Constructing Sustainable Rural Landscapes: Oil Mallees and the Western Australian Wheatbelt

-

Upload

sarah-bell -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

2

Transcript of Constructing Sustainable Rural Landscapes: Oil Mallees and the Western Australian Wheatbelt

194

Geographical Research

•

June 2005

•

43(2):194–208

Constructing Sustainable Rural Landscapes: Oil Mallees and the Western Australian Wheatbelt

SARAH BELL,

University College London, England

Abstract

This paper considers the landscapes of the Western Australian wheatbelt and thepossibilities for sustainability signified by the Oil Mallee Project. The Oil Mal-lee Project aims to develop commercially viable tree crops for the low rainfallwheatbelt region as a means of profitably managing dryland salinity. Interviewswith farmers and other stakeholders in the Oil Mallee Project and agriculture areanalysed to reveal important elements of landscape construction in the wheatbeltand stages in the emergence of the Project. These elements include historicalland clearing, international chemical and machinery companies and the technol-ogies they supply, land of marginal economic productivity, global food marketsand alley farming systems. The paper uses material semiotics and actor-networktheory in describing the networks of relationships that shape wheatbelt land-scapes. Breakdowns in the dominant networks of industrial agriculture providespaces for the Oil Mallee Project to build relationships that reconnect industrialsystems to the specific ecology of the wheatbelt landscape. However, thenetworks of industrial agriculture remain powerful and the Project has workedstrategically to become integrated with existing agricultural systems, rather thanaiming to directly resist or entirely displace dominant patterns of production inthe wheatbelt.

KEY WORDS

material semiotics; dryland salinity; actor-network theory; agri-forestry; agri-food networks; sustainability; agriculture

Everything is welded together in a continu-ous steady flow, arrested as it were for a brieftime from its motion. It is a slow, subtle land-scape of softly blended parts — nothing dis-junct, no joins, but gentle fusions.

And superimposed on this is the pattern offarms: where enough of the vegetation is leftto reveal the old rhythm even the paddocks,the homesteads and the mobs of sheep flowinto it, are integrated and folded into thebasic structure, so that the posts of fencelinesbecome the knots tying man’s (

sic

) artifacts(

sic

) back into the underlying pattern of theearth. (York Main, 1971, 27)

Introduction

Naturalist writer Barbara York Main’s vision ofthe Western Australian wheatbelt in the early

1970s was a place where the artefactual net-works of agriculture fused seamlessly with theancient form of the land. The patterns imposedby non-indigenous people and their fence linesoverlay the ancient patterns of the land to createa novel, hybrid space. This is a vision of ruralsustainability, where the structures of agricultureand human settlement are formed throughinterplay with the rhythms and patterns of theunderlying earth. The patterns of modern agri-cultural production are shaped in relationshipwith the locally specific form and ecology of thelandscape.

The Western Australian wheatbelt has changedmuch since the early 1970s. Three short decadesleading to the close of the second millenniumseem but a brief moment in the history of theslow, subtle landscapes traditionally owned andmanaged by Nyoongar, Yamitji and Wongi

S. Bell:

Constructing Sustainable Rural Landscapes

195

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

peoples. However, in this time disruptions havebecome apparent in the patterns of relationshipsamongst humans, technology and land, whichcomprise the wheatbelt landscape. The networksof artefacts that comprised the farms York Mainlooked upon are now shaped by agents asdiverse as global food markets, internationalchemical companies, urban voters, demandingconsumers, and satellite-guided machinery. Theancient, fluid patterns of the underlying earthreferred to by Main are now apparent not somuch in the movement of sheep and layout offences, but in the salt rising to the soil surface,poisoning remnant vegetation and threateningproductive land across a third of the region(Ferdowsian

et al.

, 1996).Wheatbelt landscapes are shaped by industrial

agriculture, reinforced by forces of globalisationand a neo-liberal regulatory regime. The sustain-ability of current patterns of relationships thatcomprise these landscapes is increasingly threat-ened in the wheatbelt, as in other rural places.Issues of concern in changing rural landscapesinclude, but are not limited to: the impact ofglobalisation and neo-liberal political ideologies(Gray and Lawrence, 2001); the Landcare move-ment (Lockie and Vanclay, 1997; Lockie, 2001a);agricultural sustainability and food production(Lockie, 2001b; Lockie and Pritchard, 2001);gender relations (Bryant, 2001; Davidson, 2001;Geno, 2001); and access to services (Gerritsen,2000; Collins, 2001). Rural landscapes areshaped not only by the underlying earth, butalso by increasingly dynamic, complex and far-reaching networks of relationships among actorsacross regional, state, sectoral, ecological andcultural boundaries. In concluding a volumedevoted to the changing social, political andecological realities of rural and regionalAustralia, Pritchard and McManus (2000, 219)asserted that

[s]pecific places in rural and regional Aus-tralia are not islands, separate from the restof humanity. Their future rests with the net-works of capital, people, ideas and imagesthat serve to locate them globally.

Rural sustainability requires that the networksthat shape contemporary rural landscapes arereconfigured in ways that enable patterns ofartefacts and people to be reconnected to theunderlying ecology, hydrology, soils, andgeomorphology. Breaks are emerging in thenetworks of industrial agriculture and theirrelationships to specific places, providing new

opportunities for such reconfiguration to takeplace. Ecological degradation caused by inap-propriate agricultural systems, increased eco-nomic pressure on family farmers, social declinein rural communities, and the need for novelresponses to global ecological issues such ashuman-induced climate change and biodiversityloss, provide openings for new relationshipsamongst people, technology and land to emergein rural places such as the wheatbelt.

Sustainability is a contested concept and itsmeaning has been subject to much debate anddeliberation (see for example Jacobs, 1999;Pannell and Schilizzi, 1999; Adams, 2001).Drawing on the insights of actor-network theoryand material semiotics described in this paper,I define sustainability as ordering materialrelationships between humans and non-humansin ways that support ecological integrity andhuman development. Non-humans include tech-nologies, landscapes, and other living species.Ecological integrity implies maintaining thefunction and dynamic form of ecosystems,while recognising the role of humans in ecosys-tems. Human development has several dimen-sions including social, cultural and economicimprovement over time, while recognising theimportance of ecological values and services tohuman well-being. In the context of the casestudy presented in this paper, I propose that theordering of relationships between human andnon-humans for sustainability must begin byreconfiguring the networks of industrial agricul-ture to connect modern artefacts of productionto the ecology of rural landscapes.

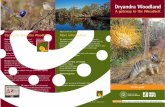

The study area in this paper, the WesternAustralian wheatbelt (Figure 1), is dominatedby industrial agricultural systems. Industrialagriculture uses large, increasingly automated,mechanical equipment to produce food, fibreand energy using large inputs of synthetic chem-icals and fertilisers, often produced at a distancefrom the farm (Berry, 1986; Beus and Dunlap,1990; Goodman and Watts, 1997). This systemof agriculture is usually characterised by mono-culture cropping and intensive livestock produc-tion. These systems utilise varieties of plants andanimals that have been selected and improvedthrough scientific research and development tomaximise production. The products of industrialagriculture are sold into mass markets, whichare dominated by international distribution,processing and retailing corporations. Increas-ingly, industrial agriculture requires farmers toengage in quality assurance, environmental

196

Geographical Research

•

June 2005

•

43(2):194–208

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

management, detailed market analysis and otherfunctions that have their origins in the manage-ment of industrial manufacturing systems.

This paper aims to demonstrate the potentialfor sustainable landscapes through the reconnec-tion of industrial networks of agriculture to theecology of rural places. It analyses particularconfigurations of relationships between humansand non-humans that currently comprise theWestern Australian wheatbelt, in order toidentify opportunities for reconfiguring theserelationships for sustainability. The Oil MalleeProject is used as a case study of how this mightbe achieved.

The paper begins with a brief description ofthe Oil Mallee Project (hereafter called ‘theProject’), the qualitative methods used to collectdata about the Project and Western Australianagriculture, and material semiotics, the method-ology used to develop and analyse the casestudy through attention to material relationships.In order to demonstrate how the Project is

reconnecting artefacts of production with theecology of the landscape, some of the relation-ships that currently shape the wheatbelt aredescribed. These include historical land clear-ing, international agribusiness networks thatdrive farmers’ decision-making, and biophysicalrealities of salinity and low soil fertility in thewheatbelt. The point of this description is tohighlight some of the relationships which shapewheatbelt landscapes, with a view to revealingsome of the weak spots and sites of breakdown orresistance in the networks of agriculture whichthe Project exploits in working towards a moresustainable wheatbelt. The Project does notdirectly resist industrial networks of agriculture,but seeks integration with existing enterprises whileexploiting breakdowns and points of weaknesswithin those networks, including severe landdegradation and declining economic conditionsfor farmers. The paper identifies some of thesesites that provide opportunities for the Projectto begin reconfiguring the wheatbelt towards

Figure 1 The Western Australian wheatbelt region, approximating the area between 270 mm and 750 mm annual rainfall.The shaded area represents the wheatbelt, and the isolines are rainfall isohyets (Source: Beresford et al., 2001, 8).

S. Bell:

Constructing Sustainable Rural Landscapes

197

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

sustainability. Barriers to the integration of oilmallees and industrial agriculture, most signifi-cantly financial constraints, are also recognised,posing hurdles for the Project to overcome.

The Oil Mallee Project

The Project is a new industry developmentwhich demonstrates the possibilities of recon-necting patterns of industrial development withthe ecology of the wheatbelt landscape. TheProject aims to develop seven eucalypt speciesinto agri-forestry tree crops suitable for the low-rainfall conditions of this region, particularlywhere annual rainfall is between 270 and 450 mm(Bartle

et al.

, 1996; Barton, 2000; Black

et al.

,2000; Bell

et al.,

2001; Beresford

et al.

, 2001).The species used in the Project are:

Eucalyptuskochii

subspecies

kochii

and subspecies

plenis-sima; Eucalyptus oleosa

variety

borealis

, renamed

Eucalyptus horistes; Eucalyptus angustissima;Eucalyptus gratiae

;

Eucalyptus loxophleba

subspecies

lissophloia;

and

Eucalyptus poly-bractea

. This will improve management andmitigation of dryland salinity, which is the out-come of rising water tables due to the replace-ment of deep-rooted perennial vegetation withshallow-rooted annual crop and pasture species.The Oil Mallee Project has similarities withother efforts to develop industries based on deep-rooted indigenous vegetation, including the revi-talisation of the sandalwood industry in this region(Tonts and Selwood, 2003), but the Project isnotable for its aim of integrating large-scalerevegetation with broad-scale industrial agri-culture, rather than seeking to exploit nichemarkets for high-value indigenous products.

If fully realised, the Project will enable farm-ers to receive an economic return from plantingnative trees by harvesting the above-ground bio-mass and processing it to produce eucalyptus oil,activated carbon and renewable energy (Stucley,1999). The trees have well-developed roots thatallow them to re-sprout after harvesting, whichcan occur every two to four years over an indef-inite period. The roots of the trees sequester car-bon, providing carbon credits that could betraded by growers under a favourable legislativeregime (Shea, 1998). International trading ofcarbon credits by Australian growers requiresthe Australian government to ratify the KyotoProtocol to the Framework Convention onClimate Change. The Project model includesalley-farming systems, where trees are plantedin rows to allow inter-cropping and grazing,while maximising the salinity benefits of tree

planting. In most alley farming situations, rowsof trees are spaced according to the width ofmachinery to allow manoeuvring of equipmentneeded to continue industrial agricultural enter-prises between the trees. It is envisaged thatmallees will be planted on productive farm land,to provide enough biomass to supply processingplants, while providing an economic return tofarmers that is comparable to existing agricul-tural crops. Local procurement and establish-ment of the seedlings, and biomass processing,create employment in a region suffering theeffects of rural economic restructuring.

The Project began at Murdoch University inthe early 1980s with chemistry researcher AllanBarton’s investigations into potential new usesfor eucalyptus oil and the possibilities for devel-oping a eucalyptus oil industry in Western Aus-tralia. Barton’s work included the selection ofhigh leaf-oil yielding eucalypts from surveys ofremnant vegetation in the south-west of WesternAustralia. In the early 1990s the Department ofConservation and Land Management (CALM)became involved in the Project. The Departmentprovided significant resources and leadership indeveloping the species selected by Barton’sresearch group into a commercial tree crop forlow-rainfall wheatbelt areas. CALM’s work, ledby John Bartle, was motivated by the need tofind commercial tree crop solutions to the man-agement of dryland salinity. CALM also helpedestablish the Oil Mallee Association of growersto ensure strong farmer involvement in the newindustry, and the Oil Mallee Company was laterestablished to further commercial development.In the late 1990s the Western Australian powerutility, Western Power, and a small engineeringfirm, Enecon, became involved in a proposal tobuild an integrated, mallee biomass processingplant at Narrogin, to produce eucalyptus oil,activated carbon and electricity. In 2003, aJapanese power company, Kansai, providedfunds for one million mallees to be planted onwheatbelt farms for carbon sequestration.

Between 1994 and 2003, 27 million malleeswere planted by more than 1000 farmers. TheProject has received significant public sectorinvestment (Wallace, 2001). Despite large-scaleplanting full commercial success is still notassured. Issues remaining to be resolved includetechnical developments in harvesting andprocessing, and the ability to attract fullycommercial, private-sector investment based onviable economic returns.

198

Geographical Research

•

June 2005

•

43(2):194–208

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

Methods

The research reported here was part of a largerproject involving the Oil Mallee Project as acase study of sustainable development. Thelarger project involved semi-structured qualita-tive interviews with people who formed fourbroad categories:

1. key actors in the Oil Mallee Project who arecurrent and former employees of MurdochUniversity, CALM, Western Power and Enecon(five men);

2. employees and representatives of the OilMallee Company and Association (four men,one woman);

3. people with particular interests in sustainableagriculture in Western Australia, includingtwo prominent scientists, a senior agricul-tural economist, a rural social researcher andconsultant, a representative of the WesternAustralian Conservation Council, and re-presentatives of the Wheatbelt AboriginalCorporation (five men, two women), and

4. wheatbelt farmers within 100 km of themajor regional centres of Geraldton andNarrogin (11 men, nine women).

Twenty farmers participated in five group inter-views. Each farmer interview group wascomprised of family members. Three of the fivegroups included two or more generations ofadult farmers from the same family. Of theremaining two groups, one was a couple in theirthirties, and the other was comprised of threecouples in their twenties who shared extendedfamily relationships, but farmed different prop-erties with their parents and siblings. All farmershad planted oil mallees on their properties, moti-vated by land conservation and attracted by thepotential for commercial development of theindustry. Nine women and 11 men participatedin the farmer interview groups, which were heldon the family farm. The nearest large regionalcentre for the farm interviews was either Gerald-ton or Narrogin. The sites near Narrogin werechosen for interviews because of their proximityto the pilot Integrated Processing Plant for oilmallees. The sites near Geraldton were chosenbecause my family origins lie in agriculture inthis district and I had existing relationships withthe interview participants. In contrast to theNarrogin district interview sites, farmers nearGeraldton are distant from any proposedprocessing of oil mallees, despite significantinterest in oil mallee plantings in the surround-ing region.

While the family-farming group structure istypical of wheatbelt farms, the farmers inter-viewed for this study were not chosen to be rep-resentative of all wheatbelt farmers. However,the semi-structured, qualitative interviews pro-vided a rich source of data for in-depth analysisof issues relevant to the sustainability of wheat-belt landscapes. The age structure of the farmerinterview groups provides perspectives fromboth current and future principal farm decision-makers, enabling insight into future possibilitiesas well as current and historical conditions andperspectives of farmers in the wheatbelt.

The interview structure and questions variedaccording to the role or interest of the interviewparticipants in the Oil Mallee Project. All theinterviews covered three main topics:

1. personal experiences and family history inthe wheatbelt;

2. knowledge and perspectives on the Oil MalleeProject, including analysis of its strengths,weaknesses, threats and opportunities, and

3. visions and predictions for the future ofagriculture in Western Australia.

Three women and 14 men, who were from thenon-farmer participant categories, were inter-viewed individually in their workplaces. Indi-vidual interviews were of approximately45 minutes duration, and group interviews typi-cally took two hours. All interviews were taped andtranscribed verbatim. Scientific, media, legal,policy and other documents covering the first 20years of the Oil Mallee Project were also ana-lysed to support and enrich the interview data.

Interview transcripts and archived documentswere analysed for key themes emerging fromthe data, within a methodological frameworkinformed by actor-network theory and recentdevelopments of this theory in line with a mate-rial semiotic approach (discussed below). Keythemes were identified in the analysis as themost frequently mentioned issues and responsesto the interview questions. Many of these themescorresponded to key sustainability issues in thewheatbelt, including dryland salinity and thecost-price squeeze of agriculture. The analysispresented in this paper is restricted to the inter-sections between the Project and industrialagriculture, and does not consider alternativeconstructions of the wheatbelt landscapes includ-ing those of Indigenous peoples, alternativeagriculture, farm workers, or urban residents.

Extracts from transcripts are used to highlightkey points from analysis of several hundred

S. Bell:

Constructing Sustainable Rural Landscapes

199

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

pages of interview transcripts. The results of theanalysis are presented through the full descrip-tion of the case study, of which the extractsprovide supporting highlights, rather than defin-itive representation of the interview data. Theextracts were selected as particularly effectiveexpressions of main themes that emerged inthe analysis of the data, representing some ofthe most commonly-expressed responses to thequestions, and highlighting key sustainabilityissues from the wheatbelt. In the extracts, inter-view participants are designated by gender andthe decade of their age: M = man, W = woman,and the number indicates the decade of theirage (for example, M30 is a man in his thirties).Different participants of the same age categoryand gender are designated by letters: a, b, cor d.

Material semiotics

Material semiotics is an approach to the studyof science and technology which has beendeveloped in different ways by the Frenchphilosopher Michel Serres (Serres and Latour,1995) and the American feminist scholar DonnaHaraway (Haraway, 1991; 1997). Recently,material semiotics has been used to refer toextensions of actor-network theory by authorsincluding Bruno Latour (1993; 1996; 1999),John Law (1994; 1999; 2002; Law and Hassard,1999) and Annemarie Mol (1999; 2002). JohnLaw (1999, 7) described actor-network theory as‘a semiotic machine for waging war on essentialdifference’. Later (Law, 2002, 118), he definedsemiotics as

… the study of relations. More specifically, itis the argument that terms, objects, entities,are formed in difference between one another.The argument is that they don’t have essen-tial attributes but instead achieve their signi-ficance in terms of their relations, relationshipsof difference.

Actor-network theory extends the semioticinsight from language to materiality, thus hasbeen described as ‘material semiotics’ or ‘rela-tional materiality’ (Law, 1999, 4). It is a metho-dology that describes relationships among actorswithout drawing essential distinctions betweenhuman and non-human actors, social and naturalrelationships (Callon, 1986). It follows actorsthrough networks of material relationships thatthey constitute, and are constituted by, depictingrealities without recourse to fundamental, pre-existing categories of nature and culture (Latour,

1991; 1993; Law, 1992). Importantly, actors areboth human and non-human, including tech-nology, texts, and elements of the built andnatural environment.

Scholars in agri-food studies, rural sociologyand geography have engaged with actor-networktheory, attracted by its potential to overcomelimitations in existing theoretical approaches totheir subjects. In particular, scholars have beenattracted by the potential for actor-network the-ory to overcome the distinction between natureand culture which underpins other theoreticalapproaches, but which does not reflect the com-plex intermingling of human and non-humanelements of rural landscapes, industries andcommunities.

Actor-network theory was first used by ruralsociologists and geographers in the early 1990s.Clark and Lowe (1992, 11) examined its poten-tial for describing the ‘intimate relationshipbetween primary industries and the environment’,in particular the environmental consequencesof agriculture. They presented actor-networktheory as a means of overcoming the ‘naïvetechnology’ of social scientists who uncriticallysimplify the role of technology in agriculturalsystems, the symmetrical equivalent of the‘naïve sociology’ of agricultural and other sci-entists and technologists who lack knowledgeof the complexity of rural social life in theirattempts to develop and extend new agriculturaltechnologies. Actor-network theory’s focus onrelationships among human and non-humanactors allows the roles of technology, the envir-onment and people to be analysed as parts ofnetworks of relationships which construct ruralplaces and industries. This simultaneous atten-tion to human and non-human elements helpsovercome both naïve sociology and naïve tech-nology which arise from analyses which arerooted in either side of the nature-culture, orscience-society divides.

The analysis of the wheatbelt through net-works of relationships among human and non-human actors presented in this paper draws onearlier geographical applications of actor-network theory to rural and agricultural issues.Jonathon Murdoch applied actor-network theoryto questions of rural geography and agri-foodstudies early in the 1990s, and contributed sig-nificantly to its development as a methodologyfor sustainability and geographical studies(Murdoch and Clark, 1994; Murdoch andMarsden, 1995; Murdoch 1997). Busch and col-leagues drew on actor-network theory in studies

200

Geographical Research

•

June 2005

•

43(2):194–208

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

of food commodities such as canola (Juska andBusch, 1994; Busch and Tanaka, 1996; Buschand Juska, 1997) and soy beans (De Sousa andBusch, 1998). Environmental history, ecologicalMarxism, actor-orientated rural sociology, andsystems theories are among the frameworksreviewed by Margaret FitzSimmons and DavidGoodman in proposing actor-network theory asa means of avoiding the ontological limitationsimposed by the dualist construction of naturewhich underpinned earlier theoretical approaches(FitzSimmons and Goodman, 1998; Goodman1999; 2001). Lockie and Kitto (2000) reviewedthese early applications of actor-network theoryin agri-food studies and concluded that Good-man’s attention to the ontological implicationsof the methodology holds the most promisein providing original insight into agri-foodquestions. Sarah Whatmore (2002) has alsoused actor-network theory in geographicalstudies, including studies of wildlife, food, plantgenetics and land tenure, and her theoreticaldevelopment of ‘hybrid’ geographies is aparticularly valuable contribution in this area.Many of the issues addressed by these authors,including issues of rural sustainability, globalagri-business and agri-food systems, and therelationships among agricultural technologies,farmers and the environment, are highly rele-vant in the wheatbelt context, and provide astrong foundation for the use of actor-networktheory in analysing the possibilities for sustaina-ble wheatbelt landscapes.

Sustainability confounds the nature-culturedualism. Neither science nor culture, politics orsociety, is sufficient alone to comprehend andrespond to the challenges of sustainability.Material semiotics’ and actor-network theory’sattention to overcoming these dualisms providesa useful methodology for analysing sustain-ability issues and responses to them. This theoryprovides a framework for the analysis of thewheatbelt and the Oil Mallee Project, and isevident in the attention to material relation-ships between human and non-human actors.In particular, the theory highlights the role oftechnologies in shaping the wheatbelt and inconnecting landscapes to global networks ofagri-industry, revealing opportunities andbarriers for the Oil Mallee Project and sus-tainability. Material semiotics enables detailedinterrogation of York Main’s (1971) vision ofthe wheatbelt as the confluence of ancient land-scape and contemporary agricultural artefactsand practices.

Constructing the wheatbelt

Clearing

During much of the twentieth century theancient flow of the landscapes that became theWestern Australian wheatbelt was disruptedby clearing vegetation to create paddocks forcropping and grazing. Clearing dramaticallychanged the landscape. The paddocks formedfrom cleared land most dramatically signifynon-indigenous patterns of production. As wellas the immediate physical changes, land clear-ing also set the pattern for technologically-mediated, productive relationships in the wheat-belt, particularly the use of heavy machineryand the reliance on chemical inputs and exoticcrops to allow agriculture on otherwise-infertile,sandy soils. In line with insights from actor-network theory, industrial technologies have beencentral actors in the networks of relationshipsthat have shaped wheatbelt agriculture since itsvery beginnings.

The role of machinery in reshaping wheatbeltlandscapes is described by a farmer who wasinvolved with clearing land in the second post-war development boom.

M50a: No clearing’s been done for a longtime but in the late fifties early sixties wellheaps of country was cleared. Patches of fairsized york gum trees in some cases wecleared with a dozer, some reasonablepatches of trees we also cleared with a chainpulled between two crawler tractors. Some-times the trees were too big for the chain topull them down so we had to have a dozerthere with a blade on it or a tree pusher on itto push them over but, yes it certainlychanged the landscape a bit, a fair bit (farmerinterview transcript, 2001).

This description of typical clearing practice afterWorld War Two highlights the important role ofmodern, industrial technologies, and their rela-tionships to people, land and vegetation in theconstruction of wheatbelt landscapes. Whileclearing no longer occurs on the same scale asit did during the 1950s and 1960s, networks ofrelationships between humans, technologies,land and vegetation continue to shape wheatbeltlandscapes.

Land clearing was facilitated by technologicaldevelopments, particularly developments infertilisers and crops which enabled country thatwas previously unsuitable for cropping tobecome productive. As Burvill (1979, 116)

S. Bell:

Constructing Sustainable Rural Landscapes

201

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

described in his sesquicentennial history ofWestern Australian agriculture,

Super, sub clover, lupins, trace elements andreturns from wool and wheat were keys to thegreat wave of new land development 1947–68, which converted millions of hectares in arural sense from poverty to plenty.

This pattern of science-led innovation is one thathas continued to shape farming and landscapesin the wheatbelt.

Land clearing is the root cause of the currentproblem of dryland salinity, and reversing landclearing by developing a commercial tree cropis the main motivation for developing an oilmallee industry. Dryland salinity is a significantfeature of contemporary wheatbelt landscapes,presenting a breakdown in the relationshipsbetween modern agriculture and the ancientrealities of land. All of the farmers in my studyare now working to reverse land clearing byplanting trees, including oil mallees. Theyplanted oil mallees because of the possibilityof a commercial return sometime in the future,and the possibility that dryland salinity can bemanaged by integrating indigenous trees withexisting agricultural enterprises.

The chemical generation

Most land that is suitable for agricultural pro-duction in the wheatbelt region has now beendeveloped, and the rate of land clearing for agri-culture has declined since the 1970s. However,science-led innovation has continued its centralrole in Western Australian agricultural develop-ment. New cropping techniques, particularlyminimum tillage, and the use of geographicinformation systems, global positioning systemsand automation, are increasing the accuracy andproductivity of farming in the wheatbelt. Thecontinued introduction of new technologies tofarms strengthens relationships between farmersand international networks of industrialagriculture, confirming the role of agriculturaltechnologies in shaping wheatbelt landscapes.

Throughout the 1990s, annual cropping inWestern Australia was transformed by the wide-spread adoption of minimum tillage farmingtechniques. These methods reduce ploughingand harrowing of the soil, conserving moistureand reducing erosion, but depend on muchhigher usage of synthetic chemicals than oldertechniques. Promoted as ‘conservation farming’,minimum tillage has generally resulted inimproved productivity as well as soil condition

(Conacher and Conacher, 1995). These technol-ogies strengthen material relationships betweenfarmers and international networks of chemicalproduction and sale.

The heavy use of chemicals and the conse-quently increasing role of chemical companyagronomists in family farming decisions areamong the drawbacks of minimum tillage. Col-lective ambivalence towards minimum tillageremains, despite widespread adoption and rec-ognition of its role in reducing land degradation(Conacher and Conacher, 1995; Lockie, 2001b).This ambivalence is evident in the followingdiscussion between a group of farmers. In thisdiscussion, the men promote the benefits ofconserving soil moisture using minimum tillagetechniques despite negative perceptions of highchemical use, while one of the women expressesthe possibilities for alternative farming tech-niques which conserve soils and biodiversitywithout high chemical use.

M20a: See farming to me is fighting weeds,that’s what we do, we’re weed fighters … wedefinitely are the chemical generation nodoubt about that, coz we are totally reliant onthem … but chemicals allow us to minimumtill. Chemicals allow us … .

W20a: I understand you need chemicals.

M20b: They allow you to conserve moisturein the long-term, which is a rare thing.

M20a: See you get a lot of people saying‘you’re using chemicals it’s really bad, I hatechemicals’ … alright we can do it the oldmethod and you’ll see our farm blowing overthe ocean. We’re actually better for theenvironment by using them.

M20c: In the long-term I think we are, yeah.

W20b: But if you spoke to someone who wasright into biodiversity and they would totallydisagree with the lot. They reckon therewould be other methods, like in the long-term, that could solve those problems (farmerinterview transcript, 2001).

The increased usage of chemical herbicides andthe complexity of managing herbicide resistancehave increased material relationships betweenchemical companies and farmers. However, thedependence on chemical companies, the cost ofthe herbicides and the influence of chemicalcompany agronomists on farm decisions isresisted by some farmers, despite the benefits of

202

Geographical Research

•

June 2005

•

43(2):194–208

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

minimum tillage techniques in improved pro-ductivity. Describing her ideal future, onefarmer wanted more control over the marketingof produce, and for chemical companies to haveless control over her family farming decisions.Alternatives such as organic farming systemsare considered unlikely to succeed in the localconditions of her farm.

W20c: And chemical companies not runningyour lives as well. Well not running yourlives, running your — they seem to run theshow as far as bringing out new things thatyou have to use because — it’s a viciouscircle.

Sarah: So what would be an alternative tothat?

W20c: We buy them [the chemical companies].

M20d: I don’t think that organic would reallybe the way to go out here.

W20c: I don’t either (farmer interview tran-script, 2001).

While there are alternative techniques for con-servation farming which do not use chemicals,these systems find it difficult to engage farmerswho are strongly connected to existing agri-foodnetworks and the vicious circle of chemicaldependence and market powerlessness. Chemicalcompanies have become powerful providers tofarmers who are interested in staying at the headof the innovation treadmill, conserving topsoiland maintaining profitability. The material rela-tionships between farmers and the industrialagri-food network are numerous and powerful,and are dominant in shaping rural landscapes.

Despite the seeming inevitability of theserelationships, farmer resistance to chemicalcompany power and community concern aboutincreased chemical use in agriculture providespaces in which new industries such as theOil Mallee Project can emerge. In exploitingpoints of resistance, alternatives to dominantnetworks must establish new patterns of produc-tion, which respond to both the underlying real-ities of soil, weather and other landscapeecological conditions, and the strength ofexisting relationships binding farmers to thetechnological treadmill.

On the treadmill

Wheatbelt farmers are connected to industrialagricultural networks through the commoditymarkets they sell their products into, as well as

through technologies of production like syn-thetic herbicides, fertilisers and machinery. Thetreadmill of technological innovation is stronglyconnected to international commodity marketconditions, confirming the networked reality ofmaterial relationships that are shaping thewheatbelt (Goodman and Redclift, 1991).

Participants in this research described thetechnological treadmill, and the associated cost-price squeeze, as the main challenge facingfarmers and agriculture in Western Australia.Declines in the real prices for commodities onthe global market drives a cycle of over-produc-tion as farmers try to increase production andefficiency to maintain profit margins, therebyexacerbating the food overproduction whichkeeps prices low (Goodman and Redclift, 1991).

Farmers who participated in the research allspoke extensively about the cost-price squeezeand its impact on their farms, families and com-munities. The cost-price squeeze is the outcomeof international networks of markets and inputs,highlighting the global reach of relationshipsshaping the wheatbelt. Agricultural policies inEurope and the United States, which subsidiseagriculture, are seen by farmers as contributingto the low prices driving the cost-price squeeze,and continuing uptake of more productive tech-nologies. None of the farmers expressed partic-ular hope in the removal of subsidies overseas,or called for similar subsidies to be applied inAustralia. In discussions about subsidies, onefarmer who had recently returned from theUnited States recounted discussions with USfarmers, with their ‘rich chocolattie brown soil’,who didn’t fare any better, even with subsidies.

The farmers interviewed spoke proudly oftheir ability to efficiently produce high qualityfood from poor soils and to maintain their prof-itability in competition with subsidised farmersin other countries. This productivity has beenachieved through intense application of newtechnologies, which dramatically shape rurallandscapes. However, many of the farmersexpressed concern that increases in productivityexperienced in the last decades of the twentiethcentury are approaching upper limits. Theawareness of the accumulation of profit bychemical and machinery companies at theexpense of farmers, and the lack of control theyhave over these processes, also contributes toscepticism about the potential for further inno-vation to continue to improve or maintain theirown profitability over the longer term. As onecouple explained,

S. Bell:

Constructing Sustainable Rural Landscapes

203

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

W30: West Australian farmers are probablythe most efficient farmers in the world. Tocombat the declining terms of trade you haveto become more efficient and I’m not surehow much more efficient that they can get. Ithink that’s because they’re so far aheadalready.

M30: We are pushing the production limitshere. Huge global companies which makefertilisers and chemicals and can charge whatthey like and essentially we are price takers(farmer interview transcript, 2001).

Reservations such as these indicate that thestrength of current relationships between indus-trial networks and wheatbelt landscapes is notassured indefinitely. While current agriculturalpractice is strongly tied to international net-works of technology and commodity sales,many of the participants in my research indi-cated that limits are being reached. The localrealities of soil degradation, as well as declininglocal economic activity and shrinking farmprofit margins in the face of capital accumula-tion by international agri-business and technol-ogy companies, provide points of weakness indominant networks. These limits and points ofbreakdown provide opportunities for reconfigur-ing relationships among people, technology andland in ways that enable sustainability.

The cost-price squeeze provides an incentivefor farmers to diversify their incomes and for thedevelopment of new industries which are notpart of existing agri-food networks. One protag-onist of the Oil Mallee Project linked the impli-cations of improved market and productioninformation to food production and the need todevelop more unique products from agriculturein Western Australia.

M50b: I guess the other problem with beinglocked into the food cycle, the world foodcycle, is that competition is increasingthrough technology at an ever-increasing rateas well, and that, in my opinion, is one of thereasons why we’ve got to look at alternativesthat other people can’t do as well as what wecan. Whether it be through subsidies or not…

I think that one of the challenges is to startproducing things that are unique, moreuniquely suitable to [local] conditions.CALM and the Farm Forest Program and theSearch Program and things like that are abso-lutely essential and we could probably put a

lot more emphasis on those alternatives (OilMallee Association interview transcript, 2001).

On the margins

One of the successes of industrial agriculturehas been to enable the productive use of land ofmarginal fertility for cropping and intensivegrazing. Some of the areas now farmed byparticipants in my research were cleared andbrought into production only recently whenindustrial inputs, particularly trace element fer-tilisers, and the legume lupin, became availableto enable productive use of sandy soils. Theprofitability of agriculture on these soils is morevulnerable to changes in input costs and marketfluctuations than in other, more productiveareas. Despite high dependence on industrialinputs, vulnerability to changes in prices andenvironmental conditions mean that these landsare where the connections to industrial networksare weakest, providing spaces for more sustain-able alternatives to emerge.

The position of marginal lands in the indus-trial agri-food network has always been tenuous.Their cultivation is more sensitive than morefertile areas to changes in environmental condi-tions and prices for agricultural inputs and prod-ucts. Farms on the edge of reliable rainfall zonesare more susceptible to adverse seasons. Withinfarms, low productivity areas of soil are amongthe places where farmers are most likely torevegetate. One of the strengths of the OilMallee Project, according to one participant, isthe fact that mallees ‘grow on pretty crappyground’. The tenuous position of some soiltypes in industrial agriculture networks providesan opportunity for the Oil Mallee Project toengage farmers who are looking for alternativesto pouring inputs on to this land with minimalreturn. The Project has the potential to providean alternative to the technological treadmillresponse to the cost-price squeeze. In marginallands, the farmers interviewed were looking toaddress the cost-price squeeze by reducing inputcosts, while in more productive areas theycontinued to address the squeeze by increasingproduction. New technology for mapping yieldswithin paddocks confirms the techno-industrialvisions of wheatbelt lands, while helping farmersto identify poorly-performing areas of paddocksso they can look for specific alternatives forthose patches.

M20c: … our main drama is the sandy areasof our paddock perhaps the hills and stuff

204

Geographical Research

•

June 2005

•

43(2):194–208

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

which are really low productive. You can seebig patches of our paddock that will nevergrow a decent crop so what do you do withthose areas? So I’m looking at oil mallees.We may plant these particular areas in ourpaddocks down to oil mallees. So you get areturn on them long-term that is greater thansay half a tonne of …

Sarah: And you use soil mapping? What’s the…?

M20a: Yield mapping.

M20c: Yeah we’ve been doing that for fouryears. It’s consistent, same patches, samepaddocks every year, regardless of what thecrop is. Always goes really badly. Just tryingto figure out what to do with these. WhetherI plant a pasture in ‘em, don’t think we’llever have a perennial pasture unless it’s a tree… but I think oil mallees could be the solu-tion if they look like they are going to turn adollar or two (farmer interview transcript,2001).

The full-scale, commercial development of anoil mallee industry will require mallees to begrown on the most productive land, in order tomaximise mallee productivity and provide thevolume of biomass necessary to supply process-ing plants. Within the Oil Mallee Project therehas been some effort made to try to convincefarmers not to plant mallees in their worst per-forming country but to maximise the perform-ance of the trees by planting in better soil andmicroclimates. In the longer term, if commercialreturns are realised, this may be a rationaldecision for farmers, but in the shorter termthe enrolment of farmers in the Project is morelikely to be in terms of conservation concerns onmore marginal soil. Land that performs poorlywithin existing networks provides space for oilmallees to enter the landscape and begin toimprove sustainability.

Mallee alleys

While working at the points of weakness inexisting networks, the Project has strategicallypromoted itself as integrating with existingenterprises, rather than replacing them. Ratherthan directly resisting industrial agriculture andaiming to replace it, mallees are envisionedgrowing in rows, with conventional croppingand grazing continuing in between (Lefroy andScott, 1994). Thus landscape sustainability inthe wheatbelt is conceived as a hybrid network,

linking industrial agricultural technologies andpractices to specific local industries producingwood, chemicals and energy from indigenousspecies. The locally indigenous trees providenew knots tying industrial agriculture back tothe ancient realities of the landscape, along thelines of York Main’s (1971) vision.

Industrial agriculture in the wheatbeltinvolves large, open, square paddocks that mosteasily enable mono-cropping using very large-scale heavy machinery. Increased mechanisationand automation of agricultural equipment haveincreased the speed and efficiency of operationsin the paddock, at the expense of manoeuvrabil-ity. Uniform paddocks are the material conse-quence of the relationships between farmer, landand machine, and alley-farmed paddocks, withtrees spaced according to the requirements oflarge machinery, most dramatically signify newpatterns of relationship between industrialagriculture and the local landscape.

The Oil Mallee Project must exist in andtransform contemporary wheatbelt spaces if it isto succeed in reconnecting industrial networksto the underlying land. In a presentation toa select committee of the New South WalesGovernment, Project champion, John Bartle,described the strategy of linking oil mallees intothe existing industrial systems which shapewheatbelt farms.

We knew we had to have a production systemthat could be at home in amongst the veryextensive production systems that farmerspresently use, where some 5000 or 6000farmers manage some 18 million hectares ofwheat belt lands in Western Australia. Theonly time they cover every hectare is whenbig machines go across it. They do not get allthat close to the land in those sorts of sys-tems in a direct sense. We were determinedto make sure that these systems featured inwell (Bartle, 2002).

The new pattern of knots tying together indige-nous trees and industrial agriculture is mostevident in the arrangement of the alleys. Rowsof trees are laid out according to machinerywidths and manoeuvrability.

Sarah: So what would you want from the oilmallees to go into say a bigger scale like analley farming system? Would you ever dothat?

M50a: Not … I don’t know. Unless the pricefalls right out of wheat production and lupin

S. Bell:

Constructing Sustainable Rural Landscapes

205

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

production and that, I can’t see how you’djust change over and just do that.

M20d: Now the alley farming you’re doingboth. So you’d have two rows of mallees andleave 30 m in between or whatever, the widthof your boom spray. So you have two passeswith your seeder bar, through there once withyour airseeder and then another couple ofrows of trees. I heard there’s a guy outMullewa somewhere’s done a heap of coun-try like that this year, I think he did 1000acres [405 hectares] or something. He wasgoing to plant trees in rows and leave thatgap between there. Which, I dunno, suppos-edly you’d be stopping your wind erosion orwhatever and your crop would be out of theelements (farmer interview transcript, 2001).

Making money

The overwhelming response to my question‘What would make farmers plant more oilmallees?’ was improvement in the commercialviability of planting, through commercial devel-opment of the industry. Commercial success forthe Oil Mallee Project may signify another typeof corporate interest, additional to the existinginfluence of agribusiness corporations, in wheat-belt landscapes. Large corporations investing inmallee plantings will signify the intersection ofagronomic and tree planting decisions on farms.This challenges existing agronomic networks,including the relationships between bankers,financial advisers and farmers. The relationshipsbetween farmers and private financial and agro-nomic advisers have been strengthened in recentdecades, corresponding to a withdrawal of gov-ernment advisory and extension services. Exist-ing networks of finance and investment inagribusiness are well established, powerful anddifficult for oil mallees to join, as noted by aprotagonist of the Project.

M50b: I think that’s why it’s pretty importantfor people like bankers and farm manage-ment consultants to be up on what the poten-tial is. Even if it’s not totally stand alone atthe moment, they need to be in on the wholeprocess so that when basically the first loadsof material are harvested and it can show areturn, someone like a Japanese power com-pany’s come along and say ‘OK we want 10000 hectares of land to plant mallees on, andget a lease type rate return with a harvestedprofit every other year’, or someone like that.We need someone else, other than the Oil

Mallee Company, out there actively, beforethe Association, there needs to be the finan-cial benefit of telling the growers ‘this isreally worth pursuing,’ when and if thathappens. They need to be up to speed, theyneed to be involved in it … . And there’s lotsof very bright people there and they could bemaking positive contributions rather thanknocking it as though, it’s nice but they won’thave a bar of it. In fact, I’d say 100 % ofthem won’t have a bar of it (Oil Mallee Asso-ciation interview transcript, 2001).

Integrated farming

Breakdowns in the connections between industrialagricultural networks, the land, and socio-economic aspirations of farmers provide oppor-tunities for new patterns of farming, indicatedby the Oil Mallee Project, to emerge.

M20a: A pure opportunity [for the Oil MalleeProject] is integrated farming. When we saywe’re weed fighters, and we are workingbackwards, the weeds are stepping up. Andalso you’re getting salinity coming up as welland especially all your summer rainfall that’sadding to your salinity straight away becauseyou’re not using that. So you have a peren-nial there that once it’s big enough the weedsaren’t going to worry about, you don’t haveto pay CSBP [local fertiliser manufacturingcompany] huge amounts of money. So yeah,how to use the country and making a reallygood profit out of it but to get to that stage, Ijust … make us go from pure farming in onedirection and do that is huge leap hey, I don’tthink we’ll see it in my generation (farmerinterview transcript, 2001).

‘Integrated farming’, with increased use of per-ennial species like oil mallees, is a hybridresponse to the technology treadmill, high input,cost-price squeeze of modern industrial agri-food networks. The transition from currentindustrial systems to a more integrated approachis a huge change and seems unlikely to occur inthe current generation of farmers. The OilMallee Project is therefore a prophet of futurefarming, beyond the agri-food treadmill, degra-ding land and declining rural communities. TheProject is important in demonstrating the possi-bility of alternative relationships among farmers,land, plants, agriculture and industry. It is alsosignificant for its strategy of reconfiguring exist-ing relationships rather than directly resistingdominant networks of production.

206

Geographical Research

•

June 2005

•

43(2):194–208

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

Towards rural sustainability

Contemporary wheatbelt landscapes are shapedlargely by industrial networks and technologies.However, an analysis informed by materialsemiotics shows that these relationships, whilepowerful, are not monolithic or inevitable.Breakdowns in the connections between indus-trial networks, the ancient land and the aspira-tions of farmers provide opportunities for newpatterns of farming, indicated by the Oil MalleeProject. The Project provides the possibility toexploit a number of these points of weakness inexisting networks and to develop integratedfarming systems which improve the sustainabil-ity of the region and landscape. In responding tothe ecological crisis of dryland salinity, theProject aims to create a new industry usinglocally indigenous species, which will be inte-grated with existing, conventional agriculturalenterprises. The mallees provide new knotstying global agriculture to the land.

Analysing landscapes within a framework ofmaterial semiotics reveals possibilities for recon-figuring relationships and landscapes towardssustainability, and the hurdles that remain. Therelationships that shape contemporary wheatbeltspaces are as close as farmer and tractor and asfar apart as wheatbelt soil and global consumers.Following these relationships through networksof human and non-human actors reveals pointsof weakness that provide strategic opportunitiesto pursue sustainability, despite the current dom-inance of the global forces of techno-industrialagribusiness. Material semiotics helps to high-light the potential for landscape sustainability asa hybrid of industrial agricultural and locally-specific production systems. In highlighting thepossibilities for the Oil Mallee Project to recon-figure relationships that construct contemporarywheatbelt landscapes, material semiotics opensup prospects for sustainable rural landscapesthat move beyond polarised debates betweenindustrial and alternative agricultural systems.

In order to achieve agricultural sustainabilityit is imperative that patterns of human settle-ment, cultivation and technology are tied back tothe ecology of the underlying earth. The dis-juncture between patterns of agricultural devel-opment in Australia and the underlying realitiesof the land have become apparent in the expan-sion of saline land areas, soil erosion, invasionof weeds and feral animals and other ecologicalcrises. Breaks in the networks of industrialagriculture are emerging as farmers start to lookbeyond the limitations of the technological

treadmill and high-input techniques. Thesebreaks provide opportunities for new industriesand patterns of development to build novel rela-tionships among people, technology and land,reconfiguring rural landscapes for sustainability.

Although ecological and socio-economic con-cerns emerge as weak spots in the networks ofindustrial agriculture, the relationships thatcomprise these networks remain very powerful.Agribusiness and financial services remainfirmly connected to existing industries, andchemical and machinery suppliers are powerfulagents in shaping farms. Strategies for con-structing sustainable rural landscapes must rec-ognise the power as well as weaknesses in thenetworks that currently shape patterns of arte-facts and practice. Developing new industriesfrom indigenous species, which can provide aneconomic return that is similar to conventionalagricultural products, will allow for the transi-tion to truly integrated farming models, and willfacilitate the return of local species to produc-tive as well as degraded parts of the landscape.Transforming landscapes for sustainability isunlikely to occur quickly. It requires buildingnew relationships among people, technologyand land that can be stabilised amid the oftencontradictory demands of modern agriculturalnetworks and the underlying earth.

Correspondence

: Dr Sarah Bell, Department of Civil andEnvironmental Engineering, University College London,Gower St., London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom. E-mail:[email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe work presented in this paper was undertaken duringmy PhD candidature at Murdoch University, supervised byDr Laura Stocker, Associate Professor Allan Barton and DrSusan Moore, and supported by a Murdoch UniversityResearch Scholarship.

NOTES1. The salinity benefits of tree planting in the wheatbelt

were contested in scientific and other publications dur-ing 1999 and 2000 (George

et al.

,

1999; Hatton and Salama,1999; George

et al.

,

2001). Hydrological research chal-lenged the benefits of planting trees on the scale ini-tially promoted by the Oil Mallee Project. John Bartle,from the Department of Conservation and Land Man-agement, refuted some of the science behind the ‘pes-simistic’ claims of the hydrologists, and rejected anyimplication that efforts to slow the spread of salinity,including tree planting, were futile (Bartle, 1999a; 1999b).

2. The Search Program within the Department of Con-servation and Land Management (CALM) aims tosystematically assess indigenous flora for potentialcommercial development for crops in low rainfall agri-cultural areas, following the model of oil mallees.

S. Bell:

Constructing Sustainable Rural Landscapes

207

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

REFERENCESAdams, W., 2001:

Green Development: Environment andSustainability in the Third World

. Routledge, London andNew York, 2nd ed.

Bartle, J., 1999a: Why Oil Mallee? Presented at The OilMallee Profitable Landcare Seminar, Pastoral House,Belmont, Western Australia.

Bartle, J., 1999b: The New Hydrology: New Challenges forLandcare and Tree Crops. Presented at Western AustralianBankWest Landcare Conference, Esperance, WesternAustralia.

Bartle, J., 2002: Presentation to NSW Parliamentary Com-mittee on Salinity. Presented at Salinity Solutions Seminar,Sydney.

Bartle, J., Campbell, C. and White, G., 1996: Can TreesReverse Land Degradation? Paper presented at AustralianForest Growers Conference, Mt Gambier, South Australia.

Barton, A., 2000: The Oil Mallee Project: a multifacetedindustrial ecology case study.

Journal of IndustrialEcology

3, 161–176.Bell, S., Barton, A., and Stocker, L., 2001: Agriculture for

health and profit in Western Australia: the Western OilMallee Project.

Ecosystem Health

7, 116–121.Beresford, Q., Bekle, H., Phillips, H. and Mulcock, J., 2001:

The Salinity Crisis. Landscapes, Communities and Politics

.University of Western Australia Press, Perth.

Berry, W., 1986:

The Unsettling of America: Culture andAgriculture

, Sierra Club Books, San Francisco.Beus, C.E. and Dunlap, R.E., 1990: Conventional versus

alternative agriculture: the paradigmatic roots of thedebate.

Rural Sociology

55, 590–616.Black, A., Forge, K. and Frost, F., 2000: Extension and

Advisory Strategies for Agriforestry. RIRDC PublicationNo 00/184, Rural Industries Research and DevelopmentCorporation, Canberra.

Bryant, L., 2001: A job of one’s own. In Lockie, S. and Bourke,L. (eds)

Rurality Bites

. Pluto Press, Sydney, 214–226.Burvill, G.H., 1979:

Agriculture in Western Australia. 150Years of Development and Achievement 1829–1979

.University of Western Australia Press, Perth.

Busch, L. and Juska, A., 1997: Beyond political economy:actor networks and the globalization of agriculture.

Review of International Political Economy

4, 688–708.

Busch, L. and Tanaka, K., 1996: Rites of passage: construct-ing quality in a commodity subsector.

Science, Technologyand Human Values

21, 3–27.Callon, M., 1986: Some elements of a sociology of transla-

tion: domestication of the scallops and the fishermen ofSt Brieuc Bay. In Law, J. (eds)

Power, Action and Belief.A New Sociology of Knowledge?

Routledge and KeganPaul, London, 196–233.

Clark, J. and Lowe, P., 1992: Cleaning up agriculture:environment, technology and social science.

SociologiaRuralis

32, 11–29.Collins, Y., 2001: The more things change the more they

stay the same: health care in regional Victoria. In Lockie,S. and Bourke, L. (eds)

Rurality Bites

. Pluto Press,Sydney, 103–117.

Conacher, A. and Conacher, J., 1995:

Rural Land Degrada-tion in Australia

. Oxford University Press, Melbourne.Davidson, A., 2001: Farming women and the masculinisa-

tion of farming practices. In Lockie, S. and Bourke, L.(eds)

Rurality Bites

. Pluto Press, Sydney, 204–213.De Sousa, I.S.F. and Busch, L., 1998: Networks and agricul-

tural development: the case of soybean production andconsumption in Brazil.

Rural Sociology

63, 349–371.

Ferdowsian, R., George, R., Lewis, F., McFarlane, D., Short, R.and Speed, R., 1996: The Extent of Dryland Salinity inWestern Australia. 4th National Conference and Work-shop on the Productive Use and Rehabilitation of SalineLands, Promaco Conventions, Albany, Western Australia.

FitzSimmons, M. and Goodman, D., 1998: Incorporating nature.Environmental narratives and the reproduction of food. InBraun, B. and Castree, N. (eds)

Remaking Reality: Natureat the Millenium

. Routledge, London, 194–220.Geno, B., 2001: Gender-based differences in approaches to

managing farms sustainably. In Lockie, S. and Pritchard,W. (eds)

Consuming Foods Sustaining Environments

.Australian Academic Press, Brisbane, 189–204.

George, R.J., Clarke, C.J. and Hatton, T., 2001: Computer-modelled groundwater response to recharge managementfor dryland salinity control in Western Australia.

Advancesin Environmental Monitoring and Modelling

2, 3–35.

http://www.kcl.ac.uk/advances

.George, R.J., Nulsen, R.A., Ferdowsian, R. and Raper, G.P.,

1999: Interactions between trees and groundwaters inrecharge and discharge areas — a survey of Western Aus-tralian sites.

Agricultural Water Management

39, 91–113.Gerritsen, R., 2000: The management of government and

its consequences for service delivery in regional Australia.In Pritchard, W. and McManus, P. (eds)

Land of Discon-tent. The Dynamics of Change in Rural and RegionalAustralia

. University of New South Wales Press, Sydney,123–139.

Goodman, D., 1999: Agri-food studies in the ‘age of ecology’:nature, corporeality, bio-politics.

Sociologia Ruralis

39,17–38.

Goodman, D., 2001: Ontology matters: the relational mate-riality of nature and agri-food studies.

Sociologia Ruralis

41, 182–200.Goodman, D. and Redclift, M., 1991:

Refashioning Nature:Food, Ecology and Culture

. Routledge, London.Goodman, D. and Watts, M., 1997:

Globalising Food: AgrarianQuestions and Global Restructuring.

Routledge, London. Gray, I. and Lawrence, G., 2001:

A Future for RegionalAustralia. Escaping Global Misfortune.

CambridgeUniversity Press, Cambridge.

Haraway, D., 1991:

Simians, Cyborgs and Women: theReinvention of Nature

. Free Association Books, London.Haraway, D., 1997:

Modest_Witness@Second_Millenium.Female_Man_Meets_Oncomouse: Feminism and Techno-science

. Routledge, New York.Hatton, T. and Salama, R., 1999: Is it feasible to restore the

salinity-affected rivers of the Western Australian wheat-belt? In Rutherfurd, I. and Bartley, R. (eds),

Second Aus-tralian Stream Management Conference — The Challengeof Rehabilitating Australia’s Streams

1, 313–317.Jacobs, M., 1999: Sustainable development as a contested

concept. in Dobson, A. (ed.)

Fairness and Futurity

.Oxford University Press, Oxford, 21–45.

Juska, A. and Busch, L., 1994: The production of knowledgeand the production of commodities: the case of rapeseedtechnoscience.

Rural Sociology

59, 581–597.Latour, B., 1991: Technology is society made durable. In

Law, J. (eds)

A Sociology of Monsters: Essays on Power,Technology and Domination

. Routledge, London, 103–131.

Latour, B., 1993:

We Have Never Been Modern

. PearsonEducation Ltd, Harlow, Essex.

Latour, B., 1996:

Aramis, or the Love of Technology

. HarvardUniversity Press, Cambridge, Massacusetts.

Latour, B., 1999:

Pandora’s Hope

. Harvard UniversityPress, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

208 Geographical Research • June 2005 • 43(2):194–208

© Institute of Australian Geographers 2005

Law, J., 1992: Notes on the theory of the actor-network:ordering, strategy, and heterogeneity. Systems Practice 5,379–393.

Law, J., 1994: Organizing Modernity. Blackwell Publishers,Oxford.

Law, J., 1999: After ANT: complexity, naming and topology.In Law, J. and Hassard, J. (eds) Actor Network Theoryand After. Blackwell, Oxford and Malden, 1–14.

Law, J., 2002: Objects and spaces. Theory, Culture and Soci-ety 19, 91–105.

Law, J. and Hassard, J. (eds), 1999: Actor Network Theoryand After. Blackwell Publishers, Oxford.

Lefroy, T. and Scott, P., 1994: Alley farming: new vision forWestern Australian farmland. Western Australian Journalof Agriculture 35, 119–132.

Lockie, S., 2001a: Community environmental management?Landcare in Australia. In Lockie, S. and Bourke, L. (eds)Rurality Bites. Pluto Press, Annandale, 243–256.

Lockie, S., 2001b: Agriculture and environment. In Lockie,S. and Bourke, L. (eds) Rurality Bites. Pluto Press,Annandale, 229–242.

Lockie, S. and Kitto, S., 2000: Beyond the farm gate:production-consumption networks and agri-food research.Sociologia Ruralis 40, 3–19.

Lockie, S. and Pritchard, W., 2001: Consuming Foods Sus-taining Environments. Australian Academic Press, Brisbane.

Lockie, S. and Vanclay, F., 1997: Critical Landcare. Centrefor Rural Social Research, Wagga Wagga, Australia.

Mol, A., 1999: Ontological politics: a word and some ques-tions. In Law, J. and Hassard, J. (eds) Actor Network Theoryand After. Blackwell, Oxford and Malden, 74–89.

Mol, A., 2002: The Body Multiple. Duke University Press,Durham.

Murdoch, J., 1997: Inhuman/nonhuman/human: actor-network theory and the prospects for a nondualistic and

symmetrical perspective on nature and society. Environ-ment and Planning D: Society and Space 15, 731–756.

Murdoch, J. and Clark, J., 1994: Sustainable knowledge.Geoforum 25, 115–132.

Murdoch, J. and Marsden, T., 1995: The spacialization ofpolitics: local and national actor-spaces in environmentalconflict. Transactions of the Institute of British Geogra-phers 20, 368–380.

Pannell, D., and Schilizzi, S., 1999: Sustainable agriculture:a question of ecology, ethics, economic efficiency or expedi-ence? Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 13, 57–66.

Pritchard, W. and McManus, P. (eds), 2000: Land of Discon-tent. The Dynamics of Change in Rural and RegionalAustralia. University of New South Wales Press, Sydney.

Serres, M. and Latour, B., 1995: Conversations on Science,Culture and Time. University of Michigan Press, AnnArbor.

Shea, S., 1998: Farming carbon. Landscope. Department ofConservation and Land Management, Perth, WesternAustralia.

Stucley, C., 1999: Integrated Processing of Oil Mallee Treesfor Activated Carbon, Eucalyptus Oil and RenewableEnergy. Presentation to The Oil Mallee Profitable Land-care Seminar, Perth, Western Australia.

Tonts, M. and Selwood, J., 2003: Niche markets, regionaldiversification and the reinvention of Western Australia’sSandalwood industry. Tijdschrift voor Economische enSociale Geografie 94, 564–575.

Wallace, K.J., 2001: State Salinity Action Plan 1996. Reviewof the Department of Conservation and Land Manage-ment’s Programs, Western Australian Department ofConservation and Land Management, Perth.

Whatmore, S., 2002: Hybrid Geographies. Sage, London.York Main, B., 1971: Twice Trodden Ground. Jacaranda

Press, Brisbane.