Egyptian trEasurEs -...

-

Upload

truongtuyen -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

Transcript of Egyptian trEasurEs -...

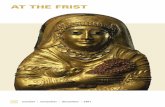

Egyptian trEasurEs from the Brooklyn Museum

October 7, 2011–January 8, 2012

Frist Center for the Visual arts e ingram gallery

t O L i V E F O r E V E r

to Live Forever: Egyptian treasures from the Brooklyn Museum

Civilization in Egypt began around 5300 BCE (before the common era), when nomadic people established

communities along the banks of the Nile River. Pharaonic

rule began around 3000 BCE and lasted until the end of

Roman control at 642 CE. Through these millennia, the

culture was unified by a belief in life after death. To Live

Forever: Egyptian Treasures from the Brooklyn Museum features

objects—sculptures, human and animal mummies, papyrus

documents, and tomb furnishings—that were meant to

help people reach the afterlife and remain there through

eternity. With works ranging from a simple yet delightfully

abstract female figurine, dated about 3650–3300 BCE

(fig. 1), to a mummy with a realistically painted face covering,

created soon after the time of Christ (cover), the exhibition

enables the contemporary audience to admire the aesthetic

achievements of the ancient Egyptians. At the same time, it

offers insight into the economics of attaining the afterlife by

comparing funerary objects made for royalty and the non-royal

elite to those produced by members of the lower classes.

While ancient Egyptian understanding of the afterlife was

complex, at its core was the denial of death’s finality. Magic

rituals and objects placed in tombs were meant to ensure a

smooth transition to the afterlife, also known as the netherworld

Fig.1

ended, Osiris weighed the deceased’s heart to gauge his or

her adherence to principles of justice known as ma’at. If

the heart was equal to a feather, the dead had lived with

integrity and was allowed to enter eternity, to live as he or

she had before dying.

The source of this belief was the story of the death

and rebirth of Osiris, who with his wife, Isis, had

ruled Egypt at the beginning of time. In a fratricidal

power play, Osiris’s jealous brother, Seth, invited

the king to a party only to trap him in a special box

made exactly in Osiris’s dimensions. Seth and his

co-conspirators sealed the box and threw it into the

Nile; Osiris drowned and Seth claimed the throne.

Isis retrieved Osiris’s body and magically revived him

long enough so that they could conceive a child. She

also built temples for him where he could receive food

offerings after death, establishing the role of the tomb

and the notion that those in the afterlife had the same

needs they had in this life.

Egyptian funerary objects reflect the story of Osiris.

Elaborately inscribed and painted coffins and wood

or stone sarcophagi, as exemplified by the Large Outer

Sarcophagus of the Royal Prince, Count of Thebes, Pa-seba-

khai-en-ipet (fig. 3), are like the box in which Seth trapped

Osiris. Housing the coffin and sarcophagus, the tomb is

the site at which the passage to the afterlife—which mirrors

Osiris’s own journey—begins. Like Osiris, the deceased

continued to live as they had before attaining immortality,

so the tomb also contained functional objects, including

weapons for men and cosmetic containers, mirrors, and

grooming accessories for women. Other objects in the tomb

were exclusively for the next world. These included shabties

(singular “shabty” a word meaning “ one who answers”),

or duat. The duat was believed to be an improved version of the familiar world, complete

with its own fields, desert, and Nile River. It was situated below the earth, where the sun—

represented by the sun god Re—fled to in the west at the end of the day to begin his twelve-

hour flight through the night. At the end of the twelfth hour, Re was reborn into the eastern

horizon. Egyptians believed that after dying, they could follow Re’s journey and ultimately

become one with Osiris, the god of the netherworld. The Amduat (fig. 2), an ancient funerary

text developed from The Book of the Dead, gives an illustrated, detailed description of the

course the sun takes during its sojourn. The text provides the magic spells and cryptic

knowledge that the deceased must know and recite in order to complete this journey safely.

Knowledge of these mysteries was not enough to gain eternal life, however; once the journey

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

course of seventy days. Then priests poured an expensive

combination of imported and domestic resins inside the

body to preserve it. These preservatives ensured that

the body was both waterproof and resisted damage

caused by microorganisms and insects. The body

was then wrapped in linen and placed in a coffin,

now ready for the funeral service. A less expensive

method substituted an abdominal injection of

cedar resin for the surgical process. This resin

liquefied the internal organs, which were drained

through the rectum. Dehydration with natron

followed, along with wrapping in linen. In the

cheapest method, an enema allowed embalmers

to remove the internal organs through the rectum.

The costs of mummification did not simply arise

from the process itself, but also in the external

appearance of the mummy. The materials used in

the human mummy in this exhibition, a fifty-nine

year-old Greek named Demetrios (fig. 5), indicate

the wealth he commanded in life. The pigment in

the red linen shroud contains lead imported from

Spain, while the face is covered by a sophisticated

portrait of the deceased, done in the medium of

encaustic, or wax plus pigment. The divine symbols

on the shroud and Demetrios’s name and age are in

gold leaf, a valuable commodity even in ancient times.

The range of costs associated with mummification

is similar to that of objects created for the tombs.

While royalty could afford the most rare and beautiful

materials available and could employ the finest

craftsmen, the literate elite, many of whom were clerks,

government officials, or priests, commissioned works

composed of less expensive materials, made by artisans

mummiform figurines representing servants who would

work in the fields for the deceased in the afterlife. Tombs

were also the site in which the deceased’s survivors

would provide food and other necessities, as Isis had

done for Osiris. They could make offerings of actual

food, or through representations of food, drink,

clothing, and other items rendered on tomb

walls.

The primary function of the tomb was to

hold the deceased’s body, which had been

mummified to ensure the same eternal life

enjoyed by Osiris. The preservation of

the body was essential, because it was

constituted of a person’s physical and

spiritual selves, the latter including the ka,

a spiritual double, born at the same time

as the person; the ba, associated with the

powers or personality of the individual;

and the ren, which controlled the person’s

fate. To live forever, the body and these

spiritual forces had to be preserved and

integrated into an akh, or effective spirit,

that existed as a tangible being in the

next world.

The Greek historian Herodotus, who

visited Egypt in the fifth century BCE,

described three mummification processes.

The most expensive involved the surgical

removal of the brain and major organs

(except the heart, needed for Osiris’s

judgment), which were stored in canopic jars

(fig. 4). Embalmers used natron, a naturally

occurring salt, to dehydrate the body over the

Fig. 5Fig. 4

At least four strategies were

available to those planning to

furnish a tomb on a budget:

they could substitute, imitate,

combine, or reuse. Substitution

involved choosing a cheaper

material instead of a precious

one. For example, faience, made

mostly from sand, was often

used in place of gold. Imitation

meant decorating one material

as if it were something more

expensive. Thus, a terracotta

mummy mask could be

painted yellow to imitate

gold. Combining was

a common strategy,

especially in coffin

sets. With expensive

coffins, there was

both a separate lid

and a mummy board,

which was shaped into a

life-size figure of the deceased

dressed in everyday clothing and placed

directly on the mummy. To save money, the typical mummy board decoration could be used

on the lid itself, thus combining the two. Reuse involved removing the name of a previous

owner and reinscribing an object for a new user. Coffins, statues, and shabties could all

be reused.

These methods of economizing reveal tremendous creativity among those who did not

have the means to furnish a tomb according to elite standards. While the craftsmanship

and extravagant materials used for the wealthy inspire admiration for their extraordinary

beauty, the objects made for the average person have a humble presence that is eloquent

in its own right.

who were not as prestigious as those

employed by the royalty. For this

group, furnishing a tomb was likely

the biggest expense they would

ever encounter. The lower classes

often produced their own funerary

objects and were frequently buried

with no coffin, sarcophagus, or

tomb for protection.

This exhibition provides

opportunities to compare

funerary objects made

for people with different

levels of wealth. An

example of this is seen

in the juxtaposition of a

professionally crafted,

gilded, and inlaid

mummy cartonnage

(fig. 6), representing

a woman whose life

was spent in luxury,

and a hand-modeled

and naively painted

terracotta mask (fig. 7), which was perhaps

fashioned by the deceased

herself, when she was still

alive, or a family member.

Though both covers adequately

protected the mummy, the materials

used demonstrate how poorer members of

society could also inexpensively provide the objects necessary to reach the

next world.

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Images:

Cover: Mummy Mask of a Man. From Egypt. Roman Period, early 1st century CE. Gilded and painted stucco, 20 1/4 x 13 x 7 7/8 in. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 72.57

inside front and back covers: Panel from the Coffin of a Woman (detail), From Asyut, Egypt. Middle Kingdom, late Dynasty 11 to early Dynasty 12, ca. 2008–1875 BCE. Wood and pigment, 17 1/2 x 71 1/2 x 1 1/4 in. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 1995.112

Fig. 1. Female Figurine. From Burial no. 2, el-Ma’mariya, Egypt. Predynastic Period, Naqada II Period, ca. 3650−3300 BCE. Painted terracotta, 13 3/8 x 5 x 2 1/2 in. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 07.447.502

Fig. 2. Papyrus of the “Amduat,” What Is in the Netherworld, of Ankhefenmut. From Thebes, Egypt. Third Intermediate Period, Dynasty 22, 945−712 BCE. Ink on papyrus, 8 7/8 x 11 13/16 in. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 37.1826Eb

Fig. 3. Large Outer Sarcophagus of the Royal Prince, Count of Thebes, Pa-seba-khai-en-ipet. From Thebes, near Deir el-Bahri, Egypt. Third Intermediate Period, Dynasty 21, ca. 1075−945 BCE. Gessoed and painted wood, 37 x 30 1/4 x 83 3/8 in. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 08.480.1a–b

Fig. 4. Canopic Jar and Lid (Depicting a Jackal). From Egypt. Late Period, Dynasty 26 (or later), 664−525 BCE or later. Limestone, 11 9/16 in. high x 5 1/4 in. diameter. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 37.894Ea−b

Fig. 5. Mummy and Portrait of Demetrios. From Hawara, Egypt. Roman Period, 95–100 CE Painted cloth, gold, human remains, and encaustic on wood panel, a: 13 3/8 x 15 3/8 x 74 13/16 in.; b (portrait): 14 11/16 x 8 1/16 x 1/16 in. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 11.600a−b

Fig. 6. Mummy Cartonnage of a Woman. From Hawara, Egypt. Roman Period, 1st century CE. Linen, gilded gesso, glass, and faience, 22 11/16 x 14 5/8 x 7 1/2 in. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 69.35

Fig. 7. Head and Chest from a Sarcophagus. From Egypt. Roman Period, 4th century CE. Painted terracotta, 17 1/2 x 17 1/2 x 4 1/2 in. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 83.29

inside back cover: Deir el-Medina Worker Grave in Shape of Pyramid, 2008. © Courtesy of Jim Womack

To Live Forever: Egyptian Treasures from the Brooklyn Museum has been organized by the Brooklyn Museum.

919 Broadway, Nashville, Tennessee 37203www.fristcenter.org

The Frist Center for the Visual Arts is supported in part by:

Platinum Sponsor: Silver Sponsor: Gold Sponsor: Barbara and Jack

Bovender

Hospitality Sponsor:

For more information on Egyptian Treasures fron the Brooklyn Museum at the Frist, scan the code.