Establishing an MPO Boundary: the MSA vs. UZA Standard

-

Upload

alexbond68 -

Category

Technology

-

view

2.566 -

download

2

Transcript of Establishing an MPO Boundary: the MSA vs. UZA Standard

Alexander Bond 1

The Merits of Using Metropolitan Statistical Areas to Delineate 1

Metropolitan Planning Organization Boundaries 2 3 4 5 Submission Date: 11/5/2009 6 7 Word Count: 6,649 (4,899 in text, 1 table, 6 figures) 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Corresponding Author: 15 Alexander Bond, AICP 16 Center for Urban Transportation Research 17 University of South Florida 18 4202 E. Fowler Ave, CUT 100 19 Tampa, FL 33620-5375 20 (813) 974-9779 21 Fax: (813) 974-5168 22 [email protected] 23 24

Alexander Bond 2

ABSTRACT 1 Since their inception in the 1970s, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) have been organized 2 around a geographic unit called an urbanized area (UZA). The complexity of MPO planning duties and 3 the makeup of metropolitan areas have increased over the past four decades. Also, a new delineation of 4 urbanity— the metropolitan statistical area (MSA) — has emerged since MPOs were first created. The 5 paper defines the geography and history associated with MPO designation, and presents evidence that the 6 MSA should replace the UZA as the standard for delineating an MPO’s boundary. Major arguments in 7 favor of the MSA standard include matching MPO boundaries to those of local and regional governments, 8 coordination of data, alignment with air quality conformity airsheds, and improved integration of land use 9 with transportation infrastructure. The paper also analyzes the number and size of MPOs that would be 10 created under an MSA standard. Current trends toward voluntary migration to the MSA standard are also 11 documented. Several policy recommendations are made, which may be useful to policy-makers and MPO 12 leadership. 13 14

Alexander Bond 3

INTRODUCTION 1 Since their inception in the 1970s, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) have been organized 2 around a geographic unit identified by the United States Census Bureau called an urbanized area (UZA). 3 New MPOs are designated for UZAs identified during each decennial (10-year) census. In addition, 4 existing MPO boundaries are changed when their constituent UZA boundaries are altered by the Census 5 results every ten years. 6

The complexity of MPO policy and planning duties has increased over the past four decades, and 7 so has the makeup of a metropolitan region. Meanwhile, the Office of Management and Budget has 8 created a new delineation of urban organization— the metropolitan statistical area (MSA). Perhaps it is 9 time to reexamine the geographic basis for designating MPOs, in particular the relative advantages of the 10 MSA over the UZA. With the pending expiration of SAFETEA-LU and an upcoming Census, this is an 11 excellent time to debate the merits of using the UZA versus the MSA to define metropolitan regions that 12 require the cooperative, comprehensive, and continuing (3-C) transportation planning process. This 13 paper presents evidence that MSAs should become the standard for designation of an MPO. 14 15 BACKGROUND 16 In order to discuss the relative advantages of each MPO designation standard, it is important to 17 understand the definitions being used. The UZA is developed by the US Census Bureau based on 18 information collected during each census. The MSA is produced by the Office of Management and 19 Budget (OMB), using information taken from the census and blended with information from other 20 sources, primarily the Department of Labor. The primary purpose of both geographies is to provide 21 statistical information for use by government agencies. A secondary purpose is to serve as the basis for 22 distribution of program funds that use a formula. A wide array of federal, state, and local executive 23 agencies use these urban definitions and delineations to allocate funding and implement regulations. 24 25 Urbanized Area 26 A UZA is a compact area that is entirely urban in character, defined as a contiguous area with more than 27 50,000 people and with a population density greater than 1,000 persons per square mile. The area that 28 meets the density definition is included in the boundary of the UZA, regardless of political boundaries. 29 The “building block” of a UZA is the census block group, which can be as small as one acre. Because the 30 level of analysis is so small, UZAs are often irregular in shape. Further, UZAs pay no attention to 31 political boundaries. Two UZAs cannot share a border, because such a condition would result in a single 32 contiguous geographic unit. According to the 2000 Census, there are 484 UZAs in the United States, 33 which cover just over 2% of the nation’s land area (1). The UZAs currently established in the United 34 States are shown in Figure 1. 35

Alexander Bond 4

1 FIGURE 1 Urbanized Areas in the United States- 2000. 2 3 Metropolitan Statistical Areas 4 Metropolitan statistical areas have a more complex definition. Counties serve as the “building blocks” of 5 MSAs. In order to be designated an MSA, the region must have at least one UZA to serve as the core of 6 the MSA (2). The county that contains the UZA is called the “core county” of the MSA. Additional 7 “outlying counties” that have high degrees of economic or social integration with the core are added to 8 the MSA. Outlying counties qualify for inclusion in the MSA if a) more than 25% of the employed 9 residents commute to the core county; or b) more than 25% of the jobs in the outlying county are held by 10 residents of the core county (3). The boundary of an MSA is coterminous with the county boundaries that 11 qualify for inclusion. Therefore, it is common for land area that is rural in appearance and character to be 12 included in the MSA. Two MSAs can share a border. MSAs can become quite large in land area—the 13 Atlanta MSA currently encompasses 28 counties. Most, however, encompass only one county. In New 14 England, the term ‘New England City and Town Area’ (NECTA) is substituted for MSA because 15 townships are the predominant local government type in those states. Figure 2 shows the 362 existing 16 MSAs in the United States. 17

The Office of Management and Budget–which is a part of the Executive Office of the President–18 is responsible for defining, creating, and modifying MSAs. The OMB issues annual updates to the list of 19 MSAs, but does not create new ones until after each Census (4). 20

Alexander Bond 5

1 FIGURE 2 Map of Metropolitan Statistical Areas- 2000. 2 3 MSA and UZA History 4 It is important to understand the history of how and when each geography was developed. The Seventh 5 Census (1850) was the first to allow regional administrators to delineate and collect data in geographies 6 smaller than the state level. This was the first data collection effort that laid the framework for 7 identifying urbanity, and data were amalgamated for some major municipalities and counties. The Ninth 8 Census in 1870 was the first to identify urbanized areas as distinct units free from political boundaries. 9 Over the next century, collection techniques were repeatedly improved upon, and definitions have 10 changed. Although the Census Bureau has reported “urbanized areas” for over 150 years, it has used the 11 modern definition since the Sixteenth Census in 1940 (5). 12

The concept of a metropolitan statistical area was first defined by the Office of Management and 13 Budget (OMB) in 1951 and has been modified six times since, most recently in 2003. The MSA took 14 almost two decades to reach its modern definition, and did not gain wide acceptance until the 1980s (6). 15

MPOs were created by the 1973 Federal Aid Highway Act. In 1973, the MSA was not a well-16 recognized or well-developed concept. The UZA, however, had been in common use for many decades. 17 The authors of the legislation designed MPOs to be situated around the only geographical representation 18 of urbanity available at that time—the UZA. Today, we have both the UZA and the MSA to choose from. 19

In order to visualize the difference between MSAs and UZAs, Figure 3 overlays the MSAs in 20 Florida with the UZAs in the state. Each MSA is shown with a different color, but the UZAs are shown 21 in uniform yellow. 22

Alexander Bond 6

1 FIGURE 3 MSAs and UZAs in Florida- 2008. 2 3 4 Metropolitan Planning Organizations 5 A Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) is a regional transportation infrastructure planning agency. 6 The Federal government requires MPOs to perform transportation planning in all areas with more than 7 50,000 people. Agency operations and policy are directed by a board of local elected and appointed 8 officials. 9

MPOs were first mentioned in the 1962 Federal Aid Highway Act, but were not constituted as 10 official agencies until the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1973. The contemporary MPO planning process 11 and organizational structure was put in place by the Intermodal Surface Transportation Act (ISTEA) in 12 1991. MPOs were established in response to an outcry from local governments about of the lack of a 13 local voice in the route choices of major Federal-aid freeways, such as the Interstate Highway System (7). 14 The chief purpose of the MPO is to plan and program transportation improvements. The process is 15 founded on a metropolitan transportation plan, which must look at least 20 years into the future. The 16 projects identified by the MPO in the metropolitan transportation plan usually do not have a construction 17 timeframe, and act more as a pool of approved projects to be built over the next 20-plus years. The MPO 18 selects projects from the metropolitan transportation plan for inclusion in a four- to five-year 19 Transportation Improvement Program (TIP). The TIP sets a timetable for construction. The projects in 20

Alexander Bond 7

the MPO Transportation Improvement Program must be included in the State Transportation 1 Improvement Program (STIP). A project’s presence in the STIP enables contracts to be issued for actual 2 construction. 3

Over time, the role of MPOs has expanded to include important issues like protection of civil 4 rights, preservation of cultural resources, safety controls, proactive enforcement of the National 5 Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), and control of air pollution under the Clean Air Act. Failure to 6 establish an MPO or execute the prescribed planning program will result in a withholding of Federal 7 highway and transit dollars for that region (8). 8

The wide variety of MPO organizational structures and boundaries presents substantial 9 difficulties when attempting to improve or standardize the MPO planning and programming process. The 10 Federal government, research institutions, and contractors are unable to craft “one-size fits all” tools, 11 software, and planning approaches because MPOs are all so different from each other. Further, MPOs 12 will have difficulty adjusting to new duties (such as greenhouse gas reduction) if MPOs are not made to 13 more closely resemble each other. 14 15 MPO Designation 16 The process of establishing an MPO is called “designation.” Every ten years, the Census Bureau issues a 17 list of UZAs. All of the land area inside a UZA must be covered by an MPO. The MPOs in each state are 18 designated by agreement between the governor of the state and local governments representing 75% of 19 the population in the MPO area, including the largest municipality. The MPO planning boundary is 20 expected to cover land that is forecast to become urbanized over the next twenty years. A single MPO 21 can cross state lines. In fact, about 14% of all MPOs operating today are multi-state (9). Once 22 designated, the MPO does not need the Governor’s approval to expand its boundary unless a new UZA is 23 created outside the planning area. 24

Federal law does not describe the organizational composition of an MPO. Nor does it prescribe the 25 way MPOs are organized to cover the UZAs in the state. Over the decades, a wide variety of MPO 26 boundaries have been established. Little research exists on the optimal MPO configuration. Figure 4 27 illustrates three of the many conditions allowable under current law. Maps are courtesy of the Florida 28 MPO Advisory Council: 29

• A common type of MPO boundary can be seen in the map of the Gainesville (FL) MTPO, which 30 is map B in Figure 3. A small portion of land area outside the UZA is included in the MPO planning 31 boundary. This is land expected to become urbanized in the next twenty years. 32

• A single MPO can cover more than one UZA, as demonstrated in map A. In this case, the 33 Volusia (FL) MPO covers the entirety of both the Deltona UZA and the Daytona Beach-Port Orange 34 UZA. 35

• A single UZA may be covered by more than one MPO, as shown in map C. The Broward (FL) 36 MPO covers only part of the Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach UZA. The rest of the UZA is 37 covered by two other MPOs (Miami-Dade MPO and Palm Beach MPO), because all land area in a UZA 38 must be inside an MPO planning area. 39

Alexander Bond 8

1 FIGURE 4 Example MPO boundary maps. 2 3 ANALYSIS 4 The past several decades have seen a significant expansion of cities, rapid suburbanization, new planning 5 requirements on MPOs, and new ideas about the practice of transportation planning. All of these 6 developments make the MSA a more logical basis for MPO designation. Below are several arguments in 7 favor of MPO designation under the MSA standard. 8 9 Coterminous with Local and Regional Governments 10 UZAs bear no relation to the boundaries of local government. MSAs by definition must end at county 11 borders. Being coterminous with the boundaries of local governments provides MSAs with certain 12 advantages over UZAs as MPO boundaries. 13 14 Uniform Data 15 One of the most compelling arguments in favor of an MSA standard is the synchronization and 16 compatibility of datasets and information standards. The MSA is the most commonly used geography for 17 government data collection and distribution of grants from government programs. A 2004 Government 18 Accountability Office (15) study of thirty-five major Federal funding programs intended to assist cities 19 used formulas based on MSAs. None used UZAs in their formulae. The MSA is used to amalgamate and 20 publish statistics from the Departments of Commerce, Education, Labor, Justice, Transportation, 21 Treasury, and Housing and Urban Development. The UZA is only used for a narrow set of data produced 22 by the Departments of Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and the Census Bureau. Under 23 an MSA standard, most of the data produced by the government and private sector will automatically 24

Alexander Bond 9

match the MPO’s planning area, facilitating quick and simple calculations during the planning process. 1 Currently, MPOs must expend considerable effort to break down data into the correct geography. 2

Travel demand models depend heavily on data. Since 1973 creation of MPOs, engineers and 3 planners have developed and refined a number of tools to predict future demand on the transportation 4 system. These complex systems often have to look well beyond the UZA in order to forecast 5 transportation demand. For example, the model needs to predict inter-regional trips, which requires 6 volume input for roadways that lie far beyond the UZA boundary. An MSA-sized MPO would do a 7 better job of supporting travel demand modeling because more lane miles that are not “urban” would 8 automatically be included in the planning area, and thus, the urban travel demand model. 9

Beyond travel demand modeling, transportation planning in general is better served with a MSA-10 sized MPO. The MPO can take a stronger position in transit visioning, since the planning area would 11 cover urban, rural, on-demand, and regional transit system service areas. The MPO would also be in a 12 more powerful position to influence growth management if the planning area boundary was larger. 13 Finally, Federal transportation planning money could be leveraged into improved transportation planning 14 at the local level. 15 16 Land Use Coordination and Growth Management 17 It is generally accepted planning practice that land use and transportation need to be better integrated (10). 18 Further, growth management efforts are significantly strengthened if transportation infrastructure is used 19 as a growth management tool to combat urban sprawl (11). In most states, land use is the sole 20 responsibility of local governments. MPOs are not authorized to govern land use. Since the MPO 21 planning area is not required to match a local or regional land use planning area, integrating transportation 22 and land use can be a difficult exercise. By using an MSA designation standard, the MPO would produce 23 a transportation plan for an entire county or group of counties. The information from the MPO plan could 24 be directly incorporated into each county’s land use plan. Through an iterative process over several plan 25 cycles, land use and transportation would become more closely integrated. 26 27 Political Constituencies 28 If MPO boundaries are coterminous with local government boundaries, then the constituencies of MPO 29 board members would lie entirely within the MPO area. Figure 5 demonstrates an example of this 30 situation using the county commission districts of Escambia County, FL (Pensacola). The approximate 31 MPO boundary line is shown bisecting District 5. A small area of District 5 lies inside the MPO, but it 32 also covers a vast non-MPO area in the northern part of the county. The commissioner serving this 33 district has many constituents who do not live in the MPO area, and may not live in the MPO area 34 himself. This can create a conflict of interest for that official. If the MPO extended to the county 35 boundary–as would be the case under an MSA standard—the Commissioner of District 5 will represent 36 all of his constituents on the MPO board. 37 38

Alexander Bond 10

1 FIGURE 5 County commission districts of Escambia County, FL. 2 3 Councils of Government 4 In 1959, President Eisenhower established the Advisory Council on Intergovernmental Relations (ACIR), 5 which oversaw the transition of traditional state-based programs toward program implementation at the 6 regional level. The most lasting result of ACIR’s effort was the establishment of Councils of Government 7 (COGs), which have a variety of names like Associations of Government, Regional Councils, or Planning 8 and Development Commissions. The 500-plus COGs operating today have become a standard component 9 of government all across the United States (12). Many COGs administer programs that must be treated 10 regionally, such as affordable housing, environmental protection, emergency management, or local 11 transportation like recreational trails and paratransit. Some COGs also function as MPOs. Many, if not 12 most, are organized around regions that closely resemble MSAs. 13

If MPOs were designated around MSAs, their boundaries would be more similar to COGs. Major 14 advantages of having a similar boundary include data sharing, intergovernmental coordination, and the 15 introduction of non-transportation information into the MPO process. Some programs commonly 16 administered by COGs could help inform and influence the transportation planning process, such as 17 housing, water quality, and emergency preparedness. The COG should not be forced to become the 18 MPO, nor should MPOs be incentivized to become hosted by the COG. Such decisions can only be made 19 through intergovernmental political decision-making in each region. COGs and MPOs do not need to 20 merge in order to get these benefits—they just need similar borders so that information can flow freely. 21 22 Air Quality Conformity 23 A regulatory and funding system known as National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) were 24 established by the Clean Air Act of 1990. Governors are required under 45 USC 7407 (D)4(a)iv to 25 submit to the Environmental Protection Agency a list of regions that do not meet ozone, carbon monoxide 26 and particulate matter standards of air quality. The default size of a nonattainment area is a metropolitan 27

Approximate MPO Boundary

Alexander Bond 11

statistical area. However, the governor is able to alter that boundary by documenting his reasons to the 1 EPA (14). From this section of law, it is clear that Congress intended for air quality to be measured and 2 solutions administered at the MSA level. However, much transportation planning is required to take 3 place at the much smaller UZA scale. 4

Congress charged MPOs with developing transportation solutions to combat poor air quality. 5 Beginning with ISTEA, and continued in TEA-21 and SAFETEA-LU, the Congestion Mitigation and Air 6 Quality (CMAQ) program has provided transportation funding for regions that are in NAAQS non-7 attainment or maintenance status. MPOs are the agency in charge of the planning and programming of 8 about $1.7 billion per year in CMAQ money. As of July 2009, fifty-five air quality regions are in 9 nonattainment for ozone standards, and thirty-seven for particulate matter standards. Further, standards 10 for ozone will tighten with the implementation of new rules by the end of 2011, causing more regions to 11 fall into nonattainment. Air quality is a serious problem, and transportation planning is a big part of the 12 solution. However, there is often a mismatch between an MPO planning area arranged around a UZA and 13 the air quality airshed identified by MSA. This can complicate the integration of regional transportation 14 planning and air quality planning, particularly in locales that only recently were found to be in 15 nonattainment. 16 17 Fewer MPOs, Better Coverage 18 Some have criticized the large number of MPOs in existence, and doubt the ability of smaller MPOs to 19 fully perform the tasks required by Federal law (15). Using MSAs as the standard, more of the US 20 population would be included in an MPO area, while simultaneously limiting the total number of MPOs. 21 See table 1 for a summary of the UZAs and MSAs from the 2000 Census. There are 484 UZAs in the 22 country, which have been organized into 385 MPOs. UZAs cover approximately 63% of the population. 23 Meanwhile, 362 MSAs cover 80% of the American public. 24

It is unknown how many MPOs would be organized from among the MSAs, but the number 25 would certainly be fewer than are found today. Because MSAs include entire counties, there are 26 opportunities for only one MPO to be formed where there are currently two or more. For example, the 27 borders of the four-county Orlando-Kissimmee MSA currently have two MPOs operating in it 28 (METROPLAN Orlando and Lake-Sumter MPO). Under the MSA standard, the entire MSA would 29 function as only one MPO. This assumes that new regulations would require only one MPO per MSA. 30 31 TABLE 1 Number and Population in MSAs and UZAs 32 Geography Type Number Percent US

Population Urbanized Area 484 63% Metropolitan Statistical Area

362 80%

33 Current Trends in MPO Boundary Expansion 34 A change in Federal law is not needed for individual MPOs to reap the benefits of expanding the MPO 35 boundary. It is important for MPO leadership to understand that current law allows nearly complete 36 freedom in setting the agency’s planning area. The boundaries of an MPO can be expanded at any time if 37 local governments in the area agree to the change. A more formal process of re-designation can take 38 place after each Census. Therefore, MPOs already have the capability of matching their planning area 39 boundary to the edge of the MSA, and all of the advantages discussed in this paper can be achieved by 40 taking that action. 41

Many MPOs have already expanded well beyond the required area. Twenty-seven percent of 42 MPOs in the US have more than one UZA in their planning area. More than 42% encompass more than 43 one county (9). Larger MPO planning areas suggest that the intergovernmental political process in that 44 region has concluded that the area functions as a single transportation region and should have a single 45 MPO. Clearly, many regional already see a benefit in an expanded planning area. 46

Alexander Bond 12

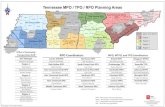

Figure 6 shows the planning area boundaries of MPOs currently operating in the United States. A 1 visual inspection of the map reveals that MPO boundaries are much larger than the UZA, and also extend 2 beyond the expected 20-year growth boundary. The size and shape of MPO boundaries have more in 3 common with MSAs than UZAs. This is particularly true in Florida, California, Pennsylvania, the great 4 lakes region, and the northeast corridor. When the two maps are compared, it is clear that MPO 5 boundaries already are more similar to MSAs than UZAs. 6 7

8 FIGURE 6 A comparison of MSA and MPO boundaries. 9 10

One reason some MPOs extend their planning area is to match the boundary of their host agency. 11 Some MPOs forge hosting partnerships with other agencies because of information gathering, cost 12 savings, or political advantages. According to a recent study, approximately 68% of MPOs were hosted 13 by another agency. The most common hosting relationship is with Councils of Government or similar 14 regional general-purpose government agencies. Approximately 24% of all MPOs in the United States are 15 hosted at a COG. Another 16.5% of MPOs are hosted by a County Government (9). 16

Alexander Bond 13

1 MODIFICATIONS TO THE MSA 2 MSAs are by definition quite large. Most include stretches of land that is rural in character, and this is 3 one of the major drawbacks of using the MSA standard. Fortunately, there are at least two modifications 4 to the MSA standard that would help alleviate this problem. 5

The first policy alternative is to use only “core” MSA counties. When the Office of Management 6 and Budget assembles an MSA, it begins with a core county (or sometimes counties), which is the county 7 that has 50,000 or more people and a dense core. Then additional counties are added. MPOs could be 8 required to cover only the core county, while making outlying counties optional. This system would 9 allow rural outlying counties to be omitted from the MPO planning area. For example, the Gainesville 10 MSA’s core county is Alachua County, FL (pop. 217,000). The MSA also includes rural Gilchrist 11 County (pop. 14,437) as an “outlying” county because more than 25% of the residents work in Alachua 12 County. Under this policy alternative, only Alachua County would be required to be in the MPO, while 13 Gilchrist County would be optional. 14

There are some single-county MSAs that would have broad stretches of rural land area. Some 15 counties are exceptionally large in land area, particularly in mountain west states. Since MSAs are 16 coterminous with counties, these very large counties could turn into very large MPOs. An alternative 17 could be for the MPO to “opt out” Census tracts that have a very low population density. In order to opt 18 out, the MPO would need to go through some sort of approval process to prove the administrative 19 purpose for excluding land area. For example, the Flagstaff MSA (pop. 127,000) is comprised only of 20 Coconino County, Arizona. But Coconino County’s land area of 18,661 square miles makes it larger than 21 nine US states. This is an extremely large area to effectively maintain an MPO planning process. Wide 22 portions of Coconino County are desert with a population density below 10 people per square mile. 23 Under this alternative, the Flagstaff MPO could apply to the USDOT to exclude from its planning area all 24 census tracts with a population density below 10 people per square mile. The application process would 25 need to be laid out specifically in regulation. 26 27 CONCLUSION 28

It is very important for MPO designation to be based on a third-party definition. Initial 29 designation of an MPO can be a contentious issue that encroaches on the traditional areas of responsibility 30 of several groups. State Departments of Transportation lose considerable project selection authority, and 31 the balance between municipalities and the county can be upended. Having a neutral third party 32 determine the boundary is a simple way to ensure that the legislative intent of MPO creation is met. Since 33 the establishment of MPOs, the neutral party has been the Census Bureau drawing the UZA. An MSA 34 drawn by the Office of Management and Budget also fits the definition. Both are neutral third parties and 35 draw a district with a clearly defined geography. 36

MSAs offer several advantages over the UZA for MPO designation. They are, by definition, 37 coterminous with local government and regional governments, and match closely with air quality 38 conformity areas. Further, more of the United States is covered by an MPO while at the same time 39 limiting the number of agencies being operated. Many MPOs already possess planning areas that more 40 closely resemble MSAs than UZAs. The designation standard should be included in the successor 41 legislation to SAFETEA-LU and put into effect following the results of the OMB’s revised list of MSAs 42 based on the 2010 Census. 43

Establishing MPO planning areas by MSA could have powerful impacts on transportation 44 planning because of uniformity and standardization. After four decades of use, the time is right for an 45 honest reevaluation of the MPO and the scale of the metropolitan planning process. The MSA is a more 46 accurate representation of modern MPOs and metropolitan transportation planning, and it should be given 47 strong consideration as the basis for MPO boundary delineation. 48

Alexander Bond 14

REFERENCES 1 (1) Environmental Protection Agency, “Storm Water Phase II Final Rule: Urbanized Areas: Definitions 2 and Descriptions.” Document Number EPA-833-F-00-004, Issued December 2005. 3 4 (2) Bureau of the Census. “Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas.” Accessed July 14th, 2009. 5 Available from: http://www.census.gov/population/www/metroareas/aboutmetro.html 6 7 (3) Federal Register: Volume 65, Number 249 (December 27, 2000) pp. 82228-82230. 8 9 (4) Gauthier, Jason, “Measuring America: The Decennial Censuses from 1790 to 2000” United States 10 Census Bureau, September 2002. 11 12 (5) Frey, William and Zachary Zimmer. “Chapter 2: Defining the City.” From Handbook of Urban 13 Studies, Ronan Paddison, ed. Sage Publications, 2001. 14 15 (6) Office of Management and Budget Executive Order No. 10253 (June 11, 1951) 16 17 (7) Solof, Mark. “History of Metropolitan Planning Organizations.” Newark, NJ: North Jersey 18 Transportation Planning Agency. 1998. Available from: 19 http://www.njtpa.org/Pub/Report/hist_mpo/documents/MPOhistory1998_000.pdf 20 21 (8) Federal Highway Administration/Federal Transit Administration Transportation Planning Capacity 22 Building Program, “The Transportation Planning Process: Key Issues.” Document #FHWA-HEP-07-039. 23 September 2007. Available from: http://www.planning.dot.gov/documents/BriefingBook/bbook_07.pdf 24 25 (9) Bond, Alexander and Jeff Kramer, “Staffing and Administrative Capacity of Metropolitan Planning 26 Organizations.” Federal Highway Administration Contract # DTFH61-08-C-00021. 2009 27 28 (10) Ewing, Reid and Robert Cervero. “Travel and the Built Environment: a Synthesis,” Transportation 29 Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, Volume 1780. 2001. 30 31 (11) Nicholas, James C., and Ruth L. Steiner. 2000. "Growth Management and Smart Growth in 32 Florida." Wake Forest Law Review 35:645-670. 33 34 (12) National Association of Counties, “The History of County Government.” Accessed 7/10/2009. 35 Available from: http://www.naco.org/Content/NavigationMenu/About_Counties/History_of_ 36 County_Government/Default983.htm 37 38 (13) Weitz, Jerry and Ethan Setzer. “Regional Planning and Regional Governance in the United States 39 1979-1996.” Journal of Planning Literature, Volume 12, Number 3, pp. 361-392. 1998. 40 41 (14) Transportation Research Board. “Special Report #264: The Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality 42 Program—Assessing 10 Years of Experience.” National Academy Press: Washington, DC. 2002 43 44 (15) Turnbull, Katherine, Ed. Transportation Research Board Conference Proceedings Number 39: The 45 Metropolitan Planning Organization: Past, Present, and Future. 2006. Available from: 46 http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/conf/CP39.pdf 47 48 (16) Government Accountability Office, “Metropolitan Statistical Areas- New Standards and Their 49 Impact on Selected Federal Programs.” Report to the House Committee on Government Reform, June 50 2004. Available from: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04758.pdf 51