Diverse habitat use during two life Bahama Oriole ......Socialinteractions During the aforementioned...

Transcript of Diverse habitat use during two life Bahama Oriole ......Socialinteractions During the aforementioned...

Submitted 6 February 2017Accepted 3 June 2017Published 22 June 2017

Corresponding authorMelissa R Pricemelrpricegmailcom

Academic editorDonald Kramer

Additional Information andDeclarations can be found onpage 14

DOI 107717peerj3500

Copyright2017 Price and Hayes

Distributed underCreative Commons CC-BY 40

OPEN ACCESS

Diverse habitat use during two lifestages of the critically endangeredBahama Oriole (Icterus northropi)community structure foraging and socialinteractionsMelissa R Price1 and William K Hayes2

1Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Management University of Hawailsquoi at ManoaHonolulu HI United States of America

2Department of Earth and Biological Sciences Loma Linda University Loma Linda CAUnited States of America

ABSTRACTOur ability to prevent extinction in declining populations often depends on effectivemanagement of habitats that are disturbed through wildfire logging agriculture ordevelopment In these disturbed landscapes the juxtaposition of multiple habitattypes can be especially important to fledglings and young birds which may leavebreeding grounds in human-altered habitat for different habitats nearby that provideincreased foraging opportunities reduced competition and higher protection frompredators In this study we evaluated the importance of three habitat types to two lifestages of the critically endangered Bahama Oriole (Icterus northropi) a synanthropicsongbird endemic to Andros The Bahamas First we determined the avian speciescomposition and relative abundance of I northropi among three major vegetation typeson Andros Caribbean pine (Pinus caribaea) forest coppice (broadleaf dry forest) andanthropogenic areas dominated by nonnative vegetation (farmland and developedland) We then compared the foraging strategies and social interactions of two ageclasses of adult Bahama Orioles in relation to differential habitat use Bird surveyslate in the Bahama Oriolersquos breeding season indicated the number of avian speciesand Bahama Oriole density were highest in coppice Some bird species occurring inthe coppice and pine forest were never observed in agricultural or residential areasand may be at risk if human disturbance of pine forest and coppice increases as isoccurring at a rapid pace on Andros During the breeding season second-year (SY)adult Bahama Orioles foraged in all vegetation types whereas after-second-year (ASY)adults were observed foraging only in anthropogenic areas where the species nestedlargely in introduced coconut palms (Cocos nucifera) Additionally SY adults foragingin anthropogenic areas were often observed with an ASY adult suggesting divergenthabitat use for younger unpaired birds Other aspects of foraging (vegetation featuresfood-gleaning behavior and food items) were similar for the two age classes OlderBahama Orioles exhibited relatively higher rates of social interactions (intraspecificand interspecific pooled) in anthropogenic areas and won more interaction outcomescompared to younger adults Our findings concur with those of other studies indicatingdry broadleaf forest is vitally important to migrating wintering and resident birds

How to cite this article Price and Hayes (2017) Diverse habitat use during two life stages of the critically endangered Bahama Oriole(Icterus northropi) community structure foraging and social interactions PeerJ 5e3500 DOI 107717peerj3500

including the critically endangered Bahama Oriole which appears to depend heavilyon this vegetation type during certain life stages

Subjects Animal Behavior Ecology ZoologyKeywords Caribbean Dry tropical forest Synanthropic species Anthropogenic habitat Pineforest Delayed plumage maturation

INTRODUCTIONConservation of endangered species often depends on effective management withinhuman-modified landscapes (Gardner et al 2009) Resource subsidies in anthropogenicareas such as cultivated plants or discarded food items influence avian distributionabundance and productivity (Faeth et al 2005) Synanthropic species which affiliate withhumans often increase in disturbed areas (Kamp et al 2009 Coulombe Kesler amp Gouni2011) whereas other species including many Nearctic-Neotropical migrants may avoidsuch areas or decline following disturbance (Miller et al 2007) particularly where muchof the canopy is removed (Norris Chamberlain amp Twedt 2009)

Some species may be negatively affected by expanding agriculture and development ifmultiple habitat types are required to sustain viable populations (Cohen amp Lindell 2005)The juxtaposition of multiple habitat types can be especially important to fledglings andyoung birds whichmay leave breeding grounds in human-altered habitat for different habi-tats nearby that provide increased foraging opportunities and higher protection frompreda-tors (Cohen amp Lindell 2004Ausprey amp Rodewald 2011Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) Juvenilesare often less efficient foragers than adult birds (Wunderle 1991 Heise amp Moore 2003Gall Hough amp Fernaacutendez-Juricic 2013) and may seek habitats with reduced competitionfrom conspecifics To effectively target conservation efforts we must therefore understandthe relative contribution of each habitat type to each life stage and by extension populationstability (Dent amp Wright 2009)

The Bahama Oriole (Icterus northropi) a critically endangered island endemic extirpatedfrom Abaco Island the Bahamas in the late 20th century and remaining today only onAndros Island the Bahamas has contended with profound habitat changes since thearrival of humankind (Steadman et al 2015 Steadman amp Franklin 2015) While loggingand human development removed native breeding and foraging habitats (Currie et al2005) and potentially impacted species sensitive to roads and clearings (Laurance Goosemamp Laurance 2009) humans provided novel opportunities for feeding and nesting in theform of introduced plant species (Nickrent Eshbaugh amp Wilson 1988) Coconut palms(Cocos nucifera) for example were imported to the region by humans about 500 years ago(Child 1974 Baudouin amp Lebrun 2009) and have become the Bahama Oriolersquos favorednesting habitat (Allen 1890 Baltz 1996 Baltz 1997) most likely due to a preference forthe tallest trees available within a nest-site (Price Lee amp Hayes 2011)

Although largely a synanthropic species associated with human-altered landscapesduring the breeding season (Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) the BahamaOriole like other species(Vega Rivera Rappole amp Haas 1998 Graham 2001) may still depend on other vegetation

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 219

types to sustain various activities throughout its life cycle and may benefit from foraging inmultiple vegetation types (Cohen amp Lindell 2005) including dry tropical forest (coppice)pine forest and human-altered (anthropogenic) areas Dry tropical forest comprises one ofthe most endangered tropical ecosystems globally due to anthropogenic disturbance(Janzen 1988 Gillespie et al 2012 Banda et al 2016) In the Bahamas dry tropicalbroadleaf forest (coppice) decreased due to the effects of forest fires on ecological successionand forest clearing in themid-1900s but has largely recovered since thenHowevermuch ofwhat remains lacks protection and the secondary forest lacks heterogeneity (Myers Wadeamp Bergh 2004Currie et al 2005) butmay still be an important contributor to avian speciesdiversity (Dent amp Wright 2009) Recently coppice loss has accelerated due to developmentincreased frequency of human-caused fires and invasion by non-native vegetation duringsuccession (Smith amp Vankat 1992 Myers Wade amp Bergh 2004 Koptur William amp Olive2010 Thurston 2010 Carey et al 2014 see also Larkin et al 2012)

Because interspecific and intraspecific interactions can be influenced by habitatdistribution and foraging strategies (Mac Nally amp Timewell 2005 Shochat et al 2010)we needed a better understanding of the avian community structure in habitats used bythe Bahama Oriole Thus we began by determining the avian species composition andrelative abundance of the Bahama Oriole among three major vegetation types on AndrosCaribbean pine forest coppice and anthropogenic areas

Next we sought to better understand the importance of these three vegetation types totwo life stages of the Bahama Oriole In Bahama Orioles both males and females in theirsecond year of life though reproductively viable (Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) display plumagecoloration similar to immature birds a trait referred to as delayed plumage maturationThis trait though common in males of many species is not a common characteristicin females (Bentz amp Siefferman 2013) and may contribute to reduced aggression fromolder birds (VanderWerf amp Freed 2003) reduced predation risk (Lyu Lloyd amp Sun 2015)and increased overwinter survival (Berggren Armstrong amp Lewis 2004) A previous studysuggested that pine forests and coppice may be particularly important for young BahamaOrioles (Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) Thus in the next phase of our study we comparedthe foraging strategies and social interactions (both intraspecific and interspecific) of twoage classes of adult Bahama Orioles second-year adults and after-second-year adults inrelation to differential habitat use

METHODSStudy areaAndros Island The Bahamas is divided by bights up to 5 km wide into three mainhuman-occupied cays (North Andros Mangrove Cay South Andros) and many smalleruninhabited cays (Fig 1) Andros Island is dominated on the eastern portion by extensiveCaribbean pine forest with coppice (dry broadleaf forest) at higher elevations and inpatches interspersed within the pine forest Mangrove associated with vast tidal wetlandsand accessible only by boat dominates the western half The pine forest was heavily

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 319

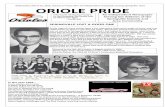

Figure 1 Andros Island is divided into three large inhabited cays (North Andros Mangrove CaySouth Andros) andmany smaller uninhabited cays by channels up to 5 km acrossMap data EsriDigital Globe GeoEye Earthstar Geographics CNESAirbus DS USDA USGS AeroGRID IGN GISUser Community

logged in the mid-1900s (Myers Wade amp Bergh 2004) and old logging roads providethe only ground access to the interior Pine trees in the secondary forest are slender andclosely spaced with an understory of poisonwood (Metopium toxiferum) and palmetto(Sabal palmetto) fern or shrub (Currie et al 2005) Human settlements and agriculturaldevelopments are spread along the eastern portion of the island

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 419

Population surveys and observational effortOther studies have assessed bird composition on Andros during the winter (Currie etal 2005) and early breeding seasons (Lloyd amp Slater 2010 Price Lee amp Hayes 2011)To evaluate population density and species composition late in the Bahama Oriolersquosbreeding season we conducted line transects between 5ndash18 July 2005 in coppice pineforest and anthropogenic areas on North Andros using methods similar to Emlen (1971)Emlen (1977) and Hayes et al (2004) During this time period we expected some BahamaOriole chicks would have fledged while others were initiating second broods We walkedindividually or with an assistant at approximately 1 kmh surveying 33 transects totaling195 km with 13 surveys in coppice (98 km) 10 surveys in pine forest (24 km) and 10surveys in anthropogenic areas (73 km) Each habitat type was variable and we sampledacross the range of variability Coppice (dry broadleaf habitat) ranged from 2 m to 10m in height Pine forest survey sites included forest with an understory of poisonwood(Metopium toxiferum) and palmetto (Sabal palmetto) fern or shrub and at least one areathat had not been previously logged (primary forest) Anthropogenic areas included landswith low-density houses stores and other buildings as well as agricultural cleared landswith nearby residential dwellings We recorded all birds identified by sight or vocalizationto compare relative and habitat-specific abundance of Bahama Orioles with other speciesResearch was approved by the Loma Linda University Institutional Animal Care andUse Committee (Protocol 8120010) and conducted under a Bahamas Ministry of theEnvironment Research Permit

Foraging behaviorWe recorded foraging and social interaction data from 17 June to 13 July 2007 and 29Marchto 30 May 2009 Total time in direct observation of Bahama Orioles was approximately122 h To quantify foraging behaviors we conducted continuous focal observations ofindividuals for up to 2 h or until the bird flew out of sight We recorded the first behaviorobserved after 10-min intervals or the first behavior after a location change gt10 mwhichever came first Because foraging birds were often only within eyesight for briefperiods of time resulting in single foraging data points for many birds we includedonly the first foraging behavior per bird per day in calculations for statistical analysesWe noted age of the bird as second-year (SY) or after-second-year (ASY) based onplumage coloration (Garrido Wiley amp Kirkconnell 2005) and recorded foraging variablesper Remsen amp Robinson (1990) including habitat foraged in location of the bird substratefed upon and food identity As one cannot distinguish Bahama Orioles males and femalesby color or behavior we did not note the sex of the individual We also noted foliage speciesin which foraging occurred and location of the bird in the vegetation both horizontally(by dividing the tree into visual thirds of inner middle outer) and vertically (using aclinometer) Substrates used during foraging were recorded as air flowers berries leavestwigs ground or bark Foraging tactics were identified as perch gleaning (picking foodfrom a nearby substrate while perched) hang gleaning (picking food from a substrate whilehanging upside down) or air-gleaning (plucking insects from the air) We recorded thetype of food eaten if it could be identified

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 519

Social interactionsDuring the aforementioned focal observations all intraspecific and interspecificinteractions were also noted per Bowman et al (1999) as an aerial chase tree chaselunge or usurp The species and sex (if they could be determined) of the birds were notedas well as the directionality of each interaction and outcome of the interaction such aswhether each bird flew away or remained

Statistical analysesWe used both parametric and non-parametric tests (Zar 1996) depending on the nature ofthe dependentmeasure and whether or not assumptions weremetWe compared the distri-bution of individual bird species among the three habitats using Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAsWe compared foraging variables and social interactions between SY and ASY adult BahamaOrioles using chi-square tests for categorical data and independent-samples t -tests forcontinuous data with habitat categories collapsed to lsquolsquoanthropogenic habitatrsquorsquo and lsquolsquonotanthropogenic habitatrsquorsquo and data from 2007 and 2009 combined due to statistical similarity

We also computed effect sizes which are largely independent of sample size (in contrastto statistical significance) and more readily compared among different data sets anddifferent studies (Nakagawa amp Cuthill 2007) For Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAs we calculatedeta-squared (η2) as χ2N minus1 (Green amp Salkind 2005) with values of sim001 sim006 andge014 loosely considered smallmedium and large respectively (Cohen 1988) For pairwisecomparisons (t -tests) we relied on Cohenrsquos d using Hedgesrsquos pooled standard deviation(Nakagawa amp Cuthill 2007) withsim01sim05 andge 08 deemed smallmoderate and largerespectively (Cohen 1988) For tests of proportions (χ2) we computed Phi (ϕ) for 2times2 andCramerrsquos V for larger contingency tables with sim01 sim03 and ge05 considered smallmoderate and large (Cohen 1988) Following Nakagawa (2004) we chose not to adjustalpha for multiple tests Although some chi-square tests did not meet assumptions ofminimal expected frequencies the effect sizes corresponded well with and supported the in-terpretations of significance All analyses were performed using SPSS 170 (2008) with alphaof 005 Values are presented as mean plusmn 1 SE Rarefaction analyses to determine the likelynumber of species per vegetation type were performed using EstimateS with 1000 runs

RESULTSPopulation densitiesThe number of avian species detected late in the reproductive season (July) was higher incoppice (34) and roughly equivalent in pine forest (24) and anthropogenic habitat (26)(Table 1) The potential number of species in each habitat at the 95 confidence intervalwas calculated as 35ndash52 in coppice 27ndash40 in pine forest and 26ndash40 in anthropogenichabitat Some species clearly associated with one or two habitats whereas otherswere generalists however transects with zero counts limited statistical power and ourability to identify possible habitat preferences for a number of species including theBahama Oriole (P = 018 η2 = 011 note moderately large effect size) ASY and SYBahama Orioles were most numerous in coppice (56km) followed by anthropogenic

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 619

Table 1 Relative density by habitat (individualskm) of birds on North Andros The Bahamas from 33 line transects during June and July of2005 with KruskalndashWallis ANOVA results (Chi-square and P values) and eta-squared (η2) effect sizes

Species Pine Coppice Anthropogenic χ22 P η2

X plusmnSE X plusmnSE X plusmnSE

American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) 00 00 09plusmn 08 394 014 012Bahama Mockingbird (Mimus gundlachii) 14plusmn 08 44plusmn 23 00 689 0032 022Bahama Oriole (Icterus northropi) 00 56plusmn 44 12plusmn 06 344 018 011Bahama Swallow (Tachycineta cyaneoviridis) 05plusmn 04 20plusmn 12 15plusmn 11 092 063 003Bahama Woodstar (Calliphlox evelynae) 00 02plusmn 02 01plusmn 01 174 042 005Bahama Yellowthroat (Geothlypis rostrata) 02plusmn 02 12plusmn 06 00 683 0033 021Bananaquit (Coereba flaveola) 24plusmn 08 11plusmn 08 29plusmn 09 424 012 013Black-and-white Warblera (Mniotilta varia) 00 02plusmn 02 00 167 044 005Black-faced Grassquit (Tiaris bicolor) 154plusmn 46 55plusmn 23 03plusmn 02 1305 0001 041Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea) 102plusmn 25 46plusmn 24 11plusmn 09 1056 0005 033Black-whiskered Vireo (Vireo altiloquus) 83plusmn 26 125plusmn 42 25plusmn 10 381 015 012Common Ground-Dove (Columbina passerine) 21plusmn 11 22plusmn 10 54plusmn 22 293 023 009Cuban Pewee (Contopus caribaeus) 06plusmn 06 02plusmn 01 00 297 023 009Cuban Emerald (Chlorostilbon ricordii) 13plusmn 11 53plusmn 26 51plusmn 14 648 0039 020Eurasian Collared-Doveb (Streptopelia decaocto) 08plusmn 06 15plusmn 09 72plusmn 37 559 006 017Gray Kingbird (Tyrannus dominensis) 24plusmn 17 55plusmn 45 50plusmn 17 600 0050 019Great Lizard-Cuckoo (Saurothera merlini) 00 02plusmn 01 03plusmn 03 153 047 005Greater Antillean Bullfinch (Loxigilla violacea) 60plusmn 30 04plusmn 04 00 820 0017 026Hairy Woodpecker (Picoides villosus) 42plusmn 20 32plusmn 16 01plusmn 01 574 006 018House Sparrowb (Passer domesticus) 00 17plusmn 17 05plusmn 05 081 067 003Key West Quail-Dove (Geotrygon chrysie) 00 08plusmn 08 00 344 018 011Killdeer (Charadrius vociferous) 00 00 11plusmn 09 394 014 012La Sagrarsquos Flycatcher (Myiarchus sagrae) 08plusmn 07 14plusmn 07 00 409 013 013Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla) 00 13plusmn 11 30plusmn 10 1017 0006 032Loggerhead Kingbird (Tyrannus caudifasciatus) 00 00 00 000 100 000Mangrove Cuckoo (Coccyzus minor) 00 11plusmn 11 00 167 044 005Northern Bobwhiteb (Colinus virginianus) 23plusmn 13 04plusmn 03 00 435 011 014Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) 09plusmn 07 22plusmn 22 73plusmn 18 1534 0001 048Pine Warbler (Setophaga pinus) 26plusmn 11 05plusmn 04 00 688 0032 022Red-legged Thrush (Turdus plumbeus) 12plusmn 06 19plusmn 08 00 576 006 018Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) 00 17plusmn 17 01plusmn 01 081 067 003Rock Pigeonb (Columba livia) 02plusmn 02 03plusmn 03 22plusmn 21 050 078 002Shiny Cowbird (Molothrus bonariensis) 02plusmn 02 00 03plusmn 02 369 016 012Smooth-billed Ani (Crotophaga ani) 00 07plusmn 05 80plusmn 63 808 0018 025Thick-billed Vireo (Vireo crassirostris) 03plusmn 03 64plusmn 17 25plusmn 08 1168 0003 037Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura) 00 34plusmn 24 54plusmn 15 1020 0006 032Western Spindalis (Spindalis zena) 70plusmn 17 33plusmn 13 03plusmn 03 1122 0004 035White-crowned Pigeon (Patagioenas leucocephala) 50plusmn 25 55plusmn 44 03plusmn 02 446 011 014Zenaida Dove (Zenaida aurita) 00 11plusmn 11 00 167 044 005

NotesaNon-resident migratory speciesbIntroduced species

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 719

habitat (12km) Although Bahama Orioles were not detected in pine forest during thesesurveys they were occasionally observed in this habitat during subsequent work (Price Leeamp Hayes 2011)

The density of the Bahama Oriole can be compared to that of other species in Table 1where some structuring of bird communities is evident Thick-Billed Vireo (Vireocrassirostris) was significantly associated with coppice Black-Faced Grassquit (Tiarisbicolor) Blue-Gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea) Greater Antillean Bullfinch (Loxigillaviolacea) Pine Warbler (Setophaga pinus) and Western Spindalis (Spindalis zena) weresignificantly associated with pine forest Cuban Emerald (Chlorostilbon ricordii) EurasianCollared-Dove (Streptopelia decaocto) Gray Kingbird (Tyrannus dominensis) LaughingGull (Leucophaeus atricilla) Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) Smooth-BilledAni (Crotophaga ani) and Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura) were significantly more likelyto be found in anthropogenic habitat Bananaquit (Coereba flaveola) was significantly morelikely to be found in pine forest and anthropogenic habitat

Bahama oriole foragingOf the foraging variables listed in Table 2 only the habitat type in which individualsforaged differed significantly between SY and ASY adults (P = 0003 8= 058) WhereasSY adults (N = 15) foraged in coppice pine forest and anthropogenic habitat ASY adults(N = 12) were observed foraging only in anthropogenic habitat Those SY adults foragingin anthropogenic habitat were often paired with an ASY adult (six of seven individuals)Two additional variables showed moderately large effect sizes (Table 2) suggesting thatASY adults are more general in foraging location and in substrate use whereas SY birdsare more likely to forage near the middle of vegetation (P = 013 V = 040) from leavestwigs or bark (P = 014 V = 045) Most food was obtained through perch-gleaning(93 of 27 observations) on leaves and twigs (60 of 27 observations) in the middle ofa branch (46 of 27 observations) Both SY and ASY adults were observed air-gleaningand hang-gleaning although not all of these observations were included in statisticalanalysis due to non-independence of data points Birds were observed eating insects (89of 27 observations) and berries (11) Other food items included a Caribbean hermitcrab (Coenobita clypeata) which a SY bird unsuccessfully attempted to ingest and anendemic brown anole (Norops sagrei) which was fed to hatchlings (Price Lee amp Hayes2011) Although Bahama Orioles foraged among flowers and may have ingested nectar wecould not ascertain whether their target was the nectar or insects among the flowers

Social interactionsIntraspecific and interspecific interactions were rare with only 15 social interactionswitnessed (012h of direct Bahama Oriole observation Table 3) limiting statistical powerWhile no comparisons were statistically significant the large effect sizes suggested thatsocial interactions were more likely to occur in anthropogenic habitat for ASY birds and inother habitats (pine or coppice) for SY birds (P = 0077 V = 053 note large effect size)Older (ASY) Bahama Orioles were also more likely to lsquolsquowinrsquorsquo altercations than SY birds(P = 0077 V = 053) The avian species that Bahama Orioles interacted with (intraspecific

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 819

Table 2 Comparisons of foraging variables between second-year (SY) and after-second-year (ASY) Ba-hama Oriole (Icterus northropi) adults with chi-square and t -test results Anthropogenic habitat wasdefined as human-modified areas with buildings nearby such as residential or agricultural areas Non-anthropogenic areas included coppice (broad-leaf dry forest) and pine forest

Foraging variable SY ASY Test statistic (df) P Effect sizea

Habitat Anthropogenic N = 7 N = 12 Not anthropogenic N = 8 N = 0

χ 21 = 910 0003 8= 058

Height (X plusmn SE) 52plusmn 04 49plusmn 09 t25= 032 075 d = 019Horizontal location Inner N = 3 N = 5 Middle N = 9 N = 3 χ 2

2 = 404 013 V = 040 Outer N = 2 N = 4Substrate Air N = 1 N = 0 Berries N = 0 N = 2 Flowers N = 3 N = 5 Leaves twigs or bark N = 11 N = 5

χ 23 = 548 014 V = 045

Behavior Air-gleaning N = 1 N = 0 Hang-gleaning N = 1 N = 0 Perch-gleaning N = 13 N = 12

χ 22 = 173 042 V = 025

Food item Berries N = 1 N = 2 Insects N = 14 N = 10

χ 21 = 068 041 8= 016

NotesaEffect sizes Phi (8) Cohenrsquos d and Cramerrsquos V see lsquoMethodsrsquo

vs interspecific P = 074 V = 008) and the approximate height above ground of theinteraction (P = 067 d = 011) were similar for SY and ASY birds with small effect sizes

Intraspecific competitive interactions between BahamaOrioles were not frequent (267of 15 total interactions and only 003h of direct Bahama Oriole observation) In 2009at the Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Center (AUTEC) where the highest densityof Bahama Orioles on North Andros was observed two pairs of Bahama Orioles nestedwithin 200 m of one another One oriole from each pair engaged in an aerial chase at thepresumed territory boundary No physical contact was made although the orioles sangfrom their respective territories for approximately 30 min following the encounter On twoother occasions near the beginning of the nesting season ASY adult Bahama Oriole pairswere observed chasing SY adults sometimes tussling with them to the ground

Several interspecific interactions were observed Orioles engaged a LaSagrarsquos Flycatcher(Myiarchus sagrae) a Smooth-Billed Ani a Red-Legged Thrush (Turdus plumbeus) anda House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) pair when these birds independently flew into aBahama Oriole nest tree All were chased away except for the House Sparrow pair whichshared a nest tree with a Bahama Oriole pair Orioles chased a Shiny Cowbird (Molothrusbonariensis) away from their nest area When foraging on one occasion Bahama Orioles

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 919

Table 3 Comparisons of social interactions and their outcomes between second-year (SY) and after-second-year (ASY) Bahama Oriole (Icterus northropi) adults with Chi-square and t -test results

Variable SY ASY Test statistic (df) P Effect sizea

Habitatbc

Anthropogenic N = 1 N = 9 Coppice N = 2 N = 1 χ 2

1 = 426 0077 V = 053 Pine Forest N = 1 N = 1Outcomeb

Oriole won N = 0 N = 7 Oriole lost N = 4 N = 4

χ 21 = 477 077 8= 056

Speciesd

Bahama oriole N = 1 N = 2 Northern Mockingbird N = 1 N = 3 La Sagrarsquos flycatcher N = 0 N = 1 Red-legged thrush N = 1 N = 0 Red-tailed hawk N = 0 N = 1 Shiny cowbird N = 0 N = 1 House sparrow N = 0 N = 1 Smooth-Billed Ani N = 0 N = 1 Yellow-crowned N = 1 N = 1 Night-Heron

χ 21 = 009 074 V = 008

Height above ground (XplusmnSE) 92plusmn 23 88plusmn 09 t13= 017 067 d = 011

NotesaEffect sizes Phi (8) Cohenrsquos d and Cramerrsquos V see lsquoMethodsrsquobIntraspecific and interspecific interactions were pooled for analysescHabitat type was collapsed to lsquolsquoanthropogenicrsquorsquo and lsquolsquonot anthropogenicrsquorsquo for analysisdSpecies was collapsed to lsquolsquointraspecificrsquorsquo (oriole) and lsquolsquointerspecificrsquorsquo (non-oriole) for analysis

did not interact with nearby cowbirds Northern Mockingbirds with a nest nearby chasedaway Bahama Orioles that strayed too close

We observed several cooperative efforts to chase away potential predators On oneoccasion a Bahama Oriole and three unidentified passerines chased a Red-tailed Hawk(Buteo jamaicensis) from its perch in a Caribbean pine tree On another occasion oneASY and two SY Bahama Orioles lunged repeatedly at a Yellow-crowned Night Heron(Nyctanassa violacea) which only rarely raids nests (Watts 2011) for over an hour withoutdisplacing it On two occasions Gray Kingbirds (Tyrannus dominensis) whose territoriesoverlapped with Bahama Oriole territories chased away Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura)

DISCUSSIONPopulation densities and estimatesCoppice pine forest and anthropogenic habitats contained both habitat-specialists andhabitat-generalists (Table 1) As our surveys were conducted during the breeding seasonfor many of the resident species surveyed the habitat distributions may not represent acomplete picture of the habitats important to long-term survival of both juveniles and adultsof the resident species The Bahama Oriole appears to be somewhat of a habitat-generalistbut this becomes apparent only when considering both breeding and non-breeding periods

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 1019

The BahamaOriole associates with anthropogenic habitats during the breeding season as itprefers to nest in the tallest palms available which are now introduced coconut palms in thevicinity of human residential areas (Baltz 1996 Baltz 1997 Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) TheBahamaOriole likely also benefits from increased foraging opportunities in other cultivatedplants and ready access to adjacent coppice and pine forest foraging grounds Our surveyresults late in the breeding season however suggest that fledglings with their parents moveout of anthropogenic habitats and into coppice habitat shortly after departure from nestsWe also observed a high number of SY individuals foraging and interacting socially incoppice during the breeding season Moreover during winter surveys Currie et al (2005)detected BahamaOrioles only in coppice and agricultural areas and did not observe them inpine forest lacking a coppice understory Thus these studies illustrate the contrasting needsof these birds for anthropogenic habitat which is important during the breeding seasonand coppice which appears to be important for fledglings younger birds and perhapsbirds of all ages outside of the breeding season Unfortunately coppice is often clearedby humans for agriculture and residential development (Smith amp Vankat 1992) and hasbeen recently decimated in some areas on South Andros (Lloyd amp Slater 2010 Thurston2010) This could decrease foraging opportunities and protection for fledging chicks

Our July surveys found the highest number of avian species in coppice (34 in coppice24 in pine forest and 26 in anthropogenic habitat however note the smaller distancesurveyed in pine forest habitat than in coppice) The number of species detected in eachhabitat type was more than reported in previous studies (Currie et al 2005 Lloyd amp Slater2010) but likely underestimated the number of species present in each habitat type (95CI[35ndash52] in coppice 27ndash40 in pine 26ndash40 in anthropogenic habitat) Winter survey resultson Andros by Currie et al (2005) similarly detected the highest total number of species incoppice and shrubby field habitats (26ndash27 in coppice vs 19ndash22 species in pine-dominatedhabitats anthropogenic habitats were not included in their study) A second study (Lloydamp Slater 2010) found 22 species in coppice 28 in pine forests and 36 in human-modifiedhabitat However these surveys were performed April 24ndash30 and thus detected migratoryspecies When non-resident species were removed from the comparison the number ofspecies in each habitat type (15 in coppice 23 in pine forests 19 in human-modifiedhabitat) was less than the number detected in our study particularly in coppice

A handful of species were significantly more likely to be found in human-disturbedanthropogenic habitat These included the Cuban Emerald Eurasian Collared-DoveGray Kingbird Laughing Gull Northern Mockingbird Smooth-Billed Ani and TurkeyVulture Turkey Vultures which frequent locations of trash disposal clearly benefit fromhuman-provided food resources Other forms of resource subsidies include cultivatedfields imported plants and fresh water (Faeth et al 2005) Birds associating with human-disturbed habitatsmay also be attracted to the open spaces or edges created as land is clearedfor development (Hawrot amp Niemi 1996) The frequent occurrence of Laughing Gulls inanthropogenic habitat may be in large part because of the proximity of anthropogenic areasto coastal areas Several of these birds including Laughing Gulls and Turkey Vultures mayopportunistically act as predators on newly-fledged Bahama Oriole chicks Others such asthe Northern Mockingbird may provide competition for food items

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 1119

Some species including several endemic species were never observed in agriculturalor residential areas and may be at risk if human disturbance of coppice and pine forestincreases Among the resident species the Bahama Mockingbird (Mimus gundlachii)Bahama Yellowthroat (Geothlypis rostrata) Cuban Pewee (Contopus caribaeus) GreaterAntillean Bullfinch (Loxigilla violacea) Key West Quail-Dove (Geotrygon chrysia) LaSagrarsquos Flycatcher Mangrove Cuckoo (Coccyzus minor) and Pine Warbler (Setophagapinus) were never observed in anthropogenic habitat during this study or duringsubsequent observations

ForagingFood availability and diet composition of the Bahama Oriole may change throughout theyear One study found protein-rich invertebrates to be the most common food deliveredto hatchlings of the closely related Cuban Oriole (I melanopsis) Hispaniolan Oriole (Idominicensis) and Puerto Rican Oriole (I portoricensis) whereas orioles outside of thebreeding season more often fed on carbohydrate-rich fruit flowers and nectar (GarridoWiley amp Kirkconnell 2005) Insects generally have higher densities in pine forest andcoppice habitats whereas fruit and nectar are more abundant in recently disturbed areas(Currie et al 2005) Thus we expected breeding Bahama Orioles to forage preferentiallyin pine forest and coppice and non-breeding Bahama Orioles to forage more often inanthropogenic habitat Our breeding season observations of the oriolersquos diet compositioncorresponded with previous studies of related orioles in general composition as it includedfruit nectar arthropods and occasional small vertebrates (Garrido Wiley amp Kirkconnell2005) Foraging method was also consistent with expectations as most food was obtainedthrough perch-gleaning (93 of 27 observations) a simple and relatively inexpensivemethod in terms of energy (VanderWerf 1993) Contrary to expectations however wefound that lone SY orioles foraged only in coppice and pine forest whereas ASY adultswere observed foraging only in anthropogenic habitat The Bahama Oriolersquos proclivityfor nesting in coconut palms (Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) planted primarily in associationwith human development may influence the foraging habits of ASY adults and sufficientprotein-rich sources may be present Interestingly SY Bahama Orioles paired with an ASYadult almost always foraged in anthropogenic habitat (six of seven observations) Lone SYadults may be forced out of the most desirable habitat due to despotism (Railsback Staufferamp Harvey 2003) whereas those paired with older birds either for breeding or throughdelayed dispersal potentially benefit from association with an established territory Thusthe difference in foraging habitats between SY and ASY adult orioles may have reflectedsocial structure rather than differential food availability among habitats

Social interactionsOlder (ASY) Bahama Orioles interacted more often with other birds in anthropogenichabitat and lsquolsquowonrsquorsquo altercations more often than younger (SY) Bahama Orioles The ASYbirds in anthropogenic habitat were often nesting or feeding young and may have hadmore motivation to defend territories or offspring than SY individuals without a territoryto defend Young adults may also lack the experience to outcompete other birds who

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 1219

challenge them making it more likely for them to leave an area to avoid more seriousaltercations

Intraspecific competitive interactions between Bahama Orioles were rare probably dueto the low density of the Bahama Oriole population Competitive interactions betweenASY adults were only observed in areas where visible signs of lethal yellowing disease wereabsent from the coconut palms and Bahama Oriole density was notably higher (cf PriceLee amp Hayes 2011) Aggressive interactions between ASY and SY adults may have involvedparents chasing away offspring from a previous brood prior to beginning a new breedingseason or the SY adults may have been young males encroaching on the territories of ASYadults Long-term studies of individuals marked during their hatch year are needed toelucidate interactions within family groups and during recruitment of juveniles

Conservation implicationsDry tropical forestOur findings concur with other studies that indicate coppice is vitally important to residentmigrating and wintering birds in the Bahamas including the critically endangered BahamaOriole (Raffaele et al 2003 Lloyd amp Slater 2010) Our surveys found the highest numberof avian species during the breeding season in coppice (34 in coppice 24 in pine forestand 26 in anthropogenic habitat) Young Bahama Orioles often foraged in coppice andfledglings leaving nests in anthropogenic habitat fledged to coppice (Price Lee amp Hayes2011) As all species interact with one or more other species in food webs via competitionpredation parasitism or mutualism future studies should elucidate interactions withinthese habitats as conservation efforts are more likely to succeed when these complex foodweb interactions and the ways human activities alter them are understood (Faeth et al2005)

Caribbean pine forestCaribbean pine forests onAndros logged heavily throughout the last century have returnedas homogenous even-aged stands with closely-spaced slender trees (Currie et al 2005)This has likely decreased avian diversity compared with old-stand forests as snags cavitytrees hardwoods and large downed woody material are largely absent within secondary-growth pine forests (Thill amp Koerth 2005) Hardwood forests purposefully managed toretain or increase large live trees snags and coarse woody debris have increased densitiesof many birds of conservation concern (Twedt amp Somershoe 2009) Young Bahama Oriolesoften feed in the pine forest (this study) and adults nest in areas where a palm understoryexists (Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) as well as in suitable pine trees (Stonko et al in press)Given the importance of the wide swaths of Caribbean pine forest to migratory winteringand permanent resident species conservation plans should consider management of pineforests to increase heterogeneity and to protect the limited old growth forest that remains

Anthropogenic areasNot all avian species will decline with human disturbance and some may even benefitfrom resource subsidies and increases in open and edge habitats including those withinanthropogenic areas (Werner Hejl amp Brush 2007 Kamp et al 2009 Coulombe Kesler amp

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 1319

Gouni 2011) The Bahama Oriole uses anthropogenic areas during the breeding seasonwhere it selects nest sites in the tallest available palm trees (Price Lee amp Hayes 2011)Breeding in anthropogenic areas may result in higher levels of nest parasitism from ShinyCowbirds (Baltz 1996 Baltz 1997 Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) but the benefits of greaternest height for predator avoidance of nonnative cats rats and snakes such as the nativeBahamian Boa (Chilabothrus strigilatus) might offset any such disadvantage (cf Burhansamp Thompson 2006) Adult Bahama Orioles in particular appear to benefit from foragingin anthropogenic areas during the breeding season (this study)

The Bahama Oriole requires multiple vegetation types throughout its life history Thisis consistent with recent studies which highlight the importance of conserving habitatsimportant to all life stages rather than only those important to nesting (Streby Refsnideramp Andersen 2014) In particular the Bahama Oriole will benefit from careful managementof both coppice which is currently at high risk of rapid loss due to increasing developmenton Andros (Lloyd amp Slater 2010 Thurston 2010) and pine forest which has become morehomogenous following deforestation and frequent human-caused forest fires (Currie et al2005) Planning for future development on Andros (Inter-American Development Bank2014) should make a concerted effort to minimize disturbance of these critical habitats

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSWe thank V Lee E Gren S Myers V Myers and K Ingrey for assisting with field work

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION AND DECLARATIONS

FundingFunding was provided by the Insular Species Conservation Society and by the Departmentof Earth and Biological Sciences at Loma Linda University The funders had no role in studydesign data collection and analysis decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript

Grant DisclosuresThe following grant information was disclosed by the authorsInsular Species Conservation SocietyDepartment of Earth and Biological Sciences at Loma Linda University

Competing InterestsThe authors declare there are no competing interests

Author Contributionsbull Melissa R Price conceived and designed the experiments performed the experimentsanalyzed the data wrote the paper prepared figures andor tables reviewed drafts of thepaperbull WilliamKHayes conceived anddesigned the experiments analyzed the data contributedreagentsmaterialsanalysis tools wrote the paper prepared figures andor tablesreviewed drafts of the paper

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 1419

Animal EthicsThe following information was supplied relating to ethical approvals (ie approving bodyand any reference numbers)

Research was approved by the Loma Linda University Institutional Animal Care andUse Committee (Protocol Number 8120010)

Field Study PermissionsThe following information was supplied relating to field study approvals (ie approvingbody and any reference numbers)

Field experiments were approved by The Bahamas Environment Science andTechnologies Commission (BEST) No permit number was assigned but the signedpermit is included as supplemental file

Data AvailabilityThe following information was supplied regarding data availability

The raw data is included in the tables in the manuscript

REFERENCESAllen JA 1890 Description of a new species of Icterus from Andros Island Bahamas Auk

7343ndash346 DOI 1023074067555Ausprey IJ Rodewald AD 2011 Postfledging survivorship and habitat selection across a

rural-to-urban landscape gradient Auk 128293ndash302 DOI 101525auk201110158Baltz ME 1996 The distribution and status of the Shiny Cowbird on Andros Island

Bahamas Journal of Science 32ndash5Baltz ME 1997 Status of the Black-Cowled Oriole (Icterus dominicensis northropi) in the

Bahamas Unpublished report to the Department of Agriculture Nassau BahamasBanda K Delgado-Salinas A Dexter KG Linares-Palomino R Oliveira-Filho A Prado

D PullanM Quintana C Riina R Rodriguez GMWeintritt J Acevedo-RodriguezP Adarve J Alvarez E Aranguren AB Arteaga JC Aymard G Castano A Ceballos-Mago A Cogollo A Cuadros H Delgado F DeviaW Duenas H Fajardo LFernandez A FernandezMA Franklin J Freid EH Galetti LA Gonto R Gonzalez-M R Graveson R Helmer EH Idarraga A Lopez R Marcano-Vega H MartinezOG Maturo HMMcDonaldMMcLaren K Melo O Mijares F Mogni V MolinaD Moreno NDP Nassar JM Neves DM Oakley LJ OathamM Olvera-Luna ARPezzini FF Dominguez OJR Rios ME Rivera O Rodriguez N Rojas A Sarkinen TSanchezM Smith C Vargas B Villanueva B Pennington RT 2016 Plant diversitypatterns in neotropical dry forests and their conservation implications Science3531383ndash1387 DOI 101126scienceaaf5080

Baudouin L Lebrun P 2009 Coconut (Cocos nucifera) DNA studies support thehypothesis of an ancient Austronesian migration from Southeast Asia to AmericaGenetic Resources and Crop Evolution 56257ndash262 DOI 101007s10722-008-9362-6

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 1519

Bentz AB Siefferman L 2013 Age-dependent relationship between coloration andreproduction in a species exhibiting delayed plumage maturation in females Journalof Avian Biology 4480ndash88 DOI 101111j1600-048X201205730x

Berggren A Armstrong DP Lewis RM 2004 Delayed plumage maturation increasesoverwinter survival in North Island robins Proceedings of the Royal Society B2712123ndash2130 DOI 101098rspb20042846

Bowman R Leonard Jr DL Backus LK Mains AR 1999 Interspecific interactionswith foraging red-cockaded woodpeckers in South-Central FloridaWilson Bulletin111346ndash353

Burhans DE Thompson FR 2006 Songbird abundance and parasitism differbetween urban and rural shrublands Ecological Applications 16394ndash405DOI 10189004-0927

Carey E Gape BN Manco D Hepburn RL Smith L D Knowles Knowles M DanielsMA Vincent E Freid B JestrowMP Griffith M Calonje AWMeerowDWStevenson J Francisco-Ortega L 2014 Plant conservation challenges in the Bahamaarchipelago Botanical Review 80265ndash282 DOI 101007s12229-014-9140-4

Child R 1974 Coconuts 2nd edition London LongmansCohen J 1988 Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences 2nd edition Hillsdale

Erlbaum AssociatesCohen EB Lindell CA 2004 Survival habitat use and movements of fledgling White-

Throated Robins (Turdus assimilis) in a Costa Rican agricultural landscape Auk121404ndash414 DOI 1016420004-8038(2004)121[0404SHUAMO]20CO2

Cohen EB Lindell CA 2005Habitat use of adult White-Throated Robins during thebreeding season in a mosaic landscape in Costa Rica Journal of Field Ornithology76279ndash286 DOI 1016480273-8570-763279

Coulombe GL Kesler A Gouni DC 2011 Agricultural coconut forest as habitat forthe critically endangered Tuamotu Kingfisher (Todiramphus gambieri gertrudae)128283ndash292 DOI 101525auk201110191

Currie DWunderle Jr JM Ewert DN AndersonMR Davis DN Turner J 2005Habitatdistribution of birds wintering on Central Andros The Bahamas implications formanagement Caribbean Journal of Science 4175ndash87

Dent DHWright JS 2009 The future of tropical species in secondary forests a quantita-tive review Biological Conservation 1422833ndash2843DOI 101016jbiocon200905035

Emlen JT 1971 Population densities of birds derived from transect counts Auk88323ndash342 DOI 1023074083883

Emlen JT 1977 Land bird communities of Grand Bahama Island the structure anddynamics of an avifauna Ornithological Monographs 241ndash129

Faeth SHWarren E Shochat PS MarussichWA 2005 Trophic dynamics in urbancommunities BioScience 55399ndash407DOI 1016410006-3568(2005)055[0399TDIUC]20CO2

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 1619

Gall MD Hough LD Fernaacutendez-Juricic E 2013 Age-related characteristics of foraginghabitats and foraging behaviors in the black phoebe (Sayornis nigricans) Southwest-ern Naturalis 5841ndash49 DOI 1018940038-4909-58141

Gardner TA Barlow R Chazdon RM Ewers CA Harvey CA Peres NS Sodhi J 2009Prospects for tropical forest biodiversity in a human-modified world Ecology Letters12561ndash582 DOI 101111j1461-0248200901294x

Garrido OHWiley JW Kirkconnell A 2005 The genus Icterus in the West IndiesNeotropical Ornithology 16449ndash470

Gillespie TW Lipkin L Sullivan DR Benowitz S Pau G Keppel B 2012 The rarestand least protected forests in biodiversity hotspots Biodiversity Conservation213597ndash3611 DOI 101007s10531-012-0384-1

Graham C 2001Habitat selection and activity budgets of Keel-Billed Toucans at thelandscape level The Condor 103776ndash784DOI 1016500010-5422(2001)103[0776HSAABO]20CO2

Green SB Salkind NJ 2005Using SPSS for Windows and Macintosh analyzing andunderstanding data 4th edition Upper Saddle River Pearson Prentice Hall

Hawrot RY Niemi GJ 1996 Effects of edge type and patch shape on avian com-munities in a mixed coniferndashnorthern hardwood forest Auk 113586ndash598DOI 1023074088979

HayesWK Barry Z McKenzie RX Barry P 2004 Grand Bahamarsquos Brown-headedNuthatch a distinct and endangered species Bahamas Journal of Science 1221ndash28

Heise CD Moore FR 2003 Age-related differences in foraging efficiency molt and fatdeposition of Gray Catbirds prior to autumn migration The Condor 105496ndash504DOI 1016507183

Inter-American Development Bank 2014 BH-T1040 ecosystem-based developmentfor Andros Island Available at http idbdocsiadborgwsdocs getdocumentaspxdocnum=38930099 (accessed on 17 January 2017)

Janzen DH 1988 Tropical dry forestndashthe most endangered major tropical ecosystemIn Wilson EO Peter FM eds Biodiversity Washington National Academy Press130ndash137

Kamp J SheldonMA Koshkin PF Donald RD Biedermann R 2009 Post-Soviet steppemanagement causes pronounced synanthropy in the globally threatened SociableLapwing Vanellus gregarius Ibis 151452ndash463DOI 101111j1474-919X200900938x

Koptur S William P Olive Z 2010 Ants and plants with extrafloral nectaries infire successional habitats on Andros (Bahamas) Florida Entomologis 9389ndash99DOI 1016530240930112

Larkin CC Kwit JMWunderle EH HelmerMHH Stevens MT Roberts C Ewert DN2012 Disturbance type and plant successional communities in Bahamian dry forestsBiotropica 4410ndash18 DOI 101111j1744-7429201100771x

LauranceWF GoosemM Laurance SGW 2009 Impact of roads and linear clearings ontropical forests Trends in Ecology and Evolution 24659ndash669DOI 101016jtree200906009

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 1719

Lloyd JD Slater GL 2010 Rapid ecological assessment of the avian communityand their habitats on Andros The Bahamas Unpublished report for the NatureConservancy Nassau The Bahamas

Lyu N Lloyd H Sun Y-H 2015 Delayed plumage maturation in birds and the signif-icance of condition-dependent parental care Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology691003ndash1010 DOI 101007s00265-015-1912-2

Mac Nally R Timewell CAR 2005 Resource availability controls bird-assemblage com-position through interspecific aggression Auk 1221097ndash1111DOI 1016420004-8038(2005)122[1097RACBCT]20CO2

Miller C Niemi JM Hanowski GJ Regal RR 2007 Breeding bird communities across anupland disturbance gradient in the Western Lake Superior Region Journal of GreatLakes Research 33305ndash318DOI 1033940380-1330(2007)33[305BBCAAU]20CO2

Myers RWade C Bergh D 2004 Fire management assessment of the Caribbean pine(Pinus caribaea) forest ecosystems on Andros and Abaco Islands Bahamas Globalfire initiative 2004ndash1 The Nature Conservancy Virginia

Nakagawa S 2004 A farewell to Bonferroni the problems of low statistical power andpublication bias Behavioral Ecology 151044ndash1045 DOI 101093behecoarh107

Nakagawa S Cuthill IC 2007 Effect size confidence interval and statistical significancea practical guide for biologists Biological Reviews 82591ndash605

Nickrent DL EshbaughWHWilson TK 1988 Vascular Flora of Andros IslandBahamas Dubuque KendallHunt Publishing Co

Norris JL ChamberlainMJ Twedt DJ 2009 Effects of wildlife forestry on abundanceof breeding birds in Bottomland hardwood forests of Louisiana Journal of WildlifeManagemen 731368ndash1379 DOI 1021932008-497

Price MR Lee VA HayesWK 2011 Population status habitat dependence and repro-ductive ecology of Bahama Orioles a critically endangered synanthropic speciesJournal of Field Ornithology 82366ndash378 DOI 101111j1557-9263201100340x

Raffaele HWiley O Garrido A Keith J Raffaele J 2003 Birds of the West IndiesPrinceton Princeton University Press 182ndash183

Railsback SF Stauffer HB Harvey BC 2003What can habitat preference models tell usTests using a virtual trout population Ecology 131580ndash1594 DOI 10189002-5051

Remsen JV Robinson SK 1990 A classification scheme for foraging behavior of birds interrestrial habitats Studies in Avian Biology 13144ndash160

Shochat E Lerman JM Anderies PS Warren SH Faeth SB Nilon CH 2010 Invasioncompetition and biodiversity loss in urban ecosystems Bioscience 60199ndash208DOI 101525bio20106036

Smith IK Vankat JL 1992 Dry evergreen forest (coppice) communities of NorthAndros Island Bahamas Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119181ndash191DOI 1023072997030

Steadman DW Albury B Kakuk JI Mead JA Soto-Centeno HM Singleton NAFranklin J 2015 Vertebrate community on an ice-age Caribbean Island Proceedings

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 1819

of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112E5963ndashE5971DOI 101073pnas1516490112

Steadman DW Franklin J 2015 Changes in a West Indian bird community since thelate Pleistocene Biogeography 42426ndash438 DOI 101111jbi12418

Streby HM Refsnider JM Andersen DE 2014 Redefining reproductive successin songbirds moving beyond the nest success paradigm Auk 131718ndash726DOI 101642AUK-14-691

Stonko DC Rolle LE Smith LS Scarselletta AL Christhilf JL Rowley MG Yates SSCant-Woodside S Brace L Johnson SB Omland KE New documentation of pineforest nesting by the critically endangered Bahama Oriole (Icterus northropi) Journalof Caribbean Ornithology In Press

Thill RE Koerth NE 2005 Breeding birds of even- and uneven-aged pine forests of east-ern Texas Southeastern Naturalis 4153ndash176DOI 1016561528-7092(2005)004[0153BBOEAU]20CO2

Thurston G 2010 South Andros farm road progresses Available at httpwwwthebahamasweeklycompublishbis-news-updatesSouth_Andros_farm_road_progresse

Twedt DJ Somershoe SG 2009 Bird response to prescribed silvicultural treatmentsin bottomland hardwood forests Journal of Wildlife Managemen 731140ndash1150DOI 1021932008-441

VanderWerf EA 1993 Scales of habitat selection by foraging lsquoElepaio in undisturbed andhuman-altered forests in Hawaii The Condor 95980ndash989 DOI 1023071369433

VanderWerf EA Freed LA 2003 lsquoElepaio subadult plumages reduce aggression throughgraded status-signaling not mimicry Journal of Field Ornithology 74406ndash415DOI 1016480273-8570-744406

Vega Rivera JH Rappole JH McSheaWJ Haas CA 1998Wood Thrush postfledg-ing movements and habitat use in northern Virginia The Condor 10069ndash78DOI 1023071369898

Watts BD Yellow-crowned night-heron (Nyctanassa violacea) In Rodewald PG ed Thebirds of North America Ithaca Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Werner SM Hejl SJ Brush T 2007 Breeding ecology of the Altamira Oriole in the lowerRio Grande Valley Texas The Condor 109907ndash919DOI 1016500010-5422(2007)109[907BEOTAO]20CO2

Wunderle JM 1991 Age-specific foraging proficiency in birds In Power DM edCurrent ornithology vol 8 New York Plenum Press 273ndash324

Zar JH 1996 Biostatistical analysis 3rd edition New Jersey Prentice Hall EnglewoodCliffs

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 1919

including the critically endangered Bahama Oriole which appears to depend heavilyon this vegetation type during certain life stages

Subjects Animal Behavior Ecology ZoologyKeywords Caribbean Dry tropical forest Synanthropic species Anthropogenic habitat Pineforest Delayed plumage maturation

INTRODUCTIONConservation of endangered species often depends on effective management withinhuman-modified landscapes (Gardner et al 2009) Resource subsidies in anthropogenicareas such as cultivated plants or discarded food items influence avian distributionabundance and productivity (Faeth et al 2005) Synanthropic species which affiliate withhumans often increase in disturbed areas (Kamp et al 2009 Coulombe Kesler amp Gouni2011) whereas other species including many Nearctic-Neotropical migrants may avoidsuch areas or decline following disturbance (Miller et al 2007) particularly where muchof the canopy is removed (Norris Chamberlain amp Twedt 2009)

Some species may be negatively affected by expanding agriculture and development ifmultiple habitat types are required to sustain viable populations (Cohen amp Lindell 2005)The juxtaposition of multiple habitat types can be especially important to fledglings andyoung birds whichmay leave breeding grounds in human-altered habitat for different habi-tats nearby that provide increased foraging opportunities and higher protection frompreda-tors (Cohen amp Lindell 2004Ausprey amp Rodewald 2011Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) Juvenilesare often less efficient foragers than adult birds (Wunderle 1991 Heise amp Moore 2003Gall Hough amp Fernaacutendez-Juricic 2013) and may seek habitats with reduced competitionfrom conspecifics To effectively target conservation efforts we must therefore understandthe relative contribution of each habitat type to each life stage and by extension populationstability (Dent amp Wright 2009)

The Bahama Oriole (Icterus northropi) a critically endangered island endemic extirpatedfrom Abaco Island the Bahamas in the late 20th century and remaining today only onAndros Island the Bahamas has contended with profound habitat changes since thearrival of humankind (Steadman et al 2015 Steadman amp Franklin 2015) While loggingand human development removed native breeding and foraging habitats (Currie et al2005) and potentially impacted species sensitive to roads and clearings (Laurance Goosemamp Laurance 2009) humans provided novel opportunities for feeding and nesting in theform of introduced plant species (Nickrent Eshbaugh amp Wilson 1988) Coconut palms(Cocos nucifera) for example were imported to the region by humans about 500 years ago(Child 1974 Baudouin amp Lebrun 2009) and have become the Bahama Oriolersquos favorednesting habitat (Allen 1890 Baltz 1996 Baltz 1997) most likely due to a preference forthe tallest trees available within a nest-site (Price Lee amp Hayes 2011)

Although largely a synanthropic species associated with human-altered landscapesduring the breeding season (Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) the BahamaOriole like other species(Vega Rivera Rappole amp Haas 1998 Graham 2001) may still depend on other vegetation

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 219

types to sustain various activities throughout its life cycle and may benefit from foraging inmultiple vegetation types (Cohen amp Lindell 2005) including dry tropical forest (coppice)pine forest and human-altered (anthropogenic) areas Dry tropical forest comprises one ofthe most endangered tropical ecosystems globally due to anthropogenic disturbance(Janzen 1988 Gillespie et al 2012 Banda et al 2016) In the Bahamas dry tropicalbroadleaf forest (coppice) decreased due to the effects of forest fires on ecological successionand forest clearing in themid-1900s but has largely recovered since thenHowevermuch ofwhat remains lacks protection and the secondary forest lacks heterogeneity (Myers Wadeamp Bergh 2004Currie et al 2005) butmay still be an important contributor to avian speciesdiversity (Dent amp Wright 2009) Recently coppice loss has accelerated due to developmentincreased frequency of human-caused fires and invasion by non-native vegetation duringsuccession (Smith amp Vankat 1992 Myers Wade amp Bergh 2004 Koptur William amp Olive2010 Thurston 2010 Carey et al 2014 see also Larkin et al 2012)

Because interspecific and intraspecific interactions can be influenced by habitatdistribution and foraging strategies (Mac Nally amp Timewell 2005 Shochat et al 2010)we needed a better understanding of the avian community structure in habitats used bythe Bahama Oriole Thus we began by determining the avian species composition andrelative abundance of the Bahama Oriole among three major vegetation types on AndrosCaribbean pine forest coppice and anthropogenic areas

Next we sought to better understand the importance of these three vegetation types totwo life stages of the Bahama Oriole In Bahama Orioles both males and females in theirsecond year of life though reproductively viable (Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) display plumagecoloration similar to immature birds a trait referred to as delayed plumage maturationThis trait though common in males of many species is not a common characteristicin females (Bentz amp Siefferman 2013) and may contribute to reduced aggression fromolder birds (VanderWerf amp Freed 2003) reduced predation risk (Lyu Lloyd amp Sun 2015)and increased overwinter survival (Berggren Armstrong amp Lewis 2004) A previous studysuggested that pine forests and coppice may be particularly important for young BahamaOrioles (Price Lee amp Hayes 2011) Thus in the next phase of our study we comparedthe foraging strategies and social interactions (both intraspecific and interspecific) of twoage classes of adult Bahama Orioles second-year adults and after-second-year adults inrelation to differential habitat use

METHODSStudy areaAndros Island The Bahamas is divided by bights up to 5 km wide into three mainhuman-occupied cays (North Andros Mangrove Cay South Andros) and many smalleruninhabited cays (Fig 1) Andros Island is dominated on the eastern portion by extensiveCaribbean pine forest with coppice (dry broadleaf forest) at higher elevations and inpatches interspersed within the pine forest Mangrove associated with vast tidal wetlandsand accessible only by boat dominates the western half The pine forest was heavily

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 319

Figure 1 Andros Island is divided into three large inhabited cays (North Andros Mangrove CaySouth Andros) andmany smaller uninhabited cays by channels up to 5 km acrossMap data EsriDigital Globe GeoEye Earthstar Geographics CNESAirbus DS USDA USGS AeroGRID IGN GISUser Community

logged in the mid-1900s (Myers Wade amp Bergh 2004) and old logging roads providethe only ground access to the interior Pine trees in the secondary forest are slender andclosely spaced with an understory of poisonwood (Metopium toxiferum) and palmetto(Sabal palmetto) fern or shrub (Currie et al 2005) Human settlements and agriculturaldevelopments are spread along the eastern portion of the island

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 419

Population surveys and observational effortOther studies have assessed bird composition on Andros during the winter (Currie etal 2005) and early breeding seasons (Lloyd amp Slater 2010 Price Lee amp Hayes 2011)To evaluate population density and species composition late in the Bahama Oriolersquosbreeding season we conducted line transects between 5ndash18 July 2005 in coppice pineforest and anthropogenic areas on North Andros using methods similar to Emlen (1971)Emlen (1977) and Hayes et al (2004) During this time period we expected some BahamaOriole chicks would have fledged while others were initiating second broods We walkedindividually or with an assistant at approximately 1 kmh surveying 33 transects totaling195 km with 13 surveys in coppice (98 km) 10 surveys in pine forest (24 km) and 10surveys in anthropogenic areas (73 km) Each habitat type was variable and we sampledacross the range of variability Coppice (dry broadleaf habitat) ranged from 2 m to 10m in height Pine forest survey sites included forest with an understory of poisonwood(Metopium toxiferum) and palmetto (Sabal palmetto) fern or shrub and at least one areathat had not been previously logged (primary forest) Anthropogenic areas included landswith low-density houses stores and other buildings as well as agricultural cleared landswith nearby residential dwellings We recorded all birds identified by sight or vocalizationto compare relative and habitat-specific abundance of Bahama Orioles with other speciesResearch was approved by the Loma Linda University Institutional Animal Care andUse Committee (Protocol 8120010) and conducted under a Bahamas Ministry of theEnvironment Research Permit

Foraging behaviorWe recorded foraging and social interaction data from 17 June to 13 July 2007 and 29Marchto 30 May 2009 Total time in direct observation of Bahama Orioles was approximately122 h To quantify foraging behaviors we conducted continuous focal observations ofindividuals for up to 2 h or until the bird flew out of sight We recorded the first behaviorobserved after 10-min intervals or the first behavior after a location change gt10 mwhichever came first Because foraging birds were often only within eyesight for briefperiods of time resulting in single foraging data points for many birds we includedonly the first foraging behavior per bird per day in calculations for statistical analysesWe noted age of the bird as second-year (SY) or after-second-year (ASY) based onplumage coloration (Garrido Wiley amp Kirkconnell 2005) and recorded foraging variablesper Remsen amp Robinson (1990) including habitat foraged in location of the bird substratefed upon and food identity As one cannot distinguish Bahama Orioles males and femalesby color or behavior we did not note the sex of the individual We also noted foliage speciesin which foraging occurred and location of the bird in the vegetation both horizontally(by dividing the tree into visual thirds of inner middle outer) and vertically (using aclinometer) Substrates used during foraging were recorded as air flowers berries leavestwigs ground or bark Foraging tactics were identified as perch gleaning (picking foodfrom a nearby substrate while perched) hang gleaning (picking food from a substrate whilehanging upside down) or air-gleaning (plucking insects from the air) We recorded thetype of food eaten if it could be identified

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 519

Social interactionsDuring the aforementioned focal observations all intraspecific and interspecificinteractions were also noted per Bowman et al (1999) as an aerial chase tree chaselunge or usurp The species and sex (if they could be determined) of the birds were notedas well as the directionality of each interaction and outcome of the interaction such aswhether each bird flew away or remained

Statistical analysesWe used both parametric and non-parametric tests (Zar 1996) depending on the nature ofthe dependentmeasure and whether or not assumptions weremetWe compared the distri-bution of individual bird species among the three habitats using Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAsWe compared foraging variables and social interactions between SY and ASY adult BahamaOrioles using chi-square tests for categorical data and independent-samples t -tests forcontinuous data with habitat categories collapsed to lsquolsquoanthropogenic habitatrsquorsquo and lsquolsquonotanthropogenic habitatrsquorsquo and data from 2007 and 2009 combined due to statistical similarity

We also computed effect sizes which are largely independent of sample size (in contrastto statistical significance) and more readily compared among different data sets anddifferent studies (Nakagawa amp Cuthill 2007) For Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAs we calculatedeta-squared (η2) as χ2N minus1 (Green amp Salkind 2005) with values of sim001 sim006 andge014 loosely considered smallmedium and large respectively (Cohen 1988) For pairwisecomparisons (t -tests) we relied on Cohenrsquos d using Hedgesrsquos pooled standard deviation(Nakagawa amp Cuthill 2007) withsim01sim05 andge 08 deemed smallmoderate and largerespectively (Cohen 1988) For tests of proportions (χ2) we computed Phi (ϕ) for 2times2 andCramerrsquos V for larger contingency tables with sim01 sim03 and ge05 considered smallmoderate and large (Cohen 1988) Following Nakagawa (2004) we chose not to adjustalpha for multiple tests Although some chi-square tests did not meet assumptions ofminimal expected frequencies the effect sizes corresponded well with and supported the in-terpretations of significance All analyses were performed using SPSS 170 (2008) with alphaof 005 Values are presented as mean plusmn 1 SE Rarefaction analyses to determine the likelynumber of species per vegetation type were performed using EstimateS with 1000 runs

RESULTSPopulation densitiesThe number of avian species detected late in the reproductive season (July) was higher incoppice (34) and roughly equivalent in pine forest (24) and anthropogenic habitat (26)(Table 1) The potential number of species in each habitat at the 95 confidence intervalwas calculated as 35ndash52 in coppice 27ndash40 in pine forest and 26ndash40 in anthropogenichabitat Some species clearly associated with one or two habitats whereas otherswere generalists however transects with zero counts limited statistical power and ourability to identify possible habitat preferences for a number of species including theBahama Oriole (P = 018 η2 = 011 note moderately large effect size) ASY and SYBahama Orioles were most numerous in coppice (56km) followed by anthropogenic

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 619

Table 1 Relative density by habitat (individualskm) of birds on North Andros The Bahamas from 33 line transects during June and July of2005 with KruskalndashWallis ANOVA results (Chi-square and P values) and eta-squared (η2) effect sizes

Species Pine Coppice Anthropogenic χ22 P η2

X plusmnSE X plusmnSE X plusmnSE

American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) 00 00 09plusmn 08 394 014 012Bahama Mockingbird (Mimus gundlachii) 14plusmn 08 44plusmn 23 00 689 0032 022Bahama Oriole (Icterus northropi) 00 56plusmn 44 12plusmn 06 344 018 011Bahama Swallow (Tachycineta cyaneoviridis) 05plusmn 04 20plusmn 12 15plusmn 11 092 063 003Bahama Woodstar (Calliphlox evelynae) 00 02plusmn 02 01plusmn 01 174 042 005Bahama Yellowthroat (Geothlypis rostrata) 02plusmn 02 12plusmn 06 00 683 0033 021Bananaquit (Coereba flaveola) 24plusmn 08 11plusmn 08 29plusmn 09 424 012 013Black-and-white Warblera (Mniotilta varia) 00 02plusmn 02 00 167 044 005Black-faced Grassquit (Tiaris bicolor) 154plusmn 46 55plusmn 23 03plusmn 02 1305 0001 041Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea) 102plusmn 25 46plusmn 24 11plusmn 09 1056 0005 033Black-whiskered Vireo (Vireo altiloquus) 83plusmn 26 125plusmn 42 25plusmn 10 381 015 012Common Ground-Dove (Columbina passerine) 21plusmn 11 22plusmn 10 54plusmn 22 293 023 009Cuban Pewee (Contopus caribaeus) 06plusmn 06 02plusmn 01 00 297 023 009Cuban Emerald (Chlorostilbon ricordii) 13plusmn 11 53plusmn 26 51plusmn 14 648 0039 020Eurasian Collared-Doveb (Streptopelia decaocto) 08plusmn 06 15plusmn 09 72plusmn 37 559 006 017Gray Kingbird (Tyrannus dominensis) 24plusmn 17 55plusmn 45 50plusmn 17 600 0050 019Great Lizard-Cuckoo (Saurothera merlini) 00 02plusmn 01 03plusmn 03 153 047 005Greater Antillean Bullfinch (Loxigilla violacea) 60plusmn 30 04plusmn 04 00 820 0017 026Hairy Woodpecker (Picoides villosus) 42plusmn 20 32plusmn 16 01plusmn 01 574 006 018House Sparrowb (Passer domesticus) 00 17plusmn 17 05plusmn 05 081 067 003Key West Quail-Dove (Geotrygon chrysie) 00 08plusmn 08 00 344 018 011Killdeer (Charadrius vociferous) 00 00 11plusmn 09 394 014 012La Sagrarsquos Flycatcher (Myiarchus sagrae) 08plusmn 07 14plusmn 07 00 409 013 013Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla) 00 13plusmn 11 30plusmn 10 1017 0006 032Loggerhead Kingbird (Tyrannus caudifasciatus) 00 00 00 000 100 000Mangrove Cuckoo (Coccyzus minor) 00 11plusmn 11 00 167 044 005Northern Bobwhiteb (Colinus virginianus) 23plusmn 13 04plusmn 03 00 435 011 014Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) 09plusmn 07 22plusmn 22 73plusmn 18 1534 0001 048Pine Warbler (Setophaga pinus) 26plusmn 11 05plusmn 04 00 688 0032 022Red-legged Thrush (Turdus plumbeus) 12plusmn 06 19plusmn 08 00 576 006 018Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) 00 17plusmn 17 01plusmn 01 081 067 003Rock Pigeonb (Columba livia) 02plusmn 02 03plusmn 03 22plusmn 21 050 078 002Shiny Cowbird (Molothrus bonariensis) 02plusmn 02 00 03plusmn 02 369 016 012Smooth-billed Ani (Crotophaga ani) 00 07plusmn 05 80plusmn 63 808 0018 025Thick-billed Vireo (Vireo crassirostris) 03plusmn 03 64plusmn 17 25plusmn 08 1168 0003 037Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura) 00 34plusmn 24 54plusmn 15 1020 0006 032Western Spindalis (Spindalis zena) 70plusmn 17 33plusmn 13 03plusmn 03 1122 0004 035White-crowned Pigeon (Patagioenas leucocephala) 50plusmn 25 55plusmn 44 03plusmn 02 446 011 014Zenaida Dove (Zenaida aurita) 00 11plusmn 11 00 167 044 005

NotesaNon-resident migratory speciesbIntroduced species

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 719

habitat (12km) Although Bahama Orioles were not detected in pine forest during thesesurveys they were occasionally observed in this habitat during subsequent work (Price Leeamp Hayes 2011)

The density of the Bahama Oriole can be compared to that of other species in Table 1where some structuring of bird communities is evident Thick-Billed Vireo (Vireocrassirostris) was significantly associated with coppice Black-Faced Grassquit (Tiarisbicolor) Blue-Gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea) Greater Antillean Bullfinch (Loxigillaviolacea) Pine Warbler (Setophaga pinus) and Western Spindalis (Spindalis zena) weresignificantly associated with pine forest Cuban Emerald (Chlorostilbon ricordii) EurasianCollared-Dove (Streptopelia decaocto) Gray Kingbird (Tyrannus dominensis) LaughingGull (Leucophaeus atricilla) Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) Smooth-BilledAni (Crotophaga ani) and Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura) were significantly more likelyto be found in anthropogenic habitat Bananaquit (Coereba flaveola) was significantly morelikely to be found in pine forest and anthropogenic habitat

Bahama oriole foragingOf the foraging variables listed in Table 2 only the habitat type in which individualsforaged differed significantly between SY and ASY adults (P = 0003 8= 058) WhereasSY adults (N = 15) foraged in coppice pine forest and anthropogenic habitat ASY adults(N = 12) were observed foraging only in anthropogenic habitat Those SY adults foragingin anthropogenic habitat were often paired with an ASY adult (six of seven individuals)Two additional variables showed moderately large effect sizes (Table 2) suggesting thatASY adults are more general in foraging location and in substrate use whereas SY birdsare more likely to forage near the middle of vegetation (P = 013 V = 040) from leavestwigs or bark (P = 014 V = 045) Most food was obtained through perch-gleaning(93 of 27 observations) on leaves and twigs (60 of 27 observations) in the middle ofa branch (46 of 27 observations) Both SY and ASY adults were observed air-gleaningand hang-gleaning although not all of these observations were included in statisticalanalysis due to non-independence of data points Birds were observed eating insects (89of 27 observations) and berries (11) Other food items included a Caribbean hermitcrab (Coenobita clypeata) which a SY bird unsuccessfully attempted to ingest and anendemic brown anole (Norops sagrei) which was fed to hatchlings (Price Lee amp Hayes2011) Although Bahama Orioles foraged among flowers and may have ingested nectar wecould not ascertain whether their target was the nectar or insects among the flowers

Social interactionsIntraspecific and interspecific interactions were rare with only 15 social interactionswitnessed (012h of direct Bahama Oriole observation Table 3) limiting statistical powerWhile no comparisons were statistically significant the large effect sizes suggested thatsocial interactions were more likely to occur in anthropogenic habitat for ASY birds and inother habitats (pine or coppice) for SY birds (P = 0077 V = 053 note large effect size)Older (ASY) Bahama Orioles were also more likely to lsquolsquowinrsquorsquo altercations than SY birds(P = 0077 V = 053) The avian species that Bahama Orioles interacted with (intraspecific

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 819

Table 2 Comparisons of foraging variables between second-year (SY) and after-second-year (ASY) Ba-hama Oriole (Icterus northropi) adults with chi-square and t -test results Anthropogenic habitat wasdefined as human-modified areas with buildings nearby such as residential or agricultural areas Non-anthropogenic areas included coppice (broad-leaf dry forest) and pine forest

Foraging variable SY ASY Test statistic (df) P Effect sizea

Habitat Anthropogenic N = 7 N = 12 Not anthropogenic N = 8 N = 0

χ 21 = 910 0003 8= 058

Height (X plusmn SE) 52plusmn 04 49plusmn 09 t25= 032 075 d = 019Horizontal location Inner N = 3 N = 5 Middle N = 9 N = 3 χ 2

2 = 404 013 V = 040 Outer N = 2 N = 4Substrate Air N = 1 N = 0 Berries N = 0 N = 2 Flowers N = 3 N = 5 Leaves twigs or bark N = 11 N = 5

χ 23 = 548 014 V = 045

Behavior Air-gleaning N = 1 N = 0 Hang-gleaning N = 1 N = 0 Perch-gleaning N = 13 N = 12

χ 22 = 173 042 V = 025

Food item Berries N = 1 N = 2 Insects N = 14 N = 10

χ 21 = 068 041 8= 016

NotesaEffect sizes Phi (8) Cohenrsquos d and Cramerrsquos V see lsquoMethodsrsquo

vs interspecific P = 074 V = 008) and the approximate height above ground of theinteraction (P = 067 d = 011) were similar for SY and ASY birds with small effect sizes

Intraspecific competitive interactions between BahamaOrioles were not frequent (267of 15 total interactions and only 003h of direct Bahama Oriole observation) In 2009at the Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Center (AUTEC) where the highest densityof Bahama Orioles on North Andros was observed two pairs of Bahama Orioles nestedwithin 200 m of one another One oriole from each pair engaged in an aerial chase at thepresumed territory boundary No physical contact was made although the orioles sangfrom their respective territories for approximately 30 min following the encounter On twoother occasions near the beginning of the nesting season ASY adult Bahama Oriole pairswere observed chasing SY adults sometimes tussling with them to the ground

Several interspecific interactions were observed Orioles engaged a LaSagrarsquos Flycatcher(Myiarchus sagrae) a Smooth-Billed Ani a Red-Legged Thrush (Turdus plumbeus) anda House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) pair when these birds independently flew into aBahama Oriole nest tree All were chased away except for the House Sparrow pair whichshared a nest tree with a Bahama Oriole pair Orioles chased a Shiny Cowbird (Molothrusbonariensis) away from their nest area When foraging on one occasion Bahama Orioles

Price and Hayes (2017) PeerJ DOI 107717peerj3500 919

Table 3 Comparisons of social interactions and their outcomes between second-year (SY) and after-second-year (ASY) Bahama Oriole (Icterus northropi) adults with Chi-square and t -test results

Variable SY ASY Test statistic (df) P Effect sizea

Habitatbc

Anthropogenic N = 1 N = 9 Coppice N = 2 N = 1 χ 2

1 = 426 0077 V = 053 Pine Forest N = 1 N = 1Outcomeb

Oriole won N = 0 N = 7 Oriole lost N = 4 N = 4

χ 21 = 477 077 8= 056

Speciesd