Conceiving Musical Transdialection2BMusical%2BDialection.pdfBach–Busoni: In 1907, Feruccio Busoni...

Transcript of Conceiving Musical Transdialection2BMusical%2BDialection.pdfBach–Busoni: In 1907, Feruccio Busoni...

RICHARD BEAUDOIN AND JOSEPH MOORE

Conceiving Musical Transdialection

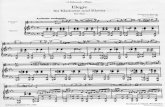

While it may not surprise you to learn that the firstbit of music above is the opening of a chorale pre-lude by Baroque master Johann Sebastian Bach,who would guess that the second bit is a transcrip-tion of it? But it is—it is a transcription by the con-temporary British composer Michael Finnissy.1

The two passages look very different from oneanother, even to those of us who do not read mu-sic. And hearing the pieces will do little to dispelthe shock, for here we have bits of music thatseem worlds apart in their melodic makeup, har-monic content, and rhythmic complexity. It is a farcry from Bach’s steady tonality to Finnissy’s float-ing, tangled lines—a sonic texture in which, as one

critic put it, real music is “mostly thrown into aseething undigested, unimagined heap of dyslexicclusters of multiple key- and time-proportions, asintricately enmeshed in the fetishism of the writtennotation as those with notes derived from number-magic.”2 We are more sympathetic to Finnissy’smusic. But still, how can one maintain that hismusic transcribes Bach’s? What conceptual un-dertaking and what art-historical trajectory canproduce such a relationship without straining theterm ‘transcription’ past its useful limits?

In this article, we illuminate the wandering no-tion of musical transcription by reflecting on thevarious ways ‘transcription’ and its cognates have

The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68:2 Spring 2010c! 2010 The American Society for Aesthetics

106 The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism

been used in musical discourse (Section I). Atroot, musical transcription aims at preservation,though as we bring out, exactly which musical in-gredients are preserved across which transforma-tions varies from transcriptional project to tran-scriptional project. In fact, our primary goal is touncover, articulate, and endorse one very interest-ing such project—we call it “transdialection”—inwhich a transcriber reexpresses a work in a dif-ferent musical dialect. We sketch the emergenceof this fruitful musical undertaking by examiningsome notable twentieth-century Bach transcrip-tions, including Finnissy’s, which became increas-ingly loose through the decades (Section II). Wesharpen our understanding of this new species oftranscription by exploring an analogy with poetictranslation (Section III) and by responding to sev-eral objections (Section IV). We conclude, amongother things, that Finnissy’s transcription is justifi-ably and usefully so called. And we suggest waysin which our notion of transdialection might be ex-tended to illuminate other artistic practices (Sec-tion V).

i. “transcription” traversed

The word ‘transcription’ is used in several waysin musical discourse. It is worth introducing someterminology so that we can set apart the notion—“musical transcription”—that we aim to illuminateas well as to show how, at root, transcriptions inall senses aim at preservation. “Notational tran-scription” is the process of renotating a musicalwork—that is, of notating in a new form a previ-ously notated work, as when a piece written intablature is transcribed to staff notation, or whena trumpet part in C is transcribed to be played on atrumpet in B-flat. Notational transcription aims topreserve a musical work across some difference innotational form, and it can be carried off withoutactually listening to the work itself. “Ethnomusi-cological transcription” is the process of writingdown or notating music that is heard in live per-formance or on a recording. This might be donein an effort to preserve the music of some cul-ture or musician for enthnomusicological study;but it might also be done for musical education,as when an aspiring jazz musician transcribes animprovised solo from a recording.3

While notational transcription aims to preservemusic across differences in notation, and ethno-musicological transcription aims to preserve mu-sic in a notated form, what we call “musical tran-scription” aims to preserve the expressive contentof a musical work across some difference in musi-cal context. Determining just what differences canlegitimately engage a project of musical transcrip-tion is the central concern of this article. But theparadigm case is the attempt to preserve a musicalwork across a difference in performance-means,as when Ferruccio Busoni reset for the piano cer-tain chorale preludes that Bach composed for thechurch organ. (We discuss this very example in thenext section.)

‘Musical transcription’ is an apt term for a dis-tinct and distinguished musical undertaking thathas engaged many composers and arrangers. Butthe label should not imply, of course, that nota-tional and ethnomusicological transcriptions havenothing musical about them. And it should not im-ply that all musical transcriptions go by this label.The musical undertaking we have in mind can goby other names—‘arrangement,’ ‘setting,’ ‘orches-tration,’ and ‘reduction’ being the most commonin English.4

Musical transcription is a highly circumscribedform of musical borrowing—a sort of limit case,in fact. J. Peter Burkholder usefully defines mu-sical borrowing as the taking of “something froman existing piece of music and using it in a newpiece.” And he adds that this “something may beanything, from a melody to a structural plan. Butit must be sufficiently individual to be identifiableas coming from this particular work, rather thanfrom a repertoire in general.”5 The musical tran-scriber can be regarded as a musical borrower whotreats a specific, preexisting work (or a clearly de-limited section of it, such as a movement) in itsentirety and unembedded in a longer work.6 Inorder to count as a transcription, this treatmentmust satisfy two additional constraints. First, thetranscriber aims, in ways we will explore, to pre-serve this work’s expressive content across somemusical difference, and not merely to use it as ma-terial in some new, derivative work. Second, shesucceeds in carrying out this preservation.7

Musical transcription has the conservative goalof reexpressing the content of the target work ina new musical context. And indeed, the phrase

Beaudoin and Moore Conceiving Musical Transdialection 107

‘reexpression’ suggests how musical transcriptionis, paradoxically, a sort of maximal form of mu-sical borrowing, and thereby nearly not a case atall. In musical transcription the original work isnot “borrowed” in the way one might borrow ahammer and some nails in order to build a shedor a theme in order to compose a set of variationsupon it. The musical transcriber aims not to createan entirely new (even if derivative) musical work,but rather, as it were, to redeploy or revoice theoriginal work in a new context.8

This explains some of our uneven descriptivetendencies. We do not know, for example, whetherto count a transcription as a new (even if max-imally derivative) work, and we do not knowwhether to count the transcriber as a cocomposerof the result. This seems to us to be largely a con-ventional matter of labeling: whether we give thetranscriber primary billing or list him more sec-ondarily as the “arranger” is largely a matter ofmarketing.

This conventionalism would follow from theview that the individuation of musical works issubject to indeterminacy.9 However, our treat-ment of musical transcription does not dependupon this or any other view about the contestedindividuation of musical works. We rely insteadupon a sufficiently robust notion of expressivecontent, which we will defend in Section IV. Same-ness of expressive content is clearly necessary forwork identity, but we are agnostic here aboutwhether it is also sufficient.

Musical transcription is not an automatic ormerely technical process. Transcriptions can behighly creative, as we will show in the next sec-tion, though the transcriber’s creativity is balancedagainst—or better, played out within—a guidingand constraining fidelity to the original work. Innegotiating this tension between authenticity andoriginality, the transcriber is, as Stephen Daviesnotes, like the performer: a good transcription,like a good performance, is faithful to the par-ent work while also providing the audience withsomething original. And like an interesting perfor-mance, what a good transcription often providesis some sort of insight into the parent work:

A transcription cannot help but comment on the originalin re-presenting the musical contents of the original, soa transcription invites reconsideration of and compari-

son with the original. Rather than being valued merelyfor making the musical contents of their models moreaccessible, transcriptions are also valued for enrichingour understanding and appreciation of the merits (anddemerits) of their models.10

Expanding on Davies’s observation, Paul Thomhas recently argued that, in this capacity, tran-scription can be viewed as a form of noncriticalinterpretation: while the music critic might saysomething about a work’s meaning or content,the transcriber (and also the performer and thecomposer of variations on a theme) can show it.11

This interpretative function has, we submit, be-come more prominent as the invention and widedistribution of musical recordings have increas-ingly obviated the transcriber’s traditional task ofsimply making a work more widely accessible, bytranscribing it for performance on the living roompiano, for example.12 (A similar shift occurred inpainting, where a rise in abstraction was concur-rent with the onset of photography.) This shift infunction helps explain the emergence, in the twen-tieth century, of a new, “transdialectical” form oftranscription.

ii. bach transcribed

We now discuss in some detail five twentieth-century transcriptions of works by Bach.13 Thesetranscriptions, which span the entire century(1907–1992), reflect what we regard as a generalemergence of musical “transdialection” from amore traditional trans-instrumental form of mu-sical transcription.

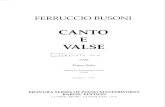

Bach–Busoni: In 1907, Feruccio Busoni soughtto transfer the original organ music of Bach’sKomm, Gott, Schopfer, heiliger Geist to the mod-ern piano.14 Busoni’s transcription nicely repre-sents a tradition of more or less “straight” pianotranscriptions that was already well establishedand widely practiced by the early twentieth cen-tury. But even in his relatively straightforwardtranscription, Busoni employs some artful con-structions of his own. In his score, Bach directsthe organist to perform organo pleno—that is, touse a substantial complement of pipes. Busoni, im-itating the octave-rich organ pleno sound, fills histranscription with numerous octaves that are not

108 The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism

present in Bach’s score, maximizing the timbre ofthe piano in an effort to emulate the sound of theorgan.

Bach’s original asks the organist to read threestaves of music at once: one for the left hand, onefor the right hand, and one for the pedals, operatedby the feet. It would have been an easy matter forBusoni to reduce the three staves of the organ mu-sic into a simplified version for piano written ontwo staves. However, Busoni, capturing the per-formative complexity of the original, ingeniouslymaintains a three-staved texture, with a stave forthe left hand, a stave for the right hand, and amiddle stave that uses both hands in alternation.

Busoni successfully preserves the overall toneof Bach’s chorale prelude, and indeed of the ex-alted plainchant on which it is based—“Come, Cre-ator, Spirit blessed!” Even though Busoni has notchanged the fundamental harmonic or melodiccontent of Bach’s original, he has neverthelesshad to make some slight musical changes in or-der to preserve across instruments the experienceof playing and hearing Bach’s work.

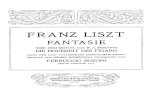

Bach–Webern: Anton Webern’s notorious 1934orchestral transcription of Bach’s six-part Ricer-car from The Musical Offering moves subtly awayfrom Busoni’s more traditional transcription.15

Webern’s conceptual leap is not to alter Bach’snotes or rhythms—they are all faithfully preserved.Rather, it is to break up Bach’s long contrapuntalmelodies into small units, distributing each melodyamong several different instruments. (The tech-nique is called Klangfarbenmelodie or tone-colormelody.) For example, a single instrument wouldoriginally play the first twenty notes of Bach’sfugue theme.16 But in Webern’s orchestral tran-scription, the first five notes are played by thetrombone, the next two by the horn, then two bythe trumpet, two by the horn with harp, dovetail-ing into four by the trombone, and so on.

Webern’s transcription is kaleidoscopic. Bach’soriginal lines are all present and accounted for,but each is “sung” by an unpredictable and ever-changing orchestral voice. Moreover, Webern’scoloristic choices foreground many short motivesthat are not heard as such in the continuity ofBach’s original. Since much of Webern’s own ma-ture music is made up of similar tiny motivic cells,his transcription is a “Webernization” of Bach.Nevertheless, while Webern’s fragmentation and

often lush twentieth-century colors seem poisedto break away into dodecaphonic variations, thosefamiliar with both works will hear the Webern asa faithful reexpression of Bach’s work, though itsextreme timbral discontinuities point the way to-ward transcriptions that are even looser musically.

Bach–Stravinsky: Igor Stravinsky’s 1955 tran-scription of Bach’s canonic variations on Von him-mel hoch da komm’ ich her marks an importantdeparture from the musically faithful transcrip-tions described above.17 Stravinsky reproduces allof Bach’s notes and rhythms, but then adds somethat are all his own. These additional notes areforeign not only to Bach’s original work but alsoto Bach’s musical language. In fact, they createchords that are quintessentially Stravinskian.

The clearest example occurs in Stravinsky’s set-ting of Bach’s Variation III. Early on, Stravinskyadds notes that echo Bach’s chorale melody, butat an interval (minor sevenths above and below)that creates a line foreign to Bach’s original. Theadded pitches form new harmonic collections (so-called 0257 collections such as C-D-F-G) that arecompletely absent from Bach’s compositional lan-guage. Music theorist Joseph Straus nicely summa-rizes the relationship:

Stravinsky’s added lines do not conform to the prevail-ing harmonic logic of Bach’s original. . . . The harmoniesformed by the lines are no longer triadic, but consistentlycreate a small number of non-triadic sets, particularlythe tetrachords 0247 and 0257, . . . which are principalmotives of [Stravinsky’s great neoclassical ballet] Pul-cinella as well. In this sense, the lines are regulated toeach other, but on Stravinsky’s terms, not Bach’s.18

Stravinsky intentionally here moves beyond thetranscriber’s traditional goal of remaining as faith-ful as possible to the musical notes and language ofthe original while adjusting to differences in per-formance means. He strives instead to preservethe work’s expressive content across a differencein musical language—a dialect he himself createdin his neoclassic period. But as we see it, Stravin-sky does not, in his work, build an entirely new mu-sical expression upon music he has borrowed fromBach. Rather, he provides a musical language—a palette of harmonic and timbral sensitivities—within which he endeavors to reexpress Bach’soriginal music. Stravinsky does not say something

Beaudoin and Moore Conceiving Musical Transdialection 109

new; he says in his own way what Bach previouslysaid in his, revealing features of the original in theprocess.

The passage we just discussed illuminates thepoint. The original chorale melody in Bach’s or-gan work is written as an inner voice, surroundedabove and below by other faster-moving linesof counterpoint. Stravinsky’s transcription fore-grounds Bach’s inner part in two ways: first, hescores the line for human voices, which alwaysbrings prominence; second, he uses brass instru-ments to echo the chorale melody in minor sev-enths. This is particularly elegant, since it is the“Stravinskian” additions that highlight and fore-ground an otherwise backgrounded element ofBach’s original counterpoint. For these reasons,we regard Stravinsky’s transcription as a solid ex-ample of what we call “transdialectical transcrip-tion” or, more simply, “transdialection.” The goalin this species of transcription is to revoice or re-express the original not (or not merely) across adifference in performance means, but across a dif-ference in musical dialect.

Bach–Friedman: Born in 1882, the same year asStravinsky, the Polish piano virtuoso Ignaz Fried-man likewise saw fit to add “non-Bachian” ele-ments to an original work by Bach. Friedman’s1948 arrangement for solo piano of the “Gavotte,en Rondeau” from Bach’s Partita No. 3 in E Majorfor Solo Violin modifies the original on two fronts:texture and harmony.19 Texturally, Friedman addsa thoroughgoing accompaniment to Bach’s origi-nal monophonic composition, which appears com-plete and intact as Friedman’s melody.20 Sincea melody–accompaniment texture is standard inFriedman’s late-romantic or early-modern style,his addition of accompaniment can be said to mod-ernize the texture of Bach’s original. Harmoni-cally, Friedman’s transcription begins by invokingBachian harmonies to support Bach’s line; how-ever, during a reprise of the rondeau theme (mea-sures 48–53), Friedman’s accompaniment veersinto a slippery, modern chromatic harmony thatis foreign to Bach’s language. During this passage,Friedman’s early twentieth-century harmonic sen-sibility exerts itself on Bach’s baroque melody.

Given Friedman’s additions, one might ques-tion whether Friedman’s treatment is really atranscription of Bach or whether it falls into abroader category of musical borrowing instead.

After all, composers (including classical variationwriters and modern jazz musicians) often bor-row a melody from a preexisting piece and re-harmonize it without the intention of reexpress-ing the work. In such cases, the earlier melodyis merely a compositional jumping-off point. ButFreidman’s treatment remains a transcription—more exactly, a transdialection—because it pre-serves the totality of Bach’s original. It does so byadding an accompaniment that is wholly in keep-ing with Friedman’s own musical style. For all ofhis pianistic modernizing, Friedman ingeniouslyreexpresses Bach’s original in an early twentieth-century voice.

Bach–Finnissy: We now turn to the examplethat opened our article, Michael Finnissy’s tran-scription of Bach’s “Deathbed Chorale,” so calledbecause Bach may have dictated the piece to acolleague during his final days of life.21 If Stravin-sky and Friedman crossed a conceptual thresholdhinted at by Webern, then Finnissy tramples thatthreshold and runs a good deal further for goodmeasure. For in Finnissy’s transcription the Bachoriginal is now increasingly difficult to perceive,both aurally and graphically.

Amidst the many alterations, Finnissy’s piecegenerally maintains a through line that followsBach’s counterpoint from beginning to end, but inalmost all cases the rhythms, pitches, and locationof the voices are distorted. To complicate mattersfurther, Finnissy adds some surrounding mate-rial, including other superimposed melodies fromBach’s original, and melodies from Alban Berg’s1935 Violin Concerto. Finnissy’s use of Bach’schorale prelude seems a direct challenge to thetraditional notion of transcription. But then whyshould we continue to regard Finnissy’s project astranscription?

It seems to us that, despite the significant mu-sical alterations, Finnissy’s fundamental aim is toremain faithful to Bach—to reexpress Bach’s orig-inal in Finnissy’s own twentieth-century musicallanguage. And this can be heard, though doing sorequires more than a casual listening (or a passingglance at the respective scores). We will brieflyhighlight three dimensions of transdialectical fi-delity—mood, texture, and relative historical com-plexity.

Though Bach’s score specifies no tempo mark-ing or performance indications, the piece is

110 The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism

profoundly melancholic: its contrapuntal unfold-ing is steadfast, lacking any obvious climax pointor shift in dynamics. The same can be said ofFinnissy’s transcription: his tempo marking readsLegatissimmo, sostenuto, intimamente (very con-nected, sustained, very intimate), while his dy-namic never rises above pianississimo (extremelyquiet). Though Finnissy shifts the position ofBach’s lines and confounds their tonal logic, theynevertheless maintain a mood of calm, contrapun-tal rumination.

The Bach and the Finnissy also share musi-cal texture. Each exhibits a pattern of four-voicecounterpoint that winnows to a single voice, thenworks its way back to four voices, only to oscillateback again. In both, the simultaneous deploymentof various lines inhibits the dominance of any sin-gle melody.

Finally, Finnissy’s transcription inhabits a simi-lar position with regard to his own contemporarymusical environment as Bach’s did to his. Bach’s“Deathbed Chorale” is a work of extreme con-trapuntal complexity: written in 1750, this four-part chorale prelude stood at the pinnacle of alearned practice that had already gone out offashion. It features contrapuntal techniques suchas vorimitation (a foreshadowing of the choralemelody), augmentation (the reappearance of cer-tain lines in doubled note values), and inversion(whereby a line of counterpoint is answered byan upside-down version of itself). But these tech-niques were outmoded at the time of composi-tion, having been supplanted by a less contra-puntally complex Galant style, exemplified bycomposers such as Bach’s son, Johann ChristianBach (1735–1782), in which a well-defined melodywith a supportive, nonimitative bass was the norm.

The contrapuntal fabric of Finnissy’s work—with each hand playing multiple voices and vir-tually no sense of prevailing meter—strikes oneas cryptic, in just the way that Bach’s four-partchorale prelude might have struck his own Galantcontemporaries. Only a handful of composerscurrently write music with Finnissy’s level ofrhythmic complexity. And the profoundly atonalharmonies and dissipating, noncadential phrasesdiverge from the prevailing pop, minimalism, andmore overtly “tuneful” musical landscape of mod-ern Britain, where Finnissy lives and works. Thework’s opening chord (B, C, E-flat, F-sharp, G)

has no place within common tonal practice, andincludes a level of dissonance not often foundoutside of high-modernist or avant-garde circlesin the late twentieth century.

Finnissy accomplishes these significant musi-cal similarities despite the striking musical differ-ences we noted at the outset. But did Finnissyintend to carry out what we hear as an expres-sive transdialectical preservation? Concerning thepiece at hand, Finnissy writes: “Layered frag-ments of Bach’s chorale-prelude (BWV 668) sur-face throughout, but no consistent ‘tonality’ is sug-gested as a context. The constituent measures ofthe original are constantly melting away, refractedthrough varying intervals of transposition, under-mining any sense of rational ‘perspective.’”22

Finnissy’s expressed goal of undermining tonal-ity and “rational perspective” might seem to con-flict with the preservational aspirations of thetranscriber. But consider how Finnissy describesanother of his transcriptions—this time of Verdi:23

“I worked from an earlier transcription byAlexander Abercrombie, generally increasing theharmonic ambiguity, eliding the original phrases,re-voicing Verdi’s (orchestral) texture, creating akind of production of the scene in my imagina-tion.”24

Here the move away from a determinate “per-spective”—or at least toward greater harmonicambiguity—is presented less as an attempt toundermine the original and more as a way ofimaginatively restaging the original in Finnissy’sown musical language. The point to recognizeis that Finnissy’s general musical style traffics inthe overlaying, the clashing, and the ultimate de-struction of fixed perspective—an expressive voicenot entirely foreign to contemporary artists. So,the “perspective-denying” features of the musicproperly characterize not some nontranscriptivegoal, but rather the character of the musical lan-guage within which Finnissy endeavors to reex-press Bach’s work.

Finnissy’s bold treatment of Bach is so success-ful precisely because of the insight it gives intoBach’s original. The numerous stepwise motivesin Finnissy’s transcription recapitulate Bach’s con-trapuntal voices, but Finnissy’s freely atonal lan-guage allows us to hear them anew, accentuatingthe poignancy of the title, “When we are in thedeepest need.” Despite—or, as we have claimed,

Beaudoin and Moore Conceiving Musical Transdialection 111

because—of Finnissy’s acknowledged attempt to“frustrate and deny the logic” of Bach’s original,Wenn wir in hochsten Nothen sind seems to us to bea more developed instance of the new form of thetranscription glimpsed in Webern and ventured byStravinsky and Friedman.

iii. transdialection translated

If we are right, a new musical undertaking—transdialection—has begun to emerge from a moretraditional, trans-instrumental form of musicaltranscription. There are several reasons this mayhave happened when it did. One is the twenti-eth century’s increasingly intensified thirst for newartistic forms. But there is also the shift in func-tion mentioned in Section I: since we can nowhear a recording of the original with a click ofthe mouse, the need simply to access the work nolonger creates much of a demand for traditional,trans-instrumental transcription.25 This would un-derstandably lead transcribers to experiment withdifferent transformations as a way of carrying outthe now heightened function of providing new in-terpretative perspectives. But the functional shiftalso foregrounds a different type of accessibil-ity: transdialection can serve to make the origi-nal work accessible to an audience whose musi-cal dialect has different expressive sensitivities.26

Although we may have recordings available tous and although our powers of musical discrim-ination may be just as refined as any citizen ofeighteenth-century Leipzig, the expressive con-tent of Bach’s works may nevertheless be difficultfor us to access because of a dialectical differencein the way musical features map onto expressiveones.

To appreciate this point, consider an anal-ogy with poetic translation—an analogy the word‘transdialection’ wears on its sleeve. Our capacityto understand music that is very foreign to us willbe limited until we spend time accommodating tothe culturally different musical fabric in which it iscreated and expressed. However, we can access atleast some central expressive features of most mu-sic that hits our ears. Certainly those surroundedby Western popular music can listen to Bach witha modicum of musical understanding. So, in mostcases, the musical transformation we have high-

lighted is usefully thought of as crossing musicaldialects, not languages (though the distinction is,of course, metaphorical and vague). It is for thisreason that we have appropriated a term that hasbeen used to refer to the intralinguistic translationof literature.

In fact, the term ‘transdialection’ is as rare asthe practice it names.27 And for good reason: weusually think it sufficiently easy and valuable tolearn enough of a different dialect so that we canread an original work as is. Indeed, we often learna dialect in the very process of trying to inter-pret a text written within it. But this norm is notalways in place: it might be important to makethe original accessible to those who cannot or willnot cross a dialectical divide, and we might alsothink that doing so sheds illuminating light on theoriginal. And so there are modern-English trans-dialections of, for example, the King James Bible,Shakespeare, and even David Hume.28

But musical transdialection also trades in strictfidelity to notes and rhythms for reexpression ofa deeper sort. And although intralinguistic trans-lation of any type is rare, certain interlinguistictranslations have certainly had the analogous goalof reexpressing a piece of literature not merely inthe words of a different language but in the mind-set of a different age. Among the many trade-offsa translator needs to weigh is one of purpose: isthe translation to serve simply to make the orig-inal accessible to someone who cannot speak theoriginal language or might it also serve to reex-press the original along some other dimension? Alooser translation which sheds light on the originalby bringing to the fore one of its hidden aspects orby reexpressing it against contemporary sensibili-ties is more to the point when the target audienceknows at least some of the original language.

As Peter Green notes in the preface to his re-cent translations of Catullus, “from the Renais-sance to comparatively recent times, literary (asopposed to informational) translations have al-most always had as their target other scholars andmen of letters who knew the original language, andwho would thus appreciate elegant pastiche.”29 Toarticulate the typical aim for such “literary transla-tions,” Green cites John Dryden, who “justified hisextensive Anglicization of whatever ancient poethe tackled on the grounds that ‘my own [version]is of a piece with his, and that if he were living, and

112 The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism

an Englishman, they are such as he would prob-ably have written.’ ”30 Exactly the same concep-tion, articulated in much the same counterfactual,guided Robert Lowell when, three centuries afterDryden, he undertook a book of translations hecalled Imitations:

Boris Pasternak has said that the usual reliable trans-lator gets the literal meaning but misses the tone, andthat in poetry tone is of course everything. I have beenreckless with literal meaning, and labored hard to getthe tone. Most often this has been a tone, for the tone issomething that will always more or less escape transfer-ence to another language and cultural moment. I havetried to write alive English and to do what my authorsmight have done if they were writing their poems nowand in America.31

Of course, Dryden and Lowell articulate just oneconception that might guide a project of poetictranslation. We might debate the utility of such“imitations” on a given occasion: for a bilingualaudience, it is only “literary” translations of thistype that will be of any value, while other audi-ences may call for a stricter, more “informational”translation. In any case, we find it useful to regardmusical transdialection as an intralinguistic andmusical analogue to the interlinguistic projects ofliterary translation in which Dryden, Lowell, andothers have engaged.

iv. transdialection defended

We now sharpen the notion of transdialection byresponding to a pair of objections—one about itsintelligibility and a second about its applicabil-ity. The first worry is conceptual: the notion oftransdialection assumes that there is somethingthat can be recomposed or reexpressed. But whatis this “thing”? It is not, of course, the exact se-quence of notes and timbres that are preserved,since it is precisely these that the transcriber al-ters. The same holds for the notations in the origi-nal score. We have avoided any assumptions aboutwork identity and have talked instead about thepreservation of a work’s “expressive content.” Butwhat is this exactly? And how is it determined? Ifmusic were fully like a natural language, then wemight appeal to some sort of denotational seman-

tics for help. But our metaphorical talk of musicallanguages and dialects is meant only to highlightthe culturally contingent and conventional quasi-syntactic constraints of genre and musical culturethat allow a piece of music to achieve its expressiveeffects.

This first, and most important thing to noteis that this worry applies to any notion of tran-scription, including the more traditional trans-instrumental variety. Not only do most theoreti-cal treatments of traditional transcription speakexplicitly about expressive content and its cog-nates, but the traditional transcriber is also clearlyguided in his choices by a sense of something morestable and, dare we say, deeper than the sheernotes of the original. So, the first objection un-dermines our notion of transdialection only inso-far as it undermines the intelligibility of the well-established practice of transcription generally.

Still, it would be nice to say more. Alas, we donot have a theory of expressive content to offer.But in fact, we do not think we need one for ourpurposes. We are sympathetic to the possibilitythat this term (and this notion) shifts its semanticfocus along with the diverse aims and standardsof our musical practice and discourse. And so, thenotion of expressive content may not get at any-thing entirely fixed.32 If this is right, then talk ofa work’s content arises from (and is sustained by)a sort of semantic pretense that composers, per-formers, listeners, and music writers implicitly andcollectively engage in. (Perhaps it is like our reify-ing talk of “the average American couple” with 1.7children. And live where—Springfield?) When se-mantic push comes to metaphysical shove, it maybe that this talk is subtly misleading: it purports toget determinately at something fixed and precise,while it is actually activated in a more rough andready way by shifting clusters of a work’s aesthet-ically relevant properties.

If this is right, then “expressive content” mightoccasionally be vague in application, and thisvagueness would ramify, affecting concepts suchas that of a musical transcription that are builtupon it. In the case of musical transdialection,the presumption is that the successful transcriberhas pursued a determinate musical isomorphism—a function that takes a musical feature in the di-alect of the original and yields a musical featurein the new dialect that gives rise there to the same

Beaudoin and Moore Conceiving Musical Transdialection 113

expressive feature.33 In practice, of course, theexact mapping, not to mention the individuationof musical features, of expressive features, and,indeed, of musical dialects, is shot through withindeterminacy and vagueness. And this explains,among other things, the difficulties we sometimeshave in determining whether certain borderlinemusical undertakings count as transdialections oras some sort of looser form of musical borrowingon the way to musical pastiche or homage.34

But even if the notion of expressive contentis looser and more unsettled than it seems, it issufficiently constrained, even if we cannot explic-itly say quite how, to play a useful role in ourthought and talk about music. Frequently enough,we make clear, justified, and even legal judgmentsabout which musical undertakings are transcrip-tions and which are not. This practice not onlypins down a robust notion of transcription, butit also helps determine the correlative notion ofexpressive content that is bound up with it.

The second worry is empirical: even if transdi-alection is intelligible in principle, is it clear thatStravinsky, Friedman, Finnissy, or anyone else hasreally engaged in it? We suggested in Section Ithat musical transcription of any stripe is both anintentional and a normative notion. In saying thatmusical transcription is intentional, we mean thatthe transcriber paradigmatically intends to pre-serve a work’s expressive content across some dif-ference in musical context.35 This intentional con-dition is not sufficient, however, since a would-betranscriber might fail to pull it off. So transcrip-tion is also a “success notion”—the musical detailsmatter. Whether or not the constructions of We-bern, Stravinsky, Friedman, and Finnissy count astransdialections depends, then, upon whether theysatisfy these two conditions in turn.

So did our transcribers really intend theirconstructions as transdialections? Here self-descriptions, like the ones we have quoted,are relevant. And we think the evidence sup-ports an intention to transdialect.36 It is alwayspossible, though, for an artist to “play off” agenre. Finnissy’s self-descriptions, for example,are highly nuanced, and it is possible that hisproject merely starts with transdialection andbuilds upon, or perhaps against it.

It is also possible for an artist, like anyone else,to hide his real intentions from the public, or even

from himself. Joseph Straus has argued that thevery recompositions of Stravinsky and Webernthat we have discussed were not “undertaken inthe spirit of homage, the generous recognition byone master of the greatness of an earlier master.The internal evidence of the pieces, on the con-trary, suggests a vigorous and self-aggrandizingstruggle on the part of the later composer to asserthis priority over his predecessor, to prove himselfthe stronger.”37 If Straus is right, his claim wouldhold despite any public or even private proclama-tions these composers might have made.

What then of our second condition: intentionsaside, did our transcribers succeed in transdialect-ing Bach? This question embroils us, of course, inthe vagaries of expressive content that we touchedon above: just which musical details are relevantmight be indeterminate and shift with explanatorycontext. But as we have emphasized, this complex-ity is not all-encompassing, since we are capableof judging determinate success and failure in agreat many cases. And we have given solid musicalevidence that Webern, Stravinsky, Friedman, andFinnissy succeeded in transdialecting Bach. Still,clinching the case would involve a much more ex-tended musical discussion.

In any case, we take ourselves to have openedup a new hermeneutic possibility: with transdialec-tion as a theoretical possibility, musical details thatmight otherwise point, for example, to what Strausregards as content-destroying one-upmanship onthe part of certain twentieth-century composerscan be understood instead as manifesting variousprojects of transdialection.38 We submit that, forboth music theorists and philosophers trying tounderstand our transcriptive practice, the notionof transdialection is squarely in play.

v. transdialection extended

Our focus here has been on the practice of musi-cal transcription as it has been carried out withinWestern classical music. Our main claim has beenthat this practice is best understood as extending,over the last century, into an undertaking we havearticulated and defended as transdialection. This,we think, is already a significant reconception ofan important practice. But it also seems to us thatthe notion of transdialection has intriguing and

114 The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism

illuminating conceptual connections with certainother artistic practices. We end by briefly men-tioning some of these.

One connection is with the practice of produc-ing covers in rock, jazz, and other popular idioms.To elaborate with just one example, Joe Cocker’sfamous cover of the Beatles’ With a Little Helpfrom My Friends seems simultaneously to be botha performance of the Beatles’ song and also a dis-tinctive version of it. (Musicians might deliber-ate about whose version to perform.) In the lat-ter capacity, Cocker’s cover seems to us to be atransdialection of the Beatles’ original: it is a re-expression of the original in Cocker’s distinctivelyexpressive musical dialect, and it provides an in-teresting and informative “noncritical” interpre-tation of the original.

Transdialection might also be useful in under-standing the development of certain oral and folktraditions. Examples include the development ofearly American blues music, wherein regionalstyles and instrumental preferences forced incom-ing songs into new arrangements, and the “‘dop-tion” tradition of the Trinidadian Spiritual Bap-tists, wherein Southern Baptist hymns becamewordless devotional pieces. In both cases, preex-isting, though typically unscored, pieces of musicseem to be intentionally reexpressed in modifiedmusical contexts, in the manner of transdialection.

Transdialection may also have illuminating con-nections with artistic practices outside of music.We have already explored the analogy with liter-ary translation. But might we also view certain lit-erary and cinematic adaptations as undertakingsin the mold of transdialection? To take the case offilm, Brian De Palma’s 1983 “remake” of the 1932Scarface might count as a transdialection because,although it alters details of setting, character, andeven plot, it seems to do so in order to preserveand re-present the original’s expressive content inan historically updated context.

These possible extensions will have to negoti-ate vague borderlines analogous to that between

musical transdialection and looser forms of musi-cal borrowing. But as in the case of transdialection,doing so will be illuminating. Why is it, exactly, thatDr. John seems clearly to have transdialected theworks of Johnny Mercer on his recent album, Mer-cernary, while John Coltrane seems, in his famousrecording, to use Rogers and Hammerstein’s “MyFavorite Things” merely as a jumping-off point fora quite different musical expression? Does JaneSmiley’s treatment of King Lear in her ThousandAcres (1991) count as transdialection or rather as alooser form of literary adaptation—a “deconstruc-tion,” perhaps? Did Joyce transdialect Homer’sOdyssey? Asking such questions with the gener-alized notion of “reexpression” might illuminatethese and many other works.

Finally, we do not mean our investigation tobe merely descriptive: we hope that, once transdi-alection is explicitly seen as a distinct and entirelylegitimate musical undertaking, it will be evenmore widely practiced. For transdialection seemsa fruitful way of engaging music across wide differ-ences in musical context—a way not only of mak-ing more readily and differently accessible worksthat are expressed in distant musical dialects butalso of shedding new interpretative light uponthem.39

RICHARD BEAUDOINDepartment of MusicHarvard UniversityCambridge, Massachusetts 02138

internet: [email protected]

JOSEPH MOOREDepartment of PhilosophyAmherst CollegeAmherst, Massachusetts 01002

internet: [email protected]

Beaudoin and Moore Conceiving Musical Transdialection 115

116 The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism

1. The first figure is the first four measures of JohannSebastian Bach’s Chorale Wenn wir in hochsten Nothen sein,BWV 668a, composed in 1750. The second is the first systemof Michael Finnissy’s Wenn wir in hochsten Nothen sind,Work No. 177, composed in 1992, published in Finnissy:Collected Shorter Piano Pieces Vol. 2 (Oxford UniversityPress, 1998), and reproduced by permission.

2. Julian Silverman, “Aspects of Complexity in RecentBritish Music,” Tempo New Ser. 197 (1996): 33–37, at p. 37.

3. For more on ethnomusicological transcription, see TerEllingson, “Transcription (i),” entry in Grove Music Online(Oxford University Press, 2007), whence we derived the la-bel. For more on transcription in the jazz tradition, see MarkTucker and Barry Kernfeld, “Transcription (ii),” entry inGrove Music Online (Oxford University Press, 2007).

4. We also do not mean to imply that our taxonomy is ex-haustive. In fact, there is at least one further use of the word‘transcription’—we might call it “medial transcription”—inwhich we pick out the process of transferring music from onenon-instrumental and relatively proximal source (such as astorage medium) to another, as in a “broadcast transcrip-tion” or a dubbing. For more on this notion of transcription,see Howard Rye, “Transcription (iv),” entry in Grove MusicOnline (Oxford University Press, 2007).

5. J. Peter Burkholder gives this definition on p. 863of “The Uses of Existing Music: Musical Borrowing as aField,” Notes, Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Asso-ciation, 2nd Ser. 50 (1994): 851–870. He goes on to providea tentative typology of musical borrowing and urges furtherstudy of the field. We regard our article as one response toBurkholder’s invitation.

6. Requiring in our definition that the transcribed workpreexists ensures that later drafts in a compositional pro-cess do not count as transcriptions of previous ones. We getthis point from pp. 216–217 of Stephen Davies, “Transcrip-tion, Authenticity, and Performance,” The British Journalof Aesthetics 28 (1988): 216–227. Requiring the treatmentof entire works, or clearly delimited sections thereof, marksoff transcription from certain other forms of musical bor-rowing, such as theme and variation. And requiring thatthe transcribed material be unembedded rules out a sort ofextended musical quotation in which a work is sandwichedbetween bits of new music, thereby transforming the overallexpressive content of the original.

7. We will say more about these two conditions laterin the article. We note here, though, that our commitmentto the first, “intentional” condition is qualified: certainly,it is satisfied in all cases of actual transcription, but ourreceived concept of transcription does not seem sufficientlydeterminate to rule out the possibility of an unintendedtranscription.

8. That there is a tenable and useful, even if intentionaland vague, distinction between the revoicing or reexpres-sion of a work and a mere appropriation of it is a centralimplication of our article. For an example clearly on the farside of the distinction, consider Perotin’s Alleluia: Nativitas,written around 1200. In this organum, Perotin greatly elon-gates a preexisting Gregorian chant and uses it as a cantusfirmus, over which he composes two new, fast-moving lines.The original music is obscured—at times, over sixty notessound over a single note of the borrowed chant. Since thepreexisting music is used as a kind of hidden scansion onwhich the new music rests, Perotin has here appropriated a

monophonic chant, and incorporated it as part of his newpolyphonic work.

9. This view is defended in Joseph Moore, “MusicalWorks: A Metaphysical Mash-up,” unpublished manuscript.

10. Davies, “Transcription, Authenticity, and Perfor-mance,” p. 221.

11. Paul Thom, The Musician as Interpreter (Pennsylva-nia State University Press, 2007).

12. Along with making a work more accessible and pro-viding an interpretation of it, Davies notes that transcrip-tions have also played a role in musical pedagogy and inproviding a vehicle for a composer to show off his compo-sitional skill. Since it seems to us that this last function isachieved by carrying out one of the others, and since ped-agogy is not at play in the transcriptions we will discuss, itis only the first two functions—increasing accessibility andproviding interpretation—that will be at play in our discus-sion.

13. We do not have space to discuss these transcrip-tions in more detail, much less to discuss additional ex-amples. Please contact the authors for access to recordingsof the examples we discuss. See our appendix for a spec-trum of selected Bach borrowings. And for a more exten-sive (though still partial!) list of transcriptions and othersettings dedicated to works of Bach alone, see www.bach-cantatas.com/NVD/PT.htm.

14. Bach Original: Komm, Gott, Schopfer, heiliger Geist,BWV 667, ca. 1708–1709; Busoni Transcription: Komm,Gott, Schopfer, heiliger Geist from 10 Chorale Preludes, orig-inal organ works by J. S. Bach, “Transcribed for the piano inchamber style” by Ferruccio Busoni, 1907–1909.

15. Bach Original: Fugue (Ricercare) a 6 from DasMusikalische Opfer, BWV 1079, 1747. Webern Tran-scription: Fugue (Ricercare) a 6 from Das MusikalischeOpfer, arranged for orchestra by Anton Webern in 1934–1935.

16. The six-part Ricercare is somewhat unique in Bach’soeuvre, since he wrote it in “open score,” meaning that noexact instruments were specified.

17. Bach Original: Einige canonische Veranderungenuber das Weihnachtslied: “Von himmel hoch da komm’ ichher” vor die Orgel mit 2 Clavieren und dem Pedal, BWV769, 1746–1747. Stravinsky Transcription: J. S. Bach: Choral-Variationen uber das Weihnachtslied Von Himmel hoch dakomm’ ich her Gesetzt von (“set by”) Igor Stravinsky formixed chorus and ensemble in 1955–1956.

18. Josef Straus, “Recompositions by Schoenberg,Stravinsky, and Webern,” The Musical Quarterly 72 (1986):301–328, at pp. 320–323.

19. Bach Original: “Gavotte, en Rondeau” from the Par-tita No. 3 in E Major from Sei Solo a violino senza Bassoaccompagnato, BWV 1006, 1720. Friedman Transcription:“Gavotte, en Rondeau” from the Partita No. 3 in E Major,arranged for solo piano by Ignaz Friedman, published 1948.

20. Occasionally, Friedman adds countermelodies abovethe source material, but Bach’s original is never challengedas the hauptstimme, or most prominent voice, of the texture.

21. Bach Original: Wenn wir in hochsten Nothen sein, byJ. S. Bach, BWV 668a, 1750. Finnissy Transcription: Wennwir in hochsten Nothen sind, by Michael Finnissy, “based onthe Chorale-Prelude by J. S. Bach BWV 668,” written forpiano in 1992. For a summary of the complex heritage ofthe “deathbed” attribution, see David Yearsley, Bach and

Beaudoin and Moore Conceiving Musical Transdialection 117

the Meanings of Counterpoint (Cambridge University Press,2002).

22. Michael Finnissy, liner notes from “Michael Finnissy:Etched Bright with Sunlight,” Nicholas Hodges, piano(Cornwall, UK: Metronome Recordings, compact disc MET1058, 2002): 2–5, p. 3.

23. Verdi Transcription No. 10 (“Me pellegrina ed or-fana,” 1986–1988).

24. Finnissy, “Michael Finnissy: Etched Bright with Sun-light,” p. 3.

25. Traditional transcriptions are still useful, of course,for pedagogical reasons—for example, simplified versionsfor student performers and as exercises for aspiring com-posers, including would-be transdialectors.

26. For an example of the way musical transcription canbe used to make Bach accessible to a contemporary audi-ence, consider the recordings of Bela Fleck and the Fleck-tones—for example, Bach Fugue No. 2, from The HiddenLand.

27. It is so rare in fact that we thought we had coined it,until we looked it up. The Oxford English Dictionary showsthe term used as early as 1698, and, interestingly, in 1776 bythe English music historian, Charles Burney.

28. See, respectively, lfnexus.com/weareforanewtransdialectionofthekingjamesversionofthebible.htm,www.csulb.edu/"richmond/Shakespeare.html, and http://www.earlymoderntexts.com/f_hume.html.

29. Peter Green, The Poems of Catullus: A Bilingual Edi-tion (University of California Press, 2005), p. 25.

30. Green, The Poems of Catullus, p. 25.31. Robert Lowell, preface to Imitations (1961),

reprinted in Collected Poems, ed. Frank Bidart and DavidGewanter (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003),p. 195.

32. Compare Paul Thom: “I believe that there is no ab-solute criterion on the basis of which we can give a uniformdetermination of what should be included in a work’s con-tent. The transcriber’s decision about what to count as thework’s content will be relative to his or her purpose.” TheMusician as Interpreter, p. 11.

33. Since there may be several musical features in thenew dialect that exhibit the relevant expressive feature,there may be several mapping functions that ground a givenproject of transcription. (We could say, alternatively, thatthe relevant mapping relation is not always a function.) Itis important to emphasize, though, that the relevant func-tions (and associated transcriptive projects) are relativizedto musical dialects, and this puts significant constraints on aproject’s success conditions. There is, to be sure, some map-ping function—and so, some conceivable project of transdi-alection—according to which Stravinsky’s Pulcinella countsas a transcription of Bach’s The Musical Offering. But rel-ative to the respective musical dialects of Stravinsky andBach, Pulcinella clearly and determinately fails to transdi-

alect The Musical Offering. We thank Diana Raffman forpushing us on this point.

34. A transdialection can, of course, shed light on theoriginal by selectively highlighting certain of the original’sexpressive features while downplaying others. But a musi-cal undertaking can count as a transdialection even whenthe reexpression engages in a somewhat broader conversa-tion with the original. How broad can this “conversation”be? This is clearly a vague matter, though transdialectiondoes not extend to undertakings whose expressive feel isprimarily one of interrogation, much less of subversion ornew construction. There is obviously much more to be saidhere, and we hope to say some of it in a future project. (Wethank an anonymous referee for highlighting this issue.) Inthe meantime, see the appendix for our view of where someother examples fall on the spectrum.

35. As we noted in Section I, there is surely enough in-determinacy in the notion of a transcription that one mightlabel as a “transcription” some far-fetched composition thatwas not intended as such. Despite this, the intentional condi-tion seems central to the notion, though dropping it would,of course, only strengthen our empirical claims.

36. We do not require, of course, that a transdialectorconceive her project with the explicit understanding we havearticulated here, much less that she use our label.

37. Josef Straus, “Recompositions by Schoenberg,Stravinsky, and Webern,” p. 327.

38. As another example where our notion might beuseful, consider Stephen Davies’s wavering description ofStravinsky’s Pulcinella: “Stravinsky does more than re-orchestrate Pergolesi’s music, he adds to it. But he doesso with a light touch, aiming to add an ‘edge’ to the soundrather than to recompose Pergolesi’s piece. So, though Pul-cinella has a Stravinsky-like sound one would not asso-ciate with Pergolesi, the work is more like a transcriptionthan anything else. It is a work by Pergolesi/Stravinsky, notby Stravinsky alone” (Davies, “Transcription, Authenticity,and Performance,” p. 219). What Davies seems to wantto say—what he could say with our terminology—is thatPulcinella is determinately a transdialection of Pergolesi’spiece. And we agree that certain movements of Pulcinellamight, indeed, be classified as transdialections. However,we have not discussed Stravinsky’s Pergolesi-inspired bal-let because it does not treat a single work by Pergolesiand because many of Stravinsky’s source movements werenot written by Pergolesi, though Stravinsky thought theywere.

39. An earlier version of this article was delivered at theASA Annual Meetings in November 2008. We thank theaudience members on that occasion and particularly ourcommentator, Diana Raffman. For additional comments,suggestions, and helpful examples we thank James Harold,Greg Hayes, Tom Wartenberg, and an anonymous refereefrom this journal.