European Lobbying

-

Upload

zeina-roumi -

Category

Documents

-

view

226 -

download

0

Transcript of European Lobbying

8/8/2019 European Lobbying

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/european-lobbying 2/12

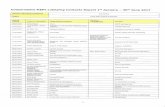

Index

Introduction

1. Casis de Dijon……………………………………………………………………………………………

2. Stakeholders………………………………………………………………………………………………

3. Objectives………………………………………………………………………………………………….

4. Communication Statement………………………………………………………………………..

5. Consequences…………………………………………………………………………………………….

Conclusion

2

8/8/2019 European Lobbying

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/european-lobbying 3/12

Introduction

In this paper we will talk about the “Cassis de Dijon”. Cassis de Dijon is a French

liqueur manufactured from black currants. Cassis contains 15%-20% alcohol and

the German standards prescribed 25%. For the Germans the percentage of

alcohol became a problem as it wasn’t their standards.

3

8/8/2019 European Lobbying

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/european-lobbying 4/12

Cassis de Dijon

In the "Cassis de Dijon" case, the European Court of Justice struck down aGerman import prohibition. The prohibition disallowed the import, sale and/or

marketing of liqueurs in Germany that didn't meet minimum German alcoholstandards of 25 %. The ruling gave the European Commission an opportunity todevelop the principle of "mutual recognition."

In February 1979, the European Court of Justice struck down a Germanprohibition on imports from other European Union (EU) countries. The prohibitionbanned the importation of alcoholic beverages that did not meet minimumalcohol content requirements. The case involved Cassis de Dijon, a French liqueurmanufactured from black currants. Cassis contains 15%-20% alcohol and theGerman standards prescribed 25%. Rowe-Zentral AG, a German import/exportfirm, brought suit charging that the German regulation on minimum alcoholcontents was an illegal non-tariff barrier.

The German government argued the validity of its regulation primarily on healthgrounds, claiming that the law existed to avoid the proliferation of alcoholicbeverages within the German market. It argued that beverages with lowalcoholic content induce a tolerance toward alcoholism more so than highlyalcoholic beverages. Germany also offered a consumer protection justificationclaiming there was a need to protect consumers from unfair producer anddistributor practices. In its final argument, the German government argued thatthe elimination of the import ban would mean that one country could set thestandards for all member states, thus precipitating a lowering of standardsthroughout the EU.

After the case was brought against the German courts, the European Court of Justice ruled that because Cassis met French standards, it could not be kept outof the German market.

The European Court rejected the German health argument as unconvincing anddismissed the its consumer protection justification. After rejecting the Germandefense claims, theCourt spelled out the general principle, which is now the most famous part of theruling: "There is therefore no valid reason why, provided that they have beenlawfully produced and marketed in one of the Member States, alcoholicbeverages should not beintroduced into any other Member State."

The Court ruled that barriers to trade were allowed only to satisfy mandatoryrequirements relating to the effectiveness of fiscal supervision, the protection of public health, the fairness of commercial transactions and the defense of theconsumer. When these conditions are threatened and import prohibitions arefound to be valid, the EU's Commission would provide minimum standards in theform of a directive. Member states would then be obliged to harmonize theirstandards to meet the criteria set out in Commission directives.

Cassis gained notoriety when a political debate was instigated by theCommission. The Commission extracted the aspects of the ruling that were

useful for eliminating nontariff

4

8/8/2019 European Lobbying

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/european-lobbying 5/12

trade barriers. In the Fall of 1979 Etienne Davignon, the internal marketcommissioner, suggested in front of the EU Parliament that trade policy shouldtake a new direction based on the Cassis ruling.

The Official Journal of the European Communities states, "Any product importedfrom another member state must in principle be admitted...if it has been lawfullyproduced, that is, conforms to rules and processes of manufacture that arecustomarily and traditionally accepted in the exporting country."

Stakeholders

Stakeholders

• Company producing the Cassis de Dijon – They were of course affected,but since they won the case in the end everything worked out for them.

They were able to sell their liquor in other countries after the court decidedon the case.

• The company in Germany who was going to sell the liquor – They were thesecond of the major parties involved in this case and of course they wereaffected by it. Now the liquor actually could be sold in their store and in thesame classification as other liquors, even though the percentage waslower. The German law no longer restricted them for selling the Cassis deDijon there.

• Countries involved – Germany and France were the countries involved,since France was the country producing the liquor and Germany thecountry that they wanted to export it to. After the case the regulations inthe countries changed.

• Consumers of the liquor – The consumers here refers primarily to theconsumers in Germany. Since the consumers in France already couldconsume it without any restrictions this did not affect them. But the onesin Germany were because of the precious restriction and after the case

now could consume it.

• Others affected by the principle – Since this case actually evolved into aprinciple a lot of more people were affected. The principle says thatanything that is produced in one member state can be sold legally to othermember states as well. So other companies that have been restrictedbefore can now sell their product in other countries.

• People in Germany who were defending the standard – When defending

the case to why it should not be classified as liquor, Germany said that itwas for health-reasons. That if it is called liquor with that low percentage

5

8/8/2019 European Lobbying

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/european-lobbying 6/12

for alcohol, people will be consuming more of it since it is so low. And inGermany there were probably people defending this and seeing it as aproblem. For them this new legislation is against what they believe in.

6

8/8/2019 European Lobbying

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/european-lobbying 9/12

Consequences

There are ways in which the European court of justice often creates exceptions toits broad general principles, so the Cassis de Dijon case has caused manyproblems to the European court of justice because now member states seek to

justify their restrictions, while the traders attempt to attack any national lawswhich restrict trade practices or commercial freedom. But on the other hand, thiscase assists to clarify the principle of the free movement of goods under Articles28 (formerly 30) and 29 (formerly 34) and its exception under Article 30 (formerly36) of the Treaty on European Union.

There are two principles of laws arising from this case.

1. Principle of Equivalence. The European court justice stated that:

“ There is ...no valid reason why, provided that they have been lawfully produced

and marketed in one of the Member States, alcoholic beverages should not beintroduced into any other Member State; the sale of such products may besubject to a legal prohibition on the marketing of beverages with an alcoholiccontent lower than the limit set by national rules.”

This principle provides that if a product meets the standards of member state of export, that product should be regarded also as meeting the standards of themember state of import. This principle is also confirmed in the case of Italy v.Nespoli and on some other cases. The European court justice in this case heldthat as a general rule, if the imports are lawfully manufactured and marketed inone member state, they are entitled to enter another member state withoutobstacles, restrictions and measures having an equivalent effect.

This Examines how the European Union rules on the free movement of goods,showing that the European Court of Justice has established an approach todisputes balancing the interests of producers and consumers while givingmanufacturers and traders a fair hearing.

2. The second is the Principle of the Rule of Reason:

The European court justice in Cassis de Dijon held that in case of no communitylegislation, the exceptions of the free movement of goods principle coming fromthe disapproval of the national legislations must be accepted if those exceptions

are necessary to satisfy the mandatory requirements relating in particular to theeffectiveness of fiscal supervision; the protection of public health; the fairness of commercial transactions; and the defense of the consumer.

Also this is confirmed in another case. In German Sausages case, Commission v.Germany; the facts were German law prohibited the sale of sausages containingadditives in Germany. This law applied to both German products and productsfrom other European Union member states, even though, the additives were notprohibited by the law of origin in member state. The European court justice heldthat the ban was an unlawful restriction under Article 28 (formerly 30) and couldnot justified under the rule of reason because consumers could be adequately

protected by means of proper labelling of products.

9

8/8/2019 European Lobbying

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/european-lobbying 10/12

The European court justice has narrowly interpreted these exceptions by sayingthat the restriction of trade must not be discriminatory in goods originating in onemember state from those of the others. Also, it must not be discriminatory indomestic goods from the goods imported from the member states.

COMMENTS

It is explicit that although the objective and the provisions of the European Union Treaty confirm the free movement of goods notion, the freedom to move goodsacross border without any restrictions has still been obstructed.

This is because of two obstacles.

1. The first is the interpretation of the European court justice on the generalprovisions of the free movement of goods.

2. Second is the exception provisions contained in Article 30 (formerly 36) of the Treaty itself and the exceptions based on mandatory requirements

arising from the European court justice in Cassis de Dijon.

These two obstacles make it difficult to have freedom to move goods acrossborders. The European court justice and all European Union member states are inthe position to break down these obstacles.

Also the European court justice must interpret the general provisions of the freemovement of goods as widely as possible. For example the European court

justice when defining "goods" it should cover both tangible products andintangible products, like energy. And also apply the free movement of goodsprovisions to all types of movements: traders, individuals, commercial

transactions and non-commercial transactions.

For the meaning of "similar" products, the European court justice should interpretit to cover "substituted products"; for example fish sauce and salt. Furthermore,the European court justice should clarify the meaning of "selling arrangements"and draw the vivid distinction between measures relating to selling arrangementsand measures relating to the goods.

The degrees of public morality, public policy, public security, health and life of humans, animals or plants protection and industrial and commercial propertyprotection may vary from one member state to another because they are foreach member state to determine in accordance with its own scale of values andthe requirements of protection. However, the European court justice can limit thescope of their effects by applying the principle of non discrimination and theprinciple of proportionality.

The European court justice must narrowly the scope of the meaning of mandatoryrequirements, the exceptions arising from Cassis de Dijon because mandatoryrequirements create a decrease from the fundamental principle of the freemovement of goods. Therefore, it must be interpreted strictly, not to extend itseffects further than is necessary for the protection of the public interests.Moreover, it is generally accepted that it is very hard to tell all of which constitutethe mandatory requirements. For example, it is still controversial whether the

protection of culture constitutes the mandatory requirements because the cultureof one member state may be totally different or even opposite from that of the

10

8/8/2019 European Lobbying

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/european-lobbying 11/12

others. However, the European court justice can limit its scope by applying theprinciple of non discrimination and the principle of proportionality to suchrestrictions.

In the cases of justification, the European court justice must specify and clarify inevery judgment the ground and reason of the justification whether it is underArticle 30 (formerly 36) or the mandatory requirements. The proof to justify therestrictions must be rested with member state who seeks to justify theirrestrictions. That member state must provide the ground for justification, theimpact assessment of the restrictions and prove that the measures are nondiscriminatory and proportionate.

The most significant problems face with the free movement of goods are thetechnical barriers arising by the exceptions under European Union Treaty and the

judgments of the European court justice; in the forms of national regulations,standards for marketing goods and measures for the protection of public healthand safety. So, European Union member states must not exercise trade tactics by

avoiding regulating national laws or setting up standards for imports, exports orgoods in transit which can create the discriminatory restrictions. So, if allEuropean Union member states and the European court justice jointly workthrough these obstacles, then all conflicts can be resolve.

11

8/8/2019 European Lobbying

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/european-lobbying 12/12

Bibliography

John J. Barcelo III, Philippe Manin and Bernard Rudden. Materials for Introductionto European Union Law Course. Cornell-Paris I Summer Institute of Internationaland Comparative Law in Paris, 1999. 9.

Peter Oliver. Free Movement of Goods in The European Community. Third Edition.London Sweet and Maxwell, 1996. 17.

Paul Craig & Grainne De Burca. EU Law, Text, cases, and Materials. SecondEdition. Oxford University Press, 1998. 16.

12