1436_10591_1076121644_LESSON Standard RP Cockney Estuary English

Cockney dialect

Transcript of Cockney dialect

Региональная научно-практическая конференция

творческих работ учащихся «Перспективный проект»

26 апреля 2008 года

МОУ сош № 4 г. Дмитрова

Английский язык

«London English Dialect Cockney”

Выполнила: Дергачева Анастасия Анатольевна, 8 класс

Научный руководитель работы: Глушатова Ольга Сергеевна,

учитель английского языка

2008 г.

2

Table of Contents

page

Introduction………………………………………………………………….... 3

Chapter 1…………………………………………………………………….... 5

§1. Etymology of the Cockney dialect…………………………………. 5

§2. Cockney area……………………………………………………….. 7

§3. Cockney speech……………………………………………..……… 9

3.1 Typical features………………………….……………............. 10

Chapter 2…………………………………………………….…….………….. 12

§1. The origins of Cockney rhyming slang………….….………........... 12

§2. Rhyming slang in popular culture…………….……………............. 15

§3. Common examples…………………………….……………........... 19

Chapter 3…………………………….………………………………………... 20

§1. The future of the Cockney dialect………………………….……… 20

Conclusions………………………………………...……………….….……... 22

Bibliography…………………………………………………………….......... 24

3

Introduction

The term cockney has both geographical and linguistic associations.

Geographically and culturally, it often refers to working class Londoners,

particularly those in the East End. Linguistically, it refers to the form of English

spoken by this group.

For a long time the Cockney dialect was frowned upon by educated people

as uneducated and vulgar manner of speaking. The Cockneys were considered

stupid, poor and uneducated themselves (Bahr 1974: 108). That attitude towards

Cockney was until very recently when the acceptance of the dialect and its

speakers changed. What is a Cockney, though? A true Cockney has to have been

born within the sound of the Bow Bells of St. Mary-le-Bow Church in London’s

East End (Wells 1982: 302). Cockney is one of the most remarkable dialects all

over the English-speaking world. At the beginning of the 20th century there was the

decline of the dialect because of the non-existing acceptance in English society.

Cockney was mainly a working-class accent, but was also taken up by criminals

who enjoyed the population’s incapability to understand the accent and dialect. A

lot has changed since. Cockney had its ups and downs. It was on the rise in 90s,

been promoted by films like Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, Snatch, and

music by the Streets. When having a look at popular culture today, one might have

the impression that the dialect isn’t as popular as it was fifteen years ago.

Nowadays it’s being swept aside by new hip-hop inspired dialect.

The aim of this paper is to examine the development of Cockney dialect

through ages and its influence on the English that can really be heard in England.

To achieve our aim we should solve some problems:

to examine the quintessence of the Cockney dialect;

to analyze typical features of the Cockney dialect;

to research the popularity of the Cockney dialect in modern society.

This work consists of the Introduction, four chapters and the Summary.

4

In the introduction the decision to choose the subject is substantiate. The aim

and the problems are set.

The first section will be devoted to the etymology of word Cockney and its

area.

In the second section, the accent and dialect will be analyzed with regard to

its pronunciation and grammar.

The third part will be deal with Cockney Rhyming Slang – the form of slang

based on cockney dialect in which a word is referred to by another word or term

that rhymes with it.

In the fourth section there will be a short prognosis for the future of the

dialect.

In the summary, the results of this paper will be summarized.

5

Chapter I

§1. Etymology of the Cockney Dialect

The term was used to describe those born within earshot of the Bow Bells as

early as 1600, when Samuel Rowlands, in his satire The Letting of Humours Blood

in the Head-Vaine, referred to 'a Bowe-bell Cockney'. Traveller and writer Fynes

Moryson stated in his work An Itinerary that "Londoners, and all within the sound

of Bow Bells, are in reproach called Cockneys." John Minsheu (or Minshew) was

the first lexicographer to define the word in this sense, in his Ductor in Linguas

(1617), where he referred to 'A cockney or cockny, applied only to one born within

the sound of Bow bell, that is in the City of London'. However, the etymologies he

gave (from 'cock' and 'neigh', or from Latin incoctus, raw) were just guesses, and

the Oxford English Dictionary later authoritatively explained the term as

originating from cock and egg (Middle English 'cokeney' < 'coken' + 'ey', lit. cocks'

egg), meaning first a misshapen egg (1362), then a person ignorant of country

ways (1521), then the senses mentioned above.

Francis Grose's A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785) derives

the term from the following story:

A citizen of London, being in the country, and hearing a horse neigh,

exclaimed, Lord! how that horse laughs! A by-stander telling him that noise was

called Neighing, the next morning, when the cock crowed, the citizen to shew he

had not forgot what was told him, cried out, Do you hear how the Cock Neighs?

An alternative derivation of the word can be found in Webster's New

Universal Unabridged Dictionary: London was referred to by the Normans as the

"Land of Sugar Cake" (Old French: pais de cocaigne), an imaginary land of

idleness and luxury. A humorous appellation, the word "Cocaigne" referred to all

of London and its suburbs, and over time had a number of spellings: Cocagne,

Cockayne, and in Middle English, Cocknay and Cockney. The latter two spellings

could be used to refer to both pampered children, and residents of London, and to

6

pamper or spoil a child was 'to cocker' him. (See, for example, John Locke, "...that

most children's constitutions are either spoiled or at least harmed, by cockering and

tenderness." from Some Thoughts Concerning Education, 1693).

7

§2 Cockney Area

The region in which "Cockneys" reside has changed over time, and is no

longer the whole of London. As mentioned in the introduction, the traditional

definition is that in order to be a Cockney, one must have been born within earshot

of the Bow Bells. However, the church of St Mary-le-Bow was destroyed in 1666

by the Great Fire of London and rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren. After the bells

were destroyed again in 1941 in The Blitz of World War II, and before they were

replaced in 1961, there was a period when by this definition no 'Bow-bell'

Cockneys could be born. The use of such a literal definition produces other

problems, since the area around the church is no longer residential and the noise of

the area makes it unlikely that many people would be born within earshot of the

bells anymore [Wright 1980:11].

A study was carried by the city in 2000 to see how far the Bow Bells could

be heard, and it was estimated that the bells would have been heard six miles to the

east, five miles to the north, three miles to the south, and four miles to the west.

Thus while all East Enders are Cockneys, not all Cockneys are East Enders.

The traditional core neighbourhoods of the East End are Bethnal Green,

Whitechapel, Spitalfields, Stepney, Wapping, Limehouse, Poplar, Millwall,

Hackney, Shoreditch, Bow, and Mile End. The area gradually expanded to include

East Ham, Stratford, West Ham and Plaistow as more land was built upon.

Migration of Cockneys has also led to migration of the dialect. Ever since

the building of the Becontree housing estate, the Barking & Dagenham area has

spoken Cockney. As Chatham Dockyard expanded during the 18th century, large

numbers of workers were relocated from the dockland areas of London, bringing

with them a "Cockney" accent and vocabulary. Within a short period this famously

distinguished Chatham from the neighbouring areas, including the City of

Rochester, which had the traditional Kentish accent.

In Essex, towns that mostly grew up from post-war migration out of London

(e.g. Basildon, Harlow and West Horndon) often have a strong Cockney influence

on local speech. However, the early dialect researcher A.J. Ellis believed that

8

Cockney developed due to the influence of Essex dialect on London speech. [ Ellis

1890:35, 57, 58]

9

§3 Cockney Speech

Cockney speakers have a distinctive accent and dialect, and frequently use

Cockney rhyming slang. The Survey of English Dialects took a recording from a

long-time resident of Hackney.

John Camden Hotten, in his Slang Dictionary of 1859 makes reference to

"their use of a peculiar slang language" when describing the costermongers of

London's East End. In terms of other slang, there are also several borrowings from

Yiddish, including kosher (originally Hebrew, via Yiddish, meaning legitimate)

and shtumm (/ʃtʊm/ originally German, via Yiddish, meaning quiet), as well as

Romany, for example wonga (meaning money, from the Romany "wanga"

meaning coal), and cushty (from the Romany kushtipen, meaning good). A fake

Cockney accent, as used by some actors, is sometimes called 'Mockney'.

10

3.1. Typical features

H-dropping [Linguistics 110 Linguistic Analysis: Sentences &

Dialects, Lecture Number Twenty One — Regional English Dialects English

Dialects of the World]

Broad /ɑ:/ (in words such as bath, path, demand, etc), which

originated in London but has now spread across the south-east and into Received

Pronunciation. However, there are exceptions to this rule; for example, the word

maths, whose pronunciation often surprises people from the North or the South-

West.[Wright 1980:136-137]

T-glottalisation: Use of the glottal stop as an allophone of /t/ in

various positions, including after a stressed syllable [Sivertsen 1960:111], [Hughs &

Trudgill 1979:34]. /t/ may also be flapped intervocalically. [Sivertsen 1960:109]

Glottal stops also occur, albeit less frequently for /k/ and /p/, and

occasionally for mid-word consonants. For example, Richard Whiteing spelt

"Hyde Park" as Hy' Par' . Like and light can be homophones. "Clapham" can be

said as Cla'am. [Wright 1980:136-137]

Loss of dental fricatives: [Sivertsen 1960:124]

/θ/ becomes [f] in all environments. [mæfs] "maths"

/ð/ becomes [v] in all environments except word-initially when it is

[d]. [bɒvə] "bother," [dæɪ] "they." Very occasionally, this occurs mid-word, as

"Bethnall Green" can become Bednall Green. [Wright 1980: 137]

Diphthong alterations:

/eɪ/ → [æɪ]: [bæɪʔ] "bait" [Hughs & Trudgill 1979:39-41]

/əʊ/ → [æʉ]: [kʰæʉʔ] "coat"

/aɪ/ → [ɑɪ]: [bɑɪʔ] "bite"

/aʊ/ may be [æə]: [tʰæən] "town"

Other vowel differences include

11

/æ/ → [ɛ] or [ɛi] [t n] "tan" [Hughs & Trudgill 1979:35]

/ʌ/ → [ɐ]

/ɔː/ → /oː/ when in non-final position

/iː/ → [əi] [bəiʔ] "beet"

/u:/ → [əʉ] or [ʉ:] [bʉ:ʔ] "boot"

Vocalisation of dark l, hence [mɪowɔ:] for Millwall. The actual

realization of a vocalized /l/ is influenced by surrounding vowels and it may be

realized as [u], [o], or [ɤ]. [Matthews 1938:35]

Cockney has been occasionally described as replacing /r/ with /w/. For

example, thwee instead of three, fwasty instead of frosty. Peter Wright, a Survey of

English Dialects fieldworker, concluded that this was not a universal feature of

Cockneys but that it was more common to hear this in the London area than

anywhere else in Britain. [Matthews 1938:78]

As with many urban dialects, Cockney is non-rhotic. A final -er is

often pronounced as [ə]. Words such as car, far, park, etc. can have an open [ɑ:].

An unstressed final -ow is pronounced [ə]. This is common to most

traditional, Southern English dialects except for those in the West Country.

Grammatical features:

Use of me instead of my, for example, "At's me book you got 'ere ."

[Wright 1980:135]

Use of ain't instead of isn't, am not, are not, has not, and have not

Use of double negatives, for example "I didn't see nothing."

Most of the features mentioned above have, in recent years, partly spread

into more general south-eastern speech, giving the accent called Estuary English;

an Estuary speaker will use some but not all of the Cockney sounds.

12

Chapter 2

§1 Cockney Rhyming Slang

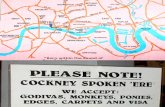

Traditional Cockney rhyming slang works by taking two words that are

related through a short phrase and using the first word to stand for a word that

rhymes with the second. For instance, the most popular of these rhyming slang

phrases used nationwide is probably "telling porkies" meaning lies as "pork pies"

rhymes with lies. Also "boat" meaning face as "boat race" rhymes with face.

Similarly "plates" meaning feet ("plates of meat"), and "bread" means money

(bread and honey). Americans sometimes repeat the word "raspberry," meaning a

bilabial trill, but don't know that it is taken from "raspberry tarts," which rhymes

with "farts." (This has been said to have been used by Victorian servants to conceal

their speech from their employers' ears.)

The origins of rhyming slang are disputed. It remains a matter of speculation

as to whether it was a linguistic accident or whether it was developed intentionally

to confuse non-locals. If deliberate, it might have simply been used to maintain a

sense of community; or to be used in the marketplace for vendors to talk amongst

themselves without customers knowing what they were saying; or it may have

been used by criminals (see thieves' cant) to confuse the police.

In recent years the practice of dropping the rhyming word and using just the

first word in the pair has become less common, as the slang has been used by

people who don't understand the traditional rules. The bastardized form, in which

the full phrase is used, is now assumed by many people to be Cockney rhyming

slang. In its original context this form makes no sense since it does little to exclude

outsiders. It was popularized by Cockney comedians for just that reason.

The proliferation of rhyming slang has meant many of its traditional

expressions have passed into common language, and the creation of new ones

(often ironically) is no longer restricted to Cockneys. Some substitutions have

become relatively widespread in Britain, such as "have a butcher's" (which means

to have a look, from "butcher's hook"), and these are often now used without

13

awareness of their origins. Many English speakers are unaware that the term "use

your loaf" is derived from "loaf of bread" meaning head. This also holds for

varieties of rhyming slang in other parts of the world: in the United States a

common slang expression, "brass tacks", may be a rhyme for "the facts" and; the

most common Australian slang term for an English person is "pommy", which is

believed to have originated as rhyming slang for immigrant.

Some words are much less taboo than their etymology would suggest.

However, many people would be horrified to learn that terms they use frequently,

like "berk" (often used to mean "foolish person") and "cobblers" (often used to

mean "what you just said is rubbish"), are actually from Berkeley Hunt, meaning

"cunt," and "cobbler's awls", meaning "balls".

The non-native speaker needs to be cautious in using rhyming slang to "fit

in". The extent of the use of the slang is often exaggerated; only a very few phrases

are in everyday use. Many examples are only used by people who are discussing

rhyming slang, or by people who are being ironic or are making up a term on the

spot for a joke, often at the expense of the tourist. In addition, since the original

purpose was to encode or disguise speech from the comprehension of bystanders,

terms that become too 'well-known' still have a tendency to lose actual currency

fairly quickly, putting whatever usage the slang enjoys into a constant flux.

This style of rhyming has spread through many English-speaking countries,

where the original phrases are supplemented by rhymes created to fit local needs.

Creation of rhyming slang has become a word game for people of many classes

and regions. The term 'Cockney' rhyming slang is generally applied to these

expansions to indicate the rhyming style; though arguably the term only applies to

phrases used in the East End of London. Similar formations do exist in other parts

of the United Kingdom; for example, in the East Midlands, the local accent has

formed "Derby Road", which rhymes with "cold": a conjunction that would not be

possible in any other dialect of the UK.

All slang is rooted in the era of its origin, and therefore some of the meaning

of its original etymology will be lost as time passes. In the 1980s for example,

14

"Kerry Packered" meant "knackered"; in the 1990s, "Veras" referred to Rizla

rolling papers ("Vera Lynns" = "skins" = Rizlas), as popularized in the song

"Ebeneezer Goode" by The Shamen; and in 2004, the term "Britneys" was used to

mean "beers" (or in Ireland to mean "queers") via the music artist "Britney Spears".

Cockney Rhyming Slang may have had its highs and lows but today it is in

use as never before.

In the last few years hundreds of brand new slang expressions have been

invented - many betraying their modern roots, eg "Emma Freuds: hemorrhoids";

(Emma Freud is a TV and radio broadcaster) and "Ayrton Senna": tenner (10

pound note).

Modern Cockney slang that is being developed today tends to only rhyme

words with the names of celebrities or famous people. There are very few new

Cockney slang expressions that do not follow this trend. The only one that has

gained much ground recently that bucks this trend is "Wind and Kite" meaning

"Web site".

15

1.1 Rhyming Slang in Popular Culture

The British comedy series Mind Your Language (1977) features a

character (caretaker Sid) who uses Cockney rhyming slang extensively. The show

also had a whole episode dedicated to Cockney rhyming slang.

Musical artists such as Audio Bullys, The Streets, and Chas & Dave

regularly use rhyming slang in their songs. The UK punk scene of the late 70s

brought along bands that glorified their working-class heritage: Sham 69 had a hit

song "The Cockney Kids are Innocent"; often audience members would chant the

words "If you're proud to be a Cockney, clap your hands" in between songs. The

term "Chas and Dave" is also rhyming slang for "shave". Ian Dury who used

rhyming slang throughout his career, even wrote a song for his solo debut New

Boots and Panties! entitled Blackmail Man, an anti-racist song that utilized

numerous derogatory rhyming slang for various ethnic minorities. The idiom even

briefly made an appearance in the UK-based DJ reggae music of the 80s, in the hit

"Cockney Translation" by Smiley Culture; this was followed a couple of years

later by Domenick & Peter Metro's "Cockney and Yardie".

Classic rock band Deep Purple used Cockney rhyming slang in the

title for the song "A Gypsy's Kiss", on their Perfect Strangers record: the title

actually means "A piss".

Rhyming slang is often used in feature films, such as Lock, Stock and

Two Smoking Barrels (1998) (the United States DVD version comes with a

glossary to assist the viewer), and on television (e.g. Minder, Only Fools and

Horses, EastEnders) to lend authenticity to an East End setting. In To Sir With

Love Sidney Poitier's students baffle him with their use of rhyming slang. Austin

Powers in Goldmember features a dialogue between Powers and his father Nigel

entirely in rhyming slang. The theme song to The Italian Job, composed by Quincy

Jones, contains many rhyming slang expressions; the lyrics by Don Black amused

and fascinated the composer.

16

The film Green Street Hooligans (2005) features a brief explanation

of the process by which rhyming slang is derived.

The box office success Ocean's Eleven (2001) contains a piece of

made-up rhyming slang, when a character uses "barney" to mean "trouble," and

derives it from Barney Rubble. (In actual usage "barney" does not mean trouble; it

means an argument or a fight, and is not understood to be rhyming slang at all.

Understanding British English, by Margaret E. Moore, Citadel Press, 1995, does

not list "Barney" in its "Rhyming Slang" section. Slang and Its Analogues, by J.S.

Farmer and W.E. Henley, 1890, says that "Barney", which can mean anything from

a "lark" to a "row", is of unknown origin, and was used in print as early as 1865.)

The film The Limey (1999) features Terrence Stamp as Wilson, a

Cockney man recently released from prison who spices his conversations with

rhyming slang:

Wilson: Can't be too careful nowadays, y'know? Lot of tea leaves about,

know what I mean?

Warehouse Foreman: Excuse me?

Wilson: "Tea leaves"... "thieves".

Wilson: Eddy... yeah, he's me new china.

Elaine: What?

Wilson: "China plate"... "mate".

Wilson: I'm gonna 'ave a butcher's round the house.

Ed Roel: Who you gonna butcher?

Wilson: "Butcher's hook"... "look".

In the film The Football Factory (2004) the character of Zebedee is

berated for his occasional use of "that fucking muggy rhyming slang" by Billy

Bright.

Anthony Burgess uses rhyming slang as a part of the fictitious

"Nadsat" dialect in his book A Clockwork Orange.

In the Discworld novel Going Postal, rhyming slang is parodied with

"Dimwell arrhythmic rhyming slang," which is like rhyming slang, but doesn't

17

rhyme. An example of this is a wig being a prune, as wig doesn't, possibly by a

complex set of unspoken rules, rhyme with "syrup of prunes." (In Britain a widely

used example of real rhyming slang is syrup = syrup of fig(s) = wig).

In the film Mr. Lucky (1943), Cary Grant's character teaches rhyming

slang to his female companion. However the character describes this as Australian

rhyming slang.

On September 19, 2006, the comic strip Get Fuzzy introduced a new

character: Mac Manc McManx, a Manx cat and cousin of Bucky Katt. McManx

uses a speech pattern heavily based around Cockney rhyming slang and other

London slang, despite being from Manchester. These speech patterns often make it

almost impossible for the other characters, especially Satchel, to understand him.

The title character in the China Miéville novel King Rat (1998 novel)

uses Cockney rhyming slang in the vast majority of his dialog.

Ronnie Barker wrote a classic sketch for the comedy series "The Two

Ronnies" in which a vicar delivers an entire sermon in rhyming slang, a large

portion of which refers to a "small brown Richard the Third", which seems to mean

turd, until he says that it flew back to its nest.

Cockney rhyming slang is occasionally featured as a category on

Jeopardy!.

The Irish series of books and columns Ross O'Carroll-Kelly frequently

uses variations on rhyming slang popular (or allegedly so) among members of the

Dublin 4 population (for example, "battle cruiser" = "boozer").

The Disney movie One Hundred and One Dalmatians features some

Cockney rhyming slang by the two puppy thieves. Note that the rhyming word is

also included, for example "A lovely pair of turtle doves".

In Garth Ennis' The Boys, Billy Butcher refers to Americans as

Septics, then explains "Septic Tank: Yank"

On the London Weekend Television situation comedy from the 70's,

No, Honestly, air-headed character Clara referred to one woman "with the big

Birminghams." Her romantic partner, C.D., incredulous, asked her what she meant,

18

not recognizing a valid rhyming slang reference (Birmingham City = Titty). Clara's

explanation was, "Oh, C.D., it's rhyming slang - Birmingham town bosoms!"

which, of course, neither rhymes nor is slang.

In the new series of Doctor Who, in episode one of the 2nd season,

"New Earth", originally broadcast on April 15, 2006, Cassandra (who is

'inhabiting' Rose's body) asks Chip how Rose speaks. He replies, "Old earth

Cockney." She then uses several examples of Cockney rhyming slang, including

"I'm proceeding up the apples and pears" (stairs) and "I just don't Adam and Eve it"

(believe it)

Sex Pistol Steve Jones, on his Indie 103.1 radio program Jonesy's

Jukebox, refers to advertising breaks as "visiting the Duke." (Duke of Kent = pay

the rent.)

19

1.2 Common Examples of the Cockney Rhyming Slang

The rhyming slang is shown in blue and the meaning – in red:

Adam and Eve Believe Would you Adam and Eve it?

Alligator Later See you later alligator.

Apples and Pears Stairs Get up those apples to bed!

Army and Navy Gravy Pass the army, will you?

Bacon and Eggs Legs She has such long bacons.

Barnet Fair Hair I'm going to have my barnet cut.

Bees and Honey Money Hand over the bees.

Biscuits and Cheese Knees Ooh! What knobbly biscuits!

Bull and Cow Row We don't have to have a bull about it.

Butcher's Hook Look I had a butchers at it through the window.

Cobbler's Awls Balls You're talking cobblers!

Crust of Bread Head Use your crust, lad.

Daffadown Dilly Silly She's a bit daffy.

Hampton Wick Prick You're getting on my wick!

Khyber Pass Arse Stick that up your Khyber.

Loaf of Bread Head Think about it; use your loaf.

Mince Pies Eyes What beautiful minces.

Oxford Scholar Dollar Could you lend me an Oxford?

Pen and Ink Stink Pooh! It pens a bit in here.

Rabbit and Pork Talk I don't know what she's rabbiting about.

Raspberry Tart Fart I can smell a raspberry.

Scarpa Flow Go Scarpa! The police are coming!

Trouble and Strife Wife The trouble's been shopping again.

Uncle Bert Shirt I'm ironing my Uncle.

Weasel and Stoat Coat Where's my weasel?

20

Chapter 3

§1 The Future of the Cockney Dialect

Say goodbye to Eliza Doolittle and say hello to Ali G.

Today, you're more likely to hear about someone's "blud" - friend - or

"headin' westside" - going home - in London's East End rather than a reference to

having a "butcher's hook" - having a look - or "being someone's china plate" -

mate.

Cockney took root in the Victorian era as the unofficial phonetic twang of

everyday London, largely defined in popular culture by Dick Van Dyke’s Cockney

chimney sweep in "Mary Poppins" and Eliza Doolittle, the down-and-out London

flower girl in George Bernard Shaw's famed play, "Pygmalion".

But nowadays a new multicultural dialect, shaped by second-and third-

generation London immigrants, including West Africans, Afro-Caribbeans and

Bangladeshis is appearing.

"In postwar London, you saw a lot of migration out of the city by white,

working-class families into suburbs like Essex and satellite towns," said Sue Fox, a

research assistant in the Linguistics Department at London University's Queen

Mary College.

"Now, you have African, South American and Asian families blending all of

those old influences from cockney and their native languages together into a new

variety of speech."

A new mix of cockney and Bangladeshi has developed which is similar to

Received Pronunciation, particularly in vowel sounds, according to Sue Fox, a

research fellow in sociolinguistic variation at Queen Mary College, University of

London.

Researchers found that a new type of speech, influenced by a dizzying

number of foreign languages and pronunciations, rap music and popular TV

programmes have altered traditional cockney.

21

Among the most prominent television programmes is "Da Ali G Show," a

British Channel 4 show - also screened on HBO in the US - which features a hip

hop-obsessed Briton, Ali G, speaking in Jafaican tongue, decked out in colourful

jump suits and gold jewellery.

But English linguists are not so pessimistic about the future of the Cockney

dialect. Professor David Crystal, a BBC Voices consultant and one of the world's

leading language specialists, said that traditional cockney is not so much dying out

but that new kinds of mixed accents are developing.

"Walk down Brick Lane and you will hear all sorts of interesting voices and

dialects. Undoubtedly, some of the old-style cockney might be dying out as some

rural dialects are dying out. But all accents change."

The cockney accent is not disappearing altogether, but shifting to outlying

towns and boroughs, according to Laura Wright, senior lecturer in English

Language at the University of Cambridge.

"Long-standing East End communities were very much disrupted after the

second world war, partly due to bomb damage, partly to slum clearance, and many

inhabitants were transferred out of London to the newly built new towns, such as

Basildon and Harlow," Dr Wright said.

"Of course, when East Enders resettled they took their speech with them.

They and their descendants continue to speak in an east London dialect with east

London accents - although this has changed over the intervening half century, as

language is continually changing. Such speakers today would not sound identical

to their East End antecedents."

22

Conclusions

The cockney dialect is an English dialect spoken in the East End of London,

although the area in which it is spoken has shrunk considerably. It is typically

associated with working class citizens of London, who were called cockneys, and

it contains several distinctive traits that are known to many English speakers, as the

dialect is rather famous.

The term ―cockney‖ comes from a Middle English word, cokenei, which

means ―city dweller.‖ It is probably derived from a medieval term referring to the

runt of a litter or clutch of eggs, which was used pejoratively to refer to people

living in the then crowded, disease ridden, and dirty cities. The distinctive accent

of working class Londoners, especially those living in the East End, was remarked

upon by observers as long ago as the 17th century.

The primary characteristics of cockney dialect include the dropping of the

letter ―H‖ from many words, the use of double negatives, contractions, and vowel

shifts which drastically change the way words sound. In addition, many consonants

or combinations are replaced with other sounds, as is the case in ―frushes‖ for

―thrushes.‖ In some cases, the final consonant of a word is also dropped, for

example ―ova‖ for ―over.‖ Many of the traits of cockney speech suggest the lower

classes to some observers; for example, the use of ―me‖ to replace ―my‖ in many

sentences is usually associated with a less than perfect understanding of the

English language.

One of the more unique aspects of cockney speech is cockney rhyming

slang. Although rhyming slang is not used as extensively as some fanciful

individuals might imagine, aspects of it are certainly used in daily speech. In

cockney rhyming slang, a word is replaced with a phrase, usually containing a

word which rhymes with the original word, for example ―dog and bone‖ for

―telephone.‖ Often, a word from the phrase is used as shorthand to refer to the

23

initial word, as is the case with ―porkies‖ for ―lies,‖ derived from the rhyming

slang ―porkies and pies.‖

Cockney speech can be extremely difficult to understand, especially for

other English-speaking people, as it is littered with word replacements thanks to

rhyming slang, cultural references, and shifts in vowels and consonants which can

render words incomprehensible to the listener. Like other unique dialects, a thick

cockney accent can seem almost like another language. Care should also be taken

when attempting to mimic it, as the cockney dialect can be very slippery,

especially when it comes to the use of rhyming slang, and native users may be

confused or amused by the attempts of a non-native.

Some linguist have become concerned that the cockney dialect may fall out

of spoken English, due to the influence of multicultural immigrants in London who

have added their own regional slang and speech patterns to the dialect. Others

believe that the cockney dialect will never die, vice versa it is regenerating.

24

Bibliography

1. Ellis, Alexander J. (1890), English dialects: Their Sounds and Homes

2. Hughes, Arthur & Peter Trudgill (1979), written at Baltimore, English

Accents and Dialects: An Introduction to Social and Regional Varities of

British English, University Park Press

3. Matthews, William (1938), written at Detroit, Cockney, Past and Present: a

Short History of the Dialect of London, Gale Research Company

4. Sivertsen, Eva (1960), written at Oslo, Cockney Phonology, University of

Oslo

5. Wright, Peter (1981), written at London, Cockney Dialect and Slang, B.T.

Batsford Ltd.

6. Ayto, John. 2002. The Oxford Dictionary of Rhyming Slang. Oxford

University Press.

7. Franklyn, Julian. 1960. A Dictionary of Rhyming Slang. Routledge.

8. Green, Jonathon. 2000. Cassell's Rhyming Slang. Cassell.

9. Lillo, Antonio (full name, Antonio Lillo Buades). 1996. "Drinking and

Drug-Addiction Terms in Rhyming Slang". In Comments on Etymology 25

(6): pp. 1-23.

10. Lillo, Antonio. 1998. "Origin of Cockney Slang Dicky Dirt". In Comments

on Etymology 27 (8): pp. 16-20.

11. Lillo, Antonio. 1999. "More on Sausage and Mash 'Cash'". In Gerald L.

Cohen and Barry Popik (eds.), Studies in Slang. Part VI. Peter Lang, pp. 87-

89.

12. Lillo, Antonio. 2000. "Bees, Nelsons, and Sterling Denominations: A Brief

Look at Cockney Slang and Coinage". In Journal of English Linguistics 28

(2): pp. 145-172.

13. Lillo, Antonio. 2001. "The Rhyming Slang of the Junkie". In English Today

17 (2): pp. 39-45.

25

14. Lillo, Antonio. 2001. "From Alsatian Dog to Wooden Shoe: Linguistic

Xenophobia in Rhyming Slang". In English Studies 82 (4): pp. 336-348.

15. Lillo, Antonio. 2004. "A Wee Keek at Scottish Rhyming Slang". In Scottish

Language 23: pp. 93-115.

16. Lillo, Antonio. 2004. "Exploring Rhyming Slang in Ireland". In English

World-Wide 25 (2): pp. 273-285.

17. Lillo, Antonio. 2006. "Cut-down Puns". In English Today 22 (1): pp. 36-44.