Emergency jc presentation1

-

Upload

drrudradeo-kumar -

Category

Health & Medicine

-

view

72 -

download

0

Transcript of Emergency jc presentation1

• Maxillofacial and neck trauma exposes patients to life threatening complications such as airway compromise and hemorrhagic shock

• physician has to consider following aspects to secure the airway-

• the nature of the trauma and its effect on the airways, • potential difficulties in mask ventilation or endotracheal

intubation,• possible trauma of the cervical spine• the risk of regurgitation and aspiration of gastric

contents, • significant bleeding that precludes view of airway

anatomy and may cause circulatory deterioration, and

• The type of maxillofacial operation that is to be done and whether the oral cavity needs to be empty for performing the procedure and closed with MMF at the end of surgery

• conditions require not only a rapid recognition and management but also a strong interplay between surgeons, anesthesiologists and other relevant medical personnel.

• The combined occurrence of coagulopathy, hypothermia, and acidosis (“the lethal triad”) further contributes to the poor prognosis of severely exsanguinating trauma patients

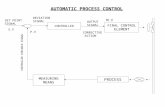

• New strategies termed DCS and DCR have gained popularity in the management of injured patients

• DCS can be defined as the rapid initial control of hemorrhage and contamination, temporary wound closure, resuscitation to normal physiology in the ICU and subsequent reexploration and definitive repair following restoration of normal physiology

• DCR, defined as nonsurgical strategies utilized to prevent or reverse the effects and outcomes of “lethal triad”, consists mainly of hypotensive (permissive hypotension) and hemostatic (minimal use of crystalloid fluids and utilization of blood and blood products) resuscitation

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

Damage control strategy are mainly related to:

• significant bleeding requiring massive transfusion, • severe metabolic acidosis(pH< 7.30), • hypothermia (T < 35.8 °C)• estimated operating time > 90 min,• coagulopathy • lactate > 5 mmol/l

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

According to Hutchison et al., there are six specific situations associated with maxillofacial trauma, which can adversely affect the airway.

• Posteroinferior displacement of a fractured maxilla parallel to the inclined plane of the base of the skull may block the nasopharyngeal airway.

• bilateral fracture of the anterior mandible may cause the fractured symphysis and the tongue to slide posteriorly and block the oropharynx in the supine patient.

• Fractured or exfoliated teeth, bone fragments, vomitus, blood, and secretions as well as foreign bodies, such as dentures, debris, and shrapnel, may block the airway anywhere along the oropharynx and larynx.

• Hemorrhage from distinct vessels in open wounds or severe nasal bleeding from complex blood supply of the nose may also contribute to airway obstruction.

• Soft tissue swelling and edema which result from trauma of the head and neck may cause delayed airway compromise.

• Trauma of the larynx and trachea may cause swelling and displacement of structures, such as the epiglottis, arytenoid cartilages, and vocal cords, thereby increasing the risk of cervical airway obstruction

• A high index of suspicion, a meticulous physical examination, and close observation of the patient may assist in the early detection of such situations and facilitate proper and timely management in order to avoid future complications.

• Once airway management has been completed and hemorrhage is controlled at all sites, the patient should have a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the head and neck with i.v. contrast material, in order to demonstrate the vascular structures surrounding the injury sites and provide detailed information on the type and extent of the trauma, for definitive management of bone and soft tissue injuries.

EARLY AIRWAY MAINTENANCE• According to the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS)

recommendations for managing patients who sustained life threatening injuries, airway maintenance with cervical spine immobilization is the first priority

• Airway management problems are not confined to the early stages of the “triage process” or to the resuscitation of the patient Morbidity and mortality of in-hospital trauma patients often result from critical care errors, with airway management being the most common .

• Gruen et al. studied the causes of death of 2594 trauma patients in order to identify the error patterns and found that 16% of inpatient deaths were caused by failure to intubate or failure to secure or protect the airway.

• The first action in the process of early airway management is preoxygenation using non rebreathing mask, which may prolong the time interval up to hypoxemic state.

• Endotracheal intubation is the gold standard procedure to secure the airway in trauma patients. It is to be performed via the oral route with a rapid sequence induction and a manual in-line stabilization maneuver, in order to decrease the risk of pulmonary aspiration and take into account a potential cervical spine (C-spine) injury

• Endotracheal intubation is expected to be difficult in maxillofacial trauma patient

. • The challenge in performing the intubation arises mainly from a

difficulty in viewing the vocal cords using conventional direct laryngoscope. The oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx may be filled with blood, secretions, soft tissue, and bone fragments, all of which preclude a good view of the vocal cords.

• Regarding mask ventilation, mask ventilation is problematical in the patient with maxillofacial trauma because the oral cavity and/or oropharynx’s anatomy could be disarranged by the trauma and/or blocked by bleeding. Thus, the ventilation mask cannot be properly fitted to the face for effective mask ventilation.

• Injured airway may prevent efficient air transfer from the mask to the lungs

PROBLEMS OF ANTICIPATED DIFFICULT INTUBATION AND MASK VENTILATION

FULL STOMACH-

• patient with maxillofacial trauma must be assumed to have a “full stomach” because digestion stops after the trauma

• such patients often bleed from the upper airway, blood is swallowed and accumulates in the stomach and the risk of regurgitation and aspiration is high.

• In order to diminish such risks, evacuating the contents of the stomach through the nasogastric tube before proceeding with airway management is recommended.

• However, insertion of a nasogastric tube in a confused, uncooperative, sometimes intoxicated patient who has sustained a facial injury may, by itself, trigger vomiting.

• In addition, it is relatively contraindicated in cases with a possible fracture of the base of skull.

• Formerly it was accustomed to use Sellick’s maneuver, in order to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration.

• The Sellick’s maneuver is a technique in which the esophagus is occluded by applying pressure on the cricoid cartilage

• Maneuver may significantly hamper endotracheal intubation because the laryngeal view is worsened . In addition, its efficacy in preventing aspiration is questionable , and in some cases it may lead to ruptured esophagus.

C SPINE INJURY

• patient with a supraclavicular injury is considered to have a C-spine injury, until proven otherwise by imaging

• Between 2–4 % of patients suffering from maxillofacial fractures resulting from blunt trauma, have concomitant cervical spinal fractures, and 10–12 % have cervical ligamentous injuries

• At the time of intubation, the anesthesiologist’s assistant performs “in-line stabilization” in order to support the head and neck in place and prevent neck movement throughout the procedure

• several studies indicate that direct laryngoscopy and intubation are unlikely to cause clinically significant neck movements.

• On the other hand, “in-line stabilization” may not always immobilize the injured segments effectively.

• In addition, “in-line stabilization” worsens the laryngoscopic view which may, in turn, worsen the outcome in traumatic brain injury by delaying endotracheal intubation and causing hypoxia

• Using a video laryngoscope, instead of a conventional laryngoscope with a Macintosh blade, may be beneficial for intubating patients whose neck position needs to be in a neutral position and their cervical spine requires immobilization

MAXILLOFACIAL BLEEDINGIn patients with major maxillofacial trauma, severe uncontrolled bleeding is possible, especially in trauma that involves more than two thirds of the face, “panfacial trauma.” Hemorrhage affects the patient’s condition and prognosis in several ways:• blood in the oral cavity often excludes mask ventilation• it may preclude good view of airway anatomy, thus making

intubation very difficult• significant hemorrhage may cause circulatory compromise that

may be fatal• coagulation may deteriorate due to massive blood transfusion and • the surgical field conditions during bleeding are less than optimal

for operating.

EMERGENCY SITUATIONS

• Managing the airway in an emergent situation poses additional difficulty because the time to accomplish the task is short and the patient’s condition may deteriorate quickly.

• The performance of urgent or emergent intubation is associated with remarkably high complication rates, which may exceed 20% .

• These high rates are due to several factors, which include repeated intubation attempts, the need to perform direct laryngoscopy without muscle relaxation, and the lack of experience of the operator.

• The main complications that may occur at that time are hypoxemia, aspiration, esophageal intubation, esophageal tear, alterations in the heart rate, new onset cardiac dysrhythmias, and cardiac arrest.

PERSONAL EXPERIENCE• In emergency situations, the care of acute trauma patients is

provided by individuals who are often not experienced, the “inverse care law”

• The responsibility for acute airway management often falls into the hands of nonanesthesiologists

• Walls et al. reported that anesthesiologists performed only 3% of the intubations, and the remaining 97% of the intubations were performed by emergency physicians (87%) and physicians from other specialties (10%).

Approach to the Airway of the Patient with Maxillofacial Trauma

Airway Evaluation and Preparation. • Airway evaluation of a patient with maxillofacial trauma should be

done thoroughly and as quickly as possible because the patient’s airway is compromised

At this time we ask the following questions.• Is the patient conscious? If so, the use of sedatives or analgesics

should be done cautiously, if at all, because the airway can be lost following injudicious use of such drugs .

• Is the patient breathing spontaneously? If so, preoxygenation is mandatory. According to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Practice Guidelines for management of the difficult airway, spontaneous breathing should be preserved in patients with anticipated difficult endotracheal intubation

• Is the patient hypoxemic? If preoxygenation is possible and effective in improving patient’s oxygenation then it is to be done with a face mask. If preoxygenation is not possible then ventilation is to be pursued at that time by the caretakers

• What is the extent, the details, and the anatomy of the injury? Are the bony structures of the face involved? In cases of massive injuries, mask ventilation may be impossible

• For quick and easy identification of factors that may predispose difficult intubation or ventilation, one may use the LEMON assessment .

• The components of this assessment are as follows: • Look externally to detect difficult airway predictors, such as short neck and evaluate mouth opening and thyromental distance,

• Is there a limitation of mouth opening? If so, is pain the cause of the limitation and can the mouth be opened wider after analgesia

• If the limitation of mouth opening is caused by a TMJ injury, sedation will not improve mouth opening and may even worsen the scenario.

• Are there additional predictors for difficult endotracheal intubation, such as obesity?

• What are the requirements of the upcoming maxillofacial surgery? Does the oral cavity need to be completely free of any medical devices for performing the surgery?

• Initial casualty assessment determines whether the airway is patent and protected, and if breathing is present and adequate.

• Normal speech may suggest that the airway is patent, at least for the

time being, while wheezy breathing usually indicates partial airway obstruction by the tongue and hoarseness or stridor usually suggests a laryngeal cause for airway obstruction.

• The oral cavity must be thoroughly cleared, visualized and inspected under proper lighting, taking care not to extend or rotate the neck.

• Blood, loose and fractured teeth, foreign bodies, dirt and mucus are meticulously removed.

• The midface and mandible are inspected for structural integrity and the anterior neck inspected for penetrating wounds.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• Crepitus upon palpation of the neck may suggest airway injury or communicating pneumo mediastinum.

• Diminished breath sounds on auscultation may result from atelectasis, pneumothorax, hemothorax or pleural effusion

• Wheezing and dyspnea may imply lower airway obstruction, agitation may represent hypoxia at tissue level and cyanosis indicates arterial blood hypoxemia.

• Suprasternal, supraclavicular or intercostal retractions may be indicative of respiratory muscle fatigue.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• Clearing the airway is the first step in airway management.

• The chin-lift with head-tilt maneuver opens the airway, but should be avoided in any patient with a potentially unstable cervical spine injury.

• The jaw thrust without head-tilt maneuver may be performed while maintaining cervical spine alignment and should be utilized in such instances.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

AIRWAY CONTROL AND BREATHING SUPPORT IN MAXILLOFACIAL TRAUMA

• Oral or nasopharyngeal airway devices can establish a temporary nonsurgical secure airway in a spontaneously breathing patient, but they do not provide definitive airway protection against aspiration.

• Nasal airways should not be placed in cases of midface and craniofacial injuries, as they can inadvertently be introduced into the cranial vault in skull base injuries.

• commonly used in semiconscious patients who do not tolerate the oropharyngeal airway, or when the oropharyngeal airway is obstructed (trismus, wiring of teeth etc.).

• In a conscious patient with an active gag reflex it is contraindicated, as it may stimulate vomiting, laryngospasm and agitation.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• Effective approach to airway management with possible cervical spine injuries is rapid sequence intubation with inline spinal immobilization.

• Pharmacologically paralyzing the patient reduces the risk of patient movement during intubation attempts, improves airway visualization, and facilitates subsequent endotracheal intubation

• Alternative airway securing system (surgical airway) should be ready at hand before paralyzing the patient in the event that endotracheal intubation is not possible, but must be used only as last resort

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• A definitive airway requires an endotracheal tube (ETT) or tracheostomy tube in the trachea with the cuff inflated, secured in place, and attached to an oxygen-enriched ventilation device.

• Reasons for securing a definitive airway include:• Failure of ventilation or oxygenation• inability to maintain or protect an airway • potential for patient status deterioration• facilitation of patient management during evacuation and

transport.

• Cardiac monitoring, blood pressure monitoring and pulse oximetry (as well as end-tidal CO2 monitoring, if available) are mandatory for all patients.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

RAPID SEQUENCE INTUBATION

• The patient should be preoxygenated first, followed by administration of an induction agent and a rapidly acting neuromuscular blocking agent to induce a state of unconsciousness and paralysis.

• Assistant should apply cricoid pressure to prevent passive regurgitation of gastric contents, until the ETT has been placed

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

AWAKE ENDOTRACHEAL INTUBATION• Requires liberal topical airway anesthesia and sedation prior to

intubation. This permits patent airway reflexes and spontaneous breathing in a patient with a distorted airway caused by displaced mandibular fractures and soft tissue edema.

CRASH ENDOTRACHEAL INTUBATION • Immediate endotracheal intubation without the use of medications. • It is indicated in patients with respiratory arrest, agonal

respirations, or deep unresponsiveness.• Advantages are technical ease and rapidity, and the disadvantages

are potential increase in intracranial pressure, as well as emesis and aspiration.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

CONFIRMATION OF ENDOTRACHEAL TUBE PLACEMENT • As inadvertent intubation of the esophagus may occur during airway

management, and may result in patient death.• Proper ETT placement detection methods include: clinical assessment,

auscultation over the lungs, aspiration of air through the tube, pulse oximetry, end-tidal CO2 level measurement, ultrasonography and chest radiography.

SURGICAL AIRWAY MANAGEMENT • Despite active bleeding and gaping facial wounds, the fastest and most

straightforward technique to establish a definitive airway is often direct laryngoscopy and oral endotracheal intubation.

• If direct laryngoscopy to achieve endotracheal intubation for immediate airway fails, a cricothyroidotomy is an expedient technique to establish a definitive airway.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• In an emergency situation, surgical cricothyroidotomy is preferred to a tracheotomy because it is more rapidly executed, the distance from the skin is shorter (10 mm vs. 20–30 mm) and the risk of violating the vascular thyroid isthmus (resulting in hemorrhage) is lower

THE DIFFICULT AIRWAY • The inability to bag-valve-mask ventilate a patient is a

contraindication to administering a muscle paralyzing agent (rapid sequence induction).

• The use of ketamine with atropine may facilitate direct laryngoscopy. • A surgical cricothyroidotomy under ketamine anesthesia is another

alternative as fiberoptic laryngoscopy. When possible preoxygenation with 100 % highflow oxygen should be performed for several minutes before airway maneuvers. Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

Airway Management Devices. Airway Devices That Enable an Indirect View of the Vocal Cords

• FIBER-OPTIC INTUBATION(FOB)- Use of FOB is somewhat impractical in patients with maxillofacial trauma.

• Blood, vomitus, and secretions in the patient’s airway may preclude vision by fiber-optic instruments, an accomplishing effective local anesthesia in the injured regions is difficult.

• Furthermore, the patient’s cooperation is essential for such an approach, and this cooperation is not easy to obtain in the trauma patient.

THE VIDEO LARYNGOSCOPE. The video laryngoscope, such as GlideScope video laryngoscope, enables an indirect view of the epiglottis and the vocal cords

• the video laryngoscope may be useful in selected patients with soft tissue swelling at the base of the tongue, and in those patients in whom disruption of the normal anatomy precludes locating the epiglottis.

BLINDLY PLACED AIRWAYMANAGEMENT DEVICES. SUPRAGLOTTIC AIRWAY DEVICES (SAD), such as the LMA and its several diverse variations, are very important devices for managing the difficult airway

• For airway management of the trauma patient, the SAD is placed blindly in the oropharynx and its successful placement requires minimal experience

• SADs do not provide a definitive airway and can be displaced when the patient with an SAD is moved and transferred.

• When the definitive surgery is to be performed, the SAD may be replaced by an endotracheal tube or, alternatively, into a tracheostomy.

THE COMBITUBE is another airway management device that is inserted blindly into the oropharynx.

• insertion of Combitube can be associated with serious injury to the upper airway and digestive tract, such as esophageal laceration and perforation, tongue edema, vocal cord injury, tracheal injury, aspiration pneumonitis, and pneumomediastinum.

• THE SURGICAL AIRWAY. The surgical airway is considered to be the last option in airway management

• Performing a cricothyroidotomy or tracheotomy under local anesthesia is a lifesaving procedure in selected patients in the “cannot intubate, cannot ventilate” situation

• This approach has its drawbacks: it carries a 6% rate of complications such as hemorrhage or pneumothorax, in an elective scenario

• When a tracheotomy is carried out under local anesthesia, it is uncomfortable or even painful for the patient, who may already experiencing severe pain and anxiety

• Emergency surgical access is not frequently used, the surgical airway may be the route of choice when the maxillofacial trauma is extensive and the patient requires postoperative mechanical ventilation and MMF

• The Conventional Direct Laryngoscopy. Direct laryngoscopy using a conventional laryngoscope is a simple and straightforward method for securing the airway of a patient

• However, the risk of losing the airway is high, and hemodynamic side effects sometimes occur

PREPARING THE PATIENT FORMAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY

• Maxillofacial surgery is done after stabilization of the patient, the radiographic tests were performed, and all the injuries were identified.

• Operating on patients with a maxillofacial trauma and especially those with a severe complex comminuted panfacial fractures is quiet challenging for the surgeon.

• The surgeon has to perform fracture reduction, repair soft tissue injuries, and restore the occlusion

• To achieve a proper pretraumatic figuration and function, the occlusion has to be maintained and checked at all times during the surgery.

• choice of an airway device that will be used during the operation is to be agreed upon by the surgeon who is familiar with the planned procedure, including possible intraoperative change of plan and potential postoperative complications.

• If the patient arrived at operating room with an oral endotracheal tube, and prolonged ventilation is expected, the oral tube is to be changed to open tracheostomy

• SUBMENTAL OROTRACHEAL INTUBATION FOR MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY.

• Submental orotracheal intubation was developed in order to avoid the need for tracheotomy and to permit unfettered access to the oral region and intubation is done in -

• patients with comminuted fracture of the midface or the nose, where nasal intubation is contraindicated,

• patients who require restoration of the occlusion, • patients whose condition permits extubation at the end of surgery.

• Complications from submental endotracheal intubation include bleeding, damage to the lingual nerve, and the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve, damage to the duct of the submandibular gland, damage to the sublingual gland, salivary fistulae, and skin infections

DAMAGE CONTROL RESUSCITATION(DCR)

MASSIVE TRANSFUSION

• MT is defined as the transfusion of ≥ 10 red blood cell (RBC) units within 24 h

• Other definitions are in use: transfusion of > 4 RBC units over 1 h with anticipation of continued need and replacement of > 50 % of the total blood volume (normal adult male near 70 ml/kg, female near 60 ml/kg) with blood products within 3 h

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

HYPOTENSIVE RESUSCITATION• Early and aggressive fluid administration to restore blood volume may

be associated with several adverse effects such as: • dislodgement of blood clots (by increasing hydrostatic pressure on the

wound) • dilution of coagulation factors and • hypothermia• Permissive hypotension represents a strategy through which blood

pressure is maintained at low values (ex. By restricting/avoiding fluid supplement) until hemorrhage is controlled, while accepting a limited period of suboptimal perfusion of end organs .

• Recent guidelines suggest the maintenance of different SBP values (for TBI and non-TBI patients)

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

HEMOSTATIC RESUSCITATION

• post-traumatic coagulopathy was considered to be the result of :-• loss of procoagulant factors (caused by consumption and

bleeding), • hemodilution (caused by fluid resuscitation) • coagulatory dysfunction (due to acidosis and hypothermia)• “Acute traumatic coagulopathy” is characterized by an up-

regulation of endothelial thrombomodulin, which forming complexes with thrombin, promotes anticoagulation as well as by endothelial dysfunction-induced hyperfibrinolysis

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• Adequate detection and treatment of post-traumatic coagulopathy mandates early and repeated monitoring of prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), fibrinogen levels and platelets count

• Utilization of recently introduced viscoelastic testing, such as thrombelastography, may be useful for better characterization of an existing coagulopathy and management of haemostatic therapy

• Major Trauma Transfusion (PROMMT) study shows that an early infusion of higher plasma and platelet ratios was associated with decrease mortality within 6 h of admission.

• In the first 6 h, patients with ratios lower than 1:2 were 3 to 4 times more likely to die than patients with ratios of 1:1 or higher.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

.

• A 1:1 ratio of plasma and platelets was associated with decreased early mortality compared with lower ratios

• The Pragmatic Randomized Optimal Platelet and Plasma Ratios (PROPPR) trial is a prospective randomized pragmatic study which compares a 1:1:1 ratio of plasma: platelets: RBCs with a 1:1:2 ratio in 680 severely injured patient

• Early administration of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 ratio compared with a 1:1:2 ratio did not result in significant differences in mortality at 24 h or at 30 days.

• However, more patients in the 1:1:1 group achieved hemostasis and fewer experienced death due to exsanguination at 24 h.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

DAMAGE CONTROL SURGERY• Initial management of these injuries involves: • Airway management• control of hemorrhage • prevention of disability from• central nervous system injuries.• Penetrating maxillofacial and neck injuries result in a complex of lacerations,

open fractures, profuse bleeding, tissue avulsions, eye injuries and burn• The critical immediate life-threat following maxillofacial injury results from

airway compromise due to oropharyngeal bleeding, swelling, and loss of mandibular structural integrity.

• Once the airway is secured, direct pressure and aggressive packing of open bleeding wounds will control all but the most catastrophic hemorrhages

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• Rationale dictates that direct manual pressure and aggressive packing of open bleeding wounds or bleeding nasal and oropharyngeal cavities should be implemented without further delay in order to minimize further blood loss.

• External fixation of unstable anterior mandibular fractures using available means (orthopedic pin fixators, wire ligatures etc.) may assist in preventing airway compromise, as well as reduce profuse bleeding, pain and morbidity often associated with such injuries

• More significant bleeding can be controlled by angiographic embolization or selective ligation of the external carotid artery while simultaneously protecting the brain, cervical spine, and the eyes from further injury.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• Head and neck injuries should be copiously irrigated, wound contaminants removed, clearly nonviable tissue fragments should be debrided and the wounds covered to prevent further contamination.

• Suturing of soft tissue lacerations covering underlying bone fractures should be deferred so that such fractures should not be overlooked during subsequent examination of the patient.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

NECK ANATOMY• It is useful to divide the anatomical structures of the neck into five

major functional groups, in order to facilitate and ensure a comprehensive assessment and surgical approach:

• Airway - pharynx, larynx, trachea, lung.• Major blood vessels - carotid artery, innominate artery, aortic arch,

jugular vein, subclavian vein• Gastrointestinal tract - pharynx, esophagus.• Nerves - spinal cord, brachial plexus, cranial nerves, peripheral

nerves.• Bones - mandibular angles, styloid processes, cervical spine Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• The platysma defines the border between the superficial and the deep structures of the neck.

• If a wound does not penetrate deep to the platysma, it is not classified as a significant penetrating neck wound.

• As transverse cervical veins running superficial to the platysma may bleed profusely when severed, they are easily controlled by direct pressure, and can be managed by a simple ligature.

• The sternocleidomastoid muscle divides the neck into the posterior triangle which contains the spine and muscles, and the anterior triangle which contains the vasculature, nerves, airway, esophagus and salivary glands

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• When evaluating penetrating neck injuries, the neck is divided into three anatomic zones for purposes of initial assessment and management planning:

– Zone I: extends between the clavicle/suprasternal notch and the cricoid cartilage (including the thoracic inlet). Surgical access to this zone may require thoracotomy or sternotomy. Major arteries and veins, trachea and nerves, esophagus, lower thyroid and parathyroid glands and thymus are located in this zone.

– Zone II: lies between horizontal lines drawn at the level of the cricoid cartilage and the angle of the mandible. It contains the internal and external carotid arteries, jugular veins, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, recurrent laryngeal nerves, spinal cord, trachea, upper thyroid and parathyroid glands.

– Zone III: extends between the angle of the mandible and base of skull. It contains the extracranial carotid and vertebral arteries, jugular veins, cranial nerves IX–XII and sympathetic nerve trunk. Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

INITIAL ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF NECK WOUNDS

• Casualties with apparent signs of significant neck injury, including active pulsatile hemorrhage, expanding hematoma, bruit, pulse deficit, subcutaneous emphysema, hoarseness, stridor, respiratory distress or hemiparesis, require urgent surgical consultation and immediate operative management

• first priority in penetrating neck trauma is to assess and secure the airway, keeping in mind the potential for concomitant cervical spine injury

• Orotracheal intubation is the initial method of choice for securing the airway under most circumstances. Nasal intubation and fiberoptic intubation techniques are technically more difficult to perform and require special equipment

• Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• Cricothyroidotomy is the preferred method for establishing an immediate airway in cases where rapid endotracheal intubation is not possible or contraindicated.

• Emergency tracheotomy is the preferred method of establishing a definitive airway in case of suspected tracheal disruption.

• In difficult intubation patients with large anterior penetrating neck wounds, urgent airway can be established by direct intubation of the trachea through the wound.

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

BLEEDING• Vascular injury is noted in 20 % of cases of penetrating neck

trauma, and exsanguinating hemorrhage is the primary cause of death in such cases

• Life threatening facial hemorrhage in maxillofacial surgery has an approximate incidence of 1 % in the trauma patient

• Conservative measures such as anterior and posterior nasal packing are recommended

• Zone II neck injuries with hard signs of vascular injury require immediate surgical exploration. Vascular injuries in zone II mandate a high index of suspicion towards tracheal and esophageal injuries.

• Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• Proximal (Zone I) carotid injuries require partial sternotomy for proximal control. Injuries to the common or internal carotid arteries may be repaired using lateral arteriography, patch angioplasty, end to end anastomosis or bypass

• If the patient is in extremis, the common or internal carotid vessels may be ligated.

• This approach leads to dismal outcomes, with stroke rates exceeding 20 % and mortality approaching 50 % .

• An alternative approach to ligation would be the placement of a temporary shunt between the two ends

• In case of distal internal carotid (Zone III) injury, ligation is appropriate if the distal end can be also ligated. In case the distal end is within the skull base, a size 3 Fogarty embolectomy catheter can be used to occlude the distal end allowing it to thrombose

• • Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• Embolization of the bleeding vessel was also recommended as the most reliable technique for the control of hemorrhage .

• External carotid artery injuries may be repaired using standard techniques or ligated.

• Transposition of external to internal carotid artery is particularly useful when the internal carotid artery cannot be repaired, as an alternative treatment method to ligation

• Hard signs mandating immediate exploration of the neck:• Uncontrollable hemorrhage• Rapidly expanding hematoma• Palpable thrill or audible bruit• Focal neurological compromise• Absent or decreased pulses in the neck or upper extremities

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

• Bleeding vessels in the neck should never be blindly clamped or probed.• Most survivable hemorrhage from neck wounds can be controlled with

direct pressure over the wound against the vertebral column, or by packing the wound with gauze.

• If violation of the platysma is uncertain, manual spreading of wound edges without probing and visual inspection of the platysma integrity is recommended.

• Intravenous access should be attained on contralateral side or in the lower torso/extremities.

• It is useful to triage patients with penetrating neck injuries as either symptomatic or asymptomatic

• Symptomatic injuries require immediate surgical exploration, while asymptomatic patients maybe observed pending completion of appropriate studies guided by the location of the wound and availability of resources

Krausz et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2015)

POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF THE PATIENTWITH MAXILLOFACIAL TRAUMA

• Following surgery, the mucous membranes are edematous, the soft tissues are swollen, and the airway may be compressed.

• Neck expandability is relatively low and even a small hemorrhage in the region could result in airway compromise.

• Peterson et al. found that 12% of complications arose at extubation and 5% during recovery

• It is important to prevent nausea and vomiting because of the risk of gastric content aspiration especially in those patients with MMF, because pulmonary aspiration is plausible. For those patients with a tracheotomy tube, the patient may be awakened and allowed to breathe spontaneously through the tracheostomy tube for a few days in order to ensure a safe recovery.

CONCLUSION• Airway management of patients with maxillofacial trauma is

challenging. • The clinical status and features of the trauma dictate the

approach for securing the airway, and a series of steps are to be planned before airway management is initiated

• Knowledge of the specific attributes of the difficult airway, expertise in the appropriate techniques for managing the difficult airway, familiarity with the various airway devices, and prompt recognition of a failed airway are necessary for optimal patient care

• Teamwork between the maxillofacial surgeon, the anesthesiologist, and the trauma expert, in which each specialist contributes his/her expert knowledge, is mandatory for better outcomes.

THREE CHANGES TO BLS 2015

• NOT BREATHING? NALOXENEThe administration of naloxone by trained BLS providers is reasonable in patients with abnormal breathing and suspected opioid ingestion

• OPIOID OVERDOSE EDUCATIONTraining to treat an opioid overdose can be provided to opioid abusers and their close contacts

• MANUAL SPINAL IMMOBILIZATIONIn suspected spinal cord injuries, lay rescuers should manually immobilize the spine with their hands rather than using immobilization devices

TOP FIVE CHANGES TO ACLS 2015

• In an effort to streamline and simplify cardiac arrest algorithms, vasopressin has been removed. Epinephrine and vasopressin has equivalent outcomes

• Ultrasound has been added as an additional method for confirming endotracheal tube placement

• Non - shockable rhythms (e.g PEA, pulseless electrical activity) may have distinct pathophysiologic origins. It is reasonable to administer epinephrine ASAP to these non shockable rhythms

• Use max. Fio2 during CPR , this recommendation was strengthened ,but remember to titrate your oxygen after ROSC(return of spontaneous circulation)

• Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation( ECMO) is a possible alternative to conventional CPR in patient with refractory cardiac arrest if the etiology is thought to be reversible

THANK YOU