Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

Transcript of Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

1/18

Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382

Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2009 DOI: 10.1163/157338410X12625876281505

CURRENT POLITICAL COMPLEXITIES OFTHE IRAQI TURKMEN

Jason E Strakes

School of Politics and Economics, Claremont Graduate University

Abstract

The Turkmen population of Iraq is a significant factor in linking the greater Cauca-sus region to Northern Mesopotamia. However, in the post-Saddam Hussein era,much conventional discourse has identified them as a politically and culturallymarginalised group in relation to the Arab and Kurdish majorities. This study pre-sents an alternative assessment of the Turkmen situation based on a survey ofchanges in the Iraqi political context over the past decade. This is applied in orderto determine the precedents for Turkmen democratic activity in northern Iraq, aswell as impediments to accommodation between Turkmen and other regional iden-tities. These patterns are analysed at both the domestic level, including geographic

distribution, popular mobilisation and party formation, and at the internationallevel, which examines the impact of Turkeys external influence and sponsorship onthese internal conditions. Several tentative conclusions are reached. First, the IraqiTurkmen exhibit both high levels of mobilisation and pluralistic political organisa-tion that contrast with other ethnic and sectarian minorities in Iraq. Second, sec-tarian and ideological cleavages within the Turkmen population along with sporadicviolent attacks have motivated assimilation with the coalition politics that hasevolved since the first post-Saddam national elections, rather than armed insur-gency. Finally, the role of Turkey as a primary external patron has presented bothobstacles and potential advantages for the political welfare of the Iraqi Turkmencommunity since 2003.

Keywords

Iraqi Turkmen, Northern Iraq, Ethnosectarian Identity, Political Mobilisation, Tur-key

INTRODUCTION

The present report provides a brief overview of the political situation of

a sizeable Turkic-speaking diaspora group in northern Iraq. It should,therefore, be regarded as a first cut rather than a definitive ethno-

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

2/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382366

graphic study, pending a more systematic treatment. The main conclu-sions, which should be drawn for investigative purposes are as follows.

First, the Turkmen are not necessarily as marginal a presence in post-2003 Iraq as some partisan or official sources have characterised themas being. While the Turkmen were granted legal recognition in the 2005Iraqi constitution, the degree to which their civil rights are protected inactual policy has been highly contentious in divided communities, suchas in Kirkuk (At-Tamim) province (Hasan 2005: 58) At the same time,the presence of multiple Turkmen political parties (both individual andcoalition), non-governmental organisations (NGOs), interest and cul-tural groups suggest that they are more mobilised and possibly betterrepresented than much smaller and more vulnerable identities, such asArmenians, Yezidis, Assyrian/Chaldaean/Syriacs, and Sabaean Mandae-ans. In particular, the role of Turkey in establishing and providing re-sources to Iraqi Turkmen organisations adds an international dimensionthat is comparatively lacking in the case of other Iraqi ethnosectarianminorities. Secondly, the Iraqi Turkmen do not necessarily constitute asingular identity, as both sectarian divisions (Sunni and Shia) andideological differences have also influenced their political orientation.Lastly, many Turkmen have become highly assimilated into the Arabmajority or Iraqi national identity.1Those Turkmen groups that are di-

rectly linked to or advocate solidarity with Turkey have a distinctagenda from those who regard themselves foremostly as rightful par-ticipants in the Iraqi national polity or the Kurdistan Regional Govern-ment (KRG).

AN ETYMOLOGICAL DIGRESSION

It is useful to first provide a background note on Iraqi Turkmen namingconventions. The Turkic population of northern Iraq (Irak Trkleri)is de-scended from the groups, which migrated to the region in ten major cy-

cles spanning A.D. 652-1535, from the Ubayyd and Abassid caliphates,the Akkoyunlu, Seljuk and Ottoman beyliks of Eastern Anatolia (Sunniand Alevi), and the Karakoyunlu and Safavid beylerbeyliks of northwestIran and the present-day Azerbaijan Republic (Shia/Qizilbash) (Hazar2007: 359-361). They, therefore, originate from a different branch ofthe Ouz tribal confederation than the Central Asian Turkmen, which

1 For instance, the Turkic-Mongol Piawut tribe, which settled in the SuleymanBeg/Amirli sub-district (nahia) of Tuz Khormatu near the Hamrin mountain range

in the 13th century, eventually became ethnically and linguistically integrated withmigrating southern Arab tribes to form al-Bayat, one of the largest and most promi-nent Iraqi kinship groups (see Talabany 2001: 56).

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

3/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382 367

are the titular majority in the former Soviet republic of Turkmenistanand also inhabit northwest Afghanistan and the north-eastern prov-

inces of Iran. This distinction has led to confusion in the multiple usagesof Turcoman, Turkomen, Turkman and Turkmen, which is rooted in con-trasting English, Arabic, and Persian pronunciations, conflicting inter-pretations and translations by various Turkic scholars, and the disputebetween Great Britain and Turkey on the nationality status of formerOttoman Turkish citizens in the vilayet of Mosul during the mid-1920s(Nissman 1999; Petrosian 2003: 279; Pashayev 2005). However, theterm Turkmenhas become the standard usage among both the Multi-Na-tional Force-Iraq and international aid and development agencies since2003, and is, therefore, the one used in this report.

RESEARCH STRATEGY

An analysis of the role of the Turkmen minority in reconstructing coop-erative political association in northern Iraq must first take into ac-count several major concerns. First, while there is a significant body ofobjective scholarly resources on the Turkmen population of Iraq, par-ticularly those authored by Turkish and Azerbaijani academics(see Pa-shayev 2003: 24-25; Gl 2007; and bibliography in Kayl 2008), it

must be noted that a large amount of publicly available literature onthis subject is highly partisan and biased. Those publications producedby expatriate advocacy groups, such as the Netherlands-based IraqiTurkmen Human Rights Research Foundation (SOITM), which functions intandem with the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO),and the New York Turkmen Institute (NYTI) are typically focused onproving the predominance of the Turkmen in terms of both popula-tion size and historical importance, as well as promoting a narrative ofvictimisation, charges of distortion and demands for recompense, whichreflects similar activities and arguments on the part of Kurdish andAssyrian advocates.2For instance, one of the primary platforms of theinternational Iraqi Turkmen movement is that they have been politi-cally marginalised because their true number in Iraq has been deliber-ately underreported or falsified by the former regime, the leadership ofIraqi Kurdistan and the United States.3There is little consensus on the

2At the same time, it should be mentioned that these organisations also providea wealth of open-source historical information on northern Iraqi cultures thatwould be otherwise inaccessible to English speakers.

3

Event Summary, Rethinking Iraq: Sectarian Identities

The Turkmen, Middle EastInstitute, Washington D.C., April 15, 2004, .

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

4/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382368

actual relative size of the Turkmen population, with various divergentfigures reported by previous Iraqi government ministries (Ylmaz 2006:

130-131; Ouzlu 2004: 312-313; Bruinessen 2005: 54, fn. 7).Althoughthe 1957 census, one of the few reliable data sources on the demo-graphics of Kirkuki ethnicities, placed the Turkmen population atroughly 570,000, advocates claim that they constitute from two to threemillion of the total national population. Despite these conflictingclaims, it is generally agreed that the Turkmen constitute the thirdlargest Iraqi ethnic group behind Arabs and Kurds.

In order to assess the future political prospects of the Iraqi Turkmen,it is also necessary to consider the role of external actors, especially the

sponsorship of Turkmen political parties and interest groups by boththe government of Turkey and Turkish NGOs. Certain of these interna-tional forces recognise the Turkmen identity in Iraq as a territorial, aswell as an ethnic and cultural entity, which complicates the effort of in-troducing new mechanisms for conflict resolution in Kirkuk and theadjacent areas. Additionally, the concern for determining the Turkmenrole in resolving land disputes and adequate political representation di-rectly relates to the difference between conditions in Mosul/Ninewaand Kirkuk, which are highly contested between Kurds and other mi-nority groups, and the relatively more stable and evolving democratic

politics of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).Therefore, this report will approach the issue of what position the

Turkmen occupy in the post-2003 Iraqi context by focusing on two pri-mary research questions: 1) what are the recent historical precedents ofa Turkmen role in fostering a pluralistic political environment in north-ern Iraq, and 2) what are the current conditions, which present obsta-cles to reestablishing accommodation between Turkmen, Kurd, Araband other identities? Each of these foci will be examined at the domesticand international levels.

THE CULTURAL GEOGRAPHY OF IRAQI TURKMEN

In order to place the presence of the Iraqi Turkmen in perspective, it isuseful to identify the territorial context of Turkmen habitation in rela-tion to the Kurdish region of northern Iraq. The geographic basis of thelocal Turkmen identity is an informally defined area that directly inter-sects central Iraqi Kurdistan, running in a northwest by southeast pat-tern between the 32nd and 37th parallels (see Figure 1) (Ouzlu 2001:

13; Petrosian 2003: 280). This area stretches from the Al-Jazirah plainbordering Syria to the southwestern frontier of Iran in Diyala province.

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

5/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382 369

Major Turkmen population and cultural centers range from the cities ofTal Afar, Mosul, Erbil, and Kirkuk (Ylmaz 2006: 131), to relatively

smaller settlements of Altin-Kyopru, Sanjar, Daquq (Tavuq/Tauq), andTuz Khurmatu, to portions of Bayat, Kifri, Qara Tepe, Kizlarbat, Kha-naqin, Shahriban, al-Mansuriye, Deli Abbas, and Kazaniya, and termi-nate at Mendeli and Bedre along the Diyala-Iran border (Ylmaz 2003:25-26;Ouzlu 2004: 313). The historic Turkmen identity of several ofthese areas has been diluted through absorption of the prevailing Arab(or in some locales Kurdish) language and culture, emigration duringpast conflicts and political integration with the central government.4Inparticular, Tuz Khormatu is known as the population centre of the

Arabised Turkmen al-Bayati tribe.

5

In addition, there is a significantconcentration of assimilated Arabic-speaking Turkmen in Baghdad(Ouzlu 2004: 313).

This dispersed population belt is especially significant in that it iscentrally located between the Kurdish and Sunni Arab-dominant re-gions of Iraq (Ouzlu 2004: 313). A necessary point of departure in ananalysis of inter-ethnic relationships in Salah ad-Din province is that al-though the cities of Tuz Khormatu and Amirli in Tuz district (qadaa)have been known as centres of Turkmen society since the Ottoman pe-riod, the remaining divisions are predominantly Sunni Arab, with a mi-nority Shia Arab population. The presence of a northern Iraqi Kurdishidentity in this area is mainly an artefact of administrative engineeringby the Baath regime, which separated the municipality of Tuz Khor-matu from Kirkuk province and attached it to northeast Salah ad-Din in1976. The demographic effect of this boundary relocation has been acomplex pattern of Shia Turkmen-majority urban quarters, and smallertownships (nahias) whose populations are sharply divided betweenKurdish and Sunni Arab minorities (Kerkuklu 2008: 18, 27-28).6

Perhaps the most complicated aspect of these demographic patterns

is that while major urban municipalities, such as Mosul, Erbil, andKirkuk were historically Turkmen-dominant, the rural lands of the sur-rounding province were inhabited predominantly by Kurds and otherethnic and sectarian identities. While Iraqi Turkmen nationalists and

4ORSAM, The Forgotten Turkmen Land: Diyala, Report No: 7 November 2009: 7-9.5ORSAM, The Tuzhurmatu Turkmens: A Success Story, Report No: 6 November 2009:

7-8.6 See also International Organization for Migration, Salah Al-Din Emergency Needs

Assessment, Post-February 22 Emergency IDP Monitoring and Assessments, Novem-ber 16, 2006: 1-2, .

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

6/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382370

their Turkish sponsors have recently defined this area as a politicalzone known as Turkmeneli (Turkmen Land) (Bruinessen 2005: 52)

(see Figure 1), unlike the Kurdish Autonomous Region from 1970 to 1991and KRG from 1992 to present, there is no historical precedent of de-marcation or administration of a distinct Turkmen polity in Iraq. SomeTurkish advocates have suggested that because the U.S. military inter-vention has permanently altered the traditional Iraqi nation, the Turk-men parties must abandon the ethic of preserving the countrys territo-rial integrity and adopt a policy of declaring an independent state (Oz-pek 2006).

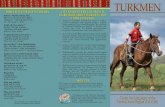

Fig. 1 Arabic Language Depiction of Turkmenli (Bruinessen 2005)

In contrast, one administrative unit that has remained an essentiallyhomogenous (and the most densely populated) Turkmen territory is thecentral area of Tal Afar qadaa in northern Ninewa province (Erkmen2009: 25).7 Save for the Kurdish-populated northern nahia of Zummar,

7See also International Crisis Group, Iraqs New Battlefront: The Struggle Over Nine-wa, Middle East Report No 90, 28 September 2009: 33-34.

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

7/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382 371

the area has remained exempt from the territorial claims of the KRG,and thus presents the most realistic platform for a separate Turkmen

authority for nationalist forces (Erkmen 2009: 33). This situation has de-veloped in tandem with the secession of multiple districts and settle-ments from the jurisdiction of the Ninewa provincial government sincethe victory of the Sunni Arab al-Hadbaa party in the January 2009 localelections (Al-Iraq 2009). The Turkmen population of Tal Afar is dividedbetween a Hanafi Sunni majority and a Shia minority (estimated atroughly 60/40 percent; cf. Erkmen 2009: 26), a smaller sub-group (10percent; seeBayatl2005) of which are Alevi-Bektai/Mavili and sharekinship ties with the nomadic clans of Anatolia (Telaferli 2009: 35-36).

Religious differences are not central in custom as all three affiliationsmay cut across a single tribe or kin group; nor have Shia Turkmen be-come politicised as elsewhere in Iraq, as local clerical authorities advo-cate quietism and cooperation (Erkmen 2009, 27-28). However, duringthe multi-faceted Iraqi insurgencies that transpired from 2004-2008, theoutside influence of radical Sunni Islamist and Sadrist groups engen-dered violent clashes between Turkmen sects that are still in the proc-ess of being settled (Erkmen 2009: 31-32). Despite this condition, localleaders assert that it is the lack of sufficient social services, infrastruc-ture and security rather than sectarian divisions that seriously affectsthe quality of life in the community (olak 2009: 53-54).

TURKMEN POLITICAL IDENTITY IN NORTHERN IRAQ: DOMESTIC FACTORS

The Turkmen are specifically acknowledged in the Preamble and Article4 and 121 of the 2005 Iraqi Constitution, which grant recognition andlanguage rights to ethnic minorities.8However, the delayed status of thenormalisation process, which was supposed to have been implementedin Kirkuk under Article 140, and the dominance of the provincial coun-

cil by Kurdish representatives (26 out of 41 seats) since the January 2005elections has created a significant dynamic of tension in the province.However, the Turkmen are only one minority group that has resistedmarginalisation in Kirkuk. Further, they possibly enjoy better represen-tation than other minorities in national politics, due to their compara-tively larger number and their pragmatic participation in coalitionswith Shia Arab parties, such as the United Iraqi List/Alliance (UIA) andthe Sadrist Movement (Barkey 2009: 17). The Shia Turkmen population

8

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Final DraftIraqi Constitution, 30 January 2005: 1, 3, 29, .

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

8/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382372

of Tuz Khormatu has played a particularly significant role in the Isla-mist opposition, as many that fled to Iran during the 1980-1988 Persian

Gulf War became active in exile movements, such as the Islamic CallParty (al-Dawa) and the former Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolu-tion in Iraq (SCIRI), returning to hold leadership positions in the post-Baath era.9

In addition, there is a large proliferation of Turkmen parties and in-terest groups in Iraqi Kurdistan, many of which cooperate with the pre-vailing Kurdish authorities. As of 2006, four representatives of theTurkmen Party occupied seats in the Kurdistan Parliament-Iraq (for-merly the Kurdistan National Assembly): Asad Shakir Amin, Soham An-war Wali, Talad Mohammad Saleh Toufiq, and Karkhi Najmadin Nou-ri.10 Lastly, there is a divergence between those Turkmen groups thatclaim solidarity with the pan-Turkic ideological movement based inTurkey and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) (and to alesser extent Azerbaijan), and those that reject foreign sponsorship andinfluence and seek greater political integration and equal representa-tion within the KRG.

The evolution of Turkmen political mobilisation in Iraq must beviewed in the context of the shifting distributions of power and influ-ence that have occurred over an 80-year period from the dissolution of

the Ottoman Empire in the early 1920s, to the ascendance of the Baathregime in the 1960s, to the consolidation of the federal Kurdish regionsince 2003. During the Ottoman period, Sunni Turkmen made up theadministrative elites of many major cities in Iraq, particularly in Mosuland Kirkuk (Bruinessen 2005: 51). This privileged position in the north-ern provinces began to be altered in the period between the establish-ment of the British Mandate from 1921-1923 and independence underthe Hashemite monarchy from 1932-1958, in which Sunni Arab influ-ence gradually became predominant (Bruinessen 2005: 51). The first

public organisation specific to Turkmen interests, the Turkmen Brother-hood Association, was formed in 1960, and served as a community serviceunion rather than as a political party. However, over the next two dec-ades it became increasingly involved in clandestine opposition activi-ties, resulting in suppression by the Baathist government in 1977 andthe purging of its participants in 1980.

9ORSAM, The Tuzhurmatu Turkmens: A Success Story: 12.10

Kurdistan Regional Government. Members of the Kurdistan National Assembly asof August 2006: 3, http://www.krg.org/uploads/documents/KNAMembers__2006_11_30_h12m44s8.pdf.

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

9/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382 373

The initiation of a party-based Iraqi Turkmen opposition was con-siderably delayed in comparison to the longstanding Shia Arab move-

ments, as the first formal groupings were initiated only in the late 1970sbeginning with the ineffectual National Democratic Organisation (Yl-maz 2003: 26-27). Yet, in the period following the Second Persian GulfWar of 1991, the proliferation of Turkmen parties progressed rapidly.The first major opposition party conventions were held externally inBeirut, Lebanon in 1991 and Vienna, Austria in 1992, followed by ameeting of Turkmen constituents of the Iraqi National Congress (INC)coalition of exile groups in Salah ad-Din the same year (Ylmaz 2003: 26-27).

Fig. 2 Flag of Turkmen National Congress(Martins-Tuvlkin 2007)

The Turkmen National Congress (Kurultay) was an umbrella organi-sation established through a memorandum of understanding concludedon 5 February 1997 between the six previously existing Turkmen partiesand interest groups that constitute the Iraqi Turkmen Front ((Irak Trk-men Cephesi/ITC)), as represented on its flag by the six stars linking thetwo horns of the crescent (see Figure 2) (Petrosian 2003: 292). These in-

cluded the Iraqi National Turkmen Party (INTP), which was founded in1988 and later operated in the northern Iraqi no-fly zone establishedafter the Persian Gulf War (see Figure 3), the Turkmeneli Party, theTurkmen Independence Movement, the Turkmen Brotherhood Associa-tion (Ocak), the Turkmeneli Cooperation and Culture Foundation (An-kara), and the Iraqi Turks Culture and Assistance Association (Istanbul)(Petrosian 2003: 292). The First Iraqi Turkmen conference that was heldin Erbil from 4-7 October 1997 represented an effort to reconstitute theopposition movement after the Baghdad military offensive against theKurdish Democratic Party (KDP) on 31 August 1996, in which Turkmenparty offices were raided and shut down (Nissman 1999). The founda-

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

10/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382374

tional activity of the Kurultay was the drafting of the Declaration ofPrinciples, which presented a formal definition of the Iraqi Turkmen

identity (Nissman 1999). One of the most important provisions (Article3) identifies the circumstances that motivated the Turkmen movement.This asserted that because of the lack of consensus on their ethnic andlinguistic identity between the communities of Iraq, Turkey, Iran, Azer-baijan, and Turkmenistan, the Iraqi Turkmen have frequently beensubject to external forces rather than their own initiative (Nissman1999). The meeting also established several basic institutional struc-tures of the organisation, including a framework of by-laws, an elected30-member Supreme Congress that selects the president and member-ship of the Executive Board, and procedural rules for conducting futureelections (Petrosian 2003: 292). Elections for the composition of theBoard drew representatives from four of the constituent parties in addi-tion to the Turkmeneli Cooperation and Culture Foundation (TCCF), anNGO based in Ankara (Petrosian 2003: 292).

Fig. 3 Flag of Iraqi National Turkmen Party (Martins-Tuvlkin 2007)

The second Kurultay was held from 20-22 November 2000, which

elected Sanan Ahmad Agha as President. However, this Congress waspublicly opposed by several Kirkuk-based parties, including the Turk-men Brotherhood Forum, the Iraqi Turkmen United Party, the TurkmenNational Salvation Party, the Iraqi Turkmen Brotherhood Party, theTurkmen Cultural Association in Iraqi Kurdistan, and the KurdistanTurkmen Party (Nissman 2000). These entities charged that the ITC rep-resented the interests of the Turkish government rather than those ofindigenous Turkmen. In 2002, the Iraqi Turkmen Union Party (ITUP)was formed, which maintained neutrality between Turkish-sponsoredand domestic Turkmen opposition groups, but at the same time recog-nised the KRG as the legitimate authority of northern Iraq and rejected

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

11/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382 375

the establishment of an independent Turkmen militia (Petrosian 2003:296). In November 2002, four of these groups formed the Turkmen Na-

tional Association, which presented a platform of accommodation andintegration within the structures of the KRG rather than nationalist af-filiation with Turkey.11Other major cleavages have developed in recent

years between the Erbil and Kirkuk wings of the ITC, which resulted inthe defection of the KRG branch led by Abdul Qadil Bazirgan at thefourth Kurultay in April 2005, and the formation of the Turkmen De-mocratic Movement and Independent Turkmen Group in January 2004and June 2006 (Anderson/Stansfield 2009: 197).

Another significant independent Turkmen opposition entity is theShia Islamic Union of Iraqi Turkmen (IUIT), which was formed in 1991as part of the exile-led INC, and initially endorsed ethnic and sectarianpluralism (Nissman 1999). The IUIT has since participated in thebroader mobilisation of Iraqi Shia that began in 2003, and joined theUIA during the January and December 2005 provincial and legislativeelections (Bakovic 2005: 5). The amended national elections law passedby the Iraqi Council of Representatives in November 2009 also reflectsthis tendency for assimilation into broad party lists and coalitions.While the provisions allot compensatory seats for minority representa-tives including Assyrian/Chaldaeans, Yezidis, Shabaks, and Sabaean

Mandaeans, the absence of accommodations for Turkmen may be ex-plained by the fact that no Turkmen candidates or parties are cam-paigning independently for the 2010 national elections.12

ABSTENTION FROM VIOLENT ACTIVITY

An additional distinguishing factor in Iraqi Turkmen politics is that savefor the 1920 anti-British uprising at Tal Afar (Kaaka Destan)(Al-Wardi1992: 160; Hrmzl 2009: 31-38), they have historically not partici-

pated in armed resistance or insurgency (Ylmaz 2006: 129-130), despitethe establishment of self-defense militias by nationalist parties, such asITC, which reportedly maintains a security force of 500 personnel. Oneexplanation extended by strategic analysts is that unlike the mountain-ous terrain of Iraqi Kurdistan, which provided a tactical advantage tothe Kurdish Peshmerga guerillas against the Iraqi armed forces between

11Profile: Turkoman Parties, BBC News, Monday, 13 January, 2003, 17:20 GMT,.12Open Source Centre: Iraqi Council of Representatives, Iraq: Parliament Posts Textof Amended Elections Law, 08 Nov. 2009, GMP20091109641002.

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

12/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382376

1963 and 1975, the geography of the Turkmen region consists largely oflevel plains and desert, which has limited the feasibility of resorting to

irregular armed actions to defend their interests (Ouzlu 2001: 23).While some evidence of Turkmen participation in the post-2003 insur-gency has been presented by media sources (including an allegedbombing plot by former ITC leader Sanan Ahmet Aa, directed at Kurdsand U.S. troops), it remains unclear whether it is independent from thegeneral sectarian violence that has occurred in unstable cities, such asKirkuk (Bakier 2008). In particular, the incidence of bombings and otherarmed attacks in northern Iraqi districts have recurrently precipitatedcalls for the establishment of a professional Turkmen paramilitary toprotect the population from insurgent and terrorist activity.13

TURKMEN POLITICAL IDENTITY IN NORTHERN IRAQ: INTERNATIONAL FACTORS

Beginning in the mid-20th century, the international politics of theMiddle East and Caucasus regions have often been characterised by in-tervention in the affairs of neighbouring states in order to protect theinterests of a shared ethnic identity. This has been clearly exemplifiedin the history of republican Iraq, in which domestic actors have fre-quently been linked to external groups and influences, such as Kurds

with Syria, Turkey and Iran, Shia Arabs with Iran, and the Turkmenwith Turkey (etinsaya 2006: 1). In the decade between the 1991 GulfWar and the 2003 Coalition invasion, Ankara initiated a foreign policythat identified northern Iraq as a central security (i.e., the KurdishWorkers Party) and economic (i.e., cross-border shipping and aid deliv-ery) concern, in which conditions in the Iraqi Kurdish territories had aninterdependent effect on Turkeys national welfare (Demir 2007: 197-198). This orientation became closely connected to Ankaras relation-ship with the Turkic diaspora in the region (Hasan 2003: 175-190).

TURKEYS INFLUENCE ON TURKMEN POLITICAL MOBILISATION

Since the initiation of the Iraq War in 2003, the government of Turkeyhas had strong incentives to provide diplomatic support to the nation-alist Turkmen opposition (etinsaya 2006: 1). However, this has con-flicted with its original foreign policy priority of preventing the forma-tion of an independent Kurdish polity by preserving the territorial

13

In 2009 alone, Turkmen communities experienced major suicide bombings atTuz Khurmatu and Tal Afar, followed by the assassination of ITC provincial repre-sentative Yavuz Efendiolu in Mosul.

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

13/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382 377

status quo in northern Iraq (Ouzlu 2002: 141). At the same time, therehave been significant patterns of forced migration by Iraqi Turkmen

(almost one tenth of the total population) to Turkey due to conflict andinsecurity and strong cultural affinities, as a majority of Iraqi Turkmenenjoyed relatively high educational and income status during the Baathera (Sirkeci 2005a: 27-28). Additional survey-based evidence suggeststhat while migrated Turkmen in Istanbul and Ankara have enjoyed rela-tively better educational and economic opportunities as opposed to im-proved cultural and religious freedoms, the associated practical difficul-ties of relocating offer limited incentives to migrate for the remainingIraqi Turkmen population (Sirkeci 2005b: 5-10).

In the period following the collapse of the former regime, the mostsignificant dynamic that developed within the Turkmen movement wasa division between the leading bloc of interest groups that were directlyaligned with Turkey, and the independent Turkmen opposition parties,which sought equal representation within the administrative structuresof the KRG. Since the mid-1990s, the ITC has served as the most promi-nent Turkmen nationalist organisation in contemporary Iraq, and isgenerally believed by Western observers to have been established bythe Turkish Special Forces(Bordo Bereliler) in Ankara and Erbil in April-May 1995 as a counterweight to aspirations for independence by the

Kurdish leadership (Jenkins 2008: 14-15). Turkish observers, however,have interpreted its formation in a more benevolent light, as repre-senting a shift in Ankaras policy from providing limited humanitarianaid to securing Turkmen political solidarity (Ylmaz 2006: 141). This in-terpretation also highlights the Turkish role in negotiating a cease-firein the internal Kurdish conflict of 1994-1996, which included plans toprovide the Turkmen with training and weapons to support peace keep-ing activities in northern Iraq (Ylmaz 2006: 141).

An additional dimension of external influence has been the coopera-

tion initiated between Turkey, the ITC and representatives of the Arabstates in counterbalancing the potential expansion of the KRG. This wasrepresented by a January 2004 press conference involving then ITCchairman Faruk Abdullah Abdurrahman, Egyptian Foreign MinisterAhmet Mahir and Arab League Secretary General Amr Musa in Cairo,Egypt, which was given significant exposure by Arab media outlets (Y l-maz 2006: 136). The meeting also produced a group statement publiclyopposing the establishment of a Kurdish federal region in Iraq.

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

14/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382378

While some sources assert that ITC was originally composed of asmany as 26 individual organisations,14its main current constituents are

the INTP, the Turkmeneli Party, which was founded in 1992 in NorthernCyprus as the Turkmen Union Party, the Provincial Turkmen Party, theMovement of the Independent Turkmen, the Iraqi Turkmen RightsParty, and the Turkmen Islamic Movement of Iraq. The platforms ofseveral of these groups diverge according to their political objectives.While the INTP seeks to establish an autonomous Turkmen regionanalogous to Iraqi Kurdistan, Turkmeneli seeks to secure federal regionsfor the four largest Iraqi ethnic groups, while Independent Turkmenadvocates the establishment of a sovereign Turkmen state (Ylmaz 2006:136). The INTP and Turkmeneli positions are strongly supported by theTurkish government, which regards the ITC as representing its interestsin Iraq and has provided diplomatic, military and intelligence backingsince its establishment in the mid-1990s (Rubin 2005). However, sincethe national Iraqi elections of January and December 2005, the ITC hasenjoyed little popular support among Iraqi Turkmen citizens. On 30

January 2005, ITC candidates won only 0.87 percent of 8,5 million votescast, or a total of three seats in the former Iraq National Assembly (Bar-key 2005: 7). There is additional evidence, such as that reported by in-dependent Turkish journalists, that there is significant resistance to

Ankaras political and military influence among local Iraqi Turkmenleaders.

TURKEYS INFLUENCE AND TURKMEN CULTURAL GEOGRAPHY

However, two areas in which the relevance of the ITC (and by extension,the external role of Turkey) has experienced a potential renaissance arein Tal Afar and Tuz Khormatu qadaas. The geographic location of TalAfar has been identified for its strategic significance as a crossroads be-

tween Iraq, Syria to the west and Turkey to the north, as a buffer zonebetween the Syrian Kurds and the KRG, and a singular domain for coop-eration between Turkmen, Arabs and Turkey independent of the pro-vincial government (Erkmen 2009: 24-25). In addition, the territoryserves as a transit route for the Kirkuk-Ceyhan oil pipeline.15While localsupport for the ITC declined steadily during the Coalition occupation, in2007 it established a new regional office, and by fielding candidates for

14 International Crisis Group, War In Iraq: Whats Next For The Kurds? Middle East

Report No 10, Amman/Brussels, 19 March 2003: 7, .15International Crisis Group, Iraqs New Battlefront: The Struggle Over Ninewa: 33.

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

15/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382 379

the January 2009 elections on the influential al-Hadbaa list, won repre-sentation on the Ninewa provincial council by a narrow percentage of

votes. Similarly, Tuz Khormatu serves both as a buffer between theSunni triangle (Baghdad, Ramadi and Tikrit) and the Kurdish territo-ries, and as an intersection between the Turkmen communities of Kir-kuk and Diyala, while in the local elections ITC candidates won twoseats on the Salah ad-Din provincial council, earning over 40 percent ofthe total number of votes cast in the district.16An expansion of Turkishpolicy in these sub-regions would involve increasing development aidand investment, building on activities, such as the supply of Turkish-language books to local schools and education of students in Turkey, re-ceipt of residents for medical treatment in Turkish hospitals, and theprovision of training for local physicians through the Turkish Interna-tional Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA) (Erkmen 2009: 12).Thus, in contrast with the common public debate regarding Ankarasmilitary and intelligence involvements in northern Iraq (i.e., the redlines separating Turkey and the KRG), such possibilities recall earliercommentary on Turkeys proper role in relation to the Iraqi Turkmenafter the 2003 War: to take advantage of its position as a regional powerto better promote their interests through endorsement of internationallegal provisions and requirements pertaining to human and cultural

rights, criminal justice, and conflict resolution (Hasan 2005: 49).

CONCLUSION

The presence of ethnic and linguistic groups of non-Arab origin in Iraqadds complexity to the conventional conception of the Arab MiddleEast. The Iraqi Turkmen represent a third national identity group be-hind the dominant Arab and Kurdish populations, each of whom havesought to redefine their position in the Iraqi polity since 2003. However,

rather than either isolation or pan-Turkic nationalism, during this pe-riod many Turkmen have exhibited a high degree of socio-cultural as-similation and accommodation with broader political trends, particu-larly among citizens that reside within the de jure boundaries of theKRG. At the same time, the existence of a regional patron state and itssubsidiary organisations has also fostered a contradictory dynamic inTurkmen ethnic identification across regions of the country. The evi-dence suggests that while Turkmen may be receptive to the role of theTurkish-sponsored front in more homogenous communities that stand

16ORSAM, The Tuzhurmatu Turkmens: A Success Story: 6, 11.

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

16/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382380

to benefit from external support, those Turkmen populations embeddedwithin societal majorities have tended to reject ideological solidarity in

favour of national integration.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Al-Iraq, Aswat (2009), Talafars Residents Demand its Separation fromNinewa, May 28, .

Al-Wardi, Ali (1992), Lamahat ijtimaiyya fi tarikh al-Iraq al-hadith [SocialAspects of the Modern History of Iraq], London, Dar Fufan, vol. 1.

Anderson, Liam; Stansfield, Gareth V. (2009), Crisis in Kirkuk: The Eth-nopolitics of Conflict and Compromise, University of PennsylvaniaPress.

Bakier, Abdul Hameed (2008), Iraqi Turkmen Announce Formation ofNew Jihadi Group, The Jamestown Foundation, Terrorism FocusVolume, 5 Issue, 11 March 18, .

Bakovic, Danilo (2005), IRI Brief Guide to Iraq General Elections December

2005, Baghdad, December 5, .

Barkey, Henri J. (2005), Turkey and Iraq: The Perils (and Prospects) ofProximity, United States Institute of Peace, Special Report 141, July,.

(2009), Preventing Conflict in Kurdistan, Carnegie Endowment forInternational Peace, .

Bayatl,Nilfer (2005), Trkmen ehri Olan Gazi Telaferin Tarihesi, KerkkVakf, .

Bruinessen, Martin van (2005), Kurdish challenges, Walter Posch (ed.),Looking into Iraq, Chaillot Paper No. 79, European Union Institutefor Security Studies, July, .

etinsaya, Ghkan (2006), The New Iraq, Middle East and Turkey: A TurkishView, SETA Foundation for Political, Economic and SocialResearch, Report No. SE1-406, April, .

olak, Riza (2009), There Is No Such Issue As The Sunni-Shiite ConflictIn Talafar,Ortadou Analiz,Mays, cilt 1, say5.

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

17/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382 381

Demir, dris (2007), The Northern Iraq: 1990-2000, ZKSosyal BilimlerDergisi, cilt 3, say5

Erkmen, Serhat (2009) Iraqs Pivotal Point: Talafar, ORSAM Center ForMiddle Eastern Strategic Studies,Report No: 3, May.

Gl, Ycel (2007), The Turcomans and Kirkuk, Philadelphia, PA: XlibrisCorporation.

Hasan, Mazin (2003), Trkmenler, Trkiye ve Irak: Krfez SavandanIrakn galine Trkmenlerin Durumu, Avrasya Dosyas, K,Kollektif, say: 4 cilt: 9: 175-190.

(2005), Irak trkmenlerinin barii politikalari ve sonulari,Stratejik analiz,Avrasya Stratejik Aratrmalar Merkezi (ASAM), Ekim.

Hazar, Mehmet (2007), Irak Trkmenler Dn ve Trkes, TurkishStudies, volume 2/2: 359-361.

Hrmzl, Habib (2009), Turkmen City Talafar and First Uprising AgainstOccupation in Iraq, Ortadou Analiz, Mays, cilt 1, say 5, .

Jenkins, Gareth (2008), Turkey and Northern Iraq: An Overview, TheJamestown Foundation, Occasional Paper, October, .Kayl, Ali Gkhan (2008), The Iraqi Turkmen: 1921-2005, Kerkk Vakf,

stanbul.

Kerkuklu, Mofak Salman (2008), The Turkmen City of Tuz Khormatu,Ireland, Dublin, .

Martins-Tuvlkin, Antnio (2007), Flags of the World (FOTW), December 9.

Nissman, David (1999), The Iraqi Turkmen: Who They Are and WhatThey Want, RFE/RL Iraq Report, 5 March, volume 2, No 9, . (2000), Turkmen Front Congress Concludes, RFE RL, IRAQ

REPORT, vol. 3, Number 40, .

Ouzlu, H. Tark (2001), The Turkomans of Iraq as a Factor in TurkishForeign Policy: Socio-Political and Demographic Perspectives,D Politika EnstitsForeign Policy Institut, Ankara, . (2002), The Turkomans as a Factor in Turkish Foreign Policy,

Turkish Studies, vol. 3, No. 2.

-

7/24/2019 Current Political Complexities of the Iraqi Turkmen

18/18

J. E. Strakes / Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009) 365-382382

(2004), Endangered Community: The Turkoman Identity inIraq,Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, vol. 24, No. 2.

Ozpek, Burak Bilghehan (2006), Turcoman Lebensraum in Iraq, GlobalStrategy Institute, 24 May, .

Pashayev Gazanfar (2003), Links to Turkmen in Iraq: Azerbaijanis inIraqLittle Known People,Azerbaijan International, Spring (11.1).

(2005), A Brief View on History, Dialect and Folklore of IraqiTurkmans, USAK, July 6.

Petrosian, Vahram (2003), The Iraqi Turkomans and Turkey, Iran andthe Caucasus, vol. 7/1-2: 279-308.

Rubin, Michael (2005), A Comedy of Errors: American-Turkish Diplo-macy and the Iraq War, Turkish Policy Quarterly, Spring. .

Sirkeci, Ibrahim (2005a), Turkmen in Iraq and International Migration ofTurkmen, Global Strategy Institute, Ankara, January, .

(2005b), Conflict and International Migration: Iraqi Turkmen inTurkey, Paper presented at XXV IUSSP International Population

Conference, Tours, France18-23 July; Session No: P5, .

Talabany, Nouri (2001), The Arabization of the Kirkuk Region, 2nd Edition,Uppsala, Sweden, .

Telaferli, Ahmet (2009), Trkmen Kenti Telafer, Kardalk, Nisan-Hazi-ran, cilt/yl 11, say42.

Ylmaz, Hasan (2003), Irakn Gizlenen Gereni: Trkmenler, StratejikAnaliz,Avrasya Stratejik Aratrmalar Merkezi (ASAM), Mays.

Ylmaz, lhan (2006), Gemiten Gnmze Irakta Trkmen Politikasi,TTAD,V/12.