Crosstalk July 2006 - ERIC · LONG BEACH, CALIFORNIA T HERE ARE TWO THINGS you need to know about...

Transcript of Crosstalk July 2006 - ERIC · LONG BEACH, CALIFORNIA T HERE ARE TWO THINGS you need to know about...

nation watched the ultimate sports dramareach its climax.

“Northeastern University,” advertisedthe billboard.

“It was fortuitous timing,” said North-eastern’s Brian Kenny, with understate-

ment uncharacteristic of a university vicepresident of marketing.

In addition to being a great stroke ofluck, Northeastern’s billboard inside Fen-way Park was part of an aggressive andextraordinarily successful marketing cam-paign by a school whose very survival had

Vol. 14 No. 3 Summer 2006 Published by The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education

The M Word“Marketing” has changed from a dirty wordto a buzzword in higher educationBy Jon Marcus

BOSTON

WITH EVERY HIT that echoedfrom the hallowed walls ofFenway Park, every roar from

the hopeful sell-out crowds of fans whohad been praying for this 2004 WorldSeries, seasons of heartbreak inched closerto an end. Success hung in the brisk Octo-ber air. Respect was finally at hand. Withevery pitch, a longtime Boston institutiongrew nearer to reversing years of despair.

And it wasn’t just the Red Sox.There, on Fenway’s right-field grand-

stands, between the ads for soft drinks,beer and life insurance, hung a simple redand white billboard. It had been almost awhim, an outgrowth of some research thatsuggested baseball fans aspired to enrolltheir kids in college. At the beginning ofthe season, when the arrangements hadbeen made, no rational New Englanderwould have believed this was the year itwould be beamed to tens of millions as the continued on page 14

In This Issue

By Robert A. Jones

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

MONTY NEILL, the executivedirector of FairTest, stood in anempty room on an empty floor

of a vintage office building near Harvard

University. He motioned to a corner. That’swhere a FairTest researcher once worked.And over there, along the wall, stood a rowof file cabinets packed with research mate-rials going back 20 years.

Robert Schaeffer, one of FairTest’sfounders and still its public educationdirector, stood next to Neill, looking a bituneasy. Even now, he said, it can feel continued on page 5

embarrassing to talk publiclyabout the near collapse of theorganization that has consumedmost of his life’s work. FairTest,he said, has played its role as gad-fly in the world of standardizedtesting for so long that manyassumed it could not stumble andfall.

But stumble it certainly did.Over the past two years FairTesthas progressively retrenched as itsfinancial backers, mostly founda-tions, withdrew their support.Last October, the situation be-came so dire that the Board ofDirectors briefly considered shut-ting its doors. Ultimately theydecided to hunker down instead,leaving only Neill and Schaefferon the payroll and shrinking theoffice space to a fraction of its former size.

Now, nine months later, FairTest’s crisishas eased somewhat. Revenues from theorganization’s website increased in thespring, thanks largely to the group’s role inuncovering the SAT scoring scandal at

been threatened, only years before, by asharp drop in enrollment. It was also thevanguard of a new wave of marketing byuniversities and colleges—no longer justthe ones that might be vulnerable to enroll-ment or financial problems, but also

N A T I O N A L

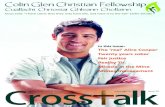

Northeastern President Richard Freeland welcomes fans to NU Family Day atFenway Park in Boston. This is part of Northeastern’s marketing campaign.

DAVID HOROWITZ’ claims thatcollege and university faculties

are dominated by professors with leftwing views have stirred up controver-sies in several states. (See page 8.)

FairTest’s longtime adversary, the CollegeEntrance Examination Board. Visits to thewebsite increased dramatically along withsome private donations.

The notion of FairTest being saved by

MJ

MA

LON

EY,B

LAC

KSTA

R,FO

RC

RO

SSTALK

Like consumer productmanufacturers, schoolsincluding NortheasternUniversity and DePaulnow conduct marketinganalyses before adding

new programs.

healthy institutions that had long lookeddown their noses at such things.

“I’ve seen ‘marketing’ change from adirty word to a buzzword,” said MichaelNorris, director of communications and

From its start in 1986,FairTest has played the

role of outsider in the clubby, oftenopaque world of

standardized testing.

A Contrarian View ofthe Testing IndustryFairTest argues that standardized testsare a poor predictor of student success

Monty Neill is executive director of FairTest,persistent critics of standardized testing,especially the SAT.

DE

NN

ISB

RA

CK

,BLA

CK

STAR

,FOR

CR

OSSTA

LK

MJ

MA

LON

EY,B

LAC

KSTA

R,FO

RC

RO

SSTALK

Page 2 CROSSTALK

Board of DirectorsJames B. Hunt Jr.

CHAIRMAN

Garrey CarruthersVICE CHAIRMAN

Patrick M. CallanPRESIDENT

Robert H. AtwellRamon C. CortinesDolores E. Cross

Alfredo G. de los Santos Jr.Virginia B. EdwardsJames M. FurmanMatthew H. KisberCharles E.M. KolbJoanne C. Kozberg

Arturo MadridRobert H. McCabe

Jack ScottThomas J. Tierney

Uri TreismanDeborah WadsworthHarold M. Williams

Virginia B. SmithFOUNDING DIRECTOR

National CrossTalk is a publication of the National Centerfor Public Policy and Higher Education. The National

Center promotes public policies that enhanceopportunities for quality education and training beyond

high school. The National Center is an independent,nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that receives core

support from national philanthropic organizations,including the Pew Charitable Trusts, the Atlantic

Philanthropies and the Ford Foundation.

The primary purpose of National CrossTalk is to stimulateinformed discussion and debate of higher education issues.

The publication’s articles and opinion pieces are writtenindependently of the National Center’s policy positions

and those of its board members.

Subscriptions to National CrossTalk are free and can beobtained by writing a letter or sending a fax or e-mail to

the San Jose address listed below.

Higher Education Policy InstituteThe National Center for Public Policy and Higher

Education152 North Third Street, Suite 705, San Jose, CA 95112.

Phone: (408) 271-2699; Fax: (408) 271-2697; E-mailaddress: [email protected]; Website:

www.highereducation.org.

Patrick M. CallanPresident

Joni E. FinneyVice President

William TrombleySenior Editor

Daphne BorromeoCoordinator for Media Relations

Jill A. De MariaDirector of Publications and Web Production

Holly EarlywineAccounting Manager

Jonathan E. FelderPolicy Analyst

Deborah FranklePolicy Analyst

Young KimPolicy Analyst

Valerie LucasAssistant to the Vice President

Gail MooreDirector of Administration and Special Projects

Mikyung RyuSenior Policy Analyst

Todd SalloEditing and Production, National CrossTalk

Noreen SavelleExecutive Assistant

Michael UsdanSenior Fellow

Shawn R. WhitemanAssistant Director of Administration and Assistant

Production Manager

NEWS FROM THE CENTER

DAVID S. SPENCE, president of theSouthern Regional Education Board andformer executive vice chancellor of the

California State University system, has beenawarded the Virginia B. Smith Innovative Lea-dership award for 2006.

As Cal State vice chancellor, Spence led the ef-fort to develop a voluntary early assessment pro-gram (EAP) that enables high school juniors toidentify weaknesses in their college preparationwork in time to correct the deficiencies in their se-nior year.

“The EAP has made college readiness stan-dards more concrete for schools, teachers and,most importantly, students,” said Patrick M.Callan, president of the National Center for PublicPolicy and Higher Education. “Through his workwith the program, David Spence has helped toconnect these standards to the high school curricu-lum.”

The National Center and the Council for Adultand Experiential Learning jointly administer theaward, which is named for Virginia B. Smith,President Emerita of Vassar College and longtimesupporter of innovation in higher education. u

Virginia B. Smith Award

PREPARATION of the “Measuring Up” reports pub-lished by the National Center for Public Policy andHigher Education has been guided by a team of higher

education policy experts, shown at a recent meeting of the advi-sory committee in San Jose, California.

Back row (left to right): Sue Hodges Moore, vice presidentfor planning, policy and budget, Northern Kentucky University;Peter T. Ewell, vice president, National Center for HigherEducation Management Systems; Alan Wagner, professor andchair, Department of Educational Administration and PolicyStudies, State University of New York at Albany; Richard D.Wagner, retired executive director, Illinois Board of HigherEducation; Emerson J. Elliott, retired commissioner, National

Center for Education Statistics; and Jane Wellman, senior associ-ate, Institute for Higher Education Policy.

Front Row (left to right): Margaret A. Miller, director, Centerfor the Study of Higher Education, Curry School of Education,University of Virginia; Dennis P. Jones, president, NationalCenter for Higher Education Management Systems; David W.Breneman, University Professor and Dean, Curry School ofEducation, University of Virginia; and Gordon K. Davies, direc-tor, National Collaborative for Postsecondary Education Policy.

Professor Wagner is a consultant on the project but not amember of the advisory committee. Another consultant, WilliamP. Doyle, assistant professor at Vanderbilt University, was notpresent when the photograph was taken. u

Measuring Up 2006 will be Released September 7

RO

DSE

AR

CE

YFO

RC

RO

SSTALK

AX

EL

KO

ESTE

RFO

RC

RO

SSTALK

Page 3CROSSTALK

Charles B. ReedCal State chancellor strives to promotequality and diversity in the nation’s largestfour-year college systemBy Kathy Witkowsky

LONG BEACH, CALIFORNIA

THERE ARE TWO THINGS youneed to know about Charlie Reed,chancellor of the massive Cali-

fornia State University and one of thenation’s most respected higher educationadministrators. For eight years now, Reedhas headed the largest four-year system inthe country, using his unique blend of polit-ical instincts, competitive drive and direct,plain-spoken manner to keep Cal State“on the move,” as he likes to put it.

Number one, Charles Bass Reed lovesto work. “I don’t think anyone can out-work me,” he said during a recent inter-view. This is not a boast so much as a state-ment of fact, one that comes up in nearlyevery conversation you have about Reed.“His biggest strength is his dedication tothe system, his willingness to work unbe-lievable hours, and his tremendous ener-gy,” said Murray Galinson, immediate pastchair of the Cal State Board of Trustees.

Even non-fans—and there aren’tmany—concede that point. As president ofthe Cal State Faculty Association, the fac-ulty union that has been in protracted andcontentious negotiations with the adminis-tration for more than a year, John Travishas been one of Reed’s harshest and mostvocal critics. Nonetheless, Travis acknowl-edged, “Charlie has worked very hard topromote his vision. And I will give himcredit for that.”

Charlie Reed’s vision, like the man him-self, is at once both extraordinarily straight-forward and extremely ambitious. Hewants his 23-campus, 44,000-employee sys-tem to serve more students, because edu-cation is their ticket to better jobs and bet-ter health, which in turn will create a bettereconomy. “That’s what universities are sup-posed to do, is improve the quality of life of

Chancellor Charles B. Reed addresses the congregation at Oakland’s Allen TempleBaptist Church, part of Cal State’s extensive outreach effort.

PHO

TOS

BY

RO

DSE

AR

CE

YFO

RC

RO

SSTALK

its citizens,” said Reed.And to do that, Reed says, Cal State

must reach beyond its 405,000 students andinto the state’s K–12 classrooms, wheremany students aren’t getting the educationthey need to succeed in college. More thanhalf of all incoming Cal State freshmenneed remedial coursework in English ormath, or both.

Because Cal State prepares 55 to 60percent of the state’s public school teach-ers, it is in a position to improve that dis-mal remedial statistic. That is why Reedhas been so focused on improving andexpanding the institution’s teacher trainingprograms, which have grown 65 percentsince he arrived. Cal State now graduates15,000 teachers a year, but the state stillfaces a critical shortage of math and sci-ence teachers. So Cal State has undertakena $2 million, five-year effort to double thenumber of math and science teachers itprepares, from 800 to 1,600.

But numbers aren’t enough, said Reed:Cal State must also improve the quality ofteaching. It has begun to offer a free 80-hour retraining program for math andEnglish teachers. Next year, it will comparereading scores of Cal State-trained teacherclassrooms to those of teachers trainedelsewhere.

Also under Reed’s leadership, Cal Statehas garnered national attention for innova-tive programs designed to help studentsprepare for college. One of the simplest isalso among the best known: Cal State hasdistributed more than 70,000 copies of itsfree “Steps to College” poster, a Reedbrainchild that spells out what middleschool and high school students need to doto get there. It is available in five lan-guages.

Meanwhile, more than 150,000 highschool juniors have used Cal State’s volun-tary early assessment program, or EAP,

which allows them to take an augmentedversion of a mandatory 11th-grade stan-dardized exam so they can find out ifthey’re ready for college-level work; if not,they still have a chance to catch up duringtheir senior year. Should they choose, theycan do so online, through tutorial websitesCal State has developed.

“He’s one of the most important playersin K–12 education,” said Jack O’Connell,California state superintendent of publicinstruction, who refers to himself as chair-man of the Charlie Reed fan club. “He’shelped us break down the walls of all thesegments of education.”

Reed is trying to bust through racialand ethnic barriers as well. Fifty-five per-cent of Cal State students are minorities.That sounds like a lot, but the figure is stillfar less than it should be, said Reed, whowants the Cal State population to betterreflect the population in the state’s highschools, where more than two-thirds of stu-dents are minorities. So this year, Reed hasstepped up the outreach, going beyond thepublic schools and into the communities ofunderrepresented students.

Top administrators from Cal State,including university presidents and Reedhimself, have made presentations duringSunday services at 19 African Americanchurches in Los Angeles and the SanFrancisco Bay area to persuade potentialstudents and their families that college isan important goal. Just seven percent ofCal State students are African American;only one third of these are male.

More than 30,000 people attendedthese two so-called Super Sunday events;afterwards, some people stood in line fornearly half an hour to collect the materialsthat Cal State was handing out. The enthu-siastic response thrilled Reed. “If you’venever had a grandparent or parent, brotheror sister, who’s been to a university, whatthe hell do you think you’d know aboutcollege?” he said. “They were starved forinformation.”

The events garnered praise from thechurch pastors and congregation members.And Assemblyman Mervyn Dymally, whohas been involved in politics for nearly halfa century and currently chairs the Califor-

nia Legislative Black Caucus, called them,“an act of political genius.”

“That was a coup,” said Dymally. “I’venever known a white college administratorto get into a black church.”

Administrators from Cal State havealso met with Vietnamese American, Na-tive American and Hispanic communityleaders. Cal State plans to continue theoutreach, which will include two moreSuper Sundays next year.

In the meantime, Reed said, Cal Statemust also continue to improve articulationagreements with community colleges, thegateway for 55 percent of Cal State under-

graduates. It must make better use of tech-nology to help reduce the time it takes forstudents to graduate—currently about fiveand a half years for first-time freshmen—so it can accommodate more students. Itmust partner with industry to ensure that itis teaching the right job skills and providinginternships.

And, armed with a recent economicimpact study that quantifies the jobs andthe money Cal State generates for the state(82,000 annual graduates, 1.7 million alum-ni, earning $89 billion annually), it mustconvince Californians of its value so it canraise more money from the private sector.The system still has not recovered frommore than $500 million in cuts it sufferedduring California’s recent budget crisis.

The success of the institution rides onits ability to make progress in all thoseareas, Reed said, because they’re inextrica-bly intertwined. It’s a tough juggling act,but Reed thrives on the challenge. “I like

Charlie Reed’s visionfor the California State

University system, like the man himself,

is at once bothextraordinarily

straightforward andextremely ambitious.

California Assemblyman Mervyn Dymally called Reed’s church appearance “anact of political genius.” continued next page

Page 4 CROSSTALK

keeping all those balls in the air,” he said.That he is able to do so makes him a

rare talent, said David Ward, president ofthe American Council on Education. “He’swithout question one of the big thinkersabout big solutions,” said Ward. “As sys-tem president, he really does look at thingsfrom the broad social perspective ratherthan an institutional or campus perspec-tive. And he does that very, very well.”

Reed is up at five o’clock and at hisLong Beach office by 6:30, where he pre-pares two pots of coffee for his staff beforehe attacks his lengthy “working list” of pri-orities, which is updated every couple ofmonths, and which he has whittled down

from 56 when he first took the job to amere 30 today. In his eight years as chan-cellor, Reed has never missed a singleworkday; what’s more, he routinely worksweekends, putting in three weeks straightbefore taking a day off.

On his office shelves, surrounded byphotographs and autographed sports para-phernalia, is a framed motto that sums upReed’s approach to life: “You work as hardas you can all day, and if you make a mis-take, you fix it. That’s all you can do.” Now64, Reed has lived by that creed ever sincehe was a child growing up in the tiny coal

from preceding page mining town of Waynesburg, Pennsylvania,where he was the oldest of eight siblings,and where he met his wife of 42 years,Catherine.

She first noticed him when they wereboth in junior high. Reed had a job at aproduce stand, and she and her friendswould see him as they drove past on theirway to the swimming pool. “One day I gotmy mother to stop at the fruit market and Iasked why he didn’t want to go to theswimming pool,” recalled Catherine Reed.“And he said he really liked to work, andthat was more fun for him than going tothe swimming pool.”

As much as Charlie Reed loves towork, he hates to lose. And that’s the sec-ond thing you need to know about him.“He will never lose,” said Catherine Reed.“It might appear that he loses, but he’ll beback.” And back. And back. And back.Until eventually, she said, he’ll win.

Reed developed his competitive in-stincts on the gridiron, where he playedboth offense and defense. First he wasquarterback and linebacker for his highschool football team, which he led to thestate finals. Then he played halfback anddefensive cornerback for George Wash-ington University, which he attended on afootball scholarship, majoring in healthand physical education, and where he laterearned his master’s degree in secondaryeducation and an Ed.D. in teacher educa-tion.

Reed honed his political skills as educa-tion policy coordinator for former FloridaGovernor (and later U.S. Senator) BobGraham, who came to value Reed’s dedica-tion and political instincts so much that heeventually promoted him through the ranksto chief of staff. Before Graham traded thegovernor’s office for the Senate, Reedaccepted the position of chancellor of theFlorida State University system. He held thejob for an unprecedented 12 and a halfyears in a state where, as Reed describes it,“universities are a political sport.”

And like football, it’s a game he learnedto play exceptionally well.

“Football shaped his competitive, bluntpersonality,” said Graham, who considersReed a close friend. “He was not just afootball player, he was a linebacker, whichmeant when the runner got through thedefensive line, his job was to be at the rightplace at the right time and knock the guy’shead off. That’s kind of the way he works.”

Just ask Carol Liu, chair of the stateAssembly’s Committee on Higher Educa-tion, who ran smack into Charlie Reed lastsummer. Reed had arrived one afternoonat his second home in North Carolina forsome rest and relaxation with his wife, onlyto turn around and head straight back toCalifornia at five o’clock the next morningwhen he heard that a key legislative billmight die in Liu’s committee. “I’d never,never forgive myself if I’d have stayed thereand lost it,” said Reed.

The bill authorized Cal State to offerindependent doctoral degrees for the firsttime, in audiology (Au.D.) and education(Ed.D.). That was highly controversial,because California’s 45-year-old MasterPlan for Higher Education reserved theright to offer doctoral degrees for the moreselective, research-oriented University ofCalifornia system. Cal State is meant to

focus on providing undergraduate educa-tion to the top one-third of the state’s highschool graduates; it also offers master’sdegrees. The bill was staunchly opposed byUC, which already had joint Ed.D. andAu.D. programs with Cal State, and by Liu,who also chairs the advisory committee forthe School of Education at UC Berkeley.

But at the eleventh hour, Reed persuad-ed UC President Robert Dynes to removehis opposition to the bill if it was limited tothe Ed.D. and did not include the Au.D.That was part of a calculated strategy onReed’s part. “The idea was to get as muchas we could, but we said if we have to giveup something, we’ll give up the Au.D.,” hesaid.

“I don’t think of it as a horse trade somuch as the best way to go about it,”Dynes explained. “And once we got ouregos out of the way, we both came to thesame conclusion,” he said: that it madesense for Cal State to offer the Ed.D., butthat UC, with its medical facilities andhealth care expertise, should continue topartner with Cal State for the audiologydegree.

After an intense lobbying effort orches-trated by Reed and the bill’s sponsor, stateSenator Jack Scott, chair of the SenateCommittee on Education, it passed out ofLiu’s committee on a 5-2 vote. “I expectedit to be a very hard fight. And it was a veryhard fight,” said Scott, who was subse-quently named one of two “legislators ofthe year” by Cal State. Later, much toScott’s delight, the entire Assembly and theSenate approved it by overwhelming mar-gins. “[Reed] knows how to get things donepolitically,” said Scott, who, like Reed, is aveteran of both politics and higher educa-tion (he served as president of two commu-nity colleges). “He’s quite indefatigable inthe pursuit of things.”

People who know him say the deal wasquintessential Charlie Reed.

“The average college administrator, thebest you can get is Poly Sci 101,” saidAssemblyman Dymally. As chair of theAssembly’s Budget Subcommittee onEducation Finance, he has been impressedby Reed’s accessibility, responsiveness andsavvy. “But he’s Poly Sci Pragmatic 101.”

“He’s a consummate politician,” saidCalifornia Secretary of Education AlanBersin, who also counts himself amongReed’s many fans. “Even when you end upbeing in a big dispute with him, he’s a goodcompetitor. He could persuade you thatsomething was in your interests even whenyou didn’t think so originally.”

That was not the case with Carol Liu.She still believes that the bill was a mistake,and that the new degree will suck preciousresources from Cal State’s undergraduateprograms. “This is an end run by CharlieReed to get around the Master Plan,” saidLiu, who saw herself as its protector andwas peeved that the UC administrationabandoned the fight. “It’s the camel’s noseunder the tent.”

Exactly, said Reed, adding that it’s abouttime the Master Plan was revisited. Afterall, he noted dryly, “The U.S. Constitutionhas been changed a few times, too.” He ishappy to leave the Ph.D. programs to theUniversity of California system, but hehopes Cal State’s Ed.D. program will leadto approval of more Cal State applied doc-

toral degrees. “That’s going to change thecharacter of Cal State,” he said, by addingprestige and name recognition to the insti-tution. (It could use some: When Reedintroduces himself as chancellor of CalState, people often assume he means theUniversity of California.)

So was it a win, a loss or a draw for CalState? “We won,” Reed declared withouthesitation. “Absolutely.”

And winning, to Charlie Reed, meansscoring one for the students. That is whyReed was at the state capitol in May, lobby-ing alongside students, presidents and otherCal State officials for a financial aid bill thatCal State and the California State StudentAssociation had co-sponsored. “I think heworks hard for the students and really triesto do what’s best for the institution,” saidJennifer Reimer, CSSA chair for the pastyear, explaining why the CSSA gave Reedits most recent Administrator of the Yearaward.

Reed is equally popular with the univer-sity system’s presidents, who say he is aleader they can trust. Yes, he’s brusque. Yes,he’s impatient. Yes, he’s demanding. But,they say, he’s also honest, reliable and opento hearing their ideas. Ruben Armiñana,president of Sonoma State University, callshim “a pussycat with a really loud meow.”

Paul Zingg, president of Cal State Chico(also known as Chico State) uses a differentanimal analogy to describe Reed. “He’ssomething of a bull in a china closet,” Zinggsaid. “But I mean that positively. You knowhe’s in the room. And that’s good: to havefolks be aware when Cal State is in theroom. Charlie’s been very effective inannouncing our presence and tying ourpresence to the agenda for the state ofCalifornia.”

Reed does not receive such high marksfrom some Cal State faculty and the CalState unions. But the days of faculty pick-eters and votes of no confidence—inReed’s first year on the job, they werepassed by more than a dozen campus facul-ties, incensed over what they perceived ashis disrespect for them—are long gone.

Still, there’s no love lost between the Cal

Reed has been focusedon improving and

expanding Cal State’steacher training

programs, which havegrown 65 percent since he arrived.

California Assemblywoman Carol Liufailed in an attempt to keep Cal Statefrom offering doctoral degrees.

RO

DSE

AR

CE

YFO

RC

RO

SSTALK

California State UniversityStudents: 405,000

Campuses: 23

Faculty: 22,500

Total employees: 44,000

Percentage of students who areminorities: 55

Ethnic breakdown of students: 45percent Caucasian; 26 percentHispanic; 15 percent AsianAmerican; 7 percent AfricanAmerican; 5 percent Filipino; lessthan 2 percent Native Americanor Pacific Islander

Average age: 25

Percentage of undergraduates whoare first-generation collegestudents: About 30

Percentage of freshmen who needremedial classes: 55

Number of annual graduates: 82,000,about half of all the bachelor’sdegrees and a third of the master’sdegrees awarded annually inCalifornia

Average annual cost: $3,164continued on page 7

CROSSTALK Page 5CROSSTALK

the errors of the College Board may seemironic but, in fact, it is emblematic of thegroup’s history. From its start in 1986,FairTest has played the role of outsider inthe clubby, often opaque world of stan-dardized testing. It has specialized in prick-ing the reputations of the College Boardand other institutions, arguing that theirmuch-feared tests are often faulty bydesign and, more often than not, fail intheir primary mission of predicting studentsuccess.

Upstairs, in the remaining office,Schaeffer said the reprieve has givenFairTest the chance to continue offering itscontrarian services. “There’s always beencertain groups who have been attracted tous because we offer the other side of thestory,” he said. “If you want a non-industry,

non-establishment view of the testingindustry, we can provide it. Frankly, there’sno one else who can do that.”

Over the years FairTest and its allieshave made notable gains in their strugglewith the industry. The testing process nowis more open, and industry research isavailable to the public. Test questions con-tain less bias. And the SAT and its mid-western rival, the ACT, have been strippedof some of their fearful power by theacknowledgement of test makers that test

scores are not immutable but can bealtered through coaching.

Throughout, FairTest has proved diffi-cult to ignore because of its aggressivenessand in-your-face style. When the groupannounced its founding in 1986, for exam-ple, it did so at the College Board’s biggestevent of the year, the College BoardForum, where it proceeded to lambaste theSAT for various alleged biases againstminorities and low-income groups.

And just recently, when Schaefferappeared opposite Gasper Caperton, pres-ident of the College Board, at a New Yorkstate hearing on the SAT scoring scandal,Schaeffer told legislators that the break-down in scoring proceeded from the factthat the testing industry “has no enforce-able quality control standards and lacksbasic accountability to students, teachersand the public.

“The truth is, there is stronger publicoversight and control over the food wefeed our pets than for the tests adminis-tered to our children.”

This approach, essentially political, doesnot mesh easily with the academic style ofthe psychometricians and administrators ofthe testing industry, and it has not wonFairTest many fans within that world.Several prominent members of the indus-try, in fact, refused to comment on FairTestfor this story.

One such leader, Kurt M. Landgraf,president of the Educational TestingService, not only declined to commenthimself but had an ETS spokesman conveythe message that the entire organizationwould remain mute on the subject.

Wayne Camara, vice president for re-search at the College Board, was one ofthe few willing to discuss the group. Afterexpressing his support for several of Fair-Test’s positions on standardized testing,Camara then ripped into their brashapproach, particularly the recent commentcomparing the SAT to pet food.

“That’s a great sound bite,” he said.“But what does it mean? It’s not like we’re

manufacturing pet food, where youopen up a can and test it for thenutrients. I mean, it’s a spuriousissue. What regulatory body wasgoing to catch the scoring error?Would this (regulatory) agencywatch them scoring the test, over-seeing what they are doing?”

In actuality, FairTest’s approachis more or less the classic strategyof underdogs in the world of publicpolicy. Snappy language and soundbites are used by small players toattract attention when they arehopelessly outgunned by largerrivals. With FairTest, the brashnesshas given the group an influencefar larger than its tiny size and bud-get would suggest.

That influence extends to col-lege admissions officers and highschool guidance counselors aroundthe country where FairTest’s argu-ments are widely known and oftensupported. In many such officesthe decades-long willingness toaccept SAT or ACT scores as holywrit has been broken, probablyforever. And in its place, a morecomplex system of assessing stu-

dents has arisen.The most vivid evidence of this change

can be seen on the FairTest website(FairTest.org), which now lists more than730 colleges and universities around thecountry that allow some or all applicants toforgo submitting test scores for admission.Some institutions allow all students toapply without test scores, and base theirreview on high school grades, portfolios ofstudent work, personal interviews and oth-er material. Other colleges allow testscores to be omitted only if students haveachieved grade point averages of a certainlevel or higher.

The 730 institutions on the list include awide spectrum ranging from state universi-ties to elite private schools. No Ivy Leagueschools have gone test-optional, but,according to FairTest, the list now includes25 of the top 100 liberal arts colleges in theU.S. News and World Report rankings.

Actually, FairTest did not originate thetest-optional movement. That role falls toBates College in Maine, which took itsaction a year before FairTest was founded.But FairTest has tirelessly promoted theidea that students and colleges are betterserved when admissions officers employ anarray of assessment measures rather thanrelying on test scores as a principal guide.

“FairTest has acted as a bully pulpit fortest-optional,” said William Hiss, Bates’vice president for external affairs, whoserved as its admissions officer when thecollege made its original decision. “Theyhave also acted as a visible presence for abroad movement that questions the valuesof standardized tests and the way they areused in America. I think that amounts to avaluable service.”

While Bates and FairTest both say theyhave kept an arms-length relationship, theBates experience nonetheless has proveninvaluable to FairTest’s argument that stan-dardized tests have dubious value in pre-dicting the success of college students.

The results of the Bates program havebeen documented over the 21 years of itsexistence, and some of the results haveproved startling. Bates has found, forexample, that students who did not submittest scores, known as “non-submitters,”maintained GPAs that were virtually the

same as submitters. The graduation ratesof non-submitters were also virtually thesame as submitters.

Those results are all the more salientbecause Bates is a highly selective college,and test-submitting freshman have highaverage test scores. So the non-submittersat Bates compete with high-end SAT scor-ers, and differences in outcomes still arehard to detect.

Hiss said Bates’ experience has convert-ed him and other college officials to thetheory of multiple intelligences advancedby Harvard educator Howard Gardner. Nosingle test can measure the different formsof intelligence, talents and skills in youngpeople, Hiss said, and such a test inevitablywill cut out some promising studentswhose skills do not appear on the testresults. Such a process, he said, raises gravequestions for colleges and the country as awhole.

For one thing, he argues that rejectingstudents who would otherwise thrive in

college can have crippling impacts on theirlives, possibly pushing them from collegealtogether and leaving them with careerchoices that are far below their real talents.

And further, he said, the whole nationsuffers. “When you use a test that artificial-ly reduces the pool of people who could goto college and succeed, you are truncatingthe number of educated people availablefor higher-level jobs. That is terrible eco-nomic policy,” said Hiss.

In Cambridge, Schaeffer says FairTestnow receives several phone calls a monthfrom one college or another asking aboutthe process of going test-optional. In thelast three years the list has grown by morethan 200 schools.

“We expect to see the growth (of thelist) accelerate,” said Schaeffer. “In fact,

FAIRTESTfrom page 1

“There is strongerpublic oversight andcontrol over the foodwe feed our pets than

for the testsadministered to our

children.”—ROBERT SCHAEFFER,

OF FAIRTEST

FairTest’s brashnesshas given the group an

influence far largerthan its tiny size andbudget would suggest.

Every year, more colleges and universities make SAT and ACT scores optional forsome or all applicants, says Robert Schaeffer, FairTest’s national education director.

Laura Barrett, FairTest’s board chairman,thinks college applicants should be judged ontheir overall performance, not just on testscores. continued next page

MJ

MA

LON

EY,

BLA

CK

STA

R,F

OR

CR

OSS

TALK

TOD

DA

ND

ER

SON

,BLA

CK

STAR

,FOR

CR

OSSTA

LK

CROSSTALKPage 6

the question now gets raised as to whetherwe are reaching a tipping point where thenumbers start to mushroom.”

The implication of the test-optionalmovement—that the SAT and ACT areexpendable—has clearly hit a sensitivenerve within the industry, and there hasbeen at least one attempt to erode its signif-icance.

In 2002, the College Board assigned tworesearchers to conduct a study of FairTest’slist of test-optional schools which conclud-ed that FairTest had skewed the list, exag-gerating its size.

At the time, the list contained 390schools. The College Board claimed that 52of the institutions on the list did not belongon the list because, in fact, they requiredadmissions tests for all students. “Clearly,the FairTest list…is misleading,” the studysaid, and later concluded, “It is imperativethat the number of SAT/ACT-optionalinstitutions not be overestimated.”

But FairTest officials say it was theCollege Board study, not their list, that con-tained the error. “There were no 52 col-leges that didn’t belong on the list,” saidSchaeffer. “We review the list all the time,and we are vigilant about pulling off anycolleges that get placed there by mistake.I’m not saying they fabricated their list,because I don’t know how or why the mis-take was made, but their claim just wasn’ttrue.”

Schaeffer’s complaint appears to havesome justification. The names of the 52institutions were not supplied by the study,but the College Board made them availableto National Crosstalk after a request. A ran-dom spot check of five colleges on the listrevealed that all five have test-optional pro-grams in one form or another, and all fivehad them at the time of the study.

When FairTest rented its first office justoff Harvard Square in 1986, its future

impact on the education world would havebeen hard to predict. Among other things,it was the product of a political odd couplewho shared almost nothing except a deepsuspicion of standardized testing of allkinds.

John Weiss, a college drop-out and left-leaning political operative, had first becomeinvolved in the test reform movement inthe late 1970s, when he worked forMassachusetts Congressman MichaelHarrington. Those reform efforts eventual-ly fizzled and Weiss repaired to Maine towork in community organizing.

Weiss was still in Maine when, one day,he was approached by a private detective.The detective told him he had been sent bya man named J. Patrick Rooney who want-ed to talk about standardized test reform.The detective gave him Rooney’s phonenumber.

“Rooney and I talked and at first I said Iwasn’t interested. I didn’t want to start anew organization. I was burned out, that’swhy I went to Maine,” said Weiss, who isnow publisher of the Colorado SpringsIndependent, an alternative weekly, and amember of FairTest’s board. “Then I gotcurious and asked how much money wasavailable. Rooney said $750,000. Well, thatwas a lot of money back then. So I thoughtfor a minute and said, maybe I am interest-ed.”

Rooney, it turned out, was the founderof the Golden Rule Insurance Co. ofIndianapolis, a wealthy man and politicallyeccentric conservative who also had cham-pioned civil rights throughout his life.Rooney’s company aimed many of its prod-ucts at blacks in the midwest, and his inter-est in standardized testing was piqued whenhe discovered that white insurance sales-men were passing the licensing exam inIllinois in large numbers but black salesmenwere not.

The exam infuriated Rooney. “In myjudgement the (Illinois) testing was used fordiscrimination purposes,” he said. “Theconstruction of the questions had a dis-parate impact on minority people, and Ibelieve it was intended.”

Rooney sued Illinois and the Edu-cational Testing Service, which providedthe tests for the state. The result, which isstill known as the “Golden Rule Settle-ment,” committed the state and ETS toreform the way questions are formulatedfor its licensing tests.

When Rooney called Weiss, his objec-tive was to expand the reforms he had wonin the lawsuit to cover all types of standard-ized tests, from college admissions to K–12and employment testing. It was an ambi-tious plan. At one early point, after Weisshad recruited Schaeffer to join him, the twoconstructed a back-of-the-envelope organi-zation chart that showed they would need astaff of nine to advance their cause on allthree fronts.

They never quite made it. Rooney con-tributed several million dollars to FairTest’soperations over a five-year period, and hewas followed by grants from the Ford,Joyce and McIntosh Foundations. Thegroup hit its high-water mark in the late’90s when the staff grew to seven personsoccupying two floors of the current officebuilding.

Laura Barrett, FairTest’s board chair-

man, said that, even then, the struggle withthe large test makers was hardly a battle ofequals. “On one side you have these verylarge institutions that make a lot of moneyfrom testing. And they spend it on promot-ing their products. On the other side youhave this small organization that representsthe constituency of people who have con-cerns with testing, but nobody makes mon-ey from that. So it’s been tough.”

Soon it would get tougher yet. By fall2005 all three of the supporting foundationshad dropped their support and FairTestwas surviving on crumbs. Several members

of the board made personal donations thatallowed them to keep the doors open tem-porarily, and it was decided to give Neilland Schaeffer several months to generatesome backing.

No one is certain why the foundationsupport dried up but Neill believes part ofthe reason lies with George Bush’s NoChild Left Behind legislation that mandatesK–12 testing across the country.

“It’s affected the foundations in thesense that they perceive there’s a nationalconsensus about No Child Left Behind andthat more K–12 testing is inevitable,” Neillsaid. “They see Ted Kennedy and GeorgeBush in alliance on this, and they’re askingthemselves why they should fund this smallgroup (FairTest) that’s saying no, no, it’s notgoing to work, it’s bad news.”

The FairTest leaders also acknowledgea more difficult truth: their group is well-known for what it stands against—stan-dardized testing in most of its forms—butless well known for what it supports.

In many admissionsoffices the decades-long

willingness to acceptSAT or ACT scores as

holy writ has beenbroken, probably

forever.

Diane Ravitch, education professor atNew York University and senior fellow atthe Hoover Institution, said she agrees thatstandardized tests have their issues but thatFairTest has never met a test it liked. “Inmy experience, FairTest is opposed to allstandardized tests,” she wrote in an email.“I don’t know of any that they think is‘fair.’”

This view, not rare in the educationworld, may also have hurt the group interms of foundation funding. Foundationsoften prefer to fund organizations that pur-sue a benign course toward their goal.FairTest, in the words of one critic, maypresent to the foundations as “too edgy, toonegative.”

But, in fact, FairTest has long promotedits own view of the way student assessmentshould work. That approach—whetherapplied to college admissions or the K–12arena—resembles the “portfolio” methodused at some colleges, whereby studentspresent a multi-layered profile of their highschool careers both inside the school andout.

FairTest would have K–12 teachersevaluate students individually for their pro-ficiency in various subjects, and the portfo-lios would include samples of essays, pro-jects and other work that revealed theirtalents or deficiencies.

Though any individual evaluation wouldinvolve some subjectivity, Neill says, theevaluation of an entire school of studentsunder this system would prove far morereliable and revealing than the single multi-ple-choice test now used by many schooldistricts.

Barrett, who once served as executivedirector of the group, says this type of stu-dent assessment has been tried successfullyby a few districts but the effort has notdrawn much attention. “It’s hard to explain,it’s complicated and you can’t reduce it to anumber,” she said.

At least one member of the FairTestboard argues that the rap about negativityis a red herring and the group should notapologize for playing the role of critic.Deborah Meier, a founder of progressive

from preceding page

Indianapolis businessman J. Patrick Rooney contributed several million dollars toFairTest in its early years.

CLIN

TK

ELLE

R,B

LAC

KSTA

R,FO

RC

RO

SSTALK

Educator Deborah Meier says FairTestcan “keep the testing companieshonest—there’s no one else who doesthat.”

PETE

RFI

NG

ER

,BLA

CK

STA

R,F

OR

CR

OSS

TALK

CROSSTALK Page 7

schools in New York and Boston and aformer MacArthur Fellow, said, “I’d thinkthat the foundations would want to keepFairTest around just to keep the testingcompanies honest. There’s no one else whodoes that. The testing companies operatein a world of secrecy, and they have thispower over people’s lives. We need acounter-weight organization that opens upthe process and tells us the other side ofthe story.”

Bob Laird, former undergraduate

admissions director at the University ofCalifornia, Berkeley, says that FairTest’srole as counter-weight also has been valu-able in college admissions offices. “TheCollege Board is very skilled at building aweb of relationships with deans, admissionsofficers and college presidents,” he said.“They are never so direct as to say, ‘We areinviting you to a conference at the Toronto

Four Seasons, and then we expect you touse our products,’ but the connectionnonetheless gets made.

“FairTest is valuable because they areaddressing the other end of that equation.They face a Sisyphean task in many ways,but they are making gains.”

And what of the future? Camara, theresearch vice president at the CollegeBoard, predicts that the movement todiminish the role of the SAT and ACT willbe limited by the realities of the admissionsprocess, especially at large schools.

Camara told the story of a visit he paidseveral years ago to the admissions office atUCLA. That year, he said, UCLA hadapproximately 4,500 spaces in its upcomingfreshman class and had received more than40,000 applications. Of those, about 10,000applicants had high school GPAs of 4.0 orhigher.

“So UCLA was looking at 2.5 appli-cants with 4.0s for every available spot,”Camara said. “In a situation like that, howare you going to make the decision aboutwho gets in? Do you flip a coin? Or do youuse the SAT or ACT?”

Laird is not so sure that the tests wouldbe the best way to solve that dilemma.When the UCLA story was described tohim, he laughed. “At Berkeley we hadyears where our situation was moreextreme than UCLA’s. But I’d say, yes, youcertainly could make the decision withoutthe SAT.

“You look at each applicant, not just interms of their numbers, but in terms of

their range of accomplishments and theenvironment they come from. What courseload did they take? What was their highschool like? What kind of community didthey come from? You can get a compre-hensive picture of what the kid achievedversus what was available to him or her.That’s what we did at Berkeley, and itworked extremely well.”

For Laird, the growing perception of thelimited usefulness of the SAT suggests thatits greatest days might have passed. “I thinkthe College Board is probably preparingfor the day when the SAT is no longer itsmost profitable vehicle,” he said.

As for the future of FairTest, prospectshave improved, but a return to flush timesis far from guaranteed. The group receivedseveral small grants this spring, and theinflux of private donations means that thepresent, scaled-down operation can contin-ue into next year.

But Neill and Schaeffer would like tosee the organization return to its formersize of seven or so staff members. “I feellike we’ve moved out of critical care andnow we’re ready for rehabilitation,” saidSchaeffer.

That will require a several-year commit-ment from a foundation or private patron.The group’s request for funding is nowbeing considered by several foundations,and decisions are expected within severalmonths.

There is another issue that facesFairTest. Both Neill and Schaeffer haveworked at testing reform for decades now.

Their hair has turned gray during theirtenure, and their years remaining at thehelm likely are not long.

So who will pick up the cudgels whenthey have left?

Schaeffer laughs at the question. “Wehad a great pool of talented young people.The only problem is, we had to lay themoff. Maybe we should try and find outwhere they went.” u

Robert A. Jones is a former reporter andcolumnist at the Los Angeles Times.

Students who do not submit test scoresdo as well at Bates College as thosewho do, says William Hiss, vicepresident for external affairs.

FairTest has tirelesslypromoted the idea thatstudents and collegesare better served when

admissions officersemploy an array ofassessment measures

rather than relying ontest scores.

State administration and the faculty, whofeel they are overworked and underpaid.“Certainly there’s a lot of faculty anger overthe salary and workload situation,” saidTed Anagnoson, immediate past vice chairof the Statewide Academic Senate and aprofessor of political science at Cal StateLos Angeles. “Probably too much of it isdirected at the Board of Trustees and Char-lie. Probably it ought to be directed more atthe state.”

In the coming academic year, Cal Stateofficials say, average faculty salaries areprojected to lag 18 percent behind those atcomparable institutions, more than 26 per-

cent for full professors. That is in large partdue to the hit Cal State took during Cali-fornia’s budget crisis: between 2002 and2005, the Cal State budget was slashed by$522 million, about 12.5 percent of its cur-rent $4 billion budget.

At the behest of California GovernorArnold Schwarzenegger, Reed and UCPresident Dynes negotiated a six-year high-er education compact that provided anadditional $218 million to Cal State thisyear, but that only covered a 2.5 percentincrease in enrollment and a 3.5 percentincrease in salaries, the first in three years.The compact also provides for continuedfunding for the projected 2.5 percent annu-al enrollment growth, as well as steadyincreases in base funding of three percentnext year, four percent the following yearand five percent during the last three yearsof the agreement.

Some legislators were miffed that theyweren’t included in the compact negotia-tions, and thought Reed and Dynes mighthave done better. But Reed defended thecompact as fair. And California Secretaryof Education Bersin praised it as politicallypragmatic, given the state’s dire fiscal situa-tion at the time. “Charlie’s been around theblock enough to know that pigs get fed andhogs get slaughtered,” Bersin said. Trans-lation: You won’t survive long if you try tograb more than your share.

But now that the state’s economy isimproving, union leadership has been criti-cal of Reed for failing to advocate for addi-tional funding. “Initially they said it wouldjust be a floor,” said John Travis, professorof government at Humboldt State Univer-sity and Cal State Faculty Association pres-

ident. “They have treated it as a ceiling.They do not ask for anything more than thecompact, and we believe that is just notenough.”

Travis doesn’t have many kind words tosay about Reed, whom he criticized for not

listening to the faculty, and for raising annu-al tuition and fees. “It’s always been kind ofsurprising to us that he distrusts the advicethat comes from the people who are doingthe business of the university,” he said.

But even Travis acknowledged thatReed isn’t completely to blame for what hecharacterized as the union’s “dysfunctionalrelationship” with the administration. “Thispredates Charlie. It’s always been very diffi-cult to bargain with the administration.”And he said he was pleased that Reedrecently hired a consultant to help improvehis relationships with Cal State employeeunions. “I think all of the labor unions seethis as a positive development. It’s a recog-nition of a problem,” said Travis.

Reed, for his part, said he thinks therelationship has already improved some-what; he also has said that he recognizes theneed to close the salary gaps lest they jeop-ardize the future quality of Cal State. And

in fact, the Cal State Board of Trustees hasapproved a five-year plan that begins toaddress the issue.

But Reed said that the union leadershipis not grounded in fiscal reality. “They thinkthere’s some money machine somewhere,”he said, with exasperation.

Reed doesn’t have a money machine,but he has told his presidents they mustraise more funds from the private sector,which he says has been largely untapped byCal State. “California has so much wealthcompared to most other states,” said Reed.“And we have to figure out how to accessthat wealth.”

Meanwhile, he believes student tuitionand fees should continue to increase tenpercent a year until students are picking up25 percent of the total cost of their educa-tion. Currently, he said, tuition accounts forabout 23 percent. Even with substantialtuition hikes over the past few years, the$3,164 average annual cost of attending CalState remains far below the national aver-age cost of attending a public four-yearinstitution, which this year was $5,491.

Reed could not say how much longer hewould remain at the helm of Cal State. Buthe clearly is in no hurry to step down.Because California is ten to 15 years aheadof the rest of the country in terms of popu-lation trends, he believes that Cal State canserve as a national model. And he wants tomake it a good one.

Besides, said Reed, “I think I would dieif I didn’t go to work.” u

Kathy Witkowsky is a freelance reporter inMissoula, Montana, and a frequent contrib-utor to National Public Radio.

Under Reed’sleadership, Cal Statehas garnered national

attention for innovativeprograms designed

to help students prepare for college.

John Travis, president of the Cal StateFaculty Association, says ChancellorReed largely ignores advice fromfaculty members.

REEDfrom page 4

KE

LLIE

JOB

RO

WN

FOR

CR

OSS

TALK

CROSSTALKPage 8

ALeftyUnderEveryLecternConservative crusader David Horowitz pusheshis “Academic Bill of Rights”By Susan C. Thomson

FRESH FROM A NUMBER ofself-proclaimed victories, conserva-tive culture warrior David Horowitz

and his troops are massing for what isshaping up as their broadest attack yet inhis campaign to, as he likes to put it, “takepolitics out of college classrooms.” Theirbattle flag is an “Academic Bill of Rights”Horowitz drafted as an antidote to what hedisparages as the pervasive political indoc-trination of college students by leftist pro-fessors.

For a text, the legions have Horowitz’s

latest book, “The Professors: The 101 MostDangerous Academics in America,” pub-lished in February. A collection of mini-profiles of, as Horowitz broad brushesthem, a rogues gallery of faculty quacks onthe far left, it’s a sharp-shooting, sure-fireattention-getter.

As Horowitz himself says, getting atten-tion is what this crusade of his is all about.And doing that is a skill he has personallyhoned to perfection in almost five decadesas something of a professional—and mer-curial—political polemicist. Though shortof stature, he is long on fervor, quick withwords, avid for the limelight, impossible toignore.

For three years now, Horowitz has beenon his higher-education offensive, advocat-ing his “bill of rights” in campus speeches,testimony to state legislatures and personalappeals to college administrators.

In its broadest strokes, Horowitz’s Aca-demic Bill of Rights is vanilla–bland andeasy to swallow. It calls for classrooms freeof all indoctrination and for ideologicalimpartiality in the hiring, firing and promo-tion of faculty members, and in the gradingand disciplining of students. But whatamounts to the bill’s fine print sends fearfulshivers down the spines of some acade-mics, who see there threats to their ownfreedom, even the specter of a new kind ofMcCarthyism.

It calls for:• Curricula and reading lists in the hu-

manities and social sciences that reflectnot just their professors’ personal view-points.

• Speakers, programs and other studentactivities that “promote intellectual plu-ralism.”

• Intolerance for obstruction of outsidespeakers and destruction of campus lit-erature.

• Institutional neutrality in areas wherescholars in the same field disagree.

In late 2003, when the ink was barelydry on the bill, the American Associationof University Professors went on record assupporting the “non-indoctrination princi-ple” but taking vehement exception to oth-er features the association said could pose“a grave threat” to traditional academicfreedom by leading to quantitative stan-dards for political diversity, requirementsto teach discredited theories, and intru-sions on faculty autonomy by courts,administrators and legislatures.

Now, as a dedicated and watchful foe,the AAUP keeps tabs on state legislatures,where Horowitz’s bill has found some of itsmost enthusiastic recruits. According tothe AAUP’s running tally, lawmakers in 17states have advanced various versions ofthe Academic Bill of Rights. None has yetmade it into law, and only the GeorgiaSenate two years ago went so far as toactually pass something like it, though con-siderably watered-down.

Last year, however, under threat of leg-islation, higher education leaders in Ohioand Colorado agreed to some of the bill’smore palatable points. Horowitz claimedvictory in both states and in Pennsylvania,where the General Assembly established aspecial committee that held hearings onthe political environments for teaching andlearning in the state’s public colleges anduniversities—the most extensive public air-ings so far on Horowitz’s issues. The com-mittee has yet to produce its report.

The Academic Bill of Rights has alsofound favor at the federal level, notablywith U.S. Representative Jack Kingston. In2003 the Georgia Republican floated a“sense of the Congress” resolution featur-ing the bill’s language almost word forword. The resolution didn’t succeed, butsimilar wording found its way into earlyproposals for the House version of thehigher education reauthorization bill.

The softer final version, merely endors-ing campus free speech and students’ rightsto express their beliefs without fear ofreprisal, resulted, in part, from behind-the-scenes lobbying by the American Councilon Education, the chief advocacy organiza-tion for the nation’s colleges and universi-ties.

Those generalities are consistent withACE’s “Statement on Academic Rightsand Responsibilities,” published last yearin obvious, though indirect, response toHorowitz and his “bill of rights.” It pro-claims, “Neither students nor facultyshould be disadvantaged or evaluated onthe basis of their political opinions.” Thedocument also defends “intellectual plural-ism and academic freedom” and “the freeexchange of ideas” on campus while in-sisting that not all ideas “have equal merit”and that government should respect col-leges’ and universities’ need for autonomyon academic matters.

A more direct criticism of Horowitzcame from Jamie Horwitz, spokesman forthe American Federation of Teachers: “Wethink his writings and a lot of his remarks

have been filled with mischaracterizationsand outright deceptions.”

Thirty higher education organizations—among them, the American Dental Edu-cation Association, the College Board, theCouncil for Christian Colleges and Uni-versities and the National Collegiate Ath-letic Association—signed the milderAmerican Council on Education statement.

Terry W. Hartle, ACE’s senior vice pre-sident for government and public affairs,said that the general endorsement of freespeech on campus and of students’ rights toexpress their beliefs without fear of reprisalis “a satisfactory solution to a complicatedproblem.” But, he acknowledged, “Thereare still some people in the higher educa-tion community who are unhappy with oursupposedly giving David Horowitz legiti-macy. He is legitimate. David Horowitz istaken very seriously by higher educationofficials around the country.”

And he’s not going away. When askedto detail his immediate plans, though, hedeclined. “I don’t really want to telegraph,because my opposition is so well funded,where I’m going to pop up next,” he said.

Horowitz insists that legislation isn’t hismain objective. At the same time, however,

Brad Shipp, field director for a Horowitz-sponsored organization called Students forAcademic Freedom that claims chapters orcontacts on more than 180 campuses, said,“Any time a legislator contacts us, we willassist them in any manner they want…We’ll support legislation if it has to come tothat.”

Students from the SAF chapter atFlorida State University testified for a pro-posed Academic Bill of Rights in that statelast year. But, said chapter chairman MattSarrar, “The legislation was only meant toopen the eyes of the universities all acrossthe state.” He sees the organization’semphasis as shifting now from the legisla-tures to the campuses themselves. “Thefuture of this is going to be dealing withindividual universities,” he said, with anemphasis on “helping them develop agrievance process” for conservative stu-dents who believe they have been wrongedby leftist professors.

As that process stands at Florida Statenow, Sarrar said, only individuals can filegrievances, and his group of between 50and 65 members has been unable to inter-cede for students who claim professorshave invited them to drop courses orthreatened them with failing grades orexpulsion from class for their conservativeviews.

SAF’s national office encourages allcampus chapters to report incidents ofalleged abuses and collects them in a “com-plaint center” on its website (studentsfora-cademicfreedom.org). Also posted there—under SAF’s logo, which features threemonkeys in academic gowns and hear-no-evil, see-no-evil and speak-no-evil poses—isa copy of the organization’s student hand-book, detailing how to start and organize achapter, collect and document complaintsand get publicity.

The organization’s goals include, accord-ing to the handbook, persuading universi-ties to adopt the Academic Bill of Rights aspolicy, and getting student governments topass resolutions supporting a Student Billof Rights, Horowitz’s rewriting of his acade-mic bill from a student perspective.

Horowitz said one of his immediate

For three years now,conservative culture

warrior DavidHorowitz has been on

a higher-educationoffensive.

Terry Hartle, senior vice president atthe American Council on Education,says Horowitz “is taken very seriously”by many higher education officials.

David Horowitz contends that many faculty members at U.S. colleges anduniversities try to indoctrinate students with left-wing views.

PHO

TOS

BY

DE

NN

ISB

RA

CK

,BLA

CK

STAR

,FOR

CR

OSSTA

LK

CROSSTALK Page 9

goals is to put the student bill “in the handsof students” so that they are aware of“their rights to a professional non-politicaleducation.” According to SAF’s nationaloffice, campus chapters have yet to suc-ceed with a single university but havescored with at least a dozen student gov-ernments.

On some campuses, chapters of CollegeRepublicans have led the charge. This wasthe case in April at Princeton University,where undergraduates approved theStudent Bill of Rights, with 51.8 percent infavor. Horowitz described the surpriseresult as an “historic victory” for his princi-ples.

Students for Academic Freedom haschapters on both public and private cam-

puses, but the issues they and Horowitzraise loom largest and most menacingly forthe public ones. That’s because they getpublic money, said Shipp. “When you havea taxpayer-funded institution that is allow-ing its employees the ability to discriminateagainst students there for any reason, theirpolitical ideology or religious beliefs, youhave a real problem.”

Horowitz casts the potential conse-quences in economic terms. “The greatestthreat to state funding (of public universi-ties) is the one-sided political domination ofthe left” on campus, he said. And yet, heclaims that, rather than being out for anyprofessors’ jobs, he wants only to expandpolitical dialogue on campus and stop class-room proselytizing. Whether that’s of theright or left, “I couldn’t care less,” he said.

This is a rare protestation of neutrality

from a man whose personal, out-front polit-ical views have always been anything butdisinterested. On most of today’s issues,Horowitz comes down hard on the right.His website, frontpagemag.org, promotesthe military and the Iraq war, cautionsagainst the threat of “global Islamism,”bashes the Palestinian Authority, theUnited Nations and illegal immigration,and promotes his books, including “TheProfessors.”

In that book, he proceeds from thepremise that college faculties are infestedwith leftover 1960s lefties who went tograduate school to avoid the Vietnam draftand, as “tenured radicals,” now misusetheir classroom lecterns as political pulpits.He goes on to offer, in biting prose, a seriesof three- to five-page profiles of academicshe variously condemns as believers inMarxism, racial preferences, same-sexmarriage, or as opponents of the PATRI-OT Act, free-market capitalism, Israel, the“War on Terror,” the Iraq war or U.S. Mid-dle Eastern policy.

Horowitz claims the 101 professorsnamed in his book are a representativesample from colleges and universities,large and small, public and private. Butnine are from Columbia University; seventeach law; and a quarter are engaged inblack studies, women’s studies, peace stud-ies, Islamic studies, “queer” studies or thelike—curricular innovations of the pastgeneration, all of which Horowitz deploresand dismisses as academically fraudulent.

As a counter to Horowitz’s academicoffensive, a coalition of liberal groups—including the AAUP, the American CivilLiberties and the American Federation ofTeachers—launched the organization FreeExchange on Campus, and the websitefreeexchangeoncampus.org, earlier thisyear. They argue, in a 50-page, footnotedrebuttal to “The Professors,” that the bookis based on sloppy research and falsepremises, is full of misstatements and omis-sions, and that it “strongly evokes a black-list.”

Among Horowitz’ 101 professorialpiñatas, he beats longest and hardest onWard Churchill, devoting most of his

book’s introduction to the provocative pro-fessor of ethnic studies at the University ofColorado who ignited a furor for infa-mously referring to the victims of theSeptember 2001 attacks as “little Eich-manns” who deserved what they got thatday. (Free Exchange does not defendChurchill.)

While the book disparages Churchill asa “scandalous figure” of “abhorrentviews,” Horowitz was not above schedul-ing a “debate” with him and advertising itas a drawing card for what he billed asStudents for Academic Freedom’s firstnational conference.

Students were a small minority amongthe 130 registrants for the two-day event ata Washington, D.C. hotel last April, butthey dominated the audience for the eve-ning debate at George Washington Uni-versity.

The 260-seat auditorium was filledalmost to capacity. Projected large on theback of the empty stage was the logo ofYoung America’s Foundation, a co-spon-sor of the event and a group that, accord-ing to its website, supports ROTC, favorsthe rights of campus conservatives and theideals of Ronald Reagan, and condemnsracial preferences, “anti-Americanism inhigher education” and “left-wing campusbias.”

The combatants entered, Horowitzstage right and Churchill stage left, a studyin contrasts before they spoke a word.Horowitz, 67 and stubby to begin with, wasfurther dwarfed by a suit jacket that hungloose and long on him. With his spectacles,trim white goatee and receding gray hairthat gathers in neat, short curls at his neck,he could easily have passed for the collegeprofessor he proudly claims never to havebeen.

In jeans, cowboys boots and an ill-matching black T-shirt and jacket, Chur-chill, 58, stood tall—towering above Horo-witz. His long, straight, middle-parted haircompleted the image of the Native Ame-rican he claims to partly be—falsely, ac-cording to his detractors, Native Americangroups among them.

A local talk show host, serving as mod-erator, lobbed the questions. First: Can pol-itics be taken out of the classroom, andshould it be?

Horowitz answered an emphatic yes,elaborating in pithy, well-practiced soundbites and making eye contact with his audi-ence. “The very basis of a democratic edu-cation is you are taught how to think, notwhat to think,” he said. Churchill, gazingout over the heads before him and speak-ing in meandering sentences, just as em-phatically disagreed. His point: Becausesome academic disciplines are naturallypolitical, and professors naturally haveopinions, intellectual honesty demandsthat they own up to them for their stu-dents.

For the next hour and a half, the ques-tions were pretty much variations on theoriginal one. Answering, Horowitz wasebullient, Churchill dour. The tone wasconversational. No sparks flew in whatturned out to be less a debate than twoparallel monologues. Except when Chur-chill accused Horowitz of “rowing with oneoar” and “going in circles” in his reasoning,

the odd couple barely engaged each other.That comment drew a laugh from an audi-ence that, judging by only occasional scat-tered applause, was largely indifferent toboth men.

Horowitz used some of the time allot-ted him to sneak in a few of his favoritezingers: that college professors can make$100,000 or more a year, get four monthsoff and spend only six to nine hours a weekin class; that education schools teach socialjustice, “code for socialism, or communismor redistribution of wealth”; that socialwork is often taught as “an indictment ofthe free market system”; that teachersunions encourage teachers to indoctrinatetheir students; that institutional racism is “afantasy of the left.”

The debate was called off just in time forChurchill and Horowitz to prepare for ascheduled live appearance on Fox News’“Hannity & Colmes” shout fest. Withmostly the media types sticking around, thedebaters squared their shoulders and staredinto a bank of cameras. While they awaitedtheir cue, somebody, as if to even up thematch, handed Horowitz a box to stand on.

From the only side of the conversationonlookers could hear, it was clear that SeanHannity was taking on Churchill and wassucceeding in getting under his skin. Chur-chill, amid frequent, exasperated proteststhat Hannity kept interrupting him,seemed to be trying unsuccessfully to scorepoints in opposition to the Iraq war. At onepoint he suggested that Hannity owed himan apology. The back-and-forth went onand on, leaving little time for Alan Colmesto do his number on Horowitz, who, al-ways quick with a quip, confessed to feel-ing “like a potted plant” in the proceed-ings. When it was over, Churchill and

Horowitz laughed and shrugged theirshoulders as if to ask, “What was that allabout?” And then they went their separateways.

The conference panelists and speakers,most of them Horowitz disciples, decried,among other things, speech codes, manda-tory sensitivity training and a general lackof, and respect for, conservative thought oncampus. Students told stories of being

In his latest book,Horowitz argues thatcollege faculties areinfested with leftover

1960s lefties who wentto graduate school

to avoid the Vietnam draft.

Ward Churchill, an ethnic studies professor at the University of Colorado who isnotorious for calling victims of the September 2001 attacks “little Eichmanns,”debated Horowitz in Washington, D.C., in April.

U.S. Representative Jack Kingston, aGeorgia Republican, introduced a“sense of the Congress” resolutionincorporating some of Horowitz’“Academic Bill of Rights,” but theresolution failed.

continued on page 14

Page 10

UnnecessaryBarriersThe exclusion of foreignscholars has assumed almostepidemic proportions

By Robert M. O’Neil

WHILE MUCH of the nation’s attention was riveted on the immigration policydebate during the spring of 2006, the academic community worried about aquite different dimension of foreign access to the United States. The exclusion

of visiting scholars from abroad, which had been a growing problem in the years immedi-ately following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, had now assumed almost epi-demic proportions.

A late March letter to the Secretaries of State and Education expressed the deep con-cern of the major higher education groups over the potential impact of such exclusionupon the international programs of America’s colleges and universities. Along with a callfor increased funding of foreign language and international area studies programs, the let-ter urged the Bush Administration to remove “unnecessary barriers to international schol-ars,” with special attention to burdensome visa restrictions.

Evidence of apparently mounting hostility toward foreign visitors was not hard to find.In late winter, Waskar Ari, a distinguished Bolivian historian (with a Georgetown Ph.D.)who had been recruited to a faculty position at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln for thefall of 2005, had waited eight months for the essential visa, unable to obtain any rationalefor the delay that cost him a full academic year. Although Nebraska Chancellor HarveyPerlman insisted that he had “seen no evidence that Professor Ari represents a securityrisk,” neither the visa nor any explanation for its denial was forthcoming. A very public

protest by the American Historical Associationalso went unanswered.

About the same time, three scientists fromIndia were inexplicably denied visas by the U.S.consulate in Madras, even though all had receivedinvitations from U.S. universities, and at least oneof them had been a frequent visitor to U.S. cam-puses. Professor Goverdhan Mehta, an organicchemist and former director of the Indian In-stitute of Science, was greeted by a consular offi-cial—during what he expected would be a routine

interview—with probing questions about the potential use of his research for “chemicalwarfare.” The official accused him of “not being honest,” recalled Mehta, who said that theexperience left him feeling not only “very humiliated,” but baffled about the basis for hisexclusion.

Latin American scholars seem to have encountered special scrutiny and official disfa-vor. Professor Dora Maria Tellez, who once was a leading member of the SandinistaLiberation Movement in Nicaragua, but is now well established as a university professor,was denied permission to enter the United States to accept an invitation to teach at Har-vard. Meanwhile, Latin American historian Miguel Tinker-Salas, a Venezuelan-born facul-ty member at Pomona College, found himself the wholly unexpected target of highly intru-sive questions and of manifest suspicion by Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies, whoentered his office without warning as he awaited students in early March.

During that very week, the State Department inexplicably denied visas to all 55 Cubanscholars who had planned to attend an international conference in Puerto Rico of theLatin American Studies Association. This was hardly the first such affront to visitors fromCuba, though it was the most sweeping. Three years earlier, an unexplained delay in grant-ing visas to Cuban delegates bound for the same scholarly gathering kept more than half ofthem from attending the meeting, held that year in Dallas.

Professor Carlos Alzuguray Treto, an expert on U.S.-Cuban relations and a frequentlecturer at American campuses (including Harvard and Johns Hopkins), was denied thevisa that would have enabled him to deliver a keynote address at the Latin AmericanStudies Association annual meeting. That same spring, a Miami University geographerwho had planned the weeklong return visit of a Cuban scholar to his campus lamented thedenial of a visa to his putative guest, noting that the exclusion of such colleagues represent-ed a “disturbing sign of the many impacts of the ‘war on terror.’”

Of all such exclusions, by far the most visible and contentious involves Islamic scholar

Tariq Ramadan. In the summer of 2004, when he was based in Geneva, Ramadan hadbeen offered, and had accepted, the Henry Luce Professorship in the Joan Kroc Instituteat the University of Notre Dame. His furniture had already been sent to South Bend,Indiana, and his children were enrolled in school there for the fall.

Having been a frequent visitor to the United States, and a popular lecturer at Harvard,Dartmouth, Princeton and other campuses in recent years, Ramadan assumed that his per-manent entry this time would be routine, and that he could plan on taking up his new acad-emic post in the fall semester.