Finding the Self by Losing the Self: Neural Correlates of Ego-Dissolution Under Psilocybin

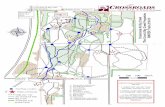

Crossroads Jerusalem: Losing Ego, Giving Self

-

Upload

eve-michal-willinger -

Category

Education

-

view

194 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Crossroads Jerusalem: Losing Ego, Giving Self

Michal Willinger28/2/2012Psych Skills II – Final Paper

Losing Ego, Giving Self

When selecting internship placements at the end of our second year in our BA

in Psychology, I wanted a placement that would introduce me to the misfits of

civilization. The ones who are considered lost cases, the ones who are called crazy,

institutionalized, told their futures are dim and their former dreams impossible, that

they have a genetic predisposition to not belonging, to not being any good in the

world – to catch them at this moment of despair, to meet them exactly where they are,

and to be a source of positive and realistic vision for them for their own future and

beliefs. In my own family there’s a long history of schizophrenia, bipolarity and

depression. There’s the typical response and there is the extraordinary response – the

difference is just a hair’s width of experience that comes from self-empowerment on

the brink of self-defeat. From my own experience I have tools and empathic

understanding that I can give to others in this mode – and it is a space where so few

willingly find themselves with the desire to make a positive difference in someone’s

life, not simply medicate them.

The three figures I chose to incorporate into this paper are Carl Rogers, Loren

Mosher, and Daniel Wolpert. They are from entirely different fields – the first, an

interpersonal psychotherapist, the second, a schizophrenia expert and activist, and the

third, an academic neuroscientist. What they all hold in common is a universal

understanding of the human mind where every brain gets a fair chance to succeed.

The trick is only to provide the correct environment and to encourage the building of

skills that allow a person to be the best of their potential over time and practice.

Carl Rogers writes in one of his more recent papers (Rogers, 1992) about the

environmental conditions necessary for deep changes in personality – holding that

every person is unique and able to become better, and that no behaviour or cycle is

necessarily fixed. The conditions are as follows:

1. Two people in psychological contact.

2. One, presumably the client, in a state of incongruence, being vulnerable, or

anxious.

3. The therapist experiences unconditional positive regard for the client.

4. The therapist experiences empathic understanding for the client’s internal

frame of reference and endeavours to communicate this experience to the

client.

5. This communication is to the minimal degree necessary.

What may appear a radical negligence on the part of the therapist to input knowledge

and skills into the client is in fact an incredible act of courage – the courage to allow

the client to be as he is, and to be accepted. Exactly why this works is left for the

remaining two theorists to explain; first by Dr. Mosher, in terms of social acceptance,

and second by Daniel Wolpert, in terms of the neurological understanding of “self”.

Dr. Loren Mosher created a project termed “Soteria” in the 1979 outside of

San Francisco, California in the United States that endured for twelve years before its

success brought concern from large pharmaceutical companies that a treatment model

without neuroleptic drugs could potentially render the current psychiatric model

obsolete. Approval for expanding the project from the American Psychiatric

Association, who relies heavily on support from big pharmaceutical companies, was

repeatedly opposed. In particular, Mosher was concerned by “serious long term

effects: tardive dyskinesia, tardive dementia and serious withdrawal symptoms”

(Mosher, After twelve years in operation, Soteria patients were significantly less

likely to be readmitted to a psychiatric hospital, significantly more likely to be able to

live on their own or with peers rather than remain dependent on family members, and

significantly likely to exhibit less symptoms of their illness, as measured by three

independent raters (Bola & Mosher, 2003). Furthermore, these patients were free to

come and go at any time, were treated in a social context without any routine use of

medications, and in a home-like environment in contrast to the traditional hospital

setting, staffed by medically-trained nurses with routine daily injections and

medications. Mosher’s work provides concrete evidence that psychiatric illnesses can

be significantly improved in an interpersonal context and that the improvements are

objectively more effective than the current psychiatric model. In his 1998 speech to

the American Psychiatric Association, explaining his reasons for choosing to resign

after being a member of the organization for 35 years, he explained, "No longer do we

seek to understand whole persons in their social contexts," he told the APA. "Rather,

we are there to realign our patients' neurotransmitters. The problem is that it is very

difficult to have a relationship with a neurotransmitter, whatever its configuration"

(Redler, 2004).

What then, is going on the level of the neuron? If medications aren’t needed

in the majority of cases in order to solve the problems of someone in trouble, what is

it about the therapeutic relationship that works? Carl Rogers explains that a patient’s

vulnerability, anxiety and incongruence “refers to a discrepancy between the actual

experience of the organism and the self picture of the individual insofar as it

represents that experience” (Rogers, 1992). Wolpert elaborates this concept with his

work done on the brain and self-subtraction during movement. Using motor control

as an operational definition of the self, Wolpert’s lab uncovers how “motor control

can be considered as a continuous decision-making process in which.. decision-

makers can be risk-sensitive with respect to this uncertainty in that they may not only

consider the average payoff of an outcome, but also consider the variability of the

payoffs… motor behaviours can be explained as the optimization of a given expected

payoff or cost” (Braun, Nagengast & Wolpert, 2011). In another paper, Wolpert

examines mis-coordination between two people (imagine walking down a hallway

and trying to choose whether to move to the right or left to allow someone to walk by

you) and finds success is due mainly to mutual information and the ability of each

person’s movements to reduce the uncertainty of the other person with his own

movements (Wolpert & Braun, 2011). These findings suggest that the interpersonal

relationship is actually training the incongruent client to match the congruence of the

therapist over time, as the relationship develops into a healthy, syncopated working

model of communication. This model is subsequently mimicked with other

relationships as it is internalized over time and the ‘uncertainty’ of actions, behaviours

and language is reduced through social training in a safe environment.

Crossroads is an at-risk teen center in Jerusalem that seeks to provide a safe

and accepting environment for teens who find themselves without a safe place to be.

Whether this lack of safety is material, social or based solely on the teen’s perception

of their surroundings is never questioned or devalued, rather Crossroads social

workers are trained to communicate with each client on their own terms and to

establish trust before delving into deeper issues. Employees are also trained to focus

on material problems and concerns and to make sure the teen is given space and

accepting attention in order to decide for him or herself whether or not to proceed

with the free-of-charge therapy the center provides.

My own experience with Crossroads has been a combination of awe and

caution. In my first four hour volunteer experience, a teen named Moshe, who

everyone calls Mooshie, leapt on the couch next to me exclaiming, “Now you

understand, we’re gonna have a conversation!” and proceeded to envelop me in his

ideas of conformity, the arbitrary nature of authority and the frustrations of ageist

attitudes. It was as if I was speaking to an old friend from my former self 15 years

ago. I was so touched by the sincerity, the truth-value of his observations and yet as

an older person the distance that time afforded me from the frustrations he was only

just experiencing for himself. I did my best to support his words with reflecting

understanding and non-judgement of his ideas, and to encourage his free thought, and

to see if he could name his real intentions behind things in him that made strong

emotions. The second time I came I spent a lot of time with Jimmy, a teen that has

been coming for a few years, and other boys as they came in and out, gathering in a

circle and making a safe space for conversation by being positive, engaging for

everyone without exclusion. By the fourth session I started to come prepared with

enigmas – little riddles that broke the ice and challenge the teens to think outside of

the box for simple solutions. In a relatively short time I began to feel connected to

this place, even though I had barely scratched the surface of how the center actually

works.

But how is it possible to keep a distance when it appears in a teen's life there is

such a real and gaping lack of alternatives? I made encountered my first personal

challenge with the case of Yosi, a slender boy of about 19 who refuses to wear shoes.

Yosi is brilliant – his articulation, his grasp of many analytical concepts, and in his

refusal to associate his identity with anything at all. Escaping a strict religious

background in the States, he came to Israel on a Birthright trip and has remained

illegally in the country for nearly three years. He calls no place home, he has many

light friends but makes a point of not putting himself down on any thing or any one –

he feels it is against the very nature of what it means to exist. We spent several hours

talking, and the next week, I saw him on the street outside and he told me he was

coming to the center in a half hour or so, and then he arrived and we spoke again, this

time with Lauren, the social worker I am responsible to during my time there on

Tuesday nights, and the art instructor, Miles. The conversation sometimes became so

casual and relaxed that I found myself forgetting that I was in some sort of therapeutic

position, and I had to keep reminding myself to keep searching for a neutral place.

Yosi left and gave me a doodle he had drawn with his blog address on the back – and

at a crossroads of whether to read it or not, I read it later, and became enthralled by

his writing, his perspective, the swirling mindscapes and drug use, the exploration and

despair, and my heart was touched by this stranger and I wanted so much to offer him

my help. But already I sensed I had gone beyond the boundaries of what Crossroads

is there to do, and realized I had to re-evaluate my approach entirely.

Why did I feel the drive to take a position? Is it somehow my own desire to be

a helper, and less in mind of the long-term safest and greatest good for the center, and

for the teens who pass through there? In order for healing to take place, unconditional

positive regard and empathetic understanding must be from a position of congruence.

A therapeutic role cannot switch to a motherly or even a friendly one – that is not the

position of the therapist. I realized that I had gone too deeply into Yosi’s eyes and I

was no longer neutral about him, I had judgements, ideas, even if they were awe-

inspired ones. There is no positive change that can come about meaningfully in the

relationship if I am already slanted in how I view him, and moreover, I began to

worry if that wouldn’t effect the safe environment at Crossroads – isn’t it just as

important to harbour a safe distance as it is to establish a comfortable trust? I’ve set

my intention for the second half of the year to approach the center in a Rogerian-

viewpoint, where the establishment of self-congruence and a syncopated emotional

tone is key, but without losing myself.

REFERENCES:

Bola, J. and Mosher, L. Treatment of Acute Psychosis Without Neuroleptics: Two-Year Outcomes From the Soteria Project. 2003. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(4), 219-229.

Nagengast AJ, Braun DA & Wolpert DM (2011) Risk-sensitivity in a motor task with speed-accuracy trade-off. Journal of Neurophysiology, 105, 2668–2674.

Redler, L. (2004, July 28). Loren Mosher: US psychiatrist whose non-drug treatments helped his patients. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk.

Rogers, C. 1992. The Necessary and Sufficient Conditions of Therapeutic Personality Change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(6), 827-832.

Wolpert, D. & Braun, D. 2011. Motor coordination: When two have to act as one. Experimental Brain Research. Published online (doi:10.1007/s00221-011-2642-y).