Daymon an Empirical Test Ofthe Inequality Trap Concept

-

Upload

alexandra-vasiliu -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of Daymon an Empirical Test Ofthe Inequality Trap Concept

8/3/2019 Daymon an Empirical Test Ofthe Inequality Trap Concept

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/daymon-an-empirical-test-ofthe-inequality-trap-concept 1/3

8/3/2019 Daymon an Empirical Test Ofthe Inequality Trap Concept

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/daymon-an-empirical-test-ofthe-inequality-trap-concept 2/3

The system GMM therefore seems the method best adapted to our

estimation2.

The tests are based on databases over 5 years.3 The sample is

composed of 71 countries over the period 1963 to 2003.

Our model can be written as follows:

yi;t = α yi;t −1 + β X i;t −1 + ui + vi;t ð1Þ

with i =1,…,71 and t = 2,…,9.

With yi,t −1 the dependent lagged variable in the period t −1, X i,t is the set of explanatory lagged variables, ui is the specific individual

effect for each country, vi,t is the specific shock at each period and on

each country.

Where E ⌊ xi;t ui + vi;t

À Á⌋ = 0.

2.2. Justi fication of the choice of variables

Todefine thedependant variable,we used theinequality estimator

EHII (Estimation of the Household Inequality and Inequity) proposed

by Galbraith and Kum (2003) which covers a large number of

countries over a longer period than Deininger and Squire's (1996)

database.4 Thanks to this database, we have a broader representation

of emerging countries in our article (40) than in the majority of

studies. The database being available until 1999, we have determined

the EHII values up until 2003 thanks to the UTIP-UNIDO data supplied

by James K. Galbraith.

According to Galbraith and Kum's (2003) estimations, the most

representative model of inequality is calculated from a Theil index on

wage inequality in manufacturing UTIP-UNIDO,5 but it also incorpo-

rates the share of manufacturing employment in total population,62 It should be noted that Blundell and Bond (1998) Monte Carlo simulations showed

that the system GMM estimator is more ef ficient than the first-differenced one. Indeed

when the number of instruments is small and when there is a finite sample, the first-

differenced GMM estimator is biased. Moreover, it should also be underlined that in

order to validate the use of a GMM model, the estimated coef ficient of the dependent

lagged variable must be larger than that of the within estimator and smaller than that

of the OLS estimator.3

The mean of the variable on each period of 5 years is retained.

4 For a detailed comparison of these two databases, refer to Galbraith and Kum

(2003).5 UTIP-UNIDO: University of Texas Inequality Project–United Nations Industrial

Development Organization. Using data from UNIDO has the advantage that it contains

very little missing data that are perfectly harmonized globally.6

Source: UNIDO.

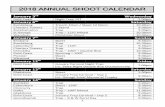

Table 1

Explanatory variables.

Variable Definition Expected sign Role of the variable

Economic and political inequalities

Political

liberty

Rating of political rights from 1 to 7, with 1 representing

the best mark and 7 representing the lowest degree of

freedom (Freedom House (2005)).

pr (+) For Cling et al. (2005) the emergence of an inequality trap can be explained

by political power inequality that leads to the establishment of inequitable

institutions that maintain the inequality situation within the country.

Credit

access

Relation between domestic credit and the gross domestic

product (IMF (2007)).

domcred (−) The assumption made here is that ef ficient markets and access to financial

resources guaranteeing equity are the necessary conditions for combating

inequality traps.

Social and cultural inequalities

Gender

inequality

Share of literate women compared to literate men

between the ages of 15 and 24 (WDI (2007)).

gender (−) This task discrimination based on sex causes a gender inequality which is

passed on to the next generation (Rao, 2006).

Youth literacy

rate

Share of young people between 15 and 24 likely to be

able to read, write and understand a short, simple text

about everyday life (WDI (2007)).

literacyyoung (−) As the WDR 2005 stresses, promoting equity in thefield of human abilities

inevitably involves paying particular attention to very young children.

Population

growth

Annual exponential change in the population actually

present for a given period in a given country (WDI (2007)).

popgrowth (+) The Sarkar (2005) model underlines the role played by population growth

in the persistence of inequalities.

Infantile

mortality

Probability of a child dying before the age of 5 for 1000

children (WDI (2007)).

mortalityyoung (+) According to Deaton (2003) and Lynch et al.'s (2004) studies, the literature

comes to the conclusion that there is a strong correlation between inequality

and mortality.

Table 2

Results of the OLS, within and GMM analyses over a period of 5 years.

Explanatoriesvariables

REG REG Within Within GMM SYS GMM SYS GMM SYS GMM SYS(5 years) (5 years) (5 years) (5 years) (5 years) (5 years) (5 years) (5 years)

t −2 t −2 t −3 t −3

ehiit −1 .791 .798 .390 .299 .599 .479 .602 .515

(18.59) (20.17) (5.05) (5.05) (12.60) (10.02) (12.64) (10.79)

pr t −1 −0.045 −0.141 −0.080 −0.096 −0.098 −0.044 −0.101 −0.069

(−0.38) (−1.36) (−0.51) (−0.71) (−0.79) (−0.66) (−0.419) (−0.57)

domcredt −1 −0.007 −0.009 −0.025 −0.009 −0.019 −0.025 −0.019 −0.024

(−0.92) (−0.14) (−2.15) (−1.07) (−2.21) (−2.68) (−2.15) (−2.64)

gender t −1 020 .013 .020 .020

(1.10) (0.39) (1.19) (1.20)

literacyyoung t −1 −0.007 −0.130 −0.018 −0.019

(−0.71) (−1.21) (−1.72) (−1.78)

mortalityyoung t −1 .012 .047 .029 .029

(1.39) (3.04) (3.21) (3.22)

popgrowtht −1 .269 .198 −0.105 −0.579 .283 .365 .275 .325

(1.25) (1.04) (−0.24) (−1.12) (1.26) (1.72) (1.22) (1.47)

Region 1.43 1.70 2.32

(2.28) (2.43) (1.47)

Cons 7.07 8.91 30.87 24.15 13.32 22.64 13.12 21.32

(2.45) (4.33) (5.67) (7.49) (4.14) (9.27) (4.06) (8.74)

R-squ=0.73;

Adj. R-squ=0.72

R-squ=0.69;

Adj. R-squ=0.68

Within=0.38 Within=0.31 Sargan=0.131

AR(2)=0.843

Sargan=0.147

AR(2)=0.553

Sargan=0.106

AR(2)=0.891

Sargan=0.035

AR(2)=0.567

2 C. Daymon, C. Gimet / Economics Letters xxx (2009) xxx– xxx

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Please cite this article as: Daymon, C., Gimet, C., An empirical test of the inequality trap concept, Economics Letter (2009), doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2009.07.006

8/3/2019 Daymon an Empirical Test Ofthe Inequality Trap Concept

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/daymon-an-empirical-test-ofthe-inequality-trap-concept 3/3

and three dummy variables relative to the Deininger and Squire

(1996) database to harmonize the data. Thefirst one takes the value 0

or 1 depending on whether the inequality index of the country is

based on gross or net income. The value of the second dummy is 0 or 1

depending on whether the calculation is based on household or per

capita income. The last one is equal to 0 when the Deininger and

Squire data are income-based and 1 when they are expenditure-

based. These dummies allow us to solve the problem of the lack of

continuity of the Deininger and Squire database.Taking the ehii variable one period lagged (ehiit −1) enables us to

show the persistence of inequalities over time.

The other explanatory variables chosen7 are described in Table 1.

3. Results

The results are presented in Table 2. This study proves the

influence of equity on inequality persistence, which provides

evidence of inequality traps at an international level (ehiit −1). This

phenomenon is all the more marked in emerging regions as the

dummy variable8 (region) shows. Indeed, the dependent lagged

variable over 5 years hasa significant impact on distribution whatever

methodology is chosen.

We concentrate in particular on the results provided by the GMM

estimation.9 The use of this model is validated because the coef ficient

of this GMM estimated variable is higher than that of the within

estimator and lower than that of the OLS estimator.

When we consider the t −2 and the t −3 periods, the Sargan test

validates the instruments used in the model ( p=0.131, 0.147 and

p= 0.106). Furthermore, the Arellano and Bond (1991) test does

not allow us to reject the assumption of the absence of second order

autocorrelation on the residuals ( p =0.843, 0.553; and p =0.891,

0.567). This study therefore enables us to interpret the estimation's

results correctly.

The influence of the first category of indicators on inequality traps

is underlined. The negative impact of the domcred indicator shows

that low access to financial resources for the most destitute tends to

foster the inequality phenomenon. Since an individual's loan capacity

is linked both to his or her earnings and to his or her initial provisionof wealth, the investment ambitions of the neediest cannot be

fulfilled. However, the pr variable is not significant, meaning that we

cannot draw a conclusion concerning the direct influence of the

institutional environment on inequality persistence.

The second category of variables shows that to put an end to

inequality traps it is necessary to improve the access of the most

destitute to basic needs, notably with regard to health (mortali-

tyyoung ). It would seem therefore that access to health is a sine qua

non condition for beginning a process of equalisation with respect to

the opportunities offered to different groups. The same is true with

regard to demographic transition as results show that population

growth10 ( popgrowth) tends to foster inequalities.

The non-significance of the gender variable does not allow us to

conclude about theimpact of genderinequality on thereproduction of income inequality. It should be noted that what is important in this

variable is specifically discrimination based on sex. When we study

more specifically the elimination of illiteracy among very young

children (literacyyoung ), this variable plays an important role in the

reproduction of inequality. Unless ef ficient education policies are set

up, children from the poorest backgrounds thus have little chance of

benefiting from upward social mobility.

4. Conclusion

The use of a panel data estimation has enabled us to stress thedynamics of inequalites. Our results empirically validate the assump-

tions made by Ferreira and Walton (2005), and confirm that the

economic and sociocultural environmenthave a significant influence on

the reproduction of inequality at a global level. This study should be

complemented by more desagregate and microeconomical analyses

regarding social, political and economic reproduction, and lack of

mobility in order to prove the existence of inequality traps nationally.

Overall, this paper allows us to define the priority which must be

given access to health, education and financial resources in order to

improve the opportunities offered to the neediest, thus putting a stop

to the reproduction of inequality. For these measures to be effective, it

is preferable for the countries to have achieved (or begun) their

demographic transitions. We must nevertheless be vigilant, as the

impact of these recommendations will vary according to the countriesstudied.

References

Arellano, M., Bond, S.R., 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carloevidence and an application to employmentequations.Review of Economic Studies58, 277–297.

Azariadis, C., Stachurski, J., 2004. Poverty traps. In: Aghion, P., Durlauf, S. (Eds.),Handbook of Economic Growth. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Blundell, R., Bond, S.R., 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamicpanel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87 (1), 115–143.

Bond, S.R., 2002. Dynamic panel data models: a guide to micro data methods andpractice. Portuguese Economic Journal 1, 141–162.

Bourguignon,F., Ferreira, F.H.G., Walton, M., 2007. Equity, ef ficientand inequality traps:a research agenda. Journal of Economic Inequality 5 (2), 235–256.

Cling, J.P., Cogneau, D., Loup, J., Naudet, J.D., Razafindrakoto, M. and F. Roubaud, 2005, Ledéveloppement, une questionde chances:A propos du rapport surle développement

dans le monde 2006 Equité et Développement, Working Paper DIAL, No. DT/2005(15).

Deaton, A., 2003. Health, inequality, and economic development. Journal of EconomicLiterature 41, 113–158.

Deininger,K., Squire, L.,1996.A newdata setmeasuring incomeinequality.WorldBankEconomic Review 10, 565–591.

Ferreira, F.H.G., Walton, M., 2005. The inequality trap: why equity must be central todevelopment policy. Finance & Development 42 (4), 34–38.

Freedom House, 2005. The Freedom in the World survey, Washington, DC.Galbraith, J.K., Kum, H., 2003. Inequality and economic growth. A global view based on

measures of pay. CESifo Economic Studies 49 (4), 527–556.International Monetary Fond, 2007. International Financial Statistics, Washington, DC.Lynch, J., Smith, G.D., Harper, S., Hillemeier, M., Ross, N., Kaplan, G.A, Wolfson, M., 2004.

Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part 1, a systematicreview. Milbank Quarterly 82 (1), 5–99.

Rao, V., 2006. On ‘inequality traps’ and development policy. World Bank: DevelopmentOutreach, February, 10–13.

Sarkar, J., 2005. Mortality, fertility and persistent income inequality. 75th Southern

Economic Association Conference, Washington D.C.World Bank, 2005. World Development Report 2006: Equity and Development,Washington, DC.

World Bank, 2007. World Development Indicators (WB-WDI), Washington, DC.

7 No collinearity bias exists between these variables.8 In the case of within regressions, the introduction of the dummy variable to

distinguish the countries' profile is not desirable as the countries' specificity has

already been taken into account by the introduction of fixed effects.9 The variables gender and literacyyoung are not studied jointly because of a

redundancy of information which could lead to a collinearity bias in the analyses.10 We have used population growth as a proxy for demographic transition, for there

is no unanimously recognised indicator and there is the problem of the infrequency of

samples for creating them.

3C. Daymon, C. Gimet / Economics Letters xxx (2009) xxx– xxx

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Please cite this article as: Daymon, C., Gimet, C., An empirical test of the inequality trap concept, Economics Letter (2009), doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2009.07.006