CSR ellen

-

Upload

ali-farooq -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

0

Transcript of CSR ellen

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

1/12

cademy ol Management Review2 0 0 1 , Vol. 26 , No. 1, U7-12 7 .

NOTECORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY:A THEORY OF THE FIRM PERSPECTIVE

ABAGAIL MC WILLIAM SUniversity of Illinois at C hicag oDONALD SIEGELUniversity of Nottingham

We outline a supply and dem and m odel oi corporate social responsibility(CSR).B ased onthis framework, we hypothesize that a firm's lev el of CSR will d epend on its size, level ofdiversification, research and developm ent, advertising, government sa les, consumer in-come, labor market conditions, and stage in the industry life cy cle. From these hypothe-ses, w e conclude that there is an ideal level ofCSR, which managers can determine viacost-benefit an alysis, and that there is a neutral relationship between CSR and financialperformance.

M a n a g e r s c o n t i n u a l l y e n c o u n t e r d e m a n d sf rom mul t ip le s takeholder groups to devoter e sourc es t o co rpora t e soc i a l r e spons ib i l i t y(CSR). These p res sur es e me rge f rom cus tom-ers, employees , supp l i e r s , communi ty g roups ,gove rnment s , and some s tockho lde r s , e spe -c i a l l y i n s t i t u t i o n a l s h a r e h o l d e r s . W i t h s omany confl ict ing goals and object ives , the def-ini t ion of CSR is not always clear . Here wedef ine CSR as ac t ions tha t appear to fur thersome socia l good, beyond the in teres t s of thefirm and that which is required by law. Thisdef ini t ion underscores tha t , to us , CSR meansgo ing beyond obey ing the law. Thus , a com-p a n y t h a t a v o i d s d i s c r i m i n a t i n g a g a i n s twomen and minor i t i es i s not engaging in asocia l ly respons ible ac t ; i t i s mere ly abidingby the law.

Some examples of CSR act ions include goingbeyond legal requi remen ts in adopt ing p rogres-s ive human resource management programs ,developing non-animal tes t ing procedures , re -cyc l i ng , aba t i ng po l l u t i on , suppor t i ng l oca lbus inesses , and embodying products wi th so-cial at t r ibutes or characterist ics . We l imit thescope of our analysis to sat isfying the burgeon-ing demand for CSR through the creat ion ofproduct at t r ibutes that direct ly support socialresponsibility (e.g. , pesticide-free produce) orthat signal the firm's commitment to CSR (e.g. ,dolphin-free-tuna labels) .

Many managers have responded to he ight -ened stakeholder interest in CSR in a very pos-i t ive way, by devoting addit ional resources topromote CSR. A primary reason for positive re-sponses is the recognition of the relevance ofmu l t ip le s takeh olders (Donaldson Pres ton ,1995; Mitchell , Agle, Wood, 1997). Othe r ma n-agers have a less progressive view of stake-holder relevance. They eschew at tempts to sat-isfy demand for CSR, because they bel ieve thatsuch efforts are inconsistent with profit maximi-zat ion and the interests of shareholders , whomthey perceive to be the most important s take-holder .

This d ivergence in response has s t imula tedan impor tant debate regarding the re la t ionshipbetween CSR and f inancial performance. I t hasa l so ra i sed two re la ted ques t ions regard ing theprovision of CSR:1.Do socially responsible firms outperform orunderperform other companies that do notmeet the same social criteria?2. Precisely how much should a firm spendon CSR?

In exist ing stud ies of the relat ionship betw eenCSR and f inancia l per formance , rese arch ershave primari ly addressed the f i rst quest ion, andthe resul ts have been very mixed. Recent s tud-ies indicate no relat ionsh ip (McWilliams Sie-gel, 2000), a posi t ive relat ionsh ip (WaddockGrav es , 1 9 9 7), an d a neg a t i ve r e l a t i on sh ip117

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

2/12

118 Academy of Management Review January(Wright & Ferris, 1997).' This leav es man ag erswithout a clear direction regarding the desir-ability of investment in CSR. More important,the second question, which is of greater impor-tance to managers, has not been directly exam-ined in the academic literature.The purp ose of our study is to fill this void. Wepropose a methodology that enables managersto determine the appropriate level of CSR in-vestment, based on a theory of the firm perspec-tive.This perspective is based on the presump-tion that managers of publicly held firmsusual ly at tempt to maximize shareholderwealth, with a vigorous market for corporatecontrol as*the primary control me chanism(Jensen, 1988). Our framework applies generallytopublicly heldfirms but not necessarily toprivately held companies that may have alterna-tive objectives and are not subject to the marketfor corporate control. Based on this framework,we derive hypotheses regarding the demandand supply of CSR attributes across industries,firms, and products. Because these hypothesesand the conclusions we draw from them arerelevant to the extent that managers wish toenhance shareholder wealth, we are able to in-fer managerial implications.

THEORETIC L PERSPECTIVES ON CSRSeveral theoretical frameworks have beenused to examine CSR. Friedman (1970) assertsthat engaging in CSR is symptomatic of anagency problem or a conflict between the inter-ests of managers and shareholders. He arguesthat managers use CSR as a means to furthertheir own social, political, or career a gen das , atthe expense of shareholders. According to thisview, resources devoted to CSR would be morewisely spent, from a social perspective, on in-creasing firm efficiency. This theory has beentested empirically by Wright and Ferris (1997),who found that stock prices reacted negativelyto announcements of divestment of assets inSouth Africa, which they interpreted as beingconsistent with agency theory.The agency theory perspective h as bee n chal-lenged by other researchers, such as Preston

' For a review of theoretical and empirical studies of therelationship between corporate social performance and fi-nancial performance, see Griffin and Mahon (1997).

1978 and Carroll(1979),who outline a corporatesocial performance (CSP) framework. As expos-ited by Carroll (1979), this model includes thephilosophy of social responsiveness, the socialissues involved, and the social responsibilitycategories (one of which is economic responsi-bility). An em pirica l test of the CSP framework ispresented in the work of Waddock and Graves(1997), who report a positive association be-tween CSP and financial performance. The CSPmodel has much in common with the stake-holder perspective, which is the most widelyused theoretical framework.In a seminal paper on stakeholder theory.Freeman (1984) asserts that firms have relation-ships with many constituent groups and thatthese stakeholders both affect and are affectedby the actions of the firm. Stakeholder theory,which has emerged as the dominant paradigmin CSR, has evolved in several new and inter-esting ways. According to Donaldson and Pres-ton (1995), three aspect of this theorynorma-t ive, ins t rumental , and descript iveare m utually supportive. Jones and Wicks propose converging the social science (instrumental)and ethics (normative) components of stake-holder theory to arrive at a normative theorythat illustrates how mana gers can create mor-ally sound approaches to business and makethem work (1999: 206).The instrumental aspect and its relationshipto conventional theories in economics and cor-porate strategy have also received considerableattention in the literature. For instance, Jones(1995) developed a model that integrates eco-nomic theory and ethics. He concluded thatfirms conducting business with stakeholders onthe basis of trust and corporation have an incen-tive to demonstrate a sincere commitment toethical behavior. The ethical behavior of firmswill enable them to achieve a competitive ad-vanta ge, be cause they will develop lasting, pro-ductive relationships with these stakeholders.Russo and Fouts (1997) examined CSR from aresource-based view of the firm perspective.Using this framework, they a rgu e tha t CSP (spe-cifically, environmental performance) canconstitute a source of competitive advantage,especially in high-growth industries.Although these frameworks are useful, weoutline an alternative theoretical perspectivethat further develops instrumental aspects ofCSR. This framework allows us to develop a set

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

3/12

2001 McWilliams and Siegel of hypotheses regarding the determinants andconsequences of CSR. Addit ional ly, managerscan use this framework to determine preciselyhow much they should spend on CSR.

INVESTMENT IN CSR AT THE FIRM LEVELWe begin our analysis of CSR by relating it toa theory of the firm, in which it is assumed thatthe management of publicly held f i rms at temptsto max imiz e profits (Jensen, 1988). Ba sed on th isperspective, CSR can be viewed as a form ofinvestment . One way to assess investment inCSR is as a mechanism for product differentia-tion. In this context there ar e CSR reso urce san d outputs. A firm can create a certain levelof CSR by embodying its products with CSR

attributes (such as pesticide-free fruit) or byusing CSR-related resources in i ts productionprocess ( such as natural ly occurr ing insectinhibitors and organic fertilizers). As such, itseems natural to consider the nature of the mar-kets for CSR at tr ibutes and CSR-related re-sources. Our analysis of these markets is basedon a s imple supply and demand f ramework,which we outl ine below.

Demand for CSRWe hypothes ize that there are two majorsou rces of dem an d for CSR: (1) con sum er d e-ma nd a nd (2) dem an d from other stake holde rs,such as investors, employees, and the commu-nity. We begin by describing the nature of con-sumer demand for CSR.CSR investment may entai l embodying theproduct wi th socia l ly responsible a t t r ibutes ,such as pest icide-free or non-animal-tested in-gred ients. It may also involve the use of signa ls,such as the union label in clothing, that conveyto the consumer that the company is concerned

about certain social issues. This resul ts in thebelief that , by using these products, consumersare indirectly suppor t ing a cause and rewardingfirms that devote resources to CSR. Consumer-oriented CSR may also involve intangible at-tributes, such as a reputation for quality or reli-ability. Fombrun a nd Sha nley (1990) an d W eigeltan d Ca me rer (1988) hav e describe d how repu ta-t ion building is an integral component of strat-egy formulation. A rep utatio n for quality a ndreliability may be especially important for foodproducts. Thus, McDonald's employs the handi-

capped and suppor ts such organizat ions as theRonald McDonald House, establ ishing a reputa-tion for CSR. The presumption is that firms thatact ively support CSR are more rel iable and,therefore, their products are of higher quality.There is strong evidence that many (al thoughcer ta inly not a l l ) consumers value CSR at -tr ibutes. A growing nu mb er of com pan ies ha veincorporated CSR into their marketing strate-gies , because they wish to exploi t the appeal ofCSR to key segments of the market , such asbab y boomer or generat ion X shop pers. Weneed only look at the rapid growth of such so-cial ly respon sible c om pan ies a s Ben & Jerry's ,the Body Shop, and Hea lth Valley to confirm theimportance of CSR in marketing.CSR as a differentiation strategy Product (ser-

vice) differentiation is used to create new de-mand or to command a premium price for anexisting product (service). Firms that adopt adifferentiat ion strategy often pursue mult iplem ea ns of differentiation. An ex am ple is Ben &Jerry's, which differentiates its products by cre-at ing unique f lavors, using high-quali ty ingre-dients, suppo rt ing the local comm unity, an d pro-moting diversi ty in the work place. CSR may b e apopular means of achieving differentiat ion, be-cau se it a l lows man age rs to s imul taneously sa t -isfy personal interests and to achieve productdifferentiation. For example, Ben Cohen of Ben& Jerry's may h ave a perso nal , as w ell as aprofessional , commitment to diversi ty.

Differentiating through the use of CSR re-sources, such as recycled products or organicpest control , may also include investment in re-search and development (R&D). R&D investmentmay resul t in both CSR-related process andproduct innovations, which are each valued bysome consumers . For exam ple , the organic ,pest icide-free label simu ltaneou sly indica testhe use of organic methods, which const i tutes aprocess innovation by the taimei and the cre-ation of a new product category, which is a prod-uct innovation of thenatuial foods letailei. Iit henatural foods company is vert ical ly integrated,i t engages in both CSR-rela ted process andproduct innovation simultaneously. This exam-ple underscores the point that some consumerswant the goods they purchase to have certainsocial ly responsible at t r ibutes (product innova-tion), while some also value knowing that thegoods they purchase are produced in a social lyresponsible manner (process innovation).

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

4/12

120 Academy of Man agem ent fleview JanuaryAn addit ional example is New United MotorManufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI), the innovativejoint venture between Toyota and General Mo-tors, which wa s estab l ishe d in Fremont, Califor-nia, in 1984 to build sm all ca rs for both com pa-

nies . The NUMMI plant implemented many ofthe la tes t Japan ese lean manufactur ing meth-ods (process innovation) and produced the GeoPrism, the prototype for GM's new generation ofsm all cars (product innovation). These proc essesand the product innovations were the resul t ofR&D investmen t un dertak en by Gene ral Motors.Fur thermore, through i t s unique par tnershipwith the United Auto Workers (UAW), NUMMIal so implemented a number o f p rogress iveworkplace pract ices, such as a strong emphasison teamwork a nd em ployee empowerment . Con-s e q u e n t l y , s o m e c o n s u m e r s p e r c e i v e d t h a tNUMMI cars, such as the Geo Prism, were supe-rior to t radi t ional , American-m ade cars, in term sof quality and reliability. More important, manycustomers a l so bel ieved that by purchas ingthese cars, they were demonstrat ing their sup-port of progressive human resource manage-ment pract ices and the UAW.

Althoug h R&D ma y result in both proc ess an dproduct innovation, the vast majority of R&D isdevoted to product innovation (Link, 1982). Therole of CSR in product differentiation leads toour first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: There is a positive corre-lation between the level of productdifferentiation a proxy for which isthe ratio ofR Dexpenditures to sales)and the provision of CSR attributes.CSR and advertising For CSR differentiationto be successful , potential customers must befully aware of CSR characteristics; otherwise,they wil l purchase a similar product withoutsuch at tr ibutes. Some of these characterist ics

might not be evident to the buyer at first glance.Thus, advert ising plays an important role inra i s ing the awar ene ss of those individuals whoare interested in purchasing products with CSRat t r ibutes .The l i tera ture on adver t i s ing dis t inguishesbetween two types of goods: search and experi-en ce (N elson, 1970, 1974). Se arc h g oo ds a re prod -ucts whose at t r ibutes and quali ty can be deter-mined before purchase. For example, furni tureis usual ly considered to be a search good. Con-sumers search for the appropriate style and

quali ty. These at t r ibutes can be establ ished byexamining the product before purchase. Cloth-ing is another example of a search good. Withaccurate label ing as to the text i le content , theconsumer can establ ish the quali ty of the goodbefore pu rcha sing i t. For search goods, most ad-vertising will be limited to informing the con-sumer as to the avai labi l i ty of the product andits price.Experience goods are products that must beconsumed before their t rue value can be known.For example, food is an experience good. Theconsumer cannot determine from viewing theproduct how it will taste or whether it will besafe to consume. Advert ising for experiencegoods, therefore, will provide more information,usual ly tying the product to an es tabl i shedbrand name, such as Heinz. The associat ionwith brand name provides the consumer withinformation about the product through the rep-utat ion of the brand.As noted a bove , support of CSR creates a rep -utation that a firm is reliable and honest. Con-sumers typical ly assume that the products of areliable and honest firm will be of high quality.Adver t i s ing that provides informat ion aboutCSR at tr ibutes can b e used to build or susta in areputation for quality, reliability, or honestyall attributes that are important but difficult todetermine by search alone. For example, Heinzadvert ises i ts Starkist brand tuna as being dol-phin free. This provides the consumer with in-formation that the product has CSR at tr ibutesbut also that the company is trustworthy. Byimplication, the product will be of high quality.This type of advertising is used to foster productdifferentiation, allowing the firm to charge apremium pr ice .The l ink between advert ising and CSR leadsto our next two hypotheses.

Hypothesis 2:Because consumers relymore on firm reputation when pur-chasing experience goods than whenpurchasing search goods, CSR at-tributes are more likely to be associ-ated with experience than with searchgoods.Hypothesis 3:Because consumers mustbe made aware of the existence ofCSR attributes, there will be a p ositivecorrelation between the intensity of

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

5/12

2001 McWilhams and Siegel 121advertising in an industry a proxy forwhich is the ratio of advertising tosales) and the provision of CSR.

Additional determinants of consumer demand. We hypothesize that income is anotherde t e rminan t o f consumer demand for CSR.Whereas low-income shoppers general ly arequite price sensi t ive, aff luent consumers canmore easi ly pay a higher price for addit ionalCSR att r ibutes . Goods whose dem and increasesas income increases are cal led normal goods .We conjecture that CSR at tr ibutes are normalgoods, which m ea ns that gre ater levels of aff lu-ence , as reflected in higher disposable income,will result in greater demand for CSR.^

Hypothesis 4: Because CSR attributesare normal goods, there v/ill be a pos-itive correlation between consumerincome and the provision of CSR at-tributes.Other determinants of demand include tas tesand preferences, demographics, and the price ofsubst i tute products. Consumer taste and prefer-ences may be affected by mass media, and CSRhas become a hot topic in media circles. Jour-nalists often provide free publicity of a firm'scommitment or lack of commitment to CSR. The

media closely scrut inize some sectors, such asthe film industry an d professional sports . Celeb -rities and sports figures often use the media tohighlight their commitment to social responsi-bility. Journ alists a lso c losely follow the w ork ofsocial activists. Fedderson and Gilligan (1998)contend that media at tent ion devoted to socialact ivists provides the public with access to newinformat ion r egard ing soc i a l a t t r i bu t es andmethods of product ion. This f ree publ ic i ty ,whether pos i t ive or negat ive , helps heightenpublic awareness of CSR, reduces informationa s y m m e t r y , a n d , t h u s , i n f l u e n c e s d e m a n dfor CSR.

Demographics can also affect the demand forCSR. For instance, baby boomers have smallerfamil ies, greater household incomes, and more

soc i a l awareness t han prev ious genera t i ons .Thus ,they have the me ans to purch ase productswith CSR at tr ibutes and are increasingly l ikelyto make consumption choices based on socialgrounds. Savvy f irms wil l capital ize on thistrend.Because not al l consumers place a high valueon CSR at tr ibutes, the price of compe ting good swill still affect the demand for goods and ser-vices provided by firms that embrace CSR, ifthese competing goods are lower-cost al terna-t ives . Although most consumers might choose agood with CSR attributes if its price were equalto that of another good and many might choosea good with CSR attributes if its price were onlya l i t t le higher, some consumers wil l switchaway from the CSR good if there is a substantialprice difference. Therefore, there is a positiverelat ionship between the demand for goods withCSR at tr ibutes and the price of competing, orsubstitute, products (the higher the price of com-peting goods, the higher the demand for goodswith CSR at tr ibutes) . This lead s to an add it iona lhypothes is .

Hypothesis :There is a positive corre-lation between the price of substitutegoods and the demand for goods withCSR attributes.To summarize, we conjecture that the key de-terminants of the demand for a product withCSR at tr ibutes are the product 's price, advert is-ing to promote consumer awareness of CSR at-tr ibutes, the level of consumers ' disposable in-c o m e , c o n s u m e r s ' t a s t e s a n d p r e f e r e n c e s ,demographics, and the price of subst i tute prod-ucts .Table presents the determinants of demandand the predicted effect of each determinant on

TABLE 1Determinants of Consumer Demand forCSR Attributes

^ Some CSR attributes may even have the properties of a luxury good. That is, an incre ase in income may indu cegreater than proportional increases in the demand for CSRattr ibu tes (e.g., if income in cre ase s by 10 perce nt, the de-man d for CSR attributes w ill increase by m ore than 10 per-cent).

DeterminantPrice of goad with CSR attributesAdvertisingIncomeTastesDemographicsPrice of substitute goods

Hypothesized Effecton DemandNegativePositivePositiveIndeterminateIndeterminatePositive

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

6/12

122 Academy of Management Review Januarythe dem and for CSR at tr ibutes that is , whetherdemand increases or decreases when the de ter -minant increases (as designated by a posi t ive ornegative sign). As shown in the table, for somedeterminan ts , such as tas tes and demo graphics ,the effect is not easily predicted.Other stakeholders deman d. Employees areanother impor tant source of s takeholder de-ma nd for CSR. For examp le, they tend to sup portprogressive labor relations policies, safety, fi-nancial securi ty, and workplace amenit ies, suchas chi ld care. Workers search for s ignals thatmanagers are responding to causes they sup-port. Unions often play an important role in en-couraging f i rms to adopt these CSR policies.Note that un ions can also influence CSR policiesat nonunion firms in the same industry. This isan alo go us to the well-docum ented threat ef-fect of un ion s on non unio n wages (Freeman & edoff1983;Mills, 1994). For exa m ple , n onu nionfirms may adopt progressive work pract ices toavo id un ionism (Foulkes, 1980). Firms tha t sat-isfy employee demand for CSR may be re-warded with increased worker loyal ty, morale,an d pro du ctivity (Moskowitz, 1972; Pa rke t &Eibert, 1975). There is also som e evid enc e thatf i rms in industr ies with ski l led labor shortageshave used CSR as a means to recrui t and retainworkers (Siegel, 1999).Other stakeholder groups, including minori tyand community groups and local and state gov-ernments , can cont r ibute to the demand forproducts w ith CSR at t r ibutes a s well . For exam-ple , governments may encourage proact ive en-vironmental pract ices, and community groupsmay desire support for local social services,such as those provided by United Way. Thesegroups wil l then reward the f i rms by increasingtheir consumption of the firms' products. For in-stance, government contracts might require thatfirms undertake a certain level of CSR invest-ment , such as minori ty set-asides. Ult imately,these groups affect demand through consump-tion, either their own or that of the consumersthey influence. The characterist ics of demandfrom stakeholder groups other than consumerslead to the fol lowing hypotheses.

Hypothesis 6;There is a positive corre-lation between unionization of theworkforce an d the provision of CSR:that is in industries that are highly

unionized there will be more CSRprovided.Hypothesis 7: There is aposifive rela-tionship b etween the shortage ofskilled workers in an industry and theprovision of CSR: that is in industrieswith shortages o f skilled labor moreCSR will be provided.Hypothesis :There is a positive corre-lation between g overnment contractsand the provision of CSR.

The demand f rom al l s takeholders can besummed to arr ive at the overal l demand forproducts with CSR at t r ibutes. Recognizing thedem and for CSR, m ana gers can mak e decis ionson the number and level of CSR at t r ibutes andhow to produce them.

Supply of CSRAccording to the resource-based view of thefirm, resource s are al l ass ets , cap abil i t ies , or-gan izat iona l proce sses, firm a t t r ibutes, informa-tion, kno wled ge, etc. controlled by the firm (Bar-ney, 1991: 101). The reso urc e-b ase d view le ad sus to a supply-side perspect ive, which beginswith the realization that firms must devote re-sources to satisfy the demand for CSR. This in-dicates that we can modify the microeconomicconcepts of the production and cost functions toinclude CSR-related resources an d output . Thus,we assume that f i rms use CSR-related capi tal( land and equipment) , labor, materials , and pur-chased services to generate output .In Table 2 we desc ribe the inpu ts used ingenera t ing CSR at t r ibutes and the a t tendantcosts . As shown in the table, addi t ional capi talmight be required to generate CSR characteris-

t i c s . F o r e x a m p l e , p o l l u t i o n a b a t e m e n t t oachieve an envi ronmenta l s tandard beyond tha trequired by law wil l require the purchase ofaddit ional equipment . Similarly, off ice space,supplies, computers, telephones, and other com-municat ions equipment may be devoted to CSR.To the extent that addi t ional capi tal is required,capi tal costs wil l be higher.Although capital costs will be higher for firmsthat provide CSR, the costs will not increaseuniformly across firms. The use of capital in theprovision of CSR attributes may result in scale

economies , because capi ta l inves tment of ten

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

7/12

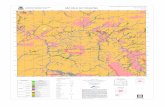

2001 cWilliams nd Siegel 123TABLEResourcesorInputs U sedin theProv isionofCSR

Resource or Input CSR Related Resource or Input Additional Resource or Input CostsCapi ta lMaterialsand servicesLabor

Special equipment, machinery,and real es tate devoted toCSRPurchaseof inputs from supplierswho aresocially resp onsibleProgressive human resourcemanagement pract icesandstaff to implement CSR policies

Higher capital expendituresHigher-cost materialsand services(intermediate goods)Higher wagesandbenefitsandadditional workerstoenhancesocial performance

entails substantial fixed costs. An example is asmokestack scrubber. The cost of a scrubber isfixed, once a particular piece of equipment isinstalled. The cost of the scrubber will be amor-tized over the number of units of output the firmproduces. The higher the level of output, thelower the per unit cost of the scrubber, resultingin an economy of scale.

Intermediate materials and services may alsobe related to the provision of CSR. For example,the Body Shop purchases special ingredientsand formulas that have not been animal tested,Ben Jerry's has a stated policy of purchasingdairy products from local Vermont farmers, andWal-Mart advertises that its products are madein America. Locally produced goods and ser-vices may be more costly than those importedfrom other states and countries, resulting inhigher costs for these socially responsible firms.There might be scale economies related to thesecosts, however, because of the ability of largefirms such as Wal-Mart to obtain quantity dis-counts on CSR-related intermediate goods andmaterials.Firms may hire additional staff to advanceCSR through affirmative action, improved la-bor relations, and community outreach. Exist-ing employees also may be asked to promotethese efforts. At the 1997 Philadelphia sum-mit on voluntarism, sponsored by PresidentClinton and Colin Powell, numerous compa-nies pledged to dedicate additional humanresources to CSR activities. Many large firms

Therearelimitstoscale econom ies. Afteralleconomiesof scaleare exhausted, average cost will climb with addi-tional output. This diseconomyofscaleisusually associatedwith physical capital constraintsorwith mana geria l limita-t ions. Managerial limitations might, for example, resultinless flexibility inresponding to social issues in very largefirms.

have entire departments devoted to CSR con-cerns. The costs of personnel devoted to CSRand additional CSR-related benefits providedto workers increase the overall labor costs offirms. However, human resources may alsogenerate economies of scale, because theyrepresent a fixed cost that can be amortizedover numerous units of output.

When scale economies exist, large firms willhave lower ver ge costs for providing CSRattributes than small firms. This implies thatthere may be some differences in the return tofirms within industries. Therefore, within in-dustries in which CSR attributes are provided(because the product/service can be differen-tiated), larger firms will provide more CSRattributes.We conjecture that there are economies ofscope in the provision of CSR, or cost savingsthat arise from the joint production of CSRcharacteristics for several related products. Alarge, diversified firm can spread the cost ofCSR provision over many different productsand services. For example, the goodwill gen-erated from firm-level CSR-related advertisingcan be leveraged across a variety of the firm'sbrands. When scope economies exist, more di-versified firms will have lower average costsof providing CSR attributes than firms focus-ing on one particular industry. Thus, we ex-pect a positive relationship between firm di-versification and the provision of CSRattributes, all else being equal.

Our discussion of the costs of providing CSRattributes has revealed that embodying prod-ucts with CSR attributes requires the use of ad-ditionql resources, which results in higher costs.When considering the appropriate level of CSRcharacteristics, managers must make criticaldecisions regarding the optimal use of inputs

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

8/12

124 Academy of Management Review nu rythat generate these attributes.^ Thus, a firm'scost of producing CSR attributes is positivelyrelated to the number of these characterist ics.The cost function has the usual properties. First,it is mono tonical ly in creas ing in CSR at tr ibute s;that is , i t costs more to gene rate add it ional char-acteristics. Second, at some point there are in-creasing incremental costs of providing CSR,which resul t s in a s tandard upward-s lopingsupply curve for CSR attributes. The nature ofthe supply of CSR attributes leads to the follow-ing hypotheses regarding the provision of CSRacross industr ies and f irms.

Hypothesis 9: Firms that provide CSRattributes will have higher costs thanfirms in the same industry that do notprovide CSR attributes.Hypothesis 10: The presence of scaleeconomies in the provision of CSR at-tributes results in a positive correla-tion between firm size and the provi-sion of CSR attributes.Hypothesis 11:The presence of scopeeconomies in the provision of CSR at-tributes results in a positive correla-tion between the level of diversifica-tion of a firm and the provision of CSRattributes.

A cave at to Hypothesis 9 must be mentioned .As noted earl ier , a f i rm may fundamental lychange i ts production process in response to aCSR concern, such as conservation. Thus, it isconce ivable that a CSR -oriented process innova-tion could result in the creation of a CSR char-acteristic at the same or even a lower level ofcost. Examples of this, however, are difficult tofind, whereas examples of higher costs for CSRproducts abound. For instance, a t r ip to the su-permarket reveals that goods with social char-acteristics (e.g., organic produce) typically costmore than similar goods without social charac-teristics (e.g., nonorganic produce).

In our model we assum e that the two firms use the s am eproduction technology. This does not apply to a situation inwhich firms adjust their production processes to reflect CSRconcerns.

Determ ining the ppropriate Level ofCSR InvestmentThe supply and demand framework impliesthat there is some optimal level of CSR at-tributes for firms to provide, depending on the

demand for these characterist ics and the costsof generat ing them. Companies that do not sup-ply CSR at tr ibutes have lower costs, but theyface a different (lower at every price) demandcurve th an firms tha t do provide the m. 'Firmsthat supply CSR will have higher costs for everylevel of output th an firms th at do not supp ly CSRand produce s imi lar goods .Those consumers whovalue CSR are willing topay a higher price for a product with an add itionalsocial characteristic th an for an identical productwithout this characteristic. This result is contin-gent on consu mers be ing aw are of the existenceothe CSR attribute. If consumers are not aware ofthis additiona l social feature, they will choose thelower-priced product. Thus, advertising plays animportant role in determ ining th e optimal level ofCSR attributes or outputs provided. Advertisingalso helps raise awa rene ss regarding f irms' useoCSR inputs, which may be of interest to severalstakeholder groups.The provision of CSR attributes will depe nd aswell on certain ch aracteristics of the market, su cha s the deg ree to which firms ca n differentiate theirproducts and the industry life cycle. Thus, one islikely to find CSR attributes in industries withhighly differentiated products, such as food, cos-metics, Pharmaceuticals, financial services, andautomobiles. In the embryonic and growth stagesof the industry life cycle, we expect that there islittle product differentiation, as firms focus on per-fecting the production proce ss and satisfying rap -idly growing dem and . As growth slows, an d e spe-cially a s the indu stry ma tures, there is likely to bea great deal of differentiation. For example, in theice cream industry, simple flavors, such as va-nilla, dominated in the embryonic and growthstages. As tastes and markets became more so-phisticated, more flavors were introduced. In thecurrent maturity phase there is substantial prod-uct differentiation (flavors, fat content, modes ofdelivery, an d so forth). Ben Jerry's ha s capital-ized on the poss ibility of differentiation throu ghflavors and CSR attributes.Demographic and technological changes alsocan stimulate demand for CSR attributes. Therapid rise in the number of working women hasresulted in an increase in the demand for corpo-

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

9/12

2001 cWilliams and Siegel 125rate-supplied day care, flexible work schedules,an d telecomm uting. On the supply side, the riseothe internet has made it much easier for firms totarget consumers who have social goals. This isevident in the substantial growth in the numberoweb sites devoted to CSR activity. These havedram atically redu ced th e cost of transmitting CSRinformation to consumers and other interestedstakeholders. Examples include the Toyota andHonda web sites, which are devoted to informa-tion about their electric cars. On the d em and side,the internet makes it easier for groups who sharecommon so cial goals to exc han ge information. Forexam ple, there are virtual com mun ities (geocities)for those outside the mainstream of society.

M N GERI L IMPLIC TIONSOur analysis reveals that there is some level ofCSR that will maximize profits while satisfyingthe demand for CSR from multiple stakeholders.The ideal level of CSR can be de termined by cost-benefit analysis. To maximize profit , the firmshould offer precisely that level of CSR for whichthe increased revenue (from increased demand)equals the higher cost (of using resources to pro-vide CSR). By doing so, the firm meets the de-mands of relevant stakeholdersboth those thatdem and CSR (consumers, emp loyees, community)

an d those that own the firm (shareholders).On the demand s ide , managers wi l l have toevaluate the possibility of product/service dif-ferentiation. Where there is li t t le ability to dif-ferent iate the product or service, demand maynot increase with the provision of CSR. On thesupply s ide , ma nag ers wi l l hav e to evalu ate theresource costs of promoting CSR while beingcognizant of the possibi l i ty that there may bescale and/or scope economies associa ted wi ththe provision of CSR. In sum, managers shouldtreat decisions regarding CSR precisely as theytreat al l investment decisions.

DISCUSSIONIn this s tudy we at tempt to answer a quest ionthat has rece ived inadequate a t tent ion in theCSR l i terature: Precisely how much should afirm spend on CSR? We addressed this issueusing a supply and demand theory of the f i rmframework an d found tha t there is a level of CSRinvestment that maximizes profi t , while alsosat isfying stakeholder demand for CSR. This

level of investment can be determined throughcos t -benef i t analys i s . Managers can use ourframework to ma ke decisions reg ardin g CSR in-ves tment by employing the same analyt ica ltools used to make other investment decisions.We hav e also developed several hypotheses re-garding CSR activityfor example, the provisionof CSR will depen d on R&D spending, adve rtisingintensity, the extent of product differentiation, thepercentage of government sales, consumer in-come, the tightness of the labor market, and thestage of the industry life cycle. Additionally,the likelihood of economies of scale and scope inthe provision of CSR imp lies that lar ge, diversifiedcom panie s will be m ore active in this aren a. Mostimportant , our model indicates that al thoughfirms providing CSR will have higher costs than

firms not providing CSR, they will each have thesame rate of profit.To assess the impact of CSR on profitability,we present the fol lowing simple example. As-sume there are two f i rms that produce ident icalgoods, except one company adds a social char-acteristic to its product. Invoking the theory ofthe f i rm, we assume that each f i rm makes opt i-mal choices, which me ans tha t each produce s a ta profit-maximizing level of output. It can beshown that , in equil ibrium, both wil l be equal lyprofitable. The firm that produces a CSR at-

t r ibute wil l have higher costs but also higherrevenues, whereas the f i rm that produces noCSR at t r ibutes wil l have lower costs but alsolower revenues. Any other resul tfor instance,one firm earning a higher rate of returnwouldca us e the other firm to switch product s t rate gies.Note that our conclusion is based on the as-sumption that there are no entry barr iers asso-ciated with providing the social characterist ic .Our conclusion that profi ts wil l be equal mayexplain why there is inconsistent evidence re-garding the relat ionship between CSR provisionand firm performance. According to our argu-men t, inequilibrium there should be no relat ion-ship .CSR at t r ibutes ar e l ike any other at t r ibu tesa firm offers. The firm chooses the level of thea t t r i bu t e t ha t max imizes f i rm pe r fo rmance ,given the demand for the at t r ibute and the costof providing the attribute, subject to the caveatthat this holds t rue to the extent that managersare a t tempt ing to maximize shareholder weal th .From this we predict that there w ill genera l ly bea neutral relat ionship between CSR act ivi ty andfirm financial performance.

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

10/12

126 Academy o/ Management Review JanuaryIt appears that the lack of consistency in em-pirical studies of CSR is due to a lack of theorylinking CSR to market forces. Our supply anddem and framework fills this void, allowing us topredict that the provision of CSR will vary

across industries, products, and firms. There-fore, those empirical studies in which research-ers have not controlled for all the firm or indus-try characteristics we have identified here areprobably misspecified.Unfortunately, many of our hypotheses are dif-ficult to test empirically, given the lack of dataon the demand for and supply of CSR. We pro-pose that the government or management re-searchers working with government supportsystematically collect information on the socialcharacteristics of products and CSR activity atthe firm and industry level.^ This would enableresearchers to test our hypotheses and also al-low them to conduct an hedonic an aly sis(Griliches, 1990) of CSR to determine exactlyhow much consumers and other stakeholdersare willing to pay for CSR attributes.

REFERENCESBarney, J. 1991. Firm resour ces an d su sta ine d comp etitiveadvan tage .Journalo/ Management. 17: 99-120.Carroll, A. 1979. A three dim ensi ona l m odel of corporate per-

formance. Academy oi Management Review 4:497-505.Don aldson, T., & Pre ston, L. 1995. The sta keh olde r theory ofthe corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications.Academy of Managem ent Review 20: 65-91.Fedderson, T., Gilligan, T.1998.Saints and markets.Work-ing paper, Northwestern University, Evanston IL.Fombrun, C & Sha nley, M. 1990. Wh at's in a nam e? Repu-tat ion bui ld ing and corporate s t rategy. Academy ofManagement Journal 33: 233-258.Foulkes, F. K. 1980. Personnel policies in large nonunioncompanies. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.Freeman, R. 1984. Strategic managemen t: A stakeholder

perspective. Englewood C liffs, NJ: Prentice-H all.Freeman, R. B., Medoff J.L. 1983.What dounions do?N ewYork: Basic Books.Friedman, M. 1970. The social responsibility of business is toincrease its profits. New York Times September 13:122-126.

' The firm of Kinder, Lydenberg, and Domini provides a rating of selected publicly held firms based on their socialperformance in eight categories, including community, di-versity, employee relations, product, environment. South Af-rica, military, and nuclear power. This rating has been usedas a proxy for the supply of CSR.

Griffin, J., & Ma hon, J. F. 1997. The c orp ora te soc ial perfor-mance and corporate f inancial performance debate:Twenty-five years of incomparable research. Businessand Society, 36: 5-31.Griliches, Z. 1990. Hedonic price index es an d the mea surem entof capital and productivity: Some historical reflections. In

E. Bemdt J. Triplett (Eds.),Fifty years of economic mea-surement: The jubilee of the conference on research inincome and wealth 185-202. Chicago: University of Chi-cago Press.Jensen, M. 1988. Takeovers: Their cau ses and conseq uence s.Journal of Econom ic Perspectives 2 1): 21-44.Jones, T. 1995. Instr um enta l sta keh olde r theory: A synthe sisof ethics and economics. Academy of ManagementBeview 20: 404-437 .Jones, T., & Wicks, A. 1999. Con verge nt stak ehol der theory.Academy of Managem ent Review 24: 206-221.Link, A. 1982. A disaggregated analysis of industrial R&D:

Product versus process innovation. In D. Sahal (Ed.), Th etransfer and utilization of technical knowledge 4563.Lexington, MA: Heath.McW illiams, A., Siegel,D. 2000. Corporate social responsibil-ity and financial performance: Correlation or misspecifi-cation?Strategic ManagementJournal 21:603-609.Mills, D. Q. 1994. Labor-managemen t relations. New York:McGraw-Hill.Mitchell, R., Agle, B., & Wood, D. 1997. Toward a theory ofstakeholder identification and salience : Defining theprinciple of who and what really counts. Academy ofManagement Review 22: 853-886.Moskowitz, M. 1972. Cho osing socially re spo nsibl e sto cks.Business &Society Review, 1: 71-75.Nelson, P. 1970. Information and consumer behavior.Journalof Political Econom y 78: 311-329.Nelson, P. 1974. Adv ertising a s information, /ournaiof Polit-ical Economy 81:729-754.Parket, 1., Eibert, H. 1975. Social r espon sibility; t he unde r-lying factors.Business Horizons 18 4): 5-10.Preston, L. Ed.). 1978. Research in corporate social perfor-mance and policy vol. 1. Gre enw ich, CT: JAI Press.Russo, M. V., & Fouts, P. A. 1997. A resou rce- base d pers pec -tive on corporate environmental performance and prof-itability. Academy of Management Journal 40: 534-559.Siegel,D.1999.SMU biased technologicalchange:Evidence fromafirm levelsurvey. Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn Institute Press.Wadd ock, S., & Gra ves, S. 1997. The corp orate social perfor-mancefinancial performance link. Strategic Manage-mentJournal 18:303-319.Weige lt, K., & Cam erer, C . 1988. Rep utation an d corpo rates trategy:Areview of recent theory and a pplication. Stra-tegic Management Journal 9: 443-454.Wright, P., & Ferris, S. 1997. Agency conflict an d corpo ratestrategy: The effect of divestment on corporate value.Strategic management Journal 18: 77-83.

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

11/12

2001 cWilliams and Siegel 127

b agail McW illiams i s p ro fes so r an d h ead o f t h e M an ag er i a l S tu d i es Dep ar tmen tUnivers i ty o f I l l ino is a t Chicago . She received her Ph .D. in economics f rom The OhioState Univers i ty . Her research in teres ts include market s t ructure and f i rm perfor-ma n ce s t r a t eg i c h u m an r eso u rce ma n ag e m en t g en d er i s su es i n wo rk er mo b i l it y an dcorporate social responsib i l i ty .Donald Siegel i s p rofessor o f indust r ia l economics at the Not t ingham Univers i tyBu siness School in the Uni ted Kingdom. He received h is Ph .D. in bu sin ess econom icsfrom Colum bia Univers i ty . His rese arc h in teres ts include product iv i ty ana lysi s theeco n o mic an d man ag er i a l imp l i ca t i o n s o f t ech n o lo g i ca l ch an g e u n iv e r s i t y t ech n o l -o g y t r an s fe r sc i en ce p a rk s an d co rp o ra t e so c i a l re sp o n s ib i l i ty .

-

8/12/2019 CSR ellen

12/12