Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

-

Upload

lisa-woods -

Category

Documents

-

view

227 -

download

0

Transcript of Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

1/36

PROJECT REPORT

2010 - 2011

MSc Public Health

Stream: Health Promotion

Title: Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

Supervisor: Adam Biran

Candidate Number: 100822 Word Count: 9,277

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

2/36

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................. .................. .................. ................. .................. .................. .................. ...3

EXCUTIVESUMMARY....................................................................................................................................4 1.INTRODUCTION .................. .................. .................. .................. ................. .................. .................. ............62.AIMSANDOBJECTIVES............................................................................................................................82.1AIM ...............................................................................................................................................................8 2.2OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................................................................................8

3.BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................83.1THESLUMCONTEXT .....................................................................................................................................8 3.2GOVERNMENTAPPROACHCESTOSLUMSANDITSIMPACTONSANITATION ............................................8

3.3COMMUNALLATRINEPROVISIONINAFRICANSLUMS ................................................................................9 3.4GOODPRACTICESINTHECOMMUNITYMANAGEMENTOFCOMMUNALLATRINES ................................. 104JUSTIFICATIONANDKEYQUESTIONS .............................................................................................. 115.MATERIALSANDMETHODS ............................................................................................................... 115.1SEARCHSTRATEGY.................. .................. .................. ................. .................. .................. .................. ...... 11

5.2DATACOLLECTIONTOOLS ................ .................. .................. ................. .................. .................. ............... 125.3SAMPLING ............... .................. .................. .................. .................. ................. .................. .................. ...... 156.COMMUNALLATRINEPROVISIONINLIBERIANSLUMSACASESTUDY............................ 166.1INTRODUCTION .................. .................. .................. .................. ................. .................. .................. ............ 15

6.2NATIONALSANITATIONPRIORITIES ................. ................. .................. .................. .................. ............... 15

6.3POLICYENVIRONMENTANDINSTITUTIONALFRAMEWORK.................................................................... 177.RESULTS .................................................................................................................................................... 197.1NUMBEROFPAYINGUSERS .................. .................. .................. ................. .................. .................. ............ 197.2PHYSICALCONDITIONSANDOPERATINGCHARACTERISTICSOFFACILITIES .......................................... 207.3SOCIALANDECONOMICCHARACTERISTICSOFCOMMUNALLATRINEUSERS .......................................... 217.4HOUSEHOLDLATRINEOWNERSHIP ................. .................. ................. .................. .................. .................. 227.5HOUSEHOLDRESSOURCES................. .................. .................. ................. .................. .................. ............... 21

7.6PATTERNSOFUSEREPORTEDBYCOMMUNALLATRINEUSERS ........................................................... 21

7.7CHILDRENANDCOMMUNALLATRINEUSE ................. ................. .................. .................. .................. ...... 21

7.8PAYMENTANDWILLINGNESS-TO-PAY.................. ................. .................. .................. .................. ............ 247.9SANITATIONACCESSANDPLANSFORFUTURE USEOFCOMMUNALLA TRINES ....................................... 257.9.1COMMUNALLATRINEUSERSSATISFACTIONWITHTHEFACILITIES .................................................... 268.DISCUSSION...26

9.CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................ 3210.RECOMMENDATIONS ......................................................................................................................... 33

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

3/36

3

ACRONYMS

CBO Community Based OrganisationGoL Government of LiberiaIDP Internally Displaced PersonI/NGO International/Non-governmental Organisation

JMP Joint Monitoring ProgrammeLWSC Liberia Water & Sewerage CorporationMDG Millennium Development GoalMoHSW Ministry of Health and Social WelfareOHCHR Office of the High Commissioner for Human RightsO&M Operation and ManagementPLWHA People Living with HIV/AIDSPRS/P Poverty Reduction Strategy/PaperSSP Slum Sanitation ProgrammeUN-Habitat United Nations Human Settlements ProgrammeUNICEF United Nations Childrens Fund

UN United NationsUNMIL United Nations Mission in LiberiaWASH Water, Sanitation, and HygieneWHO World Health OrganizationWSSP Water Supply and Sanitation Policy

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

4/36

4

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Acknowledgement of academic support

I would like to express my gratitude to all who have assisted with this project and helped

make it a success.

Project development: The idea for this project was shaped after several discussions withLSHTM professors in the Department of Disease Control. The focus was sharpened aftermeeting my supervisor who suggested that I concentrate on aspects of the communitymanagement of communal latrines and its impact on use. Professor Claire Snowden alsohelped refine my qualitative research tools.

Contact, input and support: I met with my supervisor three times to develop the researchprotocol and to discuss issues regarding ethical approval in a post-conflict country. We hadfurther email exchanges to develop and refine my household survey and other research

tools. I proposed the project to several INGOs and Yael Velleman (WaterAid UK) forwardedmy proposal to Oxfam GB in Liberia, which is the lead agency of the Liberia WASHConsortium. The Consortium believed the research would prove useful to the WASH sectorand agreed to host the research. In Monrovia I was based in the office of ConcernWorldwide Liberia, which provided practical advice, administrative and logistical support. Iintermittently contacted my supervisor by email to discuss issues in the field, initial findingsand the first draft of the report. Financial support for the fieldwork was obtained from theSchool Trust Funds, Bob Holt (The Mears Group), Prasad Gollakota (UBS), Thomas LiloJoycutty (HSBC), and Dr. Nelda Frater (The Frater Clinic). Unpublished documents andinformation was provided by Jenny Lamb and Andy Bastable (Oxfam GB), Yael Velleman(WaterAid UK), Madeleen Wegelin (IRC), David Kuria (Ikotoilet) and Aytor Naranjo.

Encouragement and emotional support was provided by my dear friend and colleague Dr.Thomas Burke (Partners HealthCare).

Main research work: I identified all references through my own desk review. In Liberia, Isupervised the data collection of six-community based enumerators. I carried out keyinformant/group interviews, latrine observations and transect walks.

Writing-up: My supervisor read notes from my field research and made comments andinquiries. He also read my first full draft of which no major revisions were required.

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

5/36

5

Executive Summary

Communal latrines are an inadequate policy response to the sanitation crisis of sub-Saharan

Africas urban poor. It is estimated that 180 million African urbanites have no access to

sanitation and if current demographic trends persist, a majority of the African population will

reside in urban areas by 2015. This will result in slum densification and increase the urban

need for sanitation by 50 per cent. Humanitarian organisations have responded by providing

community-managed communal latrines in urban slums.

The overall aim of this policy report is to investigate communal latrine provision as a policy

response to inadequate sanitation and endemic cholera in urban slums in the West African

country of Liberia. It examined communal latrine provision in the Billimah, New Kru Town

and Zinc Kamp slums of Monrovia where each community has two communal latrine blocks

built by Concern Worldwide Liberia as part of its cholera response. The facilities have six

pour-flush toilets that are connected to a septic tank. The toilets function independent of

water, electricity and sewerage, and a community-based WASH Committee undertakes

operation and maintenance (O&M) of the facilities. A household survey in which 79

respondents were interviewed was conducted to ascertain user satisfaction and to explore

communal latrine usage rates, characteristics of users and non-users, and evidence for any

groups being systematically excluded. Multiple methods of inquiry were used to triangulate

the findings and strengthen the scientific argument for validity.

The study sought to answer whether communal latrines significantly reduced open

defecation in Liberian slums. While adult respondents have benefitted from the provision of

communal latrines, young children have been largely excluded because of cost and societal

acceptance of open defecation amongst children. Although usage rates amongst the adult

population were reportedly high, there was an even larger portion of the target population not

using the latrine. The findings suggest that the manner and scale that communal latrines

have been provided in Monrovian slums is not sufficient to stop open defecation.

The study also questioned whether the community management of communal latrines was

sustainable. The findings suggest that the technical design has made it difficult for

community-based WASH Committees to maintain the latrines as communities reported too

small, overburdened septic tanks that leak raw sewage into the roads. The WASH

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

6/36

6

Committees cannot mitigate this environmental and public health risk without substantial

external assistance. Furthermore, the current design is not environmentally sustainable

because the sewerage network does not function properly and vacuum tanks are obliged to

empty septic tank contents untreated into the sea.

These management challenges are handled by the WASH Committees alone each having

varying levels of skill and motivation. The inability of the New Kru Town WASH Committee to

resolve a conflict resulted in the community being locked out of the communal latrines for

nearly five months. The Zinc Kamp WASH Committee was unable to find a caretaker for four

months and the facilities sat unused while the target population continued promiscuous

defecation. Each community reported that the user fees were not enough to empty the septic

tank when it first fills. These findings imply that the current management structure gives the

community too much responsibility in the O&M of the toilets without sufficiently building local

capacity to solve problems. This adversely affects use and threatens the sustainability of the

latrines.

Communal latrines as a policy response to poor sanitation in Monrovian slums have

shortfalls that can only be overcome if the factors for sustainability are systematically

addressed. Concern Liberia and partners should build the capacity of WASH Committees

through standardised trainings to ensure a basic level of knowledge and skills. Gender

equity should be promoted to ensure that the communal latrines are responsive to the needs

of mothers and children. A sanitation demand should be stimulated through social marketing

activities that replace the disease-driven approach to sanitation provision. There is also a

need to advocate with municipalities for a reduced rate to empty septic tanks in slum

communities. These recommended actions would greatly improve the sustainability of the

community-managed communal latrines, and reduce the sanitation-related disease burden

of the communities.

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

7/36

7

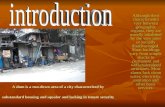

1. Introduction

Communal latrine provision as a solution to sanitation in sub-Saharan African slums is a

weak policy response to the sanitation crisis of the urban poor.

Globally 2.6 billion people lack access to improved sanitation about three quarters of who

reside in sub-Saharan Africa (hereafter Africa).1 A lack of access to the safe disposal of

human excreta has traditionally been worse in rural areas but a majority of the African

population is expected to reside in urban areas by 2015, increasing the urban need for

sanitation by 50 per cent.2 In Africa, urbanisation is synonymous with slum densification as

the region has an annual slum growth rate more than double the global average (4.53% per

annum). Currently about 80% of urban dwellers in poorer African countries reside in slums

and Africa is expected to have the highest number of slums by 2020.3

Challenges to providing sanitation in African slums are broad. Sanitation has been severely

underfinanced; there has been little investment into the research and development of cheap

sanitation innovations; it is expensive to import northern technologies; and national

sanitation policies fragment responsibilities across institutions. The aforementioned factors

result in a weak foundation for national sanitation provision in both urban and rural areas.

Urban sanitation has been further challenged by rapid urbanisation that has outpaced the

provision of water and sewerage pipes, poor governance, a lack of political will, a failure to

recognise and provide service to informal settlements and decentralisation with insufficient

capacity building at the local level.

State and non-state providers have responded to the sanitation crisis through the provision

of communal or shared latrines. This policy report will focus on communal latrine provision

as an international non-governmental organisation (INGO) response to inadequate sanitation

in African slums. While communal latrines do not meet the World Health Organization/United

Nations Childrens Fund Joint Monitoring Programme (WHO/UNICEF JMP) definition of

improved sanitation* it is the most common means by which humanitarian agencies aim to

reduce open defecation and the unsafe disposal of human excreta in the slums.

* JMP: An improved sanitation facility is one (private or shared with a reasonable number of people) thathygienically separates human excreta from human contact. Communal latrines are not considered improvedsanitation.

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

8/36

8

2. Aims and objectives

2.1 Aim

The overall aim of this policy report is to investigate communal latrine provision as a policy

response to improve sanitation amongst urban slum dwellers in Liberia.

2.2 Objectives

The objectives were to:

1. Summarise existing knowledge regarding communal latrines and other low cost

technologies with a focus on how management and fee structures impact

sustainability.

2. Carry out a case study of a select communal latrine in a cholera-endemic Monrovia

slum to explore usage rates, characteristics of users and non-users, and evidence of

any groups being systematically excluded.

3. Highlight good practices in communal latrine provision in select African slums

including latrine design/user fees/ cleanliness/ maintenance/ distance/ opening

times/gender sensitivity/child friendliness and how these features impact use.

4. Critically review the policy of (communal) sanitation provision in Monrovia slums in

light of the desk and field research, and make recommendations relating to urban

slum sanitation policy.

5. Make policy recommendations to the Liberia WASH Consortium and the Liberia

Water and Sewer Corporation based on evidence from field research and selected

good practices on sanitation provisions in the slums.

3. Background

3.1 The slum contextThe United Nations Expert Group Meeting in Nairobi (2000) defined a slum as a contiguous

settlement where the inhabitants are characterised as having inadequate housing and basic

services. A slum is often not recognised and addressed by the public authorities as an

integral or equal part of the city.4 Slums can be found on the land that nobody wants such

as rubbish heaps, swamps, and other unsafe areas. Strategic settling provides some

protection against eviction but also increases the populations risk to infectious diseases and

makes it difficult to find an appropriate sanitation solution. Because of the mainstay features

of the slums, there is little sanitation demand, as poor tenants may fear that an investment in

sanitation will result in an unaffordable rent hike, and landlords do not feel compelled to offer

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

9/36

9

household latrines.5 A lack of sanitation coupled with other environmental factors is

associated with the high levels of ill health found by Rhaman et al (1980)6 in the Dhaka

slums; and Gulis et al (2003)7 in the Nairobi slums.

3.2 Government approaches to slums and its impact on sanitation

Arimah et al (2010) conceptualised three ways in which African States have dealt with

slums: Benign neglect, forced eviction/demolition, and resettlement/upgrading. Each

approach has implications for sanitation provision. Countries adopting the approach of

benign neglect have deemed slums illegal, temporary and prone to disappearance with the

financial growth of the country. Settlements with illegal status are often not serviced by

municipal authorities and have no access to credit because their homes cannot be used for

collateral.8

In a resettlement situation, families are allocated land in which they are expected

to build their own houses (or low-cost housing is provided), and the burden of sanitation falls

on the household. In slum-upgrading programmes the environment is targeted for

improvement and communal latrines are typically provided.

3.3 Communal latrine provision in African slums

The provision and management of communal latrines varies according to context. In African

slums a common practice is for community members to pay at the point of use or to gain

access through the purchase of a monthly card. The structures are often built by I/NGOs or

government agencies that either lease the latrines to private contractors, or donate them to

the community to manage. User fees pay the caretaker who maintains the toilet block on a

daily basis. Fees also pay the municipality or private contractor that empties the pit/tank.

This fragmentation has profound implications for partnerships, because it is very difficult to

link the three segments and their role players into the delivery chain needed for effective

service delivery.9 Communities are then expected to take ownership of facilities that have

no institutional home, accountability or oversight. The end result is that facilities often fall into

disrepair and disuse even in sanitation-stressed areas.10

Research has found that communal latrines are often just receptacles for excreta 11 that are

inaccessible and unresponsive to the needs of the target population because of issues

related to cost, access, security and overuse.12 In Harare, Zimbabwe 1,300 people are

supposed to share six seats. In Kibera, Nairobi, 190 shared facilities serve a population of

250,000 (1:1300 users).13 In Nairobi slums women have reportedly been raped en route to

Health problems found included intestinal problems, measles, fever, skin diseases, chronic respiratory

infections.

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

10/36

10

the communal latrine.14 Researchers have found that mothers sometime worry that children

will catch diseases from adult faeces on toilet slabs and fear that small children will fall into

poorly designed toilets.15 These aforementioned factors discourage use and open defecation

is still prevalent in communities where communal latrines are provided.

3.4 Good practices in the community management of communal latrines

Progressive community-based organisations (CBOs) have introduced community

management schemes that have a wider focus than simply providing toilet seats. The CBO,

Umande Trust, built 20 communal bio-sanitation centres in the Kibera, Nairobi slum the

largest being the Katwerkera Tosha Bio Centre. The facilities were found to be sustainable in

a number of ways when evaluated against ten criteria put forth in the Good Practices

Related to Access to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation outlined by the Office of the High

Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).16,

Community processes to build and operate the bio-centres were found to promote

democracy and inclusiveness through the engagement of already-established community

groups that select sites of the bio-centres and manage services. The community groups

directly profit through a community-shareholding scheme in which 60% of the fees are

allocated to members as dividends; 30% pays for the O&M of the facility; and 10% is

deposited in a sanitation development fund.17 The technology of the bio-centres is equally

important as communities do not have to spend money to empty pits/septic tanks as the

toilets are connected to a bio-digester in which biogas is produced. Collectively the bio-

centres service about 12,000 users per day.

Another example of a good practice is the Greater Mumbai Slum Sanitation Programme

(SSP), which focuses on building strategic partnerships for the successful community

management of communal latrines.18 Under the SSP, NGOs lead a community-wide

consultative process, which results in the formation and registration of CBOs in sanitation-

stressed areas. Families must express demand through the contribution of a small

membership fee.** CBO members provide assistance and oversight of the latrine

construction throughout the building process. The integrated contracts feature of the SSP

formally links all actors in the provision of communal latrines in the slums. Unifying the

fragmenting service delivery of communal latrine provision in the slums, generating demand

Ten criteria include: availability, accessibility, affordability, quality/safety, acceptability, non-discrimination,

participation, accountability, impact, and sustainability.TV/video room, caf, clinic, water kiosk, meeting rooms

**The fee is Rs.100 per adult (US $2.25) (up to a maximum of Rs. 500 (US $11.25) per family.

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

11/36

11

for sanitation at the household level, and introducing mechanisms for the accountability and

regulation of the structures, provides the necessary conditions for the management of

communal latrines in the slums.19

4 Justification and key questions

Access to the safe disposal of human excreta is a fundamental human right that

protects health and upholds human dignity. Liberia has a population of 3.6 million

and nearly 2.9 million lack access to improved sanitation. The sanitation situation has

been affected by the countrys two brutal civil wars that spanned over a 14-year

period from 1989 to 2003. Pre-war sanitation coverage was 27% but a massive

influx of people into the capital of Monrovia, along with destruction of the nations

infrastructure and WASH institutions reduced national sanitation coverage to 17%.

Inadequate sanitation is the key protagonist in a web of interrelated diseases

such as diarrhoea, malnutrition, acute respiratory infections and endemic

cholera. Cholera is endemic in Monrovia and about 888 cumulative

(suspected) cholera cases occurred from 31 Dec 2008 to 18 Oct 2009, nearly 98%

originated in the capital city.20 About 50% of Monrovias population lives in slums and

INGOs respond to cholera hotspots through the provision of communal latrines,

public tap stands and hygiene promotion.

This case study sought to answer:

1. Do communal latrines significantly reduce open defecation in Monrovias

slums?

2. Is the community management of communal latrines sustainable?

5. Materials and methods

The study was comprised of a desk-based review and field research in Monrovia. The

fieldwork portion took place over a five-week period from 27 June to 31 July 2011. Access to

the research site was made possible with support of the Liberia WASH Consortium, which

comprises five INGOs including Oxfam GB, Concern Liberia, Tearfund, Action Contre la

Faim and Solidarits International. Concern Liberia is the only INGO that has built communal

latrines in three of the nine Monrovian slums. The sites comprise Billimah, Zinc Kamp, and

New Kru Town. All three communities participated in some of the research activities.

Civil war dates: 1989-1996 and 1999-2003

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

12/36

12

Figure 1: Research sites and activities

5.1 Search strategy

Database searches of OvidSP, Eldis, and Ovid Medline were conducted that combined the

keywords shared latrine communal latrine or toilet or communal flush toilet or

sanitation block and sanitation or excreta management or CBO or fe#cal sludge

management or ULTS or CHC or demand or participation or MDG or open

defe#cation or hygiene or behavio#r change or technolog* and Africa and slum* or

informal settlemen or urbani#ation or urban area*. Searches were limited to English

language articles, and citation searching was conducted to identify additional references and

titles on the research topic.

5.2 Data collection tools

The case study employed qualitative and quantitative methods. The quantitative data was

analysed using Statistics/Data Analysis (STATA), while interviews were audio recorded and

coded with NVivo 8.

5.2.1 User counts

Delays in reaching the field prohibited enumerators from conducting a traditional user tally atthe Zinc Kamp site. Therefore the number of users was derived by dividing the cost-per-use

COMMUNITY VILLAGE POP BUILT HOURS MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES

Zinc Kamp

(pay-per-use)

2,362 24 hours WASH

Committee

Logan Town

Kinc Kamp

(Shared)

2,871

2010

6.00-22.00 WASH

Committee

HH survey

Transect walk

Individual/group

interview

Latrine

observation

New Kru

Town

(Beach)

LOCKED WASH

Committee

Freeport

New Kru

Town

3,783 2009

LOCKED WASH

Committee

HH survey

Transect walk

Individual

interview

Billimah I 6.00-22.00 WASH

Committee

Bushrod

Island

Billimah II

3,520 2010

6.00-22.00 WASH

Committee

HH survey pilot

Latrine

observation

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

13/36

13

(LD $5) by the sum of fees collected at the Zinc Kamp pay-per-use facility. On 7 July, the

day of the household survey, 20 users paid to use the Zinc Kamp facility. The monthly toilet

at Zinc Kamp has an average of 18 rooms (mean household size of 7.8), which means an

average of 140 have access to the pay-monthly facility. No information on the gender and

age of users was ascertainable from these data, and all rooms and users reportedly paid the

same established fees. No user count for New Kru Town was possible because the facilities

have been locked for nearly five months in a community political spat.

5.2.2 Latrine inspections

Visual inspections were conducted in Zinc Kamp and Billimah to ascertain the physical

conditions of the latrines and whether the latrines safely separated human excreta from

human contact. The survey assessed whether there were visible faeces in the cubicles, if

there materials for hand washing or anal cleansing, if a foul smell existed and whether the

facility was well maintained or needed repairs. At the Billimah facilities, the caretaker was not

on duty and two of the six cubicles were locked. At one of the Zinc Kamp facilities one of the

caretakers was not on duty and only a partial observation was possible. Observation of the

areas outside of latrines in New Kru Town revealed many instances of open defecation near

the facilities. [See Appendix 11.3]

5.2.3 Household survey

Six community-based enumerators were deployed to New Kru Town and Zinc Kamp slum

sites on 7 July 2011. Billimah was not included in the household survey because after

learning that New Kru Town community had no access to communal sanitation the survey

was used to measure variations in the defecation practices and attitudes toward communal

sanitation in the two intervention communities. The survey gathered data on household

composition, household resources, sanitation practices, communal latrine use and

frequency, satisfaction with the facilities, perceptions of established fees and prevalence of

self-reported diarrhoea. A comparison of the mean values between Zinc Kamp and New Kru

Town communities were done using simple group comparisons. Statically significant

differences were revealed in regards to defecation practices of adults, but no significant

differences were found between the defecation practices of children or the diarrhoea

prevalence in the households of both communities.

LD $5 equals US $0.07.

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

14/36

14

The enumerators were trained on 4-5 July and the survey was piloted in Billimah on 6 July.

Systematic data cleaning took place on 9 -10 July to eliminate errors that took place during

collection or data entry. [See Appendix 11.2]

5.2.4 Key informant interviews

Six key informant interviews were conducted with WASH Committee members and WASH

and programme mangers working at Liberia WASH Consortium partner agencies. Interview

topics covered topics including capacity building and training of WASH Committees,

monitoring activities and communal latrines as a response to cholera. The interviews were

audio recorded to increase the validity of the data. Coding took place with NVivo 8.

5.2.5 Group interview

A group discussion was conducted with the Logan Town Women s Development Association

on 11 July to ascertain the gender-and-child responsiveness of the communal latrines.

Questions included childrens use of the toilet, considerations of cost for childrens use,

womens safety and privacy. Due to security concerns, the group interview was not audio

recorded. Coding took place with NVivo 8.

5.2.6 Transect walks

Transect walks took place at Zinc Kamp and New Kru Town slums. On 1 July a transect

walk took place with the New Kru Town WASH Committee chairman. He revealed that the

toilet facilities had been locked for nearly five months in a community political spat. Near the

communal latrines there was nearly half a dozen piles of faeces covered with flies. The

WASH Committee Chairman then lead the team to an open defecation site on the beach,

about 100 metres away from beachside toilet facility. Groups of children were observed

defecating on the beach, and adults were observed going to-and-fro the site. The WASH

Committee chairman said that meetings were planned with the local administrator of the

slum to regain access to the latrines.

On 6 July a transect walk took place with the Zinc Kamp chairman. The walk started at the

pay-monthly facility and ended at the front of the settlement. He pointed out areas where

households were squatting on unpaved government roads and explained how this

prevented any potential sanitation upgrades for large portions of the community because no

tankers could access pits or septic tanks for emptying. The poorest households lived in this

The group interview took place outside.

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

15/36

15

area. He also pointed out the section where many people owned homes, and stated that

although some homeowners could afford to build household toilets, the tradition was often

that people built the house first and thought about the toilet later. He also pointed out

abandoned latrines and non-functioning tap stands due to poor design and people stealing

the metal taps to pawn for money. He cited access to water and sanitation as one of the

biggest issues in the community.

5.2.7 Ethical Considerations

The LSHTM Ethics Committee approved this study on 3 June 2011. An amendment to the

application was filed on 6 June 2011 to include the household survey as an additional

method.

5.3 Sampling

5.3.1 Selection of latrine facilities

Concern Liberia has built communal latrines in three slum communities in Monrovia:

Billimah, Zinc Kamp and New Kru Town. Each facility has two toilet blocks with six cubicles.

The user-latrine ratio is: 293:1 at the Billimah facilities; 393:1 at the Zinc Kamp pay-per-use;

478:1 at the Zinc Kamp monthly; and 315:1 at the New Kru Town facilities. All communal

latrines were observed either inside or outside for cleanliness and maintenance.

5.3.2 Selection of households

A near straight line from the latrine to 100 metres was taken with a Vonlen-511 etrex

handheld GPS. The sample was not adjusted for spatial clustering. Enumerators knocked on

every other house as a form of random selection of respondents. Interviewers then asked to

interview the head of the household, or a member of the household that was at least 18-

years old and had knowledge of the sanitation practices of the household. Information and

consent forms were completed before the interview took place.

5.3.3 Selection of key informant/group interviewees

As part of the collaboration with the Liberia WASH Consortium, WASH and Public Health

officers of Liberia WASH Consortium agencies were targeted for key informant interviews.

Concern Liberia WASH staff identified and called WASH Committee members from the

intervention communities to participate in the study. The chairman of Zinc Kamp community

contacted the chairwoman of the Logan Town Womens Development Association to

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

16/36

16

arrange the meeting with the women of the association.

6. Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums a case study

6.1 Introduction

Liberia is a West African country on the North Atlantic coast of Africa. It is bordered by

Guinea to the north, Cte d'Ivoire to the east, Sierra Leone to the northwest, and the Atlantic

Ocean to the south and southwest. The population is estimated at 3.6 million, about 48% of

which are urban inhabitants. Liberia was entrenched in two brutal civil wars over a 14-year

period from 1989 to 2003 (1989-1996 and 1999-2003). The conflict destroyed the nation s

infrastructure, institutions and systems of governance; uprooted families and killed an

estimated 250,000 Liberians. A direct result of the war is high levels of poverty in thecountry, with at least twothirds of the population surviving on less than US $1 per day.

About 99% of Liberians lack electricity and running water and access to sanitation is

severely limited.

Figure 2 Topographical map of Liberia21

6.2 National sanitation priorities

The Government of Liberia (GoL) has expressed its commitment to tackling poverty in its

poverty reduction strategy paper (PRSP) for 2008-2011. Sanitation and water are included

under Pillar IV, Infrastructure and basic services. The Governments goal vis--vis the PRS

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

17/36

17

is to reduce the water and sanitation-related disease burden through scaling up hygiene

promotion in communities and schools, and increasing access to clean water from 25% to

50% and increasing access to sanitation from 15% to 40% by 2011.

Figure 3 Sanitation coverage (%) in Liberia.Based on WHO/UNICEF JMP Statistics (2010)

6.3 Policy environment and institutional framework

Liberia passed its Water Supply and Sanitation Policy (WSSP) in 2009. In regards to urban

sanitation, the government aims to provide basic services for all through the provision of

piped sanitation or on-site sanitation systems.22 Funding to implement the WSSP has been

minimal and financing of the sector was a paltry 1% of the total budget in 2008/9. This

meager allocation took place even though Liberia signed the eThekwini Declaration on

Sanitation in 2010, in which African governments pledge a minimum commitment of 0.5% of

national GDP for sanitation and hygiene. The government has since increased its

commitment to WASH, and allocated sector ministries and agencies 7.3% of the total PRS

costs for 2010/2011.23 The 2010 United Nations Development Programme Country Status

Overview found that US $68 million would be needed annually to expand and sustain

sanitation in the country and only one-third of the necessary investment has been funded.24

Institutional arrangements

The roles and responsibilities for WASH are fragmented across three ministries and there is

no mechanism to lead or coordinate the overall strategy. As written, the Ministry of Land,

Mines and Energy (MLME) is in charge of water resources; the Ministry of Health and Social

Welfare (MoHSW) is responsible for water quality; the Ministry of Public Works (MPW)

provides water and sanitation to rural areas; the Liberia Water and Sewerage Company

(LWSC) is provides water and sanitation to populations over 5,000 urban areas (although

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

18/36

18

mandated for urban and rural). Donors and multi-lateral organisations have assumed a

budget support model where monies are contributed through one of several

reconstruction funds. INGOs have provided support and direction with the

implementation and scaling up WASH activities. It is not clear, however, from the

institutional arrangements exactly who has the responsibility for the oversight and regulation

of communal sanitation in urban areas.

6.4 Sanitation in urban MonroviaThe LWSC is responsible for providing water and sanitation services to Monrovia, the 15

County capitals, and other urban centres with populations greater than 5,000.An estimated

25% of Monrovia is connected to the sewer system, while 75% of the urban population uses

either on-site sanitation (pit latrines and septic tanks) or unimproved forms of excreta

disposal. There are no official figures on the number of people with flush toilets connected to

septic tanks, however, vacuum trucks empty the septic tank and drive outside of the city to

dump the contents into the sewer network. The contents are then released untreated into the

swamps and sea because of dilapidated sewerage network is not functioning.25

6.5 Sanitation provision in Monrovias slums

There are nine slum communities in Monrovia, most of which are located in flood prone

areas that pose significant sanitation related risks due to constant flooding and close

proximity to major refuse dump sites.The slums of Monrovia are vestiges of the war as a

majority of its inhabitants are internally displaced persons (IDPs). From 1980 to 2000, the

annual population increase in the capital city was 3.8% of unplanned growth. Monrovia s

population alone increased from 0.7 to 1.2 million people over the last 10 years of the

conflict and now stands at about 1.5 million. Slums began to form in the 1950s but slum

densification took place during and after the war. A 2011 Norwegian Refugee Council report

asserts that early on in the conflict, municipalities started charging yearly squatters rights

fees. This practice stems from a 1957 Zoning Code on non-conforming structures.

Charging squatters rights is a de facto practice that is broadly accepted but not clearly

legal. Paying the fee entitles the holder to occupy the area until such time as the

government fines [sic] it necessary to use the land in which case, one month notice will be

given to vacate the premises.26

While there is a dearth of information on sanitation in Monrovias slums, a 2009 Integrated

Regional Information Networks (IRIN) report found that in Clara Town, Monrovia nearly

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

19/36

19

75,000 people share 11 public toilets; and in West Point, Monrovia an estimated 70,000

people share four public toilets.27 Therefore, while communal sanitation is provided in slums,

access remains limited, and a high number of people are forced to defecate into plastic bags

and dispose of them as flying toilets or resort to open defecation.

With sanitation conditions such as these, diarrhoeal diseases are a major health concern in

Monrovia and in 2008 the WHO reported that 18% of all deaths in Liberia are WASH-

related.28 Cholera is endemic in Montserrado, Grand Basa, Grand Gedeh and Maryland

counties. Data from MoHSW reports 888 cumulative (suspected) cholera cases from 31 Dec

2008 to 18 Oct 2009. In River Cess County (2009) there were two reported cholera deaths.

The highest attack ratesor number of cases/populationoriginated in Bushrod Island

(0.02%), Sinkor (0.07%), Central Monrovia (0.10%) and West Point (0.21%). At least 47% of

randomly collected specimen (n=79) tested positive for vibriocholera serogroup 01 in the

lab.29

The INGO provision of communal latrines in Monrovias slums is one component of an

institutional response to cholera. Cholera hotspots or communities that dominate the

cholera reports*** have first priority in the INGO consideration of providing communal

latrines.30,31 Communal latrine provision is only one aspect of the cholera response. All

partners to the Liberia WASH Consortium implement other WASH activities in urban slums

including the construction of public tap stands, and hygiene promotion.

7. Results

7.1 Number of paying users

The number of users was calculated using financials made available from the Zinc Kamp

WASH Committee. The data was given for the number of months the latrines have beenoperational as it took nearly four months to find a caretaker and open the latrines for use.

The pay-monthly facility is located in a more isolated section of the community and the

WASH Committee converted it to a monthly payment scheme to make it financially viable.

While this fee structure has allowed the facility to operate, it has excluded those who are

unwilling or unable to pay the monthly fee, as it is accessible by key to members only.

***When there is a suspected cholera case, the General Community Health Volunteer (GHCV) reports the case to the

Environmental Health Team (EHT). The EHT then submits the report to the County Health Team (CHT), which is responsiblefor making the final report to the MoH. Cholera reports are also sent to the MoH when a person receives treatment at a

government clinic.

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

20/36

20

Pay-per-use facility

There are 2,362 people in the pay-per-use catchment area. For the month of July, the mean

number of paying users per day is 15, with a minimum of 11 users and a maximum of 26.

The mean number of users represents 6% of the target population. Calculations of users

from 6 February 2011 to 10 July 2011 found that the mean number of users per month is

353. This means that on average, only 15% of the target population is using the latrines per

month.

Pay-monthly facility

There are 2,871 people in the pay-monthly catchment area, and there are 18 rooms paying

each month to use the facility. Assuming that the average household size is 7.8, as reported

in the household survey, the pay-monthly facility serves an average of 140 users per month.

This represents about 3.2% of the target population.

Table 1: Number of facility users over one day

FACILITY EST POP32 TOTAL USERS33 % of total pop

Feb 330 Feb 14 %

Mar 437 Mar 19 %

Apr 376 Apr 16 %

May 354 May 15 %

Jun 460 Jun 19 %

Zinc Kamp I (Pay-per use) 2,362

10 Jul 162 July 7%

Zinc Kamp II (Monthly card) 2,871 140 users

7.2 Physical conditions and operating characteristics of facilitiesLatrine observations took place at Zinc Kamp and Billimah communities. The New Kru Town

facilities were locked but observation of the areas near the toilet block revealed many

instances of open defecation. The pay-monthly toilet block at Zinc Kamp is more similar to a

shared latrine and was much cleaner than the pay-per-use toilet block. Only one of the

caretakers was on duty during the site visits, therefore two of the latrines were locked.

Observation was therefore only possible on the unlocked cubicles.

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

21/36

21

Table 2: Operating characteristics of facilities

Of the total cubicles observable: 13% had faeces on the floor; 44% had faeces on the toilet

seat/slab; 25% had faeces on the wall; 25% had a foul smell; 75% had cobwebs; and 33%

were locked from the outside and there was no caretaker around with a key. The pay

monthly facility was cleaner than the pay-per-use facility at Zinc Kamp. All of the facilities in

Bilimah were pay-per-use and there no marked difference between the cleanliness of either

toilet block.

Table 3: Physical conditions of facilities

7.3 Social and economic characteristics of communal latrine users

The most common occupations of the head of household included caring for the family

(22%), casual work (21%) and informal business/petty trade (16%). The protracted civil

conflicts destroyed the economy and severely reduced livelihood options. Theinformal

sector is therefore a major provider of employment for the population. The informal sector

includes casual work, petty trade, construction, food/janitorial/security services and provides

some source of income for the officially unemployed.34

COMMUNITY Village POP BUILT HOURS MANAGEMENT

Zinc Kamp (Pay-per-use) 2,362 24 hours WASH CommitteeLogan Town

Kinc Kamp (Shared) 2,871

2010

6.00-22.00 WASH Committee

New Kru Town (Beach) LOCKED WASH CommitteeFreeportNew Kru Town

3,783 2009LOCKED WASH Committee

Billimah I 6.00-22.00 WASH CommitteeBushrod Island

Billimah II

3,520 2010

6.00-22.00 WASH Committee

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

22/36

22

Table 4: Ages and occupations of communal latrine users

Figure 4: Age distribution of respondents

7.4 Household latrine ownership

The mean household size is 7.8 (CI: 6,9). Of the 12 households reporting latrine ownership,

only 7 (58%) owned toilets that qualified as improved sanitation. The remaining 5 (42%)

owned hanging latrines, which do not safely dispose of human excreta. The two most

common reasons given for not having a household latrine is cost 43% (CI: 32, 54) and space

25% (CI: 16, 35).

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

23/36

23

7.5 Household resources

Households in the communities do not have a large resource base to draw from in terms of

assets or infrastructure. The average household does not own a refrigerator/icebox. Only

23% reported owning a generator and 22% reported owning a TV. The most common asset

that households owned was a mobile phone (62%). A woman heads the average household

and the main occupation for female-heads of households is homemaker and does not earn

an income. Families are large, on average about 7.8 household members, with only 65% of

head of households involved in income generating activities. Remittances account for some

of the resource base as 11% of respondents reported remittances as a form of support.

There was no association between household resources and reported communal latrine use.

7.6 Patterns of use reported by communal latrine users

Of the households interviewed for the household survey, 65% (CI: 54, 75) reported having

everused the communal latrines. All (100%) of Zinc Kamp users (n=28) reported that the

primary purpose for using the communal latrine was defecation, and 70% (CI: 52,89) of

users had used the latrines one day prior to the survey. Because the communal latrines at

New Kru Town have been inaccessible for nearly five months, the question of communal

latrine use was modified to investigate anyinstance of communal latrine use in the past. Of

those surveyed, 67% (CI: 51, 82) reported using the latrines at least once in the past.

While self-reported data show that communal latrines significantly affect open defecation in

Zinc Kamp, group interviews confirmed that promiscuous defecation is a big problem,

particularly at night. In the morning you walk outside and you see faeces all over the place.

You dont know who did it. You cant find the person, Ms. Jones exclaimed! Ms. Ellis

nodded in agreement. Its bad. If you see someone you tell them, this place is not for

you!35

Table 6: Communal latrine use

Facility Use (%) 95% CI

Zinc Kamp (n=39) 26 (67) (51, 82)

New Kru Town (n=40) 25 (63) (47,78)

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

24/36

24

Table 7: Frequency of communal latrine use

Zinc Kamp (n=39) Frequency

Once a day 18 (46)

Once a week 3 (8)

Twice per week 2 (5)More than three times per week 3 (8)

Dont use 13 (33)

7.7 Children and communal latrine use

At least 53 respondents reported that a child under five (U5) lived in the household.

Respondents reported that the usual place of defecation for U5s was the potty, 29% (CI:

19,39), bush, 20% (CI: 11,30), or beach 16% (CI: 8,25). While the use of a potty is hygienic,

the most common method of stool disposal is unhygienic. Of the total sample, 58% (CI:

47,70) reported that the faeces in the potty are customarily tossed in the drain/ditch, while

9% (CI: 3,15) reported disposing of the faeces with solid waste. Only 14% (CI: 6, 22)

reported throwing the stool down the toilet. Of these 26% (CI: 14, 39) reported that the U5

had experienced runny stomach (diarrhoea) within the past seven days. Upon entering the

yards to interview people, field workers observed scattered faeces near many of the houses.

Group discussions with women from the Logan Town Womens Development Association

revealed that WASH Committee members found that it was socially acceptable for childrento defecate in the open and that the cost to use the latrine was prohibited when it had to be

paid for multiple times for multiple children. Some of us have five or six children and we

dont have money to pay $5, $5, $5, $5 at the end of the day its [LD] $35. We need that

money to feed our children Ms. Jones said. Another woman added, The children are

supposed to go to the toilet but the money is too much, so they go in a small bucket but

sometimes outside near the house. Questions on what happens to the children s faeces in

the bucket were met with different answers. One woman said that mothers dig a hole and

cover it, but Ms. Morrison shook her head and said, We just let the children see to it.

Sometimes they throw it in a ditch.36 Findings suggest that cost and social acceptance of

children defecating in the open made it less likely for mothers to insist that children use the

communal latrines.

7.8 Payment and willingness-to-pay

Of communal latrine users, 37% (CI: 26,48) reported that the fee was too high while 25%

(CI: 16,35) thought that the fee was about right. A majority of respondents (46%) (CI: 15,

76) reported that they were willing-to-pay LD $5 for three uses, while 38% thought that a fair

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

25/36

25

price was LD $5 for 2 uses. Many of the public toilets in Monrovia charge "LD $5 for three

uses" and this recommendation is in line with the status quo. There was no separate fee

structure for children and the poorest community members.

Table 8: Established fees

Facility Fee

Zinc Kamp (pay-per-use) LD $5 per use

Zinc Kamp (monthly) LD $100 per month/per room

New Kru Town (I and II) LD $5 per use (closed)

Table 9: User perception of established fees (%)

Zinc Kamp & New Kru

Town

About right Too high Too low Dont use Dont know

Users (n=51) 14 (18)CI: 9,26

20 (25)CI: 16,35

1 (1)CI: -1,4

28 (35)CI: 25,46

16 (20)CI: 11,29

7.9 Sanitation access and plans for future use of communal latrines

The primary reasons for not having a household latrine were cost, 43% (CI: 32, 54), and

space 25% (CI: 16, 35). Plans for future use is high amongst the majority of respondents

57% (CI: 46, 69) with some variations between the two communities. Data reveal that more

users at Zinc Kamp do not expect to use the communal latrines compared to New Kru Town

residents. The difference could be attributable to access to sanitation, for example, New Kru

Town have no access whereas Zinc Kamp residents have some access and have expressed

dissatisfaction with cleanliness, cost and opening hours. More Zinc Kamp respondents plan

to build a latrine in the near future while no respondents in New Kru Town reported any such

plans.

Qualitative research revealed that aside from cost, land disputes prohibited latrine

construction. The majority (88%) of respondents in New Kru Town are from the Kru tribe,

and second to cost, lack of space, 38% (CI: 20, 50) was the second most common barrier to

latrine ownership. Transect walks through the community revealed physical space on the

plots; key informants revealed that lack of space referred to disagreements with

neighbours/kin on the location of septic tanks and to avoid disputes with ones neighbours/kin

many people would rather go without a toilet as this is traditionally how houses are built.

People build a house first, then they think about the toilet and at that time, it is too late,

there is no space.37

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

26/36

26

Table 10: Percentage of users who expect to use the latrines in the future

Facility Frequency (%) of users who do notexpect to be using the

facilities a year from now

Zinc Kamp (n=39) 26 (67)

New Kru Town (n=40) 8 (20)

Table 11: Percentage of users who plan to build a latrine in a years time

Facility Percentage of users who do notexpect to be using the

facilities in a years time and plan to build a latrine

Zinc Kamp (n=26) 7 (27)

New Kru Town (n=8) 0 (0)

7.9.1 Communal latrine users satisfaction with the facilitiesThe majority of currentcommunal latrine users (Zinc Kamp) reported being Satisfied or

Very satisfied with the provision of communal latrines. The top reason cited for liking the

communal latrines was privacy 36% (CI: 23, 48), and clean environment, 22% (CI: 11, 33).

The aspects of communal latrines that were not liked included cost, 42% (CI: 22, 63), night

closure of the facility, 27% (CI: 9, 45), and faeces on the toilet seat, 19% (CI: 3, 35).

Table 12: User satisfaction

Zinc Kamp (n=39) Frequency (%) 95% CI

Satisfied/V Satisfied 24 (62) (46,76)

Unsatisfied/V unsatisfied 2 (5) (-2, 12)

Dont use 13 (33) (18,49)

There were some differences in satisfaction according to gender. Women reported being

very satisfied 71% (CI: 51, 92) compared to 50%(CI: 25,75) of male respondents. Group

discussions with women found that they felt insecure when they had to defecate in the open

and that men sometimes stood and looked. Women said they preferred to use the communal

latrine or ask a neighbours toilet because open defecation is risky. You can be harmed at

any time, one woman said.38

8. Discussion

8.1: Do communal latrines significantly reduce open defecation in urban slums?

This small sample size allowed for the drawing of some general conclusions on the

effectiveness of communal latrines in reducing open defecation. In Zinc Kamp an average of155 people use the facilities each day and respondents reported that the facilities were used

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

27/36

27

primarily for defecation. Transect walks in Zinc Kamp and New Kru Town communities

revealed a higher level of faecal pollution in New Kru Town community, which has no

communal sanitation access at all. This observation provided further proof that communal

latrines do leadto less open defecation in the community but the manner and scale of

communal latrine provision does not stop open defecation.

At least 53 respondents reported that a child under five-years old (U5) lived in the

household. Most of the U5s defecated in a plastic bucket or outside. The fee structure and

the social acceptance of child open defecation influenced the decisions of mothers to allow

children to practice open defecation. Some mothers interviewed associated the childrens

runny stomach (diarrhoea) with poor sanitation, and at least 26% (CI: 14, 39) of the

respondents reported that an U5 in the household had experienced runny stomach within

the past seven days. A limitation of this association is that this study relied on self-reports of

diarrhoea prevalence and did not adjust for other factors. However, positive associations

between diarrhoea in children and unhygienic child defecation and faeces disposal practices

have been reported in 15 rigorous studies.39 These findings raise serious doubts on

communal latrine provision as an adequate response to cholera if the peri-domestic domain

is polluted with fecal matter that exposes and re-infects household members.

Concern Liberia does not have a child-friendly toilet design and the WASH Committee has

established a standard fee for all users. Children must often rely on adults to accompany

them to the latrines and pay the user fees. As a result, they are often left no choice but to

defecate in the open. This has adverse affects on their health, and organisations that provide

communal latrines should take steps to ensure target communities do not neglect the

sanitation needs of its most vulnerable members. Inclusiveness can be encouraged though a

progressive price structure and child-friendly designs that make it easy for mothers to bring

their children to use the communal latrines.

8.2: Is the community management of communal latrines sustainable?

There are two dominant forms of communal latrine management: Municipality-based and

community-based. This case study focuses on the community-based management of

communal latrines through the critical lens of sustainability. This is a necessary critique as

MDG Goal 7, Target 7c, aims to reduce by half, by 2015, the proportion of people without

sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation.40

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

28/36

28

The MDGs do not specify or conceptualise what is meant by sustainable sanitation, but

most definitions encompass technical, financial, environmental and social aspects. The

EcoSanRes criteria for sustainable sanitation reads: protecting and promoting human health;

not contributing to environmental degradation; and being technically and institutionally

appropriate, economically viable and socially acceptable.41 The sustainability criteria applied

to the communal latrines built by Concern Liberia encompasses the environmental, financial,

technical and community aspects of the EcoSanRes criteria.

Technical

Concern-built communal latrines are pour-flush toilets attached to septic tanks. The design

was chosen because many of the slums are located on sand and have high water tables.

The technology choice affects management if the community is unable to effectively respond

to problems on its own, with limited external assistance. The WASH committee members of

Zinc Kamp and New Kru Town have reported the incidence of tank overflow and discharge

of raw sewage into the environment (particularly during the rainy season). Users responded

by not using the latrines and complaining about the cleanliness of the toilets. It was also

reported that digging shallow wells and fetching water to flush the toilet was burdensome,

and this also had some influence on people using the communal latrines.

The topography of Liberia and the slum context make septic tanks an appropriate and a

problematic choice. With user fees as the only money available for the O&M of the latrines, it

can be difficult to raise enough money to empty the tanks, said Morris Sherman,

Construction Engineer for Concern Liberia.42 Emptying the tanks cost from USD$100 to US

$150, depending on the size of the community and tank. The communities tell us that the

cost is too much, Mr. Sherman said. The LWSC (LWSC) is responsible for emptying the

tanks, although the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) has assisted communities on

request at a charge of US $75. Large tanks require about three trips (US $100 per trip),

which is expensive for low-income communities to afford. The technical aspect of the

communal latrines has made it difficult for the target population to manage the provision of

communal latrines, as the complete sanitation cycle has not been well considered from the

birth of the project.

Financial

If the money raised from user fees is not enough to operate and maintain the toilets, the

tanks become full, the toilets smell and people will avoid using the facility. In the Monrovia

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

29/36

29

example, user fees are the only source of revenue for the O&M of the toilets. Community

sources report that the user fees will not cover the cost of de-sludging the tanks at the time

that they need servicing. Alternative financing mechanisms must be explored as 25% (CI:

16,35) of users said that the current fee is too high. Therefore, increasing the fee to meet

O&M costs could have an adverse affect on use. As the new Liberia WSSP emphasises pro-

poor policies, Concern Liberia could advocate with the LWSC to empty septic tanks in the

slums at a reduced rate. This could be an entry point for strategic partnerships with the local

government. The Umande Trust and the Greater Mumbai SSP have demonstrated ways to

achieve full cost-recovery without charging burdensome user fees. This model should be

explored for its transferability to the Monrovia context.

Community

When Concern Liberia builds a communal toilet it hands the facility over to the community for

use and upkeep. Community members serve on the WASH Committee, which comprises 10

members including: two Community Health Volunteers, community water pump mechanic, a

sanitation representative, and community leaders with influence. Concern Liberia

coordinates the capacity building and training of the committee through inviting partners to

give workshops on different aspects of O&M. Key informants revealed that motivation is of

Committee members is sometime low, and the lack of tangible incentives mean that

participation can be unsatisfactory.

The WASH Committee is solely responsible for the management of the latrines and

communal latrine provision has suffered in both communities because of management-

related issues. A dispute over the handling of funds led to the locking of the communal

latrines in New Kru Town for nearly five months. Self-reported defecation is quite high 92%

(CI: 84,100) and transect walks revealed a high prevalence of faecal contamination in the

environment, and an open defecation site that was only 100 metres away from the

beachside communal latrine. The WASH Committee chairman said that he would soon

schedule talks with the local authority about re-opening the latrines.

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

30/36

30

Figure 5: New Kru Town communal toilets that has been locked nearly five months in community dispute.

In Zinc Kamp the toilet block near the rear of the settlement was locked nearly four months

from the time it was built, because the WASH Committee couldnt find anyone to take the

role of caretaker. The WASH Committee wanted to base the caretaker salary as a

percentage of the user fees collected, but couldnt predict how much the facility would collect

without previous intake. Without a caretaker, there was no way to collect money and de-

sludge the toilet that would certainly fill with use. The toilets remained locked until the

Committee set up a monthly card allotted by the room.

The fee is LD $100 per room, and 18 rooms are currently paying for the monthly card that

gives them 24-hour key access. This has increased ownership of the facilities, but it has also

prohibited community members who do not participate in the scheme from using the now

semi-private toilets. Comparisons were made of the cleanliness of the pay-per-use toilet and

the pay-monthly toilet. The latter was cleaner the former and informal talks with users found

that they had a sense of ownership of the toilets.

In both cases the management issues were not reported to Concern Liberia, even though

directives are given to the Committees on when and how to report issues with the

management of the latrines. Key informants report that the reporting system is inadequate

because many people in the communities are related to one another and it becomes difficult

to make complaints. As this is a post-conflict setting with a relatively weak government,

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

31/36

31

people have also experienced making complaints to the local authorities with no results. It is

reported that many community members view making complaints as a waste of time.

Concern Liberias informal reporting/monitoring mechanism has therefore not been

responsive to realities in the community. Concern Liberia is piloting a Complaints Response

Mechanism (CRM) in target communities, which will provide participant populations with

ways to communicate problems with Concern Liberia and partners. This should assist with

the monitoring and support of community-managed communal latrines.

Environmental

The current design of Concern Liberia communal latrines is not environmentally sustainable

as emptying the septic tanks means that raw sewage must be emptied into the environment,

because the sewer network does not function properly. Although expansion of the sewerage

network is not the mandate of Concern Liberia, choosing sanitation technologies that do not

further degrade the environment is the responsibility of the organisation. Other technologies

such as composting toilets, for example, a double-vault VIP latrine (built up in case of high

water tables), or an Arborloo toilet.

Given the above findings and studies highlighted in the literature search, it would seem

sensible to conduct a qualitative study on the sanitation knowledge, attitudes and practices

of the target population to better inform the INGO response to sanitation provision in the

slums. This study was not able to assess the financial sustainability of the latrines but it

would be appropriate to thoroughly investigate the Umande Trust (Nairobi) and Greater

Mumbai Slum Sanitation Project for transferability to the Monrovia context.

8.3 Limitations of the study

The household survey was conducted with six community-based enumerators: three were

capable performers and three were not. None of the enumerators had previous survey

experience as specified in the agreement with the host organisation. This was partially

mitigated with practice gained from piloting the household surveys and an additional day of

training to allow more time for practice. If I were to repeat this study I would insist on

experienced enumerators and allow for a longer period of training in the chronogram.

All diarrhoea cases and sanitation behaviour relied on self-reports and were subject to

courtesy bias. The enumerators were not blinded to the research question and triangulation

revealed variations between the responses in the household survey and individual/group

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

32/36

32

interviews. Logistical restraints prevented the focus-group discussions with users and non-

users from taking place. This wouldve provided more in-depth analysis of user satisfaction

and insights into the management of the latrines.

Published information on WASH in Liberia is limited, as many of the ministries do not have

Internet access and the country. While the literature search was done in a systematic way, I

did not do a systematic review of communal sanitation provision in Africa slums. This would

have yielded mixed results as many African countries face the same limitations to

information provision as the ministries in Liberia.

Some information and methods included in the protocol were not included in the study. The

exit surveys were not included because transport to the survey sites was delayed and teams

arrived after the peak time to conduct interviews. This limited the ability to assess user

satisfaction and the extent that the latrines provide for the daily sanitation needs of the target

population. An examination of other-low cost technologies was excluded because it would

have made the focus of the study too broad.

9. Conclusions

The findings from this report are based on a small sample in the capital city of Liberia. More

research is needed to determine whether the findings are generalisable to other settings.

While some people in the target population are using the communal latrines, the manner and

scale that facilities have been provided is not sufficient to stop open defecation. There were

disparities in access within and across intervention communities, with children most often

excluded.

The health implications of the communal latrines inability to stop open defecation and

decrease cholera have severe consequences for child survival. Children in slums tend to

have poorer nutritional status and overall health and are highly susceptible to diarrhoea,

which kills nearly 1.5 million children U5 each year.43 Childrens faeces also have a higher

prevalence and intensity of intestinal worms and both stages of the transmission cycle (the

excretion of worm eggs, and the infection of the next host 44 frequently occur when children

stools lie on the ground, particularly in the yard. Communal latrine provision as a response to

cholera will not prevent the endemic presence of the bacteria because a majority of the

population does not use the facilities and hand-washing basins with soap are unavailable. 45

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

33/36

33

The level of communal latrine use and sustainability are inextricably linked. The findings

suggest that the community-management of communal latrines in Monrovian slums is not

sustainable under the current model. User fees have been barely enough to operate the

structures and alternative financing mechanisms have not been identified. Furthermore, the

absence of the caretakers during operational hours implies that not all users are paying the

fee. The capacity of the various WASH Committees is disparate and Concern Liberia has not

found a way to address the dearth of knowledge and skills in the community.

Sustainability also requires the engagement and participation of all stakeholders. The lock-

down of two communal latrines in New Kru Town is proof that not all actors have been

mobilised to value the importance of sanitation in the health and human rights of the

community and the WASH Committees do not have enough power to assert these rights.

While the technical design is responsive to the soil conditions, the septic tanks are not

environmentally friendly because the waste is being dumped untreated into the sea. While

water is abundant in Liberia, the absence of nearby water sources has proven burdensome

to those who must walk distances to fetch water to flush the toilet.

Communal latrines as a response to inadequate sanitation and cholera in Monrovia s slums

has major shortcomings that can only be mitigated through revising the management

structure of the latrines, ensuring that all factors for sustainability are systematically

addressed.

10. Recommendations

Findings from the study were presented to the Liberia WASH Consortium and stakeholders

at Oxfam GB Liberia on 29 July 2011 in Monrovia, Liberia. The recommendations are aimed

at Concern Liberia and Consortium partners.

The key recommendations are to:

Ensure that all communal latrines are built with hand-washing facilities with soap.

Advocate with municipalities for a reduced rate to empty septic tanks in slum

communities.

Create a demand for sanitation through well-planned hygiene promotion activities in slum

communities as part of the Concern Liberia WASH programme.

Explore low-cost ecological sanitation options composting toilets such as double-vault

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

34/36

34

VIP latrine (built up in case of high water tables) and/or Arborloo toilets.

Educate and build the capacity of WASH Committees through standardised trainings to

ensure a basic level of skills. Curricula should include trainings (and refresher trainings)

on handling complaints, responding to feedback, O&M requirements and bookkeeping.

Promote gender equity on the WASH Committees.

-

7/29/2019 Communal Latrine Provision in Liberian Slums

35/36

35

1 Progress on Sanitation and Drinking-Water 2010 Update. 2010. WHO/UNICEF JMP,Genenva.

2 Toubkiss, J 2008. Financing sanitation in sub-Saharan cities: a local challenge. IRCSymposium: Sanitation for the Urban Poor Partnerships and Governance Delft, TheNetherlands. IN: IRC Symposium: Sanitation for the Urban Poor Partnerships andGovernance, Delft, The Netherlands.

3 Uwejamomere, T 2008. Turning Slums Around: The case for water and sanitation.London: WaterAid.

4 "United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Urban Indicators Secure Tenure, Slums andGlobal Sample of Cities, 2002." Nairobi: UN Habitat, 21.

5

Cairncross, S 2004. The case for marketing sanitation. WSP-AF (Water and SanitationProgram for Africa) Field Notes, Nairobi, Kenya, digitally available at: http://www. wsp.org/publications/af_marketing. pdf.