Document of The World Bankdocuments.worldbank.org/curated/en/...DTI Department of Trade and Industry...

Transcript of Document of The World Bankdocuments.worldbank.org/curated/en/...DTI Department of Trade and Industry...

Document of The World Bank

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY

Report No. 59170-PH

INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT

PROGRAM DOCUMENT

FOR A PROPOSED

FIRST DEVELOPMENT POLICY LOAN TO FOSTER MORE INCLUSIVE GROWTH

IN THE AMOUNT OF US$250 MILLION

TO THE REPUBLIC OF PHILIPPINES

APRIL 20, 2011

Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit East Asia and Pacific Region

This document is being made publicly available prior to Board consideration. This does not imply a presumed outcome. This document may be updated following Board consideration and the updated document will be made publicly available in accordance with the Bank’s Policy on Access to Information.

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

GOVERNMENT FISCAL YEAR January 1 to December 31

CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective as of April 20, 2011)

US$1 = 43.28 PHP (Philippine Peso) PHP1 = US$0.0231

Weights and Measures

Metric System

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AusAID Australian Agency for International Development JPHRDTF Japan Policy & Human Res. Dev. Trust Fund ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations LDP Letter of Development Policy ACLC Automatic Conversion into Local Currency LGUs Local Government units BESRA Basic Education Reform Agenda LTS Large Taxpayer Services BIR Bureau of Internal Revenue MDGs Millennium Development Goals BPLS Business Permit and Licensing System MTEF Medium Term Expenditure Framework BPO Business Process Outsourcing NAT National Achievement Tests BOC Bureau of Customs NEDA National Economic and Development Authority BOSS Business One-Stop Shop NERBAC National Econ. Research & Business Action Ctre BSP Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (Central Bank) NFA National Food Authority CAS Country Assistance Strategy NG National Government CCT Conditional Cash Transfer NGICS National Guidelines on Internal Control Standards CFAA Country Financial Accountability Assessment NHIP National Health Insurance Program COA Commission on Audit NSW National Single Window DBCC Development Budget and Coordination Committee OPIF Organizational Performance Infor. Framework DBM Department of Budget and Management 4Ps Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (CCT) DepED Department of Education PBR Philippine Business Registry DILG Department of the Interior and Local Government PDAF Priority Development Assistance Fund DPL Development Policy Loan PDF Philippines Development Forum DRMO Debt and Risk Management Office PDP Philippine Development Plan DOJ Department of Justice PER Public Expenditure Review DSWD Department of Social Welfare and Development PEZA Philippine Export Zone Authority DOF Department of Finance PFM Public Financial Management DOH Department of Health PGIAM Philippines Government Internal Audit Manual DTI Department of Trade and Industry PhilHealth Philippine Health Insurance Corporation EAP East Asia and the Pacific PPPs Public-Private Partnerships EIA Environmental Impact Assessment PSALM Public Sector Asset Liability Mgmt company E2M Electronic-to Mobile Customs RATE Run After Tax Evaders ESC Education Service Contracting RATS Run After the Smuggles FIR Fiscal Incentives Rationalization RIPS Revenue Integrity Protection Service FRS Fiscal Risk Statement ROSC Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes GASTPE Govt. Assistance Students/Teachers in Priv. Education SDR Special Drawing Rights GDP Gross Domestic Product SPFs Special Purpose Funds GIFMIS Govt. Integrated Financial Mgmt. Information System SEC Securities and Exchange Commission GOCCs Government Owned and Controlled Corporations SPF State and Peace-Building Fund HIPC Heavily Indebted Poor Countries SBM School Based Management IAC Inter-Agency Committee (for COA, DBM, DOF) TTRI Trade Tariff Restrictiveness Index IAS Internal Audit Service TCCs Tax Credit Certificates IBRD International Bank for Reconstruction & Development UNDP United Nations Development Program

IFC International Finance Corporation ZBB Zero –Based Budgeting IMF International Monetary Fund

Vice President:Country Director:

Sector Director:Task Team Leader:

James W. Adams Bert Hofman Vikram Nehru Ulrich Lächler

Republic of the Philippines

First Development Policy Loan to Foster More Inclusive Growth

TABLE OF CONTENTS LOAN AND PROGRAM SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1 II. COUNTRY CONTEXT ................................................................................................................... 5

A. Recent Economic Developments in the Philippines .................................................................. 5 B. Macroeconomic Outlook and Debt Sustainability ..................................................................... 8

III. THE GOVERNMENT’S PROGRAM AND PARTICIPATORY PROCESSES ....................... 13 A. Maintaining a stable macroeconomic environment ................................................................... 14 B. Improving Competitiveness and Increasing Infrastructure Investment ..................................... 23 C. Improving Governance .............................................................................................................. 29 D. Developing the Human Capital of the Poor ............................................................................... 33 E. Implementing Effective Social Safety Nets ............................................................................... 38 F. Summary Staff Assessment of the Government Program ......................................................... 40

IV. BANK SUPPORT TO THE GOVERNMENT’S PROGRAM ..................................................... 43 A. Link to CAS............................................................................................................................... 43 B. Collaboration with the IMF and Other Development Partners .................................................. 43 C. Relationship to Other Bank Operations ..................................................................................... 44 D. Lessons Learned from Previous DPLs ...................................................................................... 45 E. Analytical Underpinnings .......................................................................................................... 46

V. THE PROPOSED OPERATION .................................................................................................... 49 A. Operation Description ............................................................................................................... 49 B. Policy Areas .............................................................................................................................. 49

VI. OPERATION IMPLEMENTATION ............................................................................................. 55 A. Poverty and Social Impacts ....................................................................................................... 55 B. Environmental Aspects .............................................................................................................. 55 C. Implementation, Monitoring and Evaluation ............................................................................. 56 D. Fiduciary Aspects ...................................................................................................................... 56 E. Disbursement and Auditing ....................................................................................................... 56 F. Risks and Risk Mitigation ......................................................................................................... 57

ANNEXES: Annex 1: LETTER OF DEVELOPMENT POLICY .......................................................... 59 Annex 2: DPL Policy Matrix .................................................................................................... 67 Annex 3: FUND RELATIONS NOTE .................................................................................... 74 Annex 4: PHILIPPINES-AT-A-GLANCE ............................................................................. 78 MAP ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. FIGURES: Figure 1. Philippines: National Government Debt Sustainability Analysis 1/ .......................... 11

TABLES: Table 1. Philippines: Selected Economic Indicators, 2003-2013 .............................................. 9 BOXES: Box 1: Poverty in the Philippines ............................................................................................... 7 Box 2: Relationship of DPL to other Bank Operations ............................................................ 44 Box 3: Proposed Prior Actions for DPL1 and Proposed Triggers for DPL2 ........................... 50 Box 4: Expected Program Outcomes and Indicators ................................................................ 52 Box 5: Application of Good Practice Principles for Conditionality ........................................ 53 This Loan was prepared by an IBRD team led by Ulrich Lächler (Lead Economist, EASPR) and consisting of Gerlin May Y Catangui (CEAPH), Soonhwa Yi (CFPIR), Michaela Weber (AFTPE), Thao Le Nguyen (CTRFC), Maribelle S. Zonaga, Josefina U. Esguerra, Annalyn Sevilla (EACPF), Lada Strelkova (EACPQ), Lynnette Dela Cruz Perez, Suhas D. Parandekar (EASHE), Eduardo P Banzon, Sarbani Chakraborty (EASHH), Alan Townsend, Aldo Baietti (EASIN), Eric Le Borgne, Karl Kendrick Tiu Chua, Sheryll P. Namingit, Rosa Alonso I Terme (EASPR), Victor Dato (EASPS), and Minneh M. Kane (LEGES). Peer reviewers are Jan Walliser (AFTP3) and Marijn Verhoeven (PRMPS). Able logistical support was provided by Mildred Gonsalvez and Nenette V. Santero (EASPR).

LOAN AND PROGRAM SUMMARY Republic of the Philippines

First Development Policy Loan to Foster More Inclusive Growth

Borrower

Republic of the Philippines

Implementing Agency

The Department of Finance is the main liaison with the World Bank on budget support operations, but policy dialogue, monitoring and evaluation of the program supported by this DPL is shared with DBM, DOH, DepEd, DTI, DILG and NEDA.

Financing Data

Single-currency, LIBOR-based, variable spread loan on level repayment terms, for a total maturity of 25.5 years, including a grace period of 10 years; US$250 million.

Operation Type

A single-tranche operation to be fully disbursed upon effectiveness; it is the first of a programmatic series of three DPLs.

Main Policy Areas

Fiscal and Public Financial Management Investment Climate Education and Health Service Delivery

Key Outcome Indicators

Higher tax revenues, lower public debt ratios and higher sovereign credit ratings, lower costs of opening a business, increased total investment spending as a share of GDP, enhanced transparency in public financial management through a unified Chart of Accounts and timely publication of budget execution data, higher school enrolment and better quality education through lower student-teacher and student-classroom ratios, and increased health service coverage for the poor.

Program Development Objective(s) and Contribution to CAS

The overall goal of this series of DPLs is to help the Philippines achieve sustained inclusive growth through (i) better fiscal management, an improved investment climate and better governance for faster growth, and (ii) investments in human capital to enable the poor to take better advantage of emerging growth opportunities.

Risks and Risk Mitigation

The main risks are fiscal (an inability to increase public revenues due to political or institutional constraints), external (downturns in the global economy, lower capital and remittance inflows and sharply higher oil prices) and catastrophic (particularly a vulnerability to typhoons). These risks are being mitigated in this operation by focusing on efforts to improve tax policy and administration, strengthen PFM and fiscal risk management, and through parallel efforts to strengthen disaster risk management.

Operation ID P118931

1

IBRD PROGRAM DOCUMENT FOR A PROPOSED FIRST DEVELOPMENT POLICY LOAN

TO FOSTER MORE INCLUSIVE GROWTH IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

I. INTRODUCTION

1. This program document describes a single-tranche development policy loan (DPL) to the Republic of the Philippines for US$250 million. It is being proposed as the first of a programmatic series of three DPLs to support the Philippines’ efforts to foster more inclusive growth by consolidating fiscal discipline, improving competitiveness, strengthening governance and promoting human capital accumulation. The need for more inclusive growth was made evident over the last decade, when the Philippines experienced a resurgence of economic growth that did not, however, translate into greater progress in poverty reduction. Recent analytical work suggests that an important obstacle to poverty reduction in these circumstances has been the country’s high degrees of inequality in the distribution of income and in the access to public social services. At the same time, shortcomings in the provision of public infrastructure and social services undermine the sustainability of growth and the Government’s ability to reduce inequality. 2. Specific measures being supported by this operation involve actions to (i) strengthen public revenue mobilization and fiscal risk management, (ii) improve the investment climate by reducing the costs of doing business and raising public investment through better PPP arrangements, (iii) promote better public financial management, budget transparency and accountability, and (iv) strengthen the access to and quality of basic education and health services. These actions represent a sub-set of a broader government reform agenda described in the 2011-2016 Philippine Development Plan (PDP). The choice of actions to be supported was determined by several criteria that included staff assessments of the relative importance of the measures proposed for achieving the development objectives and of the Government’s capacity for timely implementation, as well as the availability of Bank expertise and engagement in particular areas. Several policy areas (e.g., social protection, energy) are not supported under this operation even though they satisfy the selection criteria because they already are being adequately supported through other Bank instruments or other development partners. 3. Most of the issues being addressed in the proposed series of DPLs are not new and the previous government’s actions to address them had been supported through an earlier programmatic series of DPLs that was approved in December 2006. That series focused on the Government’s efforts to reduce the public sector deficit and debt, strengthen the investment climate and improve service delivery through increased and more effective government spending. While significant advances were made in some areas (notably the restoration of macroeconomic stability and a lowering of the public debt), progress in the implementation of actions agreed under the program was slower than anticipated.1 As a

1 See World Bank (2009), Implementation Completion and Results Report (Report No.: ICR00001112), Sept, 30.

2

result, no follow-up DPL was approved within 24 months of the first DPL and the series lapsed in December 2008. 4. The lessons derived from this earlier DPL experience have been incorporated into the design of this operation. Key problems that contributed to unsuccessful performance of the earlier operation were insufficient country ownership of the reform program, inadequate coordination with other development partners in the context of a joint policy matrix and insufficient analytical underpinnings of certain measures. The Aquino Administration campaigned on a strong platform of reforms emphasizing improvements in governance and social services for the poor, and this commitment to reforms is evident in the 2011 Budget that was presented to Congress in August 2010. Most of the actions supported by this DPL were announced in the President’s message presenting the 2011 Budget to Congress. The Aquino Administration also appears to enjoy a stronger political mandate than the previous government, which should give it greater maneuverability in the implementation of reforms. While this operation is being prepared in close coordination with other development partners (particularly AusAID and IMF), it avoids the need to manage a joint policy matrix, which posed a challenge in the previous series of DPLs. Finally, a good number of studies and analyses were concluded since 2007 – notably a Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability Report, a report on Fostering More Inclusive Growth in the Philippines, several Public Expenditure Reviews and Philippine Development Reports and the Philippines Discussion Notes: Challenges and Options for 2010 and Beyond – that provide solid analytical underpinnings for the proposed operation. 5. Although these changes in design and domestic circumstances improve the prospects for a successful operation, many risks remain. The most important risk is that public revenues may fail to increase by a significant amount, either because of political and institutional capacity constraints that prevent adequate tax reforms or because the new measures prove inadequate. This would undermine macroeconomic stability and limit the fiscal space to levels that preclude any possibility of expanding public spending in priority areas by enough to address the shortcomings in public infrastructure and social services that are needed to achieve more inclusive growth. Other important sources of risk include the country’s external vulnerability and exposure to natural disasters (particularly the Philippines’ vulnerability to typhoons). This operation seeks to mitigate political risks by focusing on measures that do not require legislative action, as well as by avoiding politically sensitive areas (such as NFA and CCT reform) that are best supported by other means. The risks posed by external vulnerabilities and limited institutional capacities are being addressed through the actions intended to strengthen fiscal risk management and improve public financial management. In parallel, the Government has been strengthening its capacity to deal with natural disasters, including disaster response strengthening measures introduced in the aftermath of Typhoons Ondoy and Pepeng in September/October 2009. Furthermore, the World Bank is preparing a Catastrophe DPL-DDO at the Government’s request to address disaster risk management issues. 6. The DPL series is an important component of the Bank lending program contemplated in the CAS under four of its five strategic objectives. These four are the objectives of maintaining a stable macro economy, improving the investment climate, improving public

3

service delivery (in health and education), as well as the cross-cutting objective of improving governance. These strategic objectives are also consistent with the Government’s new PDP. 7. Over the last year, the Philippines has enjoyed easy access to domestic and external financing on favorable terms (para. 17). The increase in foreign capital inflows has been putting upward pressure on the Peso, prompting the Government to rely increasingly on the domestic debt market to meet its financing needs. However, the Government continues to view foreign financing from the World Bank, ADB and other official lenders as an important component of its financing strategy to avoid a crowding out of the private sector in the debt market and to keep its sources of funding diversified for better risk management.2 Also, the authorities hope to continue benefiting from the knowledge transfer associated with financing from the development financing institutions in order to raise the development impact of planned public investments. To mitigate possible pressures on the exchange rate, this operation could be converted into Pesos at disbursement through an Automatic Conversion into Local Currency (ACLC) or any time thereafter (ad-hoc currency conversion) through a swap market transaction.3

2 See interview with DOF Secretary Cesar Purisima in GobalSource Monthly Report (7 January 2011). 3 Swap market transaction into Philippine Pesos vary in terms of maturity and pricing. If the loan repayment exceeds the maturity available in the swap market at the time of the transaction the Bank can offer a partial maturity conversion with the option for the client to roll it over at maturity

5

II. COUNTRY CONTEXT

8. The Philippines is an archipelago of 7,107 islands located in Southeast Asia and divided into three island groups (Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao). It has a projected population of about 94 million inhabitants4 in 2010, with a per-capita Gross National Income (Atlas method) of US$1,790 in 2009. The Philippines has strong potential for development in terms of abundant natural resources, a talented, English-speaking workforce, a dynamic private sector and an active civil society. However, overall development outcomes have fallen short of potential, as economic growth and job generation have tended to be more modest than in neighboring countries, leading many Filipinos to seek better opportunities abroad: an estimated 10 percent of the population resides abroad and is responsible for generating annual remittances equivalent to over 10 percent of the country’s GDP. Since 2001, economic growth has picked up, but this has not translated into poverty reduction. Instead, official poverty estimates indicate that the overall incidence of poverty increased between 2003 and 2006, and then remained unchanged through 2009, which suggests that the growth that has taken place has not been sufficiently inclusive. 9. Recent Political Developments. The Philippines held its first nationwide automated elections on May 10, 2010, with President Benigno S. Aquino III winning by a comfortable margin as candidate for the Liberal party on a platform focusing on anti-corruption and poverty reduction The new Administration faces significant opportunities as well as considerable challenges: an opportunity for new policy directions and new coalitions to push the development agenda forward with renewed vigor, but a need to overcome the inertial forces that slow down decisions and program implementation during transitions. Though his Administration came under fire a few months after assuming office (on matters related to social protection strategy, reproductive health, and the management of a hostage situation in Manila), President Aquino continues to maintain a high trust rating in recent surveys. His popularity carries across all geographic areas and socio-economic groupings, but is particularly high among the poorer segments of society. Meanwhile, the leadership of the Lower House of Congress is predominantly from the Liberal party, which should facilitate implementation of the reform agenda. The President also can expect considerable support in the Senate, even though it exhibits greater party fragmentation and Senators traditionally have tended to be more independent in casting their votes on specific issues. These developments suggest that the Philippine Executive may count on more legislative support for its reform initiatives during its tenure than was available to the previous administration.

A. RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS IN THE PHILIPPINES

10. After a sharp slow-down in 2009, the Philippine economy expanded vigorously in 2010, with an estimated growth rate of 7.3 percent that represents the highest annual rate in more than 30 years and puts the economy back on its pre-crisis growth trend.5 This rapid recovery is largely attributable to the rebound in global trade and increased investor and consumer confidence, which has been driving a similar growth resurgence in other East Asian countries. In addition, the economic expansion in the Philippines is reflecting temporary

4 Based on population estimates of the National Statistical Coordination Board. 5 Real GDP growth averaged 5.7 percent during 2003-07.

6

domestic stimulus policies that were held over from 2009 and election-related spending in early 2010. 11. The main sector responsible for rebounding growth in 2010 has been industrial production, especially manufacturing and construction. In services, trade, finance, private services and, to a lesser extent, the real estate sub-sectors were the top contributors to growth. Only agriculture has been lagging behind, in part on account of the negative influence of ‘el Niño’. On the demand side, private consumption remains strong as remittance inflows remain steady, while exports and investment have revived in 2010 to yield a positive impact on growth. Merchandise exports rebounded 30 percent in 2010, thanks largely to the recovery of the global electronics market. 12. The headline inflation rate has been stable since 2009, with small variations reflecting developments in fuel, food and utility prices, and well within the Central Bank’s target zone. Monetary policy remains broadly accommodative: although the BSP withdrew some of the liquidity-enhancing measures introduced in the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis, it has kept its key policy rates unchanged since August 2009. This policy has permitted bank lending to increase modestly (to an annual growth rate of almost 10 percent, or slightly below nominal GDP growth) and help close the output gap. Increases in foreign portfolio inflows in 2010 have helped strengthen the Peso, push up the stock market index and reduce interest rates. The stronger Peso has helped to contain inflation, but the associated short term capital inflows also have raised policymakers’ concerns about the rising risk of economic and financial disruptions in the event of sudden reversals. The central bank intervened successfully in late 2010, using its forward foreign exchange swap portfolio, to stem the rapid appreciation of the Peso. 13. The labor market has been recovering from the global recession, but very slowly. The unemployment rate fell from 7.6 percent in mid-2009 to 7.1 percent in October 2010, while underemployment afflicts 19.4 percent of the labor force. Both indicators are very high by regional standards. 14. The impact of the economic recovery on poverty reduction also has been weak. Successive Family Income and Expenditure Surveys indicate that the poverty incidence indicators have hardly budged since 2003: the poverty incidence among families increased from 20 percent in 2003 to 21.1 percent in 2006 and then declined slightly to 20.9 percent in 2009. In terms of incidence among population, poverty kept increasing from 24.9 percent in 2003 to 26.4 percent in 2006 and to 26.5 percent in 2009.6 This inelastic poverty response is corroborated by recent Social Weather Station surveys, which indicate that self-rated poverty only declined slightly in 2010, while self-rated hunger incidence remains at record high levels. (See Box 1 on Poverty in the Philippines.)

6 The figures on extreme poverty (i.e., subsistence incidence) exhibit a similar pattern: in terms of family (population) incidence, extreme poverty first rises from 8.2% (11.1%) in 2003 to 8.7% (11.7%) in 2006, and then declines slightly to 7.9% (10.8%) in 2009. (These figures are based on the newly defined national poverty lines posted by the National Statistical Coordination Board on 8 February 2011.)

7

Box 1: Poverty in the Philippines

Low economic growth has been a long-standing problem in the Philippines, and largely accounts for the slow progress made in poverty reduction during the 1980s and 1990s, compared to the faster growing East Asian neighbors; see Box figure. So, when economic growth finally accelerated after 2001, expectations were raised that poverty would henceforth fall at a faster pace. These hopes were dashed by the 2006 household survey, which indicated that the improved economic performance had not translated into faster poverty reduction. Rather than declining, poverty ratios increased between 2003 and 2006, and remained broadly unchanged through 2009. Various factors explain the rise in poverty: one is the limited dynamism of economic growth, coupled with high degrees of inequality. Contrary to the evolution of GDP, real household incomes have been declining since 2000, which accounts for much of the higher poverty. In addition, considerable circumstantial evidence indicates that there also has been deterioration in the distribution of income. As noted in the 2010 World Bank report on “Fostering More Inclusive Growth” in the Philippines, various factors contributed to the worsening distribution: (i) an uneven sectoral and regional distribution of growth – where the most labor intensive sector (agriculture) and poorest regions have been exhibiting the least dynamic growth and the fastest growing sectors (manufacturing) have remained extremely capital-intensive, (ii) intense demographic pressures from rapid population growth, (iii) declines in the relative price of labor and (iv) an unequal distribution of human capital and in access to social services. These factors largely follow from the poverty profile of the Philippine poor, who tend to be concentrated in rural areas and engaged in agriculture, and to have significantly less access to basic services, lower education levels and larger families than the non-poor. To render growth more inclusive, the 2010 World Bank report recommends a two-pronged strategy aimed at (i) accelerating growth in a sustained manner to create better job opportunities, and (ii) raising the ability of poor households to take better advantage of those improved opportunities. To implement the first program, the report recommends (i) raising the tax ratio to anchor macroeconomic stability, (ii) removing infrastructure bottlenecks, (iii) improving governance, and (iv) creating a better private investment climate by reducing ‘behind the border constraints’ that inhibit business development. In regard to the second prong, as greater opportunities for job creation are being generated, the report stresses the importance of enabling workers to move to the sectors and regions where the best opportunities emerge, as well as of assisting households to participate in markets through greater investment in their human capital. This last aspect require greater investment in health and education (where the Philippines ranks far below other East Asian countries) and strengthening its systems of social protection to improve the lot of the extreme poor and prevent the near poor from falling into poverty whenever adverse economic shocks take place.

Evolution of Poverty in the Philippines and Other East Asian Countries

Source: World Bank, Development Data Platform.

15. The current account of the balance of payments yielded solid surpluses of 5.5 percent of GDP in 2009 and 5.2 percent in 2010. This robust performance reflects the strong

8

contraction of imports in 2009, followed by a more modest recovery in 2010, and strong growth of goods and services exports, combined with steady remittance inflows. As a result, gross international reserves reached a record high of US$62.5 billion in December 2010, equivalent to more than 10 months’ worth of imports and to almost six times the country’s short-term external liabilities by residual maturity. Similarly, liquid reserves (as measured by the forward book of the BSP) exceeded US$17 billion in December 2010. Meanwhile, the external debt remained broadly stable at around 38 percent of GDP; see Table 1. 16. The fiscal deficit had widened significantly in 2009, as the Government implemented an expansionary fiscal policy in response to the global financial crisis. With the extension of the Economic Resiliency Plan into 2010, fiscal policy became strongly pro-cyclical and the fiscal deficit remained large at 3.7 percent of GDP (GFS definition). The increase in the fiscal deficit of the National Government by 2.2 percent of GDP between 2008 and 2010 reflects both a decline in tax revenues and increased expenditures in almost equal measure. Despite a surging economy in 2010, the tax effort remained largely unchanged from the previous year, as many of the cuts introduced in 2009 were permanent in nature and additional revenue-eroding measures were applied in 2010. Even so, the National Government debt ratio declined slightly in 2010, due to the rapid economic growth and depreciation of the Peso value of foreign debt obligations. 17. To satisfy its higher borrowing requirement, the government has benefited from easy access to domestic and external financing on favorable terms. The Philippines’ financial markets surged to record highs thanks to improving domestic fundamentals, as well as strong foreign investor interest in Asian emerging markets in general. As noted by a joint IMF-World Bank mission that visited the Philippines in late 2009, the core Philippine financial system is sound and generally resilient to a wide range of risks. Other confidence-building factors have been the improving growth prospects, stable interest rates, strong corporate earnings, and the resolution of political uncertainty. Investors have shown a strong appetite for fixed income assets and sovereign spreads have narrowed sharply.7 The Government has been taking advantage of these favorable conditions to reduce the risk profile of its debt stock by lengthening its debt maturity and raising its domestic-to-foreign debt ratio.

B. MACROECONOMIC OUTLOOK AND DEBT SUSTAINABILITY

18. Growth is projected to remain strong over the medium term, though slightly lower than in 2010, as monetary and fiscal policies are tightened to gradually wind down the stimulus package introduced earlier. Also, the rebound of exports is expected to taper off toward more modest growth rates. Domestic consumption is projected to remain firm, buoyed by the steady inflow of remittances, while total investment increases in response to rising investor confidence. In addition to benefitting from the overall surge of foreign interest in Asian emerging markets, investor confidence in the Philippines also is expected to improve with the new administration’s strong focus on tackling corruption and reducing the costs of doing business. Even though fiscal space for additional investment spending by the public sector remains limited in the short run, the Aquino government is intent on kick-starting a new wave of public-private partnership projects to fill important gaps in infrastructure. To

7 From 261 basis points in June 2010 due to concerns regarding sovereign credit in some European countries to 155 bps points in mid-November, or within 17 bps of the country’s record low of May 2007.

9

the extent that these gaps are filled, the cost of infrastructure services should gradually decline, leading to further improvements in investor confidence. Meanwhile, the balance of payments remains robust, even though the current account is projected to yield smaller surpluses in future years.

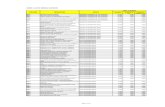

Table 1. Philippines: Selected Economic Indicators, 2003-2013 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Prel. Act.

Growth, inflation and unemployment Gross domestic product (% change) 4.9 6.4 5.0 5.3 7.1 3.7 1.1 7.3 5.0 5.4 5.5Inflation (period average) 3.5 6.0 7.6 6.2 2.8 9.3 3.2 3.8 4.8 4.5 4.5

Savings and investment Gross national savings 17.2 18.6 16.6 19.1 20.3 17.5 20.0 20.9 20.8 20.7 20.1Gross domestic investment 16.8 16.7 14.6 14.5 15.4 15.3 14.6 15.6 16.6 17.5 18.4

Public sector

National government balance (GFS basis) 1/-4.9 -4.1 -3.0 -1.4 -1.7 -1.5 -4.1 -3.7 -3.5 -2.9 -2.2

National government balance (Govt def) -4.6 -3.8 -2.7 -1.1 -0.2 -0.9 -3.9 -3.6 -3.3 -2.8 -2.1 Total revenue (Govt def) 14.8 14.5 15.0 16.2 17.1 16.2 14.6 14.4 14.6 15.3 16.0 Tax revenue 12.8 12.4 13.0 14.3 14.0 14.2 12.8 12.8 13.2 13.8 14.5 Total spending (Govt def) 19.5 18.3 17.7 17.3 17.3 17.2 18.5 18.0 18.0 18.1 18.1National government debt 77.7 78.2 71.4 63.9 55.8 57.0 57.3 56.1 53.7 51.6 48.5

Consolidated non-financial public sector debt 100.8 95.0 85.9 73.9 61.1 60.7 60.7 58.4 57.3 56.6 53.7Balance of payments

Merchandise exports (% change) 2.7 9.8 3.8 15.6 6.4 -2.5 -22.3 33.6 7.4 7.8 9.0Merchandise imports (% change) 3.1 8.0 8.0 10.9 8.7 5.6 -24.1 28.0 9.6 9.8 9.8Remittances (% change of US$ remittance) 10.1 12.8 25.0 19.4 13.2 13.7 5.6 8.2 8.5 9.0 9.0Current account balance 0.4 1.9 2.0 4.5 4.9 2.2 5.5 5.2 4.2 3.2 1.7FDI (billions of dollars) 0.2 0.1 1.7 2.8 -0.6 1.3 1.6 0.9 2.0 3.0 4.0Portfolio investment (billions of dollars) 0.6 -1.7 3.5 3.0 4.6 -3.6 0.3 0.3 3.0 3.5 3.5

International reserves

Gross official reserves 2/ (billions of dollars) 17.1 16.2 18.5 23.0 33.8 37.6 44.2 62.4 72.1 83.1 89.7Gross official reserves (months of imports) 4.0 3.6 3.8 4.2 5.8 6.0 8.7 9.6 10.2 10.7 10.2

Real Effective Exchange Rate 3/59.9 57.5 62.0 70 76.2 80.2 77.3 83.9 … … …

% change -9.9 -4.1 7.9 12.9 8.9 5.2 -3.6 8.5 … … …External debt

Total 4/ 78.6 70.1 62.4 51.3 45.8 38.9 39.0 38.1 34.9 34.4 33.3

Source: Government of the Philippines, World Bank1/ Excludes privatization receipts (treated as financing items, in accordance with GFSM) and includes CB-BOL restructuring revenues and expenditures2/ Includes gold3/ Against major trading partners (US, Japan, European Monetary Union, United Kingdom); data for 2010 is as of September; 4/ World Bank definition; The difference with central bank data is that this includes the following:

a. Gross "Due to Head Office/Branches Abroad" of branches and offshore banking units of foreign banks operating in the Philippines, which are treated as quasi-equity in view of nil and/or token amounts of permanently assigned capital required of these banksb. Long-term loans of non-banks obtained without BSP approval which cannot be serviced using foreign exchange of the Philippine banking system c. Long-term obligations under capital lease agreements

------------------------ Actual ------------------ ------ Projection ------

(in percent of GDP, unless otherwise indicated)

19. As the gap between actual and potential output is closed, the monetary authorities will be looking to gradually unwind their previous expansionary monetary policy stance. The new round of quantitative easing from certain central banks abroad may complicate these efforts, as foreign investors are eager to take advantage of yield differentials and buy up new bonds issued by the central bank (BSP). The BSP has stated its readiness to implement further prudential measures to deal with the effects of capital surges on domestic liquidity and asset price inflation.

10

20. On the fiscal front, the Aquino administration will be looking toward a gradual fiscal consolidation through higher tax revenues and improvements in the efficiency of public spending. Initial revenue measures have focused on improving tax compliance, such as the filing of a number of tax evasion cases, but these have only had a marginal impact in 2010. Revenues are projected to increase gradually after 2011, as further improvements in tax administration are implemented and other sources of leakages are plugged and tax policy measures are introduced. Meanwhile, total government spending contracted to 18 percent of GDP in 2010, thanks to initial efforts undertaken since July 2010 to review and rationalize spending by applying a zero-based budgeting (ZBB) approach. This approach also has enabled the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) to rationalize, put on hold, or scale up key programs in its draft 2011 Budget, based on efficiency and equity considerations.8 Looking ahead, DBM plans to strengthen its program evaluation capacity to make such spending reviews a regular feature of public sector expenditure programming. 21. Debt Sustainability. The balance of payments projections shown in Table 1 show a strengthening reserve position and a gradually declining external debt; from 39 percent of GDP in 2009 to 33.3 percent in 2013. Similarly, the projected trajectory of the National Government debt exhibits an even more pronounced downward trend, with the debt ratio falling from 57.3 percent of GDP in 2009 to 48.5 percent in 2013. Barring any unexpected shocks, both trajectories are indicative of a sustainable macroeconomic policy setting. This is confirmed by Figure 1, which shows a gradually declining public debt ratio in the base case projection, as well as broad resiliency to a variety of standard shocks. 22. Aside from the historical volatility exhibited by several key economic variables, the main source of fiscal risks in the Philippines is the still high level of the fiscal debt, coupled with weaknesses in the public debt management framework that prevents quick responses. Another key source of fiscal risks stems from contingent liabilities, which have been and remain large, mainly on account of the GOCCs, increased reliance on PPPs, the financial sector and threat of natural disasters. In the power sector, in particular, the Government has amassed sizeable liabilities, which projected forward will run into numerous billions of dollars over the decade or so. The Government’s Power Sector Asset-Liability Management company has been able to re-finance its debt, in part by availing itself of sovereign guarantees, but as the country approaches its foreign borrowing limit, this cannot continue indefinitely as it is likely to affect the Government’s overall credit rating. Even without considering borrowing limits, financing outcomes have not been efficient, and financing costs have been rising.

8 Rationalized programs include the Food for School Program – to be administered more efficiently by the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) using its national targeting system – and the agricultural Input Subsidies program, which was found to mainly benefit rich farmers. Several programs that exhibited weak project implementation ratings or procurement bottlenecks will have their funds held up in both 2010 and 2011, including DepEd's Textbooks, Teacher Deployment and School Building Construction, and TESDA's Training for Work Scholarship programs. Special Purpose Funds, especially the highly discretionary ones, have been trimmed down significantly. Support to government corporations that did not meet the ZBB criteria was also reduced, though measures to stop the underlying losses – mostly, but not solely, linked to quasi-fiscal operations – have yet to be announced and implemented.

11

Figure 1. Philippines: National Government Debt Sustainability Analysis 1/

53

Baseline 46

30

40

50

60

70

80

2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014

Combined shock 2/

combined shock

Source: World Bank staff calculations 1/ The shaded areas represent actual data. 2/ The ‘combined shock’ consists of permanent 1/2 standard deviation adverse shocks applied to the real interest rate, growth rate, and primary balance.

23. Key Challenges. The preceding account draws attention to the following macroeconomic challenges facing the Philippine authorities in the medium term:

Bringing down poverty is the overriding challenge: while growth is necessary, it has clearly not been enough to reduce poverty in the Philippines. In addition to implementing growth-enhancing measures, it will also be important to develop the human capital of the poor, enabling them to take better advantage of growth opportunities, while strengthening social protection mechanisms to prevent them from backsliding further into poverty as a result of adverse shocks.

Raising the tax effort: the Philippines exhibits important public expenditure gaps vis-à-vis other neighboring countries, notably in health and education, which partly explain why the Philippines has made relatively modest progress in poverty reduction since the 1980s.9 While improvements in the efficiency of public expenditures can help reduce the public spending gap, it will not be enough. Total public spending levels also will have to increase. Such an increase can only be sustained if the Government is able to reverse the erosion of tax revenues that has taken place over the last decade.

Raising and sustaining a higher-than-historical investment-to-GDP ratio: while there is a significant increase in investments this year, the challenge is sustaining a higher investment-to-GDP ratio to ensure that growth will continue in the medium/long-term.

Improving the capacity to manage fiscal risk: although the projected evolution of the fiscal deficit points in a stable direction, the weak GOCC oversight capacity of the National Government and greater prospective emphasis on PPP arrangements represent significant contingent risks that could undermine the Government’s fiscal consolidation efforts and ability to ensure a stable macroeconomic environment. In the

9 See World Bank, “Public Spending: Stepping up public spending for faster growth and poverty reduction”, Philippines Discussion Note No. 4, Report No. 55655, July 2010.

12

power sector, the challenge for the Government will be to maintain the amount of debt at a level consistent with the projected revenue available for debt service.

24. Staff Assessment. Based on the preceding considerations, the Bank task team believes that the macroeconomic framework currently in place in the Philippines is adequate for this operation. Even though the high public debt ratio continues to pose a threat to macroeconomic stability, the gradual pace of fiscal deficit and debt reduction represents a compromise between several trade-offs. In particular, the slower pace of deficit reduction contemplated in the Government’s program helps facilitate the budgetary shift toward greater social sector spending begun with the 2011 budget, instead of forcing the Government to embark on a more austere spending program that could result in spending cuts in some priority sectors. Furthermore, even though a tighter fiscal stance would help to relieve some of the pressure that is currently appreciating the Peso and impairing competitiveness, there is also the danger that such a policy adjustment would reduce growth in the short term by reducing aggregate demand.

13

III. THE GOVERNMENT’S PROGRAM AND PARTICIPATORY PROCESSES

25. At the center of the Aquino government’s development policies is a social contract with the Filipino people that envisions “a country with an organized and widely shared, rapidly expanding economy through a government dedicated to honing and mobilizing people’s skills and energies as well as the responsible harnessing of natural resources.”10 This vision of inclusive growth and poverty reduction is expected to result from a more transparent and accountable government, an uplifting and empowering of the poor and vulnerable, and faster economic growth. To render such development sustainable, the social contract also highlights the need for peace, justice, security, and preserving the integrity of natural resources.

26. The 2010-2016 Philippine Development Plan (PDP) seeks to substantiate the vision of inclusive growth and poverty reduction that underlies the social contract through concrete actions that focus on three strategic objectives: (i) attaining a sustained and high rate of economic growth that provides productive employment opportunities and reduces poverty, (ii) ensuring greater equity of access to development opportunities for all Filipinos, and (iii) implementing effective social safety nets to protect and enable those who do not have the capability to participate in the economic growth process. An overarching challenge in the pursuit of development in the Philippines is to improve governance, which has been recognized as an important constraint on sustained growth and poverty reduction.

27. To achieve the first objective of high sustained growth, the PDP focuses on maintaining a stable macroeconomic environment, improving competitiveness and increasing infrastructure investment, and improving governance, while strengthening institutions to promote competition. In order to maintain a stable macro environment, the PDP stresses the need for fiscal consolidation, low and stable inflation, a reduction in external vulnerabilities, and a strengthening of the financial system. The PDP emphasizes the development of strategic public-private partnerships (PPPs) and improvements in the investment climate for the private sector to develop public infrastructure. To improve governance, the PDP seeks to promote sound and consistent public policies, while enforcing the rule of law. It places great importance on improving the efficiency, transparency and accountability of public finances, while also raising the efficiency of public investment programming processes. It also aims to ensure equal justice for the rich and poor through reforms of the judiciary and criminal justice system, as well as to revive peace efforts in Mindanao.

28. To achieve the second objective of ensuring greater equity of access to development opportunities, the PDP focuses both on developing the human capital of the poor in order to enable them to take better advantage of emerging income-earning opportunities, and on reducing barriers to access to land, credit, technology and infrastructure services. Human capital development will be promoted through increased public investment in more and better education services, as well as on improving public health, nutrition and other basic social services.

10 Source: PDP 2010-2016, Stakeholder Consultation on the UNDP Country Programme Document, November 18, 2010

14

29. Finally, to achieve the third objective of putting in place effective social safety nets, the PDP focuses on expanding the coverage of social protection mechanisms that have proven effective and responsive, such as the conditional cash transfer program (4Ps), expanding the public health insurance program for the poor, and an improved targeting of public expenditures. Looking toward the longer term, it also emphasizes the need to strengthen disaster risk and climate change management.

30. The PDP Consultations Process. The 2011-2016 PDP was developed under the leadership of the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA), which organized several planning committees to facilitate the drafting and consultation of the document. The PDP Steering Committee was chaired by Secretary Paderanga of NEDA and included the DOF Secretary to represent the Cabinet cluster on economy, the DSWD Secretary to represent the cluster on social protection and poverty reduction, and the DILG Secretary to represent the cluster on security and governance. There were five planning committees assigned to draft the Plan chapters. National and regional consultations were conducted in December 2010/January 2011. Discussions on the Plan with development partners and other stakeholders were held on February 26, 2011, during the 2011 Philippines Development Forum. The final PDP is expected to be released in June 2011.

31. The remainder of this section focuses on four broad strategic areas of the Government’s program that are being supported by this DPL. Three of these areas, comprising the maintenance of a stable macroeconomic environment, improving competitiveness and increasing public investment, and improving governance, pursue the first objective of achieving high sustained growth. The fourth strategic area – developing the human capital of the poor – pursues the second objective of ensuring greater equity of access to development opportunities. The end of this section also provides a brief update of government efforts to implement effective social safety nets, even though it is not an area explicitly supported by this operation.

A. MAINTAINING A STABLE MACROECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT

32. An important challenge facing Philippine policymakers on the macroeconomic front is the need to gradually wind down the stimulus package implemented in 2009 and 2010 in response to the global financial crisis, without unduly restraining economic growth. With the Philippine economy’s strong growth performance in 2010, the small output gap that had opened up during the global recession is rapidly closing. The expansionary monetary and fiscal policies that were introduced during the crisis therefore need to be unwound, both to avoid overheating the economy and creating inflationary pressures, but also to create policy space for responding effectively to future shocks. To achieve this objective, the Government is taking measures to strengthen overall fiscal management, public revenue mobilization and fiscal risk management.

33. Strengthening Overall Fiscal Management. The main threats to macroeconomic instability in the Philippines over the last decade have emanated from the fiscal side, particularly a weak revenue mobilizing capacity. The PDP proposes to achieve fiscal stability and consolidation, predominantly through a marked increase in revenues, rather than through

15

expenditure compression.11 The fiscal consolidation goals are modest, as the National Government (NG) overall fiscal deficit is only projected to decline by about 2 percentage points of GDP over the six year period of this administration.12 This is enough to reduce the NG debt-to-GDP ratio by 7 percentage points of GDP to 48.8 percent of GDP by 2013, thanks to the fairly strong projected GDP growth. Although no overall expenditure compression is being planned, the Government is also intent on cutting waste and inefficient spending to help create fiscal space for priority programs that aim to fulfill the Aquino administration’s Social Contract with the Filipino people.

34. To underpin these fiscal consolidation efforts, the Executive has drafted two bills on fiscal responsibility that seek to instill fiscal discipline in the public sector by establishing principles of responsible financial management and promoting full transparency and accountability in government revenue, expenditure and borrowing programs. One version of the bill, “the short version,” establishes deficit-neutral rules when enacting new spending or tax measures. It was filed in both houses of Congress in September 2010 and is currently on second reading in the Senate.13 Key provisions of this bill are (i) the introduction of countervailing measures that offset any mandatory spending or tax legislation that increase the deficit or reduce revenues, (ii) the control of fiscal incentives by requiring all such bills to be accompanied by a certification from the Department of Finance that the incentive bill complies with the annual fiscal targets, (iii) the review of all existing fiscal incentives laws within two years after the fiscal responsibility law comes into effect, and (iv) requiring all future bills with budgetary implication to identify supporting revenue measures.

35. The other, more comprehensive, version of the bill14 includes the same deficit-neutral rules and calls for: (i) reaching a medium-term fiscal accord between the Executive and Legislature on fiscal targets to be accomplished over a period of three years, (ii) agreement on an annual budget strategy between the Executive and Legislature on macroeconomic policies and fiscal targets to be achieved in the fiscal year, (iii) establishment of a debt cap at 40 percent of GDP for the national government and 60 percent of GDP for the non-financial public sector by 2016, and (iv) the capping of personnel expenditures at 45 percent of net current revenues starting 2014. The Department of Finance is currently focusing on passage of the short version, which stands a higher likelihood of being enacted more quickly into law than the longer version.

36. Maintaining stable prices remains the primary monetary policy objective of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). Inflation targets — set at 3 to 5 percent for 2011 through 2016 — have been effective in anchoring inflation expectations in the past. The year-to-date inflation rate of 4.1 percent falls well within the central bank’s 2010 target, as are inflation expectations for 2011. With inflation expectations in check, the BSP, which cut its policy

11 Revenue (expenditure) is projected to rise from 14.6 (18.5) percent of GDP in 2009 to 19.6 (21.6) percent of GDP in 2016. 12 The deficit reduction is targeted to be achieved by 2013. From 2013 to 2016, a constant 2 percent of GDP deficit in the NG overall fiscal balance is targeted. 13 The Senate bill was filed by Senator Drilon while the House bill was filed by Representative Abaya. Both bills were drafted by DOF. 14 This bill (filed by Senator Recto) is currently being revised following a recent discussion between DOF and DBM and will be re-filed in Congress soon after.

16

rates by 200 basis points during the global financial crisis, has not yet tightened rates; policy rates are at their historical lows, while real rates are close to zero or slightly negative.

37. Subject to its inflation targeting regime, the BSP also aims to minimize exchange rate volatility while maintaining a floating exchange rate. To ensure orderly conditions and curb excessive volatility, the BSP sporadically intervenes in the foreign exchange market. With the recent rapid appreciation of the Peso, the BSP has responded by introducing measures to facilitate capital outflows to reduce excessive short-term volatility of the exchange rate (e.g., by increasing the limit on dollar purchases from $30,000 to $60,000).

38. Strengthening Public Revenue Mobilization. Revenue mobilization has been the weakest link in previous fiscal consolidation efforts. After peaking at 17 percent of GDP in 1997, total tax revenues declined steadily in the aftermath of the East Asian Financial Crisis, falling below 13 percent in 2002 and 2003. With an overall fiscal deficit of 5.6 percent of GDP and a public sector debt-to-GDP ratio that reached 100 percent, the Philippines was at the brink of a fiscal crisis. The Government averted the crisis through a set of fiscal measures in 2005 that broadened the base of the VAT, increased the VAT rate from 10 to 12 percent, and increased the corporate income tax (CIT) rate from 32 to 35 percent. Excise taxes on alcohol and tobacco were also increased but their rates were not high enough to offset inflation. An Attrition Act was also enacted to reward and punish revenue officials for meeting or failing to meet collection targets. These reforms succeeded in partially reversing the erosion of tax collections since 1997, but their impact was short-lived as the total tax intake began to decline again after 2006 due to both policy and administrative weaknesses. Economic factors also contributed to the decline, especially the downturn in 2009, though their effect on tax revenues was fairly small. In 2009, the tax effort fell to where it had been in 2003.

39. On the policy side, major revenue eroding measures include the lack of indexation of excise taxes since 2005, the removal of the 70 percent input VAT ceiling in 2007, the fall in the CIT rate from 35 to 30 percent in 2009, the increase in the exemption thresholds for the personal income tax in 2009, and several tax incentives that were enacted through the years, the latest of which include the exemption of senior citizens from the VAT. Together, these account for more than 1 percent of GDP. On the administrative side, reforms initiated in 2006 failed to take off as the revenue agencies focused their attention to meeting short-term collection targets at the expense of enhancing long-term reform efforts.15 Moreover, strong revenue collection in 2006 had adversely affected audit effort in the revenue agencies.16

40. The Aquino administration has reinvigorated efforts to strengthen revenue mobilization, initially focusing its reform efforts on tax administration measures aimed at

15 The annual turnover of BIR commissioners between 2007 and 2010 for failing to meet the collection target is a case in point. 16 A DOF assessment suggests that the contribution of administrative effort was negative in 2006 as the revenue agencies relied mostly on windfall VAT revenues to boost collection. The BIR’s administrative efforts improved marginally in 2007 and 2008, when it raised audit revenues from PHP2.2 billion to about PHP5.5 billion. In 2009, audit collection improved to PHP17 billion as the BIR intensified its audit program further. As a result, audit revenues increased from 0.3 percent of total BIR revenues in 2006 to 0.8 percent in 2007 and 2008, and further to 2.4 percent in 2009. Clearly, the bulk of BIR’s collection comes from voluntary declarations. During the mid-90s, when tax effort was highest, audit revenues accounted for about 2 percent of total BIR collections.

17

boosting compliance as well as some tax policy measures. The rationale for this approach is to first exhaust all administrative options in raising tax revenues before increasing tax rates.17 This is grounded in the finding that leakages in the income tax and VAT systems amount to about 4 percentage points of GDP.18 The incremental gains in tax collection achieved between 2007 and 2009 suggest that more focused attention on tax administration, in particular audit and enforcement activities, can raise revenues significantly. To complement tax administration efforts, the Executive is pursuing the enactment of a fiscal responsibility bill (paras. 33-34) and a fiscal incentives rationalization bill (discussed below) to plug future leakages in tax revenues. Moreover, it has begun to raise non-tax revenues by reducing government subsidies and increasing user fees. These include raising the fares of the Light Rail Transit (LRT), Metro Rail Transit (MRT), and toll fees in some expressways. The Government also has indicated that it will consider tax policy reforms in the event that the tax administration reforms do not yield the desired effects by end-2011.

41. Key administrative measures being pursued by the new administration include (i) increasing tax collection from large taxpayers, (ii) improving performance management in the BIR, (iii) setting the groundwork for improving the VAT refund mechanism, (iv) reinvigorating the Run After Tax Evaders (RATE), Run After The Smugglers (RATS), and Revenue Integrity Protection Service (RIPS)19 programs, and (v) various improvements in customs administration. Each is discussed below.

42. To secure revenues from the country’s largest taxpayers, the Government has amended the revenue regulations governing the selection of large taxpayers by expanding the selection criteria with the goal of increasing the revenue share of the LTS from 54 percent in 2010 to 85 percent of total BIR collection over the medium-term. The new revenue regulation became effective on January 1, 2011. Apart from the standard tax and turnover threshold criteria, additional criteria for becoming classified as a large taxpayer include (i) being a publicly-listed firm, (ii) affiliation to a conglomerate or multi-national company, (iii) engagement in the banking, insurance, telecoms, utilities, petroleum, tobacco, or alcohol sectors with a market capitalization of at least PHP100 million, and (iv) having a market capitalization of at least PHP300 million independent of the sector of engagement. These additional criteria were added in response to reported large-scale tax evasion and inter-conglomerate transfer pricing practices that reduce tax liabilities by firms with these characteristics. As of January 1, 2011, about 747 more large taxpayers have been enlisted, bringing the revenue share of the LTS to an estimated 62 percent in 2011. The BIR aims to reach at least 70 percent by 2013.

43. Alongside the expansion of the LTS, the BIR is also seeking to improve the capacity of the LTS. The Government has begun to restructure the Large Taxpayer Service (LTS) under the approved LTS rationalization plan (as mandated by Executive Order No. 366). Recruitment of qualified auditors to staff the office according to the LTS rationalization plan is currently in progress. This is to be followed by capacity-building programs and the reestablishment of the LTS performance management system that had been suspended since

17 As expressed by DOF Secretary Purisima in an interview published in GlobalSource Monthly Report (7 January 2011), visible efforts to improve tax administration and to reduce wasteful public expenditures are needed first in order to “gain the moral ascendancy to ask for tax increases.” 18 See World Bank, Public Expenditure Review 2010, for details on the tax gap. 19 The RIPS program refers to an anti-corruption program for revenue agencies.

18

2006. By 2013, BIR expects to have completed a business process reengineering plan for the LTS, to enable it to further improve its capacity to cater to more large taxpayers as envisioned by the amended revenue regulation.

44. The commencement by the Government of restructuring the LTS under the approved LTS rationalization plan, approval of its Revenue Regulation No 17-2010 (dated November 16, 2010), which broadens the selection criteria for large taxpayers and addition of about 747 taxpayers to the LTS as of January 1, 2011 are a Prior Action for this DPL. This action was completed in January 2011.

45. The BIR has begun to formalize a set of agency-level key performance indicators (KPIs) to improve performance management and accountability in the bureau. In 2009, BIR developed an agency scorecard using key performance indicators and collected baseline data for a number of indicators. A similar exercise is underway to collect data for 2010. In February 2011, BIR held a high-level strategic planning workshop in which a set of KPIs that conform to good international standards of tax administration were identified. BIR intends to adopt these KPIs formally by early 2012, together with a strategic plan for 2011-2016. By then it also plans to have collected the baseline data for 2011, while 2012 outcomes data becomes available by early 2013. Successful implementation of this program is expected to increase transparency and accountability in the bureau and reduce alleged widespread corruption. (The adoption of these KPIs and strategic plan, and collection of 2011 baseline data, is a trigger for DPL2.)

46. The Government has begun to address long standing problems regarding input VAT refunds. Currently, most companies with input VAT claims are given tax credit certificates (TCCs) that can in principle be used to offset future tax liabilities. In practice, however, revenue agencies, particularly BIR, do not always honor TCCs, especially when revenue collection is running behind target. In addition, Congress does not always approve the full budget for refunds, thus preventing BIR from paying out all valid refunds. The use of TCCs also has serious negative effects on the investment climate by restricting the cash management of exporters, creating disincentives to expand business, and promoting inefficient resource allocation as exporters substitute away from taxable inputs. Furthermore, firms are dissuaded from applying for VAT input refunds through disincentives (e.g., firms applying for VAT refunds are automatically subject to a tax audit), with the result that VAT refund claims are unusually low in the Philippines.

47. In March 2011, the Development Budget and Coordination Committee (DBCC) approved in principle a plan to shift from the TCC system to a cash refund system. A number of key steps have been identified to prepare for the shift to the new system and ensure its fiscal sustainability. These include (i) the review and validation of the BIR’s VAT registration system20 in accordance with Sec. 236-G of the National Internal Revenue Code, (ii) the development of a risk-based audit system that has the benefit of reducing the time of processing refund claims, (iii) the creation of individual accounts for exporters, and electronic linkages and data sharing between BIR and BOC, to enhance audit of input VAT refund claims, (iv) drafting of a bill for the creation of special accounts and earmarking VAT

20 According to the DOF, a recent IMF technical assistance mission found that BIR would not be ready to shift to a cash refund system unless the VAT registration system has been reviewed and validated.

19

payments of exporters on their importation and local purchases of goods and services to the special accounts, and (v) issuance of a BIR regulation requiring exporters to submit monthly summaries of purchases to serve as the basis for computing the amount of input VAT to be deposited in a special account.

48. The BIR is implementing its ongoing compliance programs with more vigor. In July 2010, new management teams in BIR and BOC reinvigorated the RATE and RATS programs by filing high profile tax evasion cases against fraudulent taxpayers on a weekly basis. Between July 2010 and February 2011, a total of 30 RATE cases and 26 RATS cases have been filed, including multi-billion Peso cases against two large taxpayers. The conviction rate also improved from two convictions prior to the new management to 12 convictions as of February 2011.21 Although both BIR and BOC have not yet met their respective collection targets to date, it is expected that they will do so by April 2011, when most tax returns are filed.22 Similar progress has been made on the RIPS Program. The new administration filed four new RIPS cases between July 2010 and February 2011, and a total of 76 cases are pending before the Ombudsman. In addition to 13 staff members dismissed due to graft related charges in 2009, six more were dismissed in 2010. DOF intends to continue filing one case per month, although there still have been no criminal convictions to date.

49. The main tax policy measure currently under consideration is the re-filing of the Fiscal Incentives Rationalization (FIR) Bill. Over the last decade, several bills have been filed in Congress but none has come close to ratification. One reason for this had been disagreement between the Department of Finance and the Department of Trade and Industry on salient provisions of the bill. Under the new Administration, a breakthrough was achieved when both departments agreed on key provisions of the bill. These provisions include: (i) limiting the number of incentive-granting institutions and streamlining the institutional structure in investment tax incentive policy formulation, promotion and administration, (ii) imposing sunset provisions on all incentives, (iii) domestic capture of tax payments that otherwise would have gone to other countries under various tax treaties, (iv) limiting the granting of incentives to firms under the Philippine Export Zone Authority (PEZA), (v) introducing caps on income tax holidays and tax deduction allowances, (vi) limiting income tax holidays to at most three industries and only to exports, and (vii) granting the BOC authority to inspect goods that enter and exit export processing zones. Following the agreement on these provisions, the Executive submitted the new version of the FIR bill as House Bill No. 4152 in February 2011, and the President has identified it as a priority bill in the Legislative Executive Development Advisory Council (LEDAC) meetings in early 2011. With the passage of this bill, the Government expects to generate PHP10 billion over the medium-term and, more importantly, to plug future leakages in the tax system, which according to some reports23 are costing the Government about 1 percent of GDP annually. To provide the analytical underpinnings for the bill, DOF has commenced work on measuring the tax expenditures arising from various tax incentives. The Government intends to publish a

21 A new memorandum of agreement between BIR and the Department of Justice (DOJ) has served to improve coordination between the two agencies to increase the conviction rate. 22 The vigorous implementation of the RATE Program had resulted in a 74 percent increase in personal income tax revenues from self-employed and professionals in 2005. 23 See, for instance, Reside, R. (2006), “Towards Rational Fiscal Incentives”, Economic Policy Reform Agenda Project report.

20

report on the size of fiscal incentives alongside the budget document submitted to Congress by 2013.

50. The Government’s submission of a revised Fiscal Incentives Rationalization Bill to Congress and identification as a priority bill is a Prior Action for this DPL. This action was completed in February 2011 with the filing of HB 4152 by Representatives Belmonte and Gonzalez.

51. Should tax revenues from administrative efforts and the two proposed bills prove insufficient in raising tax revenues to the desired level, the Executive would consider further tax reforms to “improve the revenue take of the tax system while promoting equity and level playing field among all stakeholders.”(See Chapter 1 of PDP). Key policy measures under consideration by DOF include raising excise tax rates and bases24 on alcohol, tobacco, and petroleum25 and indexing them to inflation, reversing several revenue-eroding measures such as VAT exemption to power transmission and senior citizens, as well as raising the VAT rate and a further broadening of the VAT base, possibly coupled with some reduction in the personal income tax rate to partially offset the increase in the tax burden.26 Related reforms in the granting of budgetary support to Government-Owned and Controlled Corporations (GOCCs), especially the National Food Authority, are also being considered to reduce the fiscal burden of subsidizing inefficient or ineffective operations of GOCCs.

52. With these reforms, the Government hopes to increase the amount of revenues generated through the LTS from 54 percent of total BIR collections in 2010 to at least 70 percent in 2013, and to raise total tax revenues in line with its PDP, from 12.8 percent of GDP in 2010 to a target level of 14.4 percent by 2013.

53. Strengthening Fiscal Risk Management. To improve the management of fiscal risks, the Government is actively pursuing a major program of institutional capacity building. An important first step for optimal management of fiscal risks is to have a timely and accurate risk assessment. This has already been achieved with the preparation of a Fiscal Risks Statement (FRS) and its publication in November 2010. The FRS contains quantitative and qualitative evaluations of fiscal risks for each of the major risk categories, as appropriate. It also includes the authorities’ ongoing efforts and plans to mitigate specific and overall risks. With the existence of the FRS – which the authorities plan to update at least annually within the context of the National Government budget submission to Congress – relative or absolute weaknesses in risk management can be better identified and prioritized. To that end, key government initiatives to structurally improve institutional capacity in managing and ultimately reducing fiscal risks focus on the public debt, PPPs, and GOCCs.

54. The publication by DBCC of a Fiscal Risks Statement as a reference for the 2011 Budget is a Prior Action for this DPL. This action was completed in November 2010.

24 The adjustment of excise tax bases is particularly relevant due to the use of fixed (1996) prices for alcohol and tobacco products that had been in production at the time of passage of the law. 25 The rates have not been adjusted since 1996. 26 See GlobalSource interview with Sec. Purisima and presentation of Undersecretary Gil Beltran in the January 31, 2011 DPL workshop.

21

55. In regard to the public debt, the Government plans to set up a Debt and Risk Management Office (DRMO) within the Department of Finance to function as a middle office enabling a more pro-active liability management, first of the National Government, and eventually of the entire non-financial public sector. It is also planning to articulate and publish a debt management strategy,27 together with key debt metrics and analyses, including a periodically updated debt sustainability analysis.

56. A strong institutional framework for project selection, approvals and contract negotiations is needed to comprehend the fiscal risks involved in PPPs.28 To date, no government unit is responsible for generating comprehensive and timely information on PPP projects. While the DOF’s review process is meant to include stress testing project parameters to determine the range of outcomes and government exposures, this is done in isolation at the individual project level without reference to the wider risk profile of public sector debt and other contingent liabilities. Moreover, because of limited manpower and technological resources, there is no system for bringing together information on PPP projects to enable adequate monitoring of risk parameters and their likely impact on the budget. Accordingly, reform efforts by DOF, DBM and NEDA aim to improve the monitoring of contingent liabilities and establish a system that will systematically estimate the extent and cost of risk exposure from PPP projects. The ICC is planning to approve and publicly disclose a PPP risk allocation matrix in order to provide clarity as to the distribution and scope of risks the National Government is exposed to. It also intends to apply a policy of publicly disclosing all signed PPP contracts.