Dreaming and Film Viewing - Roger Cook.pdf

Transcript of Dreaming and Film Viewing - Roger Cook.pdf

-

Correspondences in Visual Imaging and SpatialOrientation in Dreaming and Film Viewing

Roger F. CookUniversity of Missouri

New directions in film and media theory have begun to focus on precognitive,embodied aspects of film viewing. Drawing on these recent theoretical ap-proaches, this article examines correspondences between the brainmind stateof the dreamer and the film viewer and formal similarities between thecinematic image and dream images. First, the study asks whether cinemasevolution toward the production of images that are more easily processed bythe brain has also made film images easily accessible during dream-sleep.Then it shows how the cinematic image and the visual imaging of dreamsdepend on a similar construction of navigable space. The analysis suggeststhat the bodily systems for simulating movement and establishing spatialorientation function in a similar manner during dreaming and film viewing.

Keywords: dreaming, cinema, film theory, spatial cognition, spatial orientation

The time is ripe to start laying the groundwork for a new exploration of cinemaand dreaming. The connection between the two has long been documented both byfilm scholars and dream researchers. Particularly in film criticism, the similaritybetween the film experience and dreaming has figured prominently. Film scholarshave frequently emphasized how the setting of a darkened movie theater where theviewer sits quietly while a stream of visual images synchronized to sound areprojected onto a large screen parallels the situation of the dreamer in its formalaspects. Dream researchers have also noted this connection. Not surprisingly, thepsychoanalytical study of dreams figured prominently in this regard. Lewin (1946)famously asserted that dream images are projected onto a dream screen, a blankbackground that is analogous to the motion picture screen. Despite the abundanceof work citing the relation between the two, the scope of study has been relativelynarrow. The attention to the common features of dreams and movies has beenconcerned largely with content (including its formal aspects) and has focusedmainly on the way dreams are represented in cinema. As a result, the film as texttook center stage, whereas the act of viewing and the bodily engagement with thefilm medium remained largely unexplored.

My call for a new approach takes its impetus from new impulses in film andmedia theory. The theory that has dominated film criticism over the past 4 de-

This article was published Online First May 2, 2011.Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Roger F. Cook, Department of

German and Russian Studies, 451 Strickland, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211. E-mail:[email protected]

89Dreaming 2011 American Psychological Association2011, Vol. 21, No. 2, 89104 1053-0797/11/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0022866

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

cadesand still retains much of its influenceis grounded in the discourses ofsemiotics and psychoanalysis. Approaches of this kind analyze the relation betweenthe viewer and the film primarily as a form of textual communication and thusoperate on the level of cinematic representation. More recently, scholars havebegun to focus on the precognitive, embodied response of the spectator and toexamine the film experience as a complex interplay of cognitive, perceptual, affec-tive, aesthetic, and media factors. In this article, I draw on these new directions infilm and media theory to explore correspondences between the cinematic imageand the kinematic imagery of dreams.

With this turn to a film theory of embodiment I hope to engage dream sciencein a mutually meaningful dialogue. There was a similar attempt to bring filmcriticism into a constructive collaboration with dream research at the beginning ofthe 1980s. The centerpiece of this effort was the journal Dreamworks, founded byfilm scholar Marsha Kinder. This concentrated, programmatic project was short-lived (19801988) for, I think, primarily two reasons. First, the input from filmscholars and theorists was grounded almost exclusively in what has been and stillremains the overwhelmingly dominant approach to understanding dreams amonghumanistsFreudian dream analysis. Second, the focus from the side of filmscholars and filmmakers was almost exclusively on the level of content. This wastrue whether the issue was the plausibility of dream sequences in films or theaffinities of dreams and film more generally. But also the neuroscience contributionto the journal failed to get to the crux of embodied spectatorship. In his attempt ata systematic comparison of the Dream State and the Film State in the first issueof Dreamworks, Hobson (1980) compared dream neurobiology with cinemasability to simulate the various body states and brain modalities onscreen (pp.1517). In other words, he compared the filmic representation of the dream statewith the body state of the dreamer. Another approach, one I take here, is tocompare the body state of the film viewer with that of the dreamer.

In this article, I first address the broader question of how feature films haveevolved so that their spatial and temporal substrate dovetails with the nervoussystems own innate neurobiological predispositions (Neidich, 2003, p. 92). Ac-cording to the media theory that informs my analysis, this tailoring of the cinematicimage to a higher order of visual and cognitive processing enables it to bypass someof the discrete neural processes of mental imaging and correspond more directlywith what Damasio (1999) has famously termed the movie-in-the-brain (pp. 9,1112). I analyze this aesthetic and technological development with respect to thefollowing question: Does the visual and cognitive ergonomics of the cinematicimage make it readily accessible to the brainmind in the state of dream-sleep?

In the second part of the article, I examine how the construction of space andmovement in mainstream narrative cinema relates to those elements in dreamimagery. I focus on these featuresrather than, for example, narrative or repre-sentations of the selfbecause they play a foundational role in both dreaming andcinema. The visuomotor aspect of dreams depends on the movement of the selfthrough a spatially visualized dream scene (Hobson, 1999, p. 170). Just as normalspatial cognition is essential for dreaming (Solms, 2003, p. 56), the simulation ofreality in cinema also depends on the construction of a navigable narrative space.My analysis of this correspondence leads to a discussion of similarities in the

90 Cook

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

neurophysiological state during dreaming and film viewing and to conclusionsabout the way the brainmind establishes spatial orientation in each case.

THE VISUAL AND COGNITIVE ERGONOMICS OF THECINEMATIC IMAGE

To explain how the novice or young film viewer can immediately understandmovies despite their spatiotemporal discontinuities, McGinn (2005) asserts, Inwatching a movie a child is exploiting the cognitive machinery already madeavailable by the dream mechanism (p. 113). Although I agree with the wayMcGinn sketches the affinities between the two, I disagree with his suggestion thatour dream experiences are a prerequisite for the apprehension of film as a coherentrepresentation of reality. Rather, I think the minds ability to produce the unitaryflow of images that comprise waking consciousness entails all the cognitive skillsneeded to see film as a coherent form of visual imaging. Indeed, the global successof cinema stems from its ability to shape the moving images of film into a productthat mirrors the mental imaging of consciousness. Because the technologicallyproduced moving images of film can be both visually and spatiotemporally shaped,structured, and distorted according to the imagination of the filmmakers, they bearthe strong resemblance to dreaming cited by McGinn. But rather than claim thatdreaming enables us to comprehend movies, I want to suggest that cinema has hada profound effect on both the content and form of our dreams. In other words,cinema has developed an ergonomic efficiency that makes movies not only easilycomprehensible to the waking mind but also readily accessible to the neuralprocesses that produce dream imagery.

When we speak of the ergonomics of an image, we mean its efficiency ininterfacing with the systems of visual processing in the brain. As in its commonusage regarding equipment in the workplace, ergonomic efficiency refers here to theability to design optical devices so that the images produced can be processed withminimal fatigue and stress. When applied to technologically produced visual im-ages, this includes more than just the processing in the visual cortex. In contrast todesign features that position the hand more efficiently with respect to the keyboard,for example, an ergonomics of mediated visual images must take into account thehigher order cortical processing of visual information required to produce percep-tion and mental representations of objects or events.

Visual and cognitive ergonomics, a concept I have borrowed from WarrenNeidich, entails a complex interplay between the technological and aesthetic rela-tions that shape the cinematic image and the neural processes that produce themental and visual images of consciousness. Neidich explains how cinema hasdeveloped an increasingly effective phatic image. By this, he means an image thatis able to attract and hold captive the viewers attention to the extent that it cancompete successfully with those that represent our perception of nonartificial, realenvironments (Neidich, 2003, pp. 5759, 8990). As classical editing developed amore efficient use of cinematic time and space, it produced a system of aestheticbinding that effectively mirrors the temporal and spatial categories of naturalperception. In other words, cinema has been able to bypass some of the individualneural processes of mental imaging and to simulate the flow of images that make up

Dreaming and Film Viewing 91

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

consciousness. The aesthetic binding of cinema preselects those images that makeit to phenomenological consciousness. To the extent that it achieves this ergonomicefficiency, it weeds out images that are conscious to the brain without beingconscious to the subject or selfimages that remain beneath the threshold ofphenomenological consciousness.

In the course of this development toward ergonomic efficiency, the opticaldevices for the production of visual images have become better tuned to the bodilyprocess of visual imaging. The technologies and practices for producing visualimages that are best adapted to the neural networks of visual perception areselected and further developed (Neidich, 2003, pp. 5864). Important here for myanalysis of dreams and cinema is that this is a coevolutionary process of selection.As Neidich (2003) put it, these more sophisticated and intense phatic signifiers . . .are pushing out their more unsophisticated progenitors from the visual landscape,in a process similar to natural selectionexcept the real selection is taking place inthe brain as these stimuli compete for the brains neuronal attention (p. 58).According to this theory, as the phatic image of cinema has become widelydisseminated, selection via neural plasticity produces changes in the way the braingenerates visual images. This effect then feeds back into the technological inven-tions and aesthetic principles that continue to shape how the cinematic image istailored to our neural systems for visual processing (Neidich, 2003, pp. 9094).

What effect then does the coevolution of the cinematic image with our neuralsystem for visualcognitive processing have on dreaming? The account I have justgiven of its progressive gain in ergonomic efficiency would seem to suggest that itis well suited for our dream life. Put simply, if cinema is constantly adapting so asto present its audience with images that are easily processed, then we would expectthat those images would present themselves readily to a state of consciousness thatdraws exclusively from internally generated, pseudosensory signals. Kinder (1980)asserted this at the outset of the Dreamworks project in the early 1980s. Sheclaimed that not only are film images readily incorporated into dreams but so areparticular film techniques: newsreels, animation, fades, dissolves, superimposi-tions, freezes, and instant replays (p. 54). And indeed, there is abundant evidencefrom dream reports that dreams frequently look and feel like film sequences.1 Moreextensive and focused dream research on the topic would be needed to produce adetailed, scientifically established account of how film images work their way intodreams and affect their structure and content. That is not the purpose of this article.However, before turning to the possible ramifications of recent film theory for thisquestion, I want to address one particular area where dream research has askedabout the influence of movies on dreaming. I do so to suggest how a fullerunderstanding of the coevolution of the bodily process of visual imaging withmoving image technology and aesthetics might feed into the study of dreaming.

In a series of three related articles, Schwitzgebel (2002, 2003; Schwitzgebel,Huang, & Zhou, 2006) addressed the question of whether we dream in black andwhite. In raising this issue, he was primarily analyzing and questioning the reliabil-ity of reports of dreaming in black and white. As Schwitzgebel showed, by far the

1 When I refer to the appearance of certain style or content elements in dream reports, I am citingreports in Schneider and Domhoffs online DreamBank.

92 Cook

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

highest incidence of such reports was during the 1940s and 1950s when black-and-white films were still prevalent. Then starting in the 1960s, there was an almostdirect reversal, with almost all researchers showing that more than 50% of therespondents reported dreaming in color (pp. 650651). Schwitzgebel argued thatwe should be strongly suspicious of the wave of black-and-white dream reports inthe 1940s and 1950s. He suggested that during that period the familiarity withblack-and-white movies influenced the respondents (pp. 654655).

The primary thrust of Schwitzgebels (2002) argument is a broader claim aboutthe untrustworthiness of our memory about phenomenological experience, espe-cially when it concerns something as elusive and usually inconsequential as dream-ing. He even went so far as to suggest that all dreaming is in color, but that we donot always attend to the color of the objects in the dream (p. 657). All dreamresearchers are of course quite familiar with the difficulty most of us have inremembering much of what occurs in our dreams. Like Schwitzgebel, Hobson(2002) also reasoned that we always dream in color and that reports of dreams inblack and white are a result of one thingpoor memory (p. 43). I would agree thatsome reports were prompted by the ubiquity of black-and-white moving pictures(cinema and TV), as Schwitzgebel claimed, but there is also the distinct possibilitythat during dream-sleep our systems of visual processing internally recall or repro-duce images like those we have viewed so often at home and in the movie theater.If our dreams include such film styles as animation and newsreels and such filmtechniques as superimposition and freezes, then why not also black-and-whiteimages? This would also explain why there would be a spike in instances ofdreaming in black and white during the 1940s and 1950s. A recent statistical studyseems to support this. It argues convincingly that people who were exposed only toblack-and-white moving images as children are more likely to dream in black andwhiteand that this is not merely a case of faulty dream memory (Murzyn, 2008).There are also frequent accounts of black-and-white photographs appearing indreams (Schneider & Domhoff, n.d.). They often play a key role in the dreamnarrative, and the reports usually identify them positively as being black-and-whiteand not color prints. Here the evidence seems more conclusive that these areimages of stills developed from black-and-white film and not just photos of inde-terminate color. And if our dreams can include images of black-and-white stills,why would we think that they cannot contain sequences of moving images in thesame color format?

Another way to approach this matter is with a slightly different question. Dowe dream in Technicolor? Technicolor was a series of widely used processes forcolor film production that enabled Hollywood to make films in more richly texturedand more highly saturated colors than those we experience in our perceptions ofreal environments. Films in Technicolor enable us to see the simulated world offilms as more vividly colored than most everyday scenes in reality. It also imbuesfilm viewing with a sense of marvel and emotional intensity that would make filmimages more likely to surface in dreams. The associative link between the emotionsand images in Technicolor would render them prime material for dreaming. It isthen not surprising that research subjects report dreaming in Technicolor (Sch-neider & Domhoff, n.d.). Indeed, it makes sense that cinemas ability to producethese colors consistently in a sequence of moving images that present a coherent,

Dreaming and Film Viewing 93

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

stabile picture of the external world could enhance the vivid sensations of dreamingexponentially.

One of my own most vivid dream experiences attests to this. It was a dream Ihad while still an undergraduate, long before I had an academic interest in dreams.And it was an instance of lucid dreaming that I have only recently come torecognize as such. In the dream, I was standing in front of and looking into afantastic world where everything was in Technicolor. It was not as if I werewatching a film but rather as if the most vividly colored film world had materializedfully in front of me and was beckoning me to enter. I was aware that I had to bedreaming, but I also realized that I could choose to step into this world andexperience it as reality. When I did, I felt a sense of exhilaration and wonder as Iwas able to move through it as if I were indeed in a world that surpassed the realone in beauty and brilliance. As I discovered that I could also prolong the experi-ence, I felt a sense of empowerment that enhanced it even more. When I awoke,what remained with me were these feelings and an overall sense of the beauty I hadencountered, rather than any particular objects, people, or events. There was, asLaBerge and Rheingold (1990) have said about first lucid dreams, a feeling ofhyperreality that happens when you take a good look around you in the dream andsee the wondrous, elaborate detail your mind can create (p. 127). This was thefeeling I retained from the dream, with one important difference. I attributed thepower to create this world, which appeared after all in Technicolor, to cinema andnot my own mind. This did not happen only afterward but rather, during the dream,I recognized that this was a world created by cinema and marveled at its ability tomake something of such visual intensity accessible to real experience. From thebeginning, the film industry was clearly aware that Technicolor could help evokethis sense of participation in an alternative reality. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer selectedThe Wizard of Ozbilled as its Technicolor Triumphto be its first big-budgetproject using this color process that would win over film audiences to the newtechnology and to a new, more vividly colored perception of reality.

My discussion of black-and-white and Technicolor images in dreams impliesthat the phatic image of cinema can make itself directly available to the internallygenerated representations of reality during dreaming. That is, film images drawnup from memory seem to be able to override the binding that typically gathersdiscrete sensory images into our visual, colored images of consciousness. Just as thevisual imagery of dreaming can lack the input of various dispositional representa-tions that contribute to mental imaging, it would seem that it can also include intactimages previously committed to memory. In the case of my own Technicolor dreamexperience, it may well be that the hybrid state of consciousness that produces luciddreaming enhanced the brains ability to call up the intact visual imagery of anelaborate film world. That is, the association of wake-like frontal lobe activation. . . with REM-like activity in posterior structures (Voss, Holzmann, Tuin, &Hobson, 2009, p. 1199) enabled the recall of already assembled visual images. Andat the same time, the cognitive recognition of those records as film images may haveboosted the visual buffers ability to incorporate and organize the images generatedin the visual associative cortices (cf. Occhionero, 2004, pp. 5960). In any case,what makes film images easy for the brain to process, that is, their cognitive andvisual ergonomic efficiency, would seem to make them particularly accessible to thebrain during dreaming as well.

94 Cook

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

SPACE AND MOVEMENT IN DREAMS AND FILM

The scientific study of dreaming has long recognized the movement of the selfthrough a visually imagined space as a key feature in our dreams. In fact, this aspectof dreaming enabled researchers to anticipate later findings in movement physiol-ogy about the brains ability to predict outcomes of enacted body movement. AsHobson (2002) pointed out, Hermann Helmholtz inferred from the brains abilityto simulate movement during dreaming that the nervous system created its ownimage of the expected consequence of movement (p. 30). As neuroscience hasdetermined some of the brain regions and processes involved in the production ofthe efferent copy of movement outcomes, it has explained how the movement ofthe self in dreams is produced by the same systems that guide movement duringwaking experience. And it has declared that these systems function in the samebasic manner as when guiding our actual movement (Hobson, 2001, pp. 183188).

At first glance, these findings might lead one to assume that cinema canproduce only a weak copy of the simulated experience of movement as it isproduced both in dreaming and when awake. I would argue, however, that in someways the bodys response to the simulated movement of film resembles that duringdreaming quite closely. Dream research has, I think, underestimated cinemasability to engage the viewer physically in its movement. Hobson (2002), for exam-ple, claimed that even the most technically sophisticated film cannot evoke thefictitious experience of movement typical in dreams (p. 146). Here, I think heoverstates the difference between dreaming and cinema. A closer analysis of howthe movement in and of film affects the viewer will suggest strong similarities.

First, we turn to movement in the film. The movement of people and objectswithin the cognitively constructed space of the film world can generate strongkinesthetic responses. The classic chase scene through the hilly streets of SanFrancisco in Bullitt offers a prime example. The cars flying through the air as theyspeed up and down the hills of San Francisco produce a strong kinesthetic feeling.The movement and kinematic sensation experienced in this scene are enhanced byan invisible avatar of the viewer that moves within the cognitively mapped space ofthe film world. To produce this effect, the camera was positioned so as to simulatethe viewers presence in the cars. The embedded viewer, as I call this invisible avatarof the film viewer, serves then as a conduit through which the physical sensation isconveyed to the actual viewer in the movie theater. From the very onset of whatwould become classical or mainstream narrative cinema, the dominant film practiceworked to create this position for the viewer within the film. In this way, narrativecinema constructs a virtual space that holds at least the potential for active sensoryexploration. This mode of actively engaging sensorimotor functions requires aninterface between the spatial configuration of the virtual film world and the viewersituated in the darkened movie theater. The eye of the camera provides such anentry. In classical cinema, its basic visual unit is an anthropocentrically organizedimage, one that the movement, framing, and point of view of the camera structureso as to produce an open and available human perspective within the narrativespace of the film. In its imagined physical construct, this point of view assumes theeyeline of an adult human who is present in the film scene. The viewer is then drawninto the scene rather than viewing it from outside as if through the frame of awindow.

Dreaming and Film Viewing 95

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

Assuming this ready-made position within the film world, the viewer respondsthen physically to the call for potential action it produces. In this respect, theconstruct of the embedded viewer corresponds to the variously represented pres-ence of the self in dreams. Whereas the dreamer at least knows and usually sees hisor her self involved in the dream, the embedded viewer remains invisible andseemingly detached. Still, even as an invisible avatar, this subject position enablesthe viewer to physically experience simulated movement in much the same fashionas the dreamer. The basis for the sensation of movement is a cognitively mappedspatial orientation and a stable point of view within the film. Tracing the emergenceof a narrative syntax around 1906, Gunning (1984) described how the new approachsacrifices linear temporal continuity for spatial continuity. In this new cinema ofnarrative integration, spatial mapping became the foundation for the narrative filmworld. The result was a coherent synthetic geography (Gunning, 1984, p. 108)that served to control the viewers embodied responses to its own virtual movementin the film and to the movement of objects around it.

There is a significant correspondence between the way spatial mapping andmovement are structured in dreaming and cinema. Solms (1997), in his study of theeffect of different brain lesions on dreaming (pp. 104105), and Foulkes (1999), inhis study of the emergence of dreaming in children (pp. 7678), both argue thatvisualspatial cognitive abilities are essential to the production of kinematic visualimagery in dreaming. Drawing on case studies of right parietal damage in themedial occipitotemporal region, Solms concluded that concrete spatial cognition. . . is the grounding medium within which the quasispatial (symbolic) operationsoccur (pp. 240241). The important role that spatial construction plays in thestability of cinematic imagery and narrative closely parallels the foundationalaspect of spatial cognition in dreaming. For his purpose of stressing the primacy ofabstract thinking in the dream-generating process, Solms focused on the relationbetween spatial cognition and the quasispatial (symbolic) operations activated inthe left parietal region.

However, Solmss (1997) work shows that cognitive spatial mapping is requiredfor the visual expression of other modality-specific memory systems (p. 239) aswell. The modality of main interest for my analysis is motion relations. Arguingbackward from Solmss finding, we might infer that the steady flow of film imagescould evoke an experience of fictive movement similar to that experienced indreams. This kinematic aspect of film has begun to gain new attention in cinemastudies. Recent film theory has begun to argue the centrality of movement, over andagainst a cinematic realism that describes cinema as a window onto the world ora psychoanalytic film theory that focuses on the semiotic system of structured looks.New work has stressed that even when the dominant film aesthetic strives forspatial continuity and stability, kinesthetic responses are always at play in filmviewing. A recent article by Curtis (2008) supports this new perspective with anargument drawn from kinetic theory. Curtis explains how the motion in and of thecinematic image creates depth according to kinetic occlusion versus the staticocclusion that results from the overlapping of objects in a (still) photograph (pp.254255). The motion of objects relative to one another within the frame producesa kinetic sense of depth similar to what guides our bodys movement through realenvironments. In another recent article that does much to restore the importanceof movement in film analysis, Gunning (2007) points out that we experience

96 Cook

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

kinesthesia most strongly when our own body moves, but we can also feel thesensation when we watch an object move, including an object in a film (p. 43). Heclaims, for example, that watching a moving object in a film, such as a ball rollingdown a hill, produces a kinesthetic sensation in the viewer. In less complex casessuch as this, it is questionable whether a virtual body projected into the space of thefilm augments the physical response in the viewer. However, when the construct ofan embedded viewer becomes involved, more complex kinesthetic sensations arepossible, particularly when the film sets it into dynamic motion. The construction ofa moving point of view within the space of the film enhances, for instance, thedizzying kinesthetic sensation felt during the car chase in Bullitt. In her account ofthe kinetic occlusion produced by moving objects, Curtis explains how the move-ment of the invisible body of the embedded viewer (the body schema) generatesthis effect. Using a referential term from linguistics, she refers to this simulatedpresence of the viewer as the emplacement of the filmic origo (die Verortung derfilmischen Origo; p. 250).

What I want to examine here is the correspondence between the activation ofbodily senses of motion in the film viewer and the bodys responses to the internalimaging of fictive movement in dreaming. An important distinction is that in film wehave both the fictive movement of objects and people within the simulated realityof the film and also the real movement of the film image. The latter is onlybeginning to get its due. In his article on film movement, Gunning (2007) takes amajor step in this direction. Emphasizing the complete media environment ratherthan the film as merely a text, he resists the reductionism of the dominant theo-retical approaches (semiotics, psychoanalysis, cognitivism). Where each of theseemphasizes the illusion of reality created by cinema, Gunning focuses on movementas the key element that enables film to produce a strong impression of reality (pp.4044). As opposed to the sense of the past that we have from the indexicality ofthe photograph, Gunning argues, the movement of the cinematic image draws us into participate with the film as a present reality. As he puts it, to perceive motion,rather than represent it statically in a manner that destroys its essence, one mustparticipate in the motion itself (p. 42). The impression of reality this generates iswhat gives the term diegesis its particularly filmic connotation. That is, filmicdiegesis goes beyond the more narrow meaning of just a narrated world to alsoinclude a sense of immediacy and presence. The moving images of cinema initiatea perceptual response and affective participation in the image.

Gunnings description of how film diegesis creates a sense of presence chal-lenges traditional notions of the lack of sensorimotor activity in film viewing.The impression of reality that activates sensorimotor systems does not depend onthe movement of objects or of the embedded viewer in the film world. Rather, theadvancing present constituted by the moving images of film engenders in and ofitself perceptual and affective participation (Gunning, 2007, p. 40). Thus, in bothdreaming and film viewing, the initiation of sensorimotor activity is crucial to theexperience. Using the same phrasing that Revonsuo (2003) applied to dreams, wecan say that film produces in the viewer the mental imagery of motor actions andactivates the same motor representations and central neural mechanism that areused to generate actual actions (p. 97).

And yet, dream research has used just this aspect to demarcate the limits ofcinemas ability to simulate dreaming. Hobson (2002) maintains that dreams in-

Dreaming and Film Viewing 97

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

clude fictitious movement of a type not yet simulated easily, even in the mosttechnically sophisticated film. He then argues, Only virtual reality, where thesubjects own movements affect perceptions, comes close to this dream experience[of fictitious movement] (p. 146). However, with respect to the action generated inresponse to fictitious movement, dreaming is more closely aligned with cinema thanwith virtual reality systems. In dreaming, as in film viewing, there is an inhibitionagainst responding actively to simulated movement. In virtual reality environments,the point is that you do respond to them. The stop-action mechanism at work in filmviewing is of course activated differently than in dreaming. During sleep, theinhibition of muscle function (atonia) keeps the body from responding actively tothe movement scenarios exhibited in dreams. Film viewing requires in part alearned inhibition against actively responding to the events depicted on screen.Still, the neurophysiological impulse to act is always triggered, only to be inhibitedby stop-action commands. In stressing the universality of this embodied response tofilm, Metz and Guzzetti (1976) declared that there are two types of motor outburst[during film viewing], those that escape reality testing and those that remain underits control (p. 76). In other words, the viewers body produces at each momentefferent signals that predict the sensatory data it will receive in its next position andprepare the body to take the appropriate action. Regardless of how the stop-actioninterdiction is carried out, participation in the advancing reality of the film activatesthe affective and perceptual networks associated with episodic memories. Eventhough motor responses are restricted by the cultural practices of cinema, thishappens on top of the base level of a nervous system already poised for action bythe movement of the film image.

Gunnings recent work adds this important dimension to other theoreticalwork on embodied aspects of film spectatorship. And yet, he does not incorporateinto his analysis the moving visual point of view of a phenomenological subjectemplaced in the film. Sobchacks (1992) elaboration of this internal viewing positionin her Address of the Eye: Phenomenology of Film Experience in the 1990s openedup new vistas on the question of movement and embodied viewing (pp. 205207).For example, Curtis explanation of how kinetic occlusion works in film space isgrounded in Sobchacks work, as is my own conception of the embedded viewer.However, in the case of both Gunning and Sobchack, the emphasis is on kinesthe-sia. There is another physical response in the film viewer, one that has not receivedmuch attention in either film theory or dream researchproprioception. Here, Iwant to ask how Gunnings account of film movement, when combined with thephenomenological construct of an embedded viewer, might apply to the waycognitive and proprioceptive modes of spatial orientation work together in filmviewing and in dreaming.

There are two modes of spatial orientation that function jointly to enable us tomove through the world effectivelycognitive mapping (CM) and proprioceptivespatial orientation (PSO; Mitchell, 2010). Our ability to create cognitive maps andthen situate our bodies within a visually represented three-dimensional space is themore dominant system in most human activities and has been the main focus ofspatial orientation studies. Recently, more attention has been given to the role theproprioceptive system plays in our ability to move effectively within our immediateenvironment. Responding to the movement of the body through an indeterminatespace, the PSO does not employ visual referencing of external objects to each other.

98 Cook

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

Dependent on feedback from the internal status of the body, proprioceptioncontinually reworks neuronal flows marking the movement of parts of the body intoa continuous information feed about the position of the body as a whole (Sheets-Johnstone, 2010).

CM always works in tandem with PSO, but the deployment of one system oftenrequires that the other be largely deactivated. Because of the inhibition againstphysical action, CM dominates in both film viewing and in dreaming. The aestheticsof mainstream narrative cinema have further cemented the dominance of CM in thefilm viewer. When the cinema of narrative integration took shape in the first 2decades of the previous century, the camera was limited to fixed positions. The cutfrom one shot to the next established the continuity of time, space, and action, butit did so from a continuous series of stationary points of view. The movementbetween fixed camera shots is largely eliminated, thus carving up the narrativespace into compartmentalized segments observed from clearly established points ofview. This promotes CM and suppresses the stimulation of proprioceptive feedbackthrough the simulated movement of the embedded viewer. Thus, the solidificationof narrative integration promoted exteroception and representational realismrather than an activated sensorimotor system and embodied engagement with thespatial world of the film.

In contrast to the real world, where proprioception plays a greater role invisual orientation, in mainstream narrative film, visions dominance over the othersenses is accentuated. Nonetheless, proprioception always works in conjunctionwith CM and is actively involved in film reception as well (Sheets-Johnstone, 2010,pp. 330331). Anderson (1996) claims that because vision dominates the spatialcognitive system, it is possible to enter the diegetic space of a motion pictureeffortlessly by way of the visual system without the necessity of proprioceptiveconfirmation (p. 113). I would caution that his wording here seems to suggest acleaner break between the two than ever actually occurs. Crary (1999) provides acorrective adjustment to Anderson that is important for my analysis of the simi-larities between dreaming and cinema: Perception is always an amalgam ofinformation from immediate tactile receptors and distant optical and auditoryreceptors, and distinctions between the optical and the tactile cease to be significant(or could only have significance for an impossibly motionless subject with no liverelation to an environment). Vision as an autonomous process or exclusivelyoptical experience becomes an improbable fiction (p. 352).

In dreaming, as in cinema, CM seems to dominate spatial orientation evenmore strongly than in waking life. The works by Solms and Foulkes discussed abovesuggest that it has a primary role in the generation of dream imagery. However,PSO is also at work in dreaming and even takes over almost exclusively at times. Toillustrate this, I turn to a recent dream of my own (February 9, 2010):

I am showing off my chefs knife to someone. The person is not well defined, and I have nosense of who it is. I am holding the knife in my right hand and running my left hand up anddown the blade, with the blade between my fingers and thumb and the sharp edge toward mypalm. Then I am repeating this with a second person, who is also not well defined andunknown to me. And finally I am showing it off in the same manner to a third unknownperson. While I am doing so, the blade slips out of my right hand, and the blade begins slidingquickly through my left hand. The dream goes blank (there is no visual imagery as the knifeis falling). I then feel a strange sensation in the ring finger of my left hand. I look at it andsee that the knifes blade has stuck in the callous inside my ring finger at the middle joint and

Dreaming and Film Viewing 99

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

that the knife is hanging from the finger. When I see the knife hanging there, I feel the fingerfirst twitching and then moving back and forth. I wake up at this point, and my ring fingeris in fact twitching and moving back and forth.

Throughout the dream, the visual imagery of the scene is not well elaborated.The location is not defined in any way, and the only visual images are vague onesof the other person and the knife in my hands. Visuospatial cognition is alsominimally activated. In each iteration, the other person is merely out there some-where, with no clear relation to my own position. And yet the dream was forcefuland memorable because of its vivid imagery.2 Somatosensory and somatomotorimages dominate (cf. Solms, 2003, pp. 5556). The focus is almost entirely on theknife and the movement of my body in relation to it. Even the knife was notarticulated well as an object. There was rather a weakly elaborated visual image ofthe blades hard steel surface that made a strong tactile impression. In this case, thehaptic impression combines with the single visual element to express the strongemotional associations connected with the scene. At first, the feeling of priderepeated three times as I showed off the knife to each person. And then there wassudden fear when the knife began to fall, and finally horror as I saw it hanging frommy finger.

Dreams such as this one suggest that CM and PSO work in a more stronglyhinged relationship during dreaming than during film viewing. That is, when onecomes to the fore, the other tends to recede more fully. When the knife begins tofall, the visual imagery disappears altogether, and the dream remains blank longerthan it would take the knife to fall this short distance. In keeping with Foulkes andSolms emphasis on spatial cognition as the prerequisite for kinematic visualimagery, the absence of all visual images suggests that the proprioceptive orienta-tion of my body to the knife (PSO) takes over when it begins to fall. The visualimage returns only when the knife has stopped and PSO is no longer dominating.In cinema, the uninterrupted flow of images and the cinematically constructedspace enable CM to operate rather seamlessly. To simulate dreams effectively,cinema would then need to do more than present the symbolic narrative content ofdreams in the grounding medium of cognitively visualized space. It would requiredisruptions in spatial continuity, including gaps in the otherwise constant flow ofcognitively mapped images, to generate in the viewer some of the physiologicalfunctions that feed into the visual imagery of dreaming.3

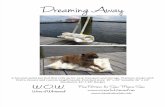

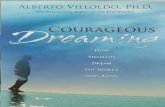

For a classic example of such a tactic, we can take the famous dream sequenceof the fall from the church tower in Hitchcocks Vertigo (see Figure 1). As Scottie(James Stewart) is experiencing vertigo in his dream (see Figure 2), Hitchcockshows a pulsating schematic representation of the view down into the church towerfrom the top of the stairs. It alternates between blue and red while a close-up of

2 I follow here the recent and I think important practice in both neuroscience and the humanitiesof using the word image to refer to images based on any sensory modalitysound images, images ofmovement in spacerather than to visual images only (Damasio & Damasio, 1996, p. 19).

3 Alternative aesthetic strategies can disrupt the dominance of CM and give more room forproprioceptive responses to the film world. In a recent article on Werner Herzogs 1985 film document-ing Rheinhold Messners successful expedition to climb two 8,000-m peaks in the Himalayans insuccession (GasherbrumDer leuchtende Berg [The Dark Glow of the Mountains]), I examine howalternative constructions of film space promote PSO. In the case of Herzogs film, these strategies serveto engage the viewer physically in the mode of spatial orientation essential for the mountain climber(Cook, in press).

100 Cook

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

Scotties face appears and disappears in the middle of the image. Each time the faceappears onscreen, it moves toward the camera before disappearing again, produc-ing the sense of his falling through the space of the tower. The film then cuts fromthis schematic representation of the vertigo effect to a shot of his body falling fromthe tower toward the Spanish tiles on the roof below, where Madeleine (KimNovak) had fallen to her death. At first, we see his body falling toward the tiles,then just the falling body against an otherwise white screen, getting smaller as itfalls away from the camera. At this point, Scottie wakes up before his body slamsinto a hard surface. At no point in the dream sequence is there clear spatialorientation, either with respect to vertical or to any cognitively mapped space at all.A merely schematic representation of the interior of the tower and the blank whitescreen replace spatially mapped visual imagery, producing kinesthetic and propri-oceptive sensations in the place of cognitive orientation.

Figure 1. Vertigo: Hitchcocks representation of Scottie experiencing vertigo in his dream.

Figure 2. Vertigo: Scottie falling from the church tower in his dream.

Dreaming and Film Viewing 101

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

Hitchcocks cinematic representation of Scotties dream corresponds to mypersonal version of the common dream of falling. In my case, I am usually climbingthe kind of free-standing vertical ladder used by daredevil performers who jumpfrom great heights into small tubs of water. I climb the ladder and jump off. Thereis no tub of water at the bottom, apparently only the hard ground, although it isnever directly visible in the dream. While falling, I black out in the sense thatthere are no visual images during the fall, rather only the sensation of falling. Icome to, stunned and staggering around. There is, however, no visual imagery,not even a ground or horizontal surface carrying the weight of my body, only thedizzy physical sensation produced by the circular movement of my staggering body.I stagger until I start climbing up the ladder again to go through the sameexperience repeatedly, until I wake up. This sensation (or somatosensory image)does have a spatial element to it; however, it is a proprioceptive one that is notexpressed visually.

The examples here from Vertigo and my dreams are extreme cases of the roleproprioception can have in cinema and dreaming. Despite the momentary lapse ofvisual imagery, CM continues to cofunction with PSO in all these instances. A senseof ones self moving through a cognitively perceived space, even when it is notvisually expressed, is a precondition for these virtual experiences (Hobson, 1999, p.170). In dreams, it is the variously formed, but inevitably included self-represen-tation of the dreamer that makes CM possible. In cinema, it is the embeddedviewer.

CONCLUSION

In this article, my discussion of the influence that cinema has on our dreamsdraws mainly from recent film theory, on the one hand, and findings in neuroscienceabout the state of the mindbrain during dream sleep, on the other. I had to relyon mostly anecdotal evidence of the way film images, techniques, and narrativesturn up in dreams. One hope in this attempt to engage dream research on the topicof cinema is that it could lead to the collection of hard data about the prevalenceand form of film (and new media) images in dreams. Among other things, thesedata could provide insight into the coevolution of the neural processes that gener-ate the image flow of consciousness and the technological and aesthetic develop-ment of moving-image media.

In my effort to establish similarities between the neural processes that producedreams and those at work during film viewing, I chose to focus on visuospatialmapping and movement. By highlighting this correspondence, I was attempting toexpand our sense of how films can replicate the dream experience and how filmimages might work their way into our dreams. This discussion touched on a numberof other shared elements where a comparative analysis could also prove fruitful.Most notably, the issue of spatial construction also entailed at every turn thephenomenological question of how the self figures into dreaming and film recep-tion. A focused study of the way the self is represented in dreams and in cinemacould help bridge the gap between knowledge about dream-sleep physiology and anunderstanding of the formal aspects of dream consciousness.

102 Cook

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

Finally, there is another aim of this study, one that I have not mentioned. Theemphasis here has been on what the comparison of the neurophysiological states ofdreaming and film viewing might have to offer dream research. The other hope isthat this dialogue will spur new approaches in the critical study of film theory. Iexpect that responses from cognitive scientists and dream researchers to my spec-ulative foray into dream science might well offer valuable insights for theories ofembodied film spectatorship.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J. D. (1996). The reality of illusion: An ecological approach to cognitive film theory. Carbon-dale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Cook, R. F. (in press). Spatial orientation and embodied transcendence in Werner Herzogs mountainclimbing films. In S. Ireton & C. Schaumann (Eds.), Heights of reflection: Mountains in the Germanimagination from the middle ages to present. Rochester, NY: Camden House.

Crary, J. (1999). Suspensions of perception: Attention, spectacle, and modern culture. Cambridge, MA:MIT Press.

Curtis, R. (2008). Deixis, Imagination und Perzeption: Bestandteile einer performativen Theorie desFilms [Deixis, Imagination and Perception: Elements of a Performative Theory of Film]. In H.Wenzel & H. Jager (Eds.), Deixis und Evidenz [Deixis and Evidence] (pp. 241260). Freiburg:Rombach.

Damasio, A. (1999). The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. SanDiego, CA: Harcourt.

Damasio, A. R., & Damasio, H. (1996). Making images and creating subjectivity. In R. Llinas & P. S.Churchland (Eds.), Mindbrain continuum: Sensory processes (pp. 1927). Cambridge, MA: MITPress.

Foulkes, D. (1999). Childrens dreaming and the development of consciousness. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press.

Gunning, T. (1984). Non-continuity, continuity, discontinuity: A theory of genres in early film. IRIS,2(1), 101112.

Gunning, T. (2007). Moving away from the index: Cinema and the impression of reality. differences: AJournal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 18(1), 2952.

Hobson, J. A. (1980). Film and the physiology of dreaming sleep: The brain as camera-projector.Dreamworks, 1(1), 925.

Hobson, J. A. (1999). The new neuropsychology of sleep: Implications for psychoanalysis. Neuropsy-choanalysis, 1, 157183.

Hobson, J. A. (2001). The dream drugstore: Chemically altered states of consciousness. Cambridge, MA:MIT Press.

Hobson, J. A. (2002). Dreaming: An introduction to the science of sleep. Oxford, England: OxfordUniversity Press.

Kinder, M. (1980). The adaptation of cinematic dreams. Dreamworks, 1(1), 5468.LaBerge, S., & Rheingold, H. (1990). Exploring the world of lucid dreaming. New York: Ballantine

Books.Lewin, B. D. (1946). Sleep, the mouth and the dream screen. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 15, 419434.McGinn, C. (2005). The power of movies: How screen and mind interact. New York: Pantheon.Metz, C., & Guzzetti, A. (1976). The fiction film and its spectator: A metapsychological study. New

Literary History, 8(1), 75105.Mitchell, R. W. (2010). Understanding the body: Spatial perception and spatial cognition. In F. L. Dolins

& R. W. Mitchell (Eds.), Spatial cognition, spatial perception: Mapping the self and space (pp.341364). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Murzyn, E. (2008). Do we only dream in colour? A comparison of reported dream colour in younger andolder adults with different experiences of black and white media. Consciousness and Cognition, 17,12281237.

Neidich, W. (2003). Blow-up: Photography, cinema and the brain. New York: Distributed Art Publishers.Occhionero, M. (2004). Mental processes and the brain during dreams. Dreaming, 14, 5456.Revonsuo, A. (2003). The reinterpretation of dreams: An evolutionary hypothesis of the function of

dreaming. In E. F. Pace-Schott, M. Solms, M. Blagrove, & S. Harnad (Eds.), Sleep and dreaming:Scientific advances and reconsiderations (pp. 85109). Cambridge, England: Cambridge UniversityPress.

Dreaming and Film Viewing 103

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.

-

Schneider, A., & Domhoff, G. W. (n.d.). DreamBank. Retrieved from http://www.dreambank.net/Schwitzgebel, E. (2002). Why did we think we dreamed in black and white? Studies in History and

Philosophy of Science, 33, 649660.Schwitzgebel, E. (2003). Do people still report dreaming in black and white? An attempt to replicate a

questionnaire from 1942. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 96, 2529.Schwitzgebel, E., Huang, C., & Zhou, Y. (2006). Do we dream in color? Cultural variations and

skepticism. Dreaming, 16, 3642.Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2010). Movement: The generative source of spatial perception and cognition. In

F. L. Dolins & R. W. Mitchell (Eds.), Spatial cognition, spatial perception: Mapping the self andspace (pp. 323340). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Sobchack, V. (1992). Address of the eye: A phenomenology of film experience. Princeton, NJ: PrincetonUniversity Press.

Solms, M. (1997). The neuropsychology of dreams: A clinico-anatomical study. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Solms, M. (2003). Dreaming and REM sleep are controlled by different brain mechanisms. In E. F.

Pace-Schott, M. Solms, M. Blagrove, & S. Harnad (Eds.), Sleep and dreaming: Scientific advancesand reconsiderations (pp. 5158). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Voss, U., Holzmann, R., Tuin, I., & Hobson, J. A. (2009). Lucid dreaming: A state of consciousness withfeatures of both waking and non-lucid dreaming. Sleep, 32, 11911200.

Showcase your work in APAs newest database.

Make your tests available to other researchers and students; get wider recognition for your work.

PsycTESTS is going to be an outstanding resource for psychology, said Ronald F. Levant, PhD. I was among the first to provide some of my tests and was happy to do so. They will be available for others to useand will relieve me of the administrative tasks of providing them to individuals.

Visit http://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psyctests/call-for-tests.aspx to learn more about PsycTESTS and how you can participate.

Questions? Call 1-800-374-2722 or write to [email protected].

Not since PsycARTICLES has a database been so eagerly anticipated!

104 Cook

This

doc

umen

t is c

opyr

ight

ed b

y th

e A

mer

ican

Psy

chol

ogic

al A

ssoc

iatio

n or

one

of i

ts a

llied

pub

lishe

rs.

This

arti

cle

is in

tend

ed so

lely

for t

he p

erso

nal u

se o

f the

indi

vidu

al u

ser a

nd is

not

to b

e di

ssem

inat

ed b

road

ly.