Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

-

Upload

cozy-hannula -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

Transcript of Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 1/31

Women in Architecture: A Proposal of a Longitudinal Survey

Cozy Hannula

Thesis

Submitted under the supervision of Gregory Donofrio to the University Honors Program at the

University of Minnesota-Twin Cities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Bachelor of Science, summa cum laude in architecture.

May 8, 2015

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 2/31

Cozy Hannula

1

Introduction

In 2011, Mattel approached the American Institute of Architects (AIA) with the proposition of

making architecture the career of the “Barbie I Can Be…” doll. This partnership grew into a symposium

designed to explore how architect Barbie could engage young girls in the profession and discuss the

issues involved with women in architecture. At the symposium, discussions were about stereotypes,

current status of women in the profession, what it takes to be successful in architecture, and how

women can shape the future of the profession.1 Currently, about 41% of students receiving professional

degrees in architecture are women (see Figure 1).2 However, only about 25% of people practicing

architecture are women, including both licensed and non-licensed employees.3 Women are also

underrepresented in leadership positions in firms, at 17%.4 The question is: why are women leaving the

profession, why are so few women in leadership roles, and what can be done to retain and support

women architects? The architect Barbie discussion spurred others and committees and organizations

were formed to research and support women in architecture, many of these studies are still in the

beginning stages.

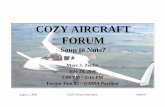

Figure 1: Women in Architecture Statistics

Created by author

Statistics show how the percentage of women in

the profession drops from education to the

profession to leadership positions and awards.

Statistics are gathered from Association of

Collegiate Schools in Architecture, Bureau of Labor

Statistics, and National Center for Education

Statistics

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 3/31

Cozy Hannula

2

Architecture loses women between education and the profession, among other issues facing

women in the profession. For Women are fighting to be recognized for their contribution to this

profession, including a recent petition circulated to retroactively include Denise Scott Brown in the

Pritzker Prize awarded to her business partner and husband Robert Venturi.5 This topic also relates to

research being done more broadly on women in business. There is a wage disparity between genders,

women lack support in the workforce, and a glass ceiling prevents women from advancing to leadership

positions. Sheryl Sandberg’s recent book Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead received a lot of

attention for addressing many of these issues.6 Groups like McKinsey and Company have published

best practices for retaining women in the workforce and have conducted studies to try to understand

what is keeping women from being equally represented in business and especially in leadership

positions.7 This is not an issue specific to architecture, implementing policies to support women will

happen on a profession by profession case. Thus, this study is relevant to architecture, especially given

that historically women were not included the profession.

One of the greatest frustrations on the topic of women in architecture is that we don’t know

why women leave. The research being done focuses on understanding why women leave architecture

which can reveal other issues that affect women, especially how women and men are differently

affected by issues like having children. Three groups: The Missing 32% , The Architect’s Journal , and

Parlour have created and distributed surveys on equity or specifically women in architecture. From

analysis of these three surveys, the areas that need to be researched in more depth can be determined.

The question of why women leave architecture is important not just to women who are currently

practicing or studying architecture. It is important because the issues that affect women also affect

men. If we can make improvements in the profession that makes it more appealing to and supportive of

women, it will be more appealing to and supportive of all people. Diversity is important for success in

any endeavor, and women are a necessary factor in that equation. According to a report by McKinsey &

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 4/31

Cozy Hannula

3

Company, “statistically significant studies show that companies with a higher proportion of women on

their management committees are also the companies that have the best performance.”8 Diversity is

always good because more diverse people bring more diverse ideas to the table. In addition, people

tend to mentor those similar to them, therefore people tend to mentor those of their same gender.

Since there are fewer women in leadership, there are fewer mentors for young women professionals.9

This thesis examines the research being done concerning women in architecture through

surveys and proposes a new survey that improves upon the previous ones, trying to understand why

women leave architecture, where they go, and what other factors influence women.

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 5/31

Cozy Hannula

4

Chapter 1: History of Women in Architecture

Women have come a long way since the 1850s, when architectural practice began to take the

structure it currently retains. At that time, women were not widely accepted as architects because the

working conditions were considered to be unfit for a woman. Those who did find work in architecture

were considered exceptional.10 As a result, women often worked in areas that were neglected by men

in the profession, especially focusing on domestic or interior architecture where they could be design for

other women.11 Many women contributed to architecture without participating as architects: writing

about architecture in books and magazines, becoming planners, advocating for housing reform, and

creating domestic manuals that aided women in the design and care of their own homes. 12 Notably,

Harriet Beecher Stowe and Catherine Beecher who wrote The American Woman’s Home in 1869.13

Women found work in the traditional profession as well, and in 1888, Louise Blanchard Bethune became

the first woman to work as a professional architect. The first firm founded by women was Schenk +

Mead in 1918. Shortly after that, in 1921, the Chicago Drafting Club was formed. This later became the

Woman’s Architectural Club, the first organization of practicing women architects. In 1993, Susan

Maxman became the first female president of the American Institute of Architecture (AIA).14

It was not until 1871 that women were first admitted into architecture schools at the University

of Illinois, Syracuse University, and Cornell University, and in 1873, Mary L. Page became the first

woman to graduate with a degree in architecture.15 By 1910, 40 years later, only 50% of schools were

admitting female students.16 It took a while for the profession to recognize the value of including

women in design schools and many public schools discouraged women from attending and several

private schools denied women entrance all together. As a result, the Cambridge School of Architecture

and Landscape Architecture was founded in 1915, the first, and only, school of architecture only for

women.17

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 6/31

Cozy Hannula

5

Those who worked as architects often went unrecognized especially if you look at awards given

in architecture. In 1991, Robert Venturi won the Pritzker Prize, however, his wife Denise Scott Brown

who was his partner and a significant contributor to the work, was not recognized in the award. A

petition to retroactively honor her for the award was signed by many professionals including Venturi,

but it was rejected by the jury of the Pritzker Prize because they are not able to amend an award given

by a different group of jurors.18 To date, two women have won the Pritzker Prize: Zaha Hadid in 2004

and Kazuyo Sejima in 2010.19 In addition, the AIA Gold Medal honoring lifetime achievements in

architecture was posthumously awarded to Julia Morgan in 2014. She is the first, and to date, only,

woman to have won this prize.20 Women have fought to be recognized for their efforts as architects and

are just now starting to be recognized as equals in the profession.

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 7/31

Cozy Hannula

6

Chapter 2: The Surveys

This research on the sociology of why women leave architecture is still in its early stages and

most of the research that has been carried out has been done through surveys, likely because they are

easy to conduct and can reach a wide audience quickly. There are a few studies examining women’s

place in the profession using other methods, but they were done 10 to 20 years ago, when the

profession was much different. Other research that has been done recognizes women who did excellent

work that was overlooked or not attributed to them during their careers. 21 For instance the

International Archive of Women in Architecture was founded in 1985 to “document the history of

women’s contributions to the built environment.”22

The most current research has been done through

surveys and thus they are the focus of this thesis. Three surveys have been chosen for analysis, these

are the most in depth, most recent, and most well-known (See Figure 2 for a comparison of the three

surveys). There are other potential ways to research women in architecture. Possibilities include an

ethnography where observation would yield insight on women’s place in the profession, but a survey is

the easiest way to gather feedback from those with architecture degrees who pursue other paths, and

to explore how the definition of work in architecture may need to be expanded beyond the typical path

of working in an architectural firm and becoming licensed.

Figure 2

Created by author

Basic information about the three case study

surveys for comparison

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 8/31

Cozy Hannula

7

The first survey chosen for analysis is published by the Missing 32% in 2014. The Missing 32% is

a group working toward equity in the profession of architecture; its survey on equity specifically

addressed the question of why women leave architecture. The focus is primarily in the San Francisco

Bay Area, though participants came from other parts of the United States as well. The project is planned

to be expanded across the country in the near future. This is the only survey on this topic that

specifically looks for trends in the United States, and includes topics other than reasons women leave

architecture, but also job satisfaction, hiring and promotion, pay, and educational/professional

experience.23 The survey was chosen because it is the survey of women in architecture with the most

respondents and the most questions in the United States; it is also commonly referenced, so it’s

important to understand the limitations of the data it presents. In addition, it looks at more qualitative

information which is not always easy to survey, and the way it deals with topics like job satisfaction can

be utilized to understand other more opinion-based information.

The “Annual Women in Architecture Survey” done by Architects Journal ( AJ) is the second survey

chosen for analysis. This is one of the first surveys to be done on women in architecture, starting in

2012 and also done in 2013 - 2015. Architects Journal is based in the UK, so the majority of participants

in this survey are from the UK. This is one of the only surveys to be done annually, and was chosen for

its ability to compare data over time. It also looks at perceptions of the profession, including pay,

discrimination, and childcare. Though slightly less comprehensive than the other surveys, it allows

insight into change over time. However, there are some limitations based on its distribution.24

The final survey is “Equity and Diversity in the Australian Architecture Profession: Women,

Work, and Leadership,” produced by a group that is looking into equity in the architectural profession

specifically in Australia. It was funded by the Australian Research Council and partnered with the

Australian Institute of Architects, Architecture Media, BVN Architecture, Bates Smart, and PTW

Architects.25 It is the most comprehensive and thorough survey that has been done on women in

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 9/31

Cozy Hannula

8

architecture. It included the most category options for each question, and included more questions per

topic than the other surveys. Both of these elements allow for more nuanced data. The survey was

done in 2012-2013 and includes separate studies (though with the same questions) for men and

women. Particularly successful is the way it paired numerical data with information that is harder to

quantify. It gathered quantitative data through multiple choice questions and more interpretive data

through open-ended questions. The way these two are combined, and the depth of the information this

survey gathered make it a valuable tool for analysis.26

While all of these surveys are excellent research tools, they all have limitations in what they

were able to find to understand issues facing women in architecture. By looking at what the surveys are

effective for, and what they are less powerful at, a new survey can be developed that expands on the

research that has been done. Each of these case studies has respondents that are from different

locations so it is important to keep in mind when comparing the data that there are cultural and

geographical differences between the three places, as well as differences in the way the architectural

profession is structured. The surveys are being analyzed in the following two categories: Content and

Questions, Survey Format and Distribution, and Data Analysis.

“Annual Women in Architecture Survey” 2012-2015 by Architects Journal

Content and Questions

The AJ survey starts with gathering basic demographic information: profession, location,

experience level, and gender. This was the least comprehensive survey in terms of what was covered

and really is a base level for what surveys on this topic should cover. The Topics are “Discrimination,

Pay, Childcare, Students, and International.”27 This survey looks only at the most common issues cited

as being difficult for women architects, and does not look in depth into finding other potential reasons.

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 10/31

Cozy Hannula

9

AJ studies the perceptions of women in architecture by asking what men and women think

about various issues. Questions in this area include “Has the building industry fully accepted the

authority of the female architect,” and “Do you think having children puts women at a disadvantage in

architecture?”28 This allows us to understand how men and women perceive issues in architecture

which can help us understand why some women might chose a path other than architecture. For

instance, 63% of men and 87% of women surveyed think that having children puts women at a

disadvantage29 and as a result, women may tend to leave the workforce or hold themselves back from

attempting to get promotions if they have children or plan to have children soon because they feel as

though it will impact their career. In addition women may choose to not have children or delay having

children in fear of the potential impact.30 Although it is important to note this method only keeps track

of perceptions, not necessarily reasons women leave architecture.

The most interesting and informative part of AJ survey is the treatment of questions about how

men and women have altered their work habits after having children. It asks architect mothers and

fathers what happened in their career after having children, whether they worked the same number of

hours at the same job, worked fewer hours, got a promotion, changed roles, left their job for more

flexible hours, set up their own practice, or left architecture altogether.31 Many options are provided,

and it allows an understanding of how having children differently affected the women and men who

took the survey. 67.3% of men returned to the same job at the same number of hours but only 32.1% of

women did so. Alternatively 42.2% of women reduced hours at their same job compared to 13.5% of

men. This suggests that, in the UK, having children impacts the hours worked by women more than

those worked by men; spending less time at work likely has a direct impact on their career.

Unfortunately, the answers provided are not mutually exclusive and should have been split into a couple

of questions. For instance, “receiving a promotion” was one choice, as was “going back to the same job”

and working the same hours.32 However it is possible for both of these things could be true for the same

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 11/31

Cozy Hannula

10

person and some responses could be excluded from either category as a result. Another solution would

be to offer a select all that apply option for this type of question.

In general this survey asks leading and ambiguous questions which makes the information more

difficult to interpret and use. One example of a leading question is “Do you think having children puts

women at a disadvantage in architecture?” with the answer options being either “yes” or “no.”33

Putting disadvantage in the question implies that the survey is trying to figure out if there is a

disadvantage, rather than understanding the impact of having children. This implies to the participant

that the researcher believes there may be a disadvantage and could affect how the respondent answers.

A more neutral phrasing of the question would be: “How does having children affect the career of

women in architecture?” and the answer choices would then be “gives an advantage, gives a

disadvantage, or has no effect.” An instance of ambiguity is the questions about discrimination. They

are vague and hard to draw conclusions from. Asking “have you suffered sexual discrimination” and

“have you been bullied during your career in architecture” is inprecise unless sexual discrimination and

bullying are defined because to different people, different actions may fall under these categories.

Better to list categories that the researcher wants to find out about and include “other” as a category to

truly be able to identify workplace discrimination.

Format and Distribution

The AJ Survey is an online survey that is done every year on the magazine’s website. The first

year only women were surveyed, but in following years both men and women were surveyed.34 The

survey is not distributed to firms by Architect’s Journal, but is only taken by those who stumble upon it

or receive the link from peers. Most of the people taking the survey will likely be subscribers to the

journal or people interested in the topic of women in architecture, which is not a representative sample

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 12/31

Cozy Hannula

11

of architects. All answers must be viewed in that lens. Any data listed is a percentage of survey

participants and while it provides insight, the statistics may not hold true for the profession overall.

Data Analysis

The data included and its presentation change from year to year. The categories remain, but

individual questions and which data is published in the journal may change over time, which makes it

hard to truly compare the data over time. However, for questions that remain the same, like salary,

trends start to be seen on what is improving or getting worse.

“Equity in Architecture Survey” 2014 by The Missing 32% Project

Content and Questions

The categories surveyed by the Missing 32% were “Demographics, Licensure, Hiring,

Professional Development, Promotion, Retention, Work-Life Flexibility, and Job Satisfaction.”35 The

Missing 32% Survey handles the job satisfaction and growth and development categories particularly

well. Job satisfaction is particularly hard to quantify, so the survey found information on several

different aspects that influence job satisfaction to begin to make comparisons between men and

women. This is important to women in architecture because if women overall are less satisfied as

architects, that is a very clear reason women may leave the profession. They created criteria that

established job satisfaction and found that being a partner or principal, believing their “firm has an

effective promotion process”, and having “day to day work [align] with career goals” were the top

factors that led to job satisfaction.36 This adds to the job satisfaction data that states that 41% of men

are satisfied at work while only 28% of women are. Now not only is it clear that women are less

satisfied, but firms can be analyzed based on the criteria established by the corresponding question.

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 13/31

Cozy Hannula

12

Another category the Missing 32% treats particularly well is caregiving. Instead of just understanding

whether a respondent has children, they break down their caregiver situation with the categories:

“primary caregiver [with] reduced hours, spouse is primary caregiver, shared duties, employ caregiver,

extended f amily caregiver, school aged children, and adult children.”37 Similar categories are

established for what the survey labels challenges of “work-life flexibility” that could be asked of parents

to understand whether they had to for instance, leave a position, travel less often, or turn down a

promotion because of children.38 How the careers of men and women are affected by becoming a

parent could reveal potential reforms necessary in the profession to either help retain women, or to

make working as a parent easier.

The Missing 32% includes job title and firm leadership in their survey which is necessary to

understanding how women are progressing up the professional ladder. It is important for women to

hold leadership positions in firms because, as discussed earlier, diversity in a firm’s leadership leads to a

successful company.39 Finally, the Missing 32% addresses why women leave architecture, but that will

be addressed later as a comparison between the different surveys.

Format and Distribution.

The Missing 32% survey was an online survey similar to the AJ one in terms of its distribution and the

implications of that. There is a disclaimer at the beginning that notes that this survey is not a cross

section of the profession. Those who took the survey either had the survey sent to them by a friend, or

stumbled upon it so people who took the survey are likely to be interested in the topic of women in

architecture, and the results may be inaccurate for that reason.40 Therefore the results cited in the

Missing 32% are not necessarily true of the profession.

Data Analysis

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 14/31

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 15/31

Cozy Hannula

14

have left the profession have a master’s degree, or have worked in other fields, or work in architecture,

but in a secondary role, etc.

Parlour included one category that was not looked at by any other survey but is interesting topic

to consider and could be revealing of work-life balance: professional engagement. This included a series

of questions of participation in architectural events outside of work: current or previous membership in

the Australian Institute of Architects or professional organizations in architecture-related fields,

participation in awards programs and events, participation with architectural media, e.g. writing for

blogs or journals or speaking about architecture on television or radio.44 Parlour also looks at the

workplace in great depth: size of firms, flexible working options, number of previous jobs, duration of

employment, and position among many other factors.45 This is another interesting topic because of the

potential impact of working environment on whether people leave architecture, particularly concerning

the availability of flexible working conditions.

Interestingly Parlour does not include any questions about family or childcare. This seems

unusual because most studies find that having children affects the careers of all people but especially

women. It is understandable to not make family and childcare a main focus of the survey, but to

entirely leave it off seems like it misses out on an important subject that affects equity in architecture.

They do include “care for children” as an option for two questions asking why a participant took a break

from their studies and asking why they took a break from their career, but, the overall data about how

many had children is missing. If more women than men drop out of the work force, take a break in their

careers, or cut back hours due to having children, policy can be created to better accommodate that.

Format and Distribution

The Parlour survey, like the Missing 32% Survey, has a disclaimer that it is not surveying a

representative sample and that must be considered when understanding the results. However they did

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 16/31

Cozy Hannula

15

take steps to make sure it would reach people who weren’t connected to their website by distributing it

through their research partners which included several schools and a few architecture practices, as well

as by advertising it on many architecture websites and in newsletters of architectural organizations.

Overall the method of distribution was the best possible way to reach a diverse group without having a

representative sample. In addition, they separated the survey into two separate surveys: one for men

to take and one for women to take, though both have the same questions.

Data Analysis

The survey is a little lengthy and the results list all the collected data that can be difficult to sort

through, but they also provided a document that pulled certain data out of both surveys so they could

be compared and to help make conclusions. That piece also included a written portion with their main

findings which helped pinpoint the important parts of the data.46

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 17/31

Cozy Hannula

16

Chapter 3: Survey Improvements

Survey Improvements: Content and Questions

Typically, articles about women in architecture focus on pay, childcare, and discrimination,

which are the topics that people generally assume are reasons women leave architecture more often

than men. And while these certainly play a part, these are only the beginning of reasons women leave

architecture. The reasons women leave architecture are more nuanced, varied and complicated than

can ever be truly analyzed, but it is necessary to look at more than just those big three in order to

understand this issue and ensure that no information is mission.

The most valuable questions to understand this topic ask why people have left architecture. The

way these questions are positioned and analyzed is the most important part of a survey. First it is

necessary to compare the answers of men to those of women to understand whether certain reasons

are cited more often for women. In addition, the phrasing of the answers is very important. Leaving the

profession permanently should be separated from taking a leave of absence. There could be pre-

determined categories for why people leave, or they may write-in an answer, or some kind of

combination. The tricky thing about providing categories is that the reasons survey writers have chosen

may influence what people report, but the hard part of answers written in is they come in a wide variety

and can be hard to categorize into meaningful answers. The necessary precision of this question can be

shown by comparing the Missing 32% with the Parlour Survey. The categories provided by the Missing

32% are “low pay, long hours, no opportunity for promotion, lack of role models, and unprofessional

behavior and bullying.”47 Parlour lists “better renumeration, less overtime, more flexible hours, further

professional challenges, to pursue social objectives, to secure greater control over the outcome, and

other.”48 Those are very different categories between the two surveys. The Missing 32% only includes

things that are bad about the profession when people may choose to leave for personal reasons or

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 18/31

Cozy Hannula

17

because a different job appeals to them more, or for numerous other reasons, or more likely, a

combination of reasons. This may be a question that is better answered by ranking listed categories to

account for the wide range of possible answers.

Another important part of this information is understanding where people go when leaving

architecture. It is looked at in the Missing 32% Survey but the data is only presented for women, and it

looks at professions women go into if they are leaving architecture. This is interesting because what if

women are not “leaving architecture” but expanding what an architecture degree means. Maybe

women go into other design fields or fields connected to architecture, e.g., construction, real estate, or

interior design. Knowing what is drawing women away from architecture, and why they chose these

fields can help us understand what the profession can do to retain women. Maybe the loss of women

after graduation is not something that can be fixed by changing the profession of architecture but can

be done by expanding the definition of architecture. One of the biggest challenges of understanding

how many women are utilizing their degrees in architecture is knowing what is included in that

definition. Just because women are not licensed architects, or choose not to follow the traditional path

does not mean they are not contributing to architecture or that they are not utilizing their degrees.

Therefore it is important to ask, as the Parlour survey does: “Do you feel you use your architectural

background in your current role?”

There are some things that may affect the amount of women who end up leaving the profession

that are not currently addressed in surveys but maybe should be in order to fully understand why

women drop out. The most important one is hiring practices and what is happening not just within the

profession, but also in the time between graduation and entering the profession. Are women more

easily discouraged from continuing to search for architecture jobs as men? Do men and women go on

the same number of interviews, on average, before being hired? Are women more likely than men to

explore and apply to job options outside of just architecture?

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 19/31

Cozy Hannula

18

Survey Improvements: Format and Distribution

One of the hardest part of these surveys is reaching a representative sample. There are

situations that are not represented simply because there are people who are not reached by traditional

distribution of these surveys through architectural channels. This is improved when, like in the Parlour

survey, universities can reach out to architecture alumni. All of the surveys used as case studies are

cross-sectional surveys, which are excellent to research information at one point in time, but they are

less useful in determining causal relationships. A longitudinal survey asks the same group of questions

to the same participants at intervals over a long period of time and makes conclusions based on that. In

this case, a longitudinal survey would be particularly advantageous. The survey would start with a pool

of graduating individuals, ideally from different universities, and follow their progression into their

career and would continue even if they did not pursue architecture. This would make finding people

who previously had degrees in architecture but had since left the profession very easy because they

would be automatically included in the sample of people who had graduated. Another benefit to the

longitudinal survey in this case is it corrects for generational differences in the economy. For instance,

people sometimes leave the profession due to layoffs or lack of work. A longitudinal survey can better

control for variables outside the profession of architecture because the same factors will affect all

survey respondents equally.

Survey Improvements: Data Analysis

It is necessary to view the data separated by gender to understand how gender affects each

issue. There are other interesting ways to group the data, seeing how certain categories like

organization structure differ between those who are in architecture and those who have left

architecture. Or how different aspects, like hours worked and salary, vary based on both gender and

position.

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 20/31

Cozy Hannula

19

Chapter 4: Longitudinal Survey

This survey looks to improve and expand upon the previous surveys. Chosen by pulling certain

questions from each of the example surveys, the new survey includes questions about Professional

Background and Hiring, Organization Structure, Family, and Professional Activities Outside of Work. It is

fairly short in order to keep it simple and focused on these specific issues, ones that had interesting data

from the case studies and would be beneficial to have more data on from a different sample group.

There are also questions where you pick all of the answers which apply to you (for example, why did you

leave architecture) and then rank those choices in order of how influential they were. This allows for

more nuanced data about why people leave the profession, the most difficult question on which to

gather data. Second, it is longitudinal in nature and will be distributed in a way that helps get a

representative sample of people involved with architecture. Six universities will be approached with the

survey, two private schools, two public schools, and two public schools offering a B. Arch Program. The

various schools should be from different geographical areas to help eliminate confounding variables.

The survey would be distributed to one graduating class and follow that class. The survey will be

distributed via email and each participant will retake the survey every three years because that will

capture many of the pinch points established by the Missing 32% survey, as shown in Figure 3.49

Figure 3

Created by author

Career Pinch Points as found by the Missing 32% happen

approximately every 3-6 years. Here they are lined up with

the percentages of women who are at those points in their

career.

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 21/31

Cozy Hannula

20

Architecture Graduate Longitudinal Survey

1. Which gender do you identify with?

Male

Female

Other (please describe)

Prefer Not To Answer

2.

What is your current employment status?

Employed in Architecture option 1

Employed in a field related to architecture (please specify) option 2

Employed in a field unrelated to architecture (please specify) option 3

Unemployed option 4

Other (please describe) option 5

2.1 (if option 1) What drew you to the architectural profession?

Write in answer

2.2 (If option 2 or 3) Do you believe you utilize your architecture degree in your work?

Yes

No

2.1A (if yes) How?

Write in answer

2.3 (if option 2, 3, or 4) Do you consider yourself to have ‘left’ architecture

Yes

No

2.3A (if yes) What is your reason for leaving architecture? Choose all that apply

Compensation

Desire for fewer hours

Desire for more flexible hours

Desire for more hours

Desire for a different role/position

No opportunity for promotion Unprofessional behavior/bullying

Take care of children

Take care of family member

Health

Desire to travel less for work

Other (please specify)

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 22/31

Cozy Hannula

21

Please rank your choices in order of how much each reason influenced your

decision

e.g. 1. (most) Remuneration

2. Desire for more flexible hours

3. (least) No opportunity for promotion

2.3B(if yes) Do you intend to return to architecture in the future?

Yes

No

2.4 (if option 1) What is your current position?

Partner or Principal

Other Leadership Position

Licensed Architect

Designer or Intern

Sole Practitioner

Other (please specify)

2.5 (if option 1) What is the highest position you wish to hold?

Partner or Principal

Other Leadership Position

Licensed Architect

Designer or Intern

Sole Practitioner Other (please specify)

3. How many years have you worked at your current organization?

0-2

2.1-5

5.1-10

>10

4. How many people, including yourself, work in your organization?

Write in answer

5. How many jobs did you apply to before being hired for your current job?

Write in answer

6. How many interviews did you receive before being hired for your current job?

Write in answer

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 23/31

Cozy Hannula

22

7. Does your place of employment offer any of the following flexible working options (outside of a

traditional 9-5 job)? – mark all that apply

Same number of hours, but irregular hours (evenings and weekends)

Adjustable start and finish times

Working remotely Self Employed – Set own hours

Other (please specify)

8. What is your current salary?

under $30,000

$30,000 – 50,000

$51,000 – 70,000

$71,000 – 90,000

$91,000 – 110,000

Over $110,000

9. How many architectural organizations have you worked at including your current job?

0

1-2

3-4

5-6

7-8

8-10

11 +

10.

Are you licensed in architecture? Yes

No

In process

10.1 (if in process) How far along are you in IDP

0-25%

26-50%

51-75%

76-100%

10.2 (if in progress) How many Architectural Record Examinations have you completed?

0

1

2

3

4

5

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 24/31

Cozy Hannula

23

6

7

10.3 (if licensure isn’t in process) Do you intend to pursue licensure in the future?

Yes

No

10.3A (if no) Why?

Write in answer

11. Do you have children?

Yes

No

11.1 (if yes) Caregiver Situation (choose all that apply )

Primary caregiver Spouse is primary caregiver

Shared duties

Employ caregiver

Extended family is caregiver for children

School age children

Adult children

Other

12.

How many hours do you work on average per week?

0-10

10.1-20

20.1-30

30.1-40

40.1-50

50.1-60

70 +

13. How many hours would you ideally work on average per week?

0-10

10.1-20

20.1-30

30.1-40

40.1-50

50.1-60

70 +

14. Would you consider yourself to be…

Full time

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 25/31

Cozy Hannula

24

Part time

Unemployed

Other

15. How often do you engage in professional events outside of work (e.g., awards programs,

conferences, meetings for professional organizations)? Never

Rarely (one or more times per year)

Occasionally (one or more times per month)

Often (one or more times per week)

16. Do you belong to at least one professional organization?

Yes

No

17.

Do you belong to one or more architectural professional organizations?

Yes

No

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 26/31

Cozy Hannula

25

Conclusion

The current research understanding why women leave the profession and the surrounding

issues is mainly done through surveys because of the capability to reach those who used to work in

architecture, but no longer do. After an analysis of the three most well-known surveys, a longitudinal

survey was created that would help overcome some of the limitations of the current surveys. The

longitudinal study would help gather a more representative sample of the profession because it would

be distributed to an entire graduating class instead of being distributed to and taken by principally

groups of people already interested in the topic of women in architecture. The survey improves the

questions asked by using best types of questions from all three surveys and adding the new content

category of hiring practices. The survey would be distributed to diverse universities in order to gather

data from participants with diverse educational backgrounds. This survey would have a small number of

universities, only six, and a later study could be expanded to include more universities. The survey only

includes universities in the United States, as different geographical locations have different ways of

structuring the profession, and the research could be expanded in the future by applying the model to a

different geographical location.

41% of architecture students are women, but only 25% of the profession is women. If diversity

is truly to be achieved in the profession of architecture, there needs to be support for women architects

so they enjoy being a part of this profession and can contribute and advance to leadership positions. It

is impossible to understand how to best support women and allow them to participate in the profession

until we understand what draws women away from architecture and why if we are ever going to be able

to improve conditions for women. Improving conditions for women, and putting in place policies that

make it more possible and enjoyable for women to remain in the profession, will be positive for all

people working in architecture.

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 27/31

Cozy Hannula

26

Notes

1 "‘Ladies (and Gents) Who Lunch with Architect Barbie’ Event," ArchDaily, last modified October 13, 2011,

http://www.archdaily.com/?p=175512.

2

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, and Integrated PostsecondaryEducation Data System (IPEDS), “Digest of Education Statistics,” Fall 2012,

http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_318.30.asp?current=yes.

3 Bureau of Labor Statistics, Household Data Annual Averages, (2014), http://www.bls.gov/cps/

cpsaat11.pdf.

Lian Chikako Chang, “Where are the Women: Measuring Progress on Gender in Architecture,”

Association of Collegiate Schools in Architecture, accessed October, 09 2014, http://www.acsa-

arch.org/resources/data-resources/women.

Barbara Porada, "The Scott Brown Petition & Women’s Role in Architecture," ArchDaily,

http://www.archdaily.com/?p=371487.

6 Sheryl Sandburg, Lean in: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead (New York: Knopf, 2013).

7 Georges Desvaux and others, “Women Matter: Gender Diversity, a Corporate Performance Driver,”

McKinsey & Company, 2007). file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/

Women_matter_oct2007_english.pdf.

8 Georges Desvaux and others, “Women Matter.”

Amy Kalar, “Establishing the Business Case for Women in Architecture,” (Presentation, American

Institute of Architects Minnesota Convention, Minneapolis, MN, November 11, 2014).

10 Wright, “On the Fringe,” 291, 284-285

11 Gwendolyn Wright, “On the Fringe of the Profession: Women in American Architecture,” in The

Architect: Chapters in the History of the Profession, ed. Spiro Kostoff. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997),

280-281.

12 Wright, “On the Fringe,” 284-285

13 Megan Jett, "Infographic: Women in Architecture," ArchDaily, http://www.archdaily.com/?p=216844.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Wright, “On the Fringe,” 291

18 Porada, “The Scott Brown Petition.”

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 28/31

Cozy Hannula

27

19 Jett, “Infographic: Women in Architecture.”

20 Ibid.

Despina Stratigakos, “Building on the Past, A History of Women in Architecture,” Beverly Willis

Architecture Foundation, http://bwaf.org/building-on-the-past-a-history-of-women-in-architecture/.

22“International Archive of Women in Architecture,” IAWA, last modified April 9, 2015,

http://spec.lib.vt.edu/iawa/.

23 The Missing 32 Percent, “Equity in Architecture Survey 2014,” http://themissing32percent.com/.

24 Laura Mark, “Women in Architecture, 2015,” Architect’s Journal 241, no. 3 (January 23, 2015): 22-37.

25 Justine Clark and others, “Technical Report and Preliminary Statistics: Where do All the Women Go?”

Parlour, http://archiparlour.org/submissions-and-reports/

26 Clark and others, “Where do all the Women Go?”

27 Laura Mark. “Women in Architecture Survey 2014.” Architect’s Journal 239, no. 1 (2014): 28.

28 Ibid., 29, 33.

29 Ibid., 33.

30 Sheryl Sandburg, Lean in: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead (New York: Knopf, 2013).

31 Mark, “Women in Architecture Survey 2014,” 33.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Richard Waite and Ann-Marie Corvin, “Shock Survey Results as the AJ Launches Campaign to Raise

Women Architect’s Status,” Architects’ Journal 235, no. 1 (January 12, 2012): 5,

http://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/daily-news/shock-survey-results-as-the-aj-launches-campaign-to-raise-

women-architects-status/8624748.article.

35 The Missing 32 Percent, “Equity in Architecture.”

36 Ibid.

37 The Missing 32 Percent, “Equity in Architecture.”

38 Ibid.

39 Georges Desvaux and others, “Women Matter.”

40 The Missing 32 Percent, “Equity in Architecture.”

41 Ibid.

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 29/31

Cozy Hannula

28

42 Clark and others, “Where do all the Women Go?” 15.

43 Ibid., 12-20.

44 Ibid., 34-29.

45 Ibid., 29-35.

46 Ibid., 2.

47 The Missing 32 Percent, “Equity in Architecture.”

48 Clark and others, “Where do all the Women Go?” 39.

49 The Missing 32 Percent, “Equity in Architecture.”

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 30/31

Bibliography

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Household Data Annual Averages. (2014). http://www.bls.gov/cps/

cpsaat11.pdf

Chang, Lian Chikako. “Where are the Women: Measuring Progress on Gender in Architecture.”

Association of Collegiate Schools in Architecture. Accessed October, 09 2014. http://www.acsa-

arch.org/resources/data-resources/women.

Clark, Justine, Amanda Roan, Naomi Stead, Karen Burns, Gilian Whitehouse, Gill Matthewson, Julie

Willis, and Sandra Kaji-O’Grady. “Technical Report and Preliminary Statistics: Where do All the

Women Go?” “Technical Report and Preliminary Statistics: And What About the Men?” Parlour.

http://archiparlour.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Technical-Report_And-What-About-the-

Men_Upload.pdf

Clark, Justine, Amanda Roan, Naomi Stead, Karen Burns, Gilian Whitehouse, Gill Matthewson, Julie

Willis, and Sandra Kaji-O’Grady. “Technical Report and Preliminary Statistics: Where do All theWomen Go?” Parlour. http://archiparlour.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Technical-

Report_Where-do-all-the-Women-go_Upload.pdf

Clark, Justine, ed. “Parlour: Women, Equity, Architecture.” Archiparlour.org

de Graft Johnson, Ann, Sandra Manley, and Clara Greed. “Why Do Women Leave Architecture?”

University of the West England. (2003).

Desvaux, Georges, Sandrine Devillard-Hoellinger and Pascal Baumgarten. “Women Matter: Gender

Diversity, a Corporate Performance Driver.” McKinsey & Company. (2007).

file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/Women_matter_oct2007_english.pdf.

“International Archive of Women in Architecture.” IAWA. Last modified April 9, 2015.

http://spec.lib.vt.edu/iawa/.

Jett, Megan. "Infographic: Women in Architecture." ArchDaily. http://www.archdaily.com/?p=216844.

Kalar, Amy. “Establishing the Business Case for Women in Architecture.” Presentation at the American

Institute of Architects - Minnesota Convention, Minneapolis, MN, November 11, 2014.

"‘Ladies (and Gents) Who Lunch with Architect Barbie’ Event." ArchDaily. Last modified October 13,

2011. http://www.archdaily.com/?p=175512.

Mark, Laura. “Women in Architecture Survey 2014.” Architect’s Journal 239, no. 1 (2014): 28-37.

Mark, Laura, “Women in Architecture, 2015.” Architect’s Journal 241, no. 3 (January 23, 2015): 22-37.

M., L. “AJ Survey Reveals Rise in Workplace Sex Discrimination.” Architect’s Journal 241, no. 3 (January

23, 2015): 4-5.

7/25/2019 Cozy Hannula_Second Draft Final

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cozy-hannulasecond-draft-final 31/31

Cozy Hannula

Sandberg, Sheryl. Lean in: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead . New York: Knopf, 2013.

Stratigakos, Despina. “Building on the Past, A History of Women in Architecture.” Beverly Willis

Architecture Foundation. http://bwaf.org/building-on-the-past-a-history-of-women-in-

architecture/.

The Missing 32 Percent. “Equity by Design: The Missing 32% Project.” themissing32percent.com.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, and Integrated Postsecondary

Education Data System (IPEDS). “Digest of Education Statistics.” Fall 2012.

http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_318.30.asp?current=yes

Porada, Barbara. "The Scott Brown Petition & Women’s Role in Architecture." ArchDaily.

http://www.archdaily.com/?p=371487

Waite, Richard and Ann-Marie Corvin. “Shock Survey Results as the AJ Launches Campaign to Raise

Women Architect’s Status.” Architects’ Journal 235, no. 1 (January 12, 2012): 5.

http://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/daily-news/shock-survey-results-as-the-aj-launches-campaign-to-raise-women-architects-status/8624748.article.

Wright, Gwendolyn. “On the Fringe of the Profession: Women in American Architecture.” In The

Architect: Chapters in the History of the Profession, edited by Spiro Kostoff. 280 – 390. New York:

Oxford University Press, 1997.