Do Spousal Discrepancies in Marital Quality Assessments...

Transcript of Do Spousal Discrepancies in Marital Quality Assessments...

DEBORAH CARR Rutgers University

KATHRIN BOERNER Jewish Home Lifecare*

Do Spousal Discrepancies in Marital Quality

Assessments Affect Psychological

Adjustment to Widowhood?

We use prospective couple-level data fromthe Changing Lives of Older Couples toassess the extent to which spouses concur intheir assessments of marital quality (N = 844)and whether discrepancies in spouses’ mari-tal assessments affect the bereaved spouse’spsychological adjustment 6 months after loss(n = 105). Spouses’ assessments of marital qual-ity are correlated modestly (r = .45), with womenoffering less positive assessments. Bereavedpersons who had rated their marriages morepositively than their spouse at the preloss inter-view reported higher levels of anger 6 monthspostloss. We conclude that persons who offermore positive appraisals of their marriages thantheir spouse may view spousal loss as a par-ticularly unjust event. We discuss implicationsfor understanding late life marriage and spousalbereavement.

Spousal loss is one of the most distressingtransitions experienced by older adults, yet itspsychological consequences vary widely on the

Rutgers University, 30 College Avenue, New Brunswick,NJ 08901 ([email protected]).

*Jewish Home Lifecare, 120 West 106th Street, New York,NY 10025.

Key Words: death, dyadic/couple data, dying, grieving,relationship quality, widowhood.

basis of characteristics of the decedent, thebereaved, and the marital relationship (Carret al., 2000). Recent studies reveal that olderadults who rated their marriages very favor-ably experience elevated levels of yearningfollowing spousal loss, compared to personswho had less satisfying marriages (Carr et al.;Wheaton, 1990). Husbands and wives, however,may experience marriage very differently andmay not necessarily concur when assessing theemotional climate of their relationship. Discrep-ancies in spouses’ marital quality assessmentsare associated with high distress and low satis-faction among married couples (Liang, Krause,& Bennett, 2001), yet we know of no studiesthat explore whether these consequences persistafter the marriage ends and affect the adjustmentof bereaved spouses.

Our study aims to address this gap. We(a) assess the prevalence and nature of discrepantmarital quality assessments among older marriedmen and women, (b) identify the psychosocialcorrelates of such discrepant assessments, and(c) examine whether discrepant marital qualityassessments affect grief symptoms amongrecently bereaved spouses. We use data from theChanging Lives of Older Couples (CLOC) study,which obtained marital quality assessments fromhusbands and wives and tracked the bereavementexperience of those spouses who becamewidowed. The CLOC study’s prospective designand measures of both spouses’ perspectives

Journal of Marriage and Family 71 (August 2009): 495 – 509 495

496 Journal of Marriage and Family

provide us with a unique opportunity to explorewhether and how imbalances in spouses’ maritalappraisals affect the well-being of older adultswhen the marriage ends.

BACKGROUND

The physical and mental health benefits ofmarriage are documented persuasively (Mancini& Bonanno, 2006). The protective effects ofmarriage are due, in part, to the exchangeof instrumental support and emotional inti-macy. Core components of emotional inti-macy include mutuality (Kenny & Acitelli,1994), reciprocity of understanding, and sim-ilarity of spouses’ experiences, values, andattitudes (Byrne & Blaylock, 1963). Similar-ity is particularly important in long-term mar-riages; changes that create new dissimilaritiesbetween partners can cause unexpected neg-ative emotional responses (Heller & Wood,1998).

The assumption that similarity in spouses’perceptions is a prerequisite for a successfulmarriage has its roots in the symbolic interac-tionist paradigm. This sociological perspectiveis based on the assumption that rewarding socialinteractions can develop only if both partiesadhere to (or, at the very least, do not contest)a shared system of language and understanding(Blumer, 1969). Social constructionist perspec-tives emphasize that ‘‘consensus’’ and ‘‘sharedmeaning’’ are defining features of high-qualityrelationships (Berger & Kellner, 1964).

Empirical studies concur that similarity inspousal perceptions is critical for effectivefamily functioning. Discrepancies in spouses’self-reported attitudes, values, and appraisalsare associated with compromised maritalfunctioning and psychological well-being (Deal,Wampler, & Halverson, 1992; Heller & Wood,1998; Liang et al., 2001). We know of no studies,however, that have extended this line of inquiryto bereavement research. Do the psychologicallydistressing consequences of dissimilar spousalperceptions persist after the marriage ends andaffect the psychological adjustment of recentlybereaved spouses? We propose that personswhose preloss marital appraisals diverge fromthose of their spouse will grieve differently thanbereaved persons whose marital assessmentswere similar to their spouse. Further, wepropose that the psychological consequencesof discrepant assessments are contingent on

whether one offers a more or less positive maritalappraisal than their spouse. We next reviewresearch documenting the linkages betweenone’s own marital quality assessments andspousal bereavement and suggest reasons whyprior studies using the bereaved spouse’smarital assessments only provide an incompleteportrayal of one’s late marriage.

Marital Quality and Spousal Bereavement

When close emotional bonds are severed throughdeath, individuals respond with intense emo-tional reactions, including depressive symptoms,anxiety (or ‘‘active distress’’), yearning, andanger (Bowlby, 1980). Grief symptoms varyin intensity, however; attachment theories pro-pose that the dissolution of emotionally sig-nificant ties elicit the strongest psychologicalreactions. Psychoanalytic theorists concur withthis claim yet argue that the loss of a con-flicted relationship—rather than a warm andloving relationship—would lead to more intenseor ‘‘pathological’’ grief (Freud, 1917/1959).Survivors who had an ambivalent relationshipwith their late spouse are believed to havedifficulty letting go, yet they also are angryat the deceased for abandoning them. Parkesand Weiss (1983) found that widow(er)s whoreported retrospectively high levels of mari-tal conflict evidenced higher levels of anxiety,guilt, and depressive symptoms 24 to 48 monthspostloss, compared to those in less conflictedmarriages.

Two important methodological issues under-mine Parkes and Weiss’s (1983) conclusion,however. First, the bereaved provided retro-spective assessments of marital quality aftertheir spouse died, so their reports may bebiased by their current mood (Futterman, Gal-lagher, Thompson, Lovett, & Gilewski, 1990;Hirschfield et al., 1989). Second, marital qual-ity was assessed by the bereaved spouse onlyand provide only a partial assessment of themarriage.

Widowed persons may ‘‘sanctify’’ or offerunrealistically positive assessments of theirlate spouse as a way to honor the deceased(Lopata, 1981). Conversely, those who are mostdepressed postloss may offer the most negativeor ambivalent retrospective accounts of theirmarriage because depressed mood affects one’scognitions and appraisals (Beck, 1967). TheCLOC obtained marital quality measures prior

Marital Quality Discrepancies and Bereavement 497

to spousal loss, so we can examine prospectivelythe effects of marital quality and spousaldiscrepancies on the survivor’s adjustment toloss.

We know of only three studies that explorelinkages between preloss marital quality assess-ments and widow(er)s’ adjustment. Persons withbetter marriages were found to suffer moreyearning and depressive symptoms, whereasthose in conflicted marriages experience less dis-tress postloss (Bonanno et al., 2002; Carr et al.,2000; Wheaton, 1990). These findings are con-sistent with propositions of attachment theory,where the loss of close relationships is distress-ing (Bowlby, 1980). Yet these studies share animportant limitation: They focus solely on mari-tal appraisals offered by the spouse who becomesbereaved (Bonanno et al.; Carr et al.). They didnot consider whether the other spouse sharedthese assessments nor whether discrepancies inthe spouses’ perceptions shape psychologicaladjustment to loss.

The Impact of Discrepant MaritalAssessments on Spousal Bereavement

Given the persuasive literature showing that lackof consensus in marriage is associated withpoorer relationship quality and psychologicalwell-being (Deal et al., 1992; Heller &Wood, 1998), we expect that individuals whooffer marital assessments that diverge fromthose of their spouse will differ from thoseoffering concordant assessments with respectto symptoms of depression, anxiety, anger,and yearning 6 months after loss. We proposefurther that the psychological consequences ofdiscrepant assessments will vary on the basisof whether one offers a more or less positiveassessment than one’s spouse.

First, we expect that those who rate theirmarriage more positively than their spouse doeswill report fewer grief symptoms. Persons whosee their relationship and loved one in an overlypositive light report greater satisfaction withboth their marriages and their lives (Gagne& Lydon, 2004). Highly positive assessments,referred to as ‘‘optimistic illusions’’ (Taylor& Brown, 1994) or ‘‘distortions,’’ provide afeeling of emotional security that serves as acoping resource in the face of a stressor, suchas widowhood. Our study, like prior studies of‘‘distortions’’ in marital assessments, relies on asubjective indicator of discrepancy. We cannot

ascertain the veridical quality of one’s marriage,as the CLOC did not obtain marital assessmentsfrom an unbiased observer. Rather, we relyon the ‘‘constructivist approach’’ (Kruglanski,1989), where an appraisal is considered accurateif the spouses concur (Murray & Holmes, 1997).

We also expect that persons who rate themarriage more positively than their spouse willreport lower levels of yearning, relative to per-sons offering concordant assessments. Yearningreflects a desire to recover the deceased person;a highly positive view of one’s marriage maydiminish the unsettling desire to reconnect withone’s late spouse or to ‘‘undo’’ any of the wrongsor hurtful exchanges that are an inevitable aspectof long-term marriages. Those who offered morefavorable marital assessments than their spousemay be particularly adept at ‘‘continuing bonds’’with the deceased—a bereavement strategy asso-ciated with positive psychological adjustment(Boelen, Stroebe, Henk, & Zjierveld, 2006).

Second, we propose that persons whoevaluate their marriage less positively than theirspouse will report more severe grief symptoms,particularly anger and depression, relative topersons offering concordant assessments. Angeris an emotional response to experiences thatviolate or challenge one’s values (de Rivera &Grinkis, 1986; Frijda, 1993). A widely held valueamong married couples—particularly those inlong marriages—is that both partners shouldlove and care for each other more or lessequally and spouses share a consistent viewof the marriage (Berger & Kellner, 1970).When this edict is violated yet cannot beremedied because one’s spouse has died, thesurvivor may experience frustration and anger.Such imbalances also may lead to depression,because of an implied lack of control in one’srelationship.

Other Influences on Marital QualityDiscrepancies and Psychological

Adjustment to Loss

Spouses’ assessments of marital quality and thesurviving spouse’s adjustment to loss may reflectcharacteristics of each individual prior to theloss. Thus, we adjust our analyses for baselinehealth and demographic and socioeconomiccharacteristics in order to account for apotentially spurious relationship between ourpurported predictor and outcome variables.

498 Journal of Marriage and Family

First, we control preloss depressive symp-toms of both spouses because one’s emotionalstate may shape both marital appraisals andthe well-being of the survivor. Depressionmay create stressful marital interactions,which in turn could lead to further depres-sive symptoms (Davila, Bradbury, Cohan, &Tochluk, 1997)—perhaps persisting throughoutthe bereavement process. Controlling for base-line mental health also helps distinguish betweenone’s affective state before the death and changethat occurred following the death (Jacobs, 1993).

Second, marital quality and psychologicaladjustment to spousal loss are linked toone’s social resources and vulnerabilities. Wecontrol for socioeconomic status (education,income, home ownership) and demographiccharacteristics (age, race, gender) at baseline.Low socioeconomic status (SES) elevates one’srisk of both mortality and spousal loss (Feinglasset al., 2007). Persons with fewer economicresources also are susceptible to more maritalstrain (Conger et al., 1990) and psychologicaldistress (Miech, Power, & Eaton, 2007). Blacksreport consistently more marital discord thanWhites (Goodwin, 2003) and, consequently, lessdistress in the face of spousal loss (Carr, 2004).Women report poorer marital quality over thelife course (Umberson, Chen, House, Hopkins,& Slaten, 1996) than men and also adjustbetter to spousal loss (Lee, DeMaris, Bavin,& Sullivan, 2001).

Finally, we control for both spouses’ physicalhealth and caregiving status at baseline. Maritalquality and psychological well-being sufferwhen one spouse is in poor health and theother has to act as caregiver (Booth & Johnson,1994). Both the person with the disablingcondition and the healthier caregiving spousemust readjust established roles and expectations(Schumacher, 1995). The onset of healthproblems and caregiving duties may affect boththe unhealthy and healthier spouses’ perceptionsof the marriage (Gordon & Perrone, 2004).Caregiving prior to spousal loss also affects thepsychological adjustment of bereaved spouses.Although studies are inconclusive, some findthat caregivers are relieved following spousalloss, whereas others find the ‘‘wear and tear’’of caregiving makes one particularly vulnerableto the strains of bereavement (for a review, seeSchulz, Boerner, & Hebert, 2008).

In sum, we evaluate (a) the extent to whichspouses converge in their marital quality

assessments, (b) the correlates of spouses’discrepant versus convergent marital appraisals,and (c) the impact of discrepant appraisals on thepsychological adjustment of the bereaved spouse6 months after loss. Specifically, we hypothesizethat (H1) discrepant marital quality assessmentssignificantly affect the psychological well-beingof bereaved spouses, net of both partners’individual appraisals; (H2) persons whosemarital assessments are more positive than theirspouse’s will report fewer grief symptoms; and(H3) persons whose marital assessments are lesspositive than their spouse’s will report moregrief symptoms 6 months postloss.

METHOD

Sample

The CLOC study is a prospective studyof a two-stage area probability sample of1,532 married individuals from the Detroitstandard metropolitan statistical area. To beeligible for the study, respondents had to beEnglish-speaking members of a married couplewhere the husband was age 65 or older. Allsample members were noninstitutionalized andcapable of participating in a 2-hour interview.Approximately 65% of persons contacted forthe initial baseline interview participated, whichis consistent with the response rate from otherDetroit-area studies.

The baseline face-to-face interviews wereconducted from June 1987 through April 1988.For 846 of the 1,532 persons interviewed atbaseline, parallel data were collected for bothself and spouse. Thus, the CLOC has self-reported data for both husband and wife for 423marital dyads. The original CLOC investigatorsrandomly selected a subset of individuals forwhom both spouses would be interviewed; thus,persons for whom we have dyadic data do notdiffer significantly from other participants in thebaseline interview.

Following the baseline interview, studyinvestigators continuously monitored spousalloss among the CLOC participants by readingdaily obituaries in three Detroit-area newspapersand by using monthly death record tapesprovided by the State of Michigan. The NationalDeath Index (NDI) was used to confirmdeaths. Of the 319 (21% of the 1,532 baselinerespondents) who lost a spouse during the studyperiod, 276 (86%) participated in at least one

Marital Quality Discrepancies and Bereavement 499

of the three follow-up interviews that wereconducted 6 (Wave 1), 18 (Wave 2), and48 months (Wave 3) after the death. The primaryreasons for nonresponse among the remaining43 bereaved persons (14%) were refusals (38%)and ill health or death at follow-up (42%).

We used two analytic samples. First, toassess the frequency and correlates of spousaldiscrepancies in marital quality assessments,we focused on the 844 individuals for whomthe CLOC obtained both husband’s and wife’sbaseline data. We omitted the two persons(i.e., one couple) for whom one spouse didnot complete the marital assessments. Second,to assess prospectively the effects of suchdiscrepant evaluations on the psychologicaladjustment of bereaved spouses, we tracked thesubsample of study participants who becamebereaved as of the 6-month follow-up interviewand for whom both spouses’ data were obtainedat baseline. At the 6-month follow-up, 250bereaved persons (35 men and 215 women)completed interviews. Of those 250, the CLOChad obtained baseline information for self andspouse on 105 bereaved older adults (29 menand 76 women). The 105 bereaved persons forwhom couple data are available are a randomsubset of all bereaved persons; thus, this analyticsubsample does not differ significantly from theoverall bereaved sample.

Measures

Marital quality assessments and discrepancyindictors. Discrepancies in spouses’ maritalquality assessments are considered as both anoutcome and a predictor of adjustment to loss.We focus on marital quality assessed at baseline.Factor analyses of nine positively and negativelyworded items yielded one factor. We also con-structed two subscales comprising positive andnegative dimensions of marital quality, yet thescale alphas and factor loadings were superiorin the single-factor model. Scale alphas for thesingle marital quality scale were .86 and .87 forthe primary respondent and spouse, respectively.

Respondents and spouses were each asked(a) how much does your spouse make you feelloved and cared for; (b) how much is your spousewilling to listen when you need to talk about yourworries and problems; (c) there are some seriousdifficulties in our marriage (reverse-coded);(d) thinking about your marriage as a whole, howoften do you feel happy about it; (e) taking all

things together, how satisfied are you with yourmarriage; (f) how often do you feel bothered orupset by your marriage (reverse-coded); (g) myspouse doesn’t treat me as well as I deserve tobe treated (reverse-coded); (h) how often wouldyou say you and your spouse typically haveunpleasant disagreements and conflict (reverse-coded); and (i) in some marriages there are timeswhen you feel very close, but other times whenyou can get more upset with that person thanwith anyone else. How much does this soundlike the relationship you have with your spouse?(reverse-coded). Respondents were asked toassess how frequent (i.e., almost always, often,sometimes, rarely, and never) or how true (i.e.,very true, somewhat true, a little true, and notat all true) each statement was in characterizingtheir marriage. Items are drawn from the DyadicAdjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976). Total scoresequal the average response across items; scalescores are standardized, and higher scores reflectbetter marital quality.

We constructed a trichotomous indicatorof discrepancy between the two spouses’appraisals. After calculating the difference bet-ween the respondent’s and spouse’s scores (i.e.,marital qualityR—marital qualitySP), we con-structed three dichotomous measures indicatingwhether their scores were the same (referencecategory); respondent (i.e., spouse who eventu-ally becomes bereaved) offered a more positiveevaluation than spouse; or respondent offered aless positive evaluation than spouse. The cut-points were roughly one half of one standarddeviation above or below the mean discrepancyvalue.

We also considered alternative cut points(one-third and two-thirds standard deviations),yet results were consistent across models assess-ing the effects of discrepancies on psychologicaldistress among the bereaved. A more fine-grained measure of both direction and size ofdiscrepancy would offer a more informativeportrayal of marital quality discrepancies andspousal adjustment to loss, yet the subsampleof bereaved persons for whom we have bothspouses’ marital assessments (n = 105) is toosmall to subdivide further.

In our multivariate analyses, we adjust for themain effects of each partner’s marital qualityassessment as well as the categorical indicatorsof the discrepancy. We use the categoricalmeasures rather than a continuous measurerepresenting the absolute difference between

500 Journal of Marriage and Family

partners’ scores because such a model wouldbe underidentified (see Hendrickx, de Graaf,Lammers, & Ultee, 1993, for a review ofmodeling discrepancy effects).

Psychological Adjustment Outcomes

We examine four outcomes: two generalmental health indicators (depressive symptomsand anxiety) and two loss-related symptoms(yearning and anger). Depressive symptoms(α = .83) were assessed with a subset of 9negative items (e.g., felt depressed, felt sad)from the 20-item Center for EpidemiologicStudies depression (CES-D) scale (Radloff,1977). Respondents indicated how often theyexperienced each symptom in the week priorto interview. Response categories were hardlyever, some of the time, or most of thetime. Anxiety (α = .86) was assessed with 10items from the Symptom Checklist 90 Revised(Derogatis & Cleary, 1977). Respondents wereasked to indicate how often they experiencedeach symptom (e.g., nervousness, feelingfearful) in the week prior to interview. Responsecategories are not at all, a little bit, moderately,quite a bit, and extremely.

Yearning (α = .75) encompasses four symp-toms experienced in the past month: longing forone’s spouse, painful waves of missing spouse,feelings of intense pain or grief, and feelings ofloneliness and missing spouse. Anger (α = .68)taps three feelings experienced in the monthprior to the interview: resentful or bitter aboutthe death, the death was unfair, and anger towardGod. Response categories are no, never; yes,but rarely; yes, sometimes; and yes, often. Itemswere drawn from widely used grief scales includ-ing the Bereavement Index (Jacobs, Kasl, & Ost-feld, 1986), Present Feelings About Loss (Singh& Raphael, 1981), and Texas Revised Inventoryof Grief (Zisook, Devaul & Click, 1982). Scoresare standardized for ease of comparison.

Potential Confounding Factors

Spouse and respondent health at baseline eachwere assessed with the question, ‘‘How wouldyou rate your health at the present time? Wouldyou say it is excellent, very good, good, fair,or poor?’’ Responses of fair or poor are codedas 1. Both spouses’ depressive symptoms andanxiety at baseline were measured the sameway as respondents’ symptoms at the 6-monthfollow-up, described above (Derogatis & Cleary,

1977; Radloff, 1977). Both spouses’ caregivingduties are indicated with a dummy variable setequal to 1 for those who provided care to theirspouse ‘‘because of a health problem.’’ We alsoconsidered alternative cut points, such as morethan 10 hours per week. The direction and signif-icance of effects were similar, so we used the lessrestrictive measure, given the low proportion ofpersons providing spousal care at baseline.

Control Variables

Control variables include age (in years), gender(1 = female), race (1 = Black), home ownershipat baseline (1 = owns home), total householdincome at baseline (natural log of income), andeducation (a continuous measure ranging from3 to 17 years of completed schooling). Each ofthese measures refers to the demographic charac-teristics of the primary respondent (i.e., bereavedspouse). We did not separately consider bothspouses’ socioeconomic characteristics becausehousehold income and home ownership reflectresources of the couple rather than an individual.Spouses also shared demographic character-istics, reflecting assortative mating processeswhere individuals marry persons of similarages, ethnic backgrounds, and educational levels(Kalmijn, 1998). Correlations between spouses’ages and education level were .55 and .60,respectively. Nearly all CLOC participants werein racially homogamous marriages.

Finally, we control for the number ofmonths elapsed between the baseline andWave 1 interviews in all models predictingpsychological adjustment. Although Wave 1interviews occurred exactly 6 months followingspousal loss, variation in the timing of spousaldeath means that the time between the baselineand Wave 1 interviews could range from6 months to 6 years, with an average durationof 38 months (SD = 18 months).

RESULTS

Bivariate Analyses

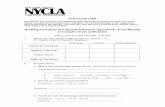

Table 1 displays means (for continuous mea-sures) or proportions (for categorical measures)for all variables used in the analysis. The leftpanel describes the large baseline sample forwhom both spouses’ assessments were obtained(N = 844). The right panel describes the subsetof individuals for whom couple-level data were

Marital Quality Discrepancies and Bereavement 501

obtained and who went on to become bereavedand participated in the 6-month follow-up inter-view (n = 105). Within each subsample, weconducted two-tailed t tests to assess significantgender differences (denoted by asterisks). Wealso conducted t tests to evaluate whetherthe bereaved subsample (n = 105) differssignificantly from the nonbereaved persons (n =739) who make up the majority of the baselinemarried sample (n = 844). Significant mean dif-ferences are denoted with the superscript a.

Spouses offered discrepant assessmentsof their marriages, with women offeringsignificantly more critical evaluations. Corre-lational analyses (not shown) conducted amongthe sample of 844 married persons revealeda zero-order correlation of just .45 betweenpartners’ marital quality reports. This mod-est correlation is surprising, given that theaverage marital duration among CLOC par-ticipants is 43 years. Women reported maritalquality scores that were roughly 0.333 SD

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for All Variables Used in Analysis

Baseline Sample of Married Bereaved Spouses at 6-MonthPersons (N = 844) Follow-Up (n = 105)

Total Men Women Total Men Women

Dependent variablesDepressive symptoms (CES-D) at 6-month follow-up

(standardized).26 .37 .22 .38 .48 .34

(1.24) (1.34) (1.21) (1.24) (1.26) (1.24)

Anxiety symptoms (standardized) .05 .12 .021 .07 .18 .026(1.07) (1.12) (1.04 (1.08) (1.27) (1.00)

Yearning (standardized) – – – .02 .15 −.024(1.03) (.99) (1.04)

Anger (standardized) – – – −.03 .33 −.17∗

(.94) (1.06) (.86)

Marital quality assessments at baselineMarital quality, own report (standardized) 0 .16 −.16∗∗∗ −.16 .026 −.175

(1.0) (.91) (1.06) (1.01) (.96) (1.03)

Marital quality, spouse report (standardized) 0 −.16 .16∗∗∗ −.03 −.173 .017(1.0) (1.06) (.92) (1.01) (.977) (1.03)

Indicators of discrepancy in spousal assessmentsRespondent higher than spouse .34 .47 .19∗∗∗ .29 .45 .22∗∗∗

Respondent and spouse: same .26 .26 .26 .27 .31 .25Respondent lower than spouse .34 .19 .47∗∗∗ .38 .17 .46∗∗∗

Potential confounds

Respondent: Depressive symptoms (CESD) atbaseline (standardized)

−.01 −.09 .07∗∗ −.03 −.22 .04

(.99) (.98) (.99) (.87) (.61) (.94)

Respondent: Anxiety at baseline (standardized) −.07 −.10 −.04 −.10 −.26 −.03+(.89) (1.07) (.66) (.59) (.47) (.61)

Spouse: Depressive symptoms (CESD) at baseline(standardized)a

0 .088 −.088∗ .20 .29 .16

(1.00) (1.00) (.99) (1.03) (1.04) (1.03)

Own health at baseline (1 = poor) .24 25 .23 .31 .24Spouse’s health at baseline (1 = poor)a .30 .28 .32 .48 .55Respondent provided care to spouse in 6 months prior

to baseline interviewa.07 .06 .08 .28 .19

Spouse provided care to respondent in 6 months priorto baseline interview

.07 .08 .06 .03 .01

Respondent became bereaved after baseline interviewa .16 .10 .22∗∗∗

502 Journal of Marriage and Family

Table 1. Continued

Baseline Sample of Married Bereaved Spouses at 6-MonthPersons (N = 844) Follow-Up (n = 105)

Total Men Women Total Men Women

Control variablesAge (in years) 69.96 72.01 67.89∗∗∗ 74.72 68.51∗∗∗

(6.09) (5.32) (6.13) (7.26) (6.20)

Gender (1 = female)a .50 – –Race (1 = Black)a .12 .12 .12 .17 .21Education (in years) 11.70 11.63 11.76 11.35 11.41

(2.86) (3.13) (2.56) (3.47) (2.71)

Income (natural log) 1.52 1.53 1.50 1.44 1.29(.48) (.50) (.49) (.50) (.48)

Home ownership (1 = owns home) .90 .90 .90 .97 .87Months between baseline and 6-month follow-up

interview– – – 38.45 37.53

(18.95) (18.31)

N 844 422 422 29 76

Notes: Data are from the Changing Lives of Older Couples Study, 1988 – 1994. Data presented are unweighted.aThe 105 persons in the baseline sample who became bereaved differ significantly from the 739 who did not lose a spouse.Two-tailed t tests were conducted to assess significant gender differences, where +p < .10. *p < .05, **p < .01,

***p < .001.

lower than those reported by men (p < .001)in the baseline sample (N = 844). A similarpattern emerged in the bereaved subsample,where women reported marital quality scoresroughly 0.2 SD lower than men, yet the gen-der difference was not significant, perhapsbecause of the reduced sample size and statisticalpower.

Persons in the baseline sample who went onto become bereaved during the study perioddiffer significantly from their nonbereavedcounterparts with respect to caregiving and bothown and spousal well-being at baseline. Personswho became bereaved during the follow-upperiod reported higher levels of depressivesymptoms at baseline, were more likely todescribe their spouse as in poor health, weremore likely to be a spousal caregiver, andwere less likely to be a spousal care recipientcompared to those who were not bereavedat the 6-month follow-up. These significantdifferences reflect the fact that older bereavedpersons typically lose their spouses to long-term chronic illness and thus may experiencespousal caregiving and emotional distress evenin the months prior to loss (Carr et al.,2001).

Multivariate Analyses

Correlates of discrepant evaluations. We usemultinomial logistic regression models toinvestigate the correlates of discrepancy inspouses’ marital assessments in the baselinesample. Odds ratios (OR) (and confidenceintervals) are presented in Table 2. Discrepantmarital quality assessments are related togender, race, depressive symptoms, and prelosscaregiving. Women are more likely than mento offer marital quality assessments that areless positive than their spouse’s (OR = 2.15,p < .001). Compared to Whites, Blacks areless likely to offer marital assessments that areconcordant with their spouse’s; they offer maritalassessments that are either less favorable (OR =2.01, p < .05) or more favorable (OR = 1.94,p < .05) than their spouse’s.

Depressed individuals and caregivers evalu-ate their marriages more negatively than theirspouses do. With each 1 SD increase in one’sown depressive symptoms, the odds that a pri-mary respondent rates his or her marriage morepoorly than one’s spouse increase by 39%, andthe odds that a spouse rates his or her mar-riage more poorly than the partner increases by46%. Primary respondents who were spousalcaregivers at baseline are roughly half has likely

Marital Quality Discrepancies and Bereavement 503

Table 2. Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting Whether Primary Respondent Assesses Marital Quality as Higher,Lower, or Same as Spouse

Marital Quality

Respondent Lower Respondent HigherThan Spouse Than Spouse

Demographic characteristicsAge (in years) .976 .995

(.93 – 1.02) (.95 – 1.04)Spouse’s age (in years) .993 .974

(.95 – 1.04) (.93 – 1.02)Gender (1 = female) 2.15** .476**

(1.31 – 3.53) (.29 – .78)Race (1 = Black) 2.01* 1.94*

(1.07 – 3.77) (1.03 – 3.65)Education (in years) 1.01 1.03

(.94 – 1.09) (.95 – 1.10)Owns home (1 = home owner) .730 .753

(.40 – 1.35) (.41 – 1.39)Income (natural log) 1.48† 1.30

(.95 – 2.29) (.84 – 2.03)Well-beingRespondent health (1 = fair/poor) .996 1.15

(.62 – 1.59) (.71 – 1.85)Spouse health (1 = fair/poor) .991 .635*

(.65 – 1.53) (.41 – .99)Respondent depressive symptoms (CES-D) 1.39** .973

(1.14 – 1.71) (.79 – 1.21)Spouse depressive symptoms (CES-D) .975 1.46***

(.79 – 1.21) (1.19 – 1.78)Respondent provided care to spouse in 6 months prior to interview .690 .481*

(.34 – 1.42) (.22 – 1.07)Spouse provided care to respondent in 6 months prior to interview .454* .662

(.21 – .99) (.33 – 1.34)Respondent became bereaved after baseline interview 1.07 1.27

(.62 – 1.84) (.73 – 2.22)Chi-square; df 155.91; 28Pseudo −R2 (Nagelkerke) .203

Notes. Data are from the Changing Lives of Older Couples Study, 1988 – 1994. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervalsare presented. The omitted category is respondent and spouse offer ‘‘same’’ assessment of marital quality.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

as noncaregivers to rate their marriages morepositively than their spouse. Similarly, spouseswho were providing direct care to the primaryrespondent at baseline are 45% as likely asnoncaregivers to rate their marriage better thantheir spouse. In sum, depressed persons andcaregivers offer more negative marital appraisalsthan their partners, with similar patterns evi-denced among both primary respondents andspouses.

In preliminary analyses, we estimated parallelordinary least squares (OLS) regression models,where the outcome was a continuous measure

of respondent’s marital quality assessment. Wefound that marital quality discrepancies arepredicted by slightly different factors than areindividual assessments. Gender, race, and bothown and spouse’s depressive symptoms weresignificant correlates of respondent’s maritalquality assessments, yet preloss caregiving wassignificantly associated with discrepant maritalassessments only.

Effect of discrepant marital assessments onbereaved spouses’ psychological adjustment.We estimated OLS regression to evaluate the

504 Journal of Marriage and Family

effects of both spouses’ marital quality assess-ments and discrepancies therein on the bereavedspouse’s psychological adjustment 6 monthsafter loss. We focused on four dimensionsof adjustment: depressive symptoms, anxiety,yearning, and anger. We found statistically sig-nificant (p < .05) effects for anger only anddiscuss only those results here. Results are pre-sented in Table 3; Model 1 includes indicators ofboth partners’ marital quality assessments anddiscrepancy indicators, Model 2 incorporates alldemographic and socioeconomic variables, andModel 3 includes baseline well-being measures.We estimated a fourth model, which adjusted forboth respondent and spousal caregiving. Neithermeasure was a significant predictor, nor did theyattenuate (or suppress) the effect of the maritalquality and discrepancy variables, so we omittedthese measures from the final analysis.

For all four outcomes, we also evaluatedmodels that adjusted for respondent and spousemarital assessments and controls only (i.e.,discrepancy measures were omitted). The modelfit was poorer than for models including thediscrepancy measures, evidenced by adjustedR2 values of .095 versus .141, in the angersymptoms model. These results suggest thatthe discrepancy measure is not capturingthe main effect of either partner’s maritalassessment (Hendrickx et al., 1993). Rather,the discrepancy indicators affect survivor well-being above and beyond the main effect ofeach partner’s assessment. We also evaluatedtwo-way interaction terms between gender andeach of the discrepancy measures; none wasstatistically significant (p < . 05).

Model 1 reveals that both spouses’ maritalquality evaluations and the discrepancy thereinaffects bereaved spouses’ anger levels 6 monthspostloss. Bereaved persons who rated their mar-riages more positively than their spouse (at base-line) have significantly higher levels of anger6 months postloss (b = .84, p < .01) comparedto those who offered marital assessments similarto those of their spouse. This effect remains largeand statistically significant (b = .72, p < .05)even when baseline characteristics are controlled(see Model 3).

Respondents’ own marital quality assess-ments also affect their anger symptomsfollowing loss. Net of all controls, Model 3shows that the more positively one appraiseshis or her marriage at baseline, the lower one’sanger levels following loss (b = −.30, p < .10).

Table 3. OLS Regression Models Estimating the Effect ofDiscrepant Marital Quality Assessments on Anger

Symptoms Among Older Bereaved Spouses 6 MonthsAfter Loss

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Marital qualityMarital quality, own −.44* −.36* −.30†

assessment (.18) (.18) (.18)

Marital quality, spouse .39* .29 .24assessment (.18) (.18) (.19)

Marital quality, own score .84** .82** .72*higher than spouse score (.32) (.32) (.33)

Marital quality, own score −.50† −.39 −.36lower than spouse score (.30) (.32) (.32)

Demographic characteristicsAge −.02 −.02

(.02) (.02)

Gender (1 = female) −.29 −.31(.24) (.24)

Race (1 = Black) −.59* −.54*(.26) (.26)

Education (in years) .007 .02(.04) (.04)

Owns home (1 = home owner) .30 .34(.31) (.31)

Income (natural log) .04 .06(.23) (.24)

Baseline well-beingOwn health (1 = fair/poor) .28

(.23)

Spouse health (1 = fair/poor) −.19(.21)

Own depressive symptoms .23*(CES-D) (.12)

Spouse’s depressive symptoms .001(CES-D) (.11)

Months between baseline and −.001Wave 1 interview (.006)

Intercept −.108 1.14 .81(.19) (1.37) (1.49)

Adjusted R2 .065 .117 .141N 105

Notes: Unstandardized regression coefficients (andstandard errors) are presented. Data are from the ChangingLives of Older Couples Study, 1988 – 1994. The omittedcategory of the discrepancy measure is ‘‘concordantassessment,’’ which includes persons whose spouse’s scorewas within to 0.50 SD of their own.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01.

These results suggest that the loss of a high-quality marriage is associated with lower levelsof postloss anger; if one’s marital assessmentdeparted substantially from their spouse’s, how-ever, anger levels are highly elevated. We found

Marital Quality Discrepancies and Bereavement 505

few other statistically significant predictors ofanger. Blacks report less anger than Whites,and persons with more depressive symptoms atbaseline report higher levels of anger symptoms6 months following loss.

DISCUSSION

Our study expands upon prior research infive ways. First, we used prospective datato examine the effects of spouses’ discrepantmarital quality assessments on the psychologicaladjustment of bereaved spouses 6 monthsafter loss. These baseline marital assessmentswere neither biased positively by retrospective‘‘sanctification’’ of the late spouse (Lopata,1981) nor biased negatively by depressedaffect experienced by the recently bereaved(Parkes & Weiss, 1983). Second, we used self-reported marital quality measures from bothpartners and evaluated the unique effects ofdiscrepant assessments on the surviving spouse’sadjustment to loss after adjusting the absolutelevel of each partner’s own assessment.

Third, because the CLOC obtained mea-sures of preloss depressive symptoms, physicalhealth, and caregiving from both spouses, wecould effectively control for potentially spuri-ous influences that may affect both the spouses’marital appraisals and the surviving spouse’spsychological adjustment 6 months postloss.Fourth, we focused on four distinctive psycho-logical symptoms following loss, so we wereable to identify specific effects that might nothave been detected in an overarching com-posite scale. Fifth, we explored whether theeffects of spousal discrepancies in marital qual-ity affect grief symptoms differently for men andwomen.

We found older husbands and wives offer dis-crepant assessments of their marriages and thatthese discrepancies have psychological conse-quences for the survivor when one’s spousedies. Moreover, discrepancies in spouses’ mar-ital assessments are related to the psychologicalstate of the persons making the assessments.We elaborate on these findings and dis-cuss their implications for understanding late-life bereavement and marital quality assess-ments.

Health Problems and Spouses’ DiscrepantMarital Appraisals

Discrepancies in spouses’ marital assessmentsare strongly related to the partners’ caregivingresponsibilities and emotional state at the time ofassessment. Persons providing care to an ailingspouse are less likely than noncaregivers to offera superior assessment of their marriage. Priorstudies have established that both the ill and thecaregiving spouse must readjust their establishedroles and interactions within the marriage(Schumacher, 1995) and these changes, in turn,affect marital appraisals (Gordon & Perrone,2004). Our results suggest further that if spouses’marital assessments change with the onset ofcaregiving duties, they may not necessarilychange in the same direction. A divergence inmarital appraisals may be a unique source ofdistress for older married couples as they grapplewith changes in daily life, including healthchanges and shifts in caregiving responsibilities.

We also found that the more intense one’sdepressive symptoms, the more likely one is toappraise his or her marriage more negativelythan one’s spouse. This finding is consistentwith studies demonstrating that depressedmood may negatively bias one’s subjectiveassessments of his or her relationships andexperiences (Futterman et al., 1990; Hirschfieldet al., 1989). Our results suggest further thatdepressive symptoms among married elderscan negatively affect spousal relations throughincreased imbalances in marital perceptionsbecause such imbalances can undermine theotherwise protective function of marriage inold age.

Our findings have potentially important impli-cations for understanding strains and rewardsparticular to long-term marriages. Social con-structionist views on marriage presume thatspouses develop a shared understanding andknowledge of their relationship, particularlyover long periods of time (Berger & Kellner,1964). Our analysis, however, reveals that olderspouses may offer divergent appraisals, particu-larly during periods of stress or compromisedhealth. Physical and cognitive declines maycreate new and unanticipated challenges formarried couples and may alter long-establishedpatterns of communication, support, and give-and-take interactions. The erosion of marital

506 Journal of Marriage and Family

‘‘consensus’’ or ‘‘shared meaning’’ may com-promise the quality of the marital relation-ship and partners’ individual well-being (Berger& Kellner).

Scholars and practitioners should attend notonly to the individual physical and mental healthneeds of older married persons but also tointeractions between spouses and each partner’sperceptions of and reactions to such interactions.Although the treatment of geriatric depression,for example, is critical for ensuring a high qualityof life of depressed older adults, our resultssuggest that such treatments also may help topreserve the quality of the marriage and may helpto ensure that both partners adhere to an agreed-upon view of the union. We caution, however,that our results do not show definitively whetherdepressive symptoms lead to discrepant maritalassessments or whether these discrepanciesaffect the partners’ depressive symptoms. Ourfindings do suggest that practitioners should nottreat marital quality and each partner’s moodas isolated attributes but rather as mutuallyinfluential factors that carry implications forboth partners’ well-being.

Discrepancies and PsychologicalAdjustment of Bereaved Spouses

We hypothesized that discrepant marital qualityassessments would affect psychological adjust-ment to loss (H1). We expected that personswho appraised their marriage more positivelythen their spouse would go on to experienceless severe grief symptoms (H2), whereas thoseoffering more negative appraisals would havemore severe grief symptoms (H3). We foundonly modest support for H1 and no support forH2 and H3. To the contrary, we found that per-sons offering more positive marital appraisalsthan their spouse experienced elevated griefsymptoms.

Regarding H1, we found that discrepantassessments do not uniformly affect adjustmentto loss. Neither depressive symptoms, anxiety,nor yearning are affected by discrepant mari-tal quality assessments. Anger is the only oneof the four outcomes affected. Regarding oursecond two hypotheses, we found that bereavedpersons who had rated their marriage more pos-itively than their spouse reported anger levelsthat were nearly 0.75 SD higher than thosewhose marital quality assessments convergedwith their spouses. This effect remained large

and significant even after the main effect of bothrespondent’s and spouse’s marital quality assess-ments were controlled. This finding is surprisingand contrary to our initial expectation. We sus-pect that one of two processes may explain thecounterintuitive finding.

First, the discrepancy could indicate animbalance in the love and support exchangedin the marriage, which violates married persons’taken-for-granted assumptions about consensusin marriage. Second, the discrepancy couldreflect the surviving spouse’s tendency to‘‘idealistically distort’’ the positive attributes ofthe late spouse and late marriage (Fowers, Lyons,& Montel, 1996). Although we cannot evaluatedirectly either explanation, our interpretationsare guided by two conceptual literatures: theinterpersonal and social sources of anger and thetendency to offer positively biased assessmentsof one’s romantic relationships.

Anger is conceptualized as an emotionalresponse to actions or events that violate orchallenge one’s values (de Rivera & Grinkis,1986; Frijda, 1993). Widely held values amongmarried couples—particularly those in long-term marriages—are that both partners shouldlove and care for each other and the partnersshould adopt a similar, shared view of themarriage. When these edicts are violated andcannot be ‘‘undone’’ or repaired because one’sspouse has died, the survivor may experiencefrustration and elevated anger symptoms.

We had expected that the persons who helda more critical view of the marriage wouldfeel frustration at their inability to undo theunhappiness that they might have inflicted ontheir spouse. One possible explanation for ourcounterintuitive finding is that the partners whoviewed the marriage more positively may feelfrustrated that they could not sustain their lovedone’s life. They may view protecting and sus-taining their spouse’s life as an integral partof the marital bargain. Moreover, they may feel‘‘cheated’’ for having a greater emotional invest-ment in their marriage and for reporting moreintense love or attachment than the now deceasedspouse.

An alternative, although complementary,interpretation is that an overly positive maritalassessment offered by the respondent, relativeto his or her spouse, could reflect ‘‘idealisticdistortions’’ about one’s marriage (Fowers et al.,1996). Multiple studies document that marriedpersons tend to endorse unrealistically positive

Marital Quality Discrepancies and Bereavement 507

descriptions of their romantic relationship andpartner (Fowers et al.; Gagne & Lydon, 2004).In general, these upwardly biased assessmentsare associated with a range of positive psy-chological attributes, including a tendency toattribute positive events and outcomes to one’sspouse (Fincham & Bradburn, 1987) and lowerlevels of conflict in one’s relationship (Murray& Holmes, 1997).

Our study suggests, however, that suchidealistic distortions may take a psychologicaltoll after the marriage ends. Taylor andBrown (1994) observed that persons who holdunrealistically positive assessments of one’s selfand one’s relationship (i.e., optimistic illusions)also tend to overestimate their ability to controlmost personal situations and underestimate thelikelihood that a negative event will befall them.They may be blindsided and overwhelmed by thedeath of their spouse and the loss of a relationshipthat they idealized (Martz et al., 1998). Theloss may seem particularly unfair and thus mayelicit anger—rather than sadness—among thebereaved. Consistent with this interpretation,a longitudinal study of college students foundthat the more idealist their beliefs about theirromantic relationship, the greater difficulty theyhad in adjusting to relationship dissolutionbecause their sense of security was undermined(Helgeson, 1994).

In sum, social constructionist perspectivesemphasize that a shared definition of the situationis critical for the effective functioning of a dyadicrelationship (Berger & Kellner, 1964). We foundthat when spouses hold divergent perspectiveson their relationship, the consequences transcendthe boundaries of the dyad and affect thewell-being of the bereaved spouse, even afterthe dyadic relationship has been dissolved bywidowhood.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study has several limitations. First, becauseof the relatively small number of bereavedspouses at the 6-month follow-up, we couldnot explore subgroup differences in adjustmentto loss. Although we investigated genderdifferences in the effects of marital qualitydiscrepancies on survivor well-being, we didnot detect any statistically significant patterns,perhaps because of our small sample size andlimited statistical power. Future studies shouldconsider a broader array of contextual and

individual characteristics that may condition theeffects of discrepancies on the well-being of bothmarried and bereaved spouses. For example, arethe psychological consequences of discrepanciescontingent upon the health of both partners priorto loss? Such investigations will help researchersto identify those persons for whom maritalquality discrepancies may be associated withparticularly distressing bereavement outcomes.

Second, we considered only the short-termconsequences of discrepancies on bereavedspouses. Future analyses should explore whetherthe effects documented here persist in the longerterm and whether effects for the outcomes ofanxiety, depressive symptoms, or yearning are‘‘delayed’’ (Freud, 1917/1959) and emerge onlyas more time has elapsed since the loss.

Third, we assessed only a limited setof potential correlates of discrepant spousalassessments. Future studies should considera fuller set of individual- and couple-levelcharacteristics and should do a more rigorousassessment of the ways that measurement errormight contribute to such discrepancies. Finally,our analyses of the correlates of discrepancyrelied on a single wave of data; thus, we cannotdraw causal inferences about the relationshipbetween depressive symptoms of respondentsand spouses and discrepancies in their maritalperceptions. Future studies using multiple wavesof dyadic data and multiple indicators of maritalquality could investigate whether being marriedto a depressed person indeed deprives oneof mutuality in the relationship and whetherspouses’ mental health contributes to discrepantviews of marriage among older couples.

Despite these limitations, our findings haveimplications for studying marriage and spousalloss in later life. Persons who rate their mar-riage more positively than their spouse went onto have significantly elevated anger symptoms.Anger is considered among the most problem-atic grief symptoms because it is linked to socialisolation and rejection of social support amongthe bereaved (Parkes & Weiss, 1983). Althoughsocial gerontologists conceptualize widowhoodas an acute crisis and propose interventions tohelp the newly bereaved to adjust to the loss(Wortman & Silver, 2001), our results suggestthat attention also should be paid to older marriedpersons who are in relationships marked by lowlevels of consensus.

Our findings also have broad implicationsfor family scholars, who typically rely on just

508 Journal of Marriage and Family

one partner’s assessment of marital quality.Our results reveal that spouses—even thosein long-term marriages—may offer divergentappraisals of a single dyadic relationship, andthose discrepancies are most acute when onepartner is experiencing a major stressor, suchas caregiving demands, illness, or depressivesymptoms. Studies linking marital quality to abroad array of life course outcomes—includingrisk of divorce, partner’s physical and mentalhealth, and children’s outcomes—may revealvery different patterns if the marital assessmentsconsidered capture both spouses’ views, as wellas discrepancies therein.

REFERENCES

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimen-tal, and theoretical aspects. New York: Harper &Row.

Berger, P., & Kellner, H. (1964). Marriage andthe construction of reality: An exercise in themicrosociology of knowledge. Diogenes, 46,1 – 25.

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Per-spective and method. Berkeley: University ofCalifornia Press.

Boelen, P. A., Stroebe, M. S., Henk, A. W., &Zjierveld, A. M. (2006). Continuing bonds andgrief: A prospective analysis. Death Studies, 30,767 – 776.

Bonanno, G. A., Wortman, C. B., Lehman, D. R.,Tweed, R. G., Haring, M., Sonnega, J., Carr, D.,& Nesse, R. M. (2002). Resilience to loss andchronic grief: A prospective study from pre-lossto 18 months post-loss. Journal of Personality andSocial Psychology, 83, 1150 – 1164.

Booth, A., & Johnson, D. R. (1994). Declining healthand marital quality. Journal of Marriage and theFamily, 56, 218 – 223.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Loss: Sadness and depression.Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. New York: BasicBooks.

Byrne, D., & Blaylock, B. (1963). Similarity andassumed similarity of attitudes among husbandsand wives. Journal of Abnormal and SocialPsychology, 67, 636 – 640.

Carr, D. (2004). Black/white differences in psycho-logical adjustment to spousal loss among olderadults. Research on Aging, 26, 591 – 622.

Carr, D., House, J. S., Kessler, R. C., Nesse, R. M.,Sonnega, J., & Wortman, C. (2000). Maritalquality and psychological adjustment to wid-owhood among older adults: A longitudinalanalysis. Journal of Gerontology: Series B:Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 55B,S197 – S207.

Carr, D., House, J. S., Wortman, C., Nesse, R., &Kessler, R. C. (2001). Psychological adjustmentsto sudden and anticipated spousal loss among olderwidowed persons. Journals of Gerontology, 56B,S237 – 248.

Conger, R. D., Elder, G. H., Jr., Lorenz, F. O.,Simons, R. L., Whitbeck, L. B., Huck, S., &Melby, J. N. (1990). Linking economic hardship tomarital quality and instability. Journal of Marriageand the Family, 52, 643 – 656.

Davila, J., Bradbury, T. N., Cohan, C. L., &Tochluk, S. (1997). Marital functioning anddepressive symptoms: Evidence for a stress gen-eration model. Journal of Personality and SocialPsychology, 73, 849 – 861.

de Rivera, J. H., & Grinkis, C. (1986). Emotions associal relationships. Motivation and Emotion, 10,351 – 369.

Deal, J. E., Wampler, K. S., & Halverson, C. F., Jr.(1992). The importance of similarity in the maritalrelationship. Family Process, 31, 369 – 382.

Derogatis, L. R., & Cleary, P. A. (1977). Confirma-tion of the dimensional structure of the SCL−90:A study in construct validation. Journal of ClinicalPsychology, 33, 981 – 989.

Feinglass, J., Lin, S., Thompson, J., Sudano, J.,Dunlop, D., Song, J., & and Baker, D. W. (2007).Baseline health, socioeconomic status, and 10-yearmortality among older middle-aged Americans:Findings from the Health and Retirement Study,1992 – 2002. Journal of Gerontology: Psychologi-cal Sciences, 62, S209 – S217.

Fincham, F. D., & Bradbury, T. N. (1987). Theimpact of attributions on marriage: A longitudinalanalysis. Journal of Personality and SocialPsychology, 53, 510 – 517.

Fowers, B. J., Lyons, E. M., & Montel, K. H. (1996).Positive marital illusions: Self-enhancement orrelationship enhancement? Journal of FamilyPsychology, 10, 192 – 208.

Freud, S. (1959). Mourning and melancholia. InJ. Strachey (Ed. and Trans.), The standard editionof the complete psychological works of SigmundFreud (Vol. 14, pp. 243 – 258). London: HogarthPress. (Original work published 1917)

Frijda, N. H. (1993). The place of appraisal inemotions. Cognition and Emotion, 7, 357 – 387.

Futterman, A., Gallagher, D., Thompson, L. W.,Lovett, S., & Gilewski, M. (1990). Retrospectiveassessment of marital adjustment and depressionduring the first two years of spousal bereavement.Psychology and Aging, 5, 277 – 283.

Gagne, F. M., & Lydon, J. E. (2004). Bias andaccuracy in close relationships: An integrativereview. Personality and Social Psychology Review,8, 322 – 338.

Goodwin, P. Y. (2003). African American andEuropean American women’s marital well-being.Journal of Marriage and Family, 54, 550 – 560.

Marital Quality Discrepancies and Bereavement 509

Gordon, P., & Perrone, K. (2004). When spousesbecome caregivers: Counseling implications foryounger couples. Journal of Rehabilitation, 70,7 – 33.

Helgeson, V. S. (1994). The effects of self-beliefs andrelationships beliefs on adjustment to a relationshipstressor. Personal Relationships, 1, 241 – 258.

Heller, P. E., & Wood, B. (1998). The processof intimacy: Similarity, understanding and gen-der. Journal of Marital Family Therapy, 24,273 – 288.

Hendrickx, J., de Graaf, N., Lammers, J., & Ultee, W.(1993). Models for status inconsistency andmobility: A comparison of the approaches by Hopeand Sobel with the mainstream square additivemodel. Quantity and Quality, 27, 335 – 352.

Hirschfield, R. M., Klerman, G. L., Lavori, P., Keller,M. B., Griffith, P., & Coryell, W. (1989). Premor-bid personality assessments of first onset of majordepression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46,345 – 350.

Jacobs, S. (1993). Pathological grief: Maladaptationto loss. Washington, DC: American PsychiatricPress.

Jacobs, S., Kasl, S., & Ostfeld, A. (1986). Themeasurement of grief: Bereaved versus non-bereaved. Hospice Journal, 2, 21 – 36.

Kalmijn, M. (1998). Intermarriage and homogamy:Causes, patterns, trends. Annual Review ofSociology, 24, 395 – 421.

Kenny, D. A., & Acitelli, L. K. (1994). Measuringsimilarity in couples. Journal of Family Psychol-ogy, 8, 417 – 431.

Kenny, D. A., & Acitelli, L. K. (2001). Accuracyand bias in perception of the partner in a closerelationship. Journal of Personality and SocialPsychology, 80, 439 – 448.

Kruglanski, A. W. (1989). Lay epistemics and humanknowledge: Cognitive and motivational bases. NewYork: Plenum.

Lee, G. R., DeMaris, A., Bavin, S., & Sullivan, R.(2001). Gender differences in the depressiveeffect of widowhood in later life. Journalof Gerontolology: Psychological Science, 56,S56 – S61.

Liang, J., Krause, N. M., & Bennett, J. M. (2001).Social exchange and well-being: Is giving betterthan receiving? Psychology and Aging, 16,511 – 523.

Lopata, H. Z. (1981). Widowhood and husbandsanctification. Journal of Marriage and the Family,43, 439 – 450.

Mancini, A. D., & Bonanno, G. A. (2006). Maritalcloseness, functional disability, and adjustment inlate life. Psychology and Aging, 21, 600 – 610.

Martz, J. M., Verette, J., Arriaga, S. B., Slovik, L. F.,Fox, C. L., & Rusbult, C. E. (1998). Positive

illusion in close relationships. Personal Relation-ships, 5, 159 – 181.

Miech, R., Power, C., & Eaton, W. W. (2007).Disparities in psychological distress acrosseducation and sex: A longitudinal analysis of theirpersistence within a cohort over 19 years. Annalsof Epidemiology, 17, 289 – 295.

Murray, S. L., & Holmes, J. G. (1997). A leap offaith? Positive illusions in romantic relationships.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23,586 – 604.

Parkes, C. M., & Weiss, R. S. (1983). Recovery frombereavement. New York: Basic Books.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the generalpopulation. Applied Psychological Measurement,1, 385 – 401.

Schulz, R., Boerner, K., & Hebert, R. S. (2008). Care-giving and bereavement. In M. S. Stroebe, R. O.Hansson, H. Schut, & W. Stroebe (Eds.), Hand-book of bereavement research and prac-tice: Advances in theory and intervention(pp. 265 – 285). Washington, DC: American Psy-chological Association.

Schumacher, K. L. (1995). Family caregiver roleacquisition: Role-making through situated inter-action. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 9,211 – 271.

Singh, B., & Raphael, B. (1981). Post disastermorbidity of the bereaved: A possible role forpreventive psychiatry. Journal of Nervous andMental Disease, 169, 203 – 212.

Spanier, G. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment:New scales for assessing the quality of marriageand similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and theFamily, 42, 15 – 27.

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1994). Positiveillusions and well-being revisited: Separatingfact from fiction. Psychological Bulletin, 116,21 – 27.

Umberson, D., Chen, M. D., House, J. S., Hopkins,K., & Slaten, E. (1996). The effect of socialrelationships on psychological well-being: Aremen and women really so different? AmericanSociological Review, 61, 837 – 857.

Wheaton, B. (1990). Life transitions, role histories,and mental health. American Sociological Review,55, 209 – 223.

Wortman, C. B., & Silver, R. C. (2001). The mythsof coping with loss revisited. In M. S. Stroebe& R. O. Hansson (Eds.), Handbook of bereave-ment research: Consequences, coping, and care(pp. 587 – 612). Washington, DC: American Psy-chological Association.

Zisook, S., DeVaul, R., & Click, M. (1982). Measur-ing symptoms of grief and bereavement. AmericanJournal of Psychiatry, 139, 1590 – 1593.