Disneyland revisited: Singapore as a poster-child for modernity and postmodernity?

description

Transcript of Disneyland revisited: Singapore as a poster-child for modernity and postmodernity?

Swansea University, Student No. 570886

Total No. of Words (including bibliography): 5,260

Disneyland revisited: Singapore as a poster-child for

modernity and postmodernity?

Introduction

This paper is an examination of modernity and post-modernity, as applicable to the

island state of Singapore. We start with William Gibson’s acerbic, witty and

outrageous critique of Singapore’s version of modernity (Gibson, 1993). Gibson’s

attempt to poke fun at Singapore is social commentary of how and why modern

society came about, in particular, the political, the economic, the social, and the

cultural processes underpinning the rise of modernity. In Singapore, the dynamics of

modernity is represented by the tension created by a government with a centralized,

bureaucratic economic structure originally designed for a more passive, receptive

audience. The reign of technocracy and the pursuit of natural sciences in the last 30

years have produced economic success and enabled self-efficiency in the “clean

dystopia” that is the Singapore nation state. Is this state of modernity sustainable in

the future of Singapore?

Next we evaluate the economic or cultural state or condition that is known as

postmodernity, and we will focus on the later phase ascribed to Ester Dyson, the

pattern recognizer, as “being digital”: “A new kind of community, not a culture, is

coming. The difference between a culture and a community is that a culture is one-

way (you can absorb it by reading it, by watching it) but you have to invest back in a

community (Brockman, 1996).” We will proceed to examine the conditions for

postmodernity that exists in Singapore as signposts for the future direction of a

technocratic island state. How will the arrival of Vegas style casinos in Singapore in

early 2010 change Singaporeans and society as a whole? Jean Baudrillard’s essay

“Disneyworld Company” where he describes that we are “no longer alienated and

passive spectators but interactive extras” (Baudrillard, 1996) is a helpful starting

point to illuminate the potential implications of the integrated resorts, that are

integrated within community and society.

1

To conclude, this paper will offer an insight as a possible way forward to develop the

radical thinking that is missing in society, and essential to the future of Singapore –

based on the reading of Jean Baudrillard’s essay “Disneyland Company” (Baudrillard,

1996).

Why Singapore?

Dispatched to investigate whether “that clean dystopia represents our techno future”,

William Gibson1 spent a few days visiting Singapore in 1994 and wrote a travelogue

for Wired magazine (Gibson, 1993) published in Sept/Oct 1993, and the relevant

excerpt follows:

Singapore is a relentlessly G-rated experience, micromanaged by a state that

has the look and feel of a very large corporation. If IBM had ever bothered to

actually possess a physical country, that country might have had a lot in

common with Singapore. There's a certain white-shirted constraint, an

absolute humorlessness in the way Singapore Ltd. operates; conformity here is

the prime directive, and the fuzzier brands of creativity are in extremely short

supply. The physical past here has almost entirely vanished. There is no slack

in Singapore. Imagine an Asian version of Zurich operating as an offshore

capsule at the foot of Malaysia; an affluent microcosm whose citizens inhabit

something that feels like, well, Disneyland. Disneyland with the death

penalty. But Disneyland wasn't built atop an equally peculiar 19th-century

theme park - something constructed to meet both the romantic longings and

purely mercantile needs of the British Empire. Modern Singapore was - bits of

the Victorian construct, dressed in spanking-fresh paint, protrude at quaint

angles from the white-flanked glitter of the neo-Gernsbackian metropolis.

These few very deliberate fragments of historical texture serve as a reminder

of just how deliciously odd an entrepot Singapore once was - a product of

Empire kinkier even than Hong Kong.

1 Author of cyberpunk novel Neuromancer, who coined the term “cyberspace”. 2

The article provoked a minor controversy and elicited a variety of reactions, including

among others, Guardian journalist Steven Poole, digerati Peter Ludlow and

architectural philosopher Rem Koolhaas. The reactions are revealing in several

respects - the successful efficiency of modernity has unforeseen consequences; in the

micro-management and control over information by government, and in the passive

consumption of standardized and mass-produced cultural products of a distinctly

Western flavor.

Guardian journalist Steven Poole (famous for his lengthy obituary on Jean

Baudrillard) places the Singapore travelogue in the context of the dystopian near-

future landscapes of Neuromancer, where control by corporations and governments

are uncovered in its many guises, even in cyberspace (Poole, 1996). In that setting, it

is not surprising that in the horrified account in 1993 of Singapore, Gibson “despises

the seamless, structured planes of corporate big business. He hunts out the gaps in the

control structure; he is the champion of the interstitial (Poole, 1996)”. This is a fairly

predictable conclusion from Gibson, as anticipated by Wired magazine.

In writing of governance structures and political sovereignty in online communities,

Peter Ludlow expressed amusement at the deliberate attack in Gibson’s description of

Singapore as the Disneyland with a death penalty, when “the real Disneyland is in

California – whose repressive penal code includes the death penalty” (Ludlow, 2001,

p. 386 footnote 43). Ludlow brief commentary is obliquely ironic for two reasons;

firstly, the US is the biggest exporter of standardized and mass-produced cultural

products with Disneyland being the epitome of global capitalist output; and secondly,

the subsequent arrival of a Las Vegas style casino to the Singapore in early 2010

brings the wholesale assimilation of US cultural products directly into Singaporean

society and individual psyche at ground zero. Disneyland is no longer imported into

Singapore, it will be living and breathing in Singapore by early 2010.

3

Architectural guru and philosopher Rem Koolhaas (Miles et al., 2000, pp. 22-24)2 had

the strongest reaction to Gibson. His focus was on the ‘new’ overwhelming the ‘old’,

and this turns the new millennium into an exercise of soullessness (Miles et al., 2000,

p. 23). He describes the Singapore Songline as “dominated by a kind of Confucian

post-modernism”. The city’s primary architects and its central government are highly

aware of this flaw in character, alluded to by the former Minister of Information and

Arts (1991-1999), George Yeo: “It may seem odd, but we have to pursue the subject

of fun very seriously if we want to stay competitive in the 21st century (cited in Miles

et al., 2000)”. Koolhaas describes Singapore as being in a “Promethean hangover”,

an anti-climax after its monumental achievement, a ‘Barthian’ state grasping for “new

themes, new metaphors, new signs to superimpose on its luxurious substance (Miles

et al., 2000, p. 23)”. This paper takes the view that Koolhaas’s critique on Singapore,

in comparison with Gibson, lacks humor and in being obstinately serious about the

urbanization, he misses the point of social construction (see Latour below).

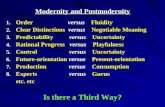

Modernity

Stuart Hall, cultural theorist of the Birmingham School, accepts the existence of

modernity, being “concerned with the process of formation which led to the

emergence of modern societies (Hall, 1996, p.3)”. Taking a historical approach to

formation of modernity, it is treated as “different processes working according to

different historical time-scales, whose interaction led to variable and contingent

outcomes (Hall, 1996, p.3)”.

Habermas similarly observed that the term has popped in and out of periods in Europe

“when the consciousness of a new epoch formed itself through a review relationship

to the ancients, whenever, moreover, antiquity was considered a model to be

recovered through some kind of imitation (Habermas and Ben-Habib, 1981, p. 6)”.

2 “Singapore Songlines: Portrait of a Potemkin Metropolis…or Thirty Years of Tabula

Rasa” from Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau “S, M, L, XL (1995)” cited in MILES, M.,

BORDEN, I. & HALL, T. (2000) The city cultures reader, London; New York,

Routledge. 4

Thus, there is no single explanation or phenomena and modernity relies on a

combination of factors in the form of social processes and structures – the political,

the economic, the social and the cultural. Modernity eludes definition due to an

amorphous nature and the evolving and non-static condition within society.

Despite the difficulty in pinpointing the condition of modernity or its very nature, we

are quite prepared to attribute the costs of modern culture – such as “civilization’s

discontents” (Freud) and increasing rationalization (Weber) – as the primary causes

for disenchantment with the modern world (Habermas and Ben-Habib, 1981, p. 6).

This presupposes we were enchanted in the first place, an interesting choice of words.

Bruno Latour, as a constructivist, explains the meaning that we ourselves have

ascribed to modernity:

‘Modern’ is thus doubly symmetrical: it designates a break in the regular

passage of time, and it designates a combat in which there are victors and

vanquished (Latour, 1993, p. 10).

Latour is critical of the use of the term “modernity” because it is used in a qualified

sense, due to our inability to maintain the double symmetry. Science and modernity

are inextricably related – the rise of science has changed the world irrevocably – we

think we are modern, and distinguished from the past. Latour argued this is too simple

a distinction for today. While Latour respects scientific method, he puts science in

context of a construction of systems that mix politics, science, technology and nature.

In fact, he argues that scientists are practical sociologists, and he argues against the

existence of post-modernity and for the illusion of modernity3.

3 “So is modernity an illusion? No, it is much more than an illusion and much less

than an essence. It is a force added to others that for a long time it had the power to

represent, to accelerate, or to summarize – a power that it no longer entirely holds.”

LATOUR, B. (1993) We have never been modern, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard

University Press., p. 405

Irrespective of whether we define modernity from a sociological view, as social

processes or discourses related to the Industrial Revolution or the Enlightenment; or

from an anthropological view, as the construction of systems that mix politics,

science, technology and nature, such that arguably there never has been modernity (or

at best, it is a moot point); it is the unshakeable belief in science and technology that

is defining modernity, and the trumping of science over social, political and

philosophical discussions.

Singapore Modernity

If modernity is defined by science, technology, industry and progress, then Singapore

should be a serious contender as a poster-child for modernity. This characterization

of a modern society is based on “the rational use of scientific techniques, and by the

application of reason to meet the common interests of all, since reason is seen as the

source of progress in knowledge and society (daCunha, 2002, p. 190)”.4 J. M. Nathan

is of the belief that the island state of Singapore has redefined modernity, as a result

of its unique geography (epicenter of Southeast Asia), its history (post-colonialism),

its multicultural and multiracial society and its dynamism (daCunha, 2002, p. 194).

This belief goes against the trend that the export of Western modernity, in particular

from the United States, has reduced the world into heterogeneous blandness of the

usual brand suspects, such as McDonalds, Hollywood movies, etc.

Singapore had to modernize, and yet, the wholesale adoption of liberal democracy,

free enterprise and rational technologies would weaken the nation-state and cultural

integrity. This has led to a paternalistic style government with a focal point “on the

solidarity of community over issues of abstract rights (daCunha, 2002, p. 194)”. In

this sense, the Singapore political leadership responsible for defining its modernity

guided not only the political economy of the nation-state but also its cultural and

spiritual well-being.

4 Article entitled – “Reframing Modernity: The Challenge of Remaking Singapore” by

J. M. Nathan Singapore in DACUNHA, D. (2002) Singapore in the new millennium :

challenges facing the city-state, Singapore, ISEAS.6

The counter-argument is that Singapore is the anti-thesis of modernity, and what has

happened is ‘modernization without modernity’ - “without the critical and self-

reflexive consciousness of modernity (Crane et al., 2002, p .164)”5. Singapore has

created a version of modernity in which the subversive and irrationality has been

subdued and its radical impulses smoothed-out (Miles et al., 2000). By contrast, Beng

Huat Chua makes the coherent argument that it may be possible to reject the Western

modernity of liberalism but not the modernity of capitalism in Singapore (Chua,

2003). Due to Singapore’s state of “embeddedness in global capitalism”, there has

been no import of Western culture imposed on Singapore, nor has there been an

existing ‘traditional’ Singapore culture. His argument is “the cultural modernity of

capitalism should be emphasized, rather than narrowly conceptualizing this modernity

as ‘Western’ (Chua, 2003, p .19).”

This paper takes the view that Singapore is a poster-child for modernity set against

global capitalism and a political economy of scientific rationality, technology,

industry and progress. Singapore is a marvel of modernization due to the very nature

of being rational, orderly, clean and obsessively compulsive. This is a post-modern

vision of a society infused with global capitalism, communitarianism (so-called Asian

values), multiculturalism (or a pluralistic society), and technology. Singapore can

therefore be a point of reference for post-modernism:

Almost all of Singapore is less than 30 years old; the city represents the

ideological production of the past three decades in its pure form,

uncontaminated by surviving contextual remnants. It is managed by a regime

that has excluded accident and randomness. Even its nature is entirely remade.

It is pure intention: If there is chaos, it is authored chaos; if it is ugly, it is

designed ugliness; if it is absurd, it is willed absurdity (Gardels, 1997, p. 171).

5 Article entitled “Cultural Policy and the City-State” (2002) by Kian-Woon Kwok

and Kee-Hong Low, which appears in CRANE, D., KAWASHIMA, N. &

KAWASAKI, K. (2002) Global culture : media, arts, policy, and globalization, New

York, Routledge.

7

Singapore is a model that therefore complies with the social and cultural view of

modernity’s achievements being limited to the free citizen and free labor but not the

free consumer, because “the values of economy and equality were calibrated to the

understanding of politics and economics (Poster, 2006, p.236)”. In Singapore case,

issues of gender relations, sexual preference, consumer patterns and emotional

dynamics were subordinate to nation building and institutional realization of political

and economic freedoms.

Post-modernity

How do you identify postmodernity? In modernity, the consumer’s role was

marginalized and played a secondary role: “Consumption was considered necessary

for the reproduction of labor and the satisfaction of needs (Poster, 2006, p. 236)”.

The complexity and importance of consumption is a salient feature of postmodernity.

This is supported by Michel de Certeau who criticized social scientists for using

quantitative methods to study consumption - blinded by science, and failed to see that

consumption has its own trajectory – because consumption ‘moves’ and can be

indiscriminate (Poster, 2006, p. 238). The difference is the way an individual

identifies with the object that is consumed. In modernity, the consumer maintains the

object of consumption as separate or apart from him/her. In postmodernity, “the

consumer renders products of her/himself, becoming part of the experience being with

products (Poster, 2006, p. 242)” The consumer in modernity equates consumption

with status, while in postmodernity, it is identity.

Postmodernity is associated with new media because of “speed, flexibility, digitality,

hypertextuality (Lister, 2003, p. 192)” as their defining characteristics. Therefore, the

consumption of digital media is a key characteristic of postmodernity – this is because

the consumer transforms the objects by virtue of their consumption. The individual

become more than a mere consumer, and turns into a creator of new digital media

content. The change in consumption, digitality and the consumer evolution into a

“prosumer” (Benkler, 2006) are significant factors in “being digital” and the process

of decentralization into the building of communities. Esther Dyson, the pattern

recognizer, spotted this development before many others:

8

It's not between democracy and tyranny. It's decentralization. More and more

things are chosen individually. It's the primacy of the small unit. You can now

be as efficient in a small unit as you are in a big unit (Brockman, 1996).

In addition to the difference in consumer consumption, and the association of new

media in the change from modernity to postmodernity, the third way to identify

postmodernity is the collapse of modern culture (Jean Baudrillard) or any changes in

the culture of capitalism (Fredric James). For Baudrillard, the postmodern world is

hyperreal - in a postmodern world, “we are involved in the empty and meaningless

play of the media (Lane, 2009)”. This means we are playing a part and the symbolic

meaning is destroyed specifically our past, and instead a chaotic and empty world

replaces it. The pervasiveness of electronic communication and mass media “has

reversed the Marxist theorum that economic forces shape society. Instead, social life

is influenced above all by signs and images (Giddens and Griffiths, 2006)”. Meaning

in our lives is replaced by images, through TV, so that we are walking around in a

make-believe universe where we are responding to media images instead of

interacting with real people. It is difficult to separate our real lives from the reality

created by media images, TV, etc (Giddens and Griffiths, 2006).

Baudrillard refers to Disneyland as a metaphor of hyperreality – the Disneyland

themes parks are fictional worlds where the use of technology, and the simulation of a

false reality, is so desirable and attractive, consumers come back for more each time.

The simulated reality has, in actual fact, become more real, i.e. hyper-real. This is

acutely described in Simulacra and Simulations:

The Disneyland imaginary is neither true or false: it is a deterrence machine

set up in order to rejuvenate in reverse the fiction of the real. Whence the

debility, the infantile degeneration of this imaginary. It’s meant to be an

infantile world, in order to make us believe that the adults are elsewhere, in the

‘real’ world, and to conceal the fact that real childishness is everywhere,

particularly among those adults who go there to act the child in order to foster

illusion of their real childishness. (Baudrillard and Poster, 1999, pp. 166-184)

9

Baudrillard is still influential and popular, and widely associated with postmodernism,

because his work “has been animated by the dual project of tracing the new forms of

social control that govern and produce us and searching for and discovering forces

which opposed and reversed this perfected system (Merrin, 2005, p. 99)”.

Singapore Postmodernity

Any visitor who asks, “what can I do in Singapore” receives the standard response:

there are only three things to do – shopping, eating and watching movies. And the

proof is in the pudding because Singapore has become a consumer heaven with

overwhelming evidence of a consumer culture comparable to those of advanced

developed nations. It is not hype to state that Singapore’s consumer lifestyle is better

than most of the world’s major cities. All the major fast food chains, major fashion

labels, luxury cars, shopping malls selling only electronic items, even specializing in

high-technology products. This consumer phenomenon has prompted the Prime

Minister of Singapore in his 1996 National Day Rally Speech (akin to the UK Prime

Minister’s speech or the US State of the Union address) to proclaim – “Life for

Singaporeans is not complete without shopping!” (Chua, 2003)6

The recognition given by the Singapore leadership to significant developments in the

cultural industry, was swiftly followed up by pragmatic economic development and

investment in theatre, popular media and the arts over the last decade. Andrey Yue

makes an astute observation that “Underpinning this growth is the emergence not only

of culture, but of an expedient culture that has the capacity to transform everything

into a practical resource (Yue, 2006, p. 3)”. In this state of ultra-consumerism in

Singapore, there emerges three distinct characteristics which point to the emergence

of a capitalist postmodern consumer culture: firstly, the speed and volume of

consumption due to unprecedented economic progress such that consumerism is a

culture among Singaporeans, secondly, consumption patterns are demarcated by class,

age, gender, sexuality, race and nationality, and thirdly, these patterns provide fertile

ground for new practices described by Michel de Certeau as ‘acts of doing’ to

reconstitute identity and potentially disrupt hegemony (Yue, 2006, p.3).

6 The proclamation was reported in The Straits Times, 18 August 1996.10

Yue cites the example of gay and lesbian consumption in Singapore to support her

argument of the existing and continuous development of identity subcultures in

Singapore despite government intervention: “The acquisition of citizenship as

consumership is evident in how gay and lesbian consumption in the last five years has

outstripped Sydney as the queer capital in the Asia-Pacific region. Despite the

illegality of homosexuality and the censorship of gay Internet content by the

Singapore Broadcasting Authority, a queer culture has emerged through AIDS

organizations, gay and lesbian activism and especially queer life-style consumption

(Yue, 2006, p.8)”.

The government clearly recognizes these trends described by Yue and their potential

not for disruption, but for continuing and maintain economic progress. The Singapore

government is promising yet another remarkable transformation and this involves an

experiment on media, society and culture on a massive scale. Terence Lee has

examined the latest Singapore initiative of a cultural revolution set out in the report

from the Creative Industries Working Group (CIWG) of the Economic Review

Committee (ERC), a government appointed, high-level body tasked to identify future

economic growth sectors and opportunities in Singapore(Lee, 2007). The Media 21

initiative “…envisions Singapore as ‘a global media city, a thriving media ecosystem

with roots in Singapore, and with strong extensions internationally (Lee, 2007, p. 8)”.

There are strong elements of McLuhan’s Extensions of Man in this statement. The

vision of a Renaissance City 2.0 was to “…(re)package the city-state as a creative and

vibrant place to ‘live, work and play’ – a contemporary catchphrase in Singapore – for

both local and foreign talents (Lee, 2007, p. 2)”. The Renaissance City is an allusion

to the Age of Enlightenment. At first blush, Singapore government is reinforcing

modernity by harking back to Enlightenment and McLuhanism. Its rhetoric however

conveys post-modernity – embracing counter-enlightenment ideas and post-liberalist

concepts of culture, society and identity. Lee criticizes the Singapore government for

the use of marketing and PR for “sexing up Singapore (Lee, 2007, p. 14)”. He remains

skeptical and argues that the efforts to liberalize Singapore are cosmetic and ‘gestural’

(Lee, 2007, p.11).

11

These transformations included the over-turning of a long-standing ban on casinos,

and investments from Las Vegas Sands (Yahoo!, 2006)7 and Genting Group (Genting,

2006)8 to construct two gaming-entertainment venues – known as integrated resorts –

in Singapore. William Gibson’s slanted critique of the Singapore Disneyland, in the

current context of the arrival of gaming-entertainment venues in Singapore as part of

the remaking of its post-modern future, may not be pure coincidence. His past track

record of recognizing the trend, and naming it (i.e. cyberspace), it is prescient of

Gibson to attribute the remaking of Singapore with “Disneyland”. What we would

call the new “Disneylandscape” of Singapore.

In reading Jean Baudrillard’s essay Disneyworld Company (Baudrillard, 1996), one

cannot help but wonder about the corporate values and cultural signifiers that come

with the packaged deal of the casino operators. Other multi-national corporations

operate in Singapore, so what is the big deal one might ask? The difference is subtle

and yet significant – the casino operators are bringing the entertainment Las Vegas

style to Singapore’s doorstep, in their backyard and to friends, relatives and

acquaintances. Hyperreality, as described by Jean Baudrillard, is complete:

But we are not longer in a society of spectacle, which itself has become a

spectacular concept. It is no longer the contagion of spectacle that alters

reality, but rather the contagion of virtuality that erases the spectacle.

Disneyland still belonged to the order of the spectacle and of folklore, with its

effects of entertainment [distraction] and distanciation [distance]. Disney

World and its tentacular extension is a generalized metastasis, a cloning of the

world and of our mental universe, not in the imaginary but in a viral and

virtual mode. We are no longer alienated and passive spectators but

interactive extras (figurants interactifs); we are meek lyophilized members of

this huge ‘reality show’ (Baudrillard, 1996)”.

Each Singaporean is no longer a passive spectator, and will become ‘interactive

extras’ in Disneyland. Each Singaporean is transformed into a performer in a vast and 7 Article can be found at: http://sg.biz.yahoo.com/060526/1/4153y.html 8 Article can be found at:

http://www.genting.com/press/2006/GentingIntlandStarCruisesPressRelease_08Dec2006.pdf 12

macabre reality show facilitated by media, culture, society and technology. Singapore

will be at once entertained and at the same time, distant and become indifferent to the

surroundings. Singapore Inc is transformed into “Singapore Spectacular, Inc”:

In 1911, George Simmel in his extraordinary essay “The Metropolis and Mental Life”

considered the implications of modern urban life for the individual - how would we

respond, internalize, assimilate and digest the myriad of diverse experiences and

stimuli resulting from modernity? The cost of modernity is “treating others in

objective and instrumental terms (Harvey, 1990, p. 26)”.

Furthermore, we would “surrender ourselves to the hegemony of calculating

economic rationality” and we would build up a “blasé attitude” from filtering out the

complex stimuli to tolerate the extremes. George would argue it is a “sham

individualism through pursuit of signs of status, fashion, or marks of individual

eccentricity” and he is right on the money. In fact, Singaporeans revel in sham

individualism and exceed all expectations in this area.

Finally, what will post-modernity in a Disneylandscape bring? This question will

require further analysis and research. It is a beginning of a serious of questions to

elicit answers, in the context of a construction of systems that mix politics, science,

technology and nature, in the hyperreality of Disneylandscape.

Conclusion

To conclude, Gibson’s penchant for spotting a new paradigm, and naming it first

(“cyberspace”) has to be taken seriously. The anointment of Singapore with the tag

of “Disneyland” and the arrival of Disneylandscape in the form of integrated resorts,

the Media 21 and Renaissance City 2.0 initiatives are not mere coincidences.

This paper predicts that Rems Koolhaas got it wrong when he described Singapore as

suffering from a Promethean hangover. The Singapore social experiment to blend

media, society and culture on a massive scale, in a grand promise as a Renaissance

13

City 2.0, is happening and only execution and the finished product remains to be seen.

There is no denying the forces behind “Singapore Spectacular, Inc.”

Singapore has an unshakeable belief in science and technology. The investments it

has made over the last 30 years, and continue to make, in the development of natural

sciences is a defining characteristic of modernity. The rational use of scientific

techniques and the application of reason in the name of progress in knowledge and

society, has consequently triumphed over social, political and philosophical themes.

Set against the backdrop of global capitalism and a political economy of scientific

rationality, technology, industry and economic progress, Singapore personifies

“modernity” with its ruthless and vicious subordination of gender relations, sexual

preference, consumer patterns and emotion dynamics to realize political and

economic freedoms.

In the past decade, there are a few significant changes, which have had an impact on

how Singapore perceives itself in the world stage, and its role in postmodernity. The

complexity and importance of consumption patterns was the first significant factor in

postmodernity. Blinded by science and its quantitative methods, the consumer was

seen as a passive receptor. In postmodernity, the consumer is identifies with the

object that is being consumed, and becomes part of the experience with the product,

creating its own identity. The second significant factor is the association of new

media with postmodernity, bringing about the speed, flexibility, digitality and

hypertextuality to change the nature of consumption. The consumer is a creator and

producer of new digital media content. The third significant factor, and the missing

radical link, is the demise of modern culture into hyperreality. In a post-modern life

where we are playing a part and the symbolic meaning is destroyed, including our

past, to be replaced by a chaotic and empty world. This is the Disneyland effect.

Singapore, in the throes of post-modernity, has recognized the oncoming sea of

change produced by the amalgamation of media, society/culture and technology. The

ultra-consumerism society of Singapore is reflected by the mantra “Life for

Singaporeans is not complete without shopping!” Another remarkable transformation

14

is promised to Singaporeans in the Media 21 and Renaissance City 2.0 initiatives.

Ironically, these initiatives are strong reminders of McLuhanism and the Age of

Enlightenment, which is beset in modernity. The rhetoric of Singapore’s politicians

however convey post-modernity – embracing counter-enlightenment ideas and post-

liberalist concepts of culture, society and identity – as seen from marketing and PR

for “sexing up Singapore”.

The missing radical link is the demise of the modern culture, as exemplified by

Gibson’s critique using the Disneyland effect. In this paper’s analysis, using Jean

Baudrillard’s description of hyperreality, the arrival of Disneylandscape in the

integrated resorts to Singapore, spells the transformation over time of every

Singaporean into an “interactive extra” in Disneyland. Singaporeans will evolve into

performers of a vast and macabre reality show through the skewing lens effect of

entertainment and distanciation. In this hyperreality, Singaporeans would further

surrender to the hegemony of calculating economic rationality and the sham

individualistic pursuit of signs of status, fashion or personal identity. Singapore, Inc,

will be transformed into Singapore Spectacular, Inc – the virtual reality show.

BAUDRILLARD, J. (1996) Disneyword Company. The European Graduate School website. The European Graduate School.

BAUDRILLARD, J. & POSTER, M. (1999) Simulacra and simulations. Alexandria, VA, USA; Cambridge, UK, Chadwydk-Healey.

BENKLER, Y. (2006) The wealth of networks: how social production transforms markets and freedom, New Haven CT, Yale University Press.

BROCKMAN, J. (1996) The Pattern Recognizer: Esther Dyson. IN BROCKMAN, J. (Ed.) Digerati: Encounters with the Cyber Elite. HardWired Books.

CHUA, B. H. (2003) Life is not complete without shopping : consumption culture in Singapore, Singapore, Singapore Univ. Press, National Univ. of Singapore.

CRANE, D., KAWASHIMA, N. & KAWASAKI, K. (2002) Global culture : media, arts, policy, and globalization, New York, Routledge.

DACUNHA, D. (2002) Singapore in the new millennium : challenges facing the city-state, Singapore, ISEAS.

GARDELS, N. (1997) The changing global order : world leaders reflect, Malden, Mass., Blackwell Publishers.

GENTING (2006) Resorts World at Sentosa to welcome visitors to Singapore by 2010. Singapore, Genting Group.

GIBSON, W. (1993) Disneyland with the Death Penalty. Wired Magazine Online. Conde Nast Publications.

15

GIDDENS, A. & GRIFFITHS, S. (2006) Sociology, Cambridge, UK [u.a.], Polity Press.

HABERMAS, J. & BEN-HABIB, S. (1981) Modernity versus Postmodernity. New German Critique, 3-14.

HALL, S. (1996) Modernity : an introduction to modern societies, Cambridge, Mass., Blackwell.

HARVEY, D. (1990) The condition of postmodernity : an enquiry into the origins of cultural change, Oxford, Blackwell.

LANE, R. J. (2009) Jean Baudrillard, London, Routledge.LATOUR, B. (1993) We have never been modern, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard

University Press.LEE, T. (2007) Towards a 'New Equilibrium': The Economics and Politics of the

Creative Industries in Singapore.LISTER, M. (2003) New media : a critical introduction, London; New York,

Routledge.LUDLOW, P. (2001) Crypto anarchy, cyberstates, and pirate utopias, Cambridge,

Mass., MIT Press.MERRIN, W. (2005) Baudrillard and the media : a critical introduction, Cambridge

[u.a.], Polity.MILES, M., BORDEN, I. & HALL, T. (2000) The city cultures reader, London; New

York, Routledge.POOLE, S. (1996) Virtually in Love. The Guardian Online. London, The Guardian

Newspaper.POSTER, M. (2006) Information please : culture and politics in the age of digital

machines. Durham [u.a., Duke Univ. Press.YAHOO! (2006) Las Vegas Sands wins Singapore's first casino license. Yahoo

Singapore Finance. Singapore, Yahoo! Pte Ltd.YUE, A. (2006) The Regional Culture of New Asia - Cultural governance and

creative industries in Singapore. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 12.

16