Conquering Limits

-

Upload

simon-melanson -

Category

Documents

-

view

230 -

download

0

Transcript of Conquering Limits

CA

NA

DIA

N C

OA

ST G

UA

RD

– EC

HO

– SE

PTE

MB

ER

2015

by Simon Melanson

CONQUERING LIMITS, ONE STEP AT A TIME

continued on page 32

NOW! Your contribution is invaluable and will help make DFO a thriving and resilient workplace!

To be added to the Network’s distribution list or to inquire into how you can get more involved, please send an e-mail to the group at [email protected].

You can start learning about DFO’s YPN right away by joining the DFO-YPN’s GCConnex page, which serves as the primary forum for members to communicate with each other. Once on GCConnex, introduce yourself by replying to the “Introduce yourself” thread! Also, check out the DFO YPN’s GCPedia page for further information on how to join the Network!

Last October, I set out on a journey to complete the Atacama Crossing: a 7-day, 250 km, self-supported footrace across the driest, highest, and oldest desert in the world. I was one of 163 competitors that took to the start line and among the 119 who made it to the finish a week later. I ran and climbed until I collapsed, felt indescribable physical agony and mental anguish. But, in the process of training for and completing the race, I discarded every limit I had ever placed on myself and was reminded that leading a good life requires taking risks and lots of persistence.

4 Deserts

The Atacama Crossing is part of the 4 Deserts: a rough-country endurance footrace series that takes place over seven days and 250 kilometers in the most forbidding deserts on the planet (Atacama, Gobi, Sahara, and Antarctica). The series was recently named again by

TIME magazine as one of the Top 10 Endurance Competitions in the world. Basically, competitors race through the most inhospitable climates and landscapes, carrying all of the equipment and food they need to survive for seven days and nights, and are only provided with drinking water and an old canvas tent with nine other snoring people.

Training

I had been running competitively long enough to know that the Atacama Crossing was going to be my Hell Week (reference to US Navy SEAL training). I knew that at best, the race would test my mental and physical resilience; at worst, I would quit, be injured, or even die.

I was prepared to do whatever it took to succeed but I wasn’t sure where to start. So, I called up one of the greatest ultrarunners in the world, and Ottawa native, Ray Zahab. In the span of just a decade, Ray has run across nearly every part of the world. In 2007, he ran across the Sahara Desert in 111 days, a voyage that was chronicled in the documentary Running the Sahara narrated and produced by Matt Damon. In 2011, Ray became the first person to cross the entire Atacama Desert from north to south on foot. He had the expertise I was after. During our first conversation, Ray said “OK. You sound pretty serious. I am willing to coach you but you have to do everything I tell you. Otherwise, you won’t be ready.” I agreed without hesitation.

Ray gave me a structured training plan that included nutrition, strength training, altitude training, and diverse running assignments. In the 18 months leading up to the race, I ran over 3,500 kilometres on all kinds of terrain. (Roughly equivalent to running from the

31

The Atacama Desert is the driest place on Earth, located on a plateau in the “rain shadow” between the Andes and Chile’s

Coastal Range. (Photo Credit: Thiago Diz)

CA

NA

DIA

N C

OA

ST

GU

AR

D –

EC

HO

– S

EP

TEM

BE

R 2

015

continued from page 31

CCG base in Dartmouth, N.S. to USCG base in Key West, FL; or from the CCG Base in Victoria to Cabo San Lucas, Mexico). Training was different every day. On weekdays, I would often wake up in the wee hours of the morning and run a half marathon (21.1 km) and occasionally a full marathon (42.2km) before eating breakfast, bringing my kids to school, and heading to the office.

On other days, I did 20 minutes of hill sprints or, hit the gym for 45 minutes of heavy lifting. During evenings, I usually did intermittent hypoxic training using an altitude machine. Weekends were reserved for race simulation: 4-5 hour (40km) runs through the forest trails in Gatineau Park with a 20lbs pack. Rain or shine, snow or sleet, muscle strains or black bears—I just kept running and digging deeper.

A certain amount of tension is unavoidable between a coach and a client. I recall last July; I was losing interest in many of the running assignments Ray was giving me. I had logged roughly 3,000 kilometers to this point and I was feeling fed up. Ray said “No problem. I will give you a short assignment this weekend.” He sent me for a 10km run on a network of old forest fire-fighting trails along the Eardley Escarpement that date back to the 1950s and 60s. I brought along the hand written map Ray had scribbled out on a stub of paper. Less than 1 km into the run, a torrential downpour dissolved the map into a crumpled ball in my hands. I spent

the next two hours bushwhacking through dense forest doing 300m climbs and steep, slippery descents. After clearing eight kilometers of trail, mostly with my face, and falling several times, I emerged at the foot of the escarpment in a swamp with all of the wonderful wildlife it supported. I spent the final two kilometres of my run traipsing through knee-deep water and cutting down cattails with my arms. By the time I found my car, I was covered in mud, cuts, bruises, and a couple of leeches. I immediately called Ray and gave him hell. After hearing me out, he simply said, “Ultra running is far from the limelight of other sports. More than 5,000 people have summited Mt. Everest

but fewer than 1,000 people have completed the Atacama Crossing. There’s a reason for that; it’s tough! Go home, take a hot shower, and call me tomorrow.”

The Atacama Desert

Ray’s tough love prepared me well for my race, both physically and mentally. The Atacama Desert is otherworldly; straight out of a science fiction novel set on Mars. It is dominated by vast

plains of rock, sand, and silt; punctuated by volcanoes, lava flows, mountains, salt basins, and skyscraper-sized sand dunes. The average elevation is 4 kilometers (13,100 feet) above sea level, making it

the highest desert in the world. Cloud cover is almost non-existent and the UV index is extreme (+11). Daytime temperatures can exceed 40°C and nighttime temperatures dip below freezing. At the center of the Atacama, is a place climatologists call “absolute desert.” It is a sterile, lifeless place where rain has never been recorded, at least as long as

Sunrise at Camp 1: -1oC, 3,500m above sea level, under the watchful eye of spooky geological formations. (Photo Credit:

Thiago Diz)

32

Many competitors drop out of the race due to exhaustion and injuries. This

competitor lost his heel and part of the sole of his foot. (Photo credit: Thiago

Diz)

CA

NA

DIA

N C

OA

ST G

UA

RD

– EC

HO

– SE

PTE

MB

ER

2015CA

NA

DIA

N C

OA

ST

GU

AR

D –

EC

HO

– S

EP

TEM

BE

R 2

015

continued on page 34

humans have measured it. There isn’t a blade of grass, a cactus stump, not a lizard, not a gnat. In brief, the Atacama is starkly beautiful, but an intensely inhospitable place.

My Race

There were many hours of suffering interspersed with moments of awe, despair, panic, and euphoria. Running a marathon a day at altitude, in blazing sun, with a pack, over terrain that is rarely flat underfoot, is a grueling challenge for even the world’s most elite runners (which I am not). Most of the time I thought “Mother Nature is an evil witch that wants me dead.” I knew this, I accepted it, and tried to stomp on at least one plant every day as petty revenge against her for it—except there were almost none.

On Day 1 of the race, I tore my abdominal muscles during a fall near the edge of a cliff. I thought my race was over but somehow carried on. On Day 2, I ran out of water, collapsed in the midday sun, and thought I would never get back on my feet. On Day 3, I

encountered terrain so blatantly designed to do nothing but destroy the human beings in the most awful ways possible, that I couldn’t help but stand and applaud Mother Nature’s sheer bravado. On Day 4, I ran across the infamous “salt flats”. There was nothing flat about them; they were more like the Earth’s cement-coral teeth, designed to stab and

grind the feet of competitors into a fleshy pulp for easy digestion.

Day 5 was the Long March: an 80km Odyssey through the highs and lows of the Atacama Desert. I saved most of the battery power in my iPod for

this day. I blasted Daft Punk as I confronted sand dunes hundreds of feet high and ran through endless stony plains. My feet, legs, and eventually my whole body, went numb from repetitive foot strikes. Crossing the finish line on Day 5 was dreamlike. A blood test painted a picture of me with diseased organs and biological decay owing to chemical compounds tossed off by my skeletal muscle, heart, and liver during five consecutive days of exertion. My feet were swollen, crammed into ill-fitting shoes that

were a full size larger than what I had trained with back in Canada. All of my toenails were shattered and some fell off when I removed my socks. And the chafing from my pack had gone from being a nuisance to Halloween-level gore. But, I didn’t care. I felt boundless. I had successfully broken the back of the race. Few kilometres remained.

Day 6 and 7 were a blur. I mostly thought of the different foods I would eat once I was back in civilization. As I ran from the vast open desert into the narrow mud walled streets of San Pedro de Atacama on Day 7, and crossed the final finish line of the race, a surreal feeling came over me. I felt a like I was in a first-person shooter video game. Like I had been sniped, and the entire race had been compressed into a few seconds of animation of me

Simon Melanson (right) his wife, Dawn (left) and daughters Olivia and Grace (middle) at

the finish line in San Pedro de Atacama. (Photo credit: Joe Mauko)

33

These were brand new seven days ago! The extreme

conditions of the Atacama shredded and melted the

treads off my shoes. (Photo credit: Simon Melanson)

CA

NA

DIA

N C

OA

ST

GU

AR

D –

EC

HO

– S

EP

TEM

BE

R 2

015

continued from page 33

dying, the screen faded to black, and then I was right back where I started. I was in a complete daze. Then I heard the voices of my wife and daughters. My brain stirred…this was real…the race was actually over.

Why?

Without a doubt, the most frequent question I heard from others is “Why do this?” “Why can’t you just be content to lounge by the pool or sit in a café?” Good questions. On a personal level, I don’t have a dimmer switch. I live my life to have good stories. I am also a disciplined, persistent person. I believe in my goals, all the time, every time. I am also blessed to have a family and a network of friends and colleagues that support me in my various crazy endeavours. But, all this begs larger questions. “Why did the 118 other tremendous competitors that finished the same race do it?” “Why do any of us do anything hard?

Ask this question enough and I believe that the answer you will hear most often is that taking positive, calculated risks and being persistent are necessary to achieve anything great in life. This is true 100 percent of the time but, we sometimes forget or even ignore this truth. We all live ordinary

lives until we find a compelling reason to succeed and energize our body and minds for success. Then it becomes a good story.

Postscript

Simon Melanson is Director of Maritime Security and Incident Management.

In conjunction with his race across the Atacama Desert, Simon founded the Simon Melanson Help Lesotho Project to help children infected and/or affected by HIV/AIDS in Lesotho, Southern Africa. He raised $13,000 to send 78 children orphaned by HIV/Aids to leadership camp and build a new playground in the north of the country. The playground is one of the only playgrounds in the north of Lesotho and was finished at the end of April 2015. The Leadership Camp was held in June 2015. A heartfelt thank you to all those at CCG, and beyond, that made these two projects possible.

Simon’s Desert Blog – Entertaining posts from Simon’s time racing through the Atacama Desert. Available at: http://www.4deserts.com/blogs/ac_comptetior_blog.php?pid=MjQzNw%3D%3D&blog=124

34

The Simon Melanson Help Lesotho Project raised funds to send 78 high school students in

Lesotho to Leadership Camp and build a new playground in the remote northern part of the

country. (Photo credit: Help Lesotho)

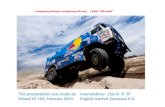

Go Canada Go! Five Canadians finished in the Top 20 at the 2014 Atacama Crossing, including Simon Melanson (middle), Jean-François Bégin (left) and Claude Bégin (right). (Photo

Credit: Dawn Melanson)