Dejan Bulić, The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and the Early Byzantine Period on the Later...

-

Upload

dejan-bulic -

Category

Documents

-

view

94 -

download

22

Transcript of Dejan Bulić, The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and the Early Byzantine Period on the Later...

-

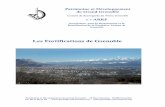

THE WORLD OF THE SLAVS

Studies on the East, West and South Slavs: Civitas, Oppidas, Villas and Archeological Evidence

(7th to 11th Centuries AD)

-

Reviewers:Academician Jovanka Kali

Prof. Vlada StankoviAssist. Prof. Dejan Radievi

Milan Radujko, Ph.D.Lovorka orali, Ph.D.

This book has been published with the financial support of THE MINISTRY OF THE EDUCATION, SCIENCE AND TEHNOLOGICAL

DEVELOPMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA(project No III 47025)

-

THE INSTITUTE OF HISTORY

MonographsVol. 64

Tibor ivkovi Dejan Crnevi, Dejan BuliVladeta Petrovi, Irena Cvijanovi, Bojana Radovanovi

THE WORLD OF THE SLAVSStudies on the East, West and South Slavs:

Civitas, Oppidas, Villas and Archeological Evidence (7th to 11th Centuries AD)

Editor in chiefSran Rudi, Ph.D.

Director of The Institute of History

Belgrade2013

-

TABLE OF CON TEN TS

PrefaceList of Abbreviations

The Urban Landcape of Early Medieval Slavic Principalities inthe Territories of the Former Praefectura Illyricum and in theProvince of Dalmatia (ca. 610 950)TIBOR IVKOVI

The Architecture of Cathedral Churches on the Eastern AdriaticCoast at the Time of the First Principalities of South Slavs (9th 11thCenturies)DEJAN CRNEVI

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and the Early ByzantinePeriod on the Later Territory of the South-Slavic Principalities,and Their Re-occupationDEJAN BULI

Terrestrial Communications in the Late Antiquity and the EarlyMiddle Ages in the Western Part of the Balkan PeninsulaVLADETA PETROVI

The Typology of Early Medieval Settlements in Bohemia, Polandand RussiaIRENA CVIJANOVI

The Typology of Slavic Settlements in Central Europe in theMiddle Ages According to Latin Sources (8th 12th Centuries)BOJANA RADOVANOVI

List of ReferencesList of IllustrationsGeneral Index

913

15

37

137

235

289

345

369413421429

-

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and the EarlyByzantine Period on the Later Territory of the South-Slavic Principalities, and Their Re-occupation

DEJAN BULI

As the title reveals, this text will cover the Early Byzantine period(early 5th early 7th century) in the areas we have surveyed ourselves, i.e.Serbia, Croatia and Montenegro. However, as some authors use the twodesignations the Late Antiquity and the Early Byzantine period synony-mously, the time frame for the territories of Bosnia and Herzegovina, andMacedonia is set from the 330s to 610s. It was already pointed out that aprecise chronological estimate cannot be determined without excavationworks and analysis of ceramics and small findings.184 The sites indexedwith poor, often just unspecific data, and described in acquired, conservativeinterpretations, offer insecure datings, making fine-tuned chronologicalestimations impossible, most of the time. For all these reasons, a revisionof the already-existing lists of sites for the territories of Macedonia andBosnia and Herzegovina could not be done, as the material was impossibleto gain insight into.

Considering territory, the work will cover the area of the formerYugoslavia, without Slovenia and Istria, or more precisely, the area delim-ited by the river Raa on the north, i. e. Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina,Montenegro, Serbia, and Macedonia. In other words, the territories that

184 M. Garaanin, Odbrambeni sistemi u praistoriji i antici na tlu Jugoslavije,Materijali 22, Novi Sad 1986, 10; I. remonik, Rimska utvrenja u BiH sosvrtom na utvrenja kasne antike, Arheoloki Vestnik 41 (1990) 355 (=remonik, Rimska utvrenja).

3

-

first formed a part of South Slavic principalities, and then states, during theEarly Middle Ages. During the research undertaken until now in this area,a large number of fortifications were noticed, with a cultural layer fromthe Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine period. Information on these was,in a large measure, obtained through terrain reconnaissance. Sondageswere undertaken on dozens of sites, while systematic archaeological exca-vations were seldom conducted. The territory covered in this workencompasses geographical entities defined according to the present-dayadministrative borders of the states, which is why we did not take intoaccount the provincial demarcations from the Late Antiquity/EarlyByzantine period, as these present-day territories were part of two, threeor several provinces throughout the Late Antiquity.185

After the creation of lists and maps of the Late Antiquity/EarlyByzantine localities, the final objective of this work is registering the EarlyMedieval and Medieval strata in the mentioned fortifications, and ondetecting potential continuity and discontinuity that marked the medievaland Early Byzantine period. It is difficult to report some of the relevantdata about the construction or particularities of specific fortifications, theirfunctions, interconnections, and the roles they played in the defence systemof the Empire in the Late Antiquity or the Early Byzantine era. The aim of thisresearch is to reflect on the historical context, and not on the movable archae-ological material, which is a task beyond the scope of this kind of study.

Some zones of present-day countries remain insufficiently covered,a consequence of local museums policies and interest, because of whichsome areas have not even been reconnoitred, which caused uneven levelof exploration among the regions. For example, the regions of continentalCroatia are the least examined territory.

All that was mentioned above pertains to medieval sites, too, and toa far greater degree, as they were neglected. They were not the subjects ofinitiated projects, but have always remained out of the focus of researchersto such a degree that these days clear distinction between the LateAntiquity and Early Byzantine ceramics is no longer made, and themedieval strata are not even registered.

138 Dejan Buli

185 Issues regarding precise delineations of the Late Antiquity provinces havenot been considered relevant for this work.

-

The Province of Dalmatia A Historical Overview

With the Hunnic invasion, the majority of Illyrian towns weredestroyed.186 The decline of Roman-Byzantine towns, together with therestricted means of artisanal industry and trade, led to these townsbeing reduced to well-fortified settlements with entirely rural agglom-eration. The centre shifted towards the south, to the settlements whosecrisis could be alleviated by an influx of agrarian population fleeing thebarbarians.187

The new circumstances, which emerged from the crisis of the thirdcentury, led to the reforms of Diocletian and Constantine the Great, butultimately to the division of the Empire in 395. During the reign of theOstrogoths, Dalmatia retained the basic structure of its earlier ogranization,but with one novelty: the merger of Dalmatia and Savia into one adminis-trative unit that had its centre in Salona.188 Salona was an archiepiscopalsee; the existence of Dalmatian dioceses is known because of the presenceof bishops at the ecclesiastical councils in Salona in 530 and 533, whichalso provided a delimitation of the province of Dalmatia.189 But it remainsunknown whether organization of dioceses was preserved after 537, whenByzantium pushed the eastern Goths out of Dalmatia, early on in the con-flict between Byzantium and the Goths. As follows from the ecclesiastical

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 139

186 For further information on the history of towns in the mid-400s Illyricum,cf.: Prisci fragmenta (ed. L. Dindorf), Historici graeci minoris I, Lipsiae1870, Frg. 2, 280.20-281.6; Frg. 8, 291.9-15; I, 7-16; . , , 2000, 59-60 (= , ). Thefollowing works offer a wider account of this problem: D. S. Potter, TheRoman Empire at Bay, AD 180-395, London 2004; A. Cameron, The LaterRoman Empire, AD 284-430, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1993; S. Mitchell,A History of the Later Roman Empire, AD 284-641: The Transformation ofthe Ancient World, Hoboken, New Jersey 2007.

187 For further information regarding the process of disintegration andruralization in the hinterland of Illyricum, and the archaeological traces itleft, see: . , 5. 7. , Sirmium ( ), 2003,239- 258; , , 58-66.

188 . , j , 1957, 23-24 (= ,j ).

189 Diplomatiki zbornik kraljevine Hrvatske s Dalmacijom i Slavonijom I(ured. I. Kukuljevi Sakcinski), Zagreb 1874, No. 239 and No. 240.

-

policy of Justinian I, he strived to reshape the borders of archdioceses so asto match the borders of dioceses to those of provinces.190 Salona held its sta-tus as an archdicese, because Dalmatia was part of the Diocese of Illyricumin the Late Empire period, with its seat in Salona.191

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and the Early Byzantine Period

Bosnia and Herzegovina occupies the central part of the Balkans.It borders with Croatia on the north, north-west and south, by the riversSava and Una, and the Dinarid mountains, Serbia on the east and north-east, by the river Drina, and Montenegro on the south-east. Bosnia andHerzegovina accesses the Adriatic Sea on the south, through the coastalmunicipality of Neum.

The very name of Bosnia and Herzegovina reveals the duality ofthis land. The major part of northern, peri-Pannonian Bosnia belongs tothe southern rim of the Pannonian Basin, except for the area around theriver Sava, including Semberia, which is an extension of the PannonianPlain. Northern Bosnia is marked by a predominantly mountainous terrainwhich slopes northwards from the south.192 The mountain areas of Bosniaand Herzegovina represent a wide expanse, part of the Dinarid mountainrange with high and medium mountains, as well as with long and deep,often canyon-like valleys, between them. Fields of karst are by far morenumerous than basins. Eastern parts of Bosnia have karst depressions, ratherthan karst fields.193

Geographically speaking, two units can be discerned inHerzegovina: the upper or mountainous pastoral Herzegovina, and thelower or Adriatic agricultural Herzegovina, situated in the south.194 Themountainous Herzegovina represents the south-eastern extension of the

140 Dejan Buli

190 . , ( ), 2004, 41-42 (= , ).

191 For the entire issue on the province of Dalmatia and its eastern borders, see:, , 33-49.

192 , , 151-152.193 , , 489-490.194 . . , , 1972, 495

(= , ).

-

western Bosnian high karst, land with mountain ridges and karst fieldslying between.195 The maritime Adriatic region expands into the lowerHerzegovina, along the lower course of the river Neretva, its tributariesand the great karst field known as Popovo polje.196

In hydrographical terms, the greatest part of Bosnia andHerzegovina belongs to the Black Sea drainage basin, i.e. to the river Savabasin, with the Una, Vrbas, Bosna and Drina rivers as its longest tributaries,all flowing parallely from the south towards the north.197 A small area ofHerzegovina drains into the Adriatic Sea, with Neretva being the longestriver. Surface rivers are prevalent in northern and central Bosnia, whilesubterranean rivers flow through western Bosnia and the mountainousregions of Herzegovina.198 The lower Herzegovina is distinguished byrivers, lost rivers, springs, surface and subterranean lakes and wetlands.During the humid seasons of the year, karst fields become temporary lakes,often large and deep.199

A moderate continental climate is characteristic of northernBosnia, while the sub-alpine climate is prevalent in the wider Dinara area.The lower Herzegovina has the Adriatic climate, which is a variation of analtered Mediterranean type of climate, influencing the mountainous regionsof Herzegovina as well, due to the proximity of the Adriatic coast.200

During the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine period, the present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina approximately encompassed the hinterland ofthe province of Dalmatia (Dalmatiae), as well as parts of the provincesPannonia Prima (Pannonia I) and Pannonia Secunda (Panonnia II).

Excavations confirmed Patschs hypothesis that castra were erectedin Doboj and ipovo (several, since castra lying on the road Salona-Servitium were confirmed by the sources),201 in the aftermath of thePannonian uprising in the first century AD. The forms of ceramic findingsfrom the castrum of Doboj dated from the first to the fifth century,202 aswas confirmed by a test excavation conducted at ipovo.203 In those early

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 141

195 , , 496-497.196 , , 806-807.197 , , 152.198 , , 490.199 , , 812.200 , , 490, 811.201 C. Patsch, Zbirka rimskih i grkih starina u bos.-herc. Zemaljskom muzeju,

Sarajevo 1915, 57 (= Patsch, Zbirka).202 I. remonik, Rimski kastrum kod Doboja, GZM 39 (1984) 70.203 remonik, Rimska utvrenja, 355.

-

days, the important crossings on the tiver Sava were doubtlessly well-protected, which in time developed into the Sava limes,204 but, not a singlefortification on the Sava has been discovered, let alone excavated, up to thepresent.

Information about the movable findings are available for very fewsites, especially for the medieval ones, since published material is absent,most of the times, despite long archaeological excavations in Bosnia andHerzegovina, initiated at the end of the 19th century.205

Irma remonik composed a list of 263 Roman fortifications, withemphasis on ones form the Late Antiquity. Most of these fortifications,considering they are mainly in the highlands, were built in the LateAntiquity or Early Byzantine period.206 But a certain number of them werenot indexed in the Lexicon: 79, 92, 93, 94, 100, 108; and some sites wereidentified as prehistoric strongholds (gradine): 44, 65, 69, 70, 105; or as atumul: 90. Site 106 was identified as a prehistoric (gradina) and a medievaltown; site 104 as a prehistoric stronghold and a Turkish tower, while sites28 and 30 were identified as medieval towns. We assume that in theseexamples, the author probably obtained information inaccessible to us,which led him to classify these sites as antique fortifications. But a fewsites remain problematic, as they do not appear to have been strongholds:sites 25, 83 and 114; and it would be reasonable to omit from the list site42 (a Roman camp deserted in the third century), site 89 (identified as aRoman structure) and the site 203 (classified as a medieval necropolis).207

Another six sites mentioned in Perica pehars list of 60 fortifica-tions from the Early Byzantine period,208 should be added to the list of 263sites composed by I. remonik and incorporated into her work:209

204 Patsch, Zbirka, 159.205 For further information regarding the history of the undertaken research,

see: Arheoloki leksikon Bosne i Hercegovine 1, Sarajevo 1988, 15-49 (=Leksikon).

206 remonik, Rimska utvrenja, 355-364. 207 Leksikon 2-3.208 The register of the fortifications, to economise space, was attached to the list

of I. remonik: remonik, Rimska utvrenja, 355-364. 209 pehar compiled his register without having taken into account the work

written by I. remonik: . , ( ), 5, 2008, 17-48 (=, ).

142 Dejan Buli

-

264. Gradina, Rajike, Glamo210

265. Gredine, Potoani, Livno211

266. Mareljia gradina, Staro selo-Carevica, Glamo212

267. Gradina, Prisoje-Perkovii, Duvno213

268. Gradina, Podgradina, Livno214

269. Teferi, Krupac, Ilida215

The aforementioned list should be expanded with several othersites mentioned in the Archaeological Lexicon of Bosnia and Herzegovina.These probably represent fortifications dating from the Late Antiquity orEarly Byzantine period and include the following:216

270. Crkvena, Kamiani, Prijedor217

271. Velika Gradina, Donja Slabinja, Bosanska Dubica218

272. Vracarevo (Vracar-grad), Brievo, Prijedor219

210 , , 42; Leksikon 3, 240; A. Benac, Utvrena ilirskanaselja I. Delmatske gradine na Duvanskom polju, Bukom blatu, Livanjskomi Glamokom polju, Sarajevo 1985, 158-160 (= Benac, Ilirska naselja).

211 , , 42; Leksikon 3, 242; Benac, Ilirska naselja, 103-104.212 , , 42; Leksikon 3, 245-246; D. Sergejevski, Putne biljeke

iz Glamoa, GZM 54 (1942) 153; Benac, Ilirska naselja, 180-181.213 , , 42; Leksikon 3, 266; V. Radimsky, Starine kotarska

upanjog u Bosni, GZM 6 (1894) 300; Benac, Ilirska naselja, 21.214 M. Mandi, Gradine, gromile i druge starine u okolini Livna, GZM 47 (1935)

12; , 42; Leksikon 3, 239. 215 , , 42; Leksikon 3, 57; . ,

, , 2003, 103; D. Sergejevski, Arheoloki nalazi uSarajevu i okolici, GZM 2 (1947) 46-48.

216 The deficiencies of this classification are evident; a considerable number ofthese forts were categorized only after surface findings, collected duringreconnaissance. Scarce information from the Lexicon often omit potteryfindings, while the chronological classification is most often given with asimple, broad phrase Late Antique fortification.

217 Leksikon 2, 34.218 Leksikon 2, 39.219 V. Radimsky, O nekojim prehistorijskim i rimskim graevnim ostacima u

podruju rijeke Sane u Bosni, GZM 3 (1891) 439-440; D. Sergejevski,Epigrafski nalazi iz Bosne, GZM 12 (1957) 112-116; D. Sergejevski, Rimskirudnici eljeza u sjeverozapadnoj Bosni, GZM 18 (1963) 88-92; Leksikon2, 39.

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 143

-

273. Mali Grad-Blagaj kod Mostara.220

274. Cetinac, Bokovii, Laktai221

275. Lisiji Brijeg-Cintor, Laminci, Bosanska Gradika222

276. Gradac, Trnovica, Zvornik223

277. Veliki Gradac, Ostojievo, Bijeljina224

278. Zvornik 1, Zvornik225

279. Crkvena, Dragoaj, Banja Luka226

280. Gradina, Brdo-Rudii, Mrkonji Grad227

281. Gradina, Bosansko Grahovo228

282. Gradina, Drvar Selo-Glavica, Drvar229

283. Velika Gradina, Lastve-Rakovice, Bosanski Petrovac230

284. arampovo, Gornji Vakuf231

285. Babunar (Saraj), Travnik232

286. Blace, Rankovii, Pucarevo233

144 Dejan Buli

220 . Basler, Arhitektura kasnoantikog doba u Bosni i Hercegovini, Sarajevo1972, 50 (= Basler, Arhitektura).

221 Leksikon 2, 48.222 L. eravica - Z. eravica, Arheoloka nalazita u okolini Bosanske Gradike,

Zbornik Krajikih muzeja 6, Banja Luka 1974, 220-221; Leksikon 2, 52.223 Leksikon 2, 91.224 C. Patsch, Mali rimski nahoaji i posmatranja, GZM 9 (1897) 518; Leksikon

2, 98.225 M. Babi, custodian of the museum in Bijeljina, has confirmed the existence

of an Early Byzantine layer by means of sondage, of which he was kind tolet us know. . Mazali, Zvornik (Zvonik). Stari grad na Drini, GZM Istorijai etnografija 10 (1955) 73-116; D. Kovaevi-Koji, Zvornik (Zvonik) usrednjem vijeku, Godinjak drutva istoriara BiH 16, Sarajevo 1967, 19-35;Leksikon 2, 98.

226 Leksikon 2, 128.227 Leksikon 2, 146.228 I. remonik, Dva srednjovekovna grada u okolici Grahova, GZM 8 (1953)

349-351; Leksikon 2, 161.229 V. uri, Starine iz okoline Bosanskog Petrovca, GZM 14 (1902) 252; Z. Vinski,

Kasnoantiki starosjedioci u salonitskoj regiji prema arheolokoj ostavtinipredslavenskog supstrata, VAHD 69, 1967 (1974) 41; Leksikon 2, 162.

230 V. uri, Starine iz okoline Bosanskog Petrovca, GZM 14 (1902) 22-23;Leksikon 2, 165-166.

231 J. Petrovi, Novi arheoloki nalazi iz doline Gornjeg Vrbasa, GZM 15-16(1960-1961) 1961, 231-234; Basler, Arhitektura, 84; Leksikon 2, 186.

232 P. A. Hoffer, Nalazita rimskih starina u travnikom kotaru, GZM 7 (1895) 50(= Hoffer, Nalazita); J. Koroec, Travnik i okolina u predhistorijsko doba,GZM 4-5 (1949-1950) 1950, 254-265 (= Koroec, Travnik); Leksikon 2, 195.

233 Leksikon 2, 195.

-

287. Glavica, Mali Mounj, Vitez234

288. Gradac (Tarabovac), Vilenica, Travnik235

289. Gradina-Megara, Gole, Travnik236

290. Grbavica Brdo, Grbavica, Vitez237

291. Jankovii, Jankovii, Travnik238

292. Oblak, Mali Mounj-Divljaci, Vitez239

293. Trojan, Pazari, Hadii240

294. Domavia, Gradina-Sase, Srebrenica241

295. Rade, Neum. Sitomir, Radiii, Ljubuki242

296. Veliki vrh, Romanija, Sokolac243

297. Veliki Gradac, Presjeka-Mahinii, Nevesinje244

298. Brijeg, Pareani, Bilea245

299. Gradina, Brova, Trebinje246

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 145

234 Koroec, Travnik, 257; Leksikon 2, 197.235 Koroec, Travnik, 256; Leksikon 2, 198.236 Koroec, Travnik, 250; Leksikon 2, 199.237 Hoffer, Nalazita, 54; Koroec, Travnik, 259; Leksikon 2, 199.238 Koroec, Travnik, 265; Leksikon 2, 200.239 Koroec, Travnik, 258; D. Sergejevski, Novi i revidirani rimski natpisi, GZM

6 (1951) 309; Leksikon 2, 203.240 Leksikon 3, 57.241 L. Pogatschnig, Stari rudokopi u Bosni, GZM 2 (1890) 125-130; V.

Radimsky, Rimski grad Domavija u Gradini kod Srebrenice u Bosni itamonji iskopi, GZM 3 (1891) 1-19; F. Buli, Rimski nadpisi u Srebrenici(Municipium Domavia), GZM 3 (1891) 387-390; V. Radimsky, Prekopavanjeu Domaviji kod Srebrenice godine 1891., GZM 4 (1892) 1-24, C. Patsch,Prilozi naoj rimskoj povjesti, GZM 22 (1910) 1911, 192-195; D. Sergejevski,Epigrafski i arheoloki nalazi (ipovo, Livno, Duvno), GZM 42, sv. 2 (1930)162-163; D. Sergejevski, Rimski natpisi iz Bosne, uikog kraja i Sandaka,Spomenik SKA 93, Beograd 1940, 144; I. Bojanovski, Biljeke iz arheologijeI, Nae Starine 19 (1964) 193; I. Bojanovski, Arheoloki pabirci sa podrujaantike Domavie. lanci i graa za kulturnu istoriju istone Bosne, Tuzla1965, 103; Leksikon 3, 69.

242 C. Patsch, Mali rimski nahoaji i posmatranja, GZM 9 (1897) 528-529;Leksikon 3, 334.

243 . Truhelka, Prethistorijske gradine na Glasincu, GZM 3 (1891) 306-307;Leksikon 3, 108.

244 D. Sergejevski, Rimska cesta na nevesinjskom polju, GZM 3 (1948) 55; I.Bojanovski, Prilozi za topografiju rimskih i predrimskih komunikacija inaselja u rimskoj provinciji Dalmaciji (s posebnim obzirom na podrujeBosne i Hercegovine). II - Prethistorijska i rimska cesta Narona - Sarajevskopolje s limotrofnim naseljima, Godinjak Akademije nauka i umetnostiBosne i Hercegovine 17, Sarajevo 1978, 90-91; Leksikon 3, 153.

245 Leksikon 3, 170.246 Leksikon 3, 177.

-

300. Velika Gradina, Slivnica, Trebinje247

301. Vraevica, Panik, Bilea248

302. Grad Lis, Repovci, Konjic249

303. Gradac, Glavatievo, Konjic250

304. Ilina, Gorani, Konjic251

305. Velika Gradina, Varvara, Prozor252

306. Anelia (Juria) Gradina, Lipa, Livno253

307. Gradina, Podgradina, Livno254

308. Gradina (Nuhbegovia gradina), Podhum, Livno255

309. Kasalov Gradac, Livno256

310. Brina, Vinjani, Posuje257

311. Bukovac 2, itluk, Posuje258

312. Grad, Stipanii, Duvno259

313. Gradina, Korita, Duvno260

146 Dejan Buli

247 . Odavi, Praistorijska nalazita na prostoru Trebinja (gomile i gradine),Tribunia 4, Trebinje 1978, 153; Leksikon 3, 195.

248 I. Bojanovski , Arheoloki spomenici, Nae starine 8 (1962) 12; Leksikon 3, 196.249 P. Aneli, Historijski spomenici Konjica i okoline, Konjic 1975, 158-160 (=

Aneli, Historijski spomenici); Leksikon 3, 213.250 P. Aneli, Srednjovekovni gradovi u Neretvi, GZM 13 (1958) 200-202;

Leksikon 3, 213.251 Aneli, Historijski spomenici, 29; Leksikon 3, 217.252 V. uri, Gradina na vrelu Rame, prozorskog kotara, GZM 12 (1900) 99-

118; . Truhelka, Kulturne prilike Bosne i Hercegovine u doba prethistorije,GZM 26 (1914) 79-80; B. ovi, Prelazna zona, Praistorija Jugoslovenskihzemalja 4 (1983) 390-412; N. Mileti, Rani srednji vijek, Kulturna istorijaBosne i Hercegovine od najstarijih vremena do pada ovih zemalja podosmansku vlast, Sarajevo 1984, 422; Leksikon 3, 225.

253 V. uri, Arheoloke biljeke iz Livanjskog kotara, GZM 21 (1909) 169-170; M. Mandi, Gradine, gromile i druge starine u okolini Livna, GZM 47(1935) 9-10; A. Benac, Utvrena ilirska naselja, I. Delmatske gradine naDuvanskom polju, Bukom blatu, Livanjskom i Glamokom polju, Sarajevo1985, 134 (= Benac, Ilirska naselja); Leksikon 3, 235.

254 Leksikon 3, 239.255 V. uri, Arheoloke biljeke iz Livanjskog kotara, GZM 21 (1909) 169;

Benac, Ilirska naselja, 80-83; Leksikon 3, 239-240.256 M. Mandi, Gradine, gromile i druge starine u okolini Livna, GZM 47 (1935)

7; Benac, Ilirska naselja, 108-110; Leksikon 3, 244.257 Leksikon 3, 260.258 P. Ore, Prapovjesna naselja i grobne gromile, GZM 32 (1977) 1978, 218-219 (=

Ore, Naselja); Leksikon 3, 261.259 Leksikon 3, 264.260 N. Mileti, Ranosrednjovekovna nekropola u Koritima kod Duvna, GZM 33

(1978) 1979, 141-204, . Miki, Rezultati antropolokih ispitivanja ranosre -

-

314. Vukove Njive, Gradac, Posuje261

315. Bilobrig, Vionica, itluk262

316. Gradina, Mali Ograenik-Donji Ograenik, itluk263

317. Krstina, Hamzii, itluk264

318. Mala Gradina, apljina265

319. Milanovaa, Gorica, Grude266

320. Trebinje-Crkvine267

With these additions, we reach a total of 320 fortifications, mainlyfrom the Late Antiquity or Early Byzantine period. This figure still doesnot reflect their real quantity, with all the already mentioned deficienciesof such a classification and some zones having been poorly explored, but itis certainly closer to the actual number. The empty zones were not unin-habited in the Late Antiquity, for these were the mining districts of east-ern Bosnia or the fertile valleys around the Bosna river. A lot of strong-holds (gradine) were, with inertia, were dated of as prehistoric. But evenif we accept such datings, there remains a number of Late Medieval townswhose Late Antiquity or Early Byzantine phase can be assumed to exist.The conjectured density of fortifications can be glimpsed at by comparingthe empty zones with the surrounding ones.

Since the historical information being absent and the adequatearchaeological information being scarce, it is difficult to speak of the his-torical context beyond general observations. The process of adapting to thenew circumstances unfolded in two directions. The first was fortifying thealready existing settlements in the plains, as seen in Mogorjelo at apljina,where an agricultural estate was fortified already in the early fourth century.The other direction, far more efficient, is the so-called vertical migration resettlement to the fortifications on higher altitudes.268

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 147

dnjovekovne nekropole u Koritima kod Duvna, GZM 33 (1978) 1979 205-222; Benac, Ilirska naselja, 74-76; Leksikon 3, 264-265.

261 Ore, Naselja, 184-185; Leksikon 3, 279.262 Leksikon 3, 290.263 . Belagi, Steci. Kataloko topografski pregled, Sarajevo 1971, 315 (=

Belagi, Steci); Leksikon 3, 297.264 Leksikon 3, 301.265 C. Patsch, Pseudo-Skylaxovo jezero. Prinos povjesti donjeg poreja Neretve,

GZM 18 (1906) 374-376 (= Patsch, Pseudo-Skylaxovo); Leksikon 3, 330.266 Patsch, Pseudo-Skylaxovo, 379; Leksikon 3, 331.267 . , 7. 10. , 2007, 158 (=

, ).268 , , 37.

-

But this does not exclude the possibility that the exploitation of fer-tile plains, suitable for agricultural production, could have continued. Wecan speak of a more large-scale fortification construction in the hinterlandof Dalmatia only after 535 and the final expulsion of the Goths fromDalmatia, since it is unlikely that during their reign they would allow livingin strongholds.269 Besides, the number of the known fortifications in con-tinental Croatia is, so far, meagre.

Perica pehar divided the fortifications in four big groups, based ona sample of 60 fortifications from Late Antiquity or Early Byzantine period,according to their surface area: big, middle-sized and small, while the forti -fications with an unknown surface made a group of its own.270 Small forti -fications, in the hinterland of Dalmatia, represent the most numerous group.

As ihajlo ilinkovi warned, when classifying the fortificationsaccording to their size, one should be aware that, most of the times, theouter extensive ramparts often remained undiscovered, and that theycould have been used occasionally to keep the livestock during the siege.271

pehars division may be accepted, but it should be borne in mindthat all the fortifications on high altitudes were located on more or lesssteep slopes. When making a projection of a ground plan, which is normal-ly executed on a horizontal plane, shrinking of the surface area unavoid-ably happens, in line with the laws of mathematics.272 But the conclusionsthat the big-sized fortifications, erected on the elevations overlooking thefertile plains, rivers or fields, acted as a sort of collective centres in addi-tion to having a defensive role, and maybe even that of ore storages-remain dubious.273 One of the main functions the fortifications had wasprobably the protection of the mining basins and auriferous rivers.

148 Dejan Buli

269 Procopius makes no mention of fortification construction in Dalmatia.270 The first group is made up of fortifications with a surface area greater than

1 hectare; the second of fortifications with a surface area between 0.5 and 1hectare; while the fortifications of a surface area smaller than 0.5 hectarefall into the third group: , , 19.

271 . , . - , 2010, 225-226.

272 In order to take the measurements of the surface area, it is necessary to havein mind the shrinkage that occurs when projecting terrain onto a flathorizontal plane, except for where there are no slopes and the surfaceremains the same. Practically, this would mean that the represented surfaceof the fortification is 86.6% of the real one, if the angle of the slope is 30;and only 70.7%, if the angle of the slope is 45. It is an entirely differentquestion if some surfaces are useful due to these terrain slopes.

273 , , 38.

-

Findings of slag indicate that the fortifications were erected in the vicini-ty of the mining shafts, and the residues of slag are frequently found onmany sites, regardless of their geographical position or size, as had beensuggested. The idea that the discovered buildings had the function ofhoreum (silo for storage of agricultural products) has no foundation.

Positions these fortifications occupied could determine their maintasks and functions; however, the excavations carried out in or aroundthese sites so far do not yield sufficient elements that could make a corre-lation between the surface of a fortification and its function. The crucialfunction of the fortifications situated along the main roads was to securethe traffic, settlements or river crossings. Besides the insufficient researchon the fortifications and the deficient knowledge of the traffic ways (espe-cially the less significant ones), additional difficulty lies in the locations ofa majority of Roman settlements that we know of from the sources,remaining unidentified.274

On the other hand, perceived clusters of fortified points along theborder of the maritime Adriatic belt and on the mountain massifs thatseparated the coastal regions from the hinterland of Dalmatia are spuriousas well.275 We think that such attitude comes, doubtlessly, from the insuffi -cient research of the given areas that led to the false clusterization of thefortified points. Also, without understanding that these generally repre-sented fortified villages,276 with no military function, this theory should berejected. Nevertheless, the unquestionably higher density of fortifications

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 149

274 remonik, Rimska utvrenja, 357.275 Other than the local functions - protection of roads and settlements - the

fortifications around Bosanski Petrovac, Grahovo, Livanjsko polje,Glamoko polje, Duvanjsko polje, Posuje, Gruda, Imotsko polje, Ljubukopolje, and those lying along the lower course of Neretva, formed a solidbarrier towards the hinterland; See: remonik, Rimska utvrenja, 357.

276 In the last couple of years, an opinion prevailed that most of thefortifications served as fortified settlements, without excluding additionalfunctions. The nature of the archaeological findings confirms thishypothesis, since these have been predominantly associated withcraftsmanship and agriculture, and there are objects pointing to thepresence of women and existance of churches, all indicating a longer staywithin the forts. Cf: . , , , - 2002, 71-72; . , , III, 2005, 180; . , . , 2010, 227.

-

comes as a consequence of geographic conditions i.e. the fact that thesewere erected on a low, coastal stretch of land which led some inhabitantsto leave the area for the island fortifications, and the majority to flee to thehighlands of the Dinara mountains. Most likely such process of recedingwas happening on the northern side of the massif as well.

The following, revised list, includes the fortifications that, besidesthe already mentioned Late Antique/Early Byzantine strata, contain medievaltraces that indicate a continuous or re-initiated use of the fortification. 277

1. Brekovica, Biha (95)278

2. Zecovi, arakovo, Prijedor (81)279

3. Grad, Gornji Vrbljani, Klju (Velika and Mala Gradina (80)280

4. Gradina (Grad), Gradac, Posuje (46)281

5. Zelengrad, Han Kola-utkovci, Banjaluka (134)282

150 Dejan Buli

277 The number within the parentheses designates the number of the site,corresponding to the number on the provided map.

278 Leksikon 2, 14. Some authors date the remains of ramparts and of thepentagonal tower only to the Late Antiquity and the Early Byzantineperiod: V. Radimsky, Nekropola na Jezerinama u Pritoci kod Bia, GZM 5(1893) 41; P. pehar, Late Antique and Early Byzantine Fortification inBosnia and Herzegovina (Hinterland of the Province of Dalmatia),Hhensiedlungen zwischen Antike und Mittelalter-Ergnzungsbnde zumReallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, Band 58, Berlin NewYork 2008, 586 (= pehar, Late Antique).

279 The foundations of the church, as well as the sporadic medieval objectsconfirm that these fortifications were used in the Middle Ages: Leksikon 2,39; I. remonik, Rimski ostaci na Gradini Zecovi, GZM 11 (1956) 137-146;Basler, Arhitektura, 55.

280 The occupation continued into the Carolingian age (8th 9th century). Thatis confirmed by the archaeological findings such as the ceramics of EarlySlavonic type, a bronze spur and a gold-plated prong of a belt buckle:Leksikon 2, 144; Z. Vinski, Novi ranokarolinki nalazi u Jugoslaviji, VjesnikArheolokog muzeja u Zagrebu 10-11 (1977-78) 1979, 143-190; I.Bojanovski, Kasnoantiki katel u Gornjim Vrbljanima na Sani, GZM 34(1979) 1980, 109-119.

281 In some of the researched structures on the slopes of gradina were noticedmaterial remains of the Early Medieval period (the Slavic period): Leksikon3, 264.

282 Remnants of the wall above the Late Antique fortification are thought to berelated to the town of Zemljanik, mentioned in the sources from the late13th century: . , ,GZM 48 (1936) 33. West of the plateau, a necropolis arranged in rows wasdiscovered and categorized as medieval: Leksikon 2, 133.

-

6. Mogorjelo, apljina (252)283

7. Biograci, Litice, Mostar (37)284

8. Gradac, Hudutsko, Prozor (29)285

9. Gradina, Bivolje brdo, apljina (263)286

10. Grad Biograd, Zabre, Konjic (24)287

11. Blagaj (Stjepan Grad), Blagaj, Mostar (35)288

12. Vidoki Grad, Stolac (191)289

13. Gradina, Alihode, Travnik (68)290

14. Crkvina, Makljenovac, Doboj (73)291

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 151

283 Besides the necropolis dating from the Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages,on the fortified site and in its immediate surroundings human habitation inthe Early Middle Ages was confirmed with the medieval ceramics and EarlyCarolingian findings. Several tombstones (steci) have also been preserved,so the archaological findings cover the period from the eighth to fifteenthcentury; . Werner, Ranokarolinka pojasna garnitura iz Mogorjela kodapljine (Hercegovina), GZM 25-26 (1961) 235-242; Z. Vinski, O nalazimakarolinkih maeva u Jugoslaviji, SP 11 (1981) 9-54; Z. Vinski, Zurkarolingischen Schwertfunder aus Jugoslawien, Jahrbuch des Rmisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 30 (1983) 465-501; Leksikon 3, 331.

284 This fortification was again used during the eighth and ninth centuries; bya population of Slavic characteristics, but under Frankish influence, asconfirmed by the discovered spur: I. remonik, Rimsko utvrenje naGradini u Biogracima kod Litice, GZM 42/43 (1989) 89-92.

285 The use of Gradac in the Middle Ages has been confirmed by the findingsof Late Medieval ceramics: Leksikon 3, 213.

286 Discovered movable findings represent pre-historic and Roman ceramicsand bricks, so it remains unclear why a medieval settlement was evenmentioned: Leksikon 3, 325.

287 This site was mentioned in 1444, 1448 and 1454 as the domain of HerzegStjepan. In the Turkish census of 1469, it was mentioned as a deserted town,while the square (trg, a suburb) of the same name had 17 houses: Leksikon3, 213; P. Aneli, Historijski spomenici Konjica i okoline, Konjic 1975,125-129 (= Aneli, Historijski spomenici).

288 The earliest source that explicitly mention the town dates back to 1423. TheTurks took the town in 1465 and in the eighteenth century the walls of thisstructure were once again redesigned. What particularly draws attention isa twelfth-century stone plate with a cyrillic inscription, in a secondary use:Leksikon 3, 290-291.

289 This town was mentioned for the first time in the fifteenth century and itwas destroyed later, during the construction of Austro-Hungarian barracks:Leksikon 3, 195; Basler, Arhitektura, 50-51.

290 A fragment of Early Medieval (Slavic) ceramics was discovered in the areaof Gradina: Leksikon 2, 198.

291 During the Middle Ages, there was a wooden church on the hilltop with gravesaround it dated from the ninth to thirteenth centuries: Leksikon 2, 63.

-

15. Bobovac, Dragovii-Miljakovii, Vare (63)292

16. Gradac, Homolj, Kiseljak (59)293

17. Gradina, Dabravina, Vare (171)294

18. Teferi, Krupac, Ilida (269)295

19. Crkvena, Kamiani, Prijedor (270)296

20. Bosanska Gradika, Bosanska Gradika (113)297

21. Lisiji Brijeg-Cintor, Laminci, Bosanska Gradika (275)298

22. Zvornik 1, Zvornik (278)299

23. Gradina, Bosansko Grahovo (281)300

292 For the first time Bobovac was mentioned in 1350, while a royal court wasbeing built from the second half of the fourteenth to the mid-fifteenthcentury. The Turks took it in 1463: P. Aneli, Bobovac i Kraljeva Sutjeska.Stolna mesta bosanskih vladara u XIV i XV stoleu, Sarajevo 1973; Leksikon3, 15. For further information regarding remains from the Early Byzantineperiod, see: . Basler, Kanelirani stup iz Stoca, Slovo Gorina 10, 1982, 52-53.

293 Besides one medieval ceramic vessel, graves dated to the Middle Ages werediscovered above the Early Byzantine basilica: Leksikon 3, 19. pehar claimsthat these tombs have to be dated to the Late Antiquity: pehar, LateAntique, 573. V. Skari, Altertmer von Gradac in der Lepenica (Bosnien)(Starine na Gracu u bosanskoj Lepenici), GZM 44 (1932) 1-21.

294 Individual medieval findings were found inside the Gradina. These includeseveral objects made of iron and a trefoil arrow, dated to the Early MiddleAges. The issue of dating these objects to the Antiquity or the Middle Agesremains open: D. Sergejevski, Bazilika u Dabravini (Revizija), Sarajevo 1956;I. Nikolajevi, Kasnoantike presvoene grobnice u srednjovekovnojcrkvenoj arhitekturi Bosne i Hercegovine, Predslavenski etniki elementi naBalkanu u etnogenezi Junih Slovena, Sarajevo 1969, 223-227. I. Nikolajevi,Oltarna pregrada u Dabravini, ZRVI 12 (1970) 91-112; For a moregeneralized overview, see: Leksikon 3, 19.

295 D. Sergejevski and K. Topolovac claim that this was a late medieval fortifi -cation: D. Sergejevski, Arheoloki nalazi u Sarajevu i okolini, GZM 2, (1947)46; Leksikon 3, 57, while M. Popovi and P. pehar support the theory ofLate Antique/Early Byzantine fortification: , ,103; pehar, Late Antique, 586.

296 Leksikon 2, 34.297 E. Paali, Antika naselja i komunikacije u Bosni i Hercegovini, Sarajevo

1960, 27; L. eravica - Z. eravica, Arheoloka nalazita u okolini BosanskeGradike, Zbornik Krajikih muzeja 6, Banja Luka 1974, 215-233 (= eravica- eravica, Arheoloka nalazita); G. Kraljevi, Rimski novci iz BosanskeGradike i Laktaa, GZM 34 (1978) 1979, 137.

298 eravica - eravica, Arheoloka nalazita, 220-221; Leksikon 2, 52.299 Leksikon 2, 98; . Mazali, Zvornik (Zvonik). Stari grad na Drini, GZM

Istorija i etnografija 10 (1955) 73-116; D. Kovaevi-Koji, Zvornik (Zvonik)u srednjem vijeku, Godinjak drutva istoriara 16, 1967, 19-35.

300 I. remonik, Dva srednjovekovna grada u okolici Grahova, GZM 8 (1953)349-351; Leksikon 2, 161.

152 Dejan Buli

-

24. Glavica, Mali Mounj, Vitez (287)301

25. Gradina-Megara, Gole, Travnik (289)302

26. Kastel- Banja Luka (76)303

27. Veliki vrh, Romanija, Sokolac (296)304

28. Grad Lis, Repovci, Konjic (302)305

29. Gradac, Glavatievo, Konjic (303)306

30. Velika Gradina, Varvara, Prozor (305)307

31. Gradina (Nuhbegovia gradina), Podhum, Livno (308)308

32. Gradina, Korita, Duvno (313)309

33. Vukove Njive, Gradac, Posuje (314)310

34. Gradina, Mali Ograenik-Donji Ograenik, itluk (316)311

301 Koroec, Travnik, 257; Leksikon 2, 197.302 Koroec, Travnik, 257; Leksikon 2, 197; Belagi, Steci, 145; Leksikon 2, 199.303 In the thirteenth century, Banja Luka belonged to the upa Zemljanik and

the oblast (area) of Donji Kraji. Its modern name was mentioned for the firsttime in 1494. After the fall of the Bosnian state (1463), Banja Luka becamea part of the banovina of Jajac, and the Turks took it in early 1528: A. Bejti,Banja Luka pod turskom vladavinom, Nae Starine 1 (1953) 91-116; V.Skari, Banja Luka i njena okolina u davnini, Otabina 31-33 (1924), 2;3;2;I. remonik, Kastel Banja Luka. Gradina sa slojevima od praistorije dodanas, AP 14 (1972) 133-134; L. eravica, Kastel Banja Luka. Kompleksnoutvrenje, AP 15 (1973) 112-113; B. Graljuk, Posavina u antici u svjetlunovih istraivanja, Antiki gradovi i naselja u junoj Panoniji i graninimpodrujima, Varadin 1977, 147-154; Banja Luka, Enciklopedija Jugoslavije1, A-Biz, Zagreb 1980, 492-494 (M. Vasi); Leksikon 2, 130; D. Peria,Zlatnik cara Justinijana iz Banjaluke, GZM 45 (1990) 171-176.

304 Leksikon 3, 108.305 Aneli, Historijski spomenici, 158-160; Leksikon 3, 213.306 P. Aneli, Srednjovekovni gradovi u Neretvi, GZM 13 (1958), 200-202;

Leksikon 3, 213.307 V. uri, Gradina na vrelu Rame, prozorskog kotara, GZM 12 (1900) 99-

118; N. Mileti, Rani srednji vijek, Kulturna istorija Bosne i Hercegovine odnajstarijih vremena do pada ovih zemalja pod osmansku vlast, Sarajevo1984, 422; Leksikon 3, 225.

308 V. uri, Arheoloke biljeke iz Livanjskog kotara, GZM 21 (1909) 169; A.Benac, Utvrena ilirska naselja, I. Delmatske gradine na Duvanskom polju,Bukom blatu, Livanjskom i Glamokom polju, Sarajevo 1985, 80-83;Leksikon 3, 239-240.

309 N. Mileti, Ranosrednjovekovna nekropola u Koritima kod Duvna, GZM 33(1978) 1979, 141-204; . Miki, Rezultati antropolokih ispitivanjaranosrednjovekovne nekropole u Koritima kod Duvna, GZM 33 (1978)1979, 205-222; Benac, Ilirska naselja, 74-76; Leksikon 3, 264-265.

310 Leksikon 3, 279.311 Leksikon 3, 297.

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 153

-

35. Mali Grad-Blagaj near Mostar (273)312

36. Grad Vitanj, Kula, Sokolac (106)313

37. Gradina Loznik, Podloznik, Pale (104)314

38. Gradina Bokaevac, Kostajnica, Konjic (28)315

39. Gradina, Vraba, Bijela, Konjic (30)316

40. Vrtine, rvanj, Ljubinje (203)317

41. Trebinje-Crkvine (320)318

This leads us to the conclusion that out of 320 Late Antique/EarlyByzantine sites, medieval traces appear on 41 sites, or 12.81%. We holdthis percentage to be much higher in reality, which can be deduced if we bearin mind the deficiencies and scarcity of information, because of whichmedieval horizons are impossible to discern.

And since the sites taken into account here were often merelyregistered in the process of reconnaissance, or yielded only scarce andinaccurately dated findings, a wider picture and chronological frame ofthese sites has proved very complex to grasp. The absence of writtensources and infrequent occurrence of the remaining architecturalmonuments add to the complexity of this task, as well.

A more accurate dating of certain fortifications has not beenestablished beyond them being medieval towns: 1, 23, 31, 36, 38, 39; somerepresented a medieval town with a church in it: 2; or a medieval town anda necropolis: 5. When it comes to site 18, only a broad conclusion can bemade that it belongs to the Middle Ages. Sites 20 and 21 were classified as

154 Dejan Buli

312 About 2.5 km from the fortification of Blagaj near Mostar, stands MaliGrad, formed of a tower, what was probably a cistern, and anotherbuilding. The ground floor of the tower corresponds with the time ofEmperor Justinian I: Basler, Arhitektura, 50.

313 remonik, Rimska utvrenja, 360; Leksikon 3, 96.314 Belagi, Steci, 263; remonik, Rimska utvrenja, 360; Leksikon 3, 54.315 remonik, Rimska utvrenja, 358; Aneli, Historijski spomenici, 163-167;

250-255; Leksikon 3, 215.316 remonik, Rimska utvrenja, 358; P. Aneli, Srednjovekovni gradovi u

Neretvi, GZM 13 (1958) 185-189; Aneli, Historijski spomenici, 129-133;Leksikon 3, 215.

317 Belagi, Steci, 379; remonik, Rimska utvrenja, 361; Leksikon 3, 196.318 Archaeological excavations confirm existence of a town, about 1.2 ha in

surface area. Accidental pottery findings point to the Early Byzantineperiod the seventh century, as well as to the period between the ninth andtenth centuries: . , 7. 10. , 2007, 158 (= , ).

-

medieval settlements; site 19 as a medieval building, while individualmedieval findings were discovered on several sites: 16, 17, 24. Slightlymore precise designations were provided for sites 8, 10, 12, 15, 22, 26, 28?,29? as Late Medieval towns; site 33 was classified as a Late Medieval set-tlement; the following sites were identified as Late Medieval necropoles:32, 34, 40; site 25 as a tombstone; site 11 was dated to the Late Medieval,Ottoman period; site 37 was identified as a Turkish tower. Site 14 was aindentified as church with a necropolis, dated between the 9th and 13th

centuries.According to Slavic and Early Carolingian findings, the following

sites were defined as Early Medieval: 3, 4, 6, 7, 13; site 30, which represent asettlement with a necropolis, was also dated to the Early Medieval period.Site 9 was dated to the Middle Ages, for unknown criteria; site 27 wasdestroyed during later construction works, which might corroborate thehypothesis that it dates back to the Middle Ages.

Years after the fall of Salona represented the beginning of a newage, one of continuous Slavic settlement in the decades that followed. Inthe second wave of migrations, with the emperors consent, the Serbs andthe Croats got hold of the entire area of the former province of Dalmatia,where the first principalities would rise some time later. About them weknow from the treatises of Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos.319

Byzantine coastal towns and some islands were the only ones spared of theconquests and they will play an important role in Christianization and thedevelopment of Slavic hinterland.320

There is almost no historical information on the events in Bosniaand Herzegovina during the first couple of centuries after the Slavic colo-nization, and the archaeological insights hardly provide a more profoundperspective. Opportunities were not taken adequately, just because manysites with these remains were either excavated too early at the turn ofthe century, or too late destroyed before being researched.

Why the architectural elements attributed to the Slavs are difficultto recognize will be discussed later; for now, it will suffice to acknowledgetheir presence in the strongholds (gradine). During excavation of the

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 155

319 Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De administrando imperio I (ed. Gy.Moravcsik R. J. H. Jenkins), Washington DC 1967, cc 31-36 (= DAI).

320 , , 309.

-

fortifications, fragments of early Slavic ceramics were discovered. Thesefindings reflect the attitude of the Slavs towards their new environment,but the use of these sites is not an evidence for the adaptation of the new-comers to the earlier settlements, nor is it a proof for the continuity of life.However, it is a proof of analogous factors that led to the fortificationsbeing re-used immediate war danger, in this case. Purposely chosen andsituated on important strategic points, they justified the reason of theirchoice and affirmed their centuries-long importance.

The first to mention Bosnia was Constantine Porphyrogenitos inthe mid-tenth century, when it was still a part of Serbia, while other landslying within the province of Dalmatia were principalities of the Narentines,Zachlumia and Travunia, ruled by archonts. Salines (in the vicinity of thepresent-day Tuzla) was included as well, among other Serbian towns,whereas only two towns in Bosnia were mentioned, Katera and Desnik.321

Katera was thought to be Kotorac near Sarajevo, but this site has nomedieval strata whatsoever; it could have been Kotor, in the middle of theVrbanje upa (administrative unit). It has been known under the name ofBobac (Bobos), but all that is known of the town pertains to the LateMiddle Ages. The location of Desnik remains unidentified, but it wasthought to be located near the present-day Deanj.322 Alternatively, if wefollow the understanding that the term kastra oikoumena in De adminis-trando imperio, the treatise of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos, does notdesignate inhabited towns, but lists the towns in the ecclesiastical organi-zation of the Roman church, these two towns might be Bistua (Zenica orVitez) and Martar (Mostar or Konjic).323

Porphyrogenitos mentions five towns in Travunia: Trebinje, Vrm,Risan, Lukavete and Zetlivi;324 in Zachlumia aside from Bona and Hum,another five: Ston, Mokriskik (Mokro), Josli (Olje), Galumajnik andDobriskik;325 and among the Narentines (Pagans) the towns of Rastoka andDalen (Doljani). Risan is a well-known coastal town in Montenegro. Trebinjewas founded at the site of the present-day Crkvine, over an earlier Romanfortification. Accidental findings of pottery were dated to the Early

156 Dejan Buli

321 DAI I, 32.149-151.322 ,

2010, 183.323 T. ivkovi, On the Beginnings of Bosnia in the Middle Ages, Spomenica

akademika Marka unjia (1927-1998), Sarajevo 2010, 177-178. 324 DAI I, 34.19-20.325 DAI I, 33.20-21.

-

Byzantine period and the 7th century, and fragments from the 9th - 10th cen-turies were found next to the ramparts.326 The position of Vrm has not beenestablished yet, but it is being searched for around the Trebinjica rivereast of Trebinje (maybe around Panik). Lukavetija and Zetlivija have notbeen localized with certainty.327

Bona and Hum were, in all likelihood, located at the site of Blagajbeside Mostar. Smaller forts were erected on two hilltops, Stjepan grad andMala gradina, outside which settlements existed probably already in theEarly Middle Ages, which corresponds to the reports by ConstantinePorphyrogenitos on these two towns.328

In the tenth century, Bosnia was a part of the Serbian realm, ruledby prince aslav. And it seems that after his death, in the mid-tenth cen-tury, Bosnia broke off and became politically independent.329 At the closeof the century, it was subjugated by the Bulgarian tsar Samuil, and after-wards became a part of the Byzantine Empire. Throughout the 11th century,Bosnia, Travunia and Zachumlie were under the authority of the Docleanstate. From the mid-twelfth century, Bosnia was under the supreme ruleof Hungary, followed by a brief return to Byzantium. Then began a newage for Bosnia and Herzegovina that would last until the Ottoman conquestof Bosnia in 1463, and of Herzegovina in 1481.330

In all these times of war, the fortifications were more or less used,but as no systematic excavations took place until today, it is guesswork tosay when and under what circumstances were some of them sites of waroperations, which are proven by remains of weapons and traces of fire onsome of the sites.

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 157

326 , , 158.327 For further information regarding the proposed ubications, see: . ,

II ( ). , 48 (1880) 1-152; ., , 37(1998) 20-21; . Loma, Serbischen und kroatisches Sprachgut bei KonstantinPorphyrogennetos, 38 (1999/2000) 87-160; T. , ConstantinePorphyrogenitus Kastra oikoumena in the Southern Slavs Principalities, 57 (2008) 9-28 .

328 Basler, Arhitektura, 50; Leksikon 3, 290-291 .329 , , 57.330 For a general chronological frame of the development of Bosnia, see: .

, I, 1940; . , , 1964.

-

Croatia

Most of the present-day Croatia belonged to the province ofDalmatia, with the exception of the northern, flat areas that were parts ofthe Upper and Lower Pannonia, i.e. the provinces of Savia and PannoniaII. Byzantine presence in Slavonia remains dubious. On the section oflimes from Aquincum to Singidunum, distance of several hundred kilome-tres, no Roman camp was discovered, not even in Mursa.331 The only relictof urban life from the Late Antiquity is Siscia (Sisak), the town that sur-vived until the early eighth century.332

Geographically speaking, the province of Dalmatia can be dividedinto two areas, the coastal and the mountainous region. In the present time,the coastal area belongs to Croatia, except for Neum. The littoral karstregion is characterized by a jagged coastline, shortage of drinking water,and a few arable, fertile fields. There are only few passages fit for travel inthe high, insurmountable mountains immediately beyond the coastline.Only two existed through the mountain Velebit the northern one,through which Senj was connected with the Iapyd lands in the present-dayLika and with Sisak; and the southern one, which connected Lika withRavni Kotari. Except for these, the passage from Klis to Sinjsko polje led inthe same direction as did the communication line along the Neretva river.333

Roman roads built in the early first century AD, immediately afterthe conquest of these lands, facilitated the control and the process ofRomanization in Dalmatia and Illyricum. The proximity of the Adriaticseaports made the delivery of material and goods, required by the army,convenient. A string of permanent Roman camps was erected in the areastretching from the Krka to the Neretva rivers, and south of the Dinaramountain. Among these, only two legion camps stood: Burnum andTilurium, while auxiliary camps were based in Promona, Magnum,

158 Dejan Buli

331 M. Sanader, Rimske legije i njihovi logori u hrvatskom dijelu panonskoglimesa, Opuscula archaeologica 27 (2003) 463-468.

332 B. Miggoti, Arheoloka graa iz ranokranskog razdoblja u kontinentalnojHrvatskoj, Od nepobjedivog sunca do sunca pravde. Rano kranstvo ukontinentalnoj Hrvatskoj, Zagreb 1994, 47.

333 J. J. Wilkes, Dalmatia, London 1969, XXI-XXVII.

-

Andetrium and Bigeste.334 After the conquest of Dalmatia, the populationcame down from strongholds (gradinas) into the plains and foothills,where antique settlements developed. Antique settlements, which existeduntil the fourth century were situated near a moderately hilly terrain, onslightly lifted terraces in the middle of fertile plains, close to the sources offresh water and yet safe from seasonal floods.335

In the turbulent times of the Late Antiquity, these prehistoriclocations were revived and turned once again into fortified settlements.The frequent barbarian incursions that move in from the north and usedthe roman roads forced the endangered and decimated population to seekprotection in these fortified sites that then evolved into genuine settle-ments. This pattern of life became a habit out of necessity, not becausethese sites served as shelters, which they did not. The process of the so-called horizontal migration took place in the coastal region of Dalmatia, inwhich the inhabitants of the coastal area moved to the islands and main-tained contacts with the mainland via the sea.336

Within the class of fortifications from the Late Antiquity, focusin Croatia was only on the fortifications erected on promontories andtowering heights of certain islands, and in similar locations on the coastline. Some of these structures were built on uninhabited islands, or in loca-tions far from any settlements, which led to the conclusion that they werenot built for defensive purposes, but that they together formed a systemthat was meant to ensure full control over seafaring on the eastern coast ofthe Adriatic. Their position to each other and to the main seafaring routesbetween the islands and along the coast point to this, too.337

Zlatko Gunjaa classified the Late Antique fortifications on thecoastline and on the islands. Besides the fortifications he assorted withutter certainty, he also mentioned the positions in which remains of forti-

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 159

334 D. Peria, Je li delmatsko podruje presjekao rimski limes?, ArchaeologiaAdriatica 2 (2008), 507; I. Borzi - I. Jadri, Novi prilozi arheolokojtopografiji dugopoljskoga kraja, Archaeologia Adriatica 1 (2007) 167.

335 T. Tkalec, S. Karavani, B. iljeg, K. Jelini, Novootkrivena arheolokanalazita uz rjeicu Veliku kod mjesta Majur i Ladinec, Cris. asopisPovjesnog drutva Krievci 9-1, Krievci 2007, 5-25.

336 . Tomii, Arheoloka svjedoanstva o ranobizantskom vojnomgraditeljstvu na sjeverojadranskim otocima, Prilozi 5/6 (1988/1989), Zagreb1990, 29-53.

337 Z. Gunjaa, Kasnoantika fortifikacijska arhitektura na istonojadranskompriobalju i otocima, Odbrambeni sistemi u praistoriji i antici na tluJugoslavije, Materijali 22, Novi Sad 1986, 124 (= Gunjaa, Kasnoantika).

-

fications allegedly existed (but were yet to be confirmed), some positionswhich he marked based on his own impressions, the importance of thelocations and the potential oversight over seafaring in a wider area.338 Fromthis list and from the fortifications provided by Goldstein,339 here wereincluded only those that underwent archaeological excavations as well asthose where architectural elements have been preserved. Count of thealready-mentioned fortifications from the Late Antiquity/Early Byzantineperiod we added to the fortifications in the hinterland of Dalmatia, as wellas those covered by the latest excavations, to the extent of availability ofmore recent publications:

1. Fortifications on the cape Molunat (15th century)340

2. pidaurus (Cavtat) (up to the 9th century, Late Middle Ages)341

3. Island of Mrkan342

4. Islet of Bobara near Cavtat343

5. Gradac near Dubrovnik344

6. Spilan above upa at Dubrovnik345

7. Dubrovnik (continuity)346

8. Stari Grad in the Peljeac peninsula347

9. Fortifications on St. Micheals hill in Peljeac (church, 11th century)348

160 Dejan Buli

338 Such assumptions are supported, in some cases, by the toponyms of thesesites, or by the continuous presence of fortifications on them, whoseconstruction most probably destroyed previous structures: Gunjaa,Kasnoantika, 128-129.

339 Goldtajn, Bizant.340 L. Bereti, Molunat. Utvrde i regulacioni plan Molunata iz druge polovine

15. stoljea, Prilozi povijesti umetnosti u Dalmaciji 14, Split 1962, 53;Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 128; Goldtajn, Bizant, 34.

341 Sui, Antiki grad, 35; Goldtajn, Bizant, 34.342 I. Fiskovi, O ranokranskim spomenicima neronitskog podruja, Dolina

rijeke Neretve od prethistorije do ranog srednjeg vijeka, Izdanja HAD 5,Split 1980, 243 (= Fiskovi, O ranokranskim); Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 128;Goldtajn, Bizant, 34.

343 Fiskovi, O ranokranskim, 249; Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 128; Goldtajn,Bizant, 34.

344 I. Marovi, Arheoloka istraivnja u okolici Dubrovnika, Anali Dubrovnik 4-5 (1955/1956) 9-31 (= Marovi, Arheoloka istraivanja); Goldtajn, Bizant, 34.

345 Marovi, Arheoloka istraivanja, 24; Goldtajn, Bizant, 34. 346 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 128; Goldtajn, Bizant, 36-37. 347 M. Zaninovi, Antika osmatranica kod Stona, Situla 14/15, Ljubljana

1974, 163-173; Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 125; Goldtajn, Bizant, 38.348 C. Fiskovi, Likovna batina Stona, Anali Dubrovnik 22-23 (1985) 80;

Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 125; Goldtajn, Bizant, 39.

-

10. Polaa in ljet349

11. Katel in Mljet350

12. Fortification in the upper part of the islet of Majsan351

13. Fortification in the site Glabalovo selo above Orebi352

14. Straa above Pjevor in Lastovo353

15. Fortification on the islet of Svetac, near Vis354

16. Gradina above Trpanj in Peljeac355

17. Zamasline in Peljeac356

18. Baina at Ploe357

19. Fortification on the island of Osinje358

20. Gradina in Jelsa359

21. Faros-Starigrad (continuity)360

22. Grad or Galenik on the hill Paljevica, in Hvar361

23. Tor in Hvar362

24. Fort Graee on the exit out of Starigradski bay363

25. Bol on the island of Bra (9th century)364

26. Mirja above Postire in Bra365

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 161

349 M. Sui, Antiki grad na istonom Jadranu, Zagreb 1976, 239.350 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 125351 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 125.352 Fiskovi, O ranokranskim, 230; Goldtajn, Bizant, 39.353 Goldtajn, Bizant, 40.354 B. Kirgin - A. Miloevi, Svetac, Arheo 2, Ljubljana 1981, 45-51; Gunjaa,

Kasnoantika, 125; Goldtajn, Bizant, 40.355 I. Fiskovi, Peljeac u protopovijesti i antici, Peljeki zbornik 1, Zagreb

1976, 15-80; Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 125; Goldtajn, Bizant, 42.356 Fiskovi, O ranokranskim, 221; Goldtajn, Bizant, 42.357 Fiskovi, O ranokranskim, 14-15; Goldtajn, Bizant, 42.358 J. Jelii, Narteks u ranokranskoj arhitekturi na podruju istonog Jadrana,

Prilozi povijesti umjetnosti u Dalmaciji 23, Split 1983, 26-27; Gunjaa,Kasnoantika, 125; Goldtajn, Bizant, 42.

359 Goldtajn, Bizant, 42; M. Kati, Nova razmatranja o kasnoantikom gradu naJadranu, Opvscula archaeologica 27 (2003) 525 (= Kati, Nova razmatranja).

360 On the Croatian coast Faros is the only example of a town from theAntiquity that underwent a reduction in its urban form: Kati, Novarazmatranja, 525; Goldtajn, Bizant, 42-43.

361 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 126; Goldtajn, Bizant, 42.362 Goldtajn, Bizant, 43.363 M. Zaninovi, Neki prometni kontinuiteti u srednjoj Dalmaciji, Materijali

17, Pe 1978, 39-53; Goldtajn, Bizant, 43.364 D. Hrankovi, Braciae insulae descriptio (Opis otoka Braa), Legende i kronike,

Split 1977, 210, 219; Goldtajn, Bizant, 43.365 E. Marin, Mirje nad Postirama, AP 19 (1977) 152-154; Goldtajn, Bizant, 43.

-

27. Salona366

28. Split (Diocletians Palace) (continuity)367

29. Trogir (continuity)368

30. Gradina on the island of irje369

31. Gustijerna on the island of irje370

32. Tradanj on the lower Krka river371

33. St. Ana fortification in the ibenik area372

34. Fortification on the island of Vrgada373

35. reta arac on the island of Kornati374

36. Pustograd on the island of Paman375

37. St. Mihovil in Ugljan376

38. Koenjak near Sala in Dugi otok377

39. Graevina on the islet of St. Peter near Ilovik378

40. Jader (Zadar) (continuity)379

162 Dejan Buli

366 Goldtajn, Bizant, 44.367 Goldtajn, Bizant, 44.368 Goldtajn, Bizant, 44; T. Buri, Vinia. Rezultati rekognosciranja, SP 27

(2000) 59.369 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 126; Z. Brusi, Kasnoantika utvrenja na otocima

Rabu i Krku, Arheoloka istraivanja na otocima Krku, Rabu, i Pagu iHrvatskom primorju, Izdanja HAD 13, Zagreb 1988, 111-119 (= Brusi,Kasnoantika).

370 Z. Gunjaa, Gradina irje. Kasnoantika utvrda, AP 21 (1980) 133; Gunjaa,Kasnoantika, 126; Brusi, Kasnoantika, 111-119.

371 Z. Gunjaa, O kontinuitetu naseljavanja na podruju ibenika i najueokolice, ibenik. Spomen-zbornik o 900. obljetnici, ibenik 1976, 46 (=Gunjaa, O kontinuitetu); Goldtajn, Bizant, 47.

372 Gunjaa, O kontinuitetu, 46; Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 128; Goldtajn, Bizant, 47.373 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 126; Goldtajn, Bizant, 47.374 I. Petricioli, Toreta na otoku Kornatu, Adriatica Praehistorica et Antiqua

(ur. V. Mirosavljevi, et al.), Zagreb 1970, 717-725; Gunjaa, Kasnoantika,126.

375 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 127; Goldtajn, Bizant, 48.376 N. Jaki, Prilozi povjesnoj topografiji otoka Ugljana, Radovi FF-a u Zadru

15 (1989) 83-102; Goldtajn, Bizant, 48; Z. Kara, Tragovi bizantskogurbanizma u Hrvatskoj, Prostor 3-2 (10), Zagreb 1995, 291 (= Kara,Tragovi).

377 . Ivekovi, Dugi Otok i Kornat, Rad JAZU 235 (1928) 256; I. Petricoli,Spomenici iz ranog srednjeg vijeka na Dugom Otoku, SP 3 (1954) 53-65;Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 128; Goldtajn, Bizant, 49.

378 A. Badurina, Bizantska utvrda na otoiu Palacol, Arheoloka istraivanja naotocima Cresu i Loinju, Izdanja HAD 7, Zagreb 1982, 171-174; Gunjaa,Kasnoantika, 128.

379 Goldtajn, Bizant, 49-50.

-

41. St. Damjan fortification in the island of Rab380

42. Katelin fortification above Kamporska draga on the island of Rab381

43. Fortification on the hill of Bosar, near Baka, on the island of Krk382

44. Fortification of Veli Grad on the cape Glavina, on Krk383

45. Fortification on the islet St. Mark (Almis)384

46. Gradina above Omilje, on the island of Krk385

47. Fortification on the islet of Palacol386

48. Apsorus (sor) (Late Middle Ages)387

49. Drid388

50. Island of Drvenik, at the foothill of Graina389

51. Ostrvica in Poljice390

52. Gradina above Modri draga391

53. Sveta Trojica392

54. Gradina above Donja Prizna393

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 163

380 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 127; Brusi, Kasnoantika, 111-119; Goldtajn,Bizant, 51.

381 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 128; Brusi, Kasnoantika, 112; . Tomii, Sv. Jurajiznad Paga. Ranobizantski kastron, Obavijesti HAD 21, Zagreb 1989, 28-31;Kara, Tragovi, 293.

382 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 127; Goldtajn, Bizant, 52.383 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 128; Faber, Osvrt, 116-121; Brusi, Kasnoantika,

112-116; Kara, Tragovi, 291; Goldtajn, Bizant, 52.384 Gunjaa, Kasnoantika, 127; . Faber, Osvrt na neka utvrenja otoka Krka

od vremena prethistorije do antike i srednjeg vijeka, Prilozi 3-4 (1986/1987),Zagreb 1988, 116-121 (= Faber, Osvrt); Brusi, Kasnoantika, 111-119;Kara, Tragovi, 291.

385 N. Novak - A. Boi, Starokranski kompleks na Mirinama u uvali Sapankraj Omilja na otoku Krku, SP 21 (1991) 1995, 32.

386 A. Badurina, Bizantska utvrda na otoiu Palacol, Arheoloka istraivanja naotocima Cresu i Loinju, Izdanja HAD 7, Zagreb 1982, 171-177; Gunjaa,Kasnoantika, 127; Goldtajn, Bizant, 52.

387 In the year of 530, it became the episcopal see: A. Faber, Poeci urbanizacijena otocima sjevernog Jadrana, Arheoloka topografija Osora, Arheoloka istraivanjana Cresu i Loinju, Izdanja HAD 7, Zagreb 1982, 61-78; Goldtajn, Bizant, 54.

388 M. Kati, Utvrda Drid, Prilozi povijesti umjetnosti u Dalmaciji 34 (1994), 5-19.389 T. Buri, Arheoloka topografija otoka Drvenika i Ploe, SP 27 (2000), 41.390 . Rapani, Kasnoantika palaa u Ostrvici kod Gata (Poljica), Cetinska

krajina od prethistorije do dolaska Turaka, Izdanja HAD 8, Split 1984, 149-162.391 . Tomii, Matrijalni tragovi ranobizantskog vojnog graditeljstva u

velebitskom podgorju, Vesnik Arheolokog muzeja 23, Zagreb 1990, 139-162 (= Tomii, Matrijalni tragovi).

392 A. Glavii, Arheoloki nalazi iz Senja i okolice (VI), Senjski zbornik 10-11,Senj 1984, 17; Tomii, Materijalni tragovi, 139-162.

393 Tomii, Matrijalni tragovi, 139-162.

-

55. Kastron in Sutojanica (Svetojanj, Sutojanj, Svetojanica)394

56. St. Juraj above Pag395

57. Fortification on a plateau near Klopotnica396

58. Site Kolja Gromaa north of Novalja397

59. Trinielo near Stara Novalja398

60. Izvor near Kolan399

61. Fortification on the hill of Koljun near Zaglava (Novaljsko polje)400

62. Petri near Stara Novalja401

63. Fortification in Slatina above Gajac402

64. Gradina near Baka voda403

65. Site Luna in the western upper part of the island of Pag404

66. Guard post in the island of Ist405

67. Korintija on in the island of Krk (until the 11th century)406

68. St. Peter peninsula407

69. Beretinova gradina408

70. Hill Pupavica, in the Vuipolje area near Dugopolje409

71. Burnum, the Roman camp410

164 Dejan Buli

394 Tomii, Matrijalni tragovi, 139-162; . Tomii, Svetojanj. Kasnoantikautvrda kraj Stare Novalje na otoku Pagu, Arheoloki radovi i rasprave 12,Zagreb 1996, 291-305.

395 . Tomii, Arheoloka svjedoanstva o ranobizantskom vojnomgraditeljstvu na sjeverojadranskim otocima, Prilozi 5/6 (1988/1989), Zagreb1990, 29-53. A Byzantine gold coin was discovered in one of the rooms: K.Regan, Utvrda Sv. Jurja u Caskoj na otoku Pagu, Prilozi Instituta zaarheologiju u Zagrebu 19 (2002) 141-148 (= Regan, Utvrda). After the fallunder the Slavic control, the settlement kept on living until 1203, when itwas razed and deserted, during a conflict between Rab and Zadar.

396 Regan, Utvrda, 141.397 Regan, Utvrda, 141.398 Regan, Utvrda, 141.399 Regan, Utvrda, 141.400 Regan, Utvrda, 141.401 Regan, Utvrda, 141. 402 Regan, Utvrda, 141.403 Kati, Nova razmatranja, 523.404 Regan, Utvrda, 141.405 Kara, Tragovi, 291.406 Kara, Tragovi, 290.407 Kati, Nova razmatranja, 523.408 . Batovi, Istraivanje ilirskog naselja u Radovini, Diadora 4 (1968) 53-69.409 I. Borzi - I. Jadri, Novi prilozi arheolokoj topografiji dugopoljskoga kraja,

Archaeologia Adriatica 1, Zagreb 2007, 160.410 M. Zaninovi, Burnum, casellum-municipium, Diadora 4 (1968) 121; M.

Zaninovi, Od gradine do castruma na podruju Delmata, Odbrambeni sistemi

-

72. Knin, ancient Ninia411

73. Gradac (above the road leading to Promona), round the St. Marijen church412

74. Danilo Gornji, ancient Ridera near ibenik413

75. Balina glavica (Magnum)414

76. Gradina of Subotie415

77. Podgrae near Benkovac (Aserija) (Middle Ages)416

78. uker in Mokro Polje417

79. Keglevia gradina Mokro Polje418

80. Glavica near the small village of Meter in Lug (Middle Ages)419

81. Kokia glavica Pripolje420

82. Grad on the slopes above Knezovi and Mami jezero421

83. Ljubljan Ravni kotari422

84. Kuzelin near Zagreb423

85. Narona (Vid)424

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 165

u praistoriji i antici na tlu Jugoslavije, Materijali 22, Novi Sad 1986, 166 (=Zaninovi, Od gradine).

411 M. Zaninovi, Kninsko podruje u antici, Arheoloki radovi i rasprave 7,1974, 309; Zaninovi, Od gradine, 167.

412 A. Uglei, Ranohrianska arhitektura na podruju dananje ibenskebiskupije, Drni - Zadar 2006, 51-53.

413 M. Zaninovi, Gradina u Danilu i Tor nad Jelsom, Dva gradinska naselja usrednjoj Dalmaciji, Materijali 15, Beograd 1978, 17-29 (= Zaninovi, Gradina).

414 I. Glava, Municipij Magnum. Raskrije rimskih cestovnih pravaca ibeneficijarska postaja, Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru52, Zagreb - Zadar 2010, 45-59.

415 I. Alduk, Uvod u istraivanje srednjovekovne tvrave Zadvarje (1. dio - doturskog osvajanja), Starohrvatska prosvjeta 32 (2005), 218.

416 Sui, Antiki grad, 136, including the relevant bibliography. Many structureswere dated to the Middle Ages.

417 Life on Gradina ended with the Slavic and Avar incursions, but severalceramic fragments were discovered, dated to the Late Middle Ages: V.Delonga, Prilog arheolokoj topografiji Mokrog Polja kod Knina, SP 14(1984) 259-283 (= Delonga, Prilog).

418 Delonga, Prilog, 259-283. 419 Lj. Gudelj, Proloac Donji. Izvjee o istraivanjima lokaliteta kod crkve Sv.

Mihovila u Postranju, SP 27 (2000) 130. (= Gudelj, Proloac Donji)420 Gudelj, Proloac Donji, 129-146.421 Gudelj, Proloac Donji, 129-146.422 Tomii, Materijalni tragovi, 147.423 This fortification has existed since the 4th century: V. Sokol, Das spatantike Kastrum

auf dem Kuzelin bei Donja Glavica, Arheoloki vestnik 45 (1994) 199-209.424 N. Cambi, Antika Narona. Postanak i razvitak grada prema najnovijim

arheolokim istraivanjima, Materijali 15, Beograd 1978, N. Cambi, Arhitektura

-

86. Gradina Badanj425

87. Bribir (Late Middle Ages, Ottoman period)426

88. Mala Vijola near Knin427

89. itluk near Sinj (ancient veteran colony of Aequum)428

This list enumerates 89 fortifications in Croatia, but this numbermust have been higher. Until now, a plenty of strongholds (gradine) on theterritory of Mokro polje429 and dry-stone fortifications erected on the hillsoverlooking Sinjsko polje have been sighted; some Late Antique/EarlyByzantine ones might be found among the latter.430 Just so, some fortwould surely be registered with sondages on a few of medieval fortifica-tions on the slopes of Medvednica (Medvedgrad, Susedgrad), Samoborskogorje (Oki, Samobor), and umberak/Gorjanac (Mokrice).431 In the vicinityof the already-mentioned Balina Glavica near Umljanovii (75), severalgradinas were discovered, some of which might be from the EarlyByzantine period.432

166 Dejan Buli

Narone i njezina teritorija u kasnoj antici, Radovi Filozofskog Fakulteta uZadru 24 (1984/1985) 33-58; E. Marin, Narona: Vid kod Metkovia, Split 1999.

425 Besides the Late Antiquity period, ranging from the fourth to the sixthcentury, medieval findings were registered, dating from the thirteenth andfourteenth centuries: R. Mateji, Gradina Badanj kod Crkvenice, Jadranskizbornik 10, Pula 1978, 239-271.

426 Z. Gunjaa, Strateko i istorijsko-arheoloko znaenje Bribira, Kolokvij oBribiru. Pregled rezultata arheolokih istraivanja od 1959. do 1965. godine,Zagreb 1968, 9-16; Z. Gunjaa, Nalaz srednjovekovnih arhitektura naBribiru, SP 10, Zagreb 1968, 235-242; T. Buri, Bribir u srednjem vijeku,Split 1987.

427 M. Zaninovi, Kninsko podruje u Antici, Arheoloki radovi i rasprave 7,Zagreb 1974, 303.

428 N. Gabri, Kolonia Claudia Aequum (Pregled dosadanjih iskopavanja,sluajnih nalaza i usputnih zapaanja), Cetinjska krajina od prethistorije dodolaska Turaka, Split 1984, 273-284. The town was mentioned in 533, at thesecond Council of Salona; Sui, Antiki grad, 131.

429 Delonga, Prilog, 262430 D. Peria, Je li delmatsko podruje presjekao rimski limes?, Archaeologia

Adriatica 2 (2008) 511-512; . Barlutovi, Neka pitanja iz povijesti Senja,Senjski zbornik 34 (2007) 265-296.

431 D. Lonjak - Dizdar, Terenski pregled podruja izgradnje HE Podsused,Annales Instituti Archaologici 4 (2008) 109-112.

432 I. Glava, Municipij Magnum. Raskrije rimskih cestovnih pravaca ibeneficijarska postaja, Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru52, Zagreb-Zadar 2010, 45-59.

-

By applying the criteria of urban continuity, Z. Kara proposed thefollowing classification:

- Towns with antique foundations- Dislocated, i.e. abandoned towns- Newly-emerged settlements, some of which lasted continuously433

According to the proposed classification, Zadar (40), partly Trogir(29) and probably Rab, too (41-42) fall into the first type of settlement, i.e.they represent towns with the least turbulent transitions from theAntiquity and Byzantine era to the Middle Ages.434 These towns survivedhistoric calamities, but have persevered up to the present, and are townswith full continuity of existence.

The second group of settlements are those that transferred theirurban functions to more secure areas towards the coast or to the islandswhen the hinterland was lost and the terrestrial communication interrupted.The dwindling population of Salona (27) moved closer to the sea partlyinto Diocletians palace (28), from which the town of Split would develop,and partly towards the nearby Trogir.435 The population of Epidaurus (2)sought refuge on the nearby islands of Mrkan (3) and Bobara (4),436 but alsoto the gradinas of Gradac (5) and Spilan (6), that had already been inhab-ited for centuries before,437 while the episcopal see was transferred toDubrovnik (7). Epidaurus lingered on until the ninth century.438 Narona,an important harbour on the Neretva, was transferred above Ston (8-9)when the lower course of the river silted;439 the same phenomenon struckNin (Aenona) too.

But some ancient cities disappeared completely because new loca-tions could not be found, which happened to a whole string of settlements

The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period 167

433 Kara, Tragovi, 285-298.434 Kara, Tragovi, 285.435 Goltajn, Bizant, 91.436 I. Fiskovi, O ranokranskim spomenicima naronitskog podruja, Dolina

rijeke Neretve od prethistorije do ranog srednjeg vijeka, Izdanja HAD 5,Split 1980, 233, 246, 249; Goldtajn, Bizant, 34.

437 Annales Anonymi Ragusini, Monumenta spectantia historiam Slavorummeridionalium 25, Zagreb 1983, 7; Goltajn, Bizant, 34. For further informationregarding the results of the archaeological excavations, see: I. Marovi,Arheoloka istraivanja u okolici Dubrovnika, Anali Dubrovnik 4-5 (1955-6)24; J. Medini, O nekim kronolokim i sadrajnim znaajkama poglavlja ODalmaciji u djelu Cosmographia anonimnog pisca iz Ravene, Putevi i komuni -kacije u antici, Materijali 17, Pe 1978, 76-77 (= Medini, O nekim kronolokim).

438 Kara, Tragovi, 289.439 Goltajn, Bizant, 96, 98.

-

below Velebit: Ortopla (Stitnica), Vegium (arlobag), Lopsica (urjevo),Argyruntum (Starigrad). These settlements lost their terrestrial communi-cations, and found themselves beyond Byzantine sea routes.440 Senia (Senj)was the only town to have arranged transfer of its location to the castrumof Korinthia on the island coast of Krk (67), which lasted until theeleventh century.441

Late Antique underwent transformations, due to historical eventsand economic factors, political and administrative changes, and newcultural and ideological structures, as analysed in detail by M. Sui.442