ED 368 202 FL 021 987 AUTHOR Minami, Masahiko TITLE NOTE

Transcript of ED 368 202 FL 021 987 AUTHOR Minami, Masahiko TITLE NOTE

DOCUMENT RESUME

ED 368 202 FL 021 987

AUTHOR Minami, Masahiko

TITLE Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges:Cross-Cultural Comparison of Parental Narrative

Elicitation.

PUB DATE 8 Jan 94NOTE 36p.; Paper presented at the Annual Boston University

Conference on Language Development (18th, Boston, MA,January 8, 1994).

PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143)Speeches/Conference Papers (150)

EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage.DESCRIPTORS Cross Cultural Studies; Cultural Awareness; Cultural

Differences; *Cultural Influences; Foreign Countries;Language Patterns; Language Usage; *Mothers; *Parent

Child Relationship; *Parent Role; *Speech Habits;*Young Children

IDENTIFIERS Canada; Japan; United States

ABSTRACTConversations between mothers and children from three

different cultural groups were analyzed to determine culturallypreferred narrative elicitation patterns. The three groups included

Japanese-speaking mother-child pairs living in Japan,Japanese-speaking, mother-child pairs living in the United States,and English-speaking Canadian mother-child pairs. Comparisons of

mothers from these groups found that: (1) both Japanese-speakinggroups provided less evaluation of their children's discourse than

the English-speaking group; (2) both Japanese-speaking groups gavemore verbal acknowledgement than did the English-speaking group; and

(3) Japanese mothers in the United States requested more descriptionfrom their children than Japanese mothers living in Japan. At 5 years

of age, Japanese-speaking children, whether living in the United

States or Japan, produced about 1.2 utterances per turn, whereasEnglish-speaking children p,:oduced about 2.1 utterances per turn.Thus, whereas English-speaking mothers allow their children to takelong monological turns, and even encourage this behavior, Japanesemothers simultaneously pay considerable attention to their children's

narratives and facilitate frequent exchanges. Implications of thesefindings are further considered in the light of improvingcross-cultural understanding. (MDM)

***********************************************************************

Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be madefrom the original document.

***********************************************************************

"PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THISMATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY

\<<=3

TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCESINFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)

0

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges1

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges:

Cross-cultural Comparison of Parental Narrative Elicitation

Masahiko Minami

Harvard Graduate School of Education

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONOffice of Educafional Research and improvementEDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION

CENTER (ERIC)

OtarsScument has been reprOduCed asreceived from the person or organizationoriginating d

C Minor changes have been made to improverelaroducfion quatay

Potnts of view or oramons stateo v thm docu-ment do not necessarily represent officmtOE RI pusdron or policy

Running Head:

LONG CONVERSATIONAL TURNS OR FREQUENT TURN EXCHANGES

Author's Address: Harvard Graduate School of Education

Larsen Hall

Appian Way

Cambridge, MA 02138

* An earlier version of this paper was presented by the author at the Boston University

Conference on Language Development, January 8, 1994. The research described in this

paper was made possible through an American Psychological Association's Dissertation

Research Award and through a travel and research grant from the Harvard University

Office of International Education/Harvard Institute for International Development. The

author would also like to thank Carole Peterson, Memorial University of Newfoundland,

for providing the data that were collected as part of a research project supported by

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada grant 0GP0000513.

2 BEST COPY AVAILABLE

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges

Abstract

Children from different cultures develop differently according to the models that the

adults around them endorse. In divergent cultural settings, we can observe dissimilarities

in parental expectations and their resultant differing communicative styles (Heath, 1983).

Conversations between mothers and children from three different groups are being

analyzed to determine culturally preferred narrative elicitation patterns: (1) Japanese-

speaking mother-child pairs living in Japan, (2) Japanese-speaking mother-child pairs

living in the United States, and (3) English-speaking Canadian mother-child pairs.

Comparisons of mothers from these three groups yield the following salient contrasts: (1)

In comparison to English-speaking mothers, mothers of both Japanese groups give

proportionately less evaluation. (2) Both in terms of frequency and proportion, mothers

of both Japanese groups give more verbal acknowledgment than do English-speaking

mothers. (3) However, Japanese mothers in the U.S. request proportionately more

description from their children than do Japanese mothers in Japan. In addition, at five

years, Japanese-speaking children, whether living in Japan or the U.S., produce roughly

1.2 utterances per turn on average, whereas English-speaking children produce about 2.1

utterances per turn, a significant difference. Thus, whereas English-speaking mothers

allow their children to take long monologic turns, and even encourage this by asking their

children many descriptive questions, Japanese mothers simultaneously pay considerable

attention to their children's narratives and facilitate frequent turn exchanges. This

comparison demonstrates how, as primary agents of their culture, Japanese mothers,

while slightly influenced by Western culture, induct their children into a communicative

style that is reflective of their native culture. Implications of these findings are further

considered in the light of improving cross-cultural understanding.

3

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges3

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges:

Cross-cultural Comparison of Parental Narrative Elicitation

Children from different cultures develop differently according to the models that

the adults around them endorse. In divergent cultural settings, we can observe

dissimilarities in parental expectations and their resultant differing communicative styles

(Heath, 1983). Parent-child narrative discourse interactions provide good examples of

such cross-cultural differences. Conversation between parents, particularly mothers, and

their young children forms the context in which narrative discourse abilities emerge

(Snow & Goldfield, 1981) and vary across cultures (Schieffelin & Ochs, 1986). Through

conversational interactions, parents transmit culture-specific representational forms and

rules to their children (Bruner, 1990; Vygotsky, 1978).

While cross-cultural comparisons of narrative have already been made, most of

this research addresses cultural differences in the United States. Furthermore, data from

languages other than English are limited; we know next to nothing about how narrative

styles are acquired in other countries and other languages. Thus, to address this lack of

data, I have explored how Japanese mothers guide their children in the acquisition of

culture-specific styles of narrative discourse.

Purpose of the Present Study

The general purpose of the present study is to describe several aspects of Japanese

narrative, as it is used by mothers and their young children. Japanese mothers guide their

children in the acquisition of a narrative discourse style in culturally specific ways.

Examining Japanese mothers' narrative elicitation style thus offers important insights into

the cultural basis for language/discourse acquisition.

In light of this paradigm, furthermore, comparing Japanese mothers and English-

speaking mothers is interesting in many respects. I do this by introducing contrastive

narrative discourse analysis. Using the coding scheme that I will explain later, I compare

4

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges4

the parental styles of narrative elicitation of the two languages, English and Japanese. In

other words, I believe that contrastive narrative discourse analysis clearly identifies

discourse style differences between Japanese mother-child pairs and English-speaking

mother-child pairs.

Age Considerations

For the purpose of this study, young preschool children aged five were selected.

The reason that I focused on five-year-olds is due to age constraints that emerge from

analysis of the development of children's narratives. Children begin telling personal

narratives from the age of two (Sachs, 1979), but in any culture these early productions

are quite short through the age of three and a half years (McCabe & Peterson, 1991).

Three-year-olds' narratives are often simple two-event narratives; four-year-olds'

narratives are much more diverse, and five-year-olds tell lengthy, well-sequenced stories

that end a little prematurely at the climax (McCabe & Peterson, 1990; Peterson &

McCabe, 1983). In other words, preschool age represents the period of extremely rapid

development in the child's acquisition of narrative.

Methods

Sub'ects

Conversations between mothers and children from three different groups were

analyzed to study culturally preferred narrative patterns: (1) 10 five-year-old middle-

class Japanese children (5 boys and 5 girls, M= 53 years) and their mothers living in

Japan (none of these mother-child pairs had expetienced living overseas at the time of

interview); (2) 8 five-year-old middle-class Japanese children (4 boys and 4 girls; M= 5;3

years) and their mothers living in the United States; and (3) 8 five-year-old English-

speaking middle-class Canadian children (4 boys and 4 girls, M= 53 years) and their

mothers. Mothers were asked to tape-record at home conversations with their children

5

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges5

about past experiences. That is, following the method McCabe and Peterson (1990) used

in their studies, mothers were expected to ask their children to relate "stories about

perscnal experiences that have happened in the past" (p. 5). While talk about past

experiences was woven in with talk about the present and other non-narrative talk, I

focused on talk about past experiences. Further, some mother-child pairs talked about

more events than others. To establish a comparable data base, however, I decided to

analyze only the initial three narrative productions by each mother-child pair.

Use of "huun" as a global linguistic/discursive device in Japanese

When we closely examine Japanese mother-child interactions, we find that as one

of the global linguistic/discursive devices, many Japanese mothers use huun ("well").

Extending a topic narrative discourse requires interest on the part of both partners. When

a child talks about a particular incident, if the mother says, "huun, sorekara" (Well, then)

or more extensively "huun, sorekara do si-ta noT' (Well, and then what did you do?) the

mother's use of "well" indicates that she wants the child to extend the topic. If the mother

says to the child "huun" (Well), and the child then continues his or her story, on the other

hand, it can be interpreted that the mother simply acknowledges what the child has said.

Furthermore, if the mother says, "huun, hoka ni nani si-ta no kyo yotien de?" (Well, what

else did you do in preschool today?) the use of huun more likely signals that the mother

wants to switch topics.

In Japanese adult discourse, huun has been noted as serving a prefacing function

(Maynard, 1989; Yamada, 1992). The Japanese mother-child interaction, however,

reveals that the use of huun has a more complicated function than has originally been

discussed.

Example 1 below is from Ayaka, a 5-year, 3-month-old Japanese girl living in

Japan, and her mother's interaction. This example illustrates that the mother uses "huun"

in two ways. Ayaka and her mother are talking about what happened at a Buddhist

service for her late grandfather. The first huun comes right before the mother's topic

6

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges6

extension statement. Ayaka's mother pushes her to elaborate on the same topic further.

The second huun, on the other hand, comes right before the topic-switch; this time,

Ayaka's mother changes the topic of her narrative tellings.

Example 1 Ayaka and her mother's interaction

CHI: otya gasi mitai nayatu tabe-ta.

MOT: honto.

huun. [topic-extension]

sorekara?

CHI: u:n.

MOT: banana mo tabe-ta n?

CHI: un.

MOT: ne.

CHI: un tabe-ta.

MOT: oisik a-tta?

CHI: un.

MOT: huun. [topic-switch]

kyo wa nani s i te asob(n) de-ta n?

Translation

CHI: (I) ate something like a tea cake.

MOT: Really.

Well. [topic-extension]

Then?

CHI: Urn.

MOT: Did (you) eat a banana, too?

CHI: Yeah.

7

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges7

MOT: You see.

CHI: Yeah, (I) did eat (it).

MOT: Did (it) taste good?

CHI: Yeah.

MOT: Well. [topic-switch]

Today, what were (you) playing?

Example 2 includes a different use of huun. This example is from Tem, a 5-year,

I-month-old Japanese boy and his mother living in the United States. Teru's mother uses

huun not only as the "topic-switch" function but also as simple acknowledgment.

Example 2 Tem and her mother's interaction

CI-H: boku wa ne

zu:to ne

block atarasi i block de ne

zu:to hikoki ne

ano ne

hikoki toka kuruma toka ne

tukur te asob(n) de-ta.

MGT: huun. [simple acknowledgment]

CI-II: ano zu:to otonasiku asob(n) de ru no boku wa.

MOT: honto?

CHI: Yuri tyan to Aki kun to boku.,MOT: huun. [topic-switch]

obento kino wa takusan nokosi te ki-ta kedo.

kyo wa kirei ni tabe-ta ne.

CHI: un.

MOT: o:ku na ka-tta no?

CHI: un.

8

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges8

Translation

CHI: I was, you know,

always, you know,

using blocks, new blocks, you know,

always making an airplane, you know,

an airplane and a car, you know

playing with making (them).

MOT: Well. [simple acknowledgment]

CHI: Urn, I am always playing quietly.

MOT: Really?

CHI: Yuri and Aki and I.

MCT: Well. [topic-switch]

Speaking of the lunch yesterday, (you) left a lot.

But today (you) ate everything, you know.

CHI: Yeah.

MOT: Wasn't it too much?

CHI: No.

Thus, there are three different uses of huun: (1) prefacing of active topic-

extension, (2) simple verbal acknowledgment, and (3) prefacing of topic-switch.

Contrastive Narrative Discourse Analysis

To support generalization about the culture-specific nature of caregivers'

practices, I now turn to the comparison of the results of Japanese samples with the results

of a similar study of North American parent-child interactions (McCabe & Peterson,

1991; Peterson & McCabe, 1992).

In Example 3 below, Yuka, a 5-year, 6-month-old Japanese girl living in Japan,

talks about her experience when she participated in overnight schooling in preschool

(which is a common practice in Japanese preschools to socialize children as members of a

9

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges9

certain group). Example 4, in contrast, shows a dialogue between a 5-year, 6-month-old

Canadian boy, Paul and his mother. These two examples illustrate distinctive features.

Example 3

MOT:

CHI:

CI-II:

Yuka and her mother's interaction

campfire tte don na no?

(MOT: un)

ano ne

ma:ru k u ne

CHI: suwar te ne.

(MOT: LIL)1

(MOT:

CI-H: ano ne

CHI: ano ne

(MOT:

(MOT:

20

pa)

CI-11:

CHI:

"mo:er o yo" ne

(MOT: un\

no ne

uta toka ne

CHI: "ooki na uta da yo" toka ne

CHI: "i:tu made mo tae ru koto na ku:" no ne

CHI: o#uta toka.

Mar: uta (t)ta no?

CI-H: un.

.1 0

(MOT: EE)

(MOT: up)

(MOT: I.Lq)

Translation

MOT: What is the campfire like?

CHI: Um, you know,

CHI: in a circle, you know,

CHI:

CHI:

CHI:

CHI:

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges10

(we) sat, you know,

Urn, you know,

um, you know,

"burn," you know,

(MOT: uh huh)

(MOT: uh huh)

(MOT: uh huh)

(MOT: uh hun)

(MOT: uh huh)

(MOT: uh huh)

that, you know,

song, you know,

(MOT: uh huh)

CHI: "(This) is a big song," you know

"Forever, without an end," you know,

CHI: those songs

MOT: (You) sang?

CHI: Yeah.

11

(MOT: uh huh)

(MOT: uh huh)

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges11

Example 4 Paul and his mothes interaction

MOT: Paul, could you tell me about your trip to the dentist last night?

CHI: Okay.

MOT: And what happened there?

CI-H: All right, sure.

I'll tell you what happened at the dentist

I got a new toothbrush,

when it was finished.

And I had my teeth counted.

And I was and and was very happy to know that I had, ah, the teeth on the

on the bottom.

so I really liked, I really liked the ah dentist trip.

The comparison of these two examples shows Japanese children's utterances over

turns are much shorter than those of English-speaking children. Yuka's utterances are

produced in smaller units than traditional grammatical units, such as a sentence or a

clause. Segmented by sentence- or clause-final particles as well as intrasentential ones

(such as ma:ru k u ne (in a circle, you know) and uta toka ne (song, you know)), these

smaller parts serves as units in Japanese discourse. In other words, Japanese children

constantly use ne at the boundary of a discourse unit, such as a sentence or a phrase

boundary.

Moreover, by uttering ne, the speaker--the child in this case--often waits for the

hearer's brief vocalization of acknowledgment like un ("uh huh"). As Example 3

illustrates, the mother uses back-channels to construct mutually shared frameworks. In

other words, the hearer's back-channels effectively signal that she--the mother in this

caseshares the ground on which the speaker--the child in this case--is standing

(Maynard, 1989). Overall, therefore, this example shows a narrator's uses of this

12

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges

Japanese attent.Jn-getting device ne ("you know") in conjunction with displays of

attention from listeners, un ("uh huh"). In other words, this example illustrates how co-

construction takes place; the Japanese mother in this example speaks few words and few

utterances per turn and, instead, often simply shows attention, which, in fact, serves to

divide her child's utterances into small units. Also, at the end of the conversation, Yuka's

mother continued the words that Yuka was to say, as if filling in the blanks ("You

sang?").

On the other hand, Paul expands upon a topic of conversation--what happened at

the dentist (actions) and how he felt (evaluations); he talks on and on and on. More

important, Paul's mother allows him to do so.

Audio-tapes were transcribed verbatim for coding in the format required for

analysis using the Child Language Data Exchange System (MacWhinney & Snow, 1985,

1990). Speech was broken into utterances, and transcripts of all parents' speech were

scored according to Dickinson's (1991) system, which was previously used to analyze

how speech acts are mapped onto dialogic narrative discourse in English (Dickinson,

1991; McCabe & Peterson, 1991). By using Dickinson's coding scheme as a basis for

their own analysis, Minami and McCabe (1991, 1993) have devised appropriate coding

rules that are also applicable cross-linguistically, particularly to Japanese data (Figure 1).

Insert Figure 1 about here.

The following are coding rules for parental speech; according to these coding

rules, transcripts of all parents' speech were scored. Parental speech patterns were

basically divided into three types: (I) topic-initiation (or topic-switch), (II) topic-

extension, and (III) other conversational strategies, namely, statements showing attention.

Detailed guidelines for these categorizations are explained below:

13

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges13

(I) Topic-Initiation (Switching)

1. Open-ended questions initiating a new topic (e.g., "kvoo yotien de nani si-ta no?":

"What did you do in kindergarten today?").

2. Closed-ended questions initiating a new topic (e.g., "suuzi awase yar-ta?": "Did

you play matching numbers?").

3. Statements initiating a new topic (e.g., "kono mae Disneyland e i-tta de syo.":

"The other day we went to Disneyland.").

(II) Topic-Extension

4. Open-ended questions extending topics (e.g., "nani ga id ban suk i da-tta?":

"What did you like best?").

5. Closed-ended questions extending topics (e.g., "tanosi ka-tta?": "Did you enjoy

it?").

6. Statements extending a topic (e.g., "nani ka i tte-ta de syo.": "You were saying

something.").

7. Clarifying questions (e.g., "nani?": "what?").

8. Clarifying questions that were partial echoes (e.g., "dare ga tyu: si te kure-ta n?":

"Who gave you smacks?" after the child said, "tyu: tyu: tyu tte yar te.": "Smack,

smack, smacked me.").

9. Echoes (e.g., "sir a na ka-tta no.": "You didn't know" after the child said, "sir a na

ka-tta.": '1 didn't know.").

(III) Other Conversational Strategies

10. Statements showing attention, such as brief acknowledgment (e.g., "mi.": "Yeah.")

and prefacing utterances (e.g., "huun ": "Well.").

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges14

Speech patterns that are categorized into topic-extension are further categorized

into:

A. Descriptive statements (which describe a scene, a condition, or a state)

"ato Momotaro no hon mo ar-ta de syo.": "Besides there was a book about the

Peach Boy."

"denki ga tui te-ta ne.": "There were electric lights, you know."

"zibun de unten su ru kuruma?: "Is it a car that you drive on your own?"

B. Statements about actions (which, accompanied by an action verb, describe a

specific action)

"zyanken de saisyo kime-ta.": "We tossed first by scissors, paper, and rock."

"banana mo tabe-ta n.": "You also ate a banana."

"umi ni i tte-ta n?": "Did you go to the sea?"

'uki tyan ga ara-tta n.": "Yuki washed."

"nan te kai-ta no Yukari tyan wa typewriter de?": "what did you write with the

typewriter?"

C. Mother's evaluative comments

"sore ii ne.": "That's good, you know."

"Aki tyan tisa ka-tta mon ne.": "Because you were small, Aki, you know."

"uso.": "That's not true."

D. Mother's request for child's evaluative comments

"sore do: omo u?": "What do you think about it?"

"u tyan no doko ga kawai i no?": "What do you think makes the bunny cute?"

"oisi k a-tta n?": "Did it taste good?"

Once all the transcripts were coded, a series of Computerized Language Analysis

(CLAN) programs were employed to analyze them, such as frequencies of different

parental speech patterns and the ratio of utterances over turns.

15

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges15

Results

First, frequencies, which represent the impact that great talkativeness might have

on children's narration (e.g., McCabe & Peterson, 1991; Reese, Haden, & Fivush, 1992),

were analyzed. In addition, proportions were used because they correct for differences in

length and allows us to see differing relative emphasis on components of narration. To

test for the effect of group and gender, multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA)

were conducted for the major coding categories: maternal requests for the child's

descriptions, actions, and evaluations, maternal evaluations, statements showing

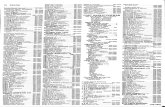

attention, and initiation (see Table 1).

Insert Table 1 about here.

With regard to frequencies, there was a multivariate effect of group, Wilks'

Lambda = .18, approximate F (12, 30) = 3.39, p < .01. Univariate ANOVAs were run for

each of the dependent variables. This effect was largely attributable to a significant

univariate effect on maternal statements showing attention, F (2, 20) = 4.29, p < .05, and

a marginal univariate effect on evaluations by mother herself, F (2, 20) = 2.98, p < .08.

The results were further analyzed in Bonferroni Post Hoc tests, which revealed that

mothers of both Japanese groups gave more verbal acknowledgment (i.e., statements

showing attention) than did English-speaking mothers (see Figure 2)

Insert Figure 2 about here.

In terms of proportions, there was a significant multivariate effect of group,

Wilks' lambda = .24, approximate F (10, 32) = 3.36, p < .01. Univariate ANOVAs were

run for each of the dependent variables. The effect of group was largely atcributable to

significant effects on maternal requests for descriptions, F (2, 20) = 3.82, p < .05,

i6

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges16

maternal evaluations, F (2, 20) = 9.13, 2 < .01, and statements showing attention, F (2,

20) = 6.32,2 < .01. The results were further analyzed in Bonferroni Post Hoc tests,

which revealed the following: (1) In comparison to English-speaking mothers, mothers

of both Japanese groups gave proportionately less evaluation (see Figure 3). (2) Mothers

of both Japanese groups gave proportionately more verbal acknowledgment (i.e.,

statements showing attention) than did English-speaking mothers (see Figure 4). (3)

However, Japanese mothers living in the United States requested proportionately more

description from their children than did Japanese mothers living in Japan. Moreover,

there was no statistically significant difference observed between Japanese mothers living

in the United States and English-speaking mothers (see Figure 5).

Insert Figure 3 about here.

Insert Figure 4 about here.

Insert Figure 5 about here.

Child's length of turns

Utterances over turns (UOT) can be defined as the number of utterances produced

by a speaker per turn. In addition to the frequencies of the coded behaviors, the "child's

utterances over turns" was examined. In order to resolve issues of equivalence between

the two languages (Japanese and English), the propositional unit was used for

transcribing the data. For example, arui te anti te ("(I) walked and walked") is simple

repetition/emphasis of one particular action and thus one proposition, while te de torte

ake-ta ("(I) grabbed (it) by hand and opened (it)") consists of two separate actions and is

17

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges17

thus considered two propositions. In other words, the definition of "utterance" in this

study is based on the information unit. By doing so, the same phenomena observed in

two different language groups were equated.

As Tables 2a, 2b, and 2c and Figure 6 illustrate, around the age of 5 years,

although males' utterances (2.33) are slightly longer than females' (1.90), English-

speaking children roughly produced 2.11 utterances per turn on the average. On the other

hand, Japanese children living in Japan and the United States produced 1.19 and 1.24

utterances, respectively. Thus, Japanese-speaking children, whether living in Japan or the

United States, produced about 1.22 utterances on the average.

A 3 x 2 (group x gender) analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the

variable, UOT (i.e. utterances over turns). This ANOVA yielded a significant main effect

of group, F (2, 20) = 7.76, < .01. The ANOVA results were further analyzed in

Bonferroni )st HOC tests, which revealed that Japanese children, whether living in Japan

or the United States, produced fewer utterances per turn than did English-speaking

children.

Insert Tables 2a, 2b, and 2c about here.

Insert Figure 6 about here.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that parental narrative elicitation styles reflect culture-

specific expectations about social interaction. While English-speaking mothers allow

their children to take long monologic turns, and even encourage this by asking their

children many descriptive questions, Japanese mothers, whether living in Japan or the

18

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges18

United States, simultaneously pay considerable attention to their children's narratives and

facilitate frequent turn exchanges.

It has been emphasized that parents in Western societies, particularly in North

America, encourage their child's independence and individual expression of choice. It

seems, then, that North American parents emphasize mastery of verbal skills in order to

emphasize these aspects. In contrast, the fewer evaluative comments of Japanese mothers

reflect Japanese socialization practices, which de-emphasize verbal praise in favor of a

more implicit valuation (Doi, 1971; Lebra, 1986). Whether living in Japan or the United

States, Japanese mothers use frequent brief vocalization of acknowledgment. From early

childhood on, therefore, children are accustomed to these culturally valued narrative

discourse skills through interactions with their mothers.

However, this study has also presented a more complicated picture than was

originally expected. Recall that Japanese mothers living in the United States requested

proportionately more description from their children than did Japanese mothers in Japan.

Also, recall that Japanese mothers use huun ("well") as a global linguistic/discursive

device. In reality, compared to Japanese mothers living in Japan, Japanese mothers in the

United States, right after uttering huun, were more likely to give their children descriptive

prompts, such as:

huun. ano sensei nan te name daro?: Well. What is that teacher's name? (Satoshi's

mother)

huun. nihon ni na i yatu ka no?: Well. Are they the things that we cannot find in Japan?

(Teru's mother)

It is certainly true that, after uttering huun ("well"), Japanese mothers living in the

United States provided their children with other prompts as well, such as maternal request

for evaluative comments and action statement. Thus, huun followed by a descriptive

1_9

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges19

prompt is not a sole factor contributing to the differentiation between the two groups of

Japanese mothers. However, it now seems clear that huun indicates a certain mental

transition; while uttering huun, the mother decides whether to continue the current topic

or terminate it and introduce a new one. It seems, therefore, that the more the mother

utters huun as prefacing of topic-extension, the further the child develops the topic.'

Japanese mothers, while slightly influenced by Western culture, induct their

children into a communicative style that is reflective of their native culture. This finding

is critical, particularly as educational settings in the United States become increasingly

multicultural and teachers often have difficulty understanding children from different

cultural backgrounds. I hope that this study will provide the basis to break through

cultural stereotypes and improve cross-cultural understanding.

1 A MANOVA with three dependent variables, (1) active topic-extension, (2) simple

verbal acknowledgment, and (3) topic-ending and then topic-switch, revealed a main

effect for group with Wilks' Lambda = .47, approximate F(3, 12) = 4.467, < .05.

Univariate ANOVAs, which were run for each of the dependent variables, revealed that

this effect was largely attributable to a significant univariate effect on active topic-

extension, F (1, 14) = 5.26, p < .05.

20

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges20

References

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dickinson, D. K. (1991). Teacher agenda and setting: Constraints on conversation in

preschools. In A. McCabe & C. Peterson (Eds.), Developing narrative stiucture.

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Doi, T. (1973). The anatomy of dependence (J. Bester, Trans). Tokyo: Kodansha

International. (Original work, Amae no kozo, published by Kobundo in 1971)

Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life and work in communities and

classrooms: New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lebra, T. S. (1976). Japanese patterns of behavior. Honolulu: University of Hawaii

Press.

MacWhinney, B., & Snow, C. E. (1985). The child language data exchange system.

Journal of Child Language, 12, 271-295.

MacWhinney, B., & Snow, C. E. (1990). The child language data exchange system: an

update. Journal of Child Language, 17, 457-472.

Maynard, S. K. (1989). Japanese conversation: self-contextualization through structure

and interactional management. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

McCabe, A., & Peterson, C. (1990). Parental styles of narrative elicitation. Paper

presented at the fifth International Congress of Child Language: Budapest,

Hungary.

McCabe, A., & Peterson, C. (1991). Getting the story: parental styles of narrative

elicitation and developing narrative skills. In A. McCabe & C. Peterson,

Developing narrative stricture. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Minami, M., & McCabe, A. (1991, October). Rice balls versus bear hunts: Japanese and

Caucasian family narrative patterns. Presented at the 16th Annual Boston

University Conference on Language Development, Boston, MA.

21

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges21

Minami, M., & McCabe, A. (1993, July). Social interaction and discourse style:

Culture-specific parental styles of interviewing and children's narrative structure.

Presented at the 4th International Pragmatics Conference, Kobe, Japan.

Peterson, C., & McCabe, A. (1983). Developmental psycholinguistics: Three ways of

looking at a child's narrative. NY: Plenum.

Peterson, C., & McCabe, A. (1992). Parental styles of narrative elicitation: effect on

children's narrative structure and content. First Language, 12, 299-321.

Reese, E., Haden C. A., & Fivush, R. (1992). Mother-child conversations about the past:

relationships of style and memory over time. Atlanta, GA: Emory Cognition

Project.

Sachs, J. (1979). Topic selection in parent-child discourse. Discourse Processes, 2, 145-

153.

Schieffelin, B. B., & Ochs, E. (Eds.) (1986). Language socialization across cultures.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Snow, C. E., & Goldfield, B. A. (1981). Building stories: The emergence of

information structures from conversation. In D. Tannen (Ed.), Analyzing

discourse: Text and talk (pp. 127-141). Washington, DC: Georgetown

University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological

processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Yamada, H. (1992). American and Japanese business discourse: a comparison of

interactional styles. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

22

Table 1.events

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges

....

Mean frequencies and percentages of mothers' prompts to children about past

JapaneseMothersin Japan

M

JapaneseMothersin U.S.

/A

English-speakingMothers

M

Fa values formain effectof GROUP

Requests fordescriptions

Frequencies 15.00 14.00 17.63 0.25Percentages 14.72% 20.81% 18.90% 3.82*

Requests foractions

Frequencies 23.50 15.50 17.88 0.95Percentages 24.30% 22.68% 19.84% 0.37

Requests forevaluations

Frequencies 16.50 8.75 21.38 2.04Percentages 17.18% 14.24% 21.44% 1.40

Evaluations bymother herself

Frequencies 15.40 7.75 28.25 2.98Percentages 14.69% 8.85% 28.01% 9.13**

Statementsshowingattention

Frequencies 27.10 17.50 7.50 4.29*Percentages 26.18% 28.31% 8.46% 6.32**

InitiationFrequencies 2.80 2.75 2.38 0.65Percentages 2.93% 5.11% 3.35% 2.71

*p < 0.05**R < 0.01

a Degrees of freedom = 2, 20

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges23

Table 2a. Child's Ratio of Utterances Over Turns: English-speaking Group

Child'sNameGenderCarl

Gary

Ned

Paul

English-sneakine Male English-speaking Female

UOT

3.857

1.929

1.550

1.968

Child'sName UOTGenderCam 1.581

Harriet 1.274

Kelly 1.619

Leah 3.136M 2.326 (1:2 1.038) M 1.903 (02 .837)

Table 2b. Child's Ratio of Utterances Over Turns: Japanese children in Japan

ChildNameGenderAkio

Taka

Takato

Tomo

Waka

Japanese Male Japanese FemaleChild's

UOT Name UOTGender

1.203 Ayaka 1.019

1.102 Mild 1.197

1.027 Minori 1.786

1.219 Sachi 1.157

1.078 Yuka 1.135M 1.126 (SD .083) M 1.259 (SD .302 )

Table 2e. Child's Ratio of Utterances Over Turns: Japanese children in U.S.

Boston Japanese Male Boston Japanese FemaleChild's Child'sName UOT Name UOTGender GenderKotaro 1.433 Aya 1.192

Satoshi 1.294 Mari 1.176

Shintaro 1.147 Nori 1.283

Tem 1.162 Yukari 1.258M 1.259 (02 .133) M 1.227 (SD_ .051)

24

Topic

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges25

Initiation (Switching)

Extension

Description Prompts

Action Prompts

Mother's EvaluativeComments

Mother's Request forChild's EvaluativeComments

Statements Showing Attention

26

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges26

Figure 2. Maternal Statements Showing Attention (Frequency)

70

60.

50-

20.

10

0

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges27

JAP SAT JUS SAT ENG SAT

Group

Japanese mothers English-speaking

in Japan in the U.S. mothers

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges/8

Fizure 3. Mother's Evaluative Comments (Percentage)

0 9

50

45

40

35

304,C

63' 25

20

15

10

5

0

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges29

JAP PMEV JUS PMEV ENG PMEV

GroupJapanese mothers English-speaking

in Japan in the U.S. mothers

3

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges30

Figure 4. Maternal Statements Showing Attention (Percentage)

31

60

50-

40.

Ct 30

k."

20

10

0

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges3 1

1

I

I

JAP PSAT JUS PSAT

Group

Japanese mothers

in Japan in the U.S.

32

ENG IPSAT

English-speaking

mothers

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges

Figure 5. Maternal Requests for Descriptions (Percentage)

33

30

27.5

25

22.5

20

17.5

15

12.5

10

7.5

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges33

JAP PDES JUS PDES

Group

Japanese mothers

in Japan in the U.S.

`4 4

ENG PDES

English-speaking

mothers

Long Conversational Turns or Frequent Turn Exchanges34

Figure 6. Child's Ratio of Utterances over Turns

35