'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

-

Upload

nicephore-juenge -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

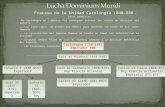

Transcript of 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

1/29

Political Studies

(19 5), X X X I I I , 73 100

om n um in

Thirteenth

and Fourteenth

Century Political Thought and its

Seventeenth Century Heirs:John of Paris

and Locke

J A N E T C O L E M A N *

University

of

Exeter

Dominium, the notion of lord ship, underw ent impo rtant changes during the

thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. An examination of the de potestate regia et

papali

genre, especially the tract by the Dominican John of Paris (1302), i l lustrates

not only a radical att i tude to property rights, private ownership and the defence of

one's own in theory, but reflects important evolutions in contemporary property law

and its conseq uences for secular sovereignty. John of P aris 's analysis of the origins of

property prior to government, based on natural law, is directly related to early

fourteenth-century justifications of the profit economy, reflecting the passage of

dominium from being a relative, interde pen den t, feudal thing, to indepe ndent

property. Other theorists also justified the proliferation of active rights to property,

responding not only to theory but also to current economic and legal practices. Such

arguments were known and used by seventeenth-century writers, especially Locke,

whose library holdings and own tract 'on civil and ecclesiastical power' as well as his

Second Treatise, express a debt to the de potestate regia et papali genre of the late

scholastics.

Thenotion of lordship,

dominium,

in thethirteenth and fourteenth centuries

wasdiscussed in awide variety oftexts that representedaspectrumof literary

genres. These texts attracted different audiences and readerships, defined in

partby the genre:some texts were distinctly literaryin themodernsense,others

werelegal, philosophical, theological.'

ominium

is atheme that has had an

An earlier version of this paper was presented to the Oxford conference on P olitical Th ou ght,

New College, January 1981 and then at the PSA conference, section: medieval poli t ical thought,

Hu ll , April 1981. 1 should l ike to thank A ntony Black, Jam es Burn s, Alan H ard ing , Quentin

Skinne r, D iana P erry , the Oxford University series of seminars on the History of Polit ical Th ou ght,

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

2/29

74

Dominium

in

13th

an d

14th-Century Political Thou ght

enormous significance for the history of political ideas, for the practice of a

transformation of legal theory, for the attitudes expressed by a varied public

their daily transactions at a variety of levels with government and ecclesiastic

representatives. Furthermore, medievaldominium may be directly linked w

seventeenth-century discussions and it is particularly important for Lock

Second Treatise of Governm ent. Dom inium with its related notions

proprietas

possessio

and

usus

sa complicated and shifting series of concep

we shall see, and to affirm that the idea ofdom inium has a history is not to s

it necessarily has a fixed conceptual shape and is used in the same way b

subsequent generations.^ Our set pieces are Latin tracts of the de potestatere

et papali

genre by John of Paris (Ouiddort)his

De Potestate egiaet Pa p

and the anonymous

Rex Pacificus;^

to a lesser extent William of Ockha

Breviloquium

and the

Opus Nonaginta Dierum.

Each of these works w

written quickly, as a scholarly publicist argument in favour of one side, that

the monarchy, in a battle that was a continuous part of the current politic

scenario during the fourteenth century. We shall be brief about what we ma

take to be methodological problems and possible solutions in studyin

fourteenth-century political ideas in general, and thereby indicate ways

which the 'factu al' historian whom Skinner wants to enlist in the 'theory' cau

can be enticed into examining the lesser and greater political theory tracts

gain further insight either into the actual political workings of the age in whic

his author lived, or at least into the mentality that wrote theory, even whe

practice was consciously distinct from the 'ought' implied in the theory text.

will be suggested that a schism between historians of political ideas an

historians of 'facts' and events may be healed by following a

via media

betwe

the internalist and externalist approach to texts and what they were taken

mean in their own time, so far as we can tell.' The method in this study is

suggest that one's approach sdependent first on recognizing the formal chara

teristics of specific genres of political writing and thereafter to discover the rol

of certain genres in the period under consideration.

The attempt to organize fourteenth-century political theorizing by locatin

literary genres is not an artificial organization of chaotic material although

sounds as though it might be. Any student of the written text in the middle ag

is struck by the outstanding degree of imitation involved in putting a te

together: there were explicit/oz-mo for writing kinds of tracts, ranging from

- See Keith Tribe,

Land

Labour and Economic Discourse {London Routledge and Kegan Pau

1978), p. 22, for a differing view on fixed terms of discourse having fixed 'sound' histories but

'meaning' histories. See R. Schlatter, Private Property (London, Allen and Unwin, 1951) for t

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

3/29

JANET COLEMAN 75

to aforma for conveyanc ing, to a topical/or/nc r for satire,

ars dictaminis.

Originality was not particularly

v^ as

admired and composition was

often no m ore tha n a scis sor s-an d-p aste affair, culling quo tes from

ticula r ex am ple of a genre is a successful on e, that is, wh ether it was seen to

. N or d oes a list of genres tell us what a rea de rsh ip s criteria for success

imitative, structured enterprise by which a particular m essage might be

In fact, on e can date texts by know ing the evo lution of a gen re. We

s gen re. Qu ite often, the au th or s aim was not originality of message so much

pro and then sed contra often obscures the au th or s own position: it

forma of the deb ate and thereby know

conclusio, particularly if the

Here we shall focus on one genre:

the publicist pieces d occasion ,

the

forma

(and this directs the con tent) reg arding

versus monarchist debate, a subject and a forma that

Coleman,Medieval Readers

and Writers,

Ch, 4,

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

4/29

76 Dom inium in

13th

and

14th Century Political

Thought

II

Jean Ouiddort of Paris wrote the De Potestate Regia et Papali in 1302 a

contribution to the debate between Philippe IV, the Fair , of France and P

Boniface VIII .oOstensibly the issue was to determ ine sphe res of sovereignty

the parts of secular and ecclesiastical p o w er s, and Jo hn has often been ta

to be something of a moderate because he was careful to maintain a via me

that recognized tw o pow ers but com pletely separated ecclesiastical from secu

jurisdiction, firstly with regards to the respective internal structures, secon

with regard to their respective powers over property, and thirdly, with regard

the moral influence of each power. His moderation lay in his not having cho

the road of M arsilius of Pa d ua , a few years later, for w hom th e church was o

an organ of the state where the state alone possessed real power.'-

The

sacerdotium-regnum

dis pu te ha d, in effect, been going on for cen tur

During the thirteenth century it had been brought to a head by the assertion

the relatively newly founded mendicant orders, particularly the Francisca

' J . Co lem an, 'Me dieval Discussions of Pro per ty: Ratio and Dominium according to Joh

Paris and Marsil ius of Padua' , History of Potiticai Thought, IV (1983), 20 9- 28 for a fuller an a

of the texts of John of Paris, Aegidius Romanus and the Roman law influences on the theory

practice of dominium. Th e edition of the De Potestate Regia and Papati cited in this study is

Bleienstein (ed.), in Johannes Quidort von Paris. Uber Konigliche undpapstliche Gew alt. Fr

furter Studien zur Wissenschaft von der Poiitik (Stuttgart, 1969). An earlier important study,

with a less accurate text, is Jean Leclercq, Jean de Paris et L Ecctesiologie du XIW siecte (P

Vrin, 1942).

' ' The problem of nationa l sovereignty especially in France is much m ore complicated than J

of P aris 's tract implies because there was a tendency toward s the formation of auton om ous pri

palities generally in fourteenth-century France: Aquitaine, Brittany, Flanders, etc., each sou

autonomy so that poli t ical developments in France were more than the progress of the monar

such duchies or principalities having characteristics of states in miniature. Their counts, dukes

princes were coming to look upon their lands as units of property with the interests of polit

entities in their own rights. See John Le Patourel, 'The King and the Princes in Fourteenth Cen

France', in J. R. Hale, R. Highfield, and B. Smalley (eds), Europe in the Late Middle A

(London, Faber , 1965), pp. 155-83.

'Sov ereig nty' in medieval trac ts (fourteen th century ) is expres.sed in the following way s: pote

constituend i, instituere et iudicare; auctoritas habet in tempo ralibus; positus est super gentes:

consensum electi et eiigentium et secundum hoc per consensum humanum potest desinere esse; s

isto corpore cooperatur natura disponendo et organizando; potestas jurisdictionis inforo exter

(coercive, governmental power, pertaining to a public authority, directed to the common go

dominatio de jure naturati. According to Ullmann, there is a personal and impersonal sense

which the term 'sovereignty' is used, developing from the Roman concept of Jurisdictio. Se

Cos ta , lurisdictio: Sem antica del potere politico nelta pubb licistica medioevale (Mai l

Pubblicazioni della Facolta di Giurisprudenza, Universita di Firenze, 1969). The earlier, perso

notion is equal to 'he who has the power ius dicere . Rex omne imperium habet in regno suo q

imperaior habet tn imperio {\3lh cen tury) . Th e personal side of sovereignty was amplified by He

Vll and Clement V's Pastoralis Cura, the latter using Roman law principles, canon law

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

5/29

JANE T COLEMAN 77

,

those not in the new orders of friars and not monks, argued biblically that

loculos, a

money bag, and

dominium and usus, and in particular over

dominium

over prop erty mea n? Ho w was it distinct

rtied an d p ossessionate papacy was being asked to judg e whether the most

properxyless, and furthermo re, was a voluntarily

What is the structure of John of Paris 's tract, D e Potestate regia et papali?

he 5chap ters hang together loosely, group s of chap ters having imposed upon

by which such subjects were trad itiona lly discussed. The wo rk does not

disputatio

or

whe re this was developed from que stions taken from the floor,

potestas, in

lordship over

material property

is to be discussed, i.e.

dominium in rebus.

'- This

arrowed understanding

of potestas

is one of the mo st significant co ntrib utio ns

o our conception of the theme of dominium in fourteenth-ce ntury texts.

However, John's most unusual and influential statements on potestas as

ominium in rebus, found in chapters 6 and 7, those to which his argument

leads and on which its development hinges, are lifted virtually word for word

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

6/29

78

Dom inium in13th and14th Century Political Thought

from someone else.

John of Paris begins as would a true Dominican and disciple of Thom

Aquinas, by displaying a sophisticated and subtle, if eclectic, understanding

Aristotle's

Politics:

it is necessary and advantageous for man to live in soc

such as a city or kingdom which is self-sufficient in everything that pertains

the whole of life and under the government of one who rules for the comm

good. Implicitly he rejects the polity and the mixed constitution in favour of

one truly superior man of books seven and eight of Aristotle's Politics who

called monarch or king. It is also clear, he says, that this kind of governme

derives from natural law in that man is naturally a civil or political and soc

animal, and the kind of government we have been discussing, he says, com

from natural law and the law of nations.''' There is, of course, also a sup

natural end of man and rulership here belongs to Jesus. Thus far, we have

parallel between the human king and Jesus the king for the parallel realms

nature and supernature. The pope is nowhere, as yet. It was necessary, becau

of mankind's original sin against God, to establish certain remedies throu

which Christ's sacrifice could benefit man, and thus the church's sacramen

were instituted and the minister as an intermediary between God and man.

In chapter 3 he compares the structure of the church and that of the secu

realm. He argues, in sum, that man is instinctively and naturally a creature w

lives in society and this instinct can lead him, depending on contingencies,

The arrangement

of the

25

chapters.

Parti

1.

The nature and the origin of royal, civil government.

2. The nature and origin of the priesthood.

3. Com parison between thestruc tureo f the hierarchy in the church and the structure of the st

ecclesiastical ministers are ordered to one head (Pyramid); the various states, however, do

need such a hierarchical ordering to one single, universal m onarch.

4.

Compares kingship and the priesthood (no true priesthood until Christ comes as mediator

to which comes first, historically. Kingship is first.

5.

Which comes first in dignity?

6. Which is first in causality; the priesthood is not first. Discussion of the kinds of power

pope has over church property.

7.

The power of the papacy in the sphere of property-ownership, over layman's property.

papacy has no

dominium

over their property.

8. Nor has the papacy jurisdiction over lay property. Christ had none.

9. Opposing arguments that Christ did have jurisdiction over lay property and replies.

10.

Christ had ojurisdiction and did not transmit the power or capacity of proprietary owners

Objections and replies.

Part//(Leclercq division of thetext).Discussion of adversaries' arguments: chapters

11-13,

of Paris's solutions (especially chapters 12-15). The six powers in the sense of capacities, of

priesthood and the rights they confer in the sphere of temporal jurisdiction. Chapters 14

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

7/29

JANET COLEMAN 79

n an exemplary way. What is also important here is John's

e a universal unifier, i.e. an emperor; it is a general argument justifying the

Next he argues that men are distinct from one another regarding their bodies,

ically distinct.^ This may well be a view influenced by the current

ses, it has other significant consequences. He says secular powers are

se because of the diversity of climates and differing physical constitutions

f men: one man cannot possibly rule the world's

temporalia

because his

the universal language of spirituality, the pope's word is universal.'' In this

s own property as it was acquired through his own industry; thus there is no

temporalia in common for each man is his own

John means that there is an apportionment of things to individuals prior

He goes on to argue that although it is true that faith requires one

ter, all the faithful need not be united in one/?o////cfl/community.

ey are united in one religious community of the faithful but not in one

'* Bleienstein (ed,),pp, 81-2 ,

Walter Ullman n, Principles of Government

and

Politics in

the

Middle Ages,

2nd ed,

(London ,

1966) an d/ I

History of Political Thought

in the

Middle Ages Havmondsv/orih,

Penguin,

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

8/29

80 Dom inium in I3th and Uth-Century

olitical

Thought

political grouping. It

is

significant that he describes the heads of communiti

whether one or diverseas arbiters. The parallel hereisthat just as the fait

an arbiter so does the state: the king or political ruler of whatever constitu

acts as arbiter, adjudicating in matters of private property, just as the p

adjudicates in m atters of orthodox faith and heresy. He says there are diffe

ways of life, and constitutions are adapted to different climates, langua

conditions of people. Thus the philosopher Aristotle shows that indivi

states are natural, but not that of an empire or one-man universal rule.

ln chapters 4 and he shows in what ways the power of the state and th

the church are related: the state is chronologically prior but the priestly is p

in dignity. Each power has its separate dom ain, each justifying its jurisdic

immediately from the one superior power above themGod. This is his

power schema. But when we turn to chapter 6 and his discussion of the rela

superiority of royalty in the order of causality, he says that the pope has no

potestas,

that is,

dominium

over exterior goods, i.e. property.^'' And sinc

pope is not truly dominus of exterior material goods but, rather, is

administrator and dispenser both in principle and practice, he then

whether the pope has at least the original and primary authority as superior

as one who exercises jurisdiction. This he denies as well. All of this is Ro

legal terminology: bona exteriora, dominium in rebus and jurisdictio.

argument itself is lifted, as is the major section of this chapter and chapte

from another scholastic, Godefroid of Fontaines, whose academic quodl

date from the 1290s.^5 What is interesting in the extensive use of Roman

canon law concepts is an assumption that these legal terms will be unders

by an audience for publicist polemic.

Ecclesiastical property as ecclesiastical has been given to communities

not to individual persons according to John and so regarding ecclesias

goods no single person has proprietas et dominium, proprietary rights

lordship, but only the community has these.2* A single person, not a

individual but as part and member of the community has a ius utendi,h

right of usage for his maintenance, judged according to his needs and s tatu

congregatio

or religious order is only unified by its head and principal me

and he not only has use of the community's goods but also has gen

administration and dispensation of all the goods of the community, alloca

according to proportional justice, dispensing in good faith for the com

good of the group as seems to him expedient; this is the position of the bi

2^ Ubi primo ostendetur quodmod o se habeat summ us pontifex ad bona exteriora q

dominium in rebus, et secundo, dato quod non sit verus dominus exteriorum bonorum

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

9/29

JANET COLEMAN 81

n whatever cathedral church. Since there is a general unity among all

the pope-on whom it is incumbent to care for the general

dispensator of all spiritual and

dominus lord of them, for only the

est et proprielaria illorum bonorum generaliter individual

dominium

in the goods allocated to them. In

he church community individual persons, whoever they may be, do not have

ominiutn;

principal members have only stewardship,

dispensationem habeant

except where they draw their recompense from service, and then only according

to need and status. .

Thus the pope is a steward of communal property; but kmgs are not in like

manner to be taken as mere guardians of communal property. Yet another

relationship amongst property as

dominium

ownership as possession and use,

and jurisdiction, obtains in the secular world. He returns to this later. Clergy as

clergy and monks as monks are not precluded from having

domtntum

of

exterior goods at least in common, because their vow does not incapacitate

them from holding property as it does some religious persons, i.e. Franciscans.

Since the founders of churches intended to transfer

dominium et proprtetatem

bonorum directly to the community of the church, so the community has

immediate and true

dominium

in these goods and not the pope or any inferior

prelates. Others, quite wrongly, he says, do not distinguish between the

modus

Vivendiof clergy and that of the minorites whose vow incapacitates them from

lordship over and ownership of goods, be they their own or goods held

communally. The minorites have only

ususfacti

as pope Nicholas

111)

said. He

therefore argues that the pope is only a steward of the property given to the

ecclesiastical community; he has a relationship to these things only as

administrator in the interests of the community; and if he betrays the

community's trust by not acting in good faith he must do penance by restoring

the property. Such betrayal of trust can and must lead to deposition because the

misuse is of dominium and property rights.^* Such betrayal by abbots of

monastic communities or by a bishop regarding his church also must lead to

deposition. If the pope knows of persons, be they ecclesiastical or lay, who

claim against him on the grounds of unjust dispensations or misused steward-

ship modo quo possunt et debent as they are able and indeed, must do, are

obliged to do, he cannot dejure legally, remove them or dispossess them from

what is theirs, for he has no authority from God to do so and the pope cannot

act against God's will. Deposition may be, in the first instance, an obligation,

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

10/29

82 Dom inium in I3th and 14th-centuryP olitical Thought

acknowledges to be prior chronologically to spiritual power and institutions,

acquired by the individual's skill, labour and own industry and individuals

individuals have in these things

ius et

potestatem et

verum

dominium,right

power and valid lordship.^' Each person may order his own, dispose o

administer, hold or alienate as he wills without injury to any other since he

dominus.In the lay world propertyisdistributed discretely through a process

acquisition characterized by individual labour. One acquires rights over t

goods for which one has laboured and therefore one can use or alienate suc

goods. Such goods or property acquired through individual labour have neith

interconnections with other men in society of whatever status, nor are th

mutually interordered,-^ nor is there a common head who may dispose of

administer such property since whose ever they are may arrange for his ow

property as he wishes.Neitherprince nor pope hasdominium or stewardship

the lay world,e tideoneeprincepsnee papahabetdominium vel dispensatio

in talibus. Individual property rights are inalienable. The purpose of ci

government is to preserve and protect private property. They are one's own

the social state of natu re, and property rights exist prior to government and a

natural. But sometimes the peace of everyoneisdisturbed because of suchbo

exteriora, when someone usurps what is another's and also because at tim

some men, through excessive love of their own do not communicate the

property to others or place it at the service ofthecommon need or welfare of t

community. Then a ruler or prince is established by the people who is to ta

charge of such situations actingasjudge and discerning between just and unj

and as a punisher of injustices or injuries, a measurer of the just proporti

owed by each to the common need and welfare.^' The rulerisestablished by

people to prevent the discomforts of not having an impartial arbiter wh

rightful owners' property is usurped; he also is established to enforce altruis

when some will not provide voluntarily from their wealth that which t

community needs for the survival of the whole. Some men do not obey what

according to AquinasJohn's fellow Dominican and teachera natur

instinct to help preserve the lives of others in addition to their own.

There are some extraordinarily Lockean moments here.

In chapter

John defines the distinction between dominium

an

jurisdict

jurisdiction is the right to decide what is just or unjust in matters pertaining

property . The prince hasthis power of jurisdiction although he does not himse

2 ' /Irf quod declarandum considerandum est quod exteriora bona taicorum non sunt colt

comm unitati sicut bona ecciesiastica, sed sunt a cquisita a singulis personis arte, labore vel indus

propria, et persona e singuiares, ut singulares sunt, habent in ipsis ius et potestatem et ver

dominium, et potest quilibet de suo ordinare, disponere, dispensare, retinere alienare pro lib

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

11/29

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

12/29

84

Dom inium in13th and14th Century Political Thought

deposable m onarch acting on trust to keep order but to whom neither prop

nor property rights is alienated. The

Rex Pacificus

as Ullmann presents

summary, argues that because the state is prior, and is by analogy the h

whereas the church is the mind of the body politic, a cessation of ecclesiast

jurisdiction would not entail a destruction of the state. The state is

foundation of the church's existence and therefore the church is dependen

the state , whilst the state is morally and physically self-sufficient. The au

does not then follow John of Paris's

viamedia

in establishing two indepe

powers; he is, rather, closer to Marsilius of Padua.^ ^ His view of potestasl

to two distinct jurisdictionsspiritual and temporal;potestas in the poli

world is linked directly to jurisdiction regarding property and is the concer

the monarch 'without whose laws there can be no property', but such hum

laws are not arbitrary expressions of a ruler's will but are God's will expre

through the medium of kings and they are therefore natural. Secular law

jurisdiction are the foundations of 'private' property for this author, and t

is no property unless the king safeguards it through human law. This is

argument for property as an artificial division of originally common goods

is supported by the auth or 's frequent citation of Augustine for whom the

law was a necessary, artificial and arbitrary ordering principle resulting f

man's disorderly, fallen nature. Apportionments and divisions of property

the prerogatives of the civil government according to Augustine and

author of

Rex Pacificus.

The author is, of course, at pains to show how C

declined to interfere with apportionments and divisions of property, and

he advised the apostles against the desire for temporal possessions because

leads to the ambition to be judge amongst parties contesting property righ

Like John of Paris, who argues point for point against the papal hiero

Aegidius Romanus when Aegidius compares church and state in term

priority in time and then in dignity,^^ the author of Rex Pacificusar

against Aegidius's thesis of the pope's universal property: bishops are

owners of ecclesiastical goods and estates but are onlydispensatores;havi

dominium

over ecclesiastical goods, the bishop has even less

dominium

ove

property. He has a right of administration over church property but no r

whatsoever over temporal goods. Like John , he argues for the autonom y o

French monarchy in secular matters, and by this is meant matters of pri

property and the exercise of rights in the legal sphere of inheritance

alienation. Unlike John (and Locke), the author ofRex

Pacificus

does no

private property as possible no less a right, prior to the people's consen

establish an arbiter with jurisdictio.

John of Paris's unusual and 'Lockean ideas before their time' are not un

to his

D e Potestateregia etpapali

however; they are almost word for wor

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

13/29

JANET COLEMAN 85

forma of anothe r

1

have argued elsewhere, ' the

de potestate

genre seems to have

deierminationes

section of the ma gisterial

quodlibet

by the

IV

. . the medieval writer had to spend his time in libraries. *^ So begins L asle tt 's

s and H arriso n 's The Library offohn Locke. To some extent

dominium.

on law by these theorists;' '- ' such use was freque nt, som etimes also extensive

gh labo ur: the development of the practice and the justificatory theory of

ary law in France and En gland during the thirteenth centu ry. Surely it is

y a matter of pro perty theo ry reflecting socioeconom ic pattern s of the

property theory also simultaneously reflected the control exercised on

(pace

Alan MacFarlane and his

^ ' Colem an, 'Medieval Discussions of Prop erty ' , p . 213.

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

14/29

86

Dom iniutn in13th and14th Century Political Thought

First, we shall say something about John of Paris's use of customary

then about the more general situation in thirteenth-century Europe, and la

deal with an extraordinary development in English common law whic

reflected in theory, in sta tute , in the written specific examples of change, tha

in the general verdicts handed down in specific cases in late thirteenth-cen

royal courts.

First, John's use of customary law: Leclercq in his commentary and edi

of

theDe Potestate regiaetpapaliwas

surely correct when he noted that R

law was used both by the early fourteenth-century papacy as much as

monarchs, each twisting its sense to favour their own causes.''- Amongst

services Roman law was asked to provide was the formulaic expression to fit

particular exigencies of the times. Monarchists as well as papal hieroc

quoted Roman law when they required a formula, e.g. 'what pleases the pr

is law', but French law (like English) rested on custom rather than on wri

Roman principles. Fidelity to customary law remained the sign and guaran

of royal autonomy in France. Precisely because customary law va

regionally and was imprecise on many points, new practices could be in

duced, sanctioned by later prescription. 'Pour toutes ces raisons, il etait

precieux aux yeux de Philippe le Bel et de ses ministres pour qu'ils

prefereassent le droit romain'. ** Ancestral custom s, examples of predecess

were not only manifestations of a national tradition but also were taken to

manifestations of natural law. The translation of Aristotle's

Ethics

Politics, and Aquinas's and other theologians' commentaries, provided

scholastic, formal, educated, justification of the

ius

gentium et

civiti

wher

latter was seen to be the natural, instinctive, customs of a people develo

from historical and geographical exigencies but in accord with the divine

and the divine will. Roman civil law, however, does seem to have contribu

some fundamental concepts and certainly formulaic expressions

categories, and the philosophy of the schools elaborated on them . Natural

was one ofthese.John of Paris responded as did Godefroid of Fontaines in

quodlibetal determinations, to contemporary 'questions from the floor' of

debating chamber. And it is especially clear that John of Paris's interests lay

the contingent applications of the natural law as determined by custom, and

resulting interpretations

o

positive hum an laws adjusted the laws themselve

situations of fact.

Such an attitude was becoming more and more usual throughout

thirteenth century: institutions were seen as modifiable, notions of autho

were changeable. Nature was seen to develop, to be in motion tow ards an e

its fulfilment, and so too concepts like responsible authority and

domin

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

15/29

JANE T COLHMAN 87

Natura,id est deus, was a frequent tag in the

tractatus de legibus.*^

This theore tical justification for legal change

ecting cu stom ary e volutio n is, I believe, just th is: a justification of wha t, in

We should observe what v >as happening as the focus of much medieval life

with the con com m itant growth in aggressiveness regarding lending m oney

nsh ips. L ittle notes that 'it is with the form ation of the com pan y (in Italy

essential element of the capitalist econom y mad e its ap p ea ra n ce . ' ' It took

It is a commonplace of medieval textbook history that the keystone of feudal

po rt. By the early twelfth century on the con tinen t, early thirteenth century

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

16/29

88

Dominium

in

13th

and

14th-Century Political Thou ght

countryside you adopt a single function as a means to earn your way; and

concommitant moral problem raised by the urban setting has to do with

moral probity of the urban professions. Like money, the professions of lawy

doctor, administratorthe bourgeoisie, are pursued and scorned. Satire is

of the major literary genres of this experience. If the city was the centre

increasing financial transaction it was also the butt of high-minded morali

the city's origins were traced back to Cain and it was pointed out that the ma

sin had once been pride but from the eleventh century onwards itwasjoine

avarice (Peter Damiani).'' A series of exceedingly strict monastic orders

established to serve as refuges, flights from rather than confrontations with

new moneyed economy. In an age of finance emerged the voluntary pauper

the involuntary poor became visible and an object of conscious and of

ostentatious charity. To combat the heretical groups that rejected the chur

adoption of the moneyed ways of the world, the voluntarily poor Francisc

and Dominicans emerged in the thirteenth century. The unique contribution

the friars was their involvement

in

urban society, creating new forms

religious expression for a pious laity that needed to be reassured that mak

money was a Christian activity. The early thirteenth-century discussions of

legitimacy of the activities of judges, notaries, merchants, teachers, prepa

the way for the justification of these professions by the end of the centur

The friars arrived on an already established scene of higher education in ur

centres, centring round cathedral schools, and helped to develop the univers

They became some of the major voices in scholasticism, and it is hig

significant that some of the primary issues treated by the intellectuals of th

mendicant orders included the role of private property, the just price,

nature of money, the morality of professional fees, commercial pro

business partnerships and u su ry . Private property and the moral

intellectual problem of its legitimacy had not been raised since the patri

period during the heights of the Roman empire. With Europe having develo

out of a barter/feudal economy to a moneyed/profit economy in a little ov

century, arguments were sought to justify private property for the convenie

and utility of men. And then Aristotle was also seen to justify private prop

as natural. When his

olitics

was translated

(c.

1260 it was plundered as a

for the times. Aquinas shows how Aristotle agrees that private property

necessary instrument of the good life and the ordered society.' Again, p

phrasing Little: when property changed hands not by a grant of a lord t

vassal in return for acknowledged services but for money, and where the st

of the buyer or seller was of no consequence in the transaction, then the iss

to be discussed by moralists concerned the just price, the notion of lords

dominium

the various forms ofuseof property that one might rent or lease

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

17/29

JANET COLEMAN 89

By the early fourteenth century the logical extension of the moral justifica-

Summa for confessors, called the

This an no un ced that there is a Ch ristian life for

Regula

or rule as do the

himself

the founder of the Franciscans,

all prope rty, whether it was to be held privately or com m unally,

' the merch ants ' sain t ' . ' -

have just summarized from Lester Little as the reason for

curia regis

rolls, from Glanvill to Br acto n, tha t is,

He tries to reconstruct the feudal component in the structure of English

d and did to ma ke out w hat did not need saying and wh at it was not thin ka ble

ls of Rich ard I and Jo h n . These source s reflect at least the formal framew ork

eft cop ious re cords of its litigation? His answer is that we ask the w rong ,

anac hron istic que stions of them . Early law suits did not work as m odern

the defendent, the court 's general and blanket verdict. '* As

began

its distinct genres, so too we confront the formulaic, the rule-bound

on of a cu sto m ary , feudal and rule-b oun d practice of twelfth-century

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

18/29

90 Dom inium in 3th and 14th-centuryPolitical Thought

usually recorded, not because they were not discussed but because cle

methods of recording and the formulaic relationships between vassals and

regarding land and services that they described further screened out

vidualisms. Only when a contemporary writer is discussing some gen

principle and how various law courts work and he gives some ficti

example based on something that may have happened in a real case; or whe

clerk is inexperienced and takes too copious minutes of court proceed

elaborating on the formulae, do we see by accident the facts we want. W

this formal expression in writing of the society s formulaic universalisms

produced in us is an assumption that the disputes we are observing are a

equals, about individualistic Englishmen, and their ownership of propert

rights to services. But in the twelfth-century cases the unspoken relation

behind court cases is seignorial; the underlying question has to do with en

ment: is so-and-so entitled to hold land, to expect services etc. The formu

presentation of cases does not remind us, as we need to be reminded, tha

feudal property arrangement was a contract, a relationship. And wha

particularly interesting in the apparent development of central royal gov

ment through the writ of novel disseisin for instance, and through the r

assizes in the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries, is that the lord is not m

an onlooker. His court still exists, as does the king s court, and Milsom ar

that instead of the king s court going over the lord s head jurisdictionally,

the king through royal justice was trying to do was to reinforce the fe

system and make certain that lords were not abusing their side of the fe

bargain. The bargain was not meant to be eliminated although royal justice

by accident, have this effect. The con tractual dialectic ofth feudal relation

was to be maintained into the mid-thirteenth century and the king s jus

Milsom argues, was enlisted in this conservative cause. The assize was

supposed to replace seignorial jurisdiction but provide a sanction agains

abuse. The phrase that is used of the lord is whether he has acted injuste

e

judicio regarding his vassal. In the early period, form was more significant

substance in m en s relations as they were recorded before the law and in t

of the contract that involved land and services. Through the recordsw see

see the piecemeal waning of this dialectical situation, this assumed contra

relationship, where homage is only one side of the gift-giving paternalism o

lord. What has been described is more or less the situation obtaining during

twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. By the end of the thirteenth cen

tenure in land had been drained of the mutuality, the interdependence o

feudal relationship, that had previously been kept in balance by the lord s c

and then the king s. By the end of the thirteenth century tenements and

appear to be independent properties in most regions, fixed by an exte

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

19/29

JANET COLEMAN 91

Tenures in the earlier courts were the

property rights;

court cases in the

lfth and early thirteenth centuries dealt with arra ng em ents , mutua l relation-

possession the lord mak ing his right to his due sdominium

each as independ ent prop erties, each passing from hand to hand

de

owns his land whilst the lord has only an od d kind of 'se rvi tud e' over the

jus in re aliena.

The fact of

dominium

has passed in on e

Thus the period in which Godefroid of Fontaines and John of Paris wrote

ther is ackno wledg ed, a role that is not depe ndent on the simple exchange of

ive go ods, but in add ition and that is what was lost the exchange of

ary respect, acknowledged rank ing; the feudal co ntract had been a wide,

Quia Etnptores

of 1290. In short, what

on of his lands by his tenan ts who became 'ow ne rs ' of the prop erty; b ut

ah en ator was forced out of the relationship and the grantee was substituted

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

20/29

92

Dom inium in I3th and 14th-century olitical Thought

comm on law are the result of great change in the legal framework the ch

from a feudal to a national, a common law about land. He says that in

thirteenth century freehold land became what it is to us, an object of prope

capable of passing from hand to hand rightfully or wrongfully; and the lo

rights became merely economic, a sort of 'servitude' attached to the land

irrelevant to its conveyance and, except for the rights of wardship and the

irrelevant to its devolution. As between the lord and tenant, the tenant

clearly the 'owner'.*'

This happened not only in England but also on the continent, and

analysis leads us to conclude that instead of the change occurring first in

legal framew ork, John of Paris is describing the results of changes brou

about by the success of a profit economy along the lines outlined by Li

where Europe was no longer primarily feudal. The idea of ownership had

place in a truly feudal framework, certainly not on the part of the ten

Without the reality of the feudal relationship,

seisin

became a one-s

possessio in rem

and defensible before the law. This is what John of

described, not a feudal, customary birthright but property laboured for

justly acquired.

Another way of putting this is to say, as Alan Harding has recently done,

by the end of the thirteenth century the notion of liberty had changed. It

been 'freedom from', that is, liberty was equated with immunities from fe

services. But it became 'freedom to', that is liberty to alienate, to ac

exercising positive freedoms. This liberty is not to be found in formu

universal lawbooks, Roman or canonistic, or indeed in

summas

like Bra

but in charters where 'liberty' normally appears in the sense of a privi

granted to a landowner.^^ By the end of the thirteenth century such lib

included rights of independent action; liberty was a matter of the exercis

power rather than the passive possession of status. In England, if the cur

approach to Magna Carta is accepted and we see it as 'the greatest charte

territorial immunity and communal privilege (of the barons as a class) ra

than as a bill of rights for individu als ' then a glance at mid-thirteenth-cen

plea rolls tells another story of developing individual, independent libertie

citizens. Such plea rolls show the replacement of feudal principalities

by

nat

monarchies in both France and England, an increase in royal jurisdic

whereby, as Milsom noted, individual liberties inadvertantly became ri

defended at law. Harding has argued that the crucial change from a socie

*i S. F. C. Milsom, Historical Foundations of the Com mon Law (London, But terworth ,

p . 104. This is a purely lay relationship. Barton notes that in England, ecclesiastical

succeeded in acquiring without struggle, exclusive jurisdiction over the testaments of the lait

even Glanvill speaks only of a special writ that can be used where the will and conten

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

21/29

JANET COLEMAN 93

lords and vassals to one of kings and subjects canie in the thirteenth century

with the acceptance as a proper concern of the royal courts of the whole field of

torts.*** Iron ica lly, lib erty , wh en co nside red as an aspe ct of lo rd sh ip , suffered a

decline from au to no m ou s pow er to legal right w ith th e grow th in royal justice,*-^

and this, we suggest, is what is being reflected in Godefroid of Frontaines and

John of Paris. Theirs is ultimately an argument for the growth of liberty as

freedo m to for the individu al citizen and his pro pe rty rights rathe r tha n for

the rights or liberties of monarchs.

V I

It is not surprising therefore, to find in the political thought of the nominalist

William of Ockham (who wrote polemical works in an extension of the

argum ent we confro nted in exam ining Jo hn of Paris versus Boniface VIII) what

is metaphysically, logically, linguistically and economically the contemporary

concern for the individual . As M cGrade has recently pointed o u t^ O ck ha m s

concern for the notion of

po wer/potentia

is no t simply for the politica l or

juristic na ture of powe r, but its location.* Oc kh am a nd m ost of the writers

from the later thirteenth century through the mid-fourteenth century, when

writing about power and its relation to

dominium,

wan t to define wha t sort of

entity could have pow er. O ck ha m s logical and philosophical individualism

merely serves the political individualism of so many of his less nominalist but

none the less politically and legally involved fellow polemicists.

O ck ha m s a pp roac h to the logic of langu age was an individualizing one :

universals are not real; only individuals are real. But this does not mean that

universal terms are not related to universal concepts and classes of being which

serve as mental counters. Rather, his individualizing approach to propositions

with general terms in them had a political ramification of great significance,

especially in the field of property and

dominium.

Oc kham as a suppo rter of the

Franciscan O rd er s in terpretation of its relation to prope rty and dominium

would want to un dersta nd the general prop osition all Franciscans wear grey as

equivalent to this Franciscan w ears grey and that Fran ciscan wears grey and

the o ther Franc iscan we ars grey . . . . T hu s, th e reality of th e Orde r as a

conceptual generality has not been done away with, but has nominalistically

been shown to be identified with the reality of its individual members.*^ And

this should be taken to be the logical and linguistic extension of what John of

Paris , earlier in the cen tury, depending on Godefroid of Fon taine s analysis

** Hard ing, Polit ical Liberty in the M iddle A ge s , p . 434. .

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

22/29

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

23/29

JANET COLEMAN 95

ration of the notion of rights. Tuck has argued, is the proliferation of sub-

Quia Emptores

dominium

but not

possessio

of the land.

iura to iura ad rem to dominia, came about

theorists

arguing about the naturalness or otherwise of

ow n polem ic ends ra the r tha n be cause of the need to fit a legal termin ology

dominium,

inds of relationship between man and material objects:

proprietas, possessio,

sufructus, ius utendi

and

simplex ususfacti,

he was not merely developing a

heoretical

vocabulary in 1279 to describe a systematic doctrine or theory for

he Fran cisca ns ' relation to material goo ds. He was responding to an attitude to

roperty, its varieties of ownerships and uses, that had grown up in a profit

conomy. Franciscans only wanted to claim simplex ususfacti, the power to

onsu me a com mo dity but not to trad e it, alienate it , involve it in the mo netary

world; they were thereby able to preserve themselves from the non-feudal,

profit economy and were, in effect, doing what radical but earlier monastic

groups had done: run from the current economy rather than cope with it . They

were content to be seen in the urban environment rejecting dominium an d living

like Christ.

The theoretical heart of the problem resulting from the economic realities of

late thirteenth and fourteenth-cen tury Eu rop e reflected in the com m on law, i .e.

in legal practice, and responded to by the Franciscan apostolic poverty

movement, became centred more generally on whether property was natural to

m an . Joh n of Paris and Godefroid of Fon taines, we saw, believed property was

at least prior to government, and man, labouring for his own, acted thus from

natural law. According to Ockham, a bit later, men had two kinds of

dominium, each specific, respectively, to the situation befo re an d after the

Richard Tu ck, National Rights Theories: their origin and deveiopment (Cambridge,

Cambridge University Press, 1979), p. 17.

^2 Tuck. Natural Rights Theories, p. 17. Th e 'rea lities ' of this so-called 'feu dal society were

material indeed and individually possessionate. The knight in The Dispute Between a Clerk and a

Knight (D isputatio inter clericum et militem) written in defence of Philippe IV, says he laughed on

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

24/29

96 Dom inium in

13th

and

14th-Century Political

Thought

Fall.''' Each

dominium

was possessed in common by the species and natural

Man's nature was improved after the Fall by God giving fallen men natur

common powers to appropriate temporal things as individualappropriat

and the power to set up government. This was the second kind of natu

dominium for Ockham, prior to governmentitself Other theorists argued th

civil, human law does not originate in nature but in utility. Still others d

tinguished between natural possession of the earth and its fruits and

dominiu

over it, between natural and civil rights. Others saw a natural evolution

dominium;this is clear from the texts we have examined by John of Paris a

Godefroid of Fontaines w ho, in fact, developed a labour theory of acquisitio

Aquinas had argued that natural law was neutral regarding property rights

that it did not assign specificpossessions to particular men, but there was

precept of the natural law which

forbade

private property. Rather, individ

ownership was not contrary to natura l law but was an addition to it devised

human reason.'''' Recently, Tully has argued that this view was known and us

by Locke.''- We want to go further than this and say Locke's views are closer

those of John of Paris. John of Paris, as a Dominican, is traditionally held

be a staunch defender and follower of Aquinas, but he

is

doing something m

radical than Aquinas and more akin to the Locke this author reads, at any ra

in arguing for the

positive

support of property rights from the natural law.

Recently Tierney has pointed to another fourteenth-century

Tractatus

Legibus,

possibly by Durandus de St Pourcain, which also says that individ

property rights exist in natural law.''* Durandus (?) also noted that natu

reason urged tha t, o ther things being equal, a man could claim as his own wh

he acquired by his own labour.'''' Clearly, there is more work to be done he

but

we

may summarize John of Paris and Godefroid as at least representing

aspect of the dominium theme in the early fourteenth century by saying:

them, to have property as an individual is not necessarily a feature of politi

life,

and this argument is also true of Ockham's position

pace

Tuck).' * O

again, Ockham, like John of Paris, does not try to give property rights to m

but attempts to describe the kinds of powers men have as individuals prior

government in the realm of power over discrete things, and subsequently,

analyse the role of government in preserving or augmenting such power.

In the end, men were described in fourteenth-century political theory, in le

'3 Will iam of Ockham.

Breviloquium de principatu tyrannico

(ed. R. Scholz) (Stuttg

Hiersemann, 1944/52),

111,

7 -1 1 , p p . 1 2 5 -32 ;

OpusNonagintaDierum,

Ch . 88, in

Opera Poii

II (ed. H. S. Offler and R. F. Bennett) (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1963). In his

O

Questiones, Q .ll C h.V I, Ockham says originally, God gave the world to ma nkind in comm

Deus de derit humano generi in comm uni dominium temporalium rerum \ see J. G. Sikes (e

Opera Poiitica, (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1940), p. 79, lines - 2 and p. 80,

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

25/29

JANET COLEMAN 97

in political poetry andprose, polemic and ephemera, as individuals

their lives by being in some way responsible for their material

Dominium

in a variety ofinterpretationswas taken to be the basic fact

their individualism. Tuck has pointed out that this needed only a few

to blossom forth as the classic rights theories of the seventeenth

Tierney has said more recently, even more emphatically, that the

seventeenth-century debate echoed strangely, as it were in a different

a theme that had already been clearly enunciated in western political theory

the years around 1300.^'Tully has recently made similar remarks regarding

and seventeenth-century natural law writing. We have seen that this

debate like the later one, concerned not only political authority but also

rights, dominium, sometimes understood to mean both jurisdiction

ownership, sometimes distinguishing these. After an examination of the

listing of books for Locke s library, we would suggest that the

between early fourteenth-century discussions and those of the

seventeenth century are not coincidental. ^

John of Paris was printed under his own name or read unnamed into the

*

Coleman. Medieval Readers and Uriters, Ch. 5 and conclusion.

so Tuck.

Natural Rights Theories,

pp. 28 f.

*i Tierney, Public expediency , p. 168.

Coleman, Medieval Discussions of Property , pp. 209-10. In a communication to me Mark

kind of popery from the late scholastics albeit an antipapal form of it as

John of Paris s work. See Robert Brady,An Introduction to the Old English History

4). Also now see Goldie, John Locke and Anglican Royalism ,Political Studies, XXXI (1983),

especially p. 75. .

Information on Locke s reading of Catholic authors and Catholic debates and history when in

tes, see John Lough, Locke s Reading during his stay in France

The Library, 5th series, Vlll (1953), 229-58, from which I have chosen notes of

1677, MS Locke f.2. p. 2Bishop of Worcester Stillingneet s answer to Catholiques no

(London, 1676); p. 3Stillingfleet, p. 730: Petrus Picherellus an excellent critick and

1 ,Mercure Jesuite Gene\3i, 1631), p. 850, Deposeingof

ngs ;p. 103FulgenzioMicanzio, k /wrfe/PodrePflo/o(1658), p. 55: II Cardinal di Perrone . . .

modo irritativa. (Cardinal Du Perron: in a harangue to the third estate on the occasion of the

John s support of the pope s releasing subjects from their obedience to an heretical

ing. See Harrison and Laslett, Library of John Locke, n. 1003b, p. 127 for a copy of Perroniana

Excerpta ex ore Cardinalis Perronii. . .(Geneva, 1667).] Further textual references made on

is French journey: to Bodin, Bellarmine, Inote that Bellarmine s De Romano Ponrifice \5i6).

Book V ch 1 has references to John of Paris: Locke refers to Bel larmindegrat.e t lib. arbit. Lib. I

C.14I, and to Cardinal di Perronne. 1678MS Lockef.3\ p. iiOLa corruption de TEglise Romatne

1679 MS Locke c. J3. 2f. 20: Hist, del Inquisitione, p. Fra. Paolo(Sarpi);/.22v:Catalogue de

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

26/29

98

Dom inium in 3th and I4th-CenturyPolitical Thought

seventeenth century, particularly by Calvinists and for the Gallican ca

Although the author can find no direct reference to John of Paris's

Potestate regia et papali

in Locke's listings, Locke did possess the comp

works of the conciliarist Pierre d'Ailly, in du Pin's edition of Gerson's

Op

Omnia.Pierre d'A illy's own works, in true 'scissors-and-paste' fashion, 'lif

John of Paris's Prologue and, yes, chapters 6 and 7 of the D e Potestate,

included them in his own and as his own.*' other works in Locke's library

known to mention John of Paris at least as a hero of the Gallican cause or

conciliarism, or else he is recognized as having favoured avia

media

in sup

of a separation of the two powers, church and state. It clearly would not h

been wise for the politically astu te Whig Locke to cite a Catholic and schola

in support of his own ideas on property.* As Goldie has recently argued,

Royalists accused the Whigs of popery with a true historical sense; Br

The credit for discovering d'A illy's use of Joh n of Pa ris must go to J. A lm ain . D'Ailly

ecclesiae et cardinalium auctoritate. III (Constance, 1416) transmits completely without givin

source, John of Paris 's

Ekpo testate,

chs 6 and 7. Also d 'Ailly 's prologue reproduces word for

John of P aris 's prolog ue and also parts of ch. 13. See the edit ion, E. du Pin of Ge rson 's O

Omnia, I, col. 980 and 1011; in the 1706 editio n, vo l. I. col. 91 4- 17 ; the prolog ue, col. 89

Gerson also wrote a

De jurisdictione spirituali et temp orali

now edited by G. H. M . P osthu

Meyjes (Leiden, Brill, 1978) on the respective rights and powers of the two jurisdictions wit

adopting the extreme doctrines of the papal hierocrats, and drawing upon the via media of Joh

Paris. Also see, G. H. M. Posthumus Meyjes, Jean Gerson et L Assemblee de Vincennes (1

(Leiden, Brill, 1981). In Locke's library, the du Pin edition (Nouvelles Bibliotheque de Aut

Ecclesiastiques) is no. 2306, in Harrison and Laslett (eds), p. 209.

For information on early texts used for the Gallican cause see K. Schleyer,

Anfanger

Gallikanismus im 13. Jahrhundert

(Berlin, 1937). Also see the discussion an d bibliogra ph

Francis Oakley, 'Natural Law, the Corpus Mysticum, and consent in Co nciliar Tho ugh t from J

of Paris to Matthias Ugonis ' ,

Speculum,

56 (1981), 786 -81 0. On Pierre d 'Ailly, Gerson, J

Major and Jacques Almain; their concern with jurisdiction of the church and i ts public, coerc

nonsacramental anjd poli t ical subdivision: potestas jurisdictionis inforo exteriori, pp. 795 f;

On John of Paris and the power of coercive jurisdiction in the external forum: the governme

power, pp.

799f

805. Al lof these phi losop her- theo logians , Oakley argues , 'comp rise an imp or

subgro up of conciliar thinkers wh o treated the church less as a unique and m ysterious com mu nit

salvation than as one of a class of rightly ordained societies, focusing attention on ecclesiast

power under its most unambiguous political guise, by disengaging their essentially constitution

theories from the particularizing elements of ecclesiastical, national and regional law or cus

and by bringing them into connection with the more universal mandates of the natural law. T

they formulated theoretical principles underlying medieval constitutionalism that reverberate

the mid-seventeenth cen tury amon g Protestan t resistance theorists and Parliam entary o ppo nen t

Ch arles I of England durin g the first civil war .' (p. 805.) For later seventeenth-c entury 'reverb

tions ' see Henry Foulis 's tract . The History of the Wicked Plots and Conspiracies of our Preten

Saints (1662)

and the encyclopaedic

The History of Rom ish Treasons and Usurpations

(16

Oakley is correct when he says: 'a heightened interest must attach to the formulations of John

Paris, Pierre d 'Ailly, Jean Gerson, Nicholas of Cusa, Jacques Almain and John Major. Altho

by so doing they left themselves open to the charg e of having drawn their tenets not from the so

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

27/29

J A N E T C O L E M A N 99

attacked not Aquinas but the late Sorbonne philosophers, John of Paris and

Jacques Almain.**-^ Tully has cited but not fully discussed a tract by Locke 'on

civil and ecclesiastical power' dated 1673-4.** It is clear that the

de potestate

regia et papali genre was alive and well in the seventeenth century.

This is not the place to trace the history of later medieval political theories

that suited, for instance, the Gallican cause, into the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries. Kelley^' has shown how lawyers took over the ideological leadership

from late medieval theologians where lawyers were regarded, especially in

France, as champions of legitimacy and royalism but were soon drawn into the

service of the Protestant resistance and hence adapted their professional

heritage to this new cau se. Charles Du M ou lin's

Contraabususpaparum

(Paris

1609) was only one of many texts that cited John of Paris, Ockham and Gerson

to suit their positions. The Calvinist Goldast collected together most of the

relevant late medieval texts we have discussed in his

Monarchia Sancti Romani

Imperii (H ano ver and Fra nk furt, 161 1-14 ). Th e literature dealing with the

papa l schism of the late fou rteen th-fiftee nth centuries and the subsequent

conciliarist discussions used John of Paris extensively, and one might cite

Nicholas de Clamanges

[De ruina et de reparatione ecclesie

(1400)] *' who was

only one of many who used John of Paris for his own views on the origins of

ecclesiastical p rope rty. A s we have already note d, Pierre d'Ailly 's De Ecclesiae

et cardinalium autoritale. III (C ons tanc e, 1416) transm itted u nackno wledg ed

John of Paris ' chapters 6 and 7, and Cardinal T urrecre m ata, the D ominican

(d. 1468), wrote a

Summa de Ecclesia

(II c. 89) in which he absorbed John of

Paris's doctrine on lay and ecclesiastical property. This was published in

Salamanca, 1560. The Franciscan Delafino wrote a

De Ecclesia

(Venice, 1552)

where he used John of Paris 's terms regarding property. Gallican historians are

aware of these borrowings as Leclercq has shown; (one need only cite here the

works of Pierre Dupuy in Locke's library, numbers 2893-4), and the sixteenth

and seventeenth centuries saw several editions of John's

D e Polestate regia et

papali

John being considered a hero of the Sorbonne theologians and the

university of Paris tradition in the debate between Henri IV and Louis XIII.

Locke was not only acquainted with many of these tracts but more generally

with European men of letters, in France and the Netherlands. He was able to

write his

Essay concerning hum ane understanding Letters of Toleration

and

Thoughts concerning Education

when he was abroad and without his own

library to hand, and it is known that during his years in the Netherlands friends

lent him bo ok s. O ne of the great virtues of Tully 's study is his dem ons tration of

the living tradition of the question of dominium and the consequen t generation

of obligations and rights in part deriving from an understanding of God as

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

28/29

100 Dominium in

3th

and 14th century

Political

Thought

maker with a special r ight in man as His workmanship, and the analog

concept of m an as maker with rights and co rrelative duties. Lo cke s property

right in common with all of mankind is, like that of the medievals we h

discussed, a subjective right. It is only by seeing the late medieval theolog

arguments as developments of what is rightfully common to all to wha

rightfully on e s ow n, that we can un der stan d how they determ ined the limits

individual property as inclusive and exclusive, defensible in courts of law, a

with a legacy that was actively reasserted th rou gh ou t the next several centu r

Locke and his peers, as Tuck has shown, drew on a living tradition of thou

which h e, like all co ntr ibu tors to the tradit ion , turn ed to his own pu rpose s in

later seventeenth century.

-

8/10/2019 'Dominium' in Medieval Political Thought

29/29