropriability measures in the stock

market’s valuation of R&D and patents. American Economic Review, Papers and Pro-

ceedings, 78: 419–423.

Cockburn, I.M., & Henderson R.M. 1998. Absorptive capacity, coauthoring behavior, and the

organization of research in drug discovery. Journal of Industrial Economics. 46(2): 157-

182.

Cohen, W.M., & Levinthal, D.A. 1990. Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and

invention. Administrative Science Quarterly. 35: 128-152.

Collins, J., & Porras, J.I. 1994. Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies.

HarperBusiness: New York.

31

Dahlin, K.B., & Behrens, D.M. 2005. When is an invention really radical? Defining and measur-

ing technological radicalness. Research Policy, 34: 717–737.

Deng, Z., Lev, B., & Narin, F. 1999. Science and technology as predictors of stock performance.

Financial Analysts Journal, 553: 20–32.

Department of Commerce. 2013. United States Patent and Trademark Office.

Derwent Innovation Index. 2013. Web of Science. Thomson Reuters: NY.

Eccles, R.G., Lanes, K.L., & Wilson, T.C. 1999. Are you paying too much for that acquisition?”

Harvard Business Review. 79(4): 136-146.

Fleming, L. 2001. Recombinant uncertainty in technological search. Management Science, 47:

117-132.

Fulghieri, P., & Hodrick, L.S. 2006. Synergies and internal agency conflicts: the double-edged

sword of mergers, Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 15(3): 549-576.

Graebner, M. 2004. Momentum and serendipity: how acquired leaders create value in the inte-

gration of technology firms. Strategic Management Journal, 25: 751-777.

Griliches, Z. 1981. Market value, R&D and patents. Economic Letters, 7: 183-187.

Grimpe, C., & Hussinger, K. 2014. Resource complementarity and value capture in firm acquisi-

tions: the role of intellectual property rights. Strategic Management Journal, 35: 1762-

1780.

Guralnik, D.B., ed., 1970. Webster’s New World Dictionary of the American Language.

(Second College Edition) The World Publishing Company: New York.

Hagedoorn, J., & Cloodt, M. 2003. Measuring innovative performance: is there an advantage in

using multiple indicators. Research Policy, 32: 1365-1379.

Hagedoorn, J., & Duysters, G. 2002. The effect of mergers and acquisitions on the technological

performance of companies in a high-tech environment. Technology Analysis & Strategic

Management, 14: 67-89.

Hall, B.H., Jaffe, A.B., & Trajtenberg, M. 2001. The NBER patent citations data file: Lessons,

insights and methodological tools. NBER working paper no. 8498.

Hall, B.H., Jaffe, A.B., & Trajtenberg, M. 2005. Market value and patent citations. RAND Jour-

nal of Economics, 36: 16–38.

Harrigan, K.R. 1985. An application of clustering for strategic groups analysis. Strategic Man-

agement Journal, 6(1): 55-73.

32

Harrigan, K.R. 1988. Joint ventures and competitive strategy. Strategic Management Journal.

9: 141–158.

Henderson, R. 1993. Underinvestment and incompetence as responses to radical innovation: evi-

dence from the photolithographic alignment equipment industry. Rand Journal of Eco-

nomics. 24:248–270.

Hitt, M.A., Hoskisson, R.E., & Ireland, R.D. 1990. Mergers and acquisitions and managerial

commitment to innovation in M-form firms. Strategic Management Journal. 11: 20–47.

Hitt, M.A., Hoskisson, RE., Ireland, R.D., & Harrison, J.S. 1991. Effects of acquisitions on R&D

inputs and outputs. Academy of Management Journal. 34: 693–706.

Hussinger, K. 2012. Absorptive capacity and post-acquisition inventor productivity. Journal of

Technology Transfer. 37:490-507.

Kim, C., Song, J.Y., & Nerkar, A. 2012. Learning and innovation: Exploitation and exploration

trade-offs. Journal of Business Research. 65: 1189–1194.

Kogut, B. 1988. Joint ventures―theoretical and empirical-perspectives. Strategic Management

Journal. 9(4): 319-332.

Kogut, B. 1991. Joint ventures and the option to expand and acquire. Management Science.

37(1): 19-33.

Kogut, B. & Zander, U. 1992. Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities and the replica-

tion of technology. Organization Science. 3: 383–397.

Lavie, D., & Rosenkopf, L. 2006. Balancing exploration and exploitation in alliance formation.

Academy of Management Journal. 49: 797–818.

Lettl, C., Herstatt, C., & Gemuenden, H.G. 2006. Learning from users for radical innovation. In-

ternational Journal of Technology Management. 33: 25–45.

Lichtenthaler, U. 2009. Absorptive capacity, environmental turbulence, and the complementarity

of organizational learning processes. Academy of Management Journal. 52(4): 822-846.

Makri, M., Hitt, M.A. Lane, P.J. 2010. Complementary technologies, knowledge relatedness, and

invention outcomes in high technology mergers and acquisitions. Strategic Management

Journal. 31(6): 602-628.

March, J.G. 1991. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Sci-

ence. 2:71–87.

33

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. 1997. Event studies in management research: theoretical and em-

pirical issues. Academy of Management Journal. 40(3): 626-657.

Miller, D.J. 2004. Firms’ technological resources and the performance effects of diversification:

a longitudinal study. Strategic Management Journal, 25: 1097-1119.

Miller, D.J. 2006. Technological diversity, related diversification, and firm performance. Strate-

gic Management Journal, 27: 601-619.

Miller, D.J., Seth, A., & Lan S. 2014. Innovation synergy in acquisitions: an evaluation of patent

and product portfolios. Working paper. University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana.

Narasimhan, O., Rajiv, S., & Dutta, S. 2006. Absorptive capacity in high-technology markets:

the competitive advantage of the haves. Marketing Science. 25(5): 510-524

Paruchuri, S., Nerkar, A., & Hambrick, D.C. 2006. Acquisition integration and productivity loss-

es in the technical core: Disruption of inventors in acquired companies. Organization

Science. 17(5): 545-562.

Rosenkopf, L., & Nerkar, A. 2001. Beyond local search: Boundary-spanning, exploration, and

impact in the optical disk industry. Strategic Management Journal. 22: 287–306.

Schoenmakers,W., & Duysters, G. 2010. The technological origins of radical inventions. Re-

search Policy. 39: 1051–1059.

Schumpeter, JA. 1951. The creative response in economic history. Journal of Economic Histo-

ry. 7: 149–159.

Sears, J.B., & Hoetker, G. 2014. Technological overlap, technological capabilities, and resource

recombination in technological acquisitions. Strategic Management Journal. 35: 48–67.

Sirower, M.L. 1997. The synergy trap: How companies lose the acquisition game. Free Press:

NY.

Sorensen, J.B., & Stuart, T.E. 2000. Aging, obsolescence and organizational innovation. Admin-

istrative Science Quarterly, 45: 81-112.

Standard & Poor’s 2013. COMPUSTAT Database. McGraw-Hill: NY.

Thomson Reuters. 2013. Thomson One Mergers & Acquisitions. SDC Platinum Database.

Trajtenberg, M. 1990. A penny for your quotes: patent citations and the value of innovations.

RAND Journal of Economics, 21: 172–187.

34

Trajtenberg, M., Henderson, R., & Jaffe, A. 1997. University versus corporate patents: A win-

dow on the basicness of invention. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 5:

19–50.

Tripsas, M., & Gavetti, G. 2000. Capabilities, cognition, and inertia: Evidence from digital imag-

ing. Strategic Management Journal. 21: 1147–1161.

Winter, S.G. 2003. Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24:

991–995.

Zamojcin, T. 2013. Personal communication and interview notes. Thomson Reuters: NY. 6 Au-

gust 2014.

35

W03

P85 = Cryptography

S04 = Clocks and Timers

T01 = Digital Computers

T03 = Data Recording

T04 = Computer Peripherals

T06 = Process Controls

U21 = Logic Circuits

W02 = Broadcasting, Line Transmission

W03 = TV, Broadcast Radio Receivers

W04 = Audio/ Video Recording Systems

Figure 1

Radicalness of Patent Antecedents: A Comparison

T04 T03, T06

W02, W03

T01,

W04

P85

S04

Backward-cited patents for US6238084-B1 contained no in-

tellectual precedents having S04 knowledge (boldfaced)

among their granted claims. Creation of patent US6238084-

B1required synthesis of several other technology class codes

which were not among its inventors’ core knowledge

Patent A:

US6238084-B1

Patent B:

US6026232-A

All backward-cited patents for US6026232-A contained T01

and W04 (boldfaced) among their respective granted

claims. Some of the backward-cited precedents were grant-

ed claims in other technology class codes which were not

among the claims granted to patent US6026232-A

V-Score = 84.0.429 V-Score = 19.3282

Key: Boldfaced technology class codes represent codes of claims awarded to patent in its grant

- - - Codes inside circle drawn using dashed-lines represent technology class codes of backward-cited patents (intel-

lectual precedents) which may have been added by Patent Examiner (or claimant firm’s lawyers) to indicate range of

technological areas which were synthesized in order to create invention for which patent has been granted

Coding is from Derwent World Patents Index

36

Exhibit 1

Adjustments Made to Calculate Patent Scores Using Backward Citations

Choice Made

Each patent is shown to have multiple

technological class codes in its grant

―representing its core knowledge

(shown as boldfaced codes in Figure 1)

The 289 technology class codes of Der-

went World Patents Indexing system

were used to characterize each patent’s

core and non-core areas of knowledge

Alternative Way to Design Scores

One technology class code per patent

could be used to represent core

knowledge (as was done in Hall, Tra-

jtenberg & Jaffe, 2001 and many studies

thereafter which used their methodology)

Hall, et al. (2001)'s 96-code classifica-

tion system (based on a condensation of

USPTO classification codes representing

over 120,000 technological classes) used

one code per core area of knowledge

Rationale for Choice

Desire to capture a more accurate and

broad characterization of range of firm's

core knowledge by using all of the tech-

nological class code information that was

associated with each respective patent's

grant

Derwent coding system is a compromise

between Hall, et al (2001)’s parsimoni-

ous classification system representing

289 technological class codes (and full

range of USPTO codes) supported by

Thomson Reuters

37

Choice Made

Patent scores were calculated based on

“earliest priority date,”―the year when

the firm first filed papers regarding its

idea with USPTO (which was sometimes

earlier than the year when a formal pa-

tent application was filed)

Joint occurrence of each patent’s inside-

the-core and outside-the-core technology

class code dyads are used to provide

weightings that represent "distances" be-

tween patent’s core knowledge and its

backward-cited knowledge precedents

(to capture extent of technological diver-

sification represented by each patent

Alternative Way to Design Scores

Patent scores could be calculated using

the application year as basis for compari-

son of technological dyads that frequent-

ly appear together

Some other weighting scheme could

have been used when aggregating a

year’s set of granted patents

Rationale for Choice

Desire to capture those comparative

technological "distances" in weighting

scheme that were in effect when inven-

tion was first conceived (to reflect state

of technological progress at that time)

Desire to approximate the similarity of

seemingly different technology class

codes appearing as precedents in patent

examiner's report of originality

38

Choice Made

Weightings representing "distances" be-

tween core and non-core technology

class codes are adjusted annually to re-

flect technological convergences occur-

ring over time

Alternative Way to Design Scores

No adjustment could have been made for

the year by year convergences in joint

use of technological class codes that was

occurring

Rationale for Choice

Technological confluence accelerated

over time―making certain technology

class code dyads appear together more

frequently, thereby reducing their "dis-

tance" from each other as time passed

39

Exhibit 2a

Variable Descriptions

Variable

Name Explanation Mean Std. Dev. Minimum Maximum

AHH0 Acquirer's diversification score 0.519 0.833 0.000 9.249

CHH0 Combined firm's diversification score 1.084 1.405 0.000 9.780

ROA0 Return on assets in year of acquisition 0.030 0.390 -1.840 0.428

ROA3 Return on assets three years after acquisition 0.018 0.327 -1.672 0.506

ROA4 Return on assets four years after acquisition 0.026 0.288 -5.062 0.391

ROA5 Return on assets five years after acquisition 0.339 0.324 -5.672 0.362

OLD Average patent scores for four years prior to acquisition 34.331 14.353 0.000 156.714

NEW Average patent scores for four years after acquisition 36.396 17.824 0.000 233.150

NET Difference in average patent scores (NEW minus OLD) 0.687 24.121 -129.528 188.260

BACK1 Backward patent score one year after acquisition 35.489 17.913 0.050 240.602

BACK2 Backward patent score two years after acquisition 37.259 19.075 0.050 197.422

BACK3 Backward patent score three years after acquisition 39.257 21.880 0.050 255.405

40

RD4 R&D expense divided by sales in fourth year 0.324 2.121 0.000 39.074

PCOST2 Patents divided by R&D expense in second year 0.718 1.350 0.000 14.737

PCOST3 Patents divided by R&D expense in third year 0.658 1.304 0.000 14.737

PCOST4 Patents divided by R&D expense in fourth year 0.602 1.111 0.002 14.603

PRODTV3 Sales divided by employees in third year 0.276 0.186 0.000 1.803

PRODTV4 Sales divided by employees in fourth year 0.285 0.191 0.002 1.921

PRODTV5 Sales divided by employees in fifth year 0.300 0.209 0.001 2.141

LOGSALES3 Logarithm of sales in third year after acquisition 2.645 1.012 -0.724 5.073

LOGSALES4 Logarithm of sales in third year after acquisition 2.695 1.001 -0.724 5.073

LOGSALES5 Logarithm of sales in third year after acquisition 2.747 1.005 -1.194 5.100

LEVERG3 Long-term debt divided by total assets in third year 0.118 0.159 0.000 0.968

LEVERG4 Long-term debt divided by total assets in fourth year 0.117 0.160 0.000 0.918

41

Exhibit 2b

Pearson Correlation Coefficients

Prob > |r| under H0: Rho=0

AHH0 CHH0 ROA0 ROA3 ROA4 ROA5 OLD NEW NET BACK1 BACK2

CHH0 0.7799

<.0001

ROA0 0.0343 0.0460

0.2370 0.1124

ROA3 0.0306 0.0433 0.4693

0.3481 0.1844 <.0001

ROA4 -0.0107 0.0311 0.5135 0.7060

0.7514 0.3552 <.0001 <.0001

ROA5 -0.0524 -0.0061 0.5139 0.5833 0.7521

0.1284 0.8594 <.0001 <.0001 <.0001

OLD -0.0066 -0.0514 0.0316 0.0920 0.0962 0.1021

0.8294 0.0915 0.3080 0.0073 0.0062 0.0044

NEW -0.0387 -0.0449 -0.0211 0.0310 -0.0255 0.0161 0.2427

0.2154 0.1508 0.5057 0.3689 0.4710 0.6557 <.0001

NET 0.0121 0.0217 0.0720 -0.0173 -0.0026 0.0108 -0.4831 0.7120

0.6844 0.4638 0.0169 0.6059 0.9394 0.7578 <.0001 <.0001

BACK1 -0.0480 -0.0482 -0.0492 0.0296 -0.0537 -0.0228 0.1674 0.5465 0.3332

0.1655 0.1635 0.1592 0.4346 0.1624 0.5606 <.0001 <.0001 <.0001

42

AHH0 CHH0 ROA0 ROA3 ROA4 ROA5 OLD NEW NET BACK1 BACK2

BACK2 -0.0510 -0.0369 -0.0436 -0.0166 -0.0590 -0.0227 0.1521 0.6317 0.3980 0.2654

0.1541 0.3023 0.2271 0.6677 0.1310 0.5680 <.0001 <.0001 <.0001 <.0001

BACK3 -0.0841 -0.0570 -0.0574 0.0174 0.0107 0.0200 0.1462 0.6320 0.4236 0.1996 0.3353

0.0217 0.1204 0.1210 0.6550 0.7862 0.6175 <.0001 <.0001 <.0001 <.0001 <.0001

RD4 0.0670 0.0222 -0.3729 -0.3517 -0.3871 -0.5575 -0.0321 0.0449 -0.0390 -0.0263 0.1421

0.0524 0.5201 <.0001 <.0001 <.0001 <.0001 0.3727 0.2121 0.2691 0.4989 0.0003

PCOST2 -0.0885 -0.1218 0.0455 0.0913 0.0715 0.0823 0.0355 -0.0138 -0.0323 -0.0336 -0.0128

0.0165 0.0010 0.2225 0.0187 0.0696 0.0400 0.3418 0.7098 0.3835 0.3810 0.7318

PCOST3 -0.0805 -0.1021 0.0389 0.1074 0.1010 0.1133 -0.0146 -0.0024 0.0163 -0.0272 0.0209