Conservation of threatened amphibians in Sweden Claes Andrén Nordens Ark

Conservation priorities for the most threatened amphibians in Venezuela, a preliminary approach

-

Upload

denis-torres -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Conservation priorities for the most threatened amphibians in Venezuela, a preliminary approach

Conservation priorities for the most threatened amphibians in Venezuela, a preliminary approach

21

CONSERVATION PRIORITIES FOR THE MOST THREATENED AMPHIBIANS

IN VENEZUELA, A PRELIMINARY APPROACH

BARRIO-AMORÓS César L. & Denis Alexander TORRES <[email protected]>

Fundación AndígenA, Apdo. Postal 210, Mérida 5101-A Estado Mérida, República Bolivariana de Venezuela

ABSTRACT Following a previous exercise to assess the conservation status of birds in Venezuela, we intend to adapt the

same methodology for amphibians. 91 species of threatened amphibians from Venezuela are assessed and scored under determinate criteria. The results were unexpected, as only four species ranked under the highest priority category. The reasons are discussed.

Key words. Conservation priorities; amphibians; Venezuela.

PRIORIDADES PARA LA CONSERVACIÓN DE LA FAUNA AMENAZADA DE ANFIBIOS DE VENEZUELA.

UNA APROXIMACIÓN PRELIMINAR

RESUMEN Siguiendo los parámetros de un ejercicio previo realizado para las aves en Venezuela, intentamos adaptar la

metodología para anfibios. Contamos 91 especies de anfibios venezolanos amenazados para su puntuación bajo criterios determinados. Los resultados son inesperados, ya que sólo cuatro especies caen bajo el más alto rango de prioridad. Las razones para tal hecho son discutidas.

Palabras clave. Prioridad de Conservación. Anfibios. Venezuela.

INTRODUCTION Amphibians have received lately considerable attention due to its global declines, as a result of many rapid and catastrophic vanishings and local extinctions around the world (Barrio 1996; Barrio-Amorós 2001a, 2001b; 2004; Blaustein & Wake 1995; La Marca 1995; La Marca & Reinthaler 1991; Lampo et al. 2006; Lips 1998; Lips et al. 2006; Pounds et al. 2006; Vial & Sailor 1993; Young et al. 2004). In Venezuela only a few studies about amphibian declination have been made but locally or restricted to one or few species (Lotters et al. 2004; Manzanilla & La Marca 2002; Lampo et al. 2006; Rodriguez et al. 2008). A global understanding and statement of amphibian conservation priorities in this country has been stated lately (Rodríguez & Rojas-Suárez 2008) from subjective appreciations of different specialists. Young et al. (2004) and Stuart et al. (2008) made the first global attempt to assess threats categories to all American amphibians. Venezuela was included with the known species to that moment. We here focus on Venezuelan amphibians following and adapting the methodology of Rodríguez et al. (2004). We will test if this methodology can be applied to assess the global threat to amphibians in Venezuela.

In Venezuela have been several attempts to assess the extinction risk for amphibians. The first one was carried out by Vial & Saylor (1993), followed by La Marca (1995), Rodríguez & Rojas-Suarez (1995, 1999, 2008), Barrio-Amorós (2001a), Young et al. (2004), Barrio-Amorós (in press) and lastly by Molina et al. (2009).

METHODS We focus on 91 species of amphibians that have been stated by Global Amphibian Assessment (GAA) (Young et al. 2004, Rodríguez & Rojas-Suárez 2008 and Barrio-Amorós in press) as lying in one of the following categories of the IUCN Red List: CR= Critically Endangered; EN= Endangered; and VU= Vulnerable. We do not count species considered EX= Extinct, NT= Near Threatened, LC= Low Concern or DD= Data Deficient. In Table 1, 128 species are compared under the scope of the different sources that made some statement about their conservation status.

Rev. Ecol. Lat. Am. Recibido 07 12 2009 Vol 15 Nº1 Art. 3 pp 21- 31 Aceptado 27 02 2010 ISSN 1012-2494 Publicado 30 04 2010 Depósito Legal pp 83-0168 © 2010 CIRES

Ficha BARRIO-AMORÓS César L. & Denis Alexander TORRES, 2010.- Conservation priorities for the most threatened amphibians in Venezuela, a preliminary approach. Rev. Ecol. Lat. Am. 15(1): 21-31 ISSN 1012-2494

BARRIO-AMORÓS César L. & Denis Alexander TORRES

22

Table 1. List of endangered Venezuelan species mentioned by selected sources. The data in this table combine compilations of status from previous sources and first assignments of status to species newly considered as endangered, potentially endangered, or species not considered previously or described after the GAA assessment. The IUCN categories are assigned here by empirical criteria of the IUCN parameters (Young et al. 2004) or on the basis of the senior author's experience. Rodríguez & Rojas Suárez (2008) offer the regional and global red list categories. IUCN abbreviations: DD= Data Deficient; LC= Least Concern; NT= Near Threatened; VU= Vulnerable; EN= Endangered; CR= Critically Endangered; EX= Extinct.

A B C D GAA Young et al. (2004)

Barrio-Amorós (in press)

Rodríguez & Rojas Suárez (2008)

Flectonotus fitzgeraldi

EN B1ab(iii) NT DD/EN B1ab(iii)

Gastrotheca ovifera

X EN B1ab(iii, v) VU B1b(iv) DD/EN B1ab(iii, v)

Prostherapis. dunni

EN B1ab(iii, v) EN/B1ab(iii) DD/CR A2ace

Allobates caribe - VU D2 - A. humilis X VU D2 NT DD/VU D2 A. rufulus DD VU D2 NT/DD Anomaloglossus breweri

- VU D2 -

Aromobates alboguttatus

X X EN B1ab(iii, v)+2ab(iii, v)

CR B1ab(iii, v)+2ab(iii, v)

NT/ENB1ab(iii,v)+2ab(iii,v)

A. capurinensis DD VU D2 DD/DD A. duranti X EN B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii) EN B1ab(iii) DD/ EN B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii)

A. haydeeae X EN B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii, v) EN B1ab(iii) DD/ EN B1ab(iii,v)+2ab(iii,v)

A. leopardalis X X CR A2ace; B2ab(v) CR A2ace; B1ab(iii) DD/CR A2ace; B2ab(v)

A. mandelorum X EN B1ab(iii) EN B1ab(iii) DD/ EN B1ab(iii) A. mayorgai X EN B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii) CR A2ace; B1ab(iii,v) DD/ EN B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii)

A. meridensis X CR B2ab(iii) CR A2ace; B1ab(iii,v) NT/CR B2ab(iii) A. molinarii EN

B1ab(ii,iii)+2ab(ii,iii) EN

B1ab(ii,iii)+2ab(ii,iii) DD/ EN B1ab(ii,iii)+2ab(ii,iii)

A. nocturnus X CR A2a;B2ab(v) CR A2c; B2ab(iii,v) CR A2a; B2ab(v)/ CR A2a; B2ab(v)

A. orostoma X EN B1ab(ii, iii)+2ab(ii, iii)

EN B1ab(ii, iii)+2ab(ii, iii)

DD/ EN B1ab(ii,iii)+2ab(ii,iii)

A. saltuensis X EN B1ab(iii) NT DD/ EN B1ab(iii) A. serranus X EN B1ab(ii, iii)+2ab(ii,

iii) CR A2c; B2ab(iii,v) DD/ EN B1ab(ii,iii)

)+2ab(ii,iii) Mannophryne caquetio

CR B1ab(iii,v)+2ab(ii,v)

CR B1ab(iii,v)+2ab(ii,v)

VU B1ab(iii)/ CR B1ab(iii,v)+2ab(iii,v)

M. collaris X EN B1ab(iii, v)+2ab(iii, v)

VU A3ce DD/ EN B1ab(iii,v)+2ab(iii,v)

M. cordilleriana VU D2 VU D2 DD/ VU D2 M. herminae NT LC NT/ NT M. lamarcai CR B1ab(iii) CR B1ab(iii) EN B1ab(iii)/ CR (B1ab(iii) M. neblina CR/A1ab(v)+2ab(v) CR A1ab(v)+2ab(v) CR B1ab(iv)+2ab(iv)/

CR B1ab(v)+2ab(v) M. yustizi EN/B1ab(iii) VU D2 DD/ EN B1ab(iii)

Conservation priorities for the most threatened amphibians in Venezuela, a preliminary approach

23

Ceuthomantis aracamuni

VU D2 -

C. cavernibardus X DD DD DD/ DD Strabomantis biporcatus

VU/B1ab(iii) NT DD/ VU B1ab(iii)

Dischidodactylus colonnelloi

X DD VU D2 NT/DD

D. duidensis X DD VU D2 NT/DD Pristimantis anolirex

NT DD NT/ NT

P. anotis X DD VU D2 NT/ DD P. avius X DD DD DD/ DD P. bicumulus VU B1ab(iii) NT DD/ VU B1ab(iii) P. boconoensis X CR B1ab(iii) CR B1ab(iii) NT/ CR B1ab(iii) P. briceni VU D2 VU D2 DD/ VU D2 P. cantitans X DD VU D2 DD/ DD P. colostichos X VU D2 VU D2 DD/ VU D2 P. ginesi X EN B1ab(v) VU A2a DD/ EN B1ab(v) P. lancinii X EN B1ab(v) VU A2a DD/ EN B1ab(v) P. marahuaka - VU D2 DD/ VU D2 P. memorans X DD DD DD/ DD P. paramerus X EN B1ab(iii) VU A2a DD/ EN B1ab(iii) P. pruinatus X DD VU D2 DD/ DD P. reticulatus X DD DD NT/ DD P. riveroi X DD LC DD/ DD P. stenodiscus X DD NT DD/ DD P .turumiquirensis

X EN B1ab(iii) DD NT/ EN B1ab(iii)

P. vanadisae NT NT DD/ NT P. yaviensis X DD VU D2 DD/ DD Atelopus carbonerensis

X X X X CR A2ace; B2ab(v) CR A2ace; B1ab(iii,v) CR A2ace; B2ab(v)/ CR A2ace; B2ab(v)

A. chrysocorallus X CR A2ace; B1ab(iii v)+2ab(iii, v)

CR A2ace; B1ab(iii v)+2ab(iii, v)

CR A2ace; B1ab(iii,v)+2ab(i,iii,v)/ CR

A2ace; B1ab(iii,v)+2ab(i,iii,v) A. cruciger X X CR A2ace CR A1ace CR A2ace/ CR A2ace A. mucubajiensis X X X CR A2ace; B2ab(v) CR A2ace; B1b(v) CR A2ace; B2ab(v)/

CR A2ace; B2ab(v) A. oxyrhynchus X X X CR A2ace CR A2c CR A2ace/ CR A2ace A. pinangoi X X CR A2ac; B1ab(iii,v) CR A2ac; B1ab(iii,v) CR A2c; B1ab(iii,v)/

CR A2c; B1ab(iii,v) A. sorianoi X X CR A2ace/B2ab(iii, v) CR A2ce/B2ab(iii, v) CR A2ce; B2ab(iii,v)/

CR A2ce; B2ab(iii,v) A. tamaense X X CR A3ce CR A3ce CR a3ce/ CR a3ce A. vogli EX EX EX/ EX Metaphryniscus sosae

X VU D2 VU D2 NT/ VU D2

Oreophrynella cryptica

X VU D2 VU D2 NT/ VU D2

César L. BARRIO-AMORÓS & Denis Alexander TORRES

24

O. huberi X VU D2 VU D2 VU D2/ VU D2 O. macconelli X VU D2 VU D2 DD/ VU D2 O. nigra X VU D2 VU D2 NT/ VUD2 O. quelchii X VU D2 VU D2 VU D2/ VUD2 O. vasquezi X VU D2 VU D2 VU D2/ VUD2 Rhinella nasica LC DD - R. sternosignata NT LC NT/ NT Allophryne ruthveni

X LC LC

Vitreorana gorzulai

X DD VU D2 DD/ DD

V. antisthenesi VU B1ab(iii) LC NT/ VU B1ab(iii) V. castroviejoi X DD NT NT/ DD Cochranella duidaeana

X DD VU D2 NT/ DD

Celsiella revocata VU B1ab(iii) VU B1ab(iii) DD/ VU B1ab(iii) Cochranella riveroi

X VU D2 VU D2 NT/ VU D2

Celsiella vozmedianoi

X DD VU D2 NT/ DD

Hyalinobatrchium duranti

DD LC DD/ DD

H. fragile VU B1ab(iii) VU B1ab(iii) NT/ VU B1ab(iii) H. guairarepanense

EN B1ab(iii) VU B1ab(iii) EN B1ab(iii)/ EN B1ab(iii)

H. orientale VU B1ab(iii) LC DD/ VU B1ab(iii) H. pallidum EN/B1ab(iii) EN B1ab(iii) DD/ EN B1ab(iii) Ceratophrys calcarata

X LC LC -

Stefania breweri - CR B2a(ii,iv) VU D2/ DD S. ginesi X LC VU D2 NT/ DD S. goini X DD DD NT/ DD S. marahuaquensis

X DD DD DD/ DD

S. oculosa X DD DD NT/ DD S. percristata X DD DD DD/ DD S. riae X DD LC DD/ DD S. riveroi X VU D2 DD VU D2/ VU D2 S. satelles X NT NT NT/ NT S. scalae X LC LC - S. schuberti X VU D2 VU D2 NT/ VU D2 S. tamacuarina X DD DD DD/ DD Dendrobates leucomelas

X LC LC -

Minyobates steyermarki

X CR B2ab(iii) CR B2ab(iii) EN B2ab(iii)/ CR A1c, C2a

Hypsiboas alemani

DD DD DD/ DD

Conservation priorities for the most threatened amphibians in Venezuela, a preliminary approach

25

Dendropsophus amicorum

X CR B1ab(iii) CR B1ab(iii) EN B1ab(ii,III)+2ab(ii,iii)/ CR B1ab(iii)

D. battersbyi DD CR B1ab(iii) DD/ DD D. meridensis X EN B1ab(iii,v) EN B1ab(iii,v) DD/ EN B1ab(iii,v) D. pelidnus LC DD - D. yaracuyanus X DD VU D2 DD/ DD Hyloscirtus jahni X NT NT NT/ NT H. lascinius X LC NT - H. platydactylus X VU A2ace; B1ab(iii,v) NT DD/ VU A2ace; B1ab(iii,v) Hypsiboas rufitelus

LC DD -

H. rythmicus DD VU D2 DD/ DD Myersiohyla aromatica

X DD VU D2 DD/ DD

M. inparquesi X DD VU D2 NT/ DD M. loveridgei X DD DD* DD/ DD Agalychnis medinae

DD CR B2a NT/ DD

Phyllomedusa neildi

- DD -

Scinax manriquei DD LC - Tepuihyla aecii X DD VU D2 NT/ DD T. celsae DD DD DD/ DD T. edelcae X LC NT NT/ DD T. galani X DD VU D2 - T. luteolabris X DD VU D2 NT/ DD T. rimarum X VU D2 VU D2 VU D2/ VU D2 Leptodactylus magistris

X CR B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii) CR B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii) EN B1ab(iii)/ CR B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii)

Otophryne steyermarki

X LC DD -

Bolitoglossa borburata

X X NT VU D2 NT/ NT

B. guaramacalensis

VU D2 VU D2 DD/ VU D2

B. orestes X X VU D2 VU D2 DD/ VU D2 B. spongai X EN B1ab(iii) VU D2 VU D2/ EN B1ab(iii) Microcaecilia rabei

X DD DD DD/ DD

*Only in reference to Venezuelan populations. A: Vial & Saylor (1993); B: La Marca (1995); C: Rodríguez & Rojas Suárez (1995-1999); D: Barrio-Amorós (2001).

We assess the species conservation status following the criteria elected by Rodríguez et al (2004) for birds: the parameters are: 1-extinction risk; 2-degree of endemicity; 3- taxonomic uniqueness; and 4- public appeal. Each parameter was scored from 1 to 3. Multiplying the values assigned to each parameter generates a combined priority score. The priority score has a value between 1-81; understanding the higher scored as the most important species in the scheme. Multiplying the scores rather than summing them give a relative greater weight to the endangered taxa (Rodríguez et al. 2004).

Extinction risk (ER) reflects the urgency of extinction threat (by the IUCN criteria). Species lying into the following categories were scored: Vulnerable (with a value of 1), Endangered (2), and Critically Endangered (3). Taking in count that the last global assessment (Young et al. 2004) and the last national assessments (Rodríguez & Rojas-Suárez 2008; Barrio-Amorós in press) differed considerably, we added all species considered by all lists into one of the three categories, even if one of them does not consider the same species in the other. Only 4 of 91 species are actually non Venezuelan endemics (see next point).

César L. BARRIO-AMORÓS & Denis Alexander TORRES

26

Degree of endemicity (DE) notes the importance of Venezuelan populations with respect of the global range of the species. So, wide ranging species have a score of (1), species distributed through more than one country but within a single Neotropical biogeographic region have (2), and endemic species of Venezuela or which its entire or the greatest part of its population lies in Venezuela are (3).

Taxonomic uniqueness (TU) exposes the evolutionary significance of the species in terms of divergence with close relatives. Species of large genera (more than 11 species) has

(1); medium sized genera (2-10 species) have (2); and a monoespecific genus has (3). This case is actually difficult to assess, done the current phylogenies (Faivovich et al. 2005; Frost et al. 2006; Grant et al. 2006; Heinecke et al. 2007) that removed all classical amphibian systematic (Frost 1985; Duellman 1993) with many authors not comfortable with them. It is quite difficult to follow one of the proposed systematics without falling in possible errors of interpretation. However, in this work we follow the most recent accounts in order to agree with much workers and conservationists.

Table 2. Species of amphibians included in this analysis, from both Lists (GAA 2004; Barrio-Amorós, in press) with its ranking parameters and priority scores. See abbreviations in the method section.

Species Parameter scores

Biogeographic region

ER DE TU PA Priority score

Flectonotus fitzgeraldi 2 2 2 1 8 CC

Gastrotheca ovifera 2 3 1 1 6 CC

Prostherapis dunni 2 3 3 1 18 CC

Allobates caribe 3 3 1 1 9 CC

A. humilis 3 3 1 1 9 AND

A. mandelorum 2 3 1 1 6 CC

A. rufulus 3 3 1 1 9 GS

Anomaloglossus breweri 3 3 1 1 9 GS

Aromobates alboguttatus 3 3 1 1 9 AND

A. capurinensis 3 3 1 1 9 AND

A. duranti 2 3 1 1 6 AND

A. haydeeae 2 3 1 1 6 AND

A. leopardalis 3 3 1 1 9 AND

A. mayorgai 3 3 1 1 9 AND

A. meridensis 3 3 1 1 9 AND

A. molinarii 2 3 1 1 6 AND

A. nocturnus 3 3 1 2 18 AND

A. orostoma 2 3 1 1 6 AND

A. saltuensis 2 2 1 1 4 AND

A. serranus 2 3 1 1 6 AND

Mannophryne caquetio 3 3 1 1 9 CC

M. collaris 2 3 1 1 6 AND

M. cordilleriana 1 3 1 1 3 AND

M. lamarcai 3 3 1 1 9 CC

M. neblina 3 3 1 1 9 CC

M. yustizi 2 3 1 1 6 AND

Strabomantis biporcatus 1 3 1 1 3 CC

Dischidodactylus colonnelloi

1 3 2 1 6 GS

Conservation priorities for the most threatened amphibians in Venezuela, a preliminary approach

27

D. duidensis 1 3 2 1 6 GS

Pristimantis anotis 1 3 1 1 3 CC

P. aracamuni 1 3 1 1 3 GS

P. bicumulus 1 3 1 1 3 CC

P. boconoensis 3 3 1 1 9 AND

P. briceni 1 3 1 1 3 AND

P. cantitans 1 3 1 1 3 GS

P. colostichos 1 3 1 1 3 AND

P. ginesi 2 3 1 1 6 AND

P. lancinii 2 3 1 1 6 AND

P. marahuaka 1 3 1 1 3 GS

P. paramerus 2 3 1 1 6 AND

P. pruinatus 1 3 1 1 3 GS

P. turumiquirensis 2 3 1 1 6 CC

P. yaviensis 1 3 1 1 3 GS

Atelopus carbonerensis 3 3 1 3 27 AND

A. chrysocorallus 3 3 1 2 18 AND

A. cruciger 3 3 1 3 27 CC

A. mucubajiensis 3 3 1 3 27 AND

A. oxyrhynchus 3 3 1 2 18 AND

A. pinangoi 3 3 1 2 18 AND

A. sorianoi 3 3 1 2 18 AND

A. tamaense 3 2 1 2 18 AND

Metaphryniscus sosae 1 3 3 1 9 GS

Oreophrynella cryptica 1 3 2 1 6 GS

O. huberi 1 3 2 1 6 GS

O. macconelli 1 3 2 1 6 GS

O. nigra 1 3 2 1 6 GS

O. quelchii 1 3 2 1 6 GS

O. vasquezi 1 3 2 1 6 GS

Vitreorana gorzulai 1 3 1 1 3 GS

Vitreorana antisthenesi 1 3 1 1 3 CC

Cochranella duidaeana 1 3 1 1 3 GS

Celsiella revocata 1 3 1 1 3 CC

Cochranella riveroi 1 3 1 1 3 GS

Celsiella vozmedianoi 1 3 1 1 3 CC

Hyalinobatrachium fragile

1 3 1 1 3 CC

César L. BARRIO-AMORÓS & Denis Alexander TORRES

28

H. guairarepanensis 2 3 1 1 6 CC

H. orientale 1 3 1 1 3 CC

H. pallidum 2 3 1 1 6 AND

Stefania breweri 3 3 2 1 18 GS

S. ginesi 1 3 2 1 6 GS

S. riveroi 1 3 2 1 6 GS

S. schuberti 1 3 2 1 6 GS

Minyobates steyermarki 3 3 3 3 81 GS

Dendropsophus amicorum

3 3 1 1 9 CC

D. battersbyi 3 3 1 2 18 CC

D. meridensis 2 3 1 1 6 AND

D. yaracuyanus 1 3 1 1 3 CC

Hyloscirtus platidactylus 1 3 1 1 3 AND

Hypsiboas rythmicus 1 3 1 1 3 GS

Myersiohyla aromatica 1 3 2 1 6 GS

M. inparquesi 1 3 2 1 6 GS

Agalychnis medinai 3 3 2 1 18 CC

Tepuihyla aecii 1 3 2 1 6 GS

T. galani 1 3 2 1 6 GS

T. luteolabris 1 3 2 1 6 GS

T. rimarum 1 3 2 1 6 GS

Leptodactylus magistris 3 3 1 1 9 CC

Bolitoglossa borburata 1 3 1 1 3 CC

B. guaramacalensis 1 3 1 1 3 AND

B. orestes 1 3 1 1 3 AND

B. spongai 2 3 1 1 6 AND

Biogeographic regions considered following Barrio-Amorós (1998) are as follows: AND= Andes; CC= Coastal Chain; GS= Guiana Shield.

Public appeal (PA) is very difficult to assess in amphibians. Birds, otherwise, are animals more recognized and popular among humans. Usually humans have more care of beautiful and/or charismatic species (parrots and macaws, bears, etc) than to amphibians and reptiles. There is not social awareness about reptiles and amphibians. Although probably all species of amphibians would obtain a score of (1) meaning that they do not attract particularly the interest of the general public, we subjectively give (2) to species that probably would attract the public attention, and (3) the species we consider that after a proper campaign would really interest the general public.

The geographical distribution is assessed by presence/absence of the following bioregions important to amphibians (following Barrio-Amorós 1998): Andes; Coastal Chain; Llanos; Amazon basin; Guiana shield; Orinoco Delta; Maracaibo lake region. The number of threatened species was determined for each bioregion and mean priority scores were calculated by averaging the scores of the species present.

The priority of the bioregions is scored in terms of number of threatened amphibian species.

RESULTS

Four groups of species were identified: those lying into the following categories: Highest, High, Medium and Low Priority (Table 2). Those lying in the highest priority category are those with a score of 27 or more. Four species fall in this group.

Of High Priority are those species with 18 points. 10 species are considered.

Medium Priority contains those species with 9 points, which are 15.

Finally, the rest of species (62), ranked with 8 or less, are considered of Low Priority.

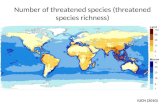

Biogeographically, only three of the seven bioregions known to be important for amphibians (Barrio-Amorós 1998) are

Conservation priorities for the most threatened amphibians in Venezuela, a preliminary approach

29

represented: Andes, Coastal Chain and Guiana Shield. Although this last is a vast region encompassing lowlands, uplands and highlands (sensu Huber 1995 and Gorzula & Señaris 1999), all species here considered from that region come from highlands, usually tepui summits. 35 threatened species are from the Andes (38.4%); 25 comes from the Coastal Chain (27.4%); and 31 (34%) are from the Guiana Shield.

DISCUSSION

Priority species Only three species of Atelopus (A. carbonerensis, A. cruciger and A. mucubajiensis) reach 27 points. This is due to the fact that, even considered generally as the most important genus to protect and study, the genus Atelopus has more than 80 species and it does not rank under TU parameter . Thus, that parameter could be not be very proper to consider in further or next exercises, at least for amphibians. We still consider that Atelopus should be the top priority genus to work on conservation projects.

The highest ranked species is, contrary to expected, the demonic poison frog Minyobates steyermarki, ranking 81. This can be explained easily taking in count that it pertains to a monotypic genus (according to current taxonomy, although could change in future investigations), it is considered by both lists as CR, it is endemic from a small tepui in the Venezuelan Amazon, and that would be an appropriate candidate for a public awareness campaign, done its beauty and attractive. Indeed, Cerro Yapacana, a small and isolated tepui (sandstone table mountain typical from the Guiana Shield) theoretically protected under the figure of National Park Yapacana, is being destroyed implacably by illegal gold miners that put in danger the entire ecosystem (Barrio & Fuentes 1999). Also, due to its small and highly restricted endemic population on the top and slopes of that remote tepui, it is highly vulnerable to illegal extraction, as happened at least once (Barrio & Fuentes 1999) and possibly more times.

Stefania breweri (score 18) is a restricted endemic from the top of Cerro Autana, a small tepui with a summit area of 1.88 km². Unfortunately little is known about this species, and even there is no information about its living coloration and habits. Its remote location, possibly not bright coloration and impossibility to reach the place makes it not a candidate for a public campaign.

Dendropsophus battersbyi (18) is a small species of treefrog described from Caracas (Rivero 1961). Due to the quickly transformed habitat it probably has become extinct, but no attempt has tried to search it based on a serious methodology. Probably through a well focused campaign the “Caracas tree frog” would awake the public interest and be financed for a monitoring program.

Agalychnys medinai (18) is one of the most pretty and attractive endangered species in Venezuela. It could be an easy subject of a well prepared campaign. It apparently disappeared from its type locality (Rancho Grande at Henri Pittier National Park) but was again encountered in two close localities in Carabobo and Yaracuy states (Proy 2000; Lotzkat et al. 2007). Its population is still unknown.

We do not agree with all of these results. Many are due to follow the recent systematic accounts cited before. For example, prior to the dendrobatid phylogeny by Grant et al. (2006), Aromobates nocturnus was a species in a monotypic genus that would be scored as 54 instead 18; currently many Andean species of former Colostethus also integrates the same genus Aromobates.

On the other hand, “Prostherapis” dunni, a bad known species from the Coastal Chain, is ranked 18 only because the taxonomic status is unknown and it is monotypic at this time, waiting for a comprehensive study of its relationships. Its probable score if fitting some already known genera of Aromobatidae should descend to 6 or 12.

There is a notable problem scoring amphibians for PA. Many species that cannot be of interest for the general public actually needs an urgent response by scientists, like Aromobates alboguttatus A. leopardalis, and A. meridensis (all scoring 9).

Geographically, we found that 8 ranked species (those with 18 or more points) are from the Andes, while 4 are from the Coastal Chain, and two are from the Guiana Shield.

RECOMMENDATIONS

With the new data at hand, should be clear that Minyobates steyermarki is the most ideal species to work as representant of the most critical endangered Venezuelan amphibians. However, it lives in such remote location that only a minimum part of the Venezuelans know, and a campaign defending its survival would be probably worthless. Of course this doesn’t means that would be not interesting to try, especially taking in count that Yapacana is being destroyed illegally by gold mining inside a National Park.

But most properly, and coinciding with the last avalanche of information focused on the genus Atelopus (Rueda-Almonacid et al. 2005; La Marca et al. 2005), we agree in that these eight species must be actively searched, and monitored if extant, in order to proceed with the international initiatives that try to find solutions to several problems that these frogs face.

The same is valid to apply to those mentioned species that can be monitored if some populations are encountered, like Dendropsophus battersbyi, Prostherapis dunni, Agalychnys medinai, Aromobates nocturnus, A. alboguttatus, A. meridensis and A. leopardalis. Stefania breweri lives in such remote and inaccessible area that makes impossible any chance to monitor its population. Only if the next expedition to Autana is made with the objective to look for this species, a number could be calculated.

So far, we highly recommend to international and national financing organizations to invest in the aforementioned species as a high priority agenda of their activities.

On the other hand, we also propose to score the endangered Venezuelan amphibians under other criteria, possibly showing a different result from this exercise.

LITERATURE CITED BARRIO, C. L. 1996. Atelopus, ¿sólo un recuerdo?

Reptilia 8: 26-28.

César L. BARRIO-AMORÓS & Denis Alexander TORRES

30

BARRIO-AMORÓS, C. L. 1998. Sistemática y Biogeografía de los anfibios (Amphibia) de Venezuela. Acta Biol. Venez. 18(2): 1-93.

BARRIO-AMORÓS, C. L. 2001a. Some aspects of dendrobatids in Venezuela: declines and nomenclature. British Dendrobatid Group Newsletter 44: 1-5.

BARRIO-AMORÓS, C.L. 2001b. State of knowledge on the declination of amphibians in Venezuela. FROGLOG 47: 2-4.

BARRIO-AMORÓS, C. L. 2004. Atelopus mucubajiensis still survives in the Andes of Venezuela. Preliminary report. FROGLOG 66: 2-3.

BARRIO-AMORÓS, C. L. in press. Status of Amphibian conservation and decline in Venezuela. In: Decline in amphibians: Western hemisphere. Amphibian Biology. (Heatwole, H., C.L. Barrio-Amorós, & J. Wilkinson Eds.): Volume 8B.

BARRIO, C. L., & FUENTES, O. 1999. Sinopsis de la familia Dendrobatidae (Amphibia: Anura) de Venezuela. Acta Biol. Venez. 19 (3): 1-10.

BLAUSTEIN, A. R., & WAKE, D. B. 1995. Declive de las poblaciones de anfibios. Investigación y Ciencia 1995 (Junio): 8-13.

DUELLMAN, W. E. 1993. Amphibian Species of the World. Additions and corrections. Univ. Kansas Mus. Nat. Hist. Spec. Publ., 21: 372 pp.

FAIVOVICH, J., C. F. B. HADDAD, P. C. A. GARCÍA, D. R. FROST, J. A. CAMPBELL & W. C. WHEELER. 2005. Systematic Review of the Family Hylidae with special reference to Hylinae: Phyllogenetic Analysis and Taxonomic Revision. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 294: 1-240.

FROST, D. R. (ed.). 1985 Amphibian Species of the World. Allen Press Inc. & Association of Systematic Collections, Lawrence, Kansas, USA. 732 pp.

FROST, D. R., GRANT, T., FAIVOVICH, J., BAIN, R. H., HAAS, A., HADDAD, C. F. B., DE SÁ, R. O., CHANNING, A., WILKINSON, M., DONNELLAN, S. C., RAXWORTHY, C. J., CAMPBELL, J. A., BLOTTO, B. L., MOLER, P., DREWES, R. C., NUSSBAUM, R. A., LYNCH, J. D., GREEN, D. M. & WHEELER, W. C. 2006. The Amphibian Tree of Life. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 297: 1-370.

GORZULA, S. & SEÑARIS, J.C. 1998. Contribution to the herpetofauna of the Venezuelan Guayana. I. A data base. Scientia Guaianae 8: 267 pp.

GRANT, T., D.R. FROST, J. P. CALDWELL, R.GAGLIARDO, C.F.B. HADDAD, P.J.R.KOK, D.B.MEANS, B.P.NOONAN, W.E.SCHARGEL & W.C.WHEELER. 2006. Phylogenetic systematics of dart-poison frogs and their relatives (Amphibia: Athesphatanura: Dendrobatidae). Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 299: 1-262.

HEINICKE, M.P., W.E. DUELLMAN & S.B. HEDGES. 2007. Major Caribbean and Central American frog faunas originated by ancient oceanic dispersal. PNAS 104(24): 10092-10097.

HUBER, O. 1995. Geographical and physical features. In: Flora of the Venezuelan Guayana (J.A. Steyermark, P.E. Berry, and B.K- Holst, gen. eds), Vol. I, Introduction (P.E.Berry, B.K. Holst and K. Yatskievych, eds.), pp 1-61. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis; Timber press, Portland, Oregon.

LA MARCA, E. 1995. Crisis de biodiversidad en anfibios de Venezuela: estudio de casos. Pp. 47-70, in “La Biodiversidad Neotropical y la Amenaza de las Extinciones”, (M. Alonso Ed.) Cuad.-Quim. Ecol. 4, Fac. Cienc. ULA, Mérida 47.

LA MARCA, E. & H. P. REINTHALER. 1991. Population changes in Atelopus species of the Cordillera de Mérida, Venezuela. Herp. Review 22: 125-128.

LA MARCA, E., K. R. LIPS, S. LÖTTERS, R. PUSCHENDORF, R IBÁÑEZ, J.V. RUEDA-ALMONACID, R. SCHULTE, C. MARTY, F. CASTRO, J. MANZANILLA, J. E. GARCÍA, F. BOLAÑOS, G. CHAVES, J. A. POUNDS, E. TORAL, & B. E. YOUNG. 2005. Catastrophic Population Declines and Extinctions in Neotropical Harlequin Frogs (Bufonidae: Atelopus). Biotropica 37(2): 190–201.

LAMPO, M., A. RODRÍGUEZ, E. LA MARCA & P. DASZAK. 2006. A Chytridiomycosis epidemic and a severe dry season precede the disapperance of Atelopus species from the Venezuelan Andes. Herp. J. 16: 395-402.

LIPS, K. R. 1998. Decline of a tropical montane amphibian fauna. Cons. Biol. 12: 106-117.

LIPS. K.R., F. BREM, R. J. BRENES,.D. REEVE, R.A. ALFORD, J. VOYLES, C. CAREY, L. LIVO, A.P. PESSIER, & J.P. COLLINS. 2006. Emerging infectious disease and the loss of biodiversity in a Neotropical amphibian community. PNAS 103(9): 3165-3170.

LÖTTERS, S., E. LA MARCA & M. VENCES. 2004. Redescription of two toad species of the genus Atelopus from Coastal Venezuela. Copeia 2004 (2): 222-234.

LOTZKAT, S., A. HERTZ, & J. VALERA-LEAL. 2007. Amphibia, Anura, Hylidae, Hylomantis medinai: Distribution extension by discovery of a third population. Checklist 3: 200-203.

MANZANILLA, J. & E. LA MARCA. 2002. Museum records and field sampling as sources of data indicating population crashes for Atelopus cruciger, a proposed critically endangered species from the Venezuelan Coastal range. Mem. Fund. La Salle Cien. Nat. 157: 5-30.

MOLINA, C., J.C. SEÑARIS, M. LAMPO, & A. RIAL. 2009. Anfibios de Venezuela; Estado del conocimiento y recomendaciones para su conservación. Ediciones Grupo TEI, Caracas: 130 pp.

POUNDS, J.A., M.R. BUSTAMANTE, L.A. COLOMA, J.A. CONSUEGRA, M.P.L. FOGDEN, P.N. FOSTER, E. LA MARCA, K.L. MASTERS, A. MERINO-VITERI, R. PUSCHENDORF, S.R. RON, G.A. SÁNCHEZ-AZOFEIFA, C.J. STILL & B.E. YOUNG.

Conservation priorities for the most threatened amphibians in Venezuela, a preliminary approach

31

2006. Widespread amphibian extinctions from epidemia disease driven by global warming. Nature 439: 161-167.

PROY, C. 2000. Neue daten zu Verbreitung und Entwicklung von Phyllomedusa medinai Funkhouser, 1962. Herpetofauna 22(126): 19-22.

RIVERO, J. A. 1961. Salientia of Venezuela. Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool., 126 (1): 1-267.

RODRÍGUEZ-CONTRERAS, A., C.J. SEÑARIS, M. LAMPO & R. RIVERO, 2008.- Rediscovery of Atelopus cruciger (Anura: Bufonidae): current status in the Cordillera de la Costa, Venezuela. Oryx 42(2): 1-4.

RODRÍGUEZ, J. P. & F. ROJAS-SUÁREZ. 1995. Libro Rojo de la Fauna Venezolana. 2da. edición. PROVITA, Fundación Polar. Caracas, Venezuela. 444 pp.

RODRÍGUEZ, J. P. & F. ROJAS-SUÁREZ. 1999. Libro Rojo de la Fauna Venezolana. 2da. edición. PROVITA, Fundación Polar. Caracas, Venezuela. 472 pp.

RODRÍGUEZ, J. P. & F. ROJAS-SUÁREZ. 2008. Libro Rojo de la Fauna Venezolana. 3a. edición. PROVITA y Shell Venezuela, S.A., Caracas, Venezuela: 364 pp.

RODRIGUEZ, J. P., F. ROJAS-SUÁREZ, & C. SHARPE (2004) Setting priorities for the Conservation of Venezuela’s threatened birds. Oryx, 38(4): 373-382.

RUEDA-ALMONACID, J. V., J. V. RODRÍGUEZ-MAHECHA, E. LA MARCA, S. LÖTTERS, T. KAHN, A. ANGULO (Eds.). 2005. Ranas arlequines. Serie Arca de Noe. Conservación Internacional: 158 pp.

STUART, S.N., M. HOFFMAN, J. CHANSON, N. COX, R. BERRIDGE, P. RAMANI, & B. YOUNG (Eds.). 2008.- Threatened Amphibians of the World. Lynx Editions, Barcelona, Spain; IUCN, Gland. Switzerland; Conservation International, Arlington, Virginia, U.S.A.

VIAL, J. L., & L., SAYLOR. 1993.- The status of amphibian populations. A compilation and analysis. IUCN/SSC DAPTF. Working Document 1: 1-98.

YOUNG, B. E., S. N. STUART, J. S. CHANSON, N. A. COX & T. M. BOUCHER 2004.- “Disappearing Jewels: the Status of New World Amphibians”. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia.

Adress BARRIO-AMORÓS César L. & Denis Alexander TORRES [email protected] www.andigena.org Fundación AndígenA, Apdo. Postal 210, Mérida 5101-A, Estado Mérida, República Bolivariana de Venezuela.