EARLY EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT, 18(1), 93-110 I An ... · Phonemic Awareness Phonemic awareness is...

Transcript of EARLY EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT, 18(1), 93-110 I An ... · Phonemic Awareness Phonemic awareness is...

EARLY EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT, 18(1), 93-110Copyright @ 2007, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

I

An Experimental Valid~tionof a Preschool Emergent

Literacy Curriculufu

Barbara D, DeBaryshe and Dana M"GoreckiCenter on the Family IUniversityof Hawaii

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectivenessbf a preschool emergentliteracy enrichment curriculum. Participants were 126 Head Start children, theirteachers, and their parents. Matched centers were assigned to 1 of 3 conditions: ex-perimental literacy, experimental math, or control. Teachers in both experimentalgroups implemented either literacy or math instruction in s~all groups on a daily ba-sis, and parents and children completed supplementary learning activities at home.The control classroom implemented the ongoing Head Start curriculum. Children inthe literacy condition showedthe largest gains in phonemic awareness and emergentwriting skills; they also made greater gains on emergent reading than did children inthe math condition. There were no group differences on expressive vocabulary.Re-sults are discussed in terms of curriculumdesignand practical issues involvedin sup-porting preschools in the implementation of research-based instructional programs.

As an outgrowth of concern regarding the academic proJess of America's schoolchildren (e.g., No Child Left Behind Act of 2001; Snow, Bums, & Griffm, 1998),renewed attention has been paid to role of early childhood experiences in provid-ing a foundation for later literacy development (Bowm'an, Donovan, & Bums,2001; Neuman & Dickinson, 2001; V.S. Department of Education, 2005). A ro-bust body of evidence indicates that preschool- and kindergarten-age children withstrong oral language and emergent literacy skills show consistent advantages inreading, writing, spelling, and overall academic performance throughout theschool years (Barnhardt, 1991; Scarborough, 2001; Snowlet al., 1998; Vellutino &

Correspondence should be addressed to Barbara DeBaryshe, University of Hawaii Center on theFamily, 2515 Campus Road, Honolulu, HI 96822. E-mail: debarysh@hawaiLedu

94 DEBARYSHE AND GORECKI

I

Scanlon, 2001). Such findings underscore the need to promote developmentallysensitive emergent literacy instruction in all early childhood settings.

Current federal education initiatives (e.g., Reading First, Early Reading First)stress the importance of i~plementing literacy curricula that are firmly groundedin "scientifically based reading research" (U.S. Department of Education, 2005).

Although this is a worthyl aim, such policy mandates practices that are not yet wellsupported by applied research evidence. Although the basic research literature isgrowing, experts know relatively little about the extent to which results from suc-cessful, short-term interventions delivered by research staff generalize to literacy

instruction as delivered ~y preschool teachers in their classrooms.In an effort to address this gap, we conducted an experimental study of a scien-

tifically based reading research curriculum implemented by Head Start teachers.

The purpose of this stud1 was to evaluate a pilot version of Learning Connections(LC), an emergent literacy and mathematics enrichment curriculum for 3- to5-year-old children. In the pilot year, the literacy and mathematics portions of thecurriculum were implemented separately rather than as an integrated package.This article focuses on tHelanguage and literacy outcomes of the pilot testing year(see Sophian, 2004, for a detailed report on the mathematics curriculum and out-comes). It was hypothesized that children receiving the literacy curriculum would

show greater gains on mfasures ofliteracy development than would the children intwo different comparison conditions.

CJRRICULUM LEARNINGGOALS

There is widespread agreement that preschool and kindergarten children need to

acquire age-appropriat9 competence in the areas of oral language, phonemicawareness, alphabet knowledge, and print concepts (International Reading Associ-ation and the National Association for the Education of Young Children [IRA &NAEYC], 1998; Snow et al., 1998). Based on a review of the literature, we selected

these genera1learning d6mains, as well as the additional domain of emergent writ-ing, around which to build the curriculum (see Table 1). Each domain subsumedseveral more discrete learning goals. We included as learning goals only those skillareas for which there is ~trong correlational evidence linking skill attainment withlater academic achievement and/or experimental evidence that specific instructionin these skills leads to demonstrable gains in current performance or future literacy

ouwomes. I

Oral Language

The quality ofteacherJhild conversationaffectschildren's vocabularygrowth,es-pecially conversations that occur one-on-one or in small group settings (Beals,

EMERGENT LIJCY CURRICULUM 95

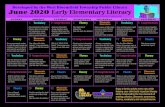

TABLE1Curriculum Domains and Specific Literacy Learning Goals

Oral language

Has increased vocabulary

Engages in conversations of increasing length and complexity

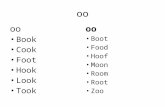

Phonological and phonemic awarenessIdentifies syllables within spoken words

Recognizes and generates rhymes

Recognizes and generates words that star( with the same sound

Alphabet knowledge and print conventions

Shows awareness of environmental print

Shows awareness of the usefulness of print

Identifies upper- and lowercase letters and knows letter-sound cOlspondence

Thacks printEmergent writing

Attempts to convey meaning via writing

Shows increasingly higher levels of emergent writing

DeTemple, & Dickinson, 1994; Dickinson & Sprague, 2~01; McCartney, 1984). Acontext that is especially well suited to supporting rich verbal interaction is

dialogic reading, in which children engage in active disc,",ssions of books as adultsread aloud. The adult scaffolds the discussion by using leading questions and re-

sponsive conversational extenders, gradually giving the cfildren more responsibil-

ity for lengthy and complex participation in the read-alo~d session. Dialogic read-ing has been used effectively by teachers and parents, resulting in significant andlasting gains in expressive vocabulary, grammar, and the semantic complexity ofchildren's speech (Hargrave & Senechal, 2000; Whitehurst et al., 1994;Whitehurst et al., 1988). Based on this evidence, dialogic reading and adult-childconversations during free play activities were selected ~s the two main instruc-tional strategies for promoting language development. ~

Phonemic Awareness

Phonemic awareness is the ability to hear and maniPulJte the individual sounds(phonemes) of which words are composed (Snow et k, 1998; Whitehurst &Lonigan, 2001). Phonemic awareness is one of the most robust predictors of con-current and future literacy skill (Adarns, Treiman, & Pressley, 1998; Juel, 1988;Nation & Hulme, 1997;Stanovich, Cunningham, & Feeman, 1984), and childrenwho enter school with high phonemic awareness usuallt learn to read and writewell, regardless of the literacy instruction method to lvhich they are exposed(Byme & Fielding-Barnsley,1995; Griffith,Klesius, & Kromrey, 1992).

Experimental investigations in which trained research assistants conductedphonemic awareness activities with small groups of preschool, kindergarten, or

I

96 DEBARYSHE AND GIORECKII

fIrst-gradechildren have shown increasedphonemic awarenessin just 4 to 12 ses-

sions (Bradley & Bryan~,1983; Byrne & Fielding-Bamsley, 1989, 1990, 1991;Cunningham, 1999).Th~1more intensive phonemic awareness interventions showlong-term effects (Bradley & Bryant, 1983; Byme & Fielding-Bamsley, 1991,1995). A small number of applied reports also indicate that phonemic awarenessprograms can be effectivelyimplementedby classroom teachers (Blachman,Ball,Balck, & Tangel, 1994;

jByrne & Fielding-Bamsley, 1995; Lundberg, Frost, &

Petersen, 1988);howeve gains are smaller than those foundwhen researchers im-plement similar curricul .

Many differentphonemic awarenessskills emergein a developmentalsequenceacross thepreschool to early elementaryschoolyears (Anthony,Lonigan,Driscoll,Phillips, & Burgess, 200

~

; Opitz, 2000). Based on this sequence, we decided to fo-cus on three skills appro riate for preschoolers: syllable boundaries, rhyming, andalliteration. We designed activities to promote both receptive (recognition) and ex-pressive (generation of novel examples) competence on the target skills. Examplesinclude clapping out syllables in familiar words, playing a picture concentration

game involving rhymin~ words, and going on an outdoor scavenger hunt to fInd

objects starting with a tlget sound.

Knowledge of the Alp~abet and Print Conventions

Phonemic awareness allows children to hear the sounds within spoken words, but

beyond this, children ne~d to know that these sounds can be represented by printed

letters and that sound-gfapheme correspondence is the key to generating and de-coding written language. Although knowledge of letter names is a strong predictoroflater reading performance (Scarborough, 2001), this skill in isolation is oflim-ited practical use unless it is part of a broader understanding of the more general al-

phabetic principle. Thusj the more successful literacy interventions provide a com-

bined focus on both pho1emic awareness and letter-sound correspondence (Ball &Blachman, 1991; Byrne & Fielding-Bamsley, 1991, 1995; Yeh, 2003). Knowledgeof the alphabet, in turn, is of limited use unless children also understand the mainfunctions and conventions of print. Foremost among these is the understanding

that print carries meanin~ that can be used for a variety of important purposes (IRA& NAEYC, 1998; Sn°"Y et aI., 1989). Presumably, this understanding of the bigpicture helps motivate children to persist in the difficult tasks of learning to readand write.

Intervention studies of print referencing during adult-child book reading (e.g.,

the adult tracking print rith his or her fmger as he or she reads aloud, discussingparts of the book such is the title, pointing to separate words on the page) haveshown that signifIcant gains in children's print concepts can be obtained in only 4to 8 weeks of shared r~ading sessions (Justice & Ezell, 2000, 2002). Somewhat

EMERGENT LITErCY CURRICULUM 97

longer interventions (i.e., 14-16 weeks) that combine nistruction in letter knowl-edge with phonological or phonemic awareness activ~tieshave shown markedgains on skills includingletter-sound correspondence,alphabet recognition, letternaming, letter writing, and novel word reading for both native English speakersand English-languagelearners (Roberts & Neal, 2004; Roberts, 2003; Yeh,2003).

There is some debate as to whether it is more useful to t,ach children letter namesor letter-sound correspondences (Treiman & Rodriguez, 1999). Both are impor-tant predictors of early elementary decoding skill (Loni~an,Burgess & Anthony,2000; Schatschneider,Fletcher,Francis,Carlson, & Footman, 2004); however,wedecided that knowledge of letter sounds would allow 4hildren to start using in-vented spellings more readily than would knowledgeof )etter names. For this rea-son, our alphabet instruction focused on letter-sound C

~

rrespondence rather thanon letter naming.

We designed activities to support the development of print tracking, letter-sound correspondence, and use of environmental print.

I

. These skills were taughtwithin the context of sharing messages and information that was meaningful andpersonally relevant to the children. Examples include jointly composing a morningmessage that was written by the teacher, who then asked ~child to track the print asshe reread the message to the group; exploring a mysteryioXfull of alliterative ob-

jects representing two to four fIrst sounds, which chil en sorted by group andmatched with the corresponding letter symbol; and prod cing a class book of signsIand other environmental print located in the school neighborhood.

I

Emergent Writing

Emergent writing is a fruitful area that has received vttle attention in the re-search-based reviews of recommended instructional practices (e.g., Snow et aI.,1988).Children's emergentwriting attempts follow a re~able developmentalpro-

gression (Sulzby,Barnhart, & Hieshima, 1989),and eme~gentwritinglevels corre-late concurrently and predictively with conventional I1[1easuresof spelling andreading processing (Barnhardt, 1991;McBride-Chang, 1998).One method for en-

couraging emergentwritingis to have childrenkeep a dail('journal. Althoughjour-nal writing has not been subject to experimentalscrutiny,jqualitativeevidencesug-gests that journaling is an enjoyable activity that increases understanding of printfunctions and helps childrenprogress to more advancedl6velsof emergent writing

(Baskt & Essa, 1990;Fang & Cox, 1999; IRA & N:::IC, 1998; Pontecorvo &Zucchermaglio, 1989). Our curriculum activities inch~(leddaily journaling, inwhich children were provided with prompts that encouraged them to integrate re-cently introduced alphabet and phonemic awareness skills into their journal en-

tries. Children also wrote their own books, both in class~d at home, which theyread to their teachers and peers.I

.u.. _l.

98 DEBARYSHE AND GORECKI

METHOD

Participants I

Participating children W

~e emolled in 11 year-ronnd, full-day Head Start class-

rooms located on the urb island of Oahu in that state of HawaiL Classrooms were

housed at nine different si es (seven sites had only one classroom, and two sites hadtwo classrooms) administered by the same Head Start program. Complete pre- andposttest data were availabte for 126 children. (Note that 26% of the original sample

was lost to attrition, alm~st all due to children leaving two of the control class-rooms before the end of the school year. There were no differences on age or anypretest score for those cWldren who completed the school year vs. those who leftHead Start.) Children's lean age at pretest was 47.10 months (range = 31-56months); 52% were boys The ethnic backgronnd of the sample was 43% Asian,37% NativeHawaiian, 1 % White, 5% not reported, 3% Hispanic, and 2% Black.According to Head Start~ecords,9% of the children were English-languagelearn-ers, and 6% had identifie

rspecial needs.

All lead teachers had a Child Development Associate credential, and 4 heldbachelor's degrees. Mos of the original teachers (88%) remained in their class-rooms throughout the corlrse of the study. Three teachers took maternity leave, and

1 aide left due to dissatisfGtion with her employment; all but one case of staff turn-

over occurred at the samr literacy site.

Measures I

Children were administo/ed a pretest battery consisting of three measures and aposttest battery consisting of four measures. The Expressive One-Word PictureVocabulary Test (Brow

!ll' 20(0) was used pre and post to measure expressive

vocabulary size. This te t shows high internal consistency (ex=.96) and test-re-test reliability (r = .85) for preschool children, as well as convergent validitywith other measures of vocabulary. Items involve showing the child a coloreddrawing and asking the child to name the picture. Target words include nonns,

collective nouns (e.g., c~~thing),adjectives, and verbs. Language quotient scores

(Le., age-adjusted deviapon scores based on a mean of 100 and standard devia-tion of 15) were used.The Test of Early Reading Abilities 3, Form A (TERA-3; Reid, Hresko &

Hammill, 2001) was ~srd pre and post to measure emergent reading skill. TheTERA-3 shows high ,ternal consistency and test-retest reliability with 3- to6-year-old children (et.=.91 and r =.98), and adequate convergent validity (rs =.52-.67) with other measures of reading skill has been demonstrated for early ele-I

mentaryschoolchildrel Unlikemanyotherinstrumentsthatassessreading,theTERA -3 includes conteltt relating to the use of environmental print, print concepts,

EMERGENTiCY CURRICULUM 99and print genres m addition to knowledge of the alphabet and basic word reading.Items include distinguishmg among food or beverage la*els, distinguishing lettersfrom numerals, indicating where on the page to start rddmg, and identifymg let-

ters. Although the 1ERA-3 does provide reading quotie~t scores, the mstrument is

normed for children aged 3.5 years and older. Roughly If% of our sample was too

young at pretest to be assigned a reading quotient score; ~pr this reason, we used to-tal raw scores (summed across the three 1ERA-3 subscales) and adjusted for age inth al . I I

eany~. IAt pretest, children were admffiistered a phonemic aWEeness battery based on a

prepublication version of the Preschool Comprehensivell est of Phonological Pro-cessing (Lonigan, personal communication). This measpre consisted of two sub-

scales of nine items each, m which children selected pair$ of pictures from an array

of four that showed either rhyming or alliterative words. tt posttest, two additionalsubscales were added, each including four items, m which children were asked togenerate a word that rhymed with or started with the sbe sound as a stimulus

word. The internal consistencies of the phonemic aware+ss measure (based on ei-ther two- or four-subscale scores) were et.= .69 at prete~t and et.= .74 at posttest.Raw scores were used, as no age-based norms are available.

Finally, an emergent writing sample was admffiistere~ at posttest only. After awarm-up item m which children were asked to write theif name, the children were

asked to write a list of "all the words or leners you know-\' This sample was scoredfor (a) the level of emergent writing based on Sulzby et al. (1989); (b) the numberof unique, recognizable upper- and lowercase letters; and\(c) the number of unique,recognizable words written using either conventional or ihvented spellmg. Each ofthe three scores was converted to z scores and summed to form a composite writingscore. As no pretest writing score was available to serve

1

1sa covariate, we used theraw score from the 1ERA-3 alphabet subscale; this subs, ale assesses lener identi-fication and lener-sound correspondence, which were the most closely related

skills for which a pretest measure was available. I

At the end of the school year, teachers, Head Start sfervisors, and parents mthe two LC conditions were admIDistered a short, anonYmous satisfaction survey.

The teacher/supervisor survey mcluded six open-en~ed items (e.g., "What

changes, if any, did you see m the children since you beg~ the LC program?") andan overall satisfaction item answered on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (verydissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). The parent survey m'cluded six closed-ended

items rangmg from I (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly atree) or I (poor) to 4 (ex-

cellent), and two open-ended items (e.g., "What did youflike best about LC?").

aIyzed for the older children using reading quotilnt scores. Results were almostidentical to those reported in Thbles 2 and 3 for raw scores in the full s~le.

I

100

DEBARYSHE AND rORECKIProcedures

Starting with a pool of 12 year-round, full-day sites, 9 sites were matched asclosely as possible for teather qualifications (both educationalcredentials and ob-I

served teaching qualitY),1rural versus urban locale, child ethnicity, number ofclassrooms, percentage O

fEnglish-language learners, and percentage of children

with special needs. Three sites were dropped because they were not a match with

any other site. Once satisfactorily matched trios were obtained, sites within eachtrio were randomly assigned to one of three conditions. Thus, our design was oneof blocked random assi~~ment. For the two sites with multipledassrooms, both

dassrooms were assigne~ to the same treatment condition. This resulted in four lit-eracy classrooms, four math dassrooms, and three control dassrooms.

The control condition ~mplemented the ongoing Head Start curriculum, which

was organized around th~ Head Start Performance Standards and allowed consid-

erable autonomy for each; classroom. Teachers were free to select dassroom teach-ing approaches and spe~fic activities, as long as the general content standardswere addressed. Teacher~ and parents in the literacy condition implemented a pilotversion of the LC literacy curriculum. Teachers and parents in the math conditionimplemented a pilot ver~ion of the LC math curriculum. The literacy and mathteachers received equal bounts of curriculum-specific support, induding twoinservice training worksHops, weekly lesson plans and specific learning activities,required teaching materiaIs, and weekly in-class supervision by a master's-levelmentor. Parents in the li

*acy and math conditions received instructions and mate-

rials for completing wee y home learning activities with their child. Teachers andparents in the control co dition received no special support. Thus, the math condi-

tion served as a strict antfntional control group for the literacy curriculum, and theregular Head Start cond~l:ionserved as a more traditional control. This design al-lowed us to tease apart the effects of the literacy and math curricula per se frompossible halo effects, or Igeneralized effects of increased supervision and profes-sional support. ,-

All children were acIbnistered the pre- and posnest banery by a trained re-search assistant in a qui6t area adjacent to the dassroom. Teachers in the literacy

and math conditions im~lemented the relevant portion of the LC curriculum fromOctober through April. f'\ll dassroom materials were provided, as were detailed

instructions for each c~culum activity. Teachers were given daily lesson plansthat included a morning circle activity and three small-group activities to be done

in small groups during ~ learning center rotation period. Each day, children in theliteracy pilot group participated in dialogic reading; journaling; and either an al-

phabet, print awareness,1 or phonemic awareness activity. Children in the math pi-

lot group participated if one cirde activity and one math activity per day. Thelearning activities wer:I,game-like, short in duration (5-10 min), and children'slearning was supported Iby teacher conversation and scaffolding of instructional

EMERGENT LITERACY CURRICULUM

I

101

supports. Activities were developmentally sequenced an~ lesson plans were devel-oped to move children through the activity sequence at ~ pace that was consistentwith each classroom's needs. Materials were available t6 the children for free ex-

ploration throughout the day. Teachers were also given fuggestions for transitionactivities and extension activities to be used across the sphool day.

To extend children's learning to the home setting, parents in the literacy andmath conditions were given a weekly home activity to

~

o with their child. The

home activities built on what children had recently been learning in class. Parentsin the literacy group were also encouraged to borrow oks from their child'sclassroom on a weekly basis. Most activities resulted in a product (e.g., a home-made book that parents placed in their child's classrooth portfolio). We used thenumber of returned home activities as an index of paren

~ParticipatiOn.Families

received support in implementing the home curriculum. e attended the ongoingmonthly parent meetings held in each Head Start classro m. At these meetings, wediscussed language and literacy developmentor math development,modeled up-I

coming home activities, and facilitated group diSCUSSi

I

n about parents' experi-ences observing and working with their children.

Teachers were also provided with extensive ongoin support. Two inserviceworkshops were provided, a 1.5-daytraining session in September and a half-dayrefresher training in January. A master's-level mentor !teacher visited each LC

classroom on a weekly basis to observe teachers using ~e curriculum and to pro-vide coaching and feedback. Finally, the mentor teach

q,

and lead researcher met

with each classroom every third week to model upco .ng classroom activities,discuss children's progress, answer teachers' questions, and suggest strategies toovercome any challenges.

RESULTS

Treatment Fidelity

Treatment fidelity in the liter~cycondition was modera

~

to good. Children in theliteracy group completed an average of 344.4 circle-tiro and small-group literacyactivities, or 72% of the activities indicated on the daily esson plans. (Both childabsences and teachers' not following the lesson plans co d contribute to this totalbeing less than 100%.) Even though two literacy clasJrooms were affected byteacher turnover, all but one site was informally jUdged

f

Y the mentor teacher asimplementing the curriculum with an acceptable to exce lent level of quality. Oneliteracy site had low rates of adherence to the daily le son plans, and the leadteacher at that site did not implement the activities in the desired manner. Parentsreturned an average of 40.1 % of the home activities; the operall return was loweredby minimal returns from the low-compliance site.

102 DEBARYSHEAND GORECKI

Gains in Children's La~guage and Uteracy SkillsThe analysis of children'slposttest literacy skills was conducted in two steps. First,each independent variablJ was analyzed using an omnibus analysis of covariance,I

in which condition (literacy vs. math vs. control) was the between-groups factor,

and child age and pretestlscore were the two covariates.2 Effect size estimates for

each covariate and the cpndition factor were computed using 1)2.The omnibusanalysis was conducted to assess the relative contributions of age, pretest, and cur-riculum condition to explaining variance in the dependent variable.

Because only two of ~e three pairwise comparisons were of interest, treatmenteffects were examined by computing planned comparisons (Keppel, 1982). Thefirst comparison contrasted the LC literacy condition with the LC math condition.

The second comparison ~ontrasted the LC literacy condition with the control con-

dition. Because the ori~nal hypotheses were directional, one-tailed tests wereused. In all cases, the de{>endentvariable was an adjusted posttest score, control-ling for child age and pretest. Effect sizes for the planned comparisons were com-puted in standard devia~on units using a weighted pooled variance based on theomnibus analysis of covclrlance (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001).

Results of the main ~alyses are shown in Tables 2 through 4. For each of the

four dependent variables(, pretest was a significant covariate, accounting for 10%to 56% of variance in P9sttest scores. The association between pre- and posttestwas strongest for expressive vocabulary and weakest for phonemic awareness. Agewas a significant covari~te for phonemic awareness and emergent writing, witholder children having hikher posttest scores. Age was not a significant covariatefor expressive vocabulmf, which was measured in an age-normed metric.

Contrary to our expectations, there were no group differences on expressive vo-cabulary. Results were Imore positive, but still mixed, for emergent reading.

Children in the literacy cfmdition had higher reading scores than did children in themath condition (M = 3.52, d= .34),but the literacygroupwasno different from thecontrol group on the emergent reading outcome.

In contrast, clear treftment effects were found for phonemic awareness andemergent writing. Children in the literacy condition had higher phonemic aware-ness scores than did chilaren in both the math (M = 3.10, d = .50) and control con-

I

2Given that children are n

tted inside classrooms, a multilevel analysis would be more appropriate

for this research design. How ver, with only 11 classrooms and three treatment conditions, we had too

few Level 2 units. One might. xpect that if teachers inlluence children above and beyond the curricu-

lum that those teachers emploY, an analysis of variance would tend to overestimate curriculum effects.

To confirm that the findings r1°rted here are not misleading, we conducted a multilevel analysis using

age and pretest scores as Leve~ 1 variables and dummy variables representing the three treatment condi-tions as Level 2 variables. To get the models to run, we had to estimate only fixed eft'ects, not allowing

the slopes of the Level 1predictors to vary across classrooms. Results from the hierarchical linear mod-

eling approach were very si[lar to the analysis of variance results reported here.

I

EMERGENT U~CY CURRICULUM

TABLE2 I

Means, Standard Deviations, and Adjusted lMeansfor Literacy Outcome Measures

103

Condition

Literacy (n = 51) Math (n =44) Control (n = 30)

Note. Adjusted means control for age and pretest score. Vocabjllary scores are language quo-

tients, reading and phonemic awareness scores are raw scores, and Friting scores are composite zscores.

ditions (M =3.73, d =.60). They also had higher scores on emergent writing (M =1.14, d =.47 for literacy vs. math; M = 0.76, d = .31 for iteracy vs. control).

Predicting Individual Differences in TreatmentOutc9me

Any intervention is unlikely to have uniform effects for ~l children. We were in-terested in identifying which children gained the most 40m LC. To this end, weconducted stepwise regression analyses to predict growth in literacy skills. Inde-I

L u-. H -

TMeasure M SD Adj.M M SD

Ad+MM SD Adj.M

Vocabulary 90.2 14.6 90.3 88.6 10.7 8.6 90.0 14.9 88.5

Emergent reading 18.6 10.6 18.0 14.0 7.6 1.4 17.0 9.0 17.4Phonemic awareness 13.2 7.0 13.1 10.5 5.6 1.0 8.5 6.4 9.4Emergent writing 0.7 2.7 0.6 -0.6 1.8 -9.6 -0.2 2.8 -0.2

TABLE 3

Analysis of Covariance Table

Dependent Variable FI p 112

Expressive vocabularyAge 0.06

I

.81 .00Pretest 150.99 .001 .56Condition 0.36 .70 .01

Emergent readingAge 3.51

I

.06 .03Pretest 83.39 .001 .41Condition 3.84 .02 .06

Phonemic awareness

Age 10.33 .002 .08Pretest 12.77

I

.001 .10Condition 5.74 .004 .09

Emergent writingAge 17.67

'

.001 .13Pretest 51.39 .001 .30Condition 5.12 .007 .08

104 DEBARYSHE AND GORECKII

Note. Means and standar~ errors are adjusted for pretest and age. Tests are one-tailed.

I

pendent measures were

l

age; the total number of LC activities each child hadcompleted in class; the total number of home activities returned; the relevantpretest score; and three Ilummy variables representing whether the child spokeEnglish as his or her flf~t language, had special needs, or was in his or her firstor second year of Hea

~

Start. We expected that, controlling for the other inde-pendent variables, postt st scores would increase as a function of treatment dos-age. However, this exp tation was not supported by the data in all but one case.Growth in phonemic awareness skills was higher for children whose parentscompleted more of the

E

lome literacy activities (P= .38,p = .006).For expres-sive vocabulary, emerge t reading, and emergent writing, the number of LC ac-tivities completed at ho e or at school was unrelated to child outcomes. Notethat there was limited range in the number of classroom activities completed, as

ill """'°" followed,° ,ame 1= pI...Consumer Satisfactio$

Surveys returned from ~8 LC literacy parents (a 75% return rate) indicated highlevels of satisfaction witf. the pilot literacy curriculum.There wereno differenceson any demographic or child pretest measures for literacy parents who returned asatisfaction surveyversus those who did not. All literacyparents (100%)agreedorstrongly agreed that thi

' child "learned a lot from the LC classroom activities."

We found that 90% of I teracy parents felt that their child "learned a lot from theLC family activities,"8 % agreedor strongly agreed that the home activitieswere"clear and easy to folloW,"and 92% said the family activities were "fun to do."When askedabout the

:E-erall program quality, 45% ofliteracy parents rated LC as

excellent, 50% as good, d 5% as fair. Literacy parents' open-ended comments in-dicated that their childr enjoyed the home activities and that working on them to-gether had increased thC(irunderstanding of their children's capabilities. Literacy

parents also appreciatei that the home activities provided "quality" one-on-one

time, in addition to incTasing their children's skills.

.L

TABLE 4Planned Contrasts

II

I Literacy V.f.Math Literacy vs. Control

Variable

tSE p d M SE P d

Expressive vocabulary 1.86 .36 .07 1.77 2.08 .20 .17

Emergent reading 3.52 1.33 .004 .34 0.53 1.48 .36 .05Phonemic awareness 3.0 1.13 .003 .50 3.73 1.28 .002 .60

Emergent writing 1. 4 0.36 .001 .47 0.76 0.41 .035 .31

EMERGENT~CY CURRICULUM 105

Teachers were less uniformly enthusiastic, although )"1 positive. In all, 25% of

LC literacy teachers and their supervisors said they w:; very satisfied with LC,67% were satisfied, and 8% felt neutral about the program. Supervisors' ratingswere more positive than those of the classroom teachers. ~ntheir open-ended com-ments, literacy teachers indicated that the children had n1ade good progress on thetarget LC skills, especially in the areas of writing and eniergent spelling. The pre-pared lesson plans and materials, inservice training, and in-class mentoring wereappreciated. Several literacy teachers felt that the curri

~

~ulum was too academic

andLorinterfered with their autonomy in deciding the c ntent of the school day.Some requested that a wider range of activities be provi ed for younger and lessskilled children. I

DISCUSSION

Results suggest that the LC emergent literacy CurriCul

~

was more effective than

were ongoing Head Start practices. Compared t, children exposed toteacher-developed curricula, children in LC classrooms showed greater gains inthe areas of phonemic awareness, emergent writing, and to a lesser extent, emer-gent reading. Effect sizes were generally moderate in ma

Eitude, ranging from .31

to .60 standard deviations. This pilot study confmns that ith adequate mentoringand support, Head Start teachers and parents can serve as hange agents by deliver-ing a research-based literacy eurichment curriculum with adequate fidelity.

LC had the most effect on children's phonemic awar

~lness and emergent writ-

ing. This was seen in both the magnitude of the effect si s and the in finding thatLC classrooms showed greater gains than did both comp .son groups. These twoareas of the curriculum are perhaps less familiar to teachers (Hawken, Johnston, &Donnell, 2005) and may have represented a new emPh

~

1is in classroom learningactivities. To the best of our knowledge, only 1 teacher ou side the LC literacy pilot

group made use of daily journal writing. Nor did teach s outside the LC literacy

pilot group expose children to activities that strengthen phonemic awareness be-yond the use of finger-plays, rhyming books, and songs. However, all classroomshad a daily read-aloud session that was similar to the LC

j

dialOgiCreading activitywith the major exception of group size (in most control classrooms, books wereread to the class a whole, not to small groups of children. This fact could explainthe lack of treatment effects for expressive vocabulary. It 1sless clear why the liter-acy group outperformed the math group, but not the contr~l condition, on emergentreading. All classrooms worked with children on alphabet recognition on a regularbasis (although LC literacy classrooms taught both letter ~ames and letter sounds),which may have contributed to more similar performanc~ on the emergent reading

test. It is also possible that teachers in the math conditiop reduced the amount of

time and attention devoted to this aspect of literacy to fOfuS on the LC math.

L.

106 DEBARYSHE AND GORECKI

In addition to being exJosed to more frequent and repeated experiences with writ-ing and phonemic awaredess, children in the LC literacy condition were providedwith literacy instruction ~at was mutually reinforcing. Phonemic awareness, letterrecognition, letter-soun

~

correspondence, and emergent writing are not skills thatdevelop independently. or example, there is evidence that teaching phonemicawareness in combinatio with letter recognition is more effective than focusing onphonemic awareness alone (Ball & Blachman, 1991; Treiman & Baron, 1983; Yeh,2003). And although alev

r

l of both phonemic awareness and letter knowledge is cer-tainly needed to use inven ed or phonetic spellings, attempting to write phonetically(thus invoking the alphab tic principle) also increases one's sensitivity to phonemesI

(Adams et al., 1998). Ina typicalLC classroom week, children would engagein all ofthe following experience

~

l: (a) be introduced to the grapheme rn,(b) learn its associ-ated phoneme fm!, (c) ha e several concrete experiences listening to and generatingwords containing that so d, (d) go on scavenger hunts at home to find objects withnames that include that sound, (e) be encouraged to try to write a recognizable ver-sion of the letter, and (f) be prompted to write a story in theirjournal about something

important to them that starts with the sound fm!. By addressing several literacy skills

simultaneously, it is pos~tb~e that children progressed further than they would havehad each skill been taught in isolation.

An important obstaclb to implementing the pilot curriculum was the lengthylearning curve on the Paritof the teaching staff. Almost half of the pilot period had

passed before new class~oom routines were established and teachers and childrencirculated through the LC activities smoothly and efficiently. Because this was anexperimental eValuatiO

~

Participating teachers did not volunteer to adopt the LCcurriculum, and, initiall there were divided opinions about the wisdom of the pro-gram. First, asking teach rs to work in small learning groups for portions of the dayrequired some classrooms to make changes in their schedules and strategies for shar-ing responsibilities within the classroom teaching team. For example, some class-rooms had minimal tim

1

in the schedule slated for learning centers or planned in-

sU:Ucti~n, and s~me lea teachers expected ~eir assistant teachers, to assume apnmanly custodial role In order for each chIld to have 20 to 30 nun per day of

small-group or individm~f attention, classroom staff had to spend more time actively

scaffolding children's l,~ng and less time monitoring larger groups. Second,teachers had to become IFliar with new concepts (such as the distinction betweenletter names, letter sounds, and phonemes; or understanding that different types ofverbal questions place 4ifferent levels of linguistic and cognitive demand on the

child) before they were 1ble to clearly see how the LC activities were linked to spe-

cific child learning goal~rThird, some teachers started with the belief that intentionalteaching activities couldrot bedeve10pmentallyappropriate.Thisconcemmirrors ahigh-profile debate tha, is currently engaging the early childhood community,namely, the relative m

E'ts of explicit versus embedded instruction (McGee &

Richgels, 2003; Yeh,2 03). Most LC activitiesused instruction that could be de-scribed as embedded wiJ . ongoing meaningful activities (e.g., dialogic reading,

-'--- J --. --- -- --

EMERGENTuTERAcy CURRICULUM 107

print tracking during morning message), whereas others +ere more distinct and fo-cused (e.g., table games in which children were asked to generate rhyming words).Nationally, Head Start teachers report using many indirec

1

' teaching strategies, suchas environmental design, or supplying arange of materials 0 encourage independentexploration to meet program literacy goals; in contrast, te chers report less frequentuse of strategies that involve direct teacher-child interac~on (Hawken et al., 2005).Finally, the teachers in our study were at many different places in their own profes-sional development and ranged widely in terms of fOrmal

~

1reparation in early child-hood education, years of classroom experience, knowle ge of child deve

.

lopment,and confidence in taking on a new challenge.

We did not design the evaluation process to closely track changes in teachers'knowledge, skills, and attitudes. However, our personal ~eflection on the processled us to make three general conclusions relevant to the srtccessful implementationof classroom- and home-based interventions. FirsJ achieving change inadult-child teaching interactions takes time. Second, ibplementing a complex

curriculum enrichment program such as LC probably reqIires a mentoring compo-

nent. And finally, teachers and parents do not automatica~~ embrace a new curric-ulum, especially if they have reservations about pedagogical techniques or theamount of time and effort the curriculum requires. Appr~iating a new curriculum,as well having confidence in one's ability to implement new techniques, is in largepart an outcome of trial- and-error experience, in which tclachers and parents cometo see for themselves how their new efforts result in greatdr gains than they had pre-viously come to expect from preschool children. I

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I

This research was supported by a Head Start-Univerdty Research Partnership

Award from the Department of Health and Human Se~ices, Administration forChildren and Families. We wish to express our deep appreciation to the children,parents, teachers, and staff of Oahu Head Start.We also iliankEmestine Enomoto,Cecily Omelles, Tracy Trevorrow,Lois Yamauchi, thetonymOUSreviewers, andthe journal editor for their comments on drafts of this' cle. Earlier versions ofthis paper were presented at meetings of the Society for esearch on Child Devel-opment and the Family Research Consortium. I

REFERENCES

Adams, M. J., Treiman, R., & Pressley, M. (1998). Reading, writing, aJ literacy. 1nl. E. Sigel & K. A.

Renninger (Eds.), Handbook of child p.rychology: Vol. 4. Child P.ryChOIOgyin practice (5th ed., pp.

275-356).NewYork:Wiley. I

108DEBARYSHE AND PORECKI

Anthony, J. L., Lonigan, C. J., 4SCOll, K., Phillips, B. M., & Burgess, S. R. (2003). Phonological sen-sitivity: A quasi-parallel progression of word units and cognitive operations. Reading Re.fearchQuarterly,38,470-486. I

Ball, E. W., & Blachman, B. A.I(1991). Does phoneme awareness training in kindergarten make a dit~

ference in early word recog

t.tion and developmental spelling? Reading Reuarch Quarterly, 26,

49-66.

Barnhardt, J. E. (1991). Criterio, -related validity of interpretations of children's performance on emer-gent literacy tasks. Journal of Reading Behavior, 23(4),425-444.

Baskt, K., & Essa, E. L. (l990)! Emergent writers and editors. Childhood Education, 66, 145-150.Beals, D. E., De Temple, J. M.,

~

Dickinson, D. K. (1994). Talking and listening that support early liter-

acy development of children from low-income families. In D. K. Dickinson (Bd.), Bridges to liter-

acy: Children,familie.f and. chool.f (pp. 19-40). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Blachman, B.A., Ball, E. W., Black, R. S., & Thngel. D. M. (1994). Kindergarten teachers developpho-neme awareness in 10W-inCO

f

' e, inner-city classrooms. Reading and Writing, 6, 1-18.Bradley, L., & Bryant, P. (1983 . Categorizing sounds and learning to read: A causal connection. Na-

ture, 301,419-421.

Brownell,R. (2000).Expre.f.fiv One-WordPicture VocabularyTe.ft manual (3rd ed.).Novato CA:Aca-demic Therapy. I

Byrne, B., & Fielding-Barnsley! R. (1989). Phonemic awareness and letter knowledge in the child's ac-

quisition of the alphabetic ;~nciple. Journal of Educational P.rychology, 81, 488-313-321.

Byrne, B., & Fielding-Barnsld, R. (1990). Acquiring the alphabetic principle: A case for teaching rec-

ognition of phoneme identitt. Journal of Educational P.rychology, 82, 805-812.Byrne, B., & Fielding-Barnsley, R. (1991). Evaluation of a program to teach phonemic awareness to

young children. Journal offucatiOnal P.rychology, 83, 451-455.

Byrne, B., & Fielding-Barnsle , R. (1995). Evaluation of a program to teach phonemic awareness to

young children: A 2- and 3- ear follow-up and a new preschool trial. Journal of Educational P.IY-

chology, 87, 488-503. I

Cunningham, A. E. (1990). ExPlicit versus implicit instruction in phonemic awareness. Journal of Ex-perimental Child P.ryChoIO

~

', 50,429-444.Dickinson, D. K., & Sprague, K. E. (2001). The nature and impact of early childhood care environ-

ments on the language and arly literacy of children from low-income families. In S. B. Neuman &

D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Haiuibook of early childhood literacy re.fearch (pp. 263-280). New York:Guilford.

Fang, Z., & Cox, B. E. (1999

~Emergent metacognition: A study of preschoolers' literate behavior.

Journal of Research in Chil hood Education, 13,175-187.

Griffith, P. L., Klesius, J. P., & omrey, J. D. (1992). The effect of phonemic awareness on the literacy

development of first grade ~hildren in a traditional or a whole language classroom. Journal of Re-

.fearch in Childhood Educa~on, 6, 87-92.Hargrave, A. C., & Senechal, M. (2000). Book reading interventions with language-delayed preschool

children: The bene!its of refar reading and dialogic reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly,

15, 75-90.

Hawken, L. S., Johnston, S. S., & McDonnell, A. P. (2005). Emerging literacy views and practices: Re-

sults from a national survey'ofHead Start preschool teachers. Topic.f in Early Childhood Special Ed-ucation, 24, 232-242. tInternational Reading Associ tion and the National Association for the Education of Young Children.

(1998). Learning to read, d write: Developmentally appropriate practices for young children.Young Children, 53, 3-46.

Juel, C. (1988). Learning to rJd and write: A longitudinal study of 54 children from !irst through fourth

grades. Journal of EdUCati

1

nal P.rychology, 80, 437-447.Justice, L. M., & Ezell, H. K. (2000). Enhancing children's print and word awareness through

home-based parent interve tion.American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 9, 257-269.

EMERGENT LIT CY CURRICULUM 109

Justice, L. M., & Ezell, H. K (2002). Use of storybook reading to in

tease print awareness in at-risk

children. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11, 17 29.

Keppel, G. (1982). De.I'ign and analysis: A researcher'.~ handbook ( nd ed.). Englewood Clifl's, NJ:Prentice Hall.

Lipsey, M. w., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysi.~. Tho

~

sand Oaks, CA: Sage.Lonigan, C. J., Burgess, S. R., & Anthony, J. L. (2000). Developmen of emergent literacy and early

reading skills in preschool children: Evidence from a latent-variab e longitudinal study. Develop-mental P.rychology, 36, 596-613.

Lundberg, 1., Frost, J., & Peters en, O. (1988). Effects of an extensive

logical awareness in preschool children. Reading Research Quarte.

McBride-Chang, C. (1998). The development of invented spelling. Ea9, 147-160.

McCartney, K (1984). Effect of day care environment on children's l~nguage development. Develop-mental P.lycholo!O~ 20, 244-260.

McGee, L. M., & Richgels, D. J. (2003). Designing early literacy programs: Strategie.~FJr at-ri.I'kpre-.~chool and kindergarten children. New York: Guilford.

Nation, K, & Hulme, C. (1997). Phonemic segmentation, not onset-ri

fe segmentation, predicts early

reading and spelling skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 32, 154-1 7.

Neuman, S. B., & Dickinson, D. K. (Eds.). (2001). Handbook of early c ildhood literacy research. NewYork: Guilford.

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, PL 107-110.

Opitz, M. F. (2000). Rhymes and reasons: Literature and language plfiy for phonological awareness.Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Pontecorvo, C., & Zucchermaglio, C. (1989). From oral to written lang,hage: Preschool children dictat-ing stories. Journal of Reading Behaviol; 21, 109-126.

Reid, D. K., Hresko, W. P., & Hammill, D. D. (1989). Te.l.tof Early ~eading Ability, Second Edition(TERA-2). Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

Roberts, T., & Neal, H. (2004). Relationships among preschool Engli~h language learners' oral profi-ciency in English, instructional experience and literacy developm~nt. Contemporary EducationalP.lychology, 29, 283-311.

Roberts, T. A. (2003). Effects of alphabet-letter instructions on you4g children's word recognition.Journal of Educational P.rychology, 95, 41-51.

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to

f

ater reading (dis)abilities: Evi-

dence, theory, and practice. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Bds ), Handbook of early childhoodliteracy research (pp. 97-110). New York: Guilford.

Schatschneider, c., Fletcher, J. M., Francis, D. J., Carlson, C. D., & Fo~rman, B. R (2004). Kindergar-ten prediction of reading skills: A longitudinal comparative analys~s. Journal of Educational P.ry-chology, 96, 265-282.

Snow,C. E., Burns,M. S., &Griffin,P.(Eds.).(1998).Preventingreadi¥g difficultiesin young children.Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Sophian, C. (2004). Mathematics for the future: Developing a Head St~ curriculum to support mathe-matics learning. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 19, 59-81.

Stanovich, K. E., Cunningham, A. E., & Feeman, D. J. (1984). Intelligence, cognitive skills, and early

reading progress. Reading Re.I'earch Quarterly, 19, 278-303. 'ISulzby, E., Barnhart, J., & Hieshima, J. A. (1989). Forms of writing an1 rereading from writing: A pre-

liminary report. In J. M. Mason (Bd.), Reading and writing connect

1

on,I' (pp. 31-61). Boston: Allyn& Bacon.

Treiman, R., & Baron, J. (1983). Phonemic-analysis training helw children benefit from spell-ing-sound rules. Memory and Cognition, 11, 382-389.

Treiman, R, & Rodriguez, K (1999). Young children use letters in learping to read words. P.rychologi-cal Science, 10,334-338.

)rogram for stimulating phono-'y, 23, 263-284.

ryEducation and Development,

110 DEBARYSHE AND GORECKI

D.S. Department of Education. ~2005). Fiscal year 2005 applicationfor n~'Wgrants to the Early Read-

ing First Program. Retrif1Ved January 3, 2004, from http://www.ed.gov/pIOgrams/earlyre

ading/2005-359a.docVellutino, F. R., & Scanlon, D. '. (2001). Emergent literacy skills, early instruction, and individual dif-

ferences a.~determinants of .fticulties in learning to read: The case for early intervention. In S. B.Neuman & D. K. Dickinson Eds.), Handbook of early childhood literacy research (pp. 295-321).New York: Guilford.

Whitehurst, G. J., Arnold, D. S., Epstein, J. N., Angel!, A. L., Smith, M., & Fischel, J. E. (1994). A pic-

ture book reading interventio in day care and home for children from low-income families. Devel-

opmental P.rychology, 30, 67 -689.Whitehurst, G. J., Falco, F. L., nigan, C. J., Fischel, J. E., DeBaryshe, B. D., Valdez-Menchaca, M.

C., et al. (1988).Acceleratin. language development throughpicture book reading. Developmental

P.lychology, 24, 552-559.Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan,

.

C

t

J. (2001). Emergentliteracy:Developmentfromprereaders to readers.In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Di kinson (Eds.), Handbook of early litera~y research (pp. 11-29). NewYork: Guilford.

Yeh,S. S. (2003).An evaluatio of twoappIOachesfor teachingphonemic awareness.Early ChildhoodResearch Quarterly, 18, 513 530.