Do Demand Curves for Stocks Slope Down in the Long...

Transcript of Do Demand Curves for Stocks Slope Down in the Long...

1

Do Demand Curves for Stocks Slope Down in the Long Run?1

Clark Liu† and Baolian Wang‡

January 2017

Abstract

The Split-Share Structure Reform in China mandated the conversion of nontradable local A-shares into tradable status and increased A-share float. This paper examines the long-term pricing effects of the increased float. Given that foreign B-shares were not directly affected by this reform, we use B-share price to control for possible changes in firm fundamentals. We find that, across firms, larger increases in A-share float leads to larger decreases in A-share price relative to B-share price, even up to around ten years after the reform, suggesting that demand curves slope down in the long run. We also find that larger increase in float leads to larger decrease in turnover and volatility, and demand curves are steeper when divergence of opinion is larger, consistent with the theory modelling investors with divergence of opinion.

Keywords: long-term demand curve; divergence of opinion; Split-Share Structure Reform; A/B share; lack of substitutes

JEL codes: G02, G12, G15

1 The authors are grateful for the valuable comments received from Nicholas Barberis, Justin Birru, Zhi Da, Andrey Ermolov, Bill Francis, Pengjie Gao, Zhiguo He, Shiyang Huang, Tse-Chun Lin, Abhiroop Mukherjee, Jay Ritter, Mark Seasholes, Andrei Shleifer, Dragon Yongjun Tang, Tan Wang, John Kuo-Chiang Wei, Yu Xu, Hongjun Yan, Jialin Yu, Chu Zhang, Hong Zhang and seminar participants at Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Hong Kong University, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, the 2016 Financial Markets Workshop (Fordham, NYU and Imperial College) and Tsinghua University (PBC School of Finance and School of Economics and Management). All errors are the authors’ responsibility. † PBC School of Finance, Tsinghua University. Email: [email protected]. ‡ Gabelli School of Business, Fordham University. Email: [email protected].

2

Do Demand Curves for Stocks Slope Down in the Long Run?

January 2017

Abstract

The Split-Share Structure Reform in China mandated the conversion of nontradable local A-shares into tradable status and increased A-share float. This paper examines the long-term pricing effects of the increased float. Given that foreign B-shares were not directly affected by this reform, we use B-share price to control for possible changes in firm fundamentals. We find that, across firms, larger increases in A-share float leads to larger decreases in A-share price relative to B-share price, even up to around ten years after the reform, suggesting that demand curves slope down in the long run. We also find that larger increase in float leads to larger decrease in turnover and volatility, and demand curves are steeper when divergence of opinion is larger, consistent with the theory modelling investors with divergence of opinion.

Keywords: long-term demand curve; divergence of opinion; Split-Share Structure Reform; A/B share; lack of substitutes

JEL codes: G02, G12, G15

3

1. Introduction

The traditional finance theory argues that, in a perfect capital market, stock price equals

expected future cash flows discounted by return that reflects systematic risk, so the demand

curve for a stock should be (nearly) horizontal (Scholes, 1972). In such a perfect market, a

change of an individual stock’s share supply can only affect its own stock price when the supply

change affects its expected future cash flow, its systematic risk loading, or the market risk

premium. A change of a stock’s share supply (even it is a large change relative to its own share

base) typically has very little effect on its systematic risk loading or the market risk premium. If

expected cash flow per share is not affected, the share supply should have (virtually) no price

impact. Petajisto (2009) shows that, in a CAPM world without any frictions, a stock’s addition to

the S&P 500 index should not affect its price by more than a few basis points.

There are two alternative hypotheses that deviate from the perfect market hypothesis. One is

the price pressure hypothesis, which asserts that, because of stock market’s limited risk

absorptive capability and slow-moving capital, uninformative excess demand can cause a stock’s

price to temporarily diverge from its fundamental value. Slow-moving capital can result from

many factors such as search costs for trading counterparties, time to deploy new capital, limited

attention, or market segmentation (Merton, 1987; Mitchell, Pedersen, and Pulvino, 2007; Duffie,

2010; Greenwood, Hanson, and Liao, 2015). Under this hypothesis, the price deviation is

temporary and will eventually reverse.

The second alternative is the long-term downward sloping demand curve hypothesis. One

possible reason is that investors have heterogeneous valuations. Heterogeneous valuations can

lead to demand schedules (Miller, 1977).2 If heterogeneous valuations persist and short-sale

2 We discuss the related theories in more details in Section 3.

4

constraint is binding, demand curves can be downward sloping in the long run. It is widely

documented that both short-term (i.e., from a few minutes to a few hours) and medium-term (i.e.,

from a few days to a few months) demand curves for stocks are downward sloping (Scholes,

1972; Holthausen, Leftwich, and Mayers, 1990; Shleifer, 1986; Chang, Hong, and Liskovich,

2014; Beneish and Whaley, 1996; Lynch and Mendenhall, 1997; Wurgler and Zhuravskaya,

2002; Greenwood, 2005). However, the shape of the long-term (i.e., years) demand curves is

much less studied and the existing evidence is also much less conclusive.3,4 Perhaps this is

because of methodological limitations. Most existing empirical studies investigate the shape of

demand curves by analyzing price reactions to events of supply/demand shocks using the

standard event study method.5 Reaching a conclusion about long-term demand curves requires an

estimation window so long that the ability of the standard event study method to pin down

changes in a statistically meaningful way is hampered; in addition, firm fundamentals may

change systematically in the long term. 6 In this paper, we circumvent these problems and

develop an empirical strategy to investigate the shape of long-term demand curves for horizons

up to around ten years.

3 It is worth mentioning that our terminologies may differ from those that have been used by some existing studies. Some of the existing studies define a few weeks or a few months as “long-term” or “permanent”, but we define this as “medium-term”. We define periods of longer than a year as “long-term”. Our empirical design enables us to examine horizons up to around ten years. 4 For example, Chan, Kot, and Tang (2013) find that, in the five years after S&P 500 additions and deletions, both added stocks and deleted stocks deliver abnormally high returns. The evidence that both added stocks and deleted stocks have positive long-run abnormal returns cannot be explained by downward sloping demand curves. 5 These studies include studies on block trades, index additions/deletions, index redefinitions, and IPO lockup expirations, among others. We discuss these in more detail in Section 2. 6 Wurgler and Zhuravskaya (2002, p. 586) state that “given no generally accepted way to adjust for risk, we do not investigate the long-run effect issue anew.” Hau, Massa, and Peress (2010) have a similar argument in their paper (see p. 1714). There is some evidence on changing firm fundamentals after they are added or deleted from S&P 500. Denis, McConnell, Ovtchinnikov, and Yu (2003) find that additions to the S&P 500 are associated with an increase in both analysts’ forecasted earnings and realized earnings. Hegde and McDermott (2003) document an increase in the liquidity of stocks added into the S&P 500 index. Chan, Kot, and Tang (2013) find that institutional ownership and liquidity increase for both stocks added to S&P 500 and also stocks deleted from S&P 500. Massa, Peyer, and Tong (2005) document an increase in equity financing and investment in the two years after stocks are added into S&P 500.

5

Investigation of the shape of long-term demand curves is important for several reasons. First,

it will help us understand the nature of financial market frictions. Are demand curves downward

sloping in the long term? If so, why? Second, as argued by Shleifer (1986), if demand curves are

downward sloping in the long term, some fundamental finance theories require reexamination;

for example, the assumptions underlying the Modigliani and Miller (1958) theorem are violated.

Firms may bypass positive-net-present-value projects in anticipation of a long-term price impact

of equity issuance, even in the absence of managerial myopia. In comparison, the shape of short-

term and medium-term demand curves may not matter as much.

In order to investigate the shape of long-term demand curves, we need to measure the long-

term price effect of exogenous supply shocks. The Chinese A/B share market around the Split-

Share Structure Reform provides a suitable empirical setting.7 Several dozen Chinese firms

issued both A- and B-shares. A-share and B-share have the same cash flow rights and voting

rights and are listed in the same stock exchanges. However, they are not fungible. One cannot

buy A-shares of a firm and sell them in the B-share market or vice versa. A- and B-shares are

also quoted and traded separately. A-shares are quoted and traded in Chinese yuan, and B-shares

are traded in foreign currencies (in U.S. dollars for B-shares listed in the Shanghai Stock

Exchange and in Hong Kong dollars for B-shares listed in the Shenzhen Stock Exchange). A-

shares are only open to domestic investors, whereas B-shares were only open to foreign investors

until February 2001, when they began to be open to domestic individual investors with foreign

currency as well. Even after February 2001, due to capital control, the two markets have

remained partially segmented (Chan, Menkveld, and Yang, 2008). Although the two shares have

the same fundamentals, on average A-shares are traded at a premium, and there are large cross-

7 For more details on the Chinese stock markets and the Split-Share Structure Reform, please see Section 2.

6

sectional and time-series variations of the A/B share premiums (Fernald and Rogers, 2002; Chan,

Menkveld, and Yang, 2008).

Examining A/B share premiums largely overcomes the methodological limitations faced by

the standard event study on returns. In standard event studies of long-term effects, we do not

have a perfect benchmark asset pricing model to adjust risks, variance of the cumulative returns

also grows with horizons, and in the long term, firms may endogenously adopt policies in

response to supply shocks. Because A/B shares have the same fundamentals, one share’s price

works naturally as a benchmark for the other share. Empirically, in our sample period, A-share

price and B-share price comove strongly with each other with an average correlation coefficient

of 0.875 and are cointegrated for most firms.8 Therefore, we can circumvent the difficulty of risk

adjustment, growing variance and changing firm fundamentals by examining long-term A/B

share premium evolvement.9

We use the Split-Share Structure Reform of the A-shares as an exogenous event of A-share

supply shocks to investigate the shape of demand curves. The reform started in 2005, and most

firms finished the reform by the end of 2006. Before this reform, most Chinese firms had two

types of A-shares: tradable A-shares and nontradable A-shares. More than two thirds of all A-

shares were nontradable. The reform made all A-shares tradable after a period of lockup, with

negotiated compensation from nontradable shareholders to tradable shareholders. This reform

increased the supply of A-shares but had no direct impact on B-share supply. The ratio of the

8Albagli, Gao, and Wang (2013) document that, in the period between 1992 and 2008, A-share and B-share of the same firm comove less than B-share with B-share index. We find that this result is unique for their sample period. In our sample period, A-share and B-share of the same firm comove more than B-share with B-share index. These different results are possibly due to the deeper integration of the Chinese financial market with the global financial market in more recent years. The results are available upon request. 9 Individual investors are allowed to invest in the B-shares. It is possible that A-shares’ price impact may spill over to B-shares. However, we think this is unlikely because of the foreign currency regulation in China and because, empirically, only a very small fraction of investors participate in the B-share market even B-shares are much cheaper. If there is any spillover effect, A/B share premium change will underestimate the true effect of demand curves.

7

total number of A-shares to the number of tradable A-shares (“ΔFloat”) before the reform acts

naturally as a measure of A-share supply increase: a larger ΔFloat means a larger increase in A-

share supply. This event is a market-level event and is largely out of the control of any individual

firm.

We find that ΔFloat adversely predicts the change of A/B share premium in the reform

period. The effect of ΔFloat initially increases in the first two to three years after the reform and

then gradually decreases. Right after the completion of the reform, a 100% increase of tradable

shares (when ΔFloat=1) is associated with a 2.8% decrease of A/B share premium. The effect

reaches its peak in 24 months, when a 100% increase of tradable shares is associated with a 7.9%

decrease of A/B share premium. However, even up to December 2014, which marks the end of

our sample period, a 100% increase of tradable shares is still associated with a 3.5% decrease of

A/B share premium. This suggests that demand curves are downward sloping even up to around

ten years after the supply shocks. The initial increase in the effect of ΔFloat is consistent with the

fact that most nontradable shares’ lockup expires in two to three years after the reform, and the

long-run partial reversal suggests that longer-term demand curves are less downward sloping

than shorter-term demand curves. These results are robust after controlling for a number of firm

characteristics.10

These results cannot be explained by change of systematic risks or liquidity. We find no

evidence that change of systematic risks is associated with ΔFloat. A-share liquidity improves on

average, and the increase is stronger for firms with higher ΔFloat. Combining with the widely

documented fact that liquidity improvement should predict an increase in price (e.g., Amihud

10 The existence of the B-shares may make the demand curves for A-shares less steep. A-share investors may learn from B-share price and the existence of the B-share may reduce investors’ divergence of opinion. To some extent, B-shares are also substitutes to A-shares, though it is not that easy for A-share investors to trade B-shares due to the foreign currency control in China.

8

and Mendelson, 1986), the liquidity effect predicts ΔFloat to be positively associated with

change in A/B premium. However, we find the opposite result, suggesting that the demand curve

effect is dominant. Ignoring the opposite effect of liquidity may actually underestimate the slope

of demand curves.

Another concern is that ΔFloat may be correlated with change of corporate governance. The

main purpose of the reform was to align the incentives of the small tradable shareholders and the

controlling nontradable shareholders (Liao, Liu, and Wang, 2014). It has also been shown that

foreign investors care more about corporate governance than domestic investors (Leuz, Lins, and

Warnock, 2010). If this is also true for A/B share investors and corporate governance improves

more for firms with more nontradable shares (i.e., higher ΔFloat), we should expect that, in the

event period, B-share price increases more than A-share price, and more so for high ΔFloat firms.

However, we find that the change of A/B share premium in the event period is purely driven by

decrease of A-share price, suggesting that corporate governance change cannot explain our

finding. Another possibility is that A-shareholders may prefer to state ownership or large block

shareholders. The reform increases the probability for them to leave and lead to A-share price

drop. If B-shareholders are neutral, B-share price will not change. We find that both state-owned

nontradable shares and non-state-owned nontradable shares, and both nontradable shares owned

by large shareholders and nontradable shares owned by small shareholders have similar negative

effect on A/B share premium, suggesting that the results are not driven by A-shareholders’

preference to state ownership or large block ownership.

A few limits to arbitrage factors prevent the demand curves from being flat. First, short-sales

constraint is binding and pessimistic investors cannot sell short. Second, we find that lack of

substitutes matters but cannot fully explain the results. One possible interpretation is that some

9

investors form their firm-specific opinions and they do not regard even similar stocks as good

substitutes. Third, the price effects we document only translate into a very small expected return

difference between different A-shares, which is unlikely to attract arbitrageurs.

One plausible reason for downward sloping demand curves is divergence of opinion.11 In the

presence of short-sale constraints, divergence of opinion leads to overvaluation of stocks, which

is negatively correlated with share supply (Miller, 1977; Chen, Hong, and Stein, 2002;

Scheinkman and Xiong, 2003; Hong, Scheinkman, and Xiong, 2006). These models also predict

that the marginal effect of share supply is larger when divergence of opinion is larger.

Consistently, we find that the effect of ΔFloat on A/B share premium change is more

pronounced for stocks of which A-share turnover – our proxy for divergence of opinion – was

higher in the period before the reform. Scheinkman and Xiong (2003) and Hong, Scheinkman,

and Xiong (2006) further predict that, in dynamic models, share supply is also negatively

correlated with turnover and return volatility. Consistent with this, we find that larger ΔFloat

predicts a larger decrease in turnover and volatility.

Given that ΔFloat is inversely related to A-share price change, do tradable shareholders

expect this and ask for proper compensation? If so, are they compensated based on short-term or

long-term price impact? We find that an average tradable shareholder loses if he/she closes

position when price impact is at its peak but gains if he/she is patient enough to wait until seven

to nine years after the reform. We also find that tradable shareholders receive higher

compensation when ΔFloat is higher, suggesting that investors indeed take price impact into

account when negotiating compensation. However, the results show that the sensitivity of

compensation to ΔFloat is lower than the sensitivity of the change of A/B share premium to

11 This conjecture goes back at least to Shleifer (1986).

10

ΔFloat, suggesting that tradable shareholders of firms with high ΔFloat are relatively under-

compensated than tradable shareholders of firms with low ΔFloat.

Our study offers two principal contributions. First, we find strong evidence that demand

curves are downward sloping in horizons up to around ten years. Most existing studies have not

investigated horizons longer than six months. Our finding suggests that, even up to around ten

years, factors unrelated to systematic risk can have a first-order effect on stock pricing. This also

suggests that some limits to arbitrage are binding even in the long run. Second, we provide

evidence that is consistent with divergence of opinion-based interpretation of downward sloping

demand curves.

The paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2, we discuss related literature. In Section 3, we

develop our hypotheses. In Section 4, we discuss the institutional background of the Chinese

stock market and the Split-Share Structure Reform. Section 5 presents our data. The main results

are in Section 6. In Section 7, we provide evidence on why demand curves are downward sloping.

In Section 8, we test how tradable shareholders are compensated for downward sloping demand

curves. Concluding remarks are presented in Section 9.

2. Related literature

Our study is related to a few streams of existing literature. The first stream of literature

examines the price responses to block trades (Scholes, 1972; Kraus and Stoll, 1972; Holthausen,

Leftwich, and Mayers, 1990) and finds that stock price reacts positively (negatively) to buyer-

initiated (seller-initiated) block trades. Studies find that part of the initial price reaction reverses

in a short-term period, while part persists (Holthausen, Leftwich, and Mayers, 1990). The

reversal effect is consistent with a downward sloping short-term demand curve, and the

11

explanation typically given for the persistent effect is that block trades signal useful news to the

market. These studies examine very short horizons, from a few minutes to a few hours.

The second stream of literature examines price responses to stocks adding to or deleting from

the Standard and Poor’s (S&P) 500 index or other widely-followed indices (Shleifer, 1986;

Harris and Gurel, 1986; Goetzmann and Garry, 1986; Dhillon and Johnson, 1991; Beneish and

Whaley, 1996; Lynch and Mendenhall, 1997; Wurgler and Zhuravskaya, 2002; Chen, Noronha,

and Singal, 2004; Chang, Hong, and Liskovich, 2014), redefinitions of indices (Krau, Mehrotra,

and Morck, 2000; Greenwood, 2005; Chakrabarti, Huang, Jayaraman, and Lee, 2005; Hau,

Massa, and Peress, 2010), share repurchases (Bagwell, 1992), IPO lockup expiration (Ofek and

Richardson, 2000; Field and Hanka, 2001; Hong, Scheinkman, and Xiong, 2006), price pressure

on acquirer stocks around mergers (Mitchell, Pulvino, and Stafford, 2004), Treasury security

price reaction to Treasury auctions (Lou, Yan, and Zhang, 2013), the price impact of mutual fund

flows (Coval and Stafford, 2007; Frazzini and Lamont, 2008; Lou, 2012), and other forms of

supply shocks (Greenwood, 2009). Consistent with downward sloping demand curves, all these

studies document significant price reactions around the event dates, and most also find that the

price effects persist at least a few weeks to a few months after the event dates.12 However, most

studies have not investigated horizons longer than six months.13

Among the above studies, the longest horizon that has been examined is around two to three

years (Coval and Stafford, 2007; Frazzini and Lamont, 2008; Lou, 2012). This is still

12 Harris and Gruel (1986) and Luo, Yan, and Zhang (2013) are two exceptions. Harris and Gruel (1986) find, in their sample, that stocks added to S&P 500 have a significantly positive short-term announcement return reaction, which completely reverses in two weeks. However, Dhillon and Johnson (1991) argue that Harris and Gurel’s (1986) finding may be specific to their method of risk adjustment. Luo, Yan, and Zhang (2013) document that Treasury security prices in the secondary market decrease significantly in the few days before Treasury auctions and recover shortly thereafter. The different finding between the equity market and the Treasury market may be due to the fact that the Treasury market is more liquid and the substitutability across Treasury securities is also better than that across stocks. 13 Please see Table A1 in the Appendix for a summary.

12

significantly shorter than the time period we investigate in this paper. Coval and Stafford (2007)

find that demand shocks driven by mutual fund outflows (inflows) cause stock price to decrease

(increase) and that the recovery takes around two years. The demand shocks induced by mutual

fund flows are temporary. In our study, float changes permanently, which may explain why the

price impact lasts much longer in our empirical setting.

There is also a literature on corporate financing implications of downward sloping demand

curves. Hodrick (1999) studies tender offer choice in share repurchases and find that firms that

choose Dutch auctions over fixed-price tender offers tend to face more elastic demand curves.

Baker, Coval, and Stein (2007) investigate how downward sloping demand curves affect price

pressure in stock-for-stock mergers. They also discuss how downward sloping demand curves

affect the choice of payment methods in mergers, and corporate equity financing decision

choices between seasoned equity offerings, stock-based compensation programs and stock-for-

stock mergers. Gao and Ritter (2010) document that investment bank’s marketing efforts in

seasoned equity offering can flatten the issuer’s demand curves in the horizon of several months.

Our study is also related to the literature on how divergence of opinion combining with short-

sales constraints affects asset prices and trading.14 On the theory side, this has been fruitfully

discussed (Miller, 1977; Harrison and Kreps, 1978; Chen, Hong, and Stein, 2002; Hong and

Stein, 2003; Scheinkman and Xiong, 2003; Hong, Scheinkman, and Xiong, 2006). Empirically,

Chen, Hong, and Stein (2002), and Diether, Malloy, and Scherbina (2002) find that stocks with

higher divergence of opinion have lower future stock returns. Xiong and Yu (2011) document

supporting evidence from the Chinese warrants market. Chen, Hong, and Stein (2001) find that

returns are more negatively skewed conditional on high trading volume. Our study complements

14 See Hong and Stein (2007) for a review.

13

these studies by documenting evidence that divergence of opinion can have long-term effects on

stock prices.

We also contribute to the literature on relative pricing between securities with identical cash

flows (Froot and Dabora, 1999). The studies most related to ours are those from the perspective

of downward sloping demand curves. Bailey and Jagtiani (1994), Stulz and Wasserfallen (1995),

and Domowitz, Glen, and Madhavan (1997) find that foreign share supply decreases foreign

shares’ prices relative to domestic shares, using data from Thailand, Switzerland, and Mexico,

respectively. Bailey, Chung, and Kang (1999) find that U.S. global fund inflows increase the

foreign shares’ price relative to domestic shares, using data from eleven countries. Sun and Tong

(2000) find that Chinese A/B share premium increases when the availability of substitutes for B-

shares (Mainland Chinese firms listed in Hong Kong) increase. These studies provide evidence

that demand curves are downward sloping. However, similar to the literature on block trades and

index additions/deletions, they do not investigate the long-term price dynamics of demand

shocks. Another difference between these studies and ours is that these studies examine how the

supply of foreign shares affects relative pricing, while we examine the demand curves for

domestic shares. It is well known that investors investing in foreign assets face more barriers

(e.g., high taxes and transaction costs, or restrictions on capital mobility) and institutional

frictions (e.g., mutual fund investment mandates), and these frictions can lead to demand

schedules (Stulz and Wasserfallen, 1995). Investigating the effect of A-shares’ supply shocks is

free of many of these frictions.

Other factors are also important in explaining A/B share premium. The existing literature has

proposed explanations of A/B share premium based on differences in risk-free discount rate

(Fernald and Rogers, 2002), different systematic risk exposures (Eun, Janakiramanan, and Lee,

14

2001), information asymmetry (Chan, Menkveld, and Yang, 2008), political risk (Karolyi, Li,

and Liao, 2009), and speculative trading (Mei, Scheinkman, and Xiong, 2009). The work most

related to ours is that of Mei, Scheinkman, and Xiong (2009), who find that, in the cross section,

A/B share premium is negatively correlated with A-share float and positively correlated with B-

share float. They also find that A-share turnover is negatively correlated with A-share float. Our

results are consistent with theirs. However, they do not examine the dynamics of demand curves

over different horizons. The Split-Share Structure Reform provides us opportunities to rule out

other possible interpretations of these correlations.

Our study is also related to the studies on the Split-Share Structure Reform. Li, Wang,

Cheung, and Jiang (2011) argue that the reform improves risk sharing between tradable and

nontradable shareholders and that improved risk sharing affects the compensation nontradable

shareholders pay to the tradable shareholders. They also find that expected price impact

positively contributes to compensation, consistent with our findings. However, they do not

examine the price impact of supply shocks directly. Firth, Lin, and Zou (2010) find that state

ownership increases compensation but that mutual fund ownership decreases compensation. Liao,

Liu, and Wang (2014) and Campello, Ribas, and Wang (2014) study how the reform affects

firms’ performance and corporate policies. Hwang, Zhang, and Zhu (2006) document that A-

share prices decrease in the period from reform announcement to completion. Li, Liao, and Shen

(2013) find that A-share price decrease is associated with the size of supply shock. Liao, Liu, and

Wang (2011) find significantly negative A-share returns around nontradable shares’ lockup

expirations. However, none of these papers investigate the long-term effects.

15

3. Hypotheses development

Many factors can lead to downward sloping demand curves. The price pressure hypothesis

asserts that demand curves can be downward sloping because of limited risk absorptive

capability and slow-moving capital. Slow-moving capital originates from many factors such as

search costs for trading counterparties, time to deploy new capital, or market segmentation

(Mitchell, Pedersen, and Pulvino, 2007; Duffie, 2010; Greenwood, Hanson, and Liao, 2015).

Under the price pressure hypothesis, eventually price will reverse.

Demand curves can be downward sloping in the long run if investors have persistent

heterogeneous valuations and face short-sales constraints (Miller, 1977). Heterogeneous

valuations can result from various sources such as divergence of opinion (Miller, 1977),

information asymmetry (Milgrom and Weber, 1982), and background factors (e.g., capital gain

tax lock-in (Bagwell, 1991)). To fully disentangle the importance of each source of

heterogeneous valuations is beyond the scope of this paper. Instead, we focus on factors that the

existing literature has developed clear implications for which we can test. Specifically, we focus

on investigating the implications of theories based on divergence of investors’ opinion (Miller,

1977; Harrison and Kreps, 1978; Scheinkman and Xiong, 2003; Hong, Scheinkman, and Xiong,

2006).

When short-sales are prohibited, stock price only reflects the beliefs of optimistic investors,

as pessimistic ones simply sit out of the market because they cannot sell short (Miller, 1977). In

equilibrium, the marginal investor’s view is such that he is indifferent between buying versus not

buying the stock. For a given distribution of investor beliefs, when float increases, investors with

views less optimistic than the current marginal investor would need to buy to clear the market,

leading to a lower equilibrium price.

16

In dynamic models (Harrison and Kreps, 1978; Scheinkman and Xiong, 2003; Hong,

Scheinkman, and Xiong, 2006), investors may pay an even higher price on the premise that they

will be able to find other investors willing to pay even more in the future. Investors can agree to

disagree if they are overconfident (i.e., if each one thinks his information is more accurate than it

really is; Scheinkman and Xiong, 2003; Hong, Scheinkman, and Xiong, 2006). The value of

resale option is smaller for a larger asset float because under a larger float a greater divergence of

opinion is needed in the future for investors to resell their shares.

Both the static model (Miller, 1997) and the dynamic models (Harrison and Kreps, 1978;

Scheinkman and Xiong, 2003; Hong, Scheinkman, and Xiong, 2006) share the same prediction

regarding the relationship between share supply and price.

Hypothesis 1: An increase in share supply is associated with a decrease in price.

Scheinkman and Xiong (2003) and Hong, Scheinkman, and Xiong (2006) also predict that

share supply will change turnover and return volatility. Trading will occur when some investors

become more optimistic than the existing long investors. This is more likely to happen when a

smaller fraction of investors are long, equivalently when the share base is smaller. Price is

determined by the belief of the marginal investor. Hence, volatility is determined by the volatility

of the changes of beliefs of marginal investor. When the share base becomes smaller, the

marginal investor’s belief becomes more extreme and more volatile, which leads to an increase

in volatility.

Hypothesis 2: An increase in share supply is associated with a decrease in turnover.

Hypothesis 3: An increase in share supply is associated with a decrease in volatility.

Divergence of opinion moderates the negative relationship between share supply and price.

Stock is priced based on the belief of the marginal investor, whose view is the least optimistic

17

among the long investors. Increase in share supply needs to be cleared by additional long

investors who are less optimistic than the current marginal investor. Therefore, price elasticity

with respect to supply change is determined by the change of optimism of the marginal investor.

For a given supply change, a larger divergence of opinion is likely to be associated with a larger

change of optimism of the marginal investors, leading to a larger price movement.15

Hypothesis 4: The elasticity of price to share supply is higher when divergence of opinion is

larger.

4. Institutional background

4.1 The Chinese stock markets

Mainland China’s two stock exchanges, the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SZE) and the

Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE), were witnessed a rapid growth since their establishment in

December 1990 and July 1991, respectively. By the end of our sample period (December 2014),

there were 2,613 listed companies, more than 120 million investors, and a market capitalization

of more than six trillion USD.16 The market is dominated by individual investors which own

around 50% of the whole market in the end of 2014.

A unique feature of the Chinese stock market is that several dozen companies issued “twin

shares” – two classes of common shares (A/B shares) with identical voting rights and cash flow

rights, listed on the same exchange. A-shares and B-shares are traded by different groups of

15 For example, suppose that there is a continuum of investors of mass one whose beliefs follow a normal distribution N(µ,σ2), and each investor can decide to either hold one share or sit out of the market. For a given level of share supply s, the marginal investor’s belief is Zs such that 1-Φ(Zs) = s. One can easily verify that ∂ / is an increasing function with respect to σ. 16 Data are from the fact books of the Shanghai Stock Exchange and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

18

investors. A-shares are traded by domestic investors, whereas B-shares were restricted to foreign

investors before February 2001; after that date, domestic individual investors who own foreign

currencies are allowed to participate in the B-share market.17 A-shares are quoted and traded in

Chinese local currency (Chinese yuan), whereas Shanghai (Shenzhen) B-shares are quoted and

traded in US (Hong Kong) dollars. Dividends to the B-share investors are in the same amount as

those to the A-share investors, but they are exchanged to the quoting currency using the

prevailing exchange rates. A-shares and B-share are not fungible. One cannot buy A-shares of a

firm and sell them in the B-share market or vice versa. Despite the lifting of the restriction in

2001, only a small fraction of domestic investors participates in the B-share market (Chan, Wang,

and Yang, 2015). The A-share market and the B-share market are still partially segmented.

4.2 The Split-Share Structure Reform

Virtually all B-shares are tradable, but there are both nontradable and tradable A-shares.18

Nontradable A-shares are mainly held by the government or “legal persons” such as enterprises

and other economic entities rather than by individuals (Sun and Tong, 2003). As indicated by

their name, only tradable shares are allowed to be traded in exchanges, while nontradable shares

are not allowed, though private transfer is allowed.19 On average, around two thirds of the shares

are nontradable, whereas the rest are tradable. The ownership of nontradable shares is typically

highly concentrated among a very small number of investors, but the ownership of tradable

shares is highly dispersed.

17 There are qualified domestic institutional investors (QDII) that have approval from the Chinese authority to use domestic funds to invest in foreign assets. There are also qualified foreign institutional investors (QFII) which have approval to invest in the A-share market. However, during our sample period, the amounts of QDII and QFII are very small and have a negligible effect on the market. 18 For A/B share firms in our sample, all B-shares are tradable. There are some nontradable B-shares for firms that are only listed in the B-share market. However, they are not in our sample. 19 The liquidity of private transfer is very limited (Chen and Xiong, 2001).

19

The split-share structure caused serious corporate governance problems. Nontradable

shareholders lack incentives to improve stock price; and as controlling shareholders, they also

tend to make equity offerings without considering their adverse effect on stock price.

Concentrated nontradable share ownership also tremendously hinders the development of the

market for corporate control (Allen, Qian, and Qian, 2005; Li, Wang, Cheung, and Jiang, 2011;

Liao, Liu, and Wang, 2014). Not surprisingly, most individual tradable share investors, being

unable to monitor, tend to be free riders and short-term speculators (Tenev, Zhang, and Brefort,

2002).

Realizing the corporate governance problems associated with the split-share structure, the

Chinese government has long planned for the conversion of nontradable shares. However, the

tradable shareholders were worried about the negative price impact of A-share supply increase.

In December 1999, the Chinese government began to reduce the state ownership by selling

nontradable shares on the market. However, the market crashed due to concerns over a flood of

new share supply, and the ownership reduction plan was withdrawn in 25 days. In June 2001, the

Chinese government made a second trial; again, the market crashed, and the reform had to be

withdrawn in June 2002.

In 2005, the Chinese government introduced the Split-Share Structure Reform. In contrast to

the previous two trials, this time the government explicitly stated that the tradable A-

shareholders must be compensated based on a mutual agreement between tradable and

nontradable shareholders. B-shareholders did not participate in the compensation plan, because

the reform did not affect the share supply of B-shares. Forms of compensation included cash,

asset restructuring, warrants, and share transfer from nontradable shareholders to tradable

20

shareholders. Share transfer is the predominant form of compensation (Li, Wang, Cheung, and

Jiang, 2011; Firth, Lin, and Zhou, 2012).

To implement the reform, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) selected two

batches of firms for a trial in April and June 2005. The first trial involved four companies, and

the second involved 41 companies. The trials were considered a success, so in August 2005 the

reform was expanded to all listed firms. By the end of 2006, the reform was completed for

companies representing over 93% of total Chinese A-share market capitalization. Most of our

sample firms also completed their reforms by December 2006.

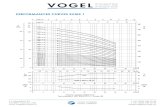

[Insert Figure 1 here]

Figure 1 shows the timeline of a typical reform for a company. On day t0, the company

announces the start of its reform and trading is suspended. The nontradable shareholders, as

represented by the board of directors, propose a compensation plan to the tradable shareholders

and then negotiation between nontradable and tradable shareholders begins. In the event of any

disagreement, the plan may be revised. Once both groups reach an agreement, the board makes

an announcement of the finalized reform plan on day t1, and trading resumes on the same day.

Trading is suspended again from the day after the shareholder registration day (day t2) until the

reform is completed (day t3). Voting takes place in the period between the registration day and

the completion day. Trading resumes after the voting outcome is announced. On average, 81

days elapse from the announcement date to the completion date.

According to the guidelines issued by the CSRC, there is a lockup period after the reform.

This lockup period has to be at least one year, and the length varies across different nontradable

investors. For investors who own less than 5% of the total number of shares of a firm, all shares

will become tradable one year after reform completion. Investors who own more than 5%

21

(typically strategic shareholders and very often the controlling shareholder) are allowed to sell no

more than 5% of the total number of shares of a firm within the second year and no more than 10%

in the second and third year combined. In addition, some firms promise a longer lockup period in

their reform plans, while some firms make further promises after the completion of the reform.

[Insert Table 1 here]

Table 1 summarizes the schedule of lockup expiration in the reform for our sample firms. We

check the lockup expiration for different periods, defined as follows: t refers to the reform

completion date, and [0, 6] is the first six months after reform completion (i.e., t to t+6). Other

periods are defined similarly. The last column (“Remaining”) stands for the percentage of shares

that are still locked up by the end of 2014. For each of the periods listed in the columns, we first

calculate, for each firm, the percentage of shares that are unlocked over the total nontradable

shares at the start of the reform and take an average across our sample firms.

Panel A of Table 1 shows the forecasted lockup expiration schedules, which are based on

data right after the completion date, taking into account both the requirements specified by the

CSRC guideline and additional promises made by firms. Panel B shows the actual lockup

expiration schedules. Data on both forecasted and actual lockup expiration are available from the

China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. Because some firms make

further promises, actual lockup expiration may take longer than forecasted, but the difference is

small. Though the lockup is required to be at least one year after the completion date, shares

transferred from nontradable shareholders to tradable shareholders as compensation become

tradable immediately after the completion date. On average, this accounts for 10.29% of all the

22

nontradable shares. Most lockups expire in the first three to four years, especially in the [31, 42]

period. After this period, for the median firm, all lockups have expired.

Several issues should be mentioned here. First, the reform may affect Chinese firms’

fundamentals (Campello, Ribas, and Wang, 2014; Liao, Liu, and Wang, 2014). However, if there

are any changes, both A- and B-shares are affected equally. Therefore, examining the change of

A/B share premium is largely unaffected by any change of firm fundamentals.20 Second, the

compensation is pure benefit transfer from the nontradable shareholders to the tradable

shareholders, and this should not have any direct effect on A-share valuation. Third, the

transferred shares in the compensation plan are immediately tradable after reform completion

date t3. Therefore, at t3, A-share float increases immediately, and there is also an expectation that

future A-share float will further increase due to lockup expirations.

5. Data and summary statistics

Our primary data source is the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR)

database, from which we collect the list of dual-listed A/B share companies, stock trading data

(e.g., stock price, returns, trading volume, total number of shares outstanding, and number of

tradable shares) and firm accounting data. CSMAR also provides detailed data on the reform,

including reform announcement date, completion date, compensation details, and also the

schedule of lockup expirations of nontradable shares. We also obtain intraday trading data from

CSMAR to calculate bid-ask spread.

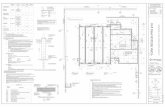

[Insert Figure 2 here] 20 It is possible that A-shareholders and B-shareholders have different portfolio holdings, and the change of A/B share fundamentals may change the risks faced by them in different ways. We investigate this directly in section 6.2; as a preview, we do not find significant change in systematic risks.

23

We start with all 90 A/B dual-listed firms. We exclude four firms that were delisted before

the reform, as well as another seven firms for which it took more than one year to complete the

reform.21 We also delete three firms that changed their foreign share listing from the B-share

market to the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.22 Our final sample includes 76 A/B share firms.

Among these firms, the earliest announcement of reform was made on October 10, 2005, and the

last announcement was made on December 30, 2006. The earliest completion date was

November 30, 2005, and the latest was August 27, 2007. Figure 2 presents the monthly

distribution of completion dates. A total of 69 firms completed their reforms by October 2006,

and the remaining seven firms completed their reforms in 2007.

We calculate A-share and B-share market index returns using individual stock trading data

from CSMAR. The A-share market return and the B-share market return are value-weighted

returns across all the A-share and B-share stocks, respectively. We use the market capitalization

of the tradable shares as the weights.23

[Insert Table 2 here]

Table 2 reports the summary statistics for our sample firms. We first sort all the firms into

two equal-sized groups based on the sample median ΔFloat and report the average characteristics

for the firms in each group. ΔFloat is defined as the total number of A-shares divided by the total

number of tradable A-shares. We also conduct a t test and Wilcoxon test on whether the

difference between the High ΔFloat and Low ΔFloat is significant. The average ΔFloat for the

Low ΔFloat group is 2.929, suggesting that in this group, on average, float increases by 192.9%.

21 We delete these seven firms because their event windows are significantly longer than those of other firms. However, our results on the long-term effects are robust if we include them in our sample. 22 These three firms are China International Marine Containers, Livzon Pharmaceutical Group, and China Vanke. They switched their foreign shares from the B-share market to the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2012, 2014, and 2014, respectively. Including them into our analysis and using their H-share price after they switched has very minimal effect on our results. 23 All the results are robust if we use total market capitalization as the weights.

24

For the High ΔFloat group, the average ΔFloat is 9.733, suggesting that, on average, float

increases by 873.3%. The average ΔFloat is large, and there is also a large cross-sectional

variation of ΔFloat.

We also compare several firm-level or share-level characteristics. Log(size) is the natural log

of total book assets measured at the previous fiscal year end before announcement. Dividend

payer is a dummy variable indicating that the firm has paid dividends in the year before the

reform. Premium is A/B share price premium and is equal to (Price of A-share)/(Price of B-

share), measured at the last trading day before the announcement. B-share prices are converted

into Chinese yuan using exchange rate from CSMAR. Volatility (A) and Volatility (B) are,

respectively, the return standard deviation of daily returns of A-shares and B-shares in the past

twelve months prior to the reform announcements, annualized by multiplying the square root of

252. Turnover (A) and Turnover (B) refer to the trading volume divided by the total number of

tradable shares in the past twelve months prior to the reform announcements. Spread (A) and

Spread (B) are, respectively, the proportional bid-ask spread of A-shares and B-shares,

calculated over the twelve months prior to the reform announcement. Volatility (A), Volatility

(B), Spread (A), and Turnover (B) are comparable to that of the U.S. or other developed markets

(Ang, Hodrick, Xing, and Zhang, 2009; Chordia and Swaminathan, 2000; Holden and Jacobsen,

2014), but Turnover (A) is significantly higher than that of the U.S., and Spread (B) is also

significantly higher than that of the U.S. Premium, Volatility (A), Turnover (A), and Spread (A)

are significantly correlated with ΔFloat, with High ΔFloat group having higher premium, higher

A-share volatility, higher A-share turnover, and lower A-share spread. These correlations are

consistent with our hypotheses. Other firm characteristics, including B-share volatility, turnover

and spread, are unrelated to ΔFloat.

25

6. Main results

6.1 ΔFloat and Change of premium

It is well documented that market level factors affect A/B share premium. Therefore, instead

of investigating the average time series change of premium, we investigate how premium

changes vary across firms with different changes in float: a difference-in-difference strategy.

We use the following model to test whether the demand curves are downward sloping and, if

so, how demand curves evolves in the long run.

ΔPremiumi,(t0, t3+N)= αN + βN ΔFloati + εi,(t0, t3+N), (1)

where i and t indicate firm and time, respectively. Premiumi is the A/B share price premium for

firm i and is equal to (Price of A-share)/(Price of B-share).24 B-share prices are converted into

Chinese yuan using exchange rate data from CSMAR. ΔPremiumi,(t0, t3+N) is the change of

premium from the announcement date t0 to N months after the completion date t3. We examine

various values of N from 0 to 72. Our results are significant at 5% level for all these N values.

For brevity, we only report the results when N=0, 1, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72. We also

investigate a specification where ΔPremiumi,(t0, t3+N) is defined as the change of premium from t0

to December 2014, the end of our sample period. Different firms have different completion dates.

The length from the completion date to December 2014 varies from seven to nine years. ΔFloati

is the total number of A-shares divided by the total number of nontradable A-shares, measured

before the reform announcement (t0). It captures the expected increase of A-share float. If

demand curves are downward sloping, we expect βN to be negative. If demand curves are less

24 Fernald and Rogers (2002) document that premium is affected by market-level factors. Our results are robust if we examine market-adjusted premium which is defined as premium minus the average premium of all firms except the subject firm.

26

downward sloping in the long term than in the short term, we expect the magnitude (i.e., the

absolute value) of βN to decrease when N increases.

[Insert Table 3 here]

Table 3 reports the results. For the nine different horizons, βN is statistically significant at the

1% level, except in the case of N=1, where it is significant at the 5% level. β0 is -0.0277,

suggesting that a 100% increase in A-share float decreases the A/B share premium by 2.77%. β1

is -0.0264, which is similar to β0. The absolute magnitude of βN increases to -0.0680 when N=12

and further increases to -0.786 when N=24. Afterwards, the absolute magnitude of βN starts to

decrease monotonically. The largest decrease of the absolute magnitude of βN happens from

when N=24 to when N=48. After that, βN continues to decrease but very slowly. In December

2014, βN is -0.0349. The decrease of βN from N=48 to December 2014 is not statistically

significant.

The initial increase of the absolute magnitude of βN may be related to the fact that

nontradable shares have a lockup period. As shown in Table 1 and discussed in Section 4.2, it

takes two to three years, on average, for most of the nontradable shares to float. Liao, Liu, and

Wang (2011) find that, on average, stock prices decrease around lockup expiration days, even

though lockup expirations are scheduled well in advance, suggesting that short-term demand

curves are downward sloping even when supply increase is expected.25 The initial increase of the

absolute magnitude of βN may be an outcome of cumulative realized increases of float. The

lockup expiration schedule matches the time series evolvement of βN, except that the absolute

magnitude of βN is the largest at N=24, but the nontradable shares lockup expirations concentrate

in the t+31 to t+42 period. One possible reason for this is that shares that are allowed to float

25 This is not unique to China. IPO lockup expirations are known ex ante. Field and Hanka (2001) find stock price drops by 1.5% around the IPO lockup expiration days in the U.S.

27

only after the second year are mainly held by strategic shareholders who have more than 5%

ownership. These shareholders are less likely to sell, especially given that part of their shares

already become floatable in the first two years.

[Insert Figure 3 here]

In Figure 3, we plot the average premium for two groups of firms by ΔFloat: one group of

firms with ΔFloat above the sample median and the other group of firms with ΔFloat below the

sample median, from six months before the announcement date (t0) to 84 months after the

completion date (t3). Before the announcement, the average premium of the high ΔFloat group is

around 0.70 higher than that of the low ΔFloat group, consistent with the hypothesis that the

scarcity of shares leads to high price. The difference shows no detectable change from t0-6 to t0.

Right after the completion date, the difference between these two groups drops to 0.37. The

difference reaches the lowest at t3+17 when it is 0.00. The difference is 0.27 at t3+84, still

significantly lower than its pre-reform level.26

[Insert Figure 4 here]

Our sample is relatively small. To make sure that our results are not driven by outliers, in

Figure 4 we virtualize each of the nine cross sections in Table 3 by scatter plotting the data.

There is a clear inverse relationship between ΔFloat and ΔPremium for all the nine horizons. We

also find that there are a few very large ΔFloat values. If we exclude the four firms whose ΔFloat

is larger than 15, the inverse relation becomes even stronger.

One concern is that premium of high ΔFloat firms would have reduced more than low ΔFloat

firms even in the absence of the Split-Share Structure Reform. One possibility is that China has

26 The average premium for both groups shows strong time series variations which may not be related to the supply changes. For example, the premium is lowest two to three months after the reform and is highest around 36 months after the reform. This is because in this period the China’s A-share market had a big boom while the B-share market price increased less.

28

been undertaking economic reforms toward a more business-friendly economy over the last 30

years. If this benefits more for B-shares investors of higher ΔFloat firms, in the long run, we may

also observe a relatively larger reduction of premium for firms with higher ΔFloat. Although we

cannot rule out this possibility completely, we provide two sets of evidence inconsistent with this

interpretation. First, as we can see from Figure 3, after the first 36 “turbulent” months, the

premium of high ΔFloat and low ΔFloat firms moves together. If anything, high ΔFloat firms’

premium becomes slightly larger (though not statistically significant) relative to low ΔFloat

firms. Second, we conduct a placebo test by assigning fake reform completion dates for all the

firms back to December 31, 1996. Coincidentally, from December 31, 1996 to December 31,

2004, the average premium across all the A/B share firms decreased by around 0.50 which is

very similar to the average premium decrease in main sample period (Figure 3). If we regress the

change of premium from the fake completion date to December 31, 2004 (which is the last

December before the reform started) on ΔFloat, we find that the coefficient of ΔFloat is 0.002

with a t-value of 0.14. Both tests show that there is no evidence that different ΔFloat firms’

premium changes differently in the long run, in the absence of the Split-Share Structure Reform.

Overall, these results provide support for our Hypothesis 1 that demand curves are downward

sloping, even up to around ten years after the supply shocks.

6.2 Additional tests

Even though firms do not have the flexibility to select whether to participate in the Split-

Share Structure Reform and ΔFloat is decided long time before the reform, firms with different

ΔFloat may still be different. In this section, we provide further evidence supporting our

hypothesis and rule out alternative interpretations.

29

6.2.1 ΔFloat and the change of systematic risks

A-share investors and B-share investors face different investment opportunities: A-share

investors mainly invest in China, and B-share investors mainly invest outside of China. Even

though A-shares and B-shares have the same fundamentals, they may contribute different risks to

their investors’ portfolios. In Panel A of Table 4, we examine whether the reform changes A-

shares’ and B-shares’ systematic risks, and, if so, whether the change of systematic risks are

related to ΔFloat in a way that can potentially explain the change in A/B share premium.

[Insert Table 1 here]

We measure A-shares’ systematic risk using Beta (A, A-index) which is calculated as

covariance between A-share return and A-share market return divided by the variance of A-share

market return. We calculate two beta variables for B-shares: Beta (B, B-index) and Beta (B,

MSCI). The definitions of these two beta variables are similar to Beta (A, A-index). B-index

return is calculated across all the B-shares. The MSCI index is the MSCI World index, which is

widely used as a common benchmark for global stock returns. Beta (B, B-index) is more relevant

to investors whose investment is concentrated in the B-share market, and Beta (B, MSCI) is

more relevant to investors whose investment is diversified globally.27 The results from Panel A

of Table 4 show no evidence that the change of these three systematic risk measures is

significantly related to ΔFloat, ruling out the possibility that the negative relationship between

premium change and ΔFloat is a reflection of change of systematic risks.

27 Those risk measures are similar to the ones used by Mei, Scheinkman, and Xiong (2009).

30

6.2.2 ΔFloat and the change of liquidity

Change of float may change liquidity. Searching models predict that matching between

buyers and sellers is easier when float is higher (Duffie, Garleanu, and Pedersen, 2005; Vayanos

and Wang, 2007; and Weill, 2008). In these models, illiquidity is negatively correlated with float.

In Panel B of Table 4, we find that ΔFloat is indeed negatively correlated with change of

illiquidity. We measure illiquidity by proportional bid-ask spread. The results show that A-share

spread decrease is negatively correlated with ΔFloat and is significant (though mostly marginally

so) at the 10% level for six out of the eight horizons. However, there is no evidence that ΔFloat

is significantly correlated with B-share spread change.

It is known that liquidity is positively correlated with stock prices (Amihud and Mendelson,

1986). Keeping other factors unchanged, decrease of A-share spread should increase A-share

price. Therefore, liquidity change predicts that A-share price should increase more for firms with

high ΔFloat. Our finding is opposite to this prediction, suggesting that the demand curve effect

dominates the liquidity effect.

6.2.3 ΔFloat and the change of corporate governance

Another concern is from the corporate governance perspective. The main purpose of the

reform was to align the incentives of the small tradable shareholders and the controlling

nontradable shareholders (Liao, Liu, and Wang, 2014). It has also been shown that foreign

investors care more about corporate governance than domestic investors do (Leuz, Lins, and

Warnock, 2010). If this is also true for A- and B-share investors, and if corporate governance

improves as a result of the reform, we should expect that B-share prices increase more than A-

shares, leading to a reduction of A/B share premium. If corporate governance improves more for

31

the firms with higher ΔFloat, we should expect that A/B share premium will decrease more for

those with higher ΔFloat than for those with lower ΔFloat. This interpretation is also consistent

with our findings in Table 3.

This corporate-governance-based explanation predicts that, in the short-term period event

around the reform, both A-share prices and B-share prices should increase and B-share prices

should increase more than A-share prices. However, the demand-curve-based explanation

predicts that A-share prices should decrease and B-share prices should stay unchanged.

Empirically, we find that, on average in the reform period, A-share price decreases by 22.61%

relative to the contemporaneous A-share market index, with a value of -6.87, which is

statistically significant. However, B-share price increases by 1.99% relative to the

contemporaneous B-share market index with a t value of 1.02, which is statistically

insignificant.28 In the cross section, we also find that ΔFloat is negatively correlated with A-

share abnormal return but insignificantly correlated with B-share abnormal return. If we regress

A-share abnormal return around the reform period on ΔFloat, the coefficient of ΔFloat is -0.0122

with a t value of -2.01. However, if we regress B-share abnormal return around the reform period

on ΔFloat, the coefficient of ΔFloat is -0.0015 with a t value of -0.40. These results are

inconsistent with the prediction of the corporate-governance-based interpretation but consistent

with the demand-curve-based interpretation.

We also examined how ΔFloat is related to A-share and B-share abnormal returns for longer

horizons. We regress A-share abnormal returns or B-share abnormal returns on ΔFloat. The

coefficient of ΔFloat is never statistically significant when the dependent variable is B-share

abnormal returns. It is statistically significant when the dependent variable is A-share abnormal

28 There are 24 B-shares that do not have A-shares. They do not conduct the Split-Share Structure Reform. Even if we use them as a benchmark, we find similar results.

32

returns for horizons up to 24 months. The statistical significance disappears for longer horizons,

which echoes the weakness of the long-run event study on returns we discussed in the

introduction. Our method on examining change of premium circumvents this weakness and is

able to detect the long-term effect with statistical power.

6.2.4 The heterogeneity of nontradable shareholders

Another alternative explanation is related to the fact that significant fraction of the

nontradable shares is owned by the government and controlling shareholders. The existence of

the government as a shareholder may lead to more government subsidies or bail-out when a firm

runs into distress. The existence of controlling shareholders may also benefit the firm. If

domestic A-shareholders are more likely to enjoy these benefits than foreign B-shareholders or it

is perceived to be so, A-share price can react more negatively than B-share price in anticipation

that state shareholders or controlling shareholders may sell their holding. We investigate this by

examining whether different types of nontradable shares have different effects.

66% of the nontradable shares are owned by the government (stated-owned shares). The

remaining one third is virtually all owned by other non-state-owned firms (i.e., legal persons).

We also classify investors into large nontradable shareholders and small nontradable

shareholders. Large nontradable shareholders are those with more than 5% ownership, and small

nontradable shareholders and the ones with less than 5% ownership. On average, large

nontradable shareholders own 81% of all the nontradable shares. We define four different change

of float variables: (1) ∆ : number of state-owned nontradable shares divided by number

of tradable shares; (2) ∆ : number of non-state-owned nontradable shares divided

by number of tradable shares; (3) ∆ : number of nontradable shares owned by

33

shareholders with more than 5% ownership divided by number of tradable shares; (4)

∆ : number of nontradable shares owned by shareholders with less than 5% ownership

divided by number of tradable shares. Across firms, ∆ is slightly negatively correlated

with ∆ , with a correlation coefficient of -0.08 and a p-value of 0.50; ∆

and ∆ is slightly positively correlated with a correlation coefficient of 0.15 and a p-

value of 0.20. ∆ and ∆ are highly correlated, with a correlation coefficient

of 0.88 and a p-value less than 0.001. ∆ and ∆ are also highly positively

correlated with a correlation coefficient of 0.54 and a p-value less than 0.001. This suggests that

state shareholders own large blocks, while non-state legal persons tend to have a small

ownership.

[Insert Table 5 here]

Table 5 reports the results. The results show that both ∆ and ∆ have

long-run effect on A/B share premium. In terms of the statistical significance, the effect of

∆ is more stable and is statistically significant at 5% level for all the nine horizons

reported in Table 6. The absolute value of the coefficients of ∆ is similar to that of

∆ , suggesting that one unit of non-state-owned shares have similar price impact than

one unit of state-owned shares. Given the high correlation between∆ and ∆

and high correlation between ∆ and ∆ , not surprisingly, the results

based on ∆ and ∆ are similar.

Overall, these results suggest that both large state-owned shares and small legal person shares

have long-run effect on A/B share premium. This is inconsistent with the alternative explanation

outlined at the beginning of this section. There is another related alternative explanation which

34

we cannot completely rule out: A-shareholders prefer to having higher nontradable shareholders

ownership (regardless of their identity), while B-shareholders are neutral about the fraction of

nontradable shares. This argument cannot explain why the effect of ΔFloat on A/B share

premium change is the largest two to three years after the reform, but otherwise is

observationally equivalent to what we document. However, we do not think this is a plausible

alternative explanation because the original motive to do the Split-Share Structure Reform was to

mitigate the conflict of interests between tradable and nontradable shareholders. Scholars do find

that the reform benefited the reformed firms (Campello, Ribas, and Wang, 2014). In Section 7,

we provide further evidence supporting the demand-curve-based interpretation by testing other

hypotheses outlined in Section 3.

6.2.5 Reforms may be partially expected

The first announcement of the pilot program was on April 29, 2005. At that time, however,

there was still a real concern that the reform might not be successful. After the first two batches,

which were considered a success, the program expanded to all the firms.

In the previous empirical analysis, we calculated the change of premium from the

announcement of the start of the reform (t0) for a firm to the announcement of its completion (t3).

The window is firm-specific. Based on the above analysis, it is likely that the reform, especially

for the firms not in the trial batches, was partially expected. If so, it is likely that price at t0

already reflects the reform, though with uncertainty regarding when the reform will begin as well

as uncertainty regarding the compensation package.

The fact that reforms may be partially expected may lead to biased estimation (Hennessy and

Strebulaev, 2015). Before the reform, tradable A-shareholders may expect that they will receive

35

compensation from nontradable shareholders. The embedded rights may reflect into A-share

prices. Given that B-shareholders will not receive any compensation, in this special period, one

share of tradable A-share does not have the same rights as one B-share. If A-shareholders indeed

expect this, A-share price should increase more than B –share price in anticipation of the reform

and will drop more than B-share at the reform completion date (which is also the ex-rights date),

and the change of premium from t0 to t3 may partially reflect the effect of embedded rights. If

investors also expect that the compensation is positively correlated with ΔFloat, our estimation

in Table 3 can be biased. There is little evidence, as we can see from Figure 3, that A/B share

premium change is related to ΔFloat in the six months before announcement. In Section 8, we

find that the compensation tradable shareholders received is too insensitive to ΔFloat to explain

the effect of ΔFloat on A/B share premium.

[Insert Table 6 here]

To further mitigate this concern, we re-run equation (1) by setting t0 to earlier days for all

firms. Allowing nontradable shareholders to compensate tradable shareholders is the key

innovation of the Split-Share Structure Reform comparing to the other two failed trials in 1999

and 2001. Before the reform details were layout, there was little anticipation that tradable

shareholders will receive any compensation. We choose August 15, 2005 as a “pre-event date”.

This is because the two official documents governing the operational procedures of the Split-

Share Structure Reform were soon to be issued: Guidance Notes on the Split Share Structure

Reform of Listed Companies was issued on August 23, 2005, and Administrative Measures on

the Split Share Structure Reform of Listed Companies was issued on September 4, 2005. The two

documents started the full-scale reform. Our results are similar if we set t0 to be May 31, 2005

when the second trial was announced or March 31, 2005 which is before the first trial was

36

announced. Panel A of Table 5 reports the results. Comparing these results to those presented

Table 3, the absolute magnitude of the coefficients of ΔFloat actually increases slightly. Overall,

however, the results are similar.

In another test, we link the change of premium in the December 1999 failed trial period to the

change of premium around the Split-Share Structure Reform. On December 2, 1999, the CSRC

hand-picked ten listed companies to pilot the nontradable shares’ sales. Sales price were set

using firms’ average earnings per share in the past three years multiplied by ten. Sales were

quickly suspended in 25 days after two companies practiced this and the stock market dropped

by more than 7%. If the A/B share premium change in this period and the Split-Share Structure

Reform period is driven by the same concern on downward sloping demand curve, we should

expect that the change of premium in both periods is positively correlated. Since there is no

compensation arrangement in the 1999 trial, firms’ change of premium in December 1999 is not

contaminated by anticipation of receiving compensation. We replace ΔFloat in equation (1) by

change of premium from December 1, 1999 to December 31, 1999. We find that the coefficient

of change of premium from December 1, 1999 to December 31, 1999 ranges from 0.256 to 0.458,

and are statistically significant at 5% level except when N=24 where the coefficient is 0.275 and

t-value is 1.47.29 This provides further evidence that the results in Table 3 are not driven by the

fact that reforms may be partially expected.

29 We also link the premium change in the second failed trial period to the change of premium in the split-share structure reform period. The second failed trial started in June 2001 and was withdrawn in June 2002. We do not find any statistical significance here, maybe because the 2001-2002 trial lasted for too long and the change of premium in that period is too noisy.

37

6.2.6 Aligning the windows

There are two other concerns. First, in the previous section, we set t0 to August 15, 2005, but

each firm still has its own completion date. This means that the change of premium is calculated

over different windows. A/B share premiums are affected by market-level factors (Fernald and

Rogers, 2002). In the previous regressions, we did not control for market level factors. Second,

the starting date and the completion date of reforms may be endogenously chosen by firms, and

their choice may be related to ΔFloat as well as to premium change.

In order to exclude these two possibilities, in this section, we align the windows across all the

firms by setting t0 to August 15, 2005, and t3 to December 31, 2007, for all the firms. By

December 2007, all of our firms have completed their reforms. In this specification, market-level

factors are automatically controlled, because changes of premiums are calculated over the same

period. In addition, in this specification, we avoid using firms’ own announcement date or

completion date, and hence we also avoid the possible endogeneity of the timing of reform.

Panel B of Table 5 reports the results. For the last column, the results are exactly the same as

those in the last column in Panel A, because premium change is calculated over the same period.

Results in other columns are different from the results in Panel A. Noticeably, the coefficients of

ΔFloat for the first two columns are different. In Table 3 and Panel A of Table 5, the coefficients

of ΔFloat show an inverse U-shape when horizon increases. However, in Panel B of Table 5, the

coefficients decrease almost monotonically when the horizon increases. This is because

horizon=0 in Panel B is December 2007. As shown in Figure 2, most firms completed their

reforms before October 2006. On average, 18 months elapse from reform completion to

December 2007. Therefore, horizon=0 in Panel B of Table 5 is roughly between horizon=12 and

horizon=24 in Table 3. Therefore, results in both Tables show that the absolute magnitude of

38

ΔFloat is highest in the second year after completion. Overall, the results in Panel B of Table 5