Delaware Theatre Company's Ain't Misbehavin' Study Guide

-

Upload

delaware-theatre-company -

Category

Documents

-

view

229 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Delaware Theatre Company's Ain't Misbehavin' Study Guide

INSIGHTS DTC’s Teacher Resource

Ain’t Misbehavin’

Music by Thomas “Fats” Waller Conceived by Murray Horwitz and Richard Maltby, Jr.

April 2—27, 2014 Delaware Theatre Company

INSIGHTS Published March 2014

Delaware Theatre Company

200 Water Street

Wilmington, DE 19801

(302) 594-1100

www.delawaretheatre.org

35th Season —2013-14

***

AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’

Music by Thomas “Fats” Waller

Conceived by Murray Horwitz and

Richard Maltby, Jr.

Directed by

Richard Maltby, Jr.

*** Delaware Theatre Company

Executive Director

Bud Martin

Director of Education and

Community Engagement

Charles Conway

Associate Director of Education and

Community Engagement

Johanna Schloss

Ed. & Community Engagement Assoc.

Allie Steele

Contributing Writers

Johanna Schloss

1

Thoughts on Jazz . . .

The real power of jazz, and the innovation of jazz, is that a group of people can come together and create art, improvised art, and can negotiate their agendas with each other, and that negotiation is the art. —Wynton Marsalis It is America’s music, born out of a million American negotia-tions, between having and not having, between happy and sad, country and city, between black and white, and men and women…. It is about just making a living, and taking terrible risks, losing everything, and finding love, making things simple, and dressing to the nines. —Geoffrey Ward

Jazz music celebrates life, human life, the range of it, the absurdity of it, the ignorance of it, the greatness of it, the intelligence of it, the sexuality of it, the profundity of it, and it deals with it. —Wynton Marsalis Quotations taken from the introduction to Ken Burns’ miniseries Jazz.

Delaware Theatre Company thanks the following sponsors for supporting its educational and artistic work.

This program is made possible, in part, by a grant from the Delaware Division of the Arts, a state agency dedicated to nur-turing and supporting the arts in Delaware, in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts.

The Characters

2

There are five actors/singers in the show, as well as six members of an onstage band. The ensemble together creates the feel of a jazz club in Harlem during the time of the Harlem Renaissance (the 1920s and early 1930s). The actors and musicians are playing characters from that time and place (though they may use their real names in conversation).

Summary Unlike many other musicals, Ain’t Misbehavin’ does not follow a traditional plot arc as the piece unfolds. More in the style of a musical revue, the show features a cavalcade of songs one after another. At times pairs or groups of songs are linked to one an-other thematically; other times, songs may be sung back-to-back as though they are telling characters’ stories or illuminating their relationships to one another. Still other times, songs are con-nected simply by their style—perhaps a set of jumpy dance tunes performed in sequence, or a series of torch songs in a slow, soul-ful style. Between the songs, the characters interact, allowing the audience to see qualities of their personalities and relationships, such as who has a sense of mischief or who is romantically inter-ested in whom. Though not every song in Ain’t Misbehavin’ was written by Thomas “Fats” Waller, each piece is linked to him be-cause he composed, performed, and/or made the song famous in some way. Below are titles of some of the more famous tunes from the show:

“Ain’t Misbehavin’” “Honeysuckle Rose”

“’T Ain’t Nobody’s Biz-ness If I Do”

“The Joint is Jumpin’” “Your Feet’s Too Big”

“Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now”

Drawing in Two Colors

by Winold Reiss

Doug Eskew and Debra Walton are two of the performers in

DTC’s production of Ain’t Misbehavin’.

Production History

About Fats Waller

Ain’t Misbehavin’, based on an idea by Murray Horwitz and Richard Maltby, Jr., was conceived and originally directed by Maltby in 1978 at The Manhattan Theatre Club. Shortly thereafter, the show transferred to Broadway, where it ran for over 1600 performances. The show garnered two Tony Awards: one, for Best Musical, and two, for Best Direction of a Musical. The original five cast mem-bers—Ken Page, Nell Carter, Andre DeShields, Armelia McQueen, and Charlaine Woodard-- re-united for the 1988 Broadway revival. Ain’t Misbehavin’ was last seen at Delaware Theatre Company in the 1989-90 season. Our 2013-14 production is directed by Tony Award Winner Richard Maltby, Jr., creator and original director of the show.

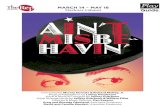

Thomas Wright “Fats” Waller (1904-1943) was born and raised in Harlem. He began playing piano at age six, started accompanying at the church where his father preached, and as a teenager began his professional career when he became the organist at Harlem’s Lincoln Theatre, where he accom-panied silent movies. He studied piano with the stride piano great James P. Johnson, and later began playing jazz music at rent parties and nightclubs in and around Harlem. In 1922, he began recording when he accompanied blues greats such as Alberta Hunter and Maud Mills. By the mid-1920s, Fats—a nickname he picked up as a child—was already a successful composer, and in 1928 he col-laborated with Andy Razaf and others on the all-black Broadway show Keep Shufflin’. He continued to find greater and greater popularity and financial success through his composing, broadcasting, recording, and accompanying work, and in the 1930s worked in Hollywood and appeared in two feature films, Hooray for Love and King of Burlesque. Waller continued touring and recording, and in 1943 starred with Lena Horne and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson in the movie Stormy Weather. He be-came ill later that year and passed away of pneumonia while journeying from Los Angeles to New York. Over 4000 people attended his funeral in Harlem.

Left, Thomas

“Fats” Waller at

the keyboard.

Right, photo of

Stormy Weather

poster featuring

Waller and other

entertainment

greats.

3

Teachable Themes and Topics

The Harlem Renaissance Harlem is a neighborhood on the New York island of Manhattan. Located just north of Central Park, with boundaries on the east of the Harlem River and on the west at the Hudson River, and on the north at 155th Street, Harlem has had a long and rich history, including a starring role during the peak years of the Jazz Age. These years—beginning after World War I and continuing until the mid-1930s—comprised a brief but shining era known as the Harlem Renaissance. The word “renaissance,” meaning “rebirth,” signifies a time of great advances and achievements for a community, particularly in terms of education and the arts. And like the Italian Renaissance of the 1500s and the English Renaissance of the late 1500-early 1600s, the Harlem Renaissance saw a cul-tural explosion as writers, musicians, visual artists, and intellectuals gathered in the same area; cre-ating, performing, and publishing with a zeal; and celebrating and influencing one another’s work. Harlem of the 1920s was the home of poets and writers such as Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Zora Neale Hurston. Harlem boasted popular speakeasies, jazz clubs, and great performance halls such as the Savoy Ballroom, the Apollo Theatre, and the Cotton Club, where musicians like Thomas “Fats” Waller, James P. Johnson, Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington delighted audiences. At the turn of the 20th century, and continuing through and beyond World War I, the “Great Migra-tion” of African-Americans from the South occurred as they sought relief from the oppression of Jim Crow laws along with the opportunities of jobs and greater freedoms in cities in the north. At the same time, political intellect and social activist W. E. B. DuBois, the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University, began editing a periodical entitled The Crisis, a publication that not only urged men and women of color to strive for education and equal rights, but also published literary works and artistic images generated by African-Americans during the Harlem Renaissance. With this vehicle for sharing information and artistic achievement, DuBois—along with the leader-ship of the NAACP, of which he was one of the cofounders—became a proponent for African-Americans shaping and sharing their own voices for a contemporary society. Racial relations in Harlem during the Jazz Age were delving into new territory. Racial segregation existed in places like the Cotton Club; which, though it allowed only white patrons, hired and pro-moted the talents of black artists like Duke Ellington. The Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, known as “The Home of Happy Feet,” was one of the major clubs that was racially integrated, allowing all people to come together and dance to the beat of jazz. In the stretch known as “Jungle Alley,” races mingled freely at clubs and speakeasies, enjoying music and dance together. In some of these venues, musicians themselves were allowed —and even sought opportunities—to cross racial barri-ers and work together playing and singing jazz music. As the Great Depression took its toll on urban areas and the job market fell apart, the economic support structure within Harlem, too, began to collapse in the mid-1930s. Famous jazz artists who once played the popular clubs were able to tour the country and even broaden their appeal through the burgeoning film industry in Hollywood, leaving behind the once-bright nightlife that filled the streets of Harlem with the sounds of stride piano and vocal scatting. Harlem fell into disrepair, and for many years was considered a blighted neighborhood of Manhattan. More recently, however, Harlem has begun enjoying a second renaissance, as new restaurants, shops, and clubs have sprung up alongside neighborhood bars and diners. An eclectic mix of cultures, Harlem today hearkens back to the brightness of the 1920s, bringing not only local patrons together in the community, but also attracting people from midtown, downtown, and beyond.

4

Teachable Themes and Topics (continued)

5

Sights and Sounds of the Harlem Renaissance

Images clockwise, from top

left: writer Zora Neale

Hurston; Harlem’s Apollo

Theatre; marker commemo-

rating the location of the

Savoy Theatre; poet

Langston Hughes; map of

Harlem

“Juke Box Love Song” by Langston Hughes

I could take the Harlem night and wrap around you, Take the neon lights and make a crown, Take the Lenox Avenue busses, Taxis, subways, And for your love song tone their rumble down. Take Harlem's heartbeat, Make a drumbeat, Put it on a record, let it whirl, And while we listen to it play, Dance with you till day-- Dance with you, my sweet brown Harlem girl.

Teachable Themes & Topics (continued)

6

Jazz: Individual Expression, Collaborative Approach “[Jazz] is America’s music. . . . It is an improvisational art, making itself up as it goes along, just like the country that gave it birth. It rewards individual expression, but demands selfless collaboration. . . .It has a rich tradition and its own rules, but it is brand new every night.” Writer Geoffrey Ward, taken from the narration of Ken Burns’ series Jazz. No study of music and music history is complete without an examination of jazz, that particular art form born of musical traditions hundreds of years old that itself gave birth to the world of rock and roll, hip hop, rhythm and blues, funk, and most other contemporary musical forms. Ask someone to describe jazz, and you may get a variety of answers—some describing the voices of particular singers or instruments, some mentioning syncopated rhythms, and others detailing moods evoked by its dis-tinctive sound. For the variety of styles encompassed by the form “jazz,” each of these descriptions is apt and can shed light on what makes a particular piece of music fit into that category. Yet one very important aspect of jazz music is the way it encourages individuality in expression in tandem with teamwork in performance. Jazz is a type of music originating in America in the late 1800s and early 1900s. As such, jazz is a veri-table gumbo of musical traditions from around the world, blended and morphed into a new style. African percussive rhythms contributed the syncopated beat; European classical works gave a melodic and harmonic line; and structures borrowed from Midwestern ragtime, Baptist hymns, and Southern blues crafted the form of jazz music. Even phrases from the Natchez and Choctaw Indian tribes, local to New Orleans and its surroundings, found their way into jazz music. Jazz became not only a form of expression for trained musicians, but also a voice for the common man. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, more and more people migrated within the United States, with a large influx of people from Southern and rural zones of the country moving into large cities, following the job market that opened up with the industrial revolution and again with the arrival of World War I. This migration brought to cities like New York, Chicago, Detroit, Kansas City, and St. Louis a musical multicultural-ism that fed the world of jazz. And the burgeoning entertainment media—as in sheet music, audio recordings, radio broadcasts, and feature films—spread this language of jazz into communities large and small across the entire country. Fats Waller was an integral part of the era that became known as the Jazz Age, a time when jazz mu-sicians enjoyed a popularity that crossed racial and economic lines and spurred further interest in this American music form. Waller, a trained pianist and organist (one resource suggests he even trained at the acclaimed Juilliard School), brought his leaping left hand—a hallmark of the stride-piano style—and creative melodies to his compositions and arrangements. At times Waller was the “star” of his performances and recordings. Other times, he played a supporting role for another featured musi-cian. Working with other talented artists such as Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, Lena Horne, Jack Teagarden, Andy Razaf, and Bessie Smith, Waller shared his talents with and accompanied the talents of these men and women, highlighting that duality of individuality in expression and collaborative spirit in performance that infuses jazz. Jazz is participatory, joining musicians of varying strengths and backgrounds and demanding interplay between them. The variety of backgrounds, skills, and experiences might seem to be an impediment to an ensemble’s being able to play together with little to no rehearsal. However, jazz musicians (continued)

Teachable Themes & Topics (continued)

Jazz: Individual Expression, Collaborative Approach (continued)

frequently use a common structure—perhaps in chords in a I-IV-V pattern (such as in the song “That Ain’t Right”), or patterns such as a walk-up or walk-down in the bass line (as in the final bars of “Ladies Who Sing with the Band”)--and then employ improvisation within that structure, taking turns as musicians in being the featured line and in accompanying the featured instrument or vocalist. Along with being skilled at singing or playing their individual instruments, jazz artists must also excel at working in a collaborative environment, listening to one another’s lines and rhythms, communicat-ing and following one another’s direction, and sharing the lead. Throughout Ain’t Misbehavin’, the on-stage band does exactly this; playing jazz standards as an ensemble, yet conveying the give-and-take of individual focus in performance as piano, bass, horns, percussion, and human voice express mood and feeling. Though this professional production is well-rehearsed, singers and instrumentalists undoubt-edly explored one another’s individual strengths in the rehearsal process, allowing for each per-former’s “personal stamp” to shine through in key moments. Both the descendant of old forms of music and the ancestor of modern styles of music, jazz unites past with present, present with future. Its organized patterns provide a framework for individual and collective improvisation, experimentation, and creative expression. Jazz great Wynton Marsalis summed up the multifaceted nature of jazz by saying, “As long as there is democracy, there will be people wanting to play jazz because nothing else will ever so perfectly capture the democratic proc-ess in sound. Jazz means working things out musically with other people. . . . It teaches you that the world is big enough to accommodate us all.”

Jazz group featuring Wynton Marsalis (left), Willie

Nelson (center), and Norah Jones (right)

7

Classroom Activities

8

Harlem Renaissance 1. With a partner or a small group, select one aspect of the Harlem Renaissance for further study. Consider literature, visual arts, music, or even politics as a jumping-off point; then explore the art-ists and works of that time and place. Who were the major players in that arena? From where did they come? How did they end up in Harlem? With whom did they interact? As you gather infor-mation about the people involved, look also at their works. Prepare a multimedia presentation of photos, images, or music to share, or stage readings of poems or essays. Share your work with your class. 2. Read poetry and stories that evoke images of the Jazz Age. Some suggested authors include Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Zora Neale Hurston, and Ralph Ellison. Then examine visual works by Harlem Renaissance-era artists such as Palmer Hayden and Aaron Douglas. Using quotations that evoke visual images, create a painting, collage, drawing, or other representa-tion of the quotation, setting, or mood evoked by the writing. In sharing your artistic works with your class, explain, too, the inspiration and the choices you made to illuminate that inspiration. Jazz Music 1. Attend a jazz performance or listen to recordings of jazz music. With the guidance of your mu-sic teacher or other leader well-versed in music, identify examples of give-and-take of the lead line, syncopated rhythms, improvisation, and other qualities of jazz music. 2. Explore jazz-related styles of ragtime, Dixieland, zydeco, and rhythm-and-blues, listening to ex-amples and sharing the traits of each style with your classmates. When and where did these forms of music develop? What groups of people influenced the development of these forms of music? What connection is there between heterogeneous societies and cultural traditions of expression? Discuss with your class the issues of “preservation” and “innovation” with regard to cultural heri-tage and contemporary expression. 3. With a group of fellow musicians, take a piece of classical or other traditional music and see if you can explore it musically in a jazz style. Examine how syncopating a line, changing the tempo, or using different instruments than those classically used might create more of a jazz sound. Make use of at least one idea from each member of the group in exploring and creating your jazz version of a piece.

4. Select one of the following jazz musicians, or choose one of your own interest, and research his/her background. How did this person get introduced to music? What innovations did this per-son bring to music, or for what type of work is he/she acclaimed? Find recordings and share them in a presentation to your class. --Louis Armstrong --Ella Fitzgerald --James P. Johnson

--Wynton Marsalis --Harry Connick, Jr. --Herbie Hancock

(continued)

Classroom Activities (continued)

5. Explore the history of the music recording industry with respect to the role of technology. Exam-ine the early cylinder and disc records and players, the innovations in tape and digital recording, and the role of radio in promoting and/or inhibiting music sales through the years. With this information, engage in a point-counterpoint discussion with your classmates regarding one or more of these top-ics:

—Should radio stations pay music producers to play songs on the radio? —Should music producers pay radio stations to promote their songs or concert tours? —Should the public be required to pay to listen to music on the radio?

A twist on this idea: explore the financial side of making, promoting, and selling music in the re-cording industry nowadays, learning what a performer earns from each track downloaded from iTunes, Amazon, or other music site. Where does the money go if it doesn’t all go to the performer? Discuss with your class the fairness of the financial side of the music business from the perspectives of the artists, producers, and consumers.

9

Above, sounds of a jazz trio

go out to radio audiences

across the country. Right,

78rpm record of a popular

hit from the Jazz Age.

Sources “Ain’t Misbehavin’: Additional Facts.” Music Theatre International. Accessed 3/18/14 at https://www.mtishows.com/show_detail.asp?showid=000002. Bates, Karen Grigsby. “Fats Waller’s Playful Piano Legacy.” National Public Radio. September 28, 2006. Accessed 3/18/14 at http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6156065. Burns, Ken. Introduction to documentary series Jazz. Accessed 3/18/14 at http://www.schooltube.com/video/da5afb547587515d9796/Ken-Burns-JAZZ-Intro. “Faces of the Harlem Renaissance: Fats Waller.” The Kennedy Center Artsedge. Accessed 3/18/14 at http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/interactives/harlem/faces/fats_waller.html. “Fats Waller.” New Grove Dictionary of Jazz. Oxford University Press. Accessed 3/18/14 at PBS.org, site http://www.pbs.org/jazz/biography/artist_id_waller_fats.htm. “Fats Waller Forever.” Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University Libraries. Copyright 2002. Ac-cessed 3/19/14 at http://newarkwww.rutgers.edu/ijs/fw/fatsmain.htm. “Harlem Renaissance.” The History Channel. Accessed 3/19/14 at http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/harlem-renaissance/videos#. “Harlem Renaissance Walking Tour.” Neal Shoemaker, narrator. C-Span video. July 2001. Ac-cessed 3/20/14 at http://www.c-span.org/video/?165632-1/harlem-renaissance-walking-tour. Hughes, Langston. “Juke Box Love Song.” Accessed online 3/19/14 at http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/juke-box-love-song/. Oppenheim, Mike. “The Harlem Renaissance and American Music.” All About Jazz, March 3, 2013. Accessed 3/20/14 at http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=44023. Samuelsson, Marcus. “Is Harlem ‘Good’ Now?” New York Times online. February 15, 2014. Ac-cessed 3/20/14 at http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/16/opinion/sunday/is-harlem-good-now.html?_r=0. Smith, Joan. "Wynton Blows His Horn For Jazz", San Francisco Examiner and Chronicle. Dec. 18, 1994, p. C-17, as retrieved from http://www.allaboutjazz.com/articles/arti1200_15.htm on 9/15/09.

10

Photo and Image Credits

Page 2— “Drawing in Two Colors” Artist: Winold Reiss. Source: United States Library of Con-gress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3g05687. Public domain. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Weinold_Reiss_-_Drawing_in_two_colors.jpg. Page 3—Fats Waller. Photographer: Alan Fisher, New York World Telegram and Sun. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c23107. Per deed of gift to LOC, no known restrictions. Accessed online at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fats_Waller_edit.jpg. Page 3—Photo of framed “Stormy Weather” poster. Photographer: Johanna Schloss, taken with permission of Cab Calloway School of the Arts, Wilmington, DE. March 27, 2014. Page 5—Zora Neale Hurston. Source: New York World Telegraph & Sun, donated to Library of Con-gress. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c08549. No known restrictions. Accessed at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zora_Neale_Hurston_NYWTS.jpg. Page 5— The Apollo Theatre. Author: Beyond My Ken. GNU Free Documentation License and Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 3.0 License. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apollo_Theatre_from_west.jpg. Page 5—Savoy Theatre plaque. Author: Lukeholladay. Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 3.0 Unported License. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Savoyplaque_large.jpg. Page 5—Langston Hughes. Photographer: Carl Van Vechten. Source: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004663043. Public domain. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Langston_Hughes_1936.jpg Page 5—Map of Harlem. Map data © 2014 Google. Print permission according to terms of fair use. Page 7—Jazz group featuring Wynton Marsalis, Willie Nelson, and Norah Jones. Author: Anthony Quintano (Quintanomedia.com). Creative Commons 2.0 Attribution Generic License. Accessed at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Willie_Nelson_Wynton_Marsalis_and_Norah_Jones_(cropped).JPG. Page 9—Jazz trio at Hurricane Ballroom. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs. Public do-main. Source: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/fsa.8d13203. Accessed at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Duke_Ellington_-_Hurricane_Ballroom_-_trio.jpg. Page 9—Victor Record of “Mood Indigo.” Author: Freimut Bahlo. Public domain. Accessed at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Duke_Ellington_orchestra_mood_indigo.jpg.

11

Why Go to the Theatre? State and National Education Standards Addressed Through

Taking Your Students to a Live Theatre Production When your students view live theatre, they are taking part in a learning experience that engages their minds on many levels. From simple recall and comprehension of the plot of a play or mu-sical to analysis and evaluation of the production elements of a show, students receive and interpret messages communicated through words, movement, music, and other artistic devices. Beyond “I liked it; it was good,” students learn to communicate about the content and performance of an artistic piece and to reflect on their own and others’ emotional, aesthetic, and intellectual points-of-view and responses. And the imme-diacy of live theatre--the shared moments between actors and audience members in the here-and-now--raises students’ awareness of the power and scope of human connection.

The following educational standards are addressed in a visit to a performance at Dela-ware Theatre Company along with a pre-show DTC classroom presentation and post-show talkback session at the theatre. (Additional standards addressed through the use of the study guide or through further classroom study are not included here.) Common Core English Language Arts Standards: Reading: 9-10 and 11-12, Strands 3, 4, 6 Language: 9-10 and 11-12, Strands 3, 4, and 5

National Standards in Theatre Education (AATE/ETA): Grades 5-8: CS 6a, 6c, 6d; 7a, 7b, 7c; 8a, 8c; 8d Grades 9-12: CS 6a, b; Adv. 6b; 7a, 7b, 7c, 7d; Adv. 7e, 7f; 8a, 8c, 8d

Delaware Standards for English Language Arts (DOE): Standard 2: 2.2a, 2.4bl, 2.5b, 2.5g, 2.6a Standard 3: 3.1b, 3.3b1, 3.3b2 Standard 4: 4.1a, 4.1b, 4.1c, 4.2f, 4.3a, 4.4b

Delaware Standards for Visual and Performing Arts—Theatre (DOE): Standard 6: 6.4, 6.5 Standard 7: 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 7.5, 7.6 Standard 8: 8.3, 8.4

The following are additional standards addressed by study guide lessons for Ain’t Misbehavin’: Delaware Standards for Music Standard 3: 3.1, 3.10 Standard 6: 6.4, 6.9

Delaware Standards for Social Studies: History Strand Standard 4: 9-12 a

Compiled by Johanna Schloss, Associate Director of Education & Community Engagement, Delaware Theatre Company, 2014

12

![Show Tunes - Blowhole Buskersblowholebuskers.weebly.com/uploads/5/5/4/6/55461743/show_tunes... · Show Tunes . AIN'T MISBEHAVIN' [C] ... Ain't mis [A7] behavin' [Dm] savin' all my](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/5aade01e7f8b9a190d8b6c37/show-tunes-blowhole-bu-tunes-aint-misbehavin-c-aint-mis-a7-behavin.jpg)