Communist Nostalgia and the Consolidation of Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe

-

Upload

valentina-oprea -

Category

Documents

-

view

53 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Communist Nostalgia and the Consolidation of Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe

This article was downloaded by: [Central U Library of Bucharest]On: 31 May 2013, At: 05:43Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number:1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street,London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Communist Studiesand Transition PoliticsPublication details, including instructions forauthors and subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjcs20

Communist nostalgia and theconsolidation of democracy inCentral and Eastern EuropeJoakim Ekman a & Jonas Linde ba Department of Social and Political Sciences,Örebro University, Swedenb Örebro University, SwedenPublished online: 12 Apr 2011.

To cite this article: Joakim Ekman & Jonas Linde (2005): Communist nostalgiaand the consolidation of democracy in Central and Eastern Europe, Journal ofCommunist Studies and Transition Politics, 21:3, 354-374

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13523270500183512

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private studypurposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution,reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make anyrepresentation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up todate. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should

be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall notbe liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs ordamages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly inconnection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

Communist Nostalgia and theConsolidation of Democracy in Central

and Eastern Europe

JOAKIM EKMAN and JONAS LINDE

In recent years, public opinion surveys have testified to increasing levels of ‘communistnostalgia’ in Central and Eastern Europe: that is, growing numbers of citizens who feelthat ‘a return to communist rule’ would in fact be a preferable option. These apparentlynon-democratic sentiments have been subject to two alternative explanations – onerelated to political socialization and the other to system output. In fact, communist nos-talgia is a multidimensional phenomenon, encompassing both generational differencesand general discontent. However, it is clear that nostalgia is more closely related to dis-satisfaction with the present system’s ability to produce output than to genuine non-democratic values.

Introduction

This article deals with a phenomenon which has received very little attention

in the vast body of research on democratic consolidation in post-communist

Europe, namely ‘communist nostalgia’. In recent years, public opinion

surveys have alerted us to an emergent retrospective positive evaluation of

the old regime among the citizens in Central and Eastern Europe; in other

words, growing numbers of respondents feel that ‘a return to communist

rule’ would in fact be a desirable option. Does this kind of nostalgia constitute

a threat to democratic consolidation? Drawing on the New Europe Barometer

and other cross-national public opinion surveys, this study sets out to examine

Joakim Ekman is a doctor of political science and a research fellow at the Department of Socialand Political Sciences, Orebro University, Sweden. His publications include The Handbook ofPolitical Change in Eastern Europe, 2nd edn, co-written and co-edited with Sten Berglund andFrank H. Aarebrot (2004). He is currently completing a book about public opinion in the EU.Jonas Linde holds a Ph.D. in political science from Orebro University, Sweden. He has publishedin European Journal of Political Research, Problems of Post-Communism and Perspectives: TheCentral European Review of International Affairs. His current research interests are in the fields ofcomparative politics, European politics and democratic consolidation.

Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, Vol.21, No.3, September 2005, pp.354–374ISSN 1352-3279 print=1743-9116 onlineDOI: 10.1080=13523270500183512 # 2005 Taylor & Francis

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

the determinants of ‘communist nostalgia’ and its implications for democratic

consolidation in Central and Eastern Europe. Two alternative explanations for

the emergence of nostalgia are put to the test: one hypothesis related to politi-

cal socialization and the other related to system output. The analysis thus con-

cerns two aspects of public opinion in new democracies: popular support for

the current democratic regime and public evaluations of the former non-

democratic regime.

A Mass-Level Perspective

Throughout the 1980s, a preoccupation with formal institutions and political

elites could be observed in studies of democratic transition and consolidation.

Much of the research focused on institutional and constitutional configurations

conducive to successful democratization and consolidation of democracy. In

the 1990s, however, following the demise of communism in Central and

Eastern Europe, we have witnessed something of a renaissance of political

culture in democratization studies. Even though institutional engineering

and the strategies of political elites are important aspects of the uncertain tran-

sition phase, the process of democratic consolidation also requires system

support on the mass public level. Simply skilful institutional engineering

and elite-level manoeuvring cannot alone produce sustainable democracy.1

Consequently, recent works on democratic consolidation have also empha-

sized the importance of public opinion in new democracies.2 In this article,

such a mass-level perspective will be employed.

Since 1 May 2004, eight of the countries analysed here have been

members of the European Union, and the remaining two (Bulgaria and

Romania) are expected to gain full membership in 2007. Furthermore, in

March 1999 the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland joined the North Atlan-

tic Treaty (NATO), and at a meeting in Prague on 12 December 2002, the

remaining seven countries in our sample were formally invited to join that alli-

ance as well. Recent studies have demonstrated widespread public support for

democracy in most of the countries in contemporary Central and Eastern

Europe, and thus it might seem uncalled for to worry about democratic break-

down in this part of the world.3 However, ‘democratic consolidation’ is not

only about avoiding breakdown or ensuring democratic regime survival.

True, this ‘negative’ perspective on democratic consolidation has been the

most common in the literature on post-communist Europe.4 In this study,

however, we adopt a ‘positive’ approach towards democratic consolidation,

focusing on the development or improvement of already existing democracies.

From this perspective, ‘communist nostalgia’ obviously needs to be con-

sidered when taking stock of the attitudinal consolidation of democracy in

post-communist Europe.

COMMUNIST NOSTALGIA IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE 355

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

Conceptualizing Communist Nostalgia

‘Nostalgia’ is a multidimensional concept, and its usage is dependent upon

context as well as level of abstraction. According to Webster’s Third New

International Dictionary of the English Language, nostalgia could be either

‘a severe melancholia caused by protracted absence from home or native

place’ or ‘a wistful or excessively sentimental sometimes abnormal yearning

for return to or return of some real or romanticized period or irrecoverable

condition or setting in the past’.5 Both of these definitions underline the funda-

mental emotional basis of nostalgia. In the poetic words of H.W. Longfellow

(1807–82), nostalgia is ‘a feeling of sadness and longing that is not akin to

pain, and resembles sorrow only as the mist resembles the rain’.

In everyday language, however, the concept seems to indicate more than a

mere sentimental longing for the good old days. Also, it arguably carries con-

notations of something not quite genuine, a selective image of the past, some-

times cast in a conservative or even reactionary form. When analysing

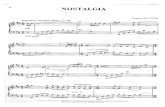

‘communist nostalgia’ in this article, we distinguish between four analytical

dimensions of the concept: one political–ideological dimension, two socio-

economic dimensions, and one life biography dimension (see Figure 1).

Focusing mainly on the political–ideological and the socio-economic dimen-

sions, we examine different possible explanations for the existence of

FIGURE 1

DIMENSIONS AND INDICATORS OF COMMUNIST NOSTALGIA

356 JOURNAL OF COMMUNIST STUDIES AND TRANSITION POLITICS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

nostalgia. The two basic questions could be formulated thus: is the presence of

communist nostalgia an indication of genuine non-democratic values among

the post-communist citizens, acquired as the result of political socialization

in the old, communist system? Or, is the presence of nostalgia quite simply

brought about by a perceived output deficit, and related to a general discontent

with the democratic system’s performance ability? We shall return to this

discussion below.

The personal dimension of nostalgia has to do both with (selective) mem-

ories of the past and a retrospective revaluation of life under communism, as

well as evaluations of the personal post-communist socio-economic situation.

The latter kind of nostalgia is arguably the result of a feeling of having lost out

in the transition from communism to democracy. The personal biography

dimension, on the other hand, has to do with personal feelings and memories

– whether authentic or not – of life under communist rule. Unfortunately, we

lack indicators of this dimension in our data set. Nevertheless, the importance

of the personal biography dimension must not be forgotten. In order to illus-

trate this point, one might draw attention to empirical observations in the

former German Democratic Republic (GDR), where scholars have noted

such revaluations of the past to be quite common among East Germans,

partly in response to the perceived threat of a West German depreciation of

their life experiences. Following unification, the East Germans certainly

have had their share of negative experiences with the new institutions. In

the early 1990s, unemployment skyrocketed in eastern Germany; suddenly

about one-third of all jobs were lost. But it has also to do with how East

Germans perceive that they and their past are being treated in post-Wende

Germany. For example, it has been noted that, following the collapse of the

GDR, East Germans have been going through a serious identity crisis. The

end of the GDR meant loss of self-esteem for many East Germans, and, as

a consequence, they experienced confusion and frustration. Literally over a

single night, all the things that had been taken for granted were no longer

valid. The East Germans were forced to adjust to a completely new environ-

ment, with new norms and conducts of behaviour in everyday life. West

German arrogance and disdain accompanied this transformation, or so the

East Germans perceived it. As a result of all of this, not a few have held on

to the belief that ‘not everything was bad’ under communism.6 Unique as

the East German road to democracy has been, a similar kind of retrospective

image of the ‘good old days’ may very well be expected to surface among the

citizens in other post-communist countries.

The four-dimensional classification (see Figure 1) may seem somewhat

simplistic, reducing the complex phenomenon of nostalgia to something

that could be quantified by a small number of discrete indicators. Still, since

this classification is compatible with a rather straightforward empirical

COMMUNIST NOSTALGIA IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE 357

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

investigation, we shall retain the model as a framework for the analysis in this

study. Simplistic or not, we would argue that our indicators tap the most

crucial aspects of ‘communist nostalgia’, and thus the model is of practical

use when examining the implications of communist nostalgia for the consoli-

dation of democracy on the attitudinal level. We also consider the opposite of

nostalgia in our analysis, namely belief in the future, conceptualized as

support for membership of the European Union.

A Note on the Empirical Material

Our main data source in this article is the New Europe Barometer (NEB), a

cross-national public opinion survey covering ten countries in Central and

Eastern Europe. We will also utilize the Eurobarometer and the Candidate

Countries Eurobarometer.

The specific NEB data set we have used actually consists of the New

Europe Barometer (2001) and its forerunners, the New Democracies Barom-

eter (1991–98) and the New Baltic Barometer (1993–2000), which have been

pooled together into one single data file containing some 62,000 respondents.

The number of face-to-face interviews is approximately 1,000 for each

country and year, which is sufficient to represent public opinion accurately

to within a few percentage units. Each sample has been drawn on a proportion-

ate-to-population basis, stratified by region, town size and urban–rural differ-

ences. Primary sampling units have been randomly drawn within each city or

rural area. Within each household, the respondent was chosen by a random

method, such as the pre-selection of a name from a popular register. The

surveys were conducted under the direction of Professor Richard Rose and

his research team at the Centre for the Study of Public Policy (CSPP), Uni-

versity of Strathclyde, in collaboration with established opinion research

institutes in the ten countries.7

The NEB survey questionnaire is explicitly designed for comparative ana-

lyses of public attitudes towards the democratic and market economic systems

in the post-communist countries. Thus, the NEB data set is arguably better

suited for our purposes than other comparable surveys, such as the Central

and Eastern Eurobarometer, the World Values Survey or the European

Social Survey, which contain relatively few items of interest if we wish to

analyse the development of system support throughout Central and Eastern

Europe. Even more important for the present investigation is the fact that

the NEB contains questions that can be found nowhere else, namely questions

that explicitly ask respondents about a return to communist rule. At the time of

writing, no other or more recent major cross-national opinion survey has

covered these aspects of democratic consolidation. In short, without the

2001 NEB data, the present investigation would not have been possible.

358 JOURNAL OF COMMUNIST STUDIES AND TRANSITION POLITICS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

The Presence of Nostalgia

Turning next to some empirical observations, we return to our main concern in

this article: does communist nostalgia constitute a threat to democratic consoli-

dation? Figure 2 and Figure 3 highlight the way in which post-communist citi-

zens have responded when asked about their relative preference for the present

democratic system compared with the former communist system. The item

reads: ‘Our present system of government is not the only one that this country

had. Some people say that we would be better off if the country was governed

differently. What do you think?’ The respondents are then asked whether they

strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree or strongly disagree to

the introduction of a number of non-democratic alternatives. In the figures

below, respondents in Central and Eastern Europe (see Figure 2) and the

Baltic countries (see Figure 3) are prodded about a ‘return to communist rule’.

In Central and Eastern Europe, this kind of ‘nostalgia’ is undoubtedly

present, albeit with significant cross-national variation. In 2001, the share of

nostalgic respondents ranged between 15 and 30 per cent. The general ten-

dency throughout the region is one of increasing levels of support for

a return to communist rule. In the period under review in Figure 2

FIGURE 2

APPROVAL OF A RETURN TO COMMUNIST RULE IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN

EUROPE (%)

Source: New Europe Barometer (2001).Note: The item has been dichotomized, and the percentages in the figure indicate the sum of

‘strongly agree’ and ‘somewhat agree’. ‘Don’t know’ and ‘No answer’ have been excluded.

COMMUNIST NOSTALGIA IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE 359

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

(1993–2001), only Bulgaria and Hungary display a minor decrease in this

respect. In the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, Slovenia and Romania,

the relative preference for a return to communist rule has increased by an

average of ten percentage points (1993–2001). Even in countries generally

perceived as consolidating democracies in the literature, such as the Czech

Republic, the share of respondents who feel that a return to communist rule

would be an acceptable idea has increased significantly.8

In Figure 3, the share of nostalgic respondents in the Baltic countries is

highlighted (1995–2001). There is a striking difference between the post-

Soviet states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania on the one hand, and the

Central and East European countries on the other. In the former group,

levels of communist nostalgia are generally lower, and never at any point in

time does the level of support for the old system rise above 15 per cent. It

may be noted that this does not necessarily indicate more widespread feelings

of support for the principles of liberal democracy in the Baltic countries, in

comparison with the countries of Central and Eastern Europe.9 Rather, we

would argue that the relatively low levels of communist nostalgia in

Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania reflect the post-Soviet status of these countries.

Given the strong emphasis on national self-determination in the Baltic

transformation processes in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it would be

entirely plausible to assume that ‘communism’ and ‘communist rule’ are

FIGURE 3

APPROVAL OF A RETURN TO COMMUNIST RULE IN THE BALTIC COUNTRIES (%)

Source: New Europe Barometer (2001).Note: The item has been dichotomized, and the percentages in the figure indicate the sum of

‘strongly agree’ and ‘somewhat agree’. ‘Don’t know’ and ‘No answer’ have been excluded.

360 JOURNAL OF COMMUNIST STUDIES AND TRANSITION POLITICS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

still intimately associated with lack of independence. In the countries of

Central and Eastern Europe analysed here, the problem of ‘statehood’ was

never a problem of the same magnitude.10

What we have in the Baltic countries, though, is perhaps what one could

designate ‘strong man nostalgia’. When asked in the autumn of 2001 about

their relative preference for that particular type of non-democratic alternative,

more than 39 per cent of the respondents in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania actu-

ally agreed to the statement that it would be ‘best to get rid of parliament and

elections and have a strong leader who can quickly decide everything’. In

comparison, the average support for ‘strong man rule’ in the Central and

Eastern European countries in our sample was 25 per cent in 2001.11

This could perhaps mean that ‘the good old days’ in the Baltic states refer

not to the communist era, but rather to pre-war history. Indeed, in a historical

perspective, independence is not only associated with the liberal democracy of

the 1990s: in the Baltic context, national independence is also associated with

the charismatic nation-builders of the inter-war era – Konstantin Pats, Karlis

Ulmanis and Antanas Smetona.12

It is an interesting question whether this kind of support for strong man

rule – apart from democracy, the only other known regime alternative to com-

munism – will survive in the years to come. There is arguably some evidence

to support the notion of Baltic respondents gradually learning to associate their

post-communist independence with the new, democratic systems. In Lithua-

nia, for example, the share of respondents who found strong man rule an

acceptable idea in 1993 hovered around 61 per cent; by 2001, the figure had

dropped to 40 per cent.13

A Threat to Democratic Consolidation?

So far, we have merely pointed out the presence of what we have referred to

here as communist nostalgia in Central and Eastern Europe, that is the relative

preference for the old, communist systems in comparison with the new demo-

cratic systems. As we have demonstrated, this kind of – for lack of a better

word – nostalgia is not ubiquitous. It would nevertheless be wise not to under-

estimate the system-destabilizing potential of such popular sentiments. Larry

Diamond, for example, suggests that the consolidation of democracy (on the

mass public level) ideally involves at least 70 per cent of the population

sharing the belief that democracy is preferable to any other form of govern-

ment.14 Before drawing any conclusions, however, we must stress again the

need to distinguish between different dimensions or aspects of communist

nostalgia (see Figure 1). It is far from obvious what Figure 2 and Figure 3 actu-

ally tell us about the prospects for democratic consolidation in the Baltic states

and in Central and Eastern Europe.

COMMUNIST NOSTALGIA IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE 361

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

Is nostalgia incompatible with the consolidation of democracy, then? Or,

to put it differently, does communist nostalgia – or, for that matter, strong man

nostalgia – actually reflect genuine non-democratic values, and consequently,

entail support for non-democratic alternatives?

A brief excursion on the concept of support is in order here. When analys-

ing support for any political system, we need to distinguish between different

objects of support. A useful model of system support has been suggested by

Pippa Norris.15 Drawing on David Easton, Norris distinguishes five levels

or objects of support: the political community, regime principles, regime per-

formance, regime institutions, and political actors.16 These different objects

are treated as existing on a continuum, ranging from diffuse support (for the

national community) to specific support (for particular political actors). The

first object in this five-part model, the political community, is not different

from Easton’s original concept. Diffuse support for the political or national

community indicates a basic attachment or a sense of belonging to a political

system. The distinction between ‘regime principles’ and ‘regime perform-

ance’ is made in order to account for the difference between support for

‘democracy’ as a principle or a normative ideal – as the best form of govern-

ment – and attitudes towards the way democracy works in practice, in a par-

ticular country at a given point in time.17 This distinction is, in other words, a

more sophisticated variant of Easton’s ‘regime values’. ‘Regime institutions’

is close to Easton’s notion of the ‘regime structure’. It concerns support for

political institutions, such as support for the constitutional function of a pre-

sidency rather than support for a particular president. It is worth noting,

however, that people may very well have different attitudes towards different

types of institutions. Lack of confidence in the parliament does not necessarily

entail lack of confidence in courts, the police or the bureaucracy, and so forth.

The final object, ‘political actors’, is similar to Easton’s ‘the authorities’. It has

to do with support for a particular person or a particular party.18

Returning to our examination of communist nostalgia, we shall use this

framework – the multidimensional model of support – when analysing

survey data and discussing system support. In terms of this model, we shall

look exclusively at two dimensions: support for democracy as a principle

and support for the performance of democracy. This distinction corresponds

fairly well to that between the political–ideological dimension and the

socio-economic dimension of communist nostalgia (see Figure 1).

Nostalgia, Age and Non-Democratic Values

How should we account for the presence of the phenomenon referred to here

as communist nostalgia? At least two hypotheses are possible. According to

the first hypothesis, communist nostalgia is above all the outcome of political

362 JOURNAL OF COMMUNIST STUDIES AND TRANSITION POLITICS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

socialization. When controlling for age, a clear division is to be expected.

Departing from the assumption that fundamental values are acquired in child-

hood and early adulthood, it would be entirely plausible to expect the older

respondents, socialized for decades in paternalistic, authoritarian societies,

to be more ‘nostalgic’ than the younger respondents, who have experienced

only the erosion and downfall of communism.19 According to the second

hypothesis, communist nostalgia is the result of distrust, disappointment, or

a combination of these, in the democratic system’s ability to produce

output. When controlling for age, a distinct generation or socialization

pattern is not to be expected. To the extent that differences between age

cohorts can be found, this has more to do with the realities of post-communism.

The transformation process has produced both winners and losers, and it is

likely that losers are more readily found among the older respondents – faced

today with poorly developed welfare arrangements and institutions – than

among the younger respondents, who following the collapse of communism

have gained new opportunities, and objectively could be classified as

winners of the transition. Since we are dealing with subjective perceptions of

the status as ‘winners’ and ‘losers’, however, a clear generation divide is not

necessarily to be found. Rather, nostalgia should be interpreted here, according

to the second hypothesis, as general discontent with what the newly installed

democratic regime delivers.20

We will start by looking at the socialization hypothesis. To begin with, we

need not bother with the nature of this phenomenon, that is, whether commu-

nist nostalgia indicates genuine non-democratic values, or simply reflects a

retrospective reassessment of life under communism. Rather, we want to

find out whether the age pattern is manifest or not.

In Table 1, we have analysed again the ‘communist nostalgia’ item (cf.

Figure 2), this time controlling for age. A clear pattern emerges: the older

the respondents, the more likely they are to approve of a return to communist

rule. Only Latvia, and to a lesser extent Estonia and Hungary, deviate from

this general pattern. In Estonia and Hungary, no straightforward relationship

between age and nostalgia is found. In Latvia, there is no difference at all

between the youngest and the oldest respondents in this respect. It may also

be noted that the levels of communist nostalgia among the young respondents

(18–29) do not exceed 20 per cent in any country. Among the old respondents

(50þ) the corresponding figures range between eight and 42 per cent

(Table 1).

However, we cannot from the figures in Table 1 alone draw conclusions

about the nature of this kind of communist nostalgia. We have noted that nos-

talgia is more common among the older generation. What about non-demo-

cratic sentiments? Does the age pattern in Table 1 imply that the younger

respondents have some kind of basic democratic mind-set, in contrast to the

COMMUNIST NOSTALGIA IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE 363

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

older respondents, socialized into an authoritarian frame of mind? Or, more

pointedly, would it make sense to speak about the presence of an ‘authoritarian

personality’ among the older citizens in post-communist Europe?21 By

‘authoritarian personality’ we mean a distinct human type

which has made a substantial negative contribution to politics in modern

times. The authoritarian personality is the one who introduces questions

of authority into all areas of social life, and in particular into areas where

they are inappropriate or unnecessary, with the result that nothing

happens by willing cooperation or natural sympathy, but only by

command and obedience.22

Although lacking an explicit measurement of the ‘authoritarian personal-

ity’, we do possess an indicator of the total opposite, namely an indicator of

public rejection of authoritarianism. Table 2 highlights the share of respon-

dents in Central and Eastern Europe who have firmly rejected all authoritarian

regime alternatives.

As before, an age pattern is manifest in Table 2. Save for Hungary, Lithua-

nia and Romania, a clear inverse relationship between age and rejection of

authoritarianism is found. The younger the respondents, the higher the likeli-

hood of rejection of all authoritarian alternatives. In other words, the notion of

the younger respondents having some kind of democratic mind-set seems to be

correct. By contrast, the older respondents stand out as sceptical towards

democratic government. This, in turn, could arguably be interpreted as the

outcome of long-term political socialization in various authoritarian systems.

At the same time, it must be noted that even among the oldest respondents

(50þ), a majority does not find any of the authoritarian alternatives very

TABLE 1

APPROVAL OF A RETURN TO COMMUNIST RULE BY AGE (%)

Country 18–29 30–49 50þ Total

Bulgaria 14 20 31 24Czech Republic 8 12 29 18Estonia 6 6 10 8Hungary 15 15 18 16Latvia 8 6 8 7Lithuania 12 14 15 14Poland 19 20 28 23Romania 13 15 24 19Slovakia 18 26 42 30Slovenia 18 22 26 23

Source: New Europe Barometer (2001).Note: The item has been dichotomized, and the percentages in the figure indicate the sum of‘strongly agree’ and ‘somewhat agree’. ‘Don’t know’ and ‘No answer’ have been excluded.

364 JOURNAL OF COMMUNIST STUDIES AND TRANSITION POLITICS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

attractive (see Table 2). It would thus be incorrect to assume that the older

generation of post-communist citizens en masse belong to some kind of

‘lost generation’ of deformed non-democrats, despising the present systems

and dreaming about the past. In fact, it could be argued that, as a rule, the citi-

zens of Central and Eastern Europe are very much oriented towards the future.

One indicator of belief in the future – and arguably the total opposite of

communist nostalgia – is support for the European Union (EU). Figure 4 high-

lights generalized support for membership of the EU (‘Generally speaking, do

you think that [our country’s] membership of the European Union would be a

good thing, neither good nor bad, or a bad thing?’). The bars in the figure indi-

cate the share of respondents who claim to support their own country’s mem-

bership of the EU (polled in October 2001 and February–March 2004). The

average level of support for the EU in Central and Eastern Europe – 52 per

cent in 2001 and 47 per cent in 2004 – should be contrasted with the corre-

sponding figures recorded among citizens in the 15 old member states,

where the average levels of support for membership of the EU was 48 per

cent, in both 2001 and 2004.23

Still, despite such widespread ‘euro-friendliness’ and belief in the future

among the respondents in Central and Eastern Europe (if not in the Baltic

countries), a pessimistic reading of Table 2 is possible as well. If we were

to use Diamond’s working definition of a consolidated democracy – which

stipulated that some 70 per cent of the citizens should have no reservations

about democracy as the preferred form of government – only two of our

TABLE 2

REJECTION OF AUTHORITARIANISM BY AGE (%)

Country 18–29 30–49 50þ Total

Bulgaria 67 60 48 56Czech Republic 85 80 65 75Estonia 64 63 53 60Hungary 75 76 72 74Latvia 68 65 56 61Lithuania 59 59 47 53Poland 63 60 56 59Romania 65 66 51 59Slovakia 72 63 48 60Slovenia 66 65 56 61

Source: New Europe Barometer (2001).Note: The respondents are presented with three non-democratic alternatives, and asked whetherthey agree or disagree to the introduction of these forms of government. The alternatives areas follows: ‘We should return to communist rule’, ‘The army should govern the country’,and ‘Best to get rid of parliament and elections and have a strong leader who can quicklydecide everything’. In Table 2, the figures indicate the share of respondents who have rejectedall these alternatives.

COMMUNIST NOSTALGIA IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE 365

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

ten countries (the Czech Republic and Hungary) would be considered conso-

lidated on the mass public level.24 Returning to the question of the relative

danger of communist nostalgia, we have seen that, to the extent that traces

of an authoritarian mind-set can be identified, it is chiefly a phenomenon

found among the older respondents. This generation divide could perhaps

be interpreted as a lingering effect of political socialization.

When analysing the development over time within each age category,

however, a somewhat ambiguous pattern is found. The general tendency of

increasing levels of nostalgia is found among the youngest as well as the

oldest respondents. For each of our ten countries, we have cross-tabulated

the respondents’ approval of a return to communist rule by age and year,

using the following age categories: 18–29, 30–49 and 50þ. In the 18–29

age group, we find increasing levels of nostalgia in nine out of ten countries.25

This is clearly not compatible with the socialization hypothesis. Even if we

find a general generation gap – the older respondents being more likely than

the young people to display feelings of nostalgia or sympathy for the commu-

nist era – we also find increasing levels of nostalgia among the youngest post-

communist citizens. This is not the outcome of political socialization under

communism, but something that has taken place in recent years. Furthermore,

looking at it from a different angle, this is not a problem that will take care

of itself. If communist nostalgia were to be found solely among the older

FIGURE 4

SUPPORT FOR MEMBERSHIP OF THE EUROPEAN UNION (%)

Source: Candidate Countries Eurobarometer (2001.1; 2004.1).

366 JOURNAL OF COMMUNIST STUDIES AND TRANSITION POLITICS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

respondents, it would be a phenomenon that would eventually disappear, as

time went by and the old people passed away.

Why would young people want a ‘return to communist rule’, then – people

who were only children in the 1980s? Does it make sense even to use the term

‘nostalgia’ in this case? Arguably, yes. Communist nostalgia, as understood

here (see Figure 1), does not necessarily presuppose thorough experiences

with life in a communist society. People who were not yet adults before

1989 can still think about the communist era as the ‘good old days’, since

they may share certain ‘collective memories’ or discourses about the past

today. Perceptions of the past are always influenced by experiences in the

present.

One can discriminate among three different observable ‘layers’ or aspects

of ‘collective memory’.26 The first aspect comprises ‘authentic’ memories –

for example, how an individual or a number of persons experienced a histori-

cal phenomenon, a time, a place, or a historical event. Only those who actually

experienced these phenomena at first hand could be said to have such ‘auth-

entic’ memories. This would apply to the middle-aged and the older respon-

dents in our sample. The second aspect of ‘collective memory’ has to do

with how these memories are being described, labelled or conceptualized in

society at large, in retrospect. For example, communism could be conceptual-

ized as ‘totalitarian rule’, as in the Latvian Occupation Museum in Riga,

where the atrocities committed against Latvians during the Nazi occupation

as well as during the Soviet era are documented. The third observable

aspect has to do with the wider framework of these ‘collective memories’ –

in what context are certain stories told, and for what purposes? In order to

rationalize, to come to terms with the past, or to legitimize specific policies

and actions?

Even those with no actual or authentic memories of a phenomenon, such as

Nazi terror or Soviet occupation, can be said to share a certain ‘collective

memory’, then, by taking part in the public discussion about this period, or

simply by passively accepting certain tales about the past. For example, the

belief that ‘not everything was bad’ under communism may be shared even

by people with only vague childhood experience of communist rule.

Nostalgia as General Discontent

Turning next to the loser–winner hypothesis, an alternative explanation for

the presence of communist nostalgia will be tested. As we have seen, age

alone is not sufficient to explain this phenomenon. In order to shed further

light on the dangers of this kind of nostalgia we need to find out whether

discontent with the present system’s ability to produce output is in fact a

more powerful determinant of communist nostalgia than non-democratic

COMMUNIST NOSTALGIA IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE 367

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

values. This has to do with the socio-economic dimension of communist

nostalgia (see Figure 1).

The assumption of discontent could perhaps be tested by examining the

respondents’ subjective perceptions of being losers or winners on the aggre-

gate (macro) level, by identifying whether society at large has benefited or

not from the transformation from planned economy to market. All assessments

must ultimately rest on comparison, and few are in a better position to judge

the market economy of the 1990s to the old socialist economy than the post-

communist citizens themselves. In the New Europe Barometer, the citizens of

Central and Eastern Europe were asked to evaluate how the old economic

system worked, on a scale from –100 to þ100. In Table 3, only the positive

assessments are displayed (þ1 to þ100).

Interestingly, we find that a majority of the post-communist citizens evalu-

ate the socialist economic order in rather favourable terms. Only the Czech

Republic stands out as a deviant case, where fewer than a third of the respon-

dents acknowledge the socialist economic system (see Table 3). As for the

development over time, this kind of ‘economic nostalgia’ has increased in

all countries, except for Lithuania. The age pattern we have encountered

above is visible here as well – the older the respondents, the more likely

they are to be nostalgic. Also, the increasing levels of nostalgia are most

evident among the oldest respondents (50þ).

When it comes to citizens’ evaluation of the post-1989 economic order, a

somewhat paradoxical pattern is found (Table 4). With the exception of

TABLE 3

EVALUATION OF THE SOCIALIST ECONOMIC SYSTEM (%)

Country

Positive evaluation2001 (Within brackets

change compared to 1991�)

Positive evaluation by age (2001)(Within brackets change compared

to 1991�)

18–29 30–49 50þ

Bulgaria 56 (þ26) 42 (þ23) 51 (þ23) 65 (þ29)Czech Republic 31 (þ8) 19 (þ1) 25 (þ5) 43 (þ13)Hungary 67 (þ16) 55 (þ8) 68 (þ18) 72 (þ17)Poland 61 (þ27) 53 (þ27) 62 (þ27) 65 (þ27)Romania 55 (þ29) 42 (þ20) 55 (þ29) 61 (þ30)Slovakia 61 (þ17) 48 (þ12) 58 (þ7) 72 (þ29)Slovenia 64 (þ26) 55 (þ6) 66 (þ23) 67 (þ33)Estonia 61 (þ13) 50 (þ4) 61 (þ14) 67 (þ15)Latvia 63 (þ15) 55 (þ5) 65 (þ15) 65 (þ18)Lithuania 54 (23) 50 (25) 55 (þ1) 56 (24)

�In the Baltic countries change is measured in comparison with 1993.Source: New Europe Barometer (2001).

368 JOURNAL OF COMMUNIST STUDIES AND TRANSITION POLITICS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

Slovaks and Lithuanians, we find that a majority of all respondents are

ready to endorse the current market economic system. At the same time, as

noted in Table 3, nostalgia for the socialist economic system was found

among a majority of the respondents as well. In other words, the average

post-communist citizen claims to be pleased with the present economic

system; but this positive evaluation does not presuppose a rejection of the

old economic system.

The figures in Table 3 could be interpreted as reflecting some kind of

socio-economic or performance-driven nostalgia. Still, the age pattern in the

table could at the same time be taken to reflect the outcome of political socia-

lization, and thus points to some kind of principle-driven nostalgia. In order to

confirm (or reject) the winner–loser hypothesis, we need to test the explicit

relationship between a perceived output deficit, communist nostalgia and

non-democratic values. In Table 5, we have tested the relative strength of

two performance items and one principle item, using ‘we should return to

communist rule’ as the dependent variable. We have also included the stan-

dard socio-demographic variables in the model.

The regression model clearly indicates that our performance items – ‘sat-

isfaction with the way democracy works’ and ‘satisfaction with the current

economic situation of one’s household’ – have more predictive power than

the item relating to principle (‘A unity government with only the best

people should replace government by elected politicians’). In other words,

communist nostalgia seems to be a phenomenon related to dissatisfaction

TABLE 4

EVALUATION OF THE CURRENT ECONOMIC SYSTEM (%)

Country

Positive evaluation 2001(Within brackets change compared

to 1991�)

Positive evaluation by age (2001)(Within brackets change compared

to 1991�)

18–29 30–49 50þ

Bulgaria 63 (21) 72 (28) 70 (þ2) 55 (22)Czech Republic 76 (þ5) 81 (þ5) 77 (þ7) 74 (þ5)Hungary 76 (þ18) 78 (þ20) 74 (þ16) 75 (þ20)Poland 66 (þ15) 69 (þ19) 69 (þ15) 62 (þ11)Romania 50 (219) 51 (216) 51 (220) 50 (220)Slovakia 38 (212) 46 (þ4) 37 (218) 34 (217)Slovenia 75 (þ26) 80 (þ26) 74 (þ26) 73 (þ24)Estonia 69 (þ15) 73 (þ13) 71 (þ15) 65 (þ17)Latvia 52 (þ11) 67 (þ21) 54 (þ18) 45 (0)Lithuania 46 (22) 51 (þ2) 47 (21) 44 (25)

�In the Baltic countries change is measured in comparison with 1993.Source: New Europe Barometer (2001).

COMMUNIST NOSTALGIA IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE 369

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

with the present system’s ability to deliver the goods – material or non-

material – rather than a phenomenon reflecting some kind of ‘legacy of the

past’. This finding supports the second hypothesis in the sense that communist

nostalgia above all seems to be the outcome of a perceived lack of system

output.

As for the socio-demographic variables, only education stands out as rela-

tively important, which could be interpreted as yet another indication of the

validity of the second (performance) hypothesis. The higher the level of edu-

cation, the less likely the respondents are to approve of a return to communist

rule. This in turn ties in neatly with the winner–loser argument. It is also inter-

esting to note that when controlling for other variables (see Table 5), the

relationship between age and communist nostalgia loses much of its import-

ance (cf. Tables 1 and 2).

Conclusions

To summarize the findings of this study, communist nostalgia is clearly a mul-

tidimensional phenomenon. On the one hand, we have found that nostalgia is

indeed related to age. The older the respondents, the more likely they are to

express feelings of nostalgia for the old, communist system (see Table 1).

This could be taken to support the notion of generational differences and

the existence of non-democratic values as brought about by political sociali-

zation under communism. On the other hand, our findings indicate that

TABLE 5

APPROVAL OF A RETURN TO COMMUNIST RULE: REGRESSION ANALYSIS

Independent variables Beta t Sig

Satisfaction with democracy 2.146 29.930 .000Economic situation 2.074 24.660 .000Support for elite rule 2.037 22.618 .009Income 2.089 25.495 .000Town size 2.064 24.279 .000Education 2.125 27.852 .000Age .014 .994 .320Gender .049 3.492 .000Adjusted R2 ¼ .254

Source: New Europe Barometer (2001).Note: Dependent variable: ‘We should return to communist rule’ (1 ¼ strongly disagree, 4 ¼strongly agree). Independent variables: ‘Satisfaction with democracy’ (1 ¼ very dissatisfied,4 ¼ very satisfied); ‘Satisfaction with the current economic situation of household’ (1 ¼ verydissatisfied, 4 ¼ very satisfied); ‘A unity government with only the best people should replacegovernment by elected politicians’ (1 ¼ strongly disagree, 4 ¼ strongly agree); ‘Income’(quartiles, 1 ¼ lowest, 4 ¼ highest); ‘Town size’ (1 ¼ small village, 13 ¼ Capital); ‘Age’ (Fivecategories); ‘Gender’ (Male ¼ 1, Female ¼ 2).

370 JOURNAL OF COMMUNIST STUDIES AND TRANSITION POLITICS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

nostalgia is mainly output-oriented. When looking at the determinants of

the phenomenon referred to here as communist nostalgia, we find that our

performance items have significantly more explanatory power than the

principle item used here (see Table 5).

An overriding concern in this article relates to the consolidation of democ-

racy on the attitudinal level in Central and Eastern Europe, and the question

we are interested in is whether or not the kind of nostalgia we are dealing

with here poses a threat to democratic consolidation. In the literature, there

is no agreement on this issue in general. Some scholars claim that, in order

for democracy to be considered ‘the only game in town’, a majority of the

population should firmly reject the old non-democratic type of regime.

Others have taken a more pragmatic stance, arguing that there is no immediate

need for people in general to reject the non-democratic past altogether, as long

as they lend sufficient support for the new, democratic regime.27

All in all, our findings in this article go well with the second of these per-

spectives. Communist nostalgia, as understood here, does not pose a direct

threat to democracy in post-communist Europe today. Even if we find a dis-

turbing pattern – increasing levels of communist nostalgia in recent years

(see Figures 2 and 3) – this is clearly not a phenomenon that goes hand-

in-hand with a total rejection of the advantages of liberal democracy (see

Tables 2 and 4). This may seem somewhat contradictory. Communist nostal-

gia, however, clearly encompasses more than just non-democratic principles.

We have noted here that nostalgia above all spells general discontent, moti-

vated by a perceived output deficit. It is also likely that nostalgia is brought

about by such factors as personal memories of life under communism. This

may include a number of selective memories of ‘what it was really like’ in

the good old days, as well as retrospective revaluations. Moreover, it is

quite understandable if the post-communist citizens express some kind of

sympathy for the old days, considering the realities of the democratization

processes. The simultaneous political and economic transformation has been

no stroll in the park. Political freedom is welcomed, but the economic

changes are sometimes considered unfortunate. Even if only the occasional

die-hard Stalinist misses the totalitarian order, quite a few post-communist

citizens may miss the security of the past, when they knew that they would

get a pension they could live on and when they did not have to worry about

jobs, prices or rents. The psycho-social effects of the substantial changes in

the 1990s have been described in the literature as nothing short of a ‘cultural

shock’.28

At the same time, one should perhaps not underestimate the potential

danger of ‘communist nostalgia’ (see Table 5, Figures 2 and 3). If nostalgia

is the result of disappointment in the democratic system’s ability to produce

output, and at the same time this kind of discontent is increasing, it may in

COMMUNIST NOSTALGIA IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE 371

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

the end constitute a substantial challenge to the legitimacy of democracy in

post-communist Europe.29 Former communist parties may or may not gain

from such public dissatisfaction, but it would be more accurate to say that

protest parties in general may capitalize on such sentiments.30 Then again,

this is of course not something that is unique to Central and Eastern

Europe. In fact, the democratic regimes that were installed following the

demise of communism have been able to cope with a number of significant

challenges in the 1990s, and the relevant question today does not concern

the risk of democratic breakdown. Rather, it is a question of creating as

favourable conditions as possible for the practical realization of democracy.

This process, usually referred to in the literature as the consolidation of

democracy, is not fundamentally different from the day-to-day process of

coping with the challenges to democracy in Western Europe. The main

concern regarding the future development of democracy – in Europe as a

whole – relates to the deepening of democracy in the face of European inte-

gration, globalization, the rise of xenophobia and societal fragmentation, to

mention just a few challenges to democracy in contemporary Europe. The

post-communist citizens may be ever so critical, sceptical, dissatisfied and

disappointed. Still, a majority of them support the principles of democracy

just the same.

NOTES

1. Ronald Inglehart, ‘Political Culture and Democratic Institutions: Russia in Global Perspec-tive’, paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association(2000), p.17.

2. See, for example, Juan J. Linz and Alfred Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition andConsolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe (Baltimore,MD and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996); Richard Rose, William Mishlerand Christian Haerpfer, Democracy and Its Alternatives: Understanding Post-CommunistSocieties (Baltimore, MD and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998); LarryDiamond, Developing Democracy: Toward Consolidation (Baltimore, MD and London:Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999); Jonas Linde, Doubting Democrats? A ComparativeAnalysis of Support for Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe (Orebro: OrebroStudies in Political Science 10, 2004).

3. See Linde, Doubting Democrats?, pp.256–8.4. Andreas Schedler, ‘What is Democratic Consolidation?’, Democratization, Vol.9, No.2

(1998), pp.91–107.5. Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language (Cologne:

Konemann, 1993).6. See, for example, Thomas Bulmahn, ‘Taking Stock: German Unification as Reflected in the

Social Sciences’, Discussion Papers FS III 98–407 (Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin furSozialforschung, 1998); Joakim Ekman, National Identity in Divided and Unified Germany:Continuity and Change (Orebro: Orebro Studies in Political Science 3, 2001). One aspect ofnostalgia that we have failed to discuss in this article, related to the personal biography dimen-sion (see Figure 1), concerns nostalgia as consumption. There are plenty of examples from allover Europe of this phenomenon. Young people are drawn to communist memorabilia by thekitsch factor of the communist aesthetic: Lenin T-shirts, Pioneer shirts, badges, brands (like

372 JOURNAL OF COMMUNIST STUDIES AND TRANSITION POLITICS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

the Ostalgie products in the former GDR), CDs with official communist sing-along songs, andso forth. Such an interest in communist products may be seen as ironic mockery as well as apost-modern search for identity. At the more extreme end of the spectrum we find communisttheme parks, such as businessman Blasko Gabric’s ‘Yugoland’, located in Subotica, a smallnorthern Serbian village, or the memorial site in Grutas Park, southern Lithuania (unofficiallynamed ‘Stalinworld’), where some 75 statues of Lenin, Stalin, Marx and Engels have beenpreserved. The construction of a similar theme park in Berlin has been seriously discussedas well. Such cultural–commercial expressions are of course interesting, but not reallyimportant when analysing the prospects for democratic consolidation.

7. We are most grateful to Professor Sten Berglund (Orebro University, Sweden) and ProfessorRichard Rose (University of Strathclyde, UK) for allowing access to this valuable data set:New Europe Barometer, Machinereadable datafile, Conditions of European Democracy,Orebro University and Centre for the Study of Public Policy (CSPP), University of Strathclyde(2001).

8. See, for example, Sten Berglund, Frank H. Aarebrot, Henri Vogt and Georgi Karasimeonov,Challenges to Democracy: Eastern Europe Ten Years After the Collapse of Communism(Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2001), pp.120–21; Terry D. Clark, Beyond Post-CommunistStudies: Political Science and the New Democracies of Europe (New York: M.E. Sharpe,2002); Joakim Ekman, Sten Berglund and Frank H. Aarebrot, ‘Concluding Remarks’, inSten Berglund, Joakim Ekman and Frank H. Aarebrot (eds.), The Handbook of PoliticalChange in Eastern Europe, 2nd edn. (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2004).

9. See Linde, Doubting Democrats?, pp.211–36.10. See Ekman, Berglund and Aarebrot, ‘Concluding Remarks’, pp.599–605.11. New Europe Barometer.12. Kristian Gerner and Stefan Hedlund, The Baltic States and the End of the Soviet Empire

(London and New York: Routledge, 1993), pp.57–8.13. New Europe Barometer.14. Diamond, Developing Democracy, p.68; compare Linz and Stepan, Problems of Democratic

Transition and Consolidation, p.6.15. Pippa Norris, ‘Introduction: The Growth of Critical Citizens?’, in Pippa Norris (ed.), Critical

Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1999), pp.1–27.

16. The five-part model suggested by Norris should be compared to Easton’s well-known typol-ogy: see David Easton, A Framework for Political Analysis (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1965); David Easton, ‘A Re-assessment of the Concept of Political Support’, BritishJournal of Political Science, Vol.5 (1975), pp.435–57.

17. See Jonas Linde and Joakim Ekman, ‘Satisfaction with Democracy: A Note on a FrequentlyUsed Indicator in Comparative Politics’, European Journal of Political Research, Vol.42,No.3 (2003), pp.391–408.

18. Norris, Critical Citizens, pp.9–12; Hans-Dieter Klingemann, ‘Mapping Political Support inthe 1990s: A Global Analysis’, in Norris (ed.), Critical Citizens, pp.33–8.

19. On childhood socialization, see, for example, Ronald Inglehart, The Silent Revolution:Changing Values and Political Styles (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977).

20. See Linde and Ekman, ‘Satisfaction with Democracy’, pp.391–408.21. The classic work on authoritarian values is Theodor W. Adorno, The Authoritarian Person-

ality (New York: Free Press, 1950).22. Roger Scruton, A Dictionary of Political Thought (London: Macmillan, 1996), p.35.23. Candidate Countries Eurobarometer 2001.1 (Brussels: European Commission, 2002), field-

work: October 2001; Candidate Countries Eurobarometer 2004.1 (Brussels: European Com-mission, 2004), fieldwork: February–March 2004; Eurobarometer 61 (Brussels: EuropeanCommission, 2004), fieldwork: March 2004.

24. Diamond, Developing Democracy, p.68.25. We have analysed the development from 1993 to 2001 in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic,

Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia; in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, theNEB time series runs from 1995 to 2001.

COMMUNIST NOSTALGIA IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE 373

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013

26. Mary Fulbrook, German National Identity after the Holocaust (Cambridge: Polity Press,1999), pp.143–6; Peter H. Merkl, ‘German Identity Through the Dark Mirror of the War’,in Peter H. Merkl (ed.), The Federal Republic of Germany at Fifty: The End of a Centuryof Turmoil (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1999), p.341.

27. Geoffrey Pridham, ‘Confining Conditions and Breaking with the Past: Historical Legacies andPolitical Learning in Transitions to Democracy’, Democratization, Vol.7, No.2 (2000),pp.36–64; Alexandra Barahona De Brito, Carmen Gonzalez-Enriques and Paloma Aguilar(eds.), The Politics of Memory: Transitional Justice in Democratizing Societies (Oxford:Oxford University Press, 2001); Rose, Mishler and Haerpfer, Democracy and Its Alternatives;Linz and Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation; see also Diamond,Developing Democracy, pp.178–85; Linde, Doubting Democrats?

28. Wolf Wagner, Kulturschock Deutschland (Hamburg: Rotbuch Verlag, 1996); see also WolfWagner, Kulturschock Deutschland: Das zweite Blick (Hamburg: Rotbuch Verlag, 1999).Similar accounts of the difficulties involved in the transformation process, and retrospectiverevaluations of life under communism, can be found in the rich flora of personal recollectionsof life in the GDR. In the wake of the German unification, the field of Alltagsgeschichte hasemerged as an interesting branch of GDR history. In the 1990s and early 2000s, a largenumber of books have been written, describing various aspects of everyday life in theGDR. Such ‘oral history’ studies or ‘life stories’ make up a vast body of documents, andshould be regarded as rather important for our understanding ‘communist nostalgia’ andpost-communist public opinion. A recent study that touches upon such issues from a socio-logical point of view is Carol Harrington, Ayman Salem and Tamara Zurabishvili (eds.),After Communism: Critical Perspectives on Society and Sociology (New York: Peter Lang,2004).

29. See Easton, A Framework for Political Analysis.30. Ekman, Berglund and Aarebrot, ‘Concluding Remarks’, pp.599–605.

374 JOURNAL OF COMMUNIST STUDIES AND TRANSITION POLITICS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cen

tral

U L

ibra

ry o

f B

ucha

rest

] at

05:

43 3

1 M

ay 2

013