Daniel Potash | Master of Architecture Thesis

-

Upload

daniel-potash -

Category

Documents

-

view

229 -

download

4

description

Transcript of Daniel Potash | Master of Architecture Thesis

Daniel S. Potash, Assoc. AIA

MArch 1 | 2014Ball State UniversityCollege of Architecture and Planning

Daniel S

. Potash

RE

OR

GA

NIZ

ING

MU

SE

UM

AR

CH

ITEC

TUR

E: d

esigning a museum

for the indianap

olis motor sp

eedw

ay2014

REORGANIZING MUSEUM ARCHITECTURE:designing a museum for the indianapolis motor speedway

REORGANIZING MUSEUM ARCHITECTURE: designing a museum for the indianapolis motor speedway

Copyright © 2014

Daniel S. PotashCollege of Architecture and PlanningBall State University. Muncie, Indiana

All rights reserved by the author, who is solely responsible for their content, the College of Architecture and Planning, and Ball State University.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission of the copyright owner, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical article and review or where prior rights are preserved.

Potash, Daniel, EditorReorganizing Museum Architecture: designing a museum for the indianapolis motor speedway

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Hall of Fame Museum | iii

Daniel S. Potash

Daniel Potash graduated in 2014 with his MArch degree from Ball State University. Daniel also received his B.S. in Architecture in 2012 from Ball State University’s College of Architecture and Planning where he graduated with honors. Daniel is the recipient of the 2014 Alpha Rho Chi Medal for leadership, service and merit from Ball State University. He has also been award the Best and Brightest of 2012 from the Department of Architecture at Ball State University. Born and raised in Carmel, Indiana, Daniel’s interest in architecture began at a young age. Multiple design classes throughout his high school career ignited his passion for design. Daniel has an interest in technology and is excited to see how these advances can infl uence design and the design process. Daniel will begin his professional career as a Graduate Architect in Indianapolis, Indiana in the summer of 2014.

Hall of Fame Museum | v

AcknowledgmentsI would like to thank the following people, who without their time and guidance this project would not be possible:

Ellen Bireley // Director IMS Hall of Fame MuseumEllen has been a guiding force throughout the project. From the beginning she provided ideas and insight into the current museum and what needs changed. I thank her for taking time out of her busy schedule to sit down with me to discuss my project and the ideas behind it.

Hall of Fame Museum | viiHall of Fame Museum | vii

0107112539456173

Thesis Advisors

Abstract

Precedent Studies

Literature Review

The Project - Preliminary Analysis

The Project - Design Models

The Project - Form Finding and Making

Contents

Site Analysis

The Project - Final Design

Appendix85103

Hall of Fame Museum | 1

Thesis Advisors

Hall of Fame Museum | 3

Andrew WitMajor Advisor // International Practitioner in ResidenceAndrew John Wit is currently the international practitioner in residence at Ball State University. He was selected as one of the incoming “design innovation fellows” for the 2012-2013 academic year. Andrew received his Masters in Architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and his BS in Architecture from the University of Texas at San Antonio. With his previous teaching and practicing in Tokyo, Japan, his work bridges the realms of architecture, urbanism, technology, and infrastructural design. By breaking through the boundaries of architecture and urbanism, Andrew’s works strive for the creation of new architectural and technological typology.

Andrew has spent time at the offi ces of Atelier Bow-Wow, Toyo Ito and associates, as well as holding the position of Senior Design Associate at Tsushima Design Studio in Tokyo, and has spent time practicing, teaching,

and researching in the U.S., Taiwan, Japan, as well as mainland China. His collaborative works have been highly published and have won several awards including the AIA Best of Practice award in 2007, as well as the IFAI Outstanding Achievement Award in 2007.

Hall of Fame Museum | 5

James KerestesMinor Advisor // Design Innovation FellowJames F. Kerestes [RA, LEED AP BD+C] is the founder and principal of blok+WERK studio, an interdisciplinary research lab in the fi eld of architecture and design.

James has a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Syracuse University and a Master of Science in Architecture degree from Pratt Institute. He has taught digital media and emergent technologies at Pratt Institute, Princeton University, and the University of Pennsylvania. For the 2013/2014 Academic year, James has been selected as the Design Innovation Fellow at the College of Architecture and Planning at Ball State University.

In addition to academia, James is a registered architect in the state of Pennsylvania and has been working professionally in Philadelphia area since 2003.

Hall of Fame Museum | 7

Abstract

Hall of Fame Museum | 9

Home to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, Indiana is known worldwide as the racing capital of the world. Over 100 years ago, Indiana had over 150 automobile manufacturers including Duesenberg, Packard, and Studebaker. The famed oval has historically been a proving ground for the consumer automotive industry. The oval was fi rst constructed to be a test track for the local manufacturers, as the road conditions were unacceptable.

Housed within the confi nes of the Speedway is the current Hall of Fame Museum. The museum showcases all of the Indy 500 winner’s cars and allows visitors to see how racing technology has evolved over time. However, the museum fails to embody the spirit of the track. More so, it is currently suffering the fate of many modern museums; a lack of display space as the collection continues to grow. The Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum, similarly to many other museums, currently displays their artifacts in a linear timeline fashion. The drawback to this method is simple; what do you do once you run out of space but the

timeline continues to move forward? How do you allow visitors to continue to enjoy the newest portion of the collection without simply building an addition? Is there a new way of thinking about how to organize the content of a museum and can the architecture also evolve with this new way of thinking?

I propose a project where all these questions can be answered. As the ever-continuing timeline moves forward so can the organization of the artifacts. In close examination to this timeline, many connections and links can be seen throughout history. These connections not only link aspects throughout the timeline, but they begin to speak to how artifacts can be organized, displayed, and experienced. In my proposal, the spaces in the museum begin to allow for these connections. With this new organizational technique, the museum can change and evolve just as the timeline does. The new museum is not only a museum of history; it is a museum for the future. The future of racing. The future of Indiana.

Hall of Fame Museum | 11

Site Analysis

12 | Hall of Fame Museum

Figure 5-1 The Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the Hall of Fame

museum are located West of Indianapolis within the I-465 loop.

Hall of Fame Museum | 13

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway was constructed in 1909 and was originally designed as a testing facility for the local automobile manufacturers. Carl Fisher, an entrepreneur at the time, saw a need for the rapidly growing automobile industry around central Indiana.

“Indiana roads were generally not yet developed, and automotive technology had increased so rapidly that many passenger vehicles had become capable of greater speeds than any dirt road would permit” (“Ownership,” 2013).

Fisher joined with local businessmen James Allison, Arthur Newby and Frank Wheeler. Together, all 4 men began to search for available land outside of Indianapolis. After a ride about 5 miles northwest of the city, they found four 80-acre tracts of land available for sale. Within a short time the land was purchased and the process began to construct the new test track.

A civil engineer from New York, P.T. Andrews, was brought to it to look at the proposed design. “Andrews suggested an outer track of 2.5 miles would fit perfectly. The road course section was abandoned soon after grading began

at the site in march 1909, leaving the 2.5 miles that became the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, The Greatest Race Course In The World” (“Ownership,” 2013).

The first race to occur at the newly created track was actually not with automobiles, but instead with hot air balloons, see Figure 5-4 for an example.

The track was purchased in 1927 by American World War I flying ace Captain Eddie Rickenbacker. Rickenbacker was a regular participant in the balloon race the track had become famous for. Due to America’s involvement in World War II, the track closed and fell into disrepair between 1942 and 1945.

The Indianapolis Motor Speedwaythe racing capital of the world

Figure 5-2 First owner and track builder Carl Fisher, shown here in 1909 when the track first

opened. (“Carl G. Fisher,” Carl G. Fisher)

14 | Hall of Fame Museum

Tony Hulman purchased the track from World War I American flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker after World War II ended.

To this day, the track remains under Hulman family control, with the current chairman being Mari Hulman George. Being the daughter of Tony Hulman, she grew up with racing being a constant part of her life. Her three daughters also currently serve on the Speedway board, continuing the family legacy.

As a part of the Hulman families vision for the track, many different racing events have been added to the growing list of races. NASCAR was first introduced in 1994, and the Brickyard 400 is now one of the largest events in the NASCAR series. From 2000-2007, Formula One returned to America. While it was only for a few years, the United States Grand Prix allowed Americans to experience a different type of open wheel racing. From 2008-2009, MotoGP made an appearance in the famed oval. Many found this a fitting return, as the first motorized race in the track was with motorcycles in 1909.

Looking to what is coming next, the Hulman family is planning for the future of racing. With the city of Speedway proposing and starting a re-development initiative, the entire city is preparing for the future and what it can bring. Discussions and plans are in place for a renovation or an addition to the current Hall of Fame Museum. The current staff is excited and eager to learn and hear ideas for a future museum design.

Figure 5-3 A 1909 advertisement attracting attention to the new testing and racing track. (Otis, Indianapolis motor speedway, greatest race course in the world)

Figure 5-4 Tony Hulman and Karl Kizer ride in a 1909 Stoddard-Dayton

car with hot air balloon in the background. (Satterlee, Tony hulman and karl kizer in stodard-dayton car)

Hall of Fame Museum | 15

16 | Hall of Fame Museum

The Bombardier Pagoda

The Bombardier Pagoda is arguably one of the most recognizable structures within the grounds of the Speedway. The current Pagoda started construction in 1998 and was designed by Browning Day Mullins Dierdorf Architects in Indianapolis, Indiana. “It has nine tiers or viewing levels and reaches a height of 153 feet, equal to a 13-story building” (“Pagoda,” 2013).

The Pagoda is not only used for viewing the track, but actually houses race control facilities, safety, timing and scoring, and radio broadcast booths. As seen in Figure 5-5, the structure has taken on many different forms throughout the life of the track. Carl Fisher, the original builder of the track, had the fi rst Pagoda built in 1913. The day after the race in 1925, it burnt to the ground

(“Pagoda,” 2013). A replacement structure was erected shortly after that stood until the second half of the 20th century.

When Tony Hulman purchased the track after World War II, he began to modernize both the track and all facilities within its grounds. It was at this time that a steel and glass tower was constructed. This version of the Pagoda stood until 1998 when the present structure was constructed.

The Pagoda is built directly on the start and fi nish line. A portion of the famed brick travels under the structure and re-emerges on the back side in the Pagoda Plaza. “Behind the new Pagoda tower is the Pagoda Plaza area,

a focal point for spectators who wish to take a break from viewing the on-track action. The Pagoda Plaza is fully landscaped with grass and a brick walkway shaped like the oval. The area is an ideal location for spectators and families to relax” (“Pagoda,” 2013).

Figure 5-5 Since the opening of the track, the famed pagoda has taken on many different forms. (“Pagoda,” 2013) Figure 5-6

The current Bombardier Pagoda was constructed in 1998 . It was designed by Browning Day Mullins

Dierdorf Architects in Indianapolis, IN.

17

Figure 5-7 The Hall of Fame Museum’s main entrance.

20

The Hall of Fame Museuma museum devoted to automobiles and auto racing

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame Museum is located within the grounds of the track. The first museum was constructed in 1956 by the late Tony Hulman. At the time, the original facility was only large enough to display a few of their historic race cars.

In 1975, Hulman decided to build a much larger facility to house the growing collection of race cars and other racing memorabilia. The new facility houses about 75 vehicles that are on display at all times.

“Constructed of pre-cast cement and Wyoming quartz, the facility encompasses 96,000 square feet of museum and administrative office space. Museum display space measures approximately 30,000 square feet. A glass canopy above the main display floor provides year-round natural light” (“Hall of fame,” 2013).

In addition to housing the race cars from the past races, the museum showcases many other automotive related artifacts. The facility owns more than

Figure 5-8 Inside the current museum’s West wing.

400 different cars that are a part of the Hulman family’s private collection. As seen in Figure 5-8, the collection includes many cars that represent Indiana’s rich history in the automobile industry. The famed Borg-Warner is also showcased as visitors enter in the museum’s doors (“Hall of fame,” 2013).

As the name states, the facility also showcases the racing hall of fame. The current design incorporates

photos or drawings of all living members along with

inscriptions of all the members that have passed.

While the museum has an annual visitor amount of about 200,000, most of the attendance happens during the month of May coinciding with the race season. Many different educational curriculum incorporate the museum into their teaching. Student groups are a common occurrence within the museum. The facility occasional caters to private parties, but a majority of the attendance occurs from daily visitors.

21

Figure 5-9 Inside the current museum’s East wing.

22 | Hall of Fame Museum

Ellen Bireley is the current Director of the IMS Hall of Fame Museum. During an interview, she spoke of the normal attendance schedule the museum receives. “We average about 200,000 visitors a year. About one third of that attendance occurs during the month of May while another majority is in June and August when schools are on break” (Bireley, 2013).

Due to the fact that the museum was built in the 70’s, and with the growing collection of cars, the facility is literally running out of space. “When I walk through the exhibit, I feel like I am in a parking lot,” Bireley speaks about how she feels of the current facility (Bireley, 2013). The museum actually owns more than 400 cars but only has the capability to display roughly 75 at one time.

Moving the cars is also an issue within the current facility. The majority of the collection is stored in the basement. With the only access being a loading dock and a door at the far corner of the first floor, moving cars can only occur during optimal weather conditions. “We either have to wait for it to be nice enough or load the cars in a trailer for the trip around the building. It is a real pain” (Bireley, 2013). That being said, the current facility rotates cars about every 6 months with large rotations happening every one to one and a half years.

“Our cars are very sensitive to sunlight. If you move one of the leather straps holding an engine cover on, you will see just how much the paint has faded,” Bireley mentions (Bireley, 2013). It is important to note that the current museum does feature a large skylight that divides the East and West wings.

Ellen is interested in getting the public more involved in the other facets of the museum, “Many museums are now allowing visitors to experience a full restoration process. We do restorations in our facility, but no visitors get to see them” (Bireley, 2013). Besides allowing visitors to experience a restoration she wants them to experience the race cars in new ways.

The museum is exploring ideas to build additions to their current facility to allow some of these ideas to come to fruition. LEED is an important consideration that will take place throughout this process. The speedway itself is having a solar farm installed close to turn 3 in the near future. As the future becomes the present, the Hall of Fame Museum is ready to move into what is to come.

Discussing The Current Museuman interview with ellen bireley

Figure 5-10 The Speedway and the current museum are both listed on the National Register of Historic places.

Hall of Fame Museum | 25

Precedent Studies

Figure 6-1 The Porsche Museum designed by Delugan Meissl

Associated Architects in Germany. (“Porsche museum,” 2013)

Hall of Fame Museum | 27

Porsche MuseumDelugan Meissl Associated ArchitectsStuttgard-Zuffenhausen, Germany

The Porsche Museum in Germany is a facility designed not only to showcase the history of the brand, but to showcase the brand itself. The designers set out to design a building that “reflects the authenticity of Porsche products and services as well as the company’s character, while also reshaping Porscheplatz with an unmistakable appearance,” (“Porsche museum,” 2013).

At first glance the exhibition space seems to be detached from the folded topography below; this was in fact a goal of the designers. They wanted to open the space between the streetscape and the exhibition. This was achieved by not only separating the two areas, but also by placing reflective material on the underside to allow more light to enter the created spaces.

“Here, speed and passion find their spatial equivalents and can be impressively retraced in the sensual experience. Experience and the opportunity to experience were the primary design parameters through respective spatial allocations in the basic architectural concept,” (“Porsche museum,” 2013).

The entire design is based no only on the cars housed within, but is also based on the experience the cars give to their users. This experience is reflected within the design and was an important aspect from the very beginning of the design process.

Figure 6-2 The Porsche Museum was designed by Delugan Meissl Associated Architects in Germany. (“Porsche museum,” 2013)

Figure 6-3 Here, the stainless steel track can be seen that defines

the thematic islands. (“Porsche museum,” 2013)

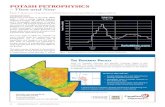

The architect of the Porsche Museum developed a concept of thematic islands to display the automobiles. “The presentation area of each island is defined by stainless steel tracks which are mounted flush into the floor and which are used for the fixing of such exhibition elements as panels of text, screens and floor markings,” (Merz, 2010). A simple diagram can be seen in Figure 6-4 on page 29.

Not only does this system allow for visitors to quickly and easily understand where the exhibits are located, it also allows for quick changes to the vehicles on display. When an exhibit is changed, all the appropriate signage can be swapped out as easily as the vehicles themselves. The stainless steel tracks pull reference to

the starting grid race cars use at the beginning of each race.

Due to the fact that these island are located on floor level, visitors are welcome to experience the car from all angles. While this does open opportunity for new experience, visitors can easily distinguish where exhibit begins and walkway ends.

These thematic island are often associated with other methods of display information. Most are associated in a “triad” which is discussed in the next section.

Thematic Islands

Figure 6-4 A diagrammatic explanation of the thematic island approach to displaying the cars.(Merz, 2010)

The Display Triad

Each thematic island is not only an individual island of learning, it is an island associated with a triad of information. These triads “offer the visitor various levels of information and details, tailored to their level of prior knowledge and intersect. The visitor who knows little of the subject is offered an insight into a wealth of fascinating exhibits and stories in which the expert visitor will also find a rich seam of more complex information and previously unknown connections,” (Merz, 2010).

As the visitors travel along the product history wall, they approach a reference exhibit. As seen in Figure 6-6 on page 31, this example uses the exhibit of lightness. The reference exhibit showcases a few cars that begin to speak of the design concept of lightness.

The visitor then approaches a display case which again showcases the concept previously introduced in the reference cars. Directly after the display case is a speaking image, which showcases further the idea first introduced in the reference with unique display elements. As a visitor looks behind them, a thematic island demonstrates all the ideas previously discussed in the triad.

The entire museum is composed of this concept to easily guide guests through its exhibits.

Figure 6-5 Modern cars are displayed in a “break-away” fashion

to better describe the automotive technologies. (“Porsche museum,” 2013)

Figure 6-6 Here, it can be seen how the visitor experiences an exhibit utilizing the triad method.(Merz, 2010)

Figure 6-7Here the entire display triad can be seen in the

museum.(“Porsche museum,” 2013)

34

Figure 6-8 The BMW Welt designed by Coop Himmelb(l)au in Munich,

Germany. (“Bmw welt,” 2013)

Hall of Fame Museum | 35

Since its construction in 2007, the BMW Welt has been considered to be the heart of the German automaker. The BMW Welt, or BMW World in English, serves as “the delivery center for new BMW automobiles and a brand experience rolled into one” (“Bmw welt,” 2013). The building is not only home to the BMW Group but also serves as the home to its four brands: BMW, MINI, Rolls Royce Motor Cars, and Husqvarna Motorcycles.

“The Junior Campus at BMW Welt gives young visitors an introduction to the world of mobility and is a place they can explore with zeal,” (“Bmw welt,” 2013). The facility prides itself on giving young people a place to not only learn about BMW automobiles, but a place to learn about the art of design. “The design is characterized by high-quality materials, clear shapes and brightly shining colours typical of BMW. It provides the perfect setting in which to showcase technologies, engine construction, the design process and the current BMW models” (“Bmw welt,” 2013).

BMW WeltCoop Himmelb(l)au, architectMunich, Germany

Figure 6-9The BMW Welt concept designed by Coop Himmelb(l)au in Munich, Germany.(“Bmw welt,” 2013)

36

Figure 6-10 Multiple levels allow visitors to experience the automobiles from

unique and altering angles. (“Bmw welt,” 2013)

The Educational Concept

A key concept of the BMW Welt is integrating education into a young guest’s experience. Young children are given insight into “mobility, sustainability, safety, the environment, vehicle technology and design” (“Bmw junior program,” 2013).

Children are given the opportunity to receive the education through multiple available workshops. These workshops are divided into ago appropriate subject matter that is closely linked to current school curricula (“Bmw junior program,” 2013). These workshops are closely linked to age-specific museum tours.

The available workshops allow children to learn and explore what makes a car move. They can also learn about recycling and designing with sustainablity in mind. There is even a workshop that utilizes photography to demonstrate the history of automobile construction and technology (“Bmw junior program,” 2013).

37

Figure 6-11 The cars are displayed on raised pedestals that allow invite visitors to step up and experience the designs. (“Bmw welt,” 2013)

Energy Efficiency

At first glance visitors may not notice the amount of sustainable technology located on and within the BMW Welt, but it is actually a technological innovation. The now iconic Double Cone helps to provide some of the main structural support for the “cloud roof”.

This cloud roof is home to “an impressive flat roof-integrated PV system made up of 3,660 solar modules,” (Kriscenski, 2007). This system alone can deliver a minimum of 824kWp (kilowatt-peak). With this system installed, it is estimated that it can reduce the energy demands by about 30%.

“A major goal in designing the systems was to save energy. This aim is achieved by minimizing the mechanical apparatus for ventilation, heating and cooling,” (“Bmw welt /,” 2009). This concept is proven in the main Hall space, where it is naturally ventilated and does not follow standard logic of heating and ventilation. “A natural air supply is generated by thermal currents, wind pressure and turbulences...Air intake and outflow take place through automatically controlled vents” (“Bmw welt /,” 2009).

Hall of Fame Museum | 39

Literature Review

Hall of Fame Museum | 41

This article studies the connection between the museum and the education field. The authors begin by discussing the disconnect between what the current education systems want to achieve and how they actually go about achieving it.

“Current education systems tend to anchor learning in formal environments, mostly in classrooms and with textbooks,” (Vartiainen & Enkenberg, 2013). They go on to mention “while the overall goal of schooling is to prepare young people to be able to participate responsibly and productively in society, the actual practices through which schooling takes place contradict with the practices that exist beyond the school walls,” (Vartiainen & Enkenberg, 2013).

This learning, the authors believe, most often occurs at museums and science centers. They believe this is due to the fact that the facilities provide a physical environment that is not usual in daily life (Vartiainen & Enkenberg, 2013). However, they discuss that even with advances in

technology and museum design, the museum visit itself has not changed. This is due to the fact that many visits are not planned ahead and little preparation is made. “Consequently, a typical museum visit is organized as a structured, docent-directed, and lecture-oriented tour,” (Vartiainen & Enkenberg, 2013).

Their research has found that there is a pressing need “to provide teachers and museum staff with viable alternatives to their current ways of conducting school excursions, and to apply more student-centered approaches that allow active learning,” (Vartiainen & Enkenberg, 2013).

What can be taken away from this article is the importance of how students interact with the museum. This can bet taken as how they interact with the exhibits but also how they interact with the museum itself. It is possible that the facility needs to adapt to the variety of visitors.

Learning from and with museum objects:design perspectives, environment, and emerging learning systemsHenriikka Vartiainen | Jorma Enkenberg

Hall of Fame Museum | 43

This book is a go-to guide of information for architects regarding museum design. It is part of a series of books that gives essential information that is designed to be used throughout the design process (Rosenblatt, 2001).

While this book is broken into specific museum typologies, general information can be taken from each section and later applied to better create a holistic design. A very common theme amongst the art museums is to utilize natural lighting while balancing the light to not disrupt the delicate works (Rosenblatt, 2001). This careful balance is often achieved by the use of special films/substrate installations or sensor regulated louvers.

While most of the art facilities are larger, they all seem to utilize specific wayfinding techniques. Some of these include a new trend of automated sound tracks with headphones. All art museums also seem to feature some sort of cafe or food service facility (Rosenblatt, 2001).

Design factors can also be taken from the history museum

typology. Due to the nature of learning history, many of these museums feature education and classroom facilities. They also feature many cinemas and viewing rooms to show historical documentation.

One of the most interesting typologies is the science and natural history museums. With science and technology being a very fast changing field, these facilities need “to anticipate and integrate fast-changing scientific discoveries into the new center,” (Rosenblatt, 2001). Multimedia also tends to play a crucial role in this type of museum.

This book also incorporates a technical note chapter with important information that must be analyzed during the design process. These aspects include notes on: lighting, entrances, galleries, illumination levels, lamp types, MEP information, security, and fire protection. The information presented here will be closely looked at in the design of this project.

Building Type Basics for MuseumsArthur Rosenblatt

Hall of Fame Museum | 45

The Project Preliminary Analysis

46 | Hall of Fame Museum

Figure 8-1 Graphic representation of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

The oval course, road course, and pit areas can be seen.

Hall of Fame Museum | 47

One of the first steps in the design process was to try to understand more about the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and what happens at the track during a race. This type of research is necessary for a designer to properly understand what and who they are designing for.

The initial research lead to a series of three different diagrams (Figure 8-2, Figure 8-3, Figure 8-4). These diagrams show both facts and figures about the track and the current Dallara Indycar. Many of the statistics are rooted in history and relate to innovations that have occurred at the track. There were also a number of connections that were found between the Indycar and the consumer automobile.

All of these facts and connections allowed for a design idea to begin to develop. The concept of allowing the connection between the Indycar and the consumer automobile began to form. A closer look into the history of racing and the timeline it has created was deemed necessary.

The Indianapolis Motor Speedwaythe racing capital of the world

33cars

compete

INDIANAPOLIS500

RACE

$1for seats in the

grandstand

80,200spectators

$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$

1911INAUGURAL RACE

TOTAL COSTTO RACE

$996,400

250,000permanent seats

200total laps

2.5MILEoval lap 500TOTAL

MILES

1,025total acres

WORLD’S LARGEST SPECTATOR SPORTING FACILITY

at the first 500

Figure 8-2 Informational diagram regarding the history and

statistics of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

33cars

compete

INDIANAPOLIS500

RACE

$1for seats in the

grandstand

80,200spectators

$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$

1911INAUGURAL RACE

TOTAL COSTTO RACE

$996,400

250,000permanent seats

200total laps

2.5MILEoval lap 500TOTAL

MILES

1,025total acres

WORLD’S LARGEST SPECTATOR SPORTING FACILITY

at the first 500

1911FIRST REAR-VIEW MIRROR

1921four-wheelhydraulicbrakes

1925FRONT-WHEELDRIVE

1991ENERGY

ABSORBINGATTENUATOR1993

crash datarecorder

2002SAFERbarrier

1935first mandatory

helmets

1921four-wheel drive

INDIANAPOLISMOTOR

SPEEDWAY

WORLD’S LARGEST SPECTATOR SPORTING FACILITYFigure 8-3

Informational diagram showing innovations and technology fi rst tested at the Indianapolis Motor

Speedway.

1911FIRST REAR-VIEW MIRROR

1921four-wheelhydraulicbrakes

1925FRONT-WHEELDRIVE

1991ENERGY

ABSORBINGATTENUATOR1993

crash datarecorder

2002SAFERbarrier

1935first mandatory

helmets

1921four-wheel drive

INDIANAPOLISMOTOR

SPEEDWAY

WORLD’S LARGEST SPECTATOR SPORTING FACILITY

DALLARADW12

INDYCARAN ANATOMY OF A DALLARA INDYCAR

FRONT WINGconfigurableaerodynamic

ALUMINUMhoneycombchasis core

FIRESTONE FIREHAWKweight of indycar

series car atspeed is 4x

the staticweight

$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$

TOTAL NEWCAR COST

$385,800

$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$

REAR WINGconfigurable

aerodynamic

ROLL HOOPresists 40%higher loads

MATERIALhoneycombcarbon fiber

BORGWARNERturbochargertitanium and

aluminide turbine

HORSEPOWER550-700

3.5 liter V-8230 mph

Figure 8-4 Informational diagram showing technology and

statistics of the new Dallara DW12 Indycar, fabricated in Speedway, IN.

DALLARADW12

INDYCARAN ANATOMY OF A DALLARA INDYCAR

FRONT WINGconfigurableaerodynamic

ALUMINUMhoneycombchasis core

FIRESTONE FIREHAWKweight of indycar

series car atspeed is 4x

the staticweight

$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$

TOTAL NEWCAR COST

$385,800

$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$

REAR WINGconfigurable

aerodynamic

ROLL HOOPresists 40%higher loads

MATERIALhoneycombcarbon fiber

BORGWARNERturbochargertitanium and

aluminide turbine

HORSEPOWER550-700

3.5 liter V-8230 mph

Figure 8-5 Maps showing the location and size of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in relation to downtown Indianapolis.

The current Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame Museum is located within the confi nes of the track. This location, while it allows a direct connection to the race itself, is problematic in many ways. A person driving by the outside of the track might not even know the museum exists, except for the fact that there is a very small sign. It is also problematic in the fact that there is not much room to grow. As can be seen in Figure 8-6, land inside the track is valuable real estate.

With these ideas in mind, a new location for the museum is proposed on the corner of W. 16th St. and W. Main St. This will allow for much more of a visual presence for the new museum in the city of Speedway. It also allows for a direct connection to the Dallara Indycar Factory, which is located directly South of the new location. The proposed location can also be seen in Figure 8-6.

The Indianapolis Motor Speedwayunderstanding the site and the current museum location

Figure 8-6 An aerial shot showing the location of the

current Hall of Fame Museum inside the and the proposed new location outside.

The Evolution of the Indy Carthrough safety and performancefrom 1911 to 2014

19111966

19391925

19531991

19792014

1911�rst rear view mirror

1989hans device designed

2000hans device smallerdue to 2 deaths

hans device requireddue to another death

2001

1965goodyear tire testing to prevent blowouts

2000�restone sole tire supplier

astronaut pete conradhelped develop nylon based �re suit

1967

�reball roberts death due to �re after crash

1964

1940utilize cork in helmet lining

carbon �ber body research and usage begins

2004

1993extensive helmetwind tunnel tests

1935�rst mandatory helmets

front wheel drive utilized on race car

1925

2012new dallara indycarintroduced

duesenberg utilized four wheel hydraulic brakes on race cars

1914

modernized aerodynamicsteardrop-shaped tails

1922

1993�rst use of crashdata recorders

1930mandate to return to production based cars

1980direct-shift gearbox (dsg) testing andimplementation1928

dual overhead camengine production

1921passenger cars utilize hydraulic brakes

1921four wheel drive utilized on race car

2002

helmet mandated to feature “hats-o� bladder”

2003

Figure 8-7 A brief timeline highlighting events that have occurred throughout the history of racing.

Hall of Fame Museum | 57

The Evolution of the Indy Carthrough safety and performancefrom 1911 to 2014

19111966

19391925

19531991

19792014

1911�rst rear view mirror

1989hans device designed

2000hans device smallerdue to 2 deaths

hans device requireddue to another death

2001

1965goodyear tire testing to prevent blowouts

2000�restone sole tire supplier

astronaut pete conradhelped develop nylon based �re suit

1967

�reball roberts death due to �re after crash

1964

1940utilize cork in helmet lining

carbon �ber body research and usage begins

2004

1993extensive helmetwind tunnel tests

1935�rst mandatory helmets

front wheel drive utilized on race car

1925

2012new dallara indycarintroduced

duesenberg utilized four wheel hydraulic brakes on race cars

1914

modernized aerodynamicsteardrop-shaped tails

1922

1993�rst use of crashdata recorders

1930mandate to return to production based cars

1980direct-shift gearbox (dsg) testing andimplementation1928

dual overhead camengine production

1921passenger cars utilize hydraulic brakes

1921four wheel drive utilized on race car

2002

helmet mandated to feature “hats-o� bladder”

2003

As previously mentioned, a close look at the history of racing and the timeline it produced was conducted. This search was actually much more difficult than expected, as no one has actually assembled a single timeline of racing events and technological breakthroughs.

After a thorough search, a small timeline was developed (see Figure 8-7). While this is only a small snapshot of racing events, it begins to tell a very important story. If one looks closely at the events, small connections and links can be made.

These connections became important in allowing an organizational strategy of building content to develop. Instead of organizing the museum collection in a linear timeline fashion, the content can be organized based on the connections found throughout history. This allows for a much more fluid and flexible layout for the museum curators.

The Timeline of Historyfinding and making connections throughout history

The Evolution of the Indy Carthrough safety and performancefrom 1911 to the future

19111966

19391925

19531991

19792002

20142070

20422028

20562098

2084

Figure 8-8 A new proposed museum would need to tackle the issue of the ever-evolving timeline and have to deal with a growing collection.

Hall of Fame Museum | 59

The Evolution of the Indy Carthrough safety and performancefrom 1911 to the future

19111966

19391925

19531991

19792002

20142070

20422028

20562098

20842070

20422028

20562098

2084

The issue that many museums are currently facing is an ever-evolving and continuing timeline. This not only leads to a growing collection, but it also leads to a growing lack of space for display purposes.

As previously mentioned, the organizational strategy of connections throughout history solves this problem. As the timeline continues a simply shift in the displays is necessary. A certain display may grow while another may shrink. Allowing the spaces in the building to refl ect this idea is crucial as the content is shifted around the building.

The Ever-Evolving Timelinehow to deal with a growing collection

Hall of Fame Museum | 61

The Project Design Models

202625521213274981122197910148316776087821156551863419181

PC

Race: Indianapolis 500Year: 2013Lap: 1 of 200Lap Status: G

Out Of Race

Figure 9-1 A simple track diagram was developed with

dots to represent each of the drivers in the race.

Hall of Fame Museum | 63

Since a new museum would be focused around the idea of a race and what happens during one, it was a crucial step to thoroughly analyze and examine what happens during a race.

This analysis was conducted by looking very closely at the 2013 Indianapolis 500 race. A video was paused every five minutes to see what was happening and where each of the drivers were currently located on track. This analysis lead to many trends and consistencies.

One of the most interesting trends was watching where the cars were located coming in and out of the turns, which can be considered the most dynamic part of the race. While most drivers would follow the same path, there would occasionally be an outlier that would lead their own way. This often times either lead to success in a pass, or failure in terms of a crash.

It was also interesting listening to the commentary during the race. The announcers stated many facts that would not even be though of. While it seems that a driver would want to lead for as much of the race as possible, this is actually highly undesirable. When a car is leading the

race, they are cutting through the air much more than another car behind them. This not only leads to a slower top speed, but also to much more fuel being burned. There is an art and science to racing that the average person doesn’t see while watching from the stands.

The 2013 Indianapolis 500analyzing an indianapolis 500 race to find trends

20

26

25

5

2

12

1

3

27

4

98

11

22

19

7

9

10

14

83

77

8

21

6

55

18

41

91

81

Race: Indianapolis 500Year: 2013Lap: 200 of 200Lap Status: Y/W

PC

Out Of Race

16

15

78

63

60

20

26

25

5

2

12

1

3

27

98

11

22

19

7

9

10

14

83

16

77

608

78

21

15

6

55

18

63

41

91

81

Race: Indianapolis 500Year: 2013Lap: 14 of 200Lap Status: G

PC

4Out Of Race

Figure 9-2 A series of diagrams showing driver positions

throughout the 2013 Indianapolis 500 race.

20

26

25

5

2

12

13

27

98

11

22

19

7

9

10

14

83

77

60

8

21

55

18

41

91

81

Race: Indianapolis 500Year: 2013Lap: 38 of 200Lap Status: Y

PC

16

15

78

63

4 6Out Of Race

20

26

25

5

2

12

1

3

27

98

11

22

19

7

9

10

14

83

77

60

8

21

55

18

41

81

Race: Indianapolis 500Year: 2013Lap: 65 of 200Lap Status: G

PC

16

15

78

4 6 91Out Of Race

63

20

26

25

5

2

12

1

3

27

98

11

22

19

7

910

14

83

77

8

21

55

18

41

81

Race: Indianapolis 500Year: 2013Lap: 77 of 200Lap Status: G

PC

16

15

78

60

4 6 91Out Of Race

63

20

26

25

5

2

12

1

3

27

4

98

11

22

19

7

9

10

14

83

77

8

21

6

55

18

41

91

81

Race: Indianapolis 500Year: 2013Lap: 200 of 200Lap Status: Y/W

PC

Out Of Race

16

15

78

63

60

Figure 9-3 A series of diagrams showing driver positions

throughout the 2013 Indianapolis 500 race.

Hall of Fame Museum | 67

One of the most important parts of a race is the act of passing another car. Without this action, the race would simply be cars going very fast in a circle for long periods of time. In order to better understand a pass, a close look was taken into the steps necessary to successfully overtake another car.

As can be seen in Figure 9-4, passes typically occur on the straightaway. It can be noted that some passes are attempted during a turn but typically result in a failure leading to a crash. The straightaway pass can be much more successful in the fact that the drivers utilize the car’s “boost” abilities to a fuller extent.

The Art of Passinganalyzing an indycar during a pass

Figure 9-4 A diagram showing how an indycar passes and the path it has to follow.

68 | Hall of Fame Museum

Track Operationsa design model

Straight Compression - Release - Compression Expansion - Compression - Expansion Degree of Intensity

Track Operationsa design model

Straight Compression - Release - Compression Expansion - Compression - Expansion Degree of Intensity

Figure 9-5 After the analysis of a pass occurred, four different

conditions were found in the interstitial space between cars.

Hall of Fame Museum | 69

During the analysis of a pass, many interesting conditions occurred in the interstitial space between the cars. Not only was there an overall conditions created (see Figure 9-4), but smaller conditions were also generated. These small conditions were generalized into four different diagrams (see Figure 9-5).

These four conditions became a set of macro design models to be later utilized in the overall design and organization of the building. Some examples could be allowing a visitor to feel the act of compression and release through different sized adjacent spaces. These conditions can be directly linked back to the connections made in the timeline. Each connection, or display space, can have a different feeling associated with the experience (size, shape, quality of the space).

The Macro Design Modela look at the interstitial space created during an indycar pass

The Evolution of the Indy Carthrough safety and performancefrom 1911 to 2014

19111966

19391925

19531991

19792014

1911�rst rear view mirror

1989hans device designed

2000hans device smallerdue to 2 deaths

hans device requireddue to another death

2001

1965goodyear tire testing to prevent blowouts

2000�restone sole tire supplier

astronaut pete conradhelped develop nylon based �re suit

1967

�reball roberts death due to �re after crash

1964

1940utilize cork in helmet lining

carbon �ber body research and usage begins

2004

1993extensive helmetwind tunnel tests

1935�rst mandatory helmets

front wheel drive utilized on race car

1925

2012new dallara indycarintroduced

duesenberg utilized four wheel hydraulic brakes on race cars

1914

modernized aerodynamicsteardrop-shaped tails

1922

1993�rst use of crashdata recorders

1930mandate to return to production based cars

1980direct-shift gearbox (dsg) testing andimplementation1928

dual overhead camengine production

1921passenger cars utilize hydraulic brakes

1921four wheel drive utilized on race car

2002

helmet mandated to feature “hats-o� bladder”

2003

The Big Ideaa design model

Figure 9-6 The concept of the timeline was

abstracted into a design model to allow for further design development.

Hall of Fame Museum | 71

With all the ideas in place, it was time to develop an overall building design model. This model would eventually become the basis for how the form and content would be arranged and organized. As previously discussed, the overall form would be based on the idea of the timeline and connections throughout history.

The idea of time and continuing time was summarized in Figure 9-6. Time is an ever evolving and continuing concept, therefore it continues on for infinity. If one looks closely at the timeline of racing history, it can be seen that there are times of more activity than others, so the infinity idea shifts. There are also times of even greater intensity and density, so the idea of infinity begins to fade in and out as it continues.

An even closer look shows that occasionally the timeline veers off course and something new happens. Slowly it returns back into the normal rhythm of time. This ever evolving and changing concept can be seen at the bottom of Figure 9-6. This ultimately became the overall design model for the new proposed museum.

The Overall Design Modelabstracting the timeline to become a building design model

Hall of Fame Museum | 73

The Project Form Finding and Making

Figure 10-1 Study diagrams showing the beginning of the form

fi nding exercise.

Hall of Fame Museum | 75

As previously discussed, the form of the building is a combination of many different factors. Some of the most important factors come from both site conditions and from internal programmatic conditions. A quick site analysis was performed to better understand how the site will affect the building’s final form (see Figure 10-2 and Figure 10-3).

The two main conditions found on the site that would react against the form were pedestrian flow and automobile flow. These different conditions began to push and pull the form to develop a building shape. These forces and their movements can be seen in Figure 10-4.

The ideas and concepts of the timeline and organizing the content based on connections also continued to influence the form as well. Areas that allowed for pedestrian entrance come down and welcome people. While areas that the automobile would drive through need to lift and allow easier access. Interior spaces begin to reflect the macro design models discussed in Figure 9-5, where areas begin to compress and then release visitors.

Finding A Formdeveloping and evolving form from site/programmatic conditions

76 | Hall of Fame Museum

w 16th. streetw 16th. street

w m

ain streetw

main street

crawfordsville road

Figure 10-2 A diagram showing the site analysis during an average

day based on pedestrian and automotive factors.

Hall of Fame Museum | 77

w 16th. streetw 16th. street

w m

ain street

crawfordsville road

w m

ain street

Figure 10-3 A diagram showing the site analysis during the month of May based on pedestrian and automotive factors.

Figure 10-4 A diagram showing the development of the form based on site conditions as previously described.

Figure 10-5 A study of the form development. These renderings begin to show the overall form from all directions.

Figure 10-6 A site perspective shows the proposed museum in relation to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to the North and the Dallara Indycar Factory to the South.

Hall of Fame Museum | 85

The Project Final Design

Figure 11-1 A top view rendering of the fi nal form, which

was developed from site conditions.

Finalizing the form was a matter of tweaking what had already been developed from the studies performed during the form finding exercise. These tweaks were conducted based on changes that occurred on the interior programming and a few other site conditions.

The final form developed is only one iteration of what the building could look like. As more and more constraints are added to the digital model, the form can continue to develop and evolve. This relates directly to the idea of the ever-evolving timeline and how it changes and develops. Additional constraints could be more programmatic conditions, structural conditions, and code complaint ideas.

As mentioned, this iteration of form is only one idea of what it could be. Taking the idea of the timeline and connections throughout history, the form can potentially take any shape for any building type. The important aspects stand strong: allowing a flexible layout where content can be easily rearranged, allowing multiple non-hierarchical points of entrance, and allowing visitors to experience evolving and changing spatial conditions.

The Final Formrefining the form and developing interior spaces

A Look Inside The Museumunderstanding the interior of the proposed museum

It can be seen in Figure 11-2 below that the interior spaces of the proposed museum are very fl owing and allow for a high level of fl exibility in terms of display spaces. Looking back to the macro design models in Figure 9-5, the interior spaces begin to refl ect the concepts found in the passing of an Indycar during a race.

A visitor can be experiencing a portion of the museum when they are faced with the option of a bifurcating path. This type of path occurs when a portion of the timeline branches off and two events begin to occur

simultaneously. There are also portions where the visitor can experience a much more intimate space, possibly a crash in history, then suddenly the space opens to a grand view of a major portion of the museum. These types of moves allow the visitor to experience the artifacts in a much more personal and intimate level.

It can be seen in Figure 11-3 and Figure 11-4 that the spaces in the museum are very fl exible. This allows the curator to re-arrange content as the timeline of racing history continues to evolve and change into the future.

Figure 11-2 A section view shows how the interior space

is divided and experience by the visitors.

Figure 11-3 A section showing one iteration of how the collection can be displayed and organized.

Figure 11-4 A section showing another iteration of how the collection can be

displayed and organized. This refl ects the fl exibility of the spaces.

Figure 11-5 A rendering showing the Main Street side of the new museum.

Figure 11-6 A rendering showing the tailgating side of the new museum.

Figure 11-7 A photograph of the fi nal display boards displayed on the 4th fl oor of the Architecture Building.

Figure 11-8 An up-close view of the fi nal 3D printed form

model.

Figure 11-9 An up-close view of the design iteration models

with the descriptive diagram placed above.

The fi nal display was developed to effectively show and communicate the ideas of the project. Twenty-two separate boards were created to allow readers to easily understand the project. The boards were organized based on the design process and to demonstrate the fl ow of ideas from the beginning to the end.

Physical models of both the fi nal form and of the form iterations were 3D printed. The fi nal model was crafted and polished to represent the same physical form that can be seen in the renderings. It can be seen in Figure 11-9 that the iteration models were displayed directly below the diagram explaining the design decisions. This helps the viewer to experience the design in all dimensions.

The Final Displaycommunicating the project ideas

Figure 11-10 The fi nal presentation being given to a group of visiting jurors on April 28th, 2014.

Hall of Fame Museum | 103

Appendix

Hall of Fame Museum | 105

Figures

Figure 3-1 Andrew Wit, International Practitioner in Residence .............................................................................................. 2

Figure 3-2 James Kerestes, Design Innovation Fellow .......................................................................................................... 4

Figure 5-1 The Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the Hall of Fame museum are located West of Indianapolis within the I-465 loop. ....................................................................................................................................................... 12

Figure 5-2 First owner and track builder Carl Fisher, shown here in 1909 when the track first opened. (“Carl G. Fisher,” Carl G. Fisher) .................................................................................................................... 13

Figure 5-3 A 1909 advertisement attracting attention to the new testing and racing track. (Otis, Indianapolis motor speedway, greatest race course in the world) ......................................................... 14

Figure 5-4 Tony Hulman and Karl Kizer ride in a 1909 Stoddard-Dayton car with hot air balloon in the background. (Satterlee, Tony hulman and karl kizer in stodard-dayton car) ..................................................................... 14

Figure 5-5 Since the opening of the track, the famed pagoda has taken on many different forms. (“Pagoda,” 2013) .......... 16

Figure 5-6 The current Bombardier Pagoda was constructed in 1998 . It was designed by Browning Day Mullins Dierdorf Architects in Indianapolis, IN. ................................................................................................................................ 16

Figure 5-7 The Hall of Fame Museum’s main entrance. ........................................................................................................ 19

Figure 5-8 Inside the current museum’s West wing. ........................................................................................................ 20

106 | Hall of Fame Museum

Figure 5-9 Inside the current museum’s East wing. ........................................................................................................ 21

Figure 5-10 The Speedway and the current museum are both listed on the National Register of Historic places. .......... 23

Figure 6-2 The Porsche Museum was designed by Delugan Meissl Associated Architects in Germany. (“Porsche museum,” 2013) ................................................................................................................................ 27

Figure 6-3 Here, the stainless steel track can be seen that defines the thematic islands. (“Porsche museum,” 2013) ................................................................................................................................ 28

Figure 6-4 A diagrammatic explanation of the thematic island approach to displaying the cars. (Merz, 2010) ....................................................................................................................................................... 29

Figure 6-5 Modern cars are displayed in a “break-away” fashion to better describe the automotive technologies. (“Porsche museum,” 2013) ................................................................................................................................ 30

Figure 6-6 Here, it can be seen how the visitor experiences an exhibit utilizing the triad method. (Merz, 2010) ....................................................................................................................................................... 31

Figure 6-7 Here the entire display triad can be seen in the museum. (“Porsche museum,” 2013) ................................................................................................................................ 33

Figure 6-8 The BMW Welt designed by Coop Himmelb(l)au in Munich, Germany. (“Bmw welt,” 2013) ........................................................................................................................................... 34

Figure 6-9 The BMW Welt concept designed by Coop Himmelb(l)au in Munich, Germany. (“Bmw welt,” 2013) ........................................................................................................................................... 35

Hall of Fame Museum | 107

Figure 6-10 Multiple levels allow visitors to experience the automobiles from unique and altering angles. (“Bmw welt,” 2013) ........................................................................................................................................... 36

Figure 6-11 The cars are displayed on raised pedestals that allow invite visitors to step up and experience the designs. (“Bmw welt,” 2013) ........................................................................................................................................... 37

Figure 8-1 Graphic representation of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The oval course, road course, and pit areas can be seen. ................................................................................................................................................................... 46

Figure 8-2 Informational diagram regarding the history and statistics of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. ...................... 48

Figure 8-3 Informational diagram showing innovations and technology first tested at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. ............................................................................................................................................................................... 50

Figure 8-4 Informational diagram showing technology and statistics of the new Dallara DW12 Indycar, fabricated in Speedway, IN. ....................................................................................................................................................... 52

Figure 8-5 Maps showing the location and size of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in relation to downtown Indianapolis. ............................................................................................................................................................................... 54

Figure 8-6 An aerial shot showing the location of the current Hall of Fame Museum inside the and the proposed new location outside. ........................................................................................................................................... 55

Figure 8-7 A brief timeline highlighting events that have occurred throughout the history of racing. ................................. 56

Figure 8-8 A new proposed museum would need to tackle the issue of the ever-evolving timeline and have to deal with a growing collection. ........................................................................................................................................... 58

108 | Hall of Fame Museum

Figure 9-1 A simple track diagram was developed with dots to represent each of the drivers in the race. ...................... 62

Figure 9-2 A series of diagrams showing driver positions throughout the 2013 Indianapolis 500 race. ...................... 64

Figure 9-3 A series of diagrams showing driver positions throughout the 2013 Indianapolis 500 race. ...................... 66

Figure 9-4 A diagram showing how an indycar passes and the path it has to follow. ......................................................... 67

Figure 9-5 After the analysis of a pass occurred, four different conditions were found in the interstitial space between cars. ............................................................................................................................................................................... 68

Figure 9-6 The concept of the timeline was abstracted into a design model to allow for further design development. ............................................................................................................................................................................... 70

Figure 10-1 Study diagrams showing the beginning of the form finding exercise. ......................................................... 74

Figure 10-2 A diagram showing the site analysis during an average day based on pedestrian and automotive factors. ............................................................................................................................................................................... 76

Figure 10-3 A diagram showing the site analysis during the month of May based on pedestrian and automotive factors. ............................................................................................................................................................................... 77

Figure 10-4 A diagram showing the development of the form based on site conditions as previously described. .......... 78

Figure 10-5 A study of the form development. These renderings begin to show the overall form from all directions. .......... 80

Hall of Fame Museum | 109

Figure 10-6 A site perspective shows the proposed museum in relation to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to the North and the Dallara Indycar Factory to the South. ........................................................................................................ 83

Figure 11-1 A top view rendering of the final form, which was developed from site conditions. ............................................. 86

Figure 11-2 A section view shows how the interior space is divided and experience by the visitors. ................................. 89

Figure 11-3 A section showing one iteration of how the collection can be displayed and organized. ................................. 91

Figure 11-4 A section showing another iteration of how the collection can be displayed and organized. This reflects the flexibility of the spaces. ................................................................................................................................ 93

Figure 11-5 A rendering showing the Main Street side of the new museum. ..................................................................... 95

Figure 11-6 A rendering showing the tailgating side of the new museum. ..................................................................... 97

Figure 11-7 A photograph of the final display boards displayed on the 4th floor of the Architecture Building. ...................... 98

Figure 11-9 An up-close view of the design iteration models with the descriptive diagram placed above. ...................... 99

Figure 11-8 An up-close view of the final 3D printed form model. ................................................................................. 99

Figure 11-10 The final presentation being given to a group of visiting jurors on April 28th, 2014. ............................... 101

Hall of Fame Museum | 111

References

(1909, May 28). Carl G. Fisher [Print Photo]. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003653845/ (“Carl G. Fisher,” Carl G. Fisher)

Bireley, E. (2013, October 11). Interview by D.S. Potash []. Discussing the current museum. (Bireley, 2013)

Bmw junior program. (2013, October 25). Retrieved from http://www.muenchen.de/int/en/sights/attractions/bmw-welt-munich/junior-program.html (“Bmw junior program,” 2013)

Bmw museum. (2013, September 21). Retrieved from http://www.atelier-brueckner.com/nc/en/projects/museums/bmw-museum-munich-germany.html?tx_photogals_elementid=7&tx_photogals_image=0 (“Bmw museum,” 2013)

Bmw welt / coop himmelb(l)au. (2009, July 22). Retrieved from http://www.archdaily.com/29664/bmw-welt-coop-himmelblau/ (“Bmw welt /,” 2009)

112 | Hall of Fame Museum

Bmw welt. (2013, September 20). Retrieved from http://www.bmw-welt.com/en/location/welt/concept.html(“Bmw welt,” 2013)

Davidson, D. (2005). Indianapolis motor speedway hall of fame museum. Lawrenceburg, IN: The Creative Company.

(Davidson, 2005)

Hall of fame museum. (2013, October 1). Retrieved from http://www.indianapolismotorspeedway.com/facility/35204-Museum/ (“Hall of fame,” 2013)

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (2001). The educational role of the museum. (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. (Hooper-Greenhill, 2001)

Kriscenski, A. (2007, November 14). Bmw welt: Solar-powered masterpiece in munich. Retrieved from http://inhabitat.com/bmw-welt-solar-powered-masterpiece-in-munich/ (Kriscenski, 2007)

Hall of Fame Museum | 113

Merz, H. (2010). Porsche museum. (pp. 185-364). New York, NY: SpringerWienNewYork. (Merz, 2010)

Otis. (Designer). (1909). Indianapolis motor speedway, greatest race course in the world [Print Graphic]. Retrieved from http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3g13593 (Otis, Indianapolis motor speedway, greatest race course in the world)

Ownership. (2013, October 1). Retrieved from http://www.indianapolismotorspeedway.com/history/35449-Ownership/ (“Ownership,” 2013)

Pagoda. (2013, October 1). Retrieved from http://www.indianapolismotorspeedway.com/facility/35548-pagoda/ (“Pagoda,” 2013)

Porsche museum. (2013, September 10). Retrieved from http://www.porsche.com/international/aboutporsche/porschemuseum/ test (“Porsche museum,” 2013)

114 | Hall of Fame Museum

Rosenblatt, A. (2001). Building type basics for museums. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (Rosenblatt, 2001)

Satterlee, R. (Photographer). (1966). Tony hulman and karl kizer in stodard-dayton car [Print Photo]. Retrieved from http://libx.bsu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/SatterleePh/id/783/rec/2 (Satterlee, Tony hulman and karl kizer in stodard-dayton car)

Should ims build a new hall of fame museum?. (2012, October 27). Retrieved from http://openwheelamerica.com/2012/10/27/should-ims-build-new-hall-of-fame-museum/ (“Should ims build,” 2012)

Vartiainen, H., & Enkenberg, J. (2013). Learning from and with museum objects: design perspectives, environment, and emerging learning systems. (Vartiainen & Enkenberg, 2013)

Hall of Fame Museum | 115

Daniel S

. Potash

RE

OR

GA

NIZ

ING

MU

SE

UM

AR

CH

ITEC

TUR

E: d

esigning a museum

for the indianap

olis motor sp

eedw

ay2014