City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

-

Upload

city-limits-new-york -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

0

Transcript of City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

1/28

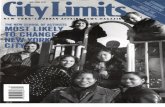

D ec em b er 1 99 1 N ew Y ork 's C omm un ity A ffa irs N ew s M a ga zin e

C L O S IN G C O M M U N IT Y C L IN IC S 0 L O W IN C O M E C A R E E R L A D D E R SH O M E L E S S O R G A N IZ A T IO N S W O R K IN G

Damaged DreamsThe Failure of Community Control

at Taino Towers

$2.5

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

2/28

CitJl Limi tsVolume XVI Number 10

City Limits is published ten times per year,monthly except bi-monthly issues in June/July and August/September, by the City LimitsCommunity Information Service, Inc., a nonprofit organization devoted to disseminatinginformation concerning neighborboodrevi alization.SponsorsAssociation for Neighborhood andHousing Development, Inc.Community Service Society of New YorkNew York Urban CoalitionPratt Institute Center for Community an dEnvironmental DevelopmentUrban Homesteading Assistance BoardBoard of DirectorsEddie Bautista, NYLPIICharter RightsProjectBeverly Cheuvront, NYC Department of

EmploymentMary Martinez, Montefiore HospitalRebecca Reich , Turf CompaniesAndrew Reicher, UHABTom Robbins, JournalistJay Small , ANHDWalter Stafford, New York UniversityPete Williams, Center for Law andSocial JusticeAffiliatians for identification only.

Subscription rates are: for individuals andcommunity groups, $2010ne Year, $301TwoYears; for businesses, foundations , banks,government agencies an d libraries, $35/0neYear, $501Two Years. Low income, unemployed, $1010ne Year.City Limits welcomes comments and articlecontributions. Please include a stamped, selfaddressed envelope for return manuscripts.Material in City Limits does not necessarilyreflect the opinion of the sponsoring organizations. Send correspondence to: CITY LIMITS,40 Prince St. , New York, NY 10012.

Second class postage paidNew York, NY 10001City Limits (ISSN 0199-0330)(212) 925-98 20FAX (212) 966-3407Editor: Lisa GlazerSenior Editor: Andrew WhiteContributing Editors: Mary Keefe,Peter Marcuse, Margaret MittelbachEditorial Intern: Paula KalakowskiProduction: Chip CliffePhotographers: Isa Brito, Ricky Flores,Andrew Lichtenstein , Franklin KearneyAdvertising Representative: Jane Latour(212) 304-8324Copyright 1991. All Rights Reserved. Noportion or portions of this journal may bereprinted without the express permission ofthe publishers .City Limits is indexed in the Alternative PressIndex and the Avery Index to ArchitecturalPeriodicals and is available on microfilm fromUniversityMicrofilms International,Ann Arbor,MI48106 .

2/DECEMBER 1991jCnv UMITS

ANew Era

Wth little fanfare, President George Bush recently approved a$23.9 billion spending package for the National AffordableHousing Act. His penstroke reverses the federal government's

withdrawal from the housing field-and signifies a historicstep forward for community-based housing groups.The overall spending figure is only a slight increase from las t year, buthe creation of new housing programs is what makes the difference. Thelargest new part ofthe package is HOME, which provides $1.5 billion foa patchwork quilt of housing efforts. A significant portion of the HOMEmoney-$225 million-is set aside for local, nonprofit housing providers.Like the city of New York, the federal government is finally starting torecognize the worth and abilities of these groups. It's a welcome shiftand long overdue. But as this month's cover story shows, it's vital forthese groups to stay true to their community roots and their responsibilities.At Taino Towers, the community-based ownership group has betrayedits activist past and slipped into complacency, allowing the developmento deteriorate so much that a federal housing inspector noted, "Theseconditions are unacceptable and must change if Taino Towers is evegoing to become a decent place to live."Any time an effort at community control falters, it provides ammunition for people in power who resent supporting projects run by locafolks. It's important that Taino Towers be seen as the exception rathethan the rule, and that community-based groups work doubly hard toensure long-term accountability within their organizations. 0

Cover photograph by Franklin Kearney.

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

3/28

1 I I ' ~ f j ' j t l FEATUREDamaged DreamsTaino Towers was meant to be a showcase for commu-nity control-but it's fallen under the sway of a singleman. 10DEPARTMENTSEditorialANew Era ... .... .. ................... .... .............. .................. 2BriefsScreening Lawsuit .................. .............. ..... ............. 4Divided SRO ........ ... ..... .............. ....................... ...... 4Bronx Reinvestment ............ ...... ........... ..... ............. 5ProfileVoices From the Streets .................. ............ ............ 6Pipeline

Closing Down the Clinics ........ .............. ...... ...... .. .. . 8Climbing the Job Ladder ........................................16Vital StatisticsToil and Trouble:Low income employment during the recession ... 18CityviewWhy Doesn't She Just Leave? ...... .......... ........ ........ 20Letters ........................................................................ 22ReviewThe NIMBY Manual .......................................... ..... 24

Clinics/Page 8

Dreams/Page 10

Job Ladder/Page 16

CITY UMITS/DECEMBER 1991/3

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

4/28

11:1;'1"11SCREENINGLAWSUIT

A recent court decision shedsa ray of sunlight on the screening committees that tenantassociations and communitybased management groups useto pick and choose tenants fortheir city-owned buildings.In the ruling, Justice PhyllisGangel-Jacob of the stateSupreme Court states that thecity's guidelines for screeningcommittees are too informal.The decision, in Johnson vs . Cityof New York, requires the city'sDepartment of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD)to issue written criteria outliningexactly who is eligible for anapartment in Tenant InterimLease (TIL) buildings - city

owned buildings managed bytheir own tenants' associations.Gangel-Jacob also rules thatprospective tenants be informedin writing of the tenant selectioncriteria, and that anyonerefused an apartment receive awritten explanation for thedenial.Advocates for the homelessand Legal Aid attorneys say thejudge's decision sets a precedent and should be followed inall city housing programs wherecommunity groups rent outapartments.Kristin Morse of the Coalitionfor the Homeless says that thecity's lack of strict governmentguidelines for the screeningcommittees encourages all kindsof abuse, from delays in rentalto blatant discrimination .placement workers in theshelters speak of men rejectedbecause screening committeessuspect HIV infection, womenrejected because they have alive-in lover, or others rejectedbecause their relatives or formerspauses are suspected ofinvolvement with drugs.But Deputy CommissionerWilliam Spiller of HPD deniesthat discrimination is an issue."If people have complaints, theyshould bring them to us," hesays. liTo my knowledge, ithasn't happened ." In midNovember the city appealedJustice Gangel-Jacob's decision .While the case is beingappealed, the city does not haveto issue the tenant selectionguidelines. Still, the Legal Aid4/DECEMBER 1991/CITY UMITS

Society lawyer that argued theJohnson case, Beatrice Dohrn,says the city is morally bound tofix the system. "If the city doesnot propase standardizedguidelines there's going to bearbitrary enforcement," shesays. The committees "have tobe told the bosic rules: you haveto treat each applicant exactlythe same way."

In the Johnson case, thejudge did not rule that discrimination had taken place. AlvisJohnson, the plaintiff, appliedfor an apartment in 41 ConventAvenue, a TIL building whereshe already lived with hermother. She was rejectedseveral times. A member of thetenants' screening committee,G. Drummond Samuels, admitsthat Johnson was never given awritten explanation for herrejection. But she denies thatJohnson was rejected simplybecause she was a singlewoman on welfare, as theplaintiff charged.

In her decision, the judgesays that because she is unableto discern whether or notdiscrimination took place, thetenant selection system does notmeet the requirements of civilrights law.While advocates for thehomeless are eager to see thecity issue guidelines, membersof many tenants associationsand community-based housingmanagers take the oppositeview. Samuels argues that the

city should have no involvementin screening. "You ought to beabl e to keep control of who youlive with," she says. "I don't goalong with them making youtake someane who you know isno damn good."Susan Cole of the SettlementHousing Fund, which provideshousing for homeless families,agrees. "I don' t want HPD'sguidelines," she says. "Somefamilies can't be housed. Whatdo I do when one family in-fringes on the rights of all theothers?" D Andrew White

DIVIDED SROIn a move that may pit a

public television station againstlow-income tenants, Channel13-WNET is pressing the city toallow the conversion of a Roorin a Manhattan single-roomoccupancy hotel from residentialto commercial use.Channel 13, which alreadyoccupies the first nine Roors inthe 23-Roor Henry HudsonHotel at 353 West 57th Street,was nearly through its tenthfloor renovation last monthwhen it was slapped with astop-work order. At issue iswhether the station, which isexpanding its production space,harassed any tenants in thebuilding. The Roor has beenvacant for almost two years .

Work on the $600,000project cannot resume until thecity's Department of HousingPreservation and Development(HPD) approves the station'srequest for a certificate of nonharassment. As City Limits goesto press, the agency says it willrule soon on whether to orderan administrative hearing on thmatter.The television station, whichhas a long-term lease andoption to buy the 10th Roor, isnot the only non-profit in theHudson . St. Luke's-RooseveltMedical Center leases spacefor employee housing andoffices-on floors 1 1 through23 from owner Irving Schatz.The non-f)rofits' activitieshave raised fears of displacement among many of the hotel'20 0 residents, who live in rentcontrolled and some rentstabilized apartment on theupper Roors. With help from theWest Side SRO Law Project,about 70 residents met recentlyto form a tenants' union. Ten-ants, who include many elderly,are "genuinely scared now,"says Owen Lamb, the union'spresident.Larry Wood from the SROLaw Project says the situationhighlighted a potential conflictbetween a non-profit's objectives and the interests of low-income tenants. "Theirprograms are unrelated to theinterests of the peaple in thebuilding," he says. "You're

Families in the NYC Shelter Systemand Where They StayNumber of families ineach type of shelter, 10191: Private Rooms 3,166D Donnitories 464 Hotels 943lliill Other 223Total Families: 4,796

10/89 4/90 10/90 4/91 10/91Source: NYC Human Resources Administration.

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

5/28

really pitting one set of tenants-the non-profits-againstanother set of poor tenants."An HPD spokespersondeclined to discuss details ofChannel 13 's request. BertKnaus, Assistant Director of theMayor's Office on Homelessnessand SRO's, would not commentdirecrly on the case.H. Melvin Ming, the station'sChief Financial and Administrative Officer, denies that thestation harassed tenants or haddesigns on other Roors . "Ourconcern is that we don 't displace anyone," he says. 'W ewould not like to see ourselvesportrayed as promoting goodcitizenship and then not doingwhat we're preaching."Still, the tenants are fearful.Lamb says he and other tenantsare worried that St. Luke'sRoosevelt, which he says hadremoved washing machines anddryers and created lounges thatare off limits to tenants, wouldexpand their presence in thebuilding. But PhXllis Goodman,a spokesperson for Roosevelt,denies that the medical centerplans to expand or that it hasoffered to relocate residents offthe 11 th floor, as several tenantsclaim.Whether or not the hospitalexpands its presence in thebuilding, Wood thinks theprecedent of non-profits takingover SRO space is a dangerousone . St. Luke's-Roosevelt receives large amounts of fundingfor its outpatient programs fromthe city, he says. Yet, at thesame time, the government hasexpressed its intent to preserveas much SRO housing aspossible. He poses the questionthat lies beneath the surface ofthe conRict: "Do we want ourtax money to take away SROunits?" 0 Peter Howell

BRONXREINVESTMENT

While the rest of the nation'seconomy foltered in 1991, theFederal Home Loan MortgageCorporation, or Freddie Mac,managed to Rourish. Thecorporation and its sister in thehousing business, Fannie Mae,are quasi-public corporations

Foul Stench: Orundun Johnson , a resident of 62 6 Riverside Drive, joins a November 13th protest calling forthe closure of the city's North River Sewage Treatment Plant at a public meeting in Harlem. Neighbors ofthe plant call it a health threat and say the smell is unbearable .

chartered by Congress tofinance mortages, and the pairexpect to show combinedearnings nearing $2 billion forthe year.But the profitable FreddieMac has long been the target ofvehement calls for reform. Andnow, more than a year after thecorporation stopped financingmortgages for multi-familybuildings, one group in theBronx is demanding thatFreddie Mac make amends forpast errors by reinvesting itsvast resources in the borough'sforeclosed apartment buildings."Freddie Mac continues toabuse our neighborhoods," saysPhyllis Longworth of the Northwest Bronx Community andClergy Coalition (NWBCCq."And it's i m ~ r t a n t to hold themaccountable for it."The 17-year-old NWBCCC,which has helped rehabilitatemore than 5,400 housing unitsin Bronx neighborhoods, has foryears issued warnings ofproblems with Freddie Mac (seeCity Limits, June/July, 1990and March, 1989). Three yearsago the coalition accuratelypredicted that, if left unchecked,Freddie Mac's over-valuation ofproperty would lead to rampantspeculation, overfinancedbuildings, and, eventually, aspate of foreclosures. Afier thecorporation had invested morethan $740 million in secondarymortgages for hundreds ofapartment buildings in the

Bronx, the coalition's predictionscame true.About half of Freddie Mac'slosses in recent years resultedfrom defaults on apartmentbuildings-known bxmortgagers as multi-familyproperties-although sud;properties make up only aboutthree percent of thecorporation's portfolio. So lastyear Freddie Mac officialsdecided ta stop investing inmultifamily properties, leavingmost of the Bronx without accessto the federal loans.This October, Congress'General Accovnting Officeissued a report condemningFreddie Mac for its "weakcontrols" and overfinancing ofmultifamily properties. Now, theNWBCCC is calling for Congressional hearings and somesort of oversight that wouldforce Freddie Mac to return tothe borough and act responsibi t. Essentially, the coalition'sAffordable NeighborhoodsCommittee is calling on thecorporation to invest in buildin,gs in receivership and supportefforts toward tenant andcommunity ownership of properties. Following the Octobersale of a building to a landlordwho seffied a fraud lawsuit outof court with the city's housingdepartment five years ago, thecoalition also called for a freezeon sales of all Freddie Macproperties, so that tenants canscreen potential buyers.

So far, Freddie Mac isunmoved. According to aFreddie Mac spokesperson, thecorporation "will only get backinto the [multifamily mortgage)business when they're ready,and not one minute before."There are currenrly twoFreddie Mac buildings in theBronx (out of a dozen proposedby NWBCCq moving towardtenant ownership. According toFreddie Mac, financing has notbeen arranged for either properf)', and Phyllis Longsworth,NWBCCC chairwoman, saysthat Freddie Mac is "draggingits feet on this matter."What can be done to repairthe system? According to AllenFishbein of the Center lor Community Change in Washington,"the federal government couldpretty well decide how muchmoney Freddie Mac has toinvest in a given housing area,"dictating the portfolio mix ofFreddie Mac's investments. Arepresentative of the NWBCCCpoints out that "gov-ernmentcan call on FredClie Mac to bemore responsible, while it canalso regulate the industry."For the moment the situationremains confrontational. 'W ehave nothing to gain but decentand affordable places to live,"says Longworth. 'W e don'twant FreCldie Mac to leave, andleave dirty work behind for us toclean up. We want them torectify the problems." 0Steven Seltz .. .n

CITY UMITS/DECEMBER 1991/5

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

6/28

By Samme Chittum

Voices From the StreetsA group of homeless activists are setting their sightson the upcoming political conventions.

I t was a blustery fall evening, andJames Gibbs ha d taken the subwayfrom a downtown Manhattan parkwhere he lives to stand behind asmall podium in the modern auditorium at Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx."Right now I'ma homeless person," said Gibbs, amiddle-aged ma ndressed in darkpants an d wearinga quilted vest overa plain dark shirt.

Young concedes that the ambitiousplan, fraught with numerous obstaclesto success, may seem "abstract" tome n like Gibbs, who worried out loudabout the shabby appearanc.e of theclothes he was wearing, the only ones

powerment. Unable to command thresources of service-oriented groupthat dispense everything from sandwiches to psychiatric help, HOWwants to build a political agenda thaenables homeless people to speak fothemselves. Put simply, HOW wantto offer direction an d ideas instead oa doughnut, and an opportunity to bheard instead of being told."It [HOW] gives homeless peoplechance to really be involved in thprocess," says Steve Riley, a HOWmember an d president of the UniteHomeless Organization, a self-helgroup run byhomeless men anwomen. "It's verimportant thapeople who live inthe streets andshelters havevoice," says Rileya veteran of various shelters whnow lives in thBronx.To do thatHOWmust combaperceptions of thhomeless as help

"The homelesspeople in thestreets should beorganizing and gettogether," saidGibbs in a strongvoice easily heardby some 60 people,including shelterresidents, advocates for the homeless and a fewothers who came tothe conferencefrom the city'sstreets, parks an dshantytowns.

z less, says Youngwho also direct15 Parents on th Move, a group tha:J was formed to rep

resent residents o15 the Brooklyn Arm..........' - - - - - - - - - ~ : : ; : Hotel, wher

"The only thingI'd like to say is,Wortdng Together. Alberta Hines and Jean Chappell of Parents on the Move speak at the Young lived witNovember 8th HOW organizing meeting. her children afte

'Give us a chance and don't look downon us. You'd be surprised at howmany talented people there are outthere.'"Among those listening was RuthYoung, a veteran of the city sheltersystem and chairwoman of a ne w organizing group that wants me n likeGibbs to be heard loud and clear by alarger audience. The group is calledHomeless Organizations Working, orHOW. And one of its first goals is tosend homeless people like Gibbs tothe upcoming national political conventions as delegates .The conference that Gibbs attendedwas organized by HOW as a startingpoint on a long and difficult journeyto the Democratic National Convention to be held in Madison SquareGarden here in July, an d possibly theRepublican National Convention inHouston in August.a/DECEMBER 1991/CITY UMITS

he owns. But she an d a group of otheradvocates an d formerly homelesspeople say the plan is feasible an dimportant.Young explains that she hopes toget funding to provide a stipend forhomeless people to collect signaturesto become delegates. "I see this as aself worth kind of thing . .! see it ascreating jobs and uplifting them toanother state where they can say, 'I amsomebody. I am part of this,'" shesays.Direction Instead of a DoughnutThe decision to try to send theirown to the conventions is a clear statement about what HOW hopes toachieve. A grassroots ensemble ofhomeless people, veterans of homelessness and advocates for the homeless, HOW's leaders see th e neworganization as a vehicle for self-em-

they were evictefrom their home. "People think of uas poor misfortunates who they havto guide, that we can't think for ourselves. That's not the way it is."Swept Off the StreetsIt is not surprising that HOW'members, including an active core o12 who attend weekly meetings at thIndependent Support Center in StAgnes Church on 44th Street, chosthe convention as their first organizing target.In the past, the arrival of a convention has been a signal for cities to pusthe homeless out ofsight. That's whahappened in New York in 1980 whethe last Democratic National Convention came to town. "Homeless peoplwere literally swept off the street andinto the river," says Julie Kempner, member of HOW and until recentlstaff attorney for the Coalition for th

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

7/28

Homeless. "We don 't want that tohappen again."Faced with immediate practicalneeds-such as the lack of a computerand office space-HOW is nonetheless moving forward. Progress hasbeen made with a maximum of effortand a minimum of practical support.For instance, HOW would have likedto have hired a bus to carry peoplefrom the shelters to its conference,butthe organizers had to sett le for puttingup flyers instead.Young, who works out of he r cityowned apartment in the Tremontsection of the Bronx, has flung all ofher formidable energies into gettingHOW off the ground. She has beenattending meetings at a frantic pace,slowing down only when familymembers remind her to safeguard herhealth by taking a day off-insuranceagainst a relapse of illnesses related toLupus , a disease affecting the immunesystem, which almost cost Young herlife, and which she must contend withdaily.HOW 's next order of business,Young says, is applying for grants forthe project and organizing a two-dayworkshop during which committeeswill begin the task of selectingpotential delegates an d putting themto work for a candidate. Even Young,who seems to propel the organizationforward with her strength and vision,seems overwhelmed at times. "It'shard when you don 't have sophisticated equipment or salaries or a placeto do your organizing," she says."People don 't take you seriously."Byzantine SystemThe people HOW needs to reachare politica l players, e lected officials,party officers and candidates. HOWmust also wend its way through thedelegate selection process itself, aByzantine system accessible mainlyto party officers an d elected officials.The delegate selection processdiffers from party to party an d state tostate. In New York, registeredDemocrats who want to be one ofthestate's allotted 268 delegates from its34 congressional districts can chooseone of two paths to Madison SquareGarden. Those who are not competingfor the 10 9 seats reserved during thestate's party convention in May mustwork hard to get to the nationalconvention by gathering 1 ,000signatures door-to-door during a 30-day marathon from January 15 toFebruary 13 .

Can HOW succeed? At least onepresidential campaign organizationhas declared it needs people on thecampaign trail in New York, particularly in the boroughs. "If someone ina situation like that can gather 1,000signatures, they have more stick-to-

HOW wants tobuild a political

agenda thatenables homelesspeople to speakfor themselves.

itness than I do," says Jeff Myhre, alead organizer for the Jerry Browncampaign. "They are welcome. Myonly requirement is that they promisethat when it comes time to vote, theyvote for Brown."Myhre suggests that HOW couldsave some wear and tear by goingthrough the State DemocraticCommittee and asking the party tolook at approving HOW -sponsoredhomeless people as alternative delegates at the convention in May. Thatmethod, says Myhre, does 'not denyany party regulars a seat and vote atthe convention, but would get the

HOW delegates on the floor with credentials. "They can talk to Dan Ratheror anyone else," he says. "If hey makeit to the convention, the reporters willfind them. "Negotiationswith Democratic partyofficials are underway, says HOWmemberJohn Mensing. "Theyhaven'tsaid yes and they haven't said no. "To achieve its goals, HOW mustprove it can live up to its name bymustering support from othergrassroots groups. HOW has so farassembled a diverse membership,including representatives from Parents on the Move, Homegrown, Inc.,which helps homeless people withwelfare entitlements, and the Unionof City Tenants, which fights for betterhousing in city-owned buildings. Allwere represented at the recent HOWconference as was the Homeless CivilRights Project, a Boston organizationthat is run by homeless people whohave been successfully organizingagainst police brutality an d for accessto public places.HOW's aims are less immediatethan those set by the Boston group.Butthey'reequallyvital,saysMensing,emphasizing that the organizingprocess before the convention is asessential as the end result. "We'retaking a lot of people who are shut outof the process and putting them intothe middle of it ," he says. "We'retaking them from zero to 60 andputtingthem into the biggest politicall?rocessin the country . . here 's everything togain an d nothing to lose." 0Formerlya reporterat the Daily News,Samme Chittum now works as afreelance writer.

SUPPORT SERVICES FOR NONPROFIT ORGANIZATIONSWriting 0 Reports 0 Proposals 0 Newsletters 0 Manuals 0 ProgramDescription and Justification 0 Procedures 0 Training MaterialsResearch and Evaluation 0 Needs Assessment 0 Project Monitoring andDocumentation 0 Census/Demographics 0 Project and PerformanceEvaluationPlanning and Development 0 Projects and Organizations 0 Budgetso Management 0 Procedures and SystemsCall or write Sue Fox

710 WEST END AVENUENEW YORK, N.Y. 10025(212) 222-9946

CITY UMrTSIDECEMBER 1991/7

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

8/28

l I a ' a j " ~ ' I I By Paula Kalakowski and Andrew WhiteClosing Down the ClinicsCity government pulls the plug on free communitybased family planning for uninsured women.Kth lee n Maldonado doesn'thave much cash to spare. The26-year-old divorced mother oftwo from Staten Island is a fulltime computer-science student withno medical insurance, and sh estruggles to provide for her familywith her former husband's child support payments.Maldonado and thousands of otheryoung Staten Island women used togo to a clinic on the north shore ofStaten Island for free gynecologicalexams and family planning services,including no-cost birth control pills,condoms, diaphragms, and preventive diagnostic tests like pap smearsand breast exams. But the clinic onStuyvesantPlace in St. George, run bythe Community Family PlanningCouncil (CFPC), closed last June because of city budget cuts. Now, withno extra money an d little extra time,Maldonado has to turn to expensivepr ivate doctors or the local hospitalwith hours-long waiting times andsubstantial fees.

an d uninsured women, she says.The near-elimination of the CFPCcontract has left only eight of thegroup's clinics operating. Until thissummer, CFPC's clinics were the only

detected much later. More womenwill die."Advocates point out that the longterm consequences of he closings wilbe costly for the city. "If they takeaway access to preventive care, to thetreatment of minor health problemsthen we just wait until they becomemajor health problems," says JudyGallagher, executive director of theBronx Perinatal Consortium. "Thenwe're looking at a $5,000 or $10,000hospital bill that Medicaid will haveto pay."

The clinic was one of four community-based CFPC centers in the citythat shut their doors for good thissummer after th e Dinkinsadministration's Human ResourcesAdministration (HRA) chopped morethan two-thirds of the money, or $2.5million, from the organization'S citycontract. The cuts left a gigantic gap inthe health care services available tothe city's working poor and undocumented immigrant women, critics say,and killed a unique service that usedprimarily federal money to providefree preventive an d primary medicalcare.

No Access: Kathleen Maldonado stands outside the shuttered CFPC clinic in Staten Island.

Cutting Preventive Care"Even before the budget cuts, theaccess to gynecological care was drastically below what it needs to be, "says Stephanie Stevens, executivedirector of the W omen's Health Education Project. "In general, gynecological care has bottomed out." Theclinics' closings sent a shudderthrough the small network of healthcare organizations that provide neighborhood-based services to low-incomea/DECEMBER 1991/CITY UMITS

places in the city, outside the hospitalemergency room, where women whodon't qualify for Medicaid couldreceive free gynecological care. Now,only teenagers can get free care andbirth control services at CFPC clinics .Everyone else has to pay a fee basedon their income. The cheapest fee fora basic examination is $30. An d thefees for birth control materials beginat $5 and go up from there.That means uninsured, low-incomeworking women and undocumentedaliens living an d working illegally inNew York cannot get basic gynecological care unless they can affordto pay for it. "The working poor aretotally screwed," says Lisa Napoli ofthe Lower East Side Women's Center.Elsa A. Rios of the Committee forHispanic Children and Familiesagrees. "It's a great loss," she says."More women who need pap smearswon't get them. More women withcervical and breast cancer will be

City officials argue that the clinicwill not collapse if he city withdrawsfunding. Pat Maloney of the Mayor'Office for Children and Families sayCFPC can make up its budget gap inpart by treating more women who areeligible for Medicaid. Gallaghecharges that that's beside the point"We have people who are not eligiblfor Medicaid who will not have accesto health care," she says. "That's theproblem that has to be addressed, nothe financial tap-dancing of anyoneorganization trying to cover a gap intheir funding."And Ana Dumois, executivedirector of CFPC, agrees. "Thesedecisions were made under tremendous pressure," she says. "We'll haveto see less working poor."Sorry to See I t EndUntil the budget cuts, New YorkCity's free gynecological care founinsured women was a progressive

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

9/28

and unique achievement. For the pastten years, the city's social servicesagency has channeled federal grantmoney to CFPC. Other cities and townsacross the state that receive the sametype of grant money use it to distribute information about birth control orto refer women to clinics and physicians, says Bob Walsh of the state'sBureau of Reproduct ive Services. ButNew York City went much further,actually funding the free clinics. "Itwas very forward looking of the city,"he says. "We're sorry to see that end."A dozen or more governmentsubsidized free family planning clinicssprouted in New York City during theheyday of the War on Poverty in the1960s and early 1970s. But by the endof the 1970s , the clinics werefloundering because of governmentcutbacks, says Maloney of he Mayor'sOffice for Children an d Families.Planned Parenthood attempted to keepthem afloat bu t couldn't, she says,and the Koch administration, alongwith family planning advocates,decided the city should channel itsmoney to a single organization insteadof the numerous individual clinics.The umbrella organization thatemerged from the negotiations wasthe CFPC.The city looks to CFPC for morethan family planning and basic healthcare. Four years ago, the organizationcreated a city-funded mobile clinic toprovide prenatal care for pregnanthomeless women at two shelters inBrooklyn. The mobile clinic will notbe affected by the budget cuts. Inaddition, CFPC recently won a $1.2million grant from the Ryan WhiteFoundation to ru n a two-year comprehensive care an d monitoring programin East New York for carriers of theAIDS-causing HIV virus.The CFPC's contract for Fiscal Year1991, which ended last June, was for$3,544,000. Almost $3.2 million ofthat was federal grant money that wasfunnelled to CFPC via HRA. The restwas evenly divided between the stateand city funds. For every five dollarsthe city kicked into the program, thefederal government matched it with$90, says Lois Baron, a staff associateat CFPC.But last winter the city withdrewabout one-third of the $3.5 milliondollar contract, Baron says .Then, afterintense lobbying by advocacy groupslike the National Organization forWomen and the National AbortionRights Action League, and vocal sup-

port from members of he City Counciland Manhattan Borough PresidentRuth Messinger, the Dinkins administration stopped short of cutting thecontract altogether. The final decision:the city agreed to a $1 million contractfor the current fiscal year, now almosthalf over. Funding for the next fiscalyear remains unclear.City officials were not happy aboutmaking the cut. "CFPCisinvaluable,"Maloney says. "They should beexpanded, not cut." But the budgetcrisis left no other option, she says ."The so-called optional serviceshave to go in tough times like these,"says Nancy Martinez, director ofpolicy an d planning at the New YorkState Department of Social Services.Her agency is responsible for sendingfederal money to the city's HRA, whichthen channels it, in some cases, togroups like CFPC. She says the samefederal grants that used to be allocatedto CFPC are also used for programs thecity is required by law to provide,mainly protective an d preventiveservices for children in child abusecases, and for other programs like daycare. When government budgets ha dto be pared down, the city reduced itsshare o f funding for those programsan d used CFPC's federal money to fillthe hole.They Don't Have the Money

At the CFPC clinic on LudlowStreet on the Lower East Side, threemiddle aged Chinese women si t in thewaiting room and watch George Bushgive a speech about the new civilrights bill on television. They are notenthusiastic about Bush, and they arenot happy about theirne w clinic. Theyused to be patients at the CFPC clinicin Chinatown, but it closed thissummer. "It's no t comfortable here,"says Miss Tse, a 35-year-old who worksin a sewing factory and has no insurance. "In Chinatown, the staff was allChinese. There was a sense ofcommunity." And, she says, it will behard to pay the fee.Carmen Rodriguez sits behind adesk in the next room. She is theclinic's intake worker, processingpaperwork and keeping track ofpatient's files. "Sometimes I feel sosorry to tell patients they have to pay,"she says. "Sometimes they cry, sometimes they get mad at me. They don'thave the money."The women in the waiting roomsay they don't think this clinic can beconsidered "optional." Nor do the

women in Central Harlem, CrownHeights, an d Jamaica who have to puttogether the cash to afford an appointment at CFPC. "More an d more ofthesewomen are single heads ofhouseholds," says Elsa Rios. "The deterioration of their health leads to the deterioration of their function as mothers.That means we're talking about thedeterioration of the community ." 0Paula Kolakowski is a student at theNew School and an intern at CityLimits.

Community CareThe Community FamilyPlanning Council's eight clinicsprovide basic gynecological careand birth control services for afee based on income. Anyoneunder age 20 or on Medicaiddoesn't have to pay. The clinicsare:Community League Clinic1984 Amsterdam Avenue(at 159th Street)HarlemCFPC Health Center92-94 Ludlow StreetLower East SideWomen's Clinic910 East 172nd StreetThe BronxCFPC Health Center97-04 Sutphin BoulevardJamaica, QueensCABS Clinic94 Manhattan AvenueWilliamsburgCaribbean House Clinic1167 Nostrand AvenueCrown HeightsUnited Parents Center999 Blake AvenueEast New YorkSouth Brooklyn Clinic141 Nevins StreetBoerum HillFor further information call theCFPC at (212) 924-1400.

CITY UMITS/DECEMBER 1991/9

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

10/28

Damaged DreamsThe glass-and-concrete towers were meant to be a showcasefor community control. Today they're a scary place to live.BY LISA GLAZER

Oa clear day, the 35-story peaks of the TainoTowers can be seen from almost any point in EastHarlem. Rising above weedy, junk-strewn lotsand squalid tenements, the glass and concrete

towers were constructed as an island of dignityamid the decay of the barrio.The towers are home to more than 600 tenants an d arethe en d result of a grand experiment from the War onPoverty era. The premise: the ghetto could be overcome i fgovernment supported high-quality housing and socialservices for the poor. The original plans for the development included roomy apartments with terraces, a healthclinic, on-site day care, a school, a greenhouse, a community theater, a gymnasium and an Olympic-sized pool.After a well-publicized construction process thatlurched forward from 1972 to 1984, all this was built. Butthe real achievement went beyond bricks and mortar.Taino Towers received one of the largest subsidies in the10/DECEMBER 1991/CITY UMITS

history of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD}-and the owners were communitresidents.The ownership group is known as the East Harlem PiloBlock Housing Development Fund and the original boarof directors included community activists anconstruction workers. They aimed to transform no t onltheir block-Second an d Third Avenues between 122nan d 123rd Street-but the surrounding neighborhood awell.Nearly 20 years after the project broke ground, TainTowers has transformed the East Harlem skyline-buthat's about it. At ground level, conditions are bleak. Therwere 208 drug arrests this year on the single block wherthe towers stand, an d the development has more than 20current housing code violations. Inside Taino Towers, thelevators break down incessantly, stranding wheelchairbound seniors in their high rise apartments.Glass windoware shattered, stairways smell of urine, walls are coverewith graffiti. And the four-story day care center, th

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

11/28

gymnasium and theswimming pool sitempty, almost entirelydestroyed by vandalism an d neglect."They were suchbeautiful buildings.But now .. it's unbelievable," says JuanitaReyes, a communityaide for Councilmember Carolyn Maloney,wh o called for improvements at thedevelopment in the1980s. "It was supposed to be a model forEast Harlem but itturned out to be a nightmare."

l Betty Screenmoved into herduplex apartment in TowerThree of the TainoTowers in 1984. Afterlife in a cramped WestSide tenement, the spacious, three-bedroomli ving space was everything the Board ofEducation employee hadhoped for. And theview-i t was amazing.But itwasn't long before problems startedto emerge. Despiteplentiful warmth inmost of the apartment,Screen's bedroomdidn't receive heat soshe ha d to sleep in theliving room. There

Taino Towers is many flights of stairs. room and one year theThe demise of Hal of Shame: Elevators break down constantly so tenants have to walk down were leaks in the bath-no one individ- plumbing systemual's fault. It's easy to point the finger at glitches in erupted, destroying an expensive carpet and sofa.construction an d design, an d there's little doubt that "It makes you want to leave," says Screen, adding thatwaning support and limited oversight from the federal the only way she can receive timely repairs is by withholdgovernment has had a negative impact. But ultimately, ingherrentandtakingtheownerstocourt.Andeventhenresponsibility lies with the community owners and the repairs are poorly done. "I have to fuss after them all themanagement company they hired in 1986, Marvin Gold time."Management Incorporated. The ownershipgroup no longer Screen's experience is not unusual among residentialmeets regularly and has fallen under the sway of a single and commercial tenants at Taino Towers. In randomman. And the managers admit they have failed until interviews in the laundry room, hallways and apartments,recently to pursue one of the most standard procedures disenchantment is an oft-repeated theme. Stephenrequired at HUD-subsidized projects, undermining the Adolphus, the dean of Touro College, which is located inproject's income an d its upkeep. Taino Towers, has sent more than 100 letters of complaintThe story of Taino Towers could be dismissed as just to the management office about problems with heating, airone more sad saga from the Great Society era--except that conditioning and security, to little avail. And a youngNew York City's 10-year, $4.8 bill ion hous ing plan commits woman waiting impatiently for the single working elevaenormous subsidies to community-based,nonprofitgroups tor in Tower One says, "I remember going into labor. Thefor the development an d management of city-owned elevators weren't working so I was stranded. My brothershousing. And the federal government' s National Affordable ha d to carry me down 22 flights of stairs!"Housing Act sets aside funds specifically for local, The conditions described by these tenants are the resultnonprofit developers. While the government's growing of serious problems in the management and maintenancereliance on these community groups is a testament to their of Taino Towers that are spelled out in documents andincreasing sophistica tion and ability, Taino Towers serves information compiled by City Limits.as a harsh reminder of what needs to be done to assure that HUD reviews of Marvin Gold Management in 1990community-based owners live up to their name an d their and 1991 led to a "below average" rating for both years.responsibilities. According to the 1991 review, the maintenance log book

"We've grown very fixated on development," says at Taino Towers shows "a consistent pattern of delay orLarry Yates, a staff member at the National Low Income non-response."Housing Coalition, based in Washington, D.C. "It's pretty A physical inspection report from HUD noted thatclear that setting up a structure-no matter how good it there were 25 areas in need of urgent maintenance, includis-and leaving it alone just doesn't work. There has to be ing the roofs, the security systems an d the elevators. Thecontinuing involvement in the community. It's tough. inspector noted: "These conditions are unacceptable andYou fight hard to build abuilding, but in alot of ways that's must change if Taino is ever going to become a decentwhen the fight is just beginning." place to live.""Community control has to be an ongoing process," Taino Towers is $625,000 behind in water taxadds Emily Achtenberg, a national expert on subsidized payments, according to Joe Dunn, a spokesperson from thehousing and non-profit ownership groups. "The lesson city's Department of Finance. Because of unpaid taxes, thehere is that you can't take anything for granted. You have city started to take control of Taino Towers in 1989, but ato be vigilant to ensure that there is accountability at payment schedule was eventually reached. That agree-community-controlled organizations." ment is now in default, according to Dunn.CITY UMITSIDECEMBER 1991/11

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

12/28

Benjamin Flores is the man at the helm of the EastHarlem Pilot Block group, which owns Taino Towers an d is responsible for the maintenance andoperation of the complex. He blames most of theproblems at the development on an insufficient rentalsubsidy from the federal government, which failed tocover operating costs.Five years ago, Flores and hi s board hired Marvin GoldManagement to oversee day-to-day operations at TainoTowers for a fee of about half a million dollars per year.Based in Brooklyn, the company runs 260,000 units ofhousing across the city-a mixture of luxury housing,middle-income apartmentsand subsidized developments.Marvin Gold repeats Flores' charge, explaining that theproblems at Taino Towers are the result of rent levels toolow to keep up with operating costs.HUD provides all the tenants in the building with afederal Section 8 housing subsidy. Under this program,tenants pay a portion of the rent and HUD covers the rest.The rents set in 1981 were $540 for a studio, $673 for a onebedroom apartment, and $999for a three-bedroom apart-ment. The problem at TainoTowers, Gold says, is that therents remained at the 1981level until earlier this year.Housing analysts say thatSection 8 is usually considered a very generous subsidy,but agree that 1981 rents maywell have been inadequate tomeet operating costs in lateryears. But it was up to theowner and the manager torequest that HUD grant anincrease in the rent level. Oncea request wa s eventuallymade, HUD granted th eincrease and boosted th eannual subsidy. As ofJanuary1991, rental rates were set at$723 for a studio, $901 for aone-bedroom apartment and$1,338 for a three bedroomapartment.

"Giving more money is not going to solve the issue," sayEvette Zayas, a tenant activist. "Maybe it will solve maintenance problems. But the big issue is mismanagementand who is on the board and what their function is. I'vspent years just trying to find a copy of their by-laws!"

The failure to request a rent increase from HUD is jusone part of a larger problem at Taino Towers. Although the building was meant to provide a nationaexample of the merits of tenant management, thecurrent ownership group only includes two tenants anddoesn't meet regularly. One member is even a paid employee of the management company, the organization theboard is meant to oversee.Benjamin Flores, the board's chairman, is easily reachedany day of the week in the management suite of thcomplex. In a lengthy an d cordial interview in his officeFlores readily concedes that his board meets sporadically"We're meant to meemonthly, but lately wehaven't been doing that," hesays, noting that the last meeting was about a year ago.After repeated requestsFlores proffers a list of eighboard members, carefullycrossing out the name oJoseph Maya, who is no longeliving. The other board members are: Lucy Carter, EmilioHo, Juana Gilbert, Elsie IsaacSarah Wall and ThelmaCockerham.Here's what some of theboard members have to sayabout board meetings. LucyCarter, vice-chairman: "I'mnot an active board memberight now." Emilio Ho, second vice-chairman: "We havefailed in that area of meetingactively." Juana Gilbert: "Wedon 't meet regularly." SarahWall: "For the past five yearwe haven't had regular boardmeetings."

Despite his expertise as amanager, Marvin Gold sayshe can't explain why his company didn't move faster to request the increase. "I reallydon't have an answer to that,"he says. "We felt the Section 8money was enough to operatethe building. The rent increaseshould have been asked forsooner."The new increase includesmoney that is meant to be setSloppy Wortc Betty Screen says she has to fight to get basic repairs.

All of these individualhave served on the boardsince the early 1970s, andsome since 1969. They saythat active participationwaned after the developmenwas constructed, an d agreethat most decision-making inow left to Benjamin Floresaside for major repairs-$9 million over the next six years."We are now in the process of reconstruction," saysFlores. "If you come back in a year you'll see big, bigimprovements."Many tenants, who have been signing petitions forbetter conditions and struggling to negotiate with theowners and the management company, remain skeptical.12/DECEMBER 1991/CITY UMITS

"Since th e towers werecompleted, it didn't seem necessary to meet so often,explains Carter.Two of the board members, Juana Gilbert and SarahWall, live in the development and express dissatisfactionwith conditions-and an inability to prompt any change"We spent so much time seeing this place builtbu t it's jusgoing downhill," says Wall. "I t seems like there is nothing

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

13/28

you can do."As for the otherboard members, ElsieIsaac has moved toFlorida, according toGilbert an d Wall, andThelma Cockerhamworks in the management office of TainoTowers, receiving apaycheck from MarvinGold Management.Flores sees no conflictof interest. "She's justone board member, an dshe's a very independent person," he says.

Development, the federal agency that keepsTaino Towers alivewith ongoing subsidies.David Buchwalter,the chiefofHUD's loanmanagement branch,explains that th eagencyholds the mortgage for Taino Towers,offering the community owners a very lowone percent interestrate. The federal government also funnels$4.5 million annuallyto the building throughSection 8 housing subsidies to tenants.

Like Cockerham,Flores spends a goodpart of his days in themanagement office atTaino Towers, bu t hesays he doesn't receivea penny for his services.He explains that he

At the Helm: Benjamin Flores, the chairman of the community ownership group,says, "We may not be perfect but we've got nothing to hide. "

In another long andfriendly interview,Buchwalter repeatedlyexpresses concernabout conditions atearns his living working as a housing consultant, bu twavers when asked to give examples of groups he hasworked for. He asks: Is this article about Taino Towers orBenjamin Flores?Flores also keeps busy with local political workincluding the failed City Counci l campaign of William DelToro, an East Harlem politic ian who was recently slammedby the Daily News, Newsday and the state for financialindiscretions in the organization he runs, the HispanicHousing Task Force.Flores maintains that there are no similar indiscretions

at Taino Towers. Leaning back in his chair, he saysamiably,"We may not be perfect bu t we've got nothing tohide."The board chairman is only slightly less comfortablewhen pressed about the continuing empty space in the daycare center, the gymnasium and the swimming pool. It'sbeen at least 10 years that these facilities have beenvacant, but Flores promises that they may soon be occupied. "We're working with local groups to utilize thespace. There isn't money out there ..but we as a board arelooking for funding to get something started."Flores started his organizing career with the East Harlem Tenants Council, which organized rent strikes infreezing tenements, but today his attitude towards tenantshas changed. Asked to explain recurrent breakdowns inthe elevators, leaks in the building an d lapses in security,he cites faulty construction and insufficient operatingfunds. Then he blames the tenants, saying, "What tenantssay to you and what the facts are is not always thesame ..you fix up an apartment, then you go back a year ortwo later and the apartment is destroyed. Those are theones who complain the most."

ke Taino Towers, the federal office building inLower Manhat tan dominates its immediate landscape.This bureaucratic skyscraper is home to the localoffice of the Department of Housing and Urban

Taino Towers."Taino gets relatively intensive scrutinyfrom us," he says. "We're concerned about tenant complaints, concerned about the community space, concernedabout such issues as the elevators. It's a subsidized projectan d we want to look at it as carefully as we can."He acknowledges that reviews of Marvin Gold Management have led to less-than-stellar findings. "Clearly we'dlike to see things get better," he says. "But we thinkmanagement has made some significant strides." As anexample, he says there used to be about 70 empty apartments in the building, and now the vacancy number isdown to about 20.But what about the community owners? Buchwalterexpresses ignorance when told of the intermittent boardmeetings an d the board member who works for the management company. He says this could possibly be a conll.ict of interest, but stresses, "The internal workings of theboard of directors is not something we concern ourselveswith."This answer flies in the face of a new HUD policy,issued this March, which reinforces the agency's obligation to provide strict oversight of managers as well asowners in subsidized developments. In a follow-up interview, Buchwalter clarifies, "We do have oversight of theowners in so far as it impacts on the running of a project.Do we hold an owner accountable for conditions in abuilding-yes. Do we look over the minutes of boardmeetings-no. "Buchwalter acknowledges that an owner can be removed if conditions are so bad in a building that it is being"wasted," but says, "We feel the owner and the managingagent at Taino Towers have implemented some significantimprovements, that they're pointed in the right direction."HUD's reluctance to look deeper at Taino Towers is partof a larger pattern, according to Sherece West, the coordinator ofthe New York City HUD Tenants Coalition, whichis run by the Community Service Society, a research an dadvocacy group. "In general when I go to HUD I feel asthough I'm coming up against abrick wall," she says. "I see

CITY UMITS/DECEMBER 1991/13

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

14/28

a lot of deterioration in buildings . I go to HUD an d they letme know they have management reviews an d inspectionsthat lead to poor or unsatisfactory ratings. But absolutelynothing is done."Yates from the National Low Income Housing Coalitionagrees. "HUD generally has done some pretty lousy oversight of these properties. It's not unusual for propert ies tohave significant deterioration, pretty poor managementand for HUD to come by every year and not do anything.There are a lot of reasons for this. One is that HUD isincredibly understaffed. And until recently, they had noencouragement from the top to do anything about theproblems."He says that this was meant to change with the newrules reinforcing oversight, issued in March. But apparently there's a gap between Washington policy rhetoricand East Harlem reali y. Miriam Falcon-Lopez, the district

aide for Congressman Charles Rangel, has been hearincomplaints about Taino Towers and prodding HUD tbecome more active since 1989. She says getting cooperation "was like pulling teeth without Novocaine."

The "hands off" attitude at HUD makes sense withithe broader historical context. "There were onlthree brief periods in American history when thgovernment was pressured into building housinthat met with the standards of quality that we consideappropria te," says Peter Marcuse, an urban planning professor at Columbia University. "Taino Towers was built athe high point of one of those periods , bu t it outlived itsupport."What this demonstrates is the conservatism ofHUD,Struggtes and Unanswered Questions

The idea for the Taino Towers project was born in thelate 1960s, the brainchild of a tenants' rent strike infreezing, dilapidated, rat-infested East Harlem tenements.The East Harlem Tenants Council organized thestrikes, and attracted attention from the city's media. Ajournalist from the New York Post, James Wechsler,travelled uptown and was profoundly impressed bywhat he saw. His newspaper column about the frigidliving conditions in East Harlem inspired two sociallyconscious architects, Gerald Silverman and Robert Cika,to go to the neighborhood and offer their assistance.Silverman and Cika met with the leaders of the EastHarlem Tenants Council and they started to dream of amodel project, a development that would combinewell-designed housing with on-site education, healthcare, commercial stores and plentifu l space for recreation. The project would be an alternative to oppressive, box-like public housing, and it would be cheaperto build because the commercial spaces would subsi-,dize the apartments.They pu t their ideas down on paper and started topound on the doors of local politicians: the senatorsRobert Kennedy and Jacob Javits, and Rep. HermanBadillo. In 1967, HUD awarded $19 million for TainoTowers under the National Housing Act, but the cityand state governments opposed the plan, considering ittoo costly and ambitious. Years passed and nothinghappened. In 1970, the federal government asked fortheir money back and Taino Towers seemed doomed.But after intense lobbying from the Puerto Ricancommunity and some design modifications, HUD revived the plan. The federal government promised $39million in loan guarantees, enabling the communityorganizers to raise construction funds from New Yorkbanks. HUD agreed to pay most of the interest, plusprovide generous Section 8 rental subsidies.The tenements on the site were razed and the projectbroke ground in 1972, but that was just the beginning ofa new series of headaches. Construction costs ballooned and the general contractor, S.S. Silverblatt,alleged that he didn't recei ve enough money for the job.

14/DECEMBER 1991/CITY UMns

Silverblatt tried to cu t corners while the communitygroup and the architects struggled to maintain theoriginal plan. Work stopped in 1976; the project wasbroke, an d HUD assumed control of the mortgage."HUD sabotaged the project by identifying with thegeneral contractor instead of the architects and thecommunity," says Robert Nichol, who was projectdirector for the East Harlem Redevelopment Project, aprecursor of the pilot block group. "By their interference, they allowed self-serving elements of thecommunity to gain control of the board." Nichol quitthe project in frustration, and todayhe lives in Bozeman,Montana.Bickering ensued, and the project was dealt a tripleblow: while the nearly-completed development satidle, vandals came in and wreaked havoc. Presidentialhopeful Ronald Reagan excoriated Taino Towers in hiscampaign, describing it as an outrageous example ofluxury housing for the poor. And New York City'srecessionmeant that human service agencies lost interest in renting the commercial space that was supposedto keep the development afloat.Finally, the owners of the towers managed to win apromise for an extra $10 million from Washington to getthe project completed. Tenants started to move in by1979-but the final tower wasn't opened until 1984.Questions of ownership responsibility crept into thepicture early on. According to Benjamin Flores, some ofthe final construction work was done by Junque Development Corporation, a for-profit entity created by theownership group. And an early management contractwent to another for-profit spin-off with close ties to theowners, Junque Management Corporation, ru n by aformer chairman of the East Harlem Pilot Block board,Julio Vazquez. The company was dismissed by HUD,apparently because of conflicts of interests.By the time the towers were up and running, officialsat HUD ha d distanced themselves from the project. Ina New York Times article, HUD's deputy housing director, Edward Springer, said, "There are going to be manyunanswered questions about this project for a very longtime." 0 Lisa Glazer

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

15/28

he continues."Spitefulness isn'texactly th e rightword. I'm thinkingof a word in German,Schedenjreude. I tmeans taking plea-sure in otherpeople's pain. I sus-pect that underneath, there's aphilosophical pointof view at HUD thatthis project shouldnever have beendone, that it wasnever expected tosucceed."Marcuse's inter-pretation stilldoesn't fully explain

Lost Hoops: The Taino Towers gym is damaged and unused. So is the swimming pool.

housing who haveth e greatest stakean d care the mostabout their housing," Achtenbergsays firmly. "Theyare the ones whocan en-sure thepublic interest con-tinues to be met. Itmakes sense to pu thousing in thehands of community people-aslong has they haveth e financial resources, the organi-zational structurean d the technicalhelp they need to

the failure of he community owners. "The message ofthisis not a politically happyone for our side," says Achtenberg,who has worked with nonprofit housing groups across thecountry. "It's been such a fight to give an equal playingfield to nonprofit owners. Both HUD and the communityhave a responsibility to do what needs to be done to correctthe situation."Despite the example of Taino Towers, Achtenbergremains a firm believer in community control, althoughsome advocates say that other models, such as Com-munity Land Trusts or Mutual Housing Associations, maybe more effective. "Ultimately it's the people who live in

make it work."Tenants who want to improve the way things work ofTaino Towers may find some ammunition for their battlesin the recollections of Yolanda Sanchez, an early EastHarlem Pilot Blockmember who left the board many yearsago but is still active in the local community. "In the1960s, all of us believed in community control," sheremembers. "The idea was that tenants would be orga-nized and eventually they would take over the board. Webelieved tenants ha d the ability an d the right to governtheir own home ." Right now, she says, the last thing theowners want is active tenants-but that doesn't mean itcan't be done. 0

BankersliustCompanyCommunity Development Group

A resource for the non--profitdevelopment community

Gary Hattem, Vice President280 Park Avenue,19 West New York, New York 10017

Tel: 212A54,3487 FAX 454,2380CITY UMITS/DECEMBER 1991/15

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

16/28

By Mary Keefe

Climbing the Job LadderThousands of women in the health care industry arestuck in the lowest-paying jobs-and it's tough tomove up.In spite of the odds against her,Jeanette Mitchell is determined tobe a nurse. At 33 , she's been supporting her two children with herincome as a home health aide for sixyears. She only makes $6.50 an hour,and until recently she hasn't had thetime or money to gain the skills sheneeds to move up the career ladderinto a better-paying position.That's changed since she joined afoundation-funded program at a small, workerowned home health carebusiness in the Bronx,the Cooperative HomeCare Agency. She's finished two years of prenursing school, and inSeptember she startedth e clinical trainingphase of a nursing program atlona College. Sheworks weekdays from 9a.m. to 1 p.m. and everyother weekend, and travels to Yonkers four nightsa week for classes andtraining.The agency providesher with a stipend thathelps her pay the billswhile she works parttime and provides constant support withtutoring and counseling.Her sister takes care ofthe kids every evening.Still, it 's not easy ."Sometimes I fall asleeptrying to read," she says.

ing: "It's going to be very, very tough."Men and women-most lywomen-are stuck in entry level jobslike Mitchell's throughout the healthcare field. Many of them live in thecity's poorest neighborhoods, and theycanbarely support their families. Theyare hospital and nursing homeorderlies, nurse's aides, home healthcare workers and others. Yet, despitethe fact that New York City has a

move up the pay scale an d fill thempty positions. A few assistancprograms do exist for entry-levehealth workers, but they are very smaand very new."Unfortunately, from what I casee, there are very few real successesin the training programs, says Margaret McNally, director of Ladders iNursing Careers (UNC) , a small burespected pilot assistance effort. Thhospitals and schools "are openintheir eyes bu t they are only halfopen,she says. "They have ideas, bu t thehave to put it all together to make thpatchwork quilt."Jobs That Have Real MeaningHealth care is one of the few industries with explosive growth in thesrecessionary times. There are abou75,000 home health carworkers in New YorCity. Almost all of thpeople that have thesjobs are black and Hispanic women, most othem have no higschool diploma, an d thmajority are single-paents. But the pay is onlslightly more than wefare. The average wagis about $10,000 peyear, says Rick Surpinpresident ofCooperati v

Home Care."Home health care iseen as a dead-end thapeople will not go beyond," says Surpin"There is not a notiothat we want to traipeople for jobs that havreal meaning. Just along as you get someonworking it is [considered] okay," he addsbut, as he sees it, there'little incentive to wori f the wages won't pulyou out of poverty .Entry-level worker

:I : in hospitals and nursinghomesaresomewhabetter off. Starting sala

Mitchell is an ex tremely unusual caseamong home healthaides. Many of her fellow workers can see noway ou t of their deadend jobs. "Once you're ahome health aide that'sit," they tell her. Morethan half of th e 25

' - - - - ~ ' - - - - - - - - - - __________ _'____ltn ries can go as high aMoving Up: Jeanette Mitchell trains to be a nurse at St. Joseph 'sMedical Center in Yonkers . She says its a struggle.

women that started the program withMitchell two years ago have droppedou t. She has some advice for otherswho want to attempt what she is do-iI/DECEMBER 1991/CITY UMITS

severe shortage of trained nurses andhospital technicians, most of thesemen an d women can't find the financial and technical help they need to

$20,000, with benefitsBut about a third of almedical-related jobs inhospitals and nursinhomes, where more than 250,000NewYorkers are employed, are filled bpeople with high school degrees oless. For such workers, there's littl

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

17/28

room for advancement, regardless ofhow much they learn on the job-theaverage maximum salary is onlyslightly higher than the average starting salary.It's not lack of interest that's holding people back, insists EdwardSalsberg, head of the Bureau of HealthResources Development at the state'sDepartment of Health. In 1989 Salsbergwas staff director of the New YorkLabor - Health Industry Task Force,whose report concluded that "a substantial part of the health care laborforce is hindered from reaching itsoptimal potential."System Has FailedEducation is the key to climbingthe career ladder in health care. Butthe system is not designed to educateworking men and women with families an d very low incomes. Tuitioncosts are daunting, and adult studentshave little free time to study or attendclasses. "For the most part, our education system has failed the non-traditional students," says Salsberg. Butheis hopeful that this wi ll change. "Whenyou make education available andconvenient for workers, there are literally thousands of existing workerswho will jump at the opportunity," hesays.But when they jump, they don'talways land on their feet. Dolores Perinof the Center for Advanced Studies inEducation at the City University ofNew York graduate school, cites aCUNY community college nursingprogram with an 85 percent drop-outrate. Students were "expecting toomuch of themselves," she says, an doften were swamped by the conflicting pressures of work, home an dschool.The government has begun torespond to the needs of the healthsystem for trained employees. InJanuary, 1990, the state created anincentive program that funnels extraMedicaid funds to hospitals and otherinstitutions who provide careertraining, education or day care to theirstaff. In 1991, the incentive channeleda hefty amount-$45.8 million-to thehospitals. Two-thirds of the moneywent to NewYork City, and two-thirdsof that went into training programs foremployees. At this early stage, there'sno way of knowing how much of thatmoney reached low-level employees.Salsberg says his office is currentlyevaluating the program.Unions are taking advantage of the

incentive. Local 1199 of the Hospitaland Health Care Employees, a unionthat represents 100,000 workers inthe city, runs high school equivalencyand other remedial programs for itsmembers. By tying into the Medicaidmoney, Local 1199 has given about300 union members paid time off togo to school to study nursing or othertechnical subjects. Theunion providescounseling and tutoring support. District Council 37 of the American Federation of State, City and Municipal

A few assistanceprograms do exist,but they are verysmall and very

new.

Employees (AFSCME) has similarprograms for workers in city-runinstitutions.The Greater New York HospitalAssociation runs the LINC projectwithMedicaid money and some privatefunds. Participants get individualizedtutoring and counseling. While theyare in nursing school they work parttime, are paid full-time and are eligiblefor a tuition grant. In exchange theyagree to work at the sponsoringinstitution for a certain amount oftime after they graduate.Still, relatively few people havebeen able to participate in theseprograms. Almost 5,000 peopleapplied to participate in the L1NCprogram, but only 324 were acceptedand enrolled. By the en d of Decemberonly about 100 of them will havegraduated.The Money Runs Out"There is a terrible shortage" ofpre-college programs focused specifically on nursing, says Salsberg. Critics of the existing efforts say that theyare no t permanent. Two health programs coordinatedby the Consortiumfor Worker Education, a coalition of22 unions, have only 12 to 18 monthsof funding. Once the money runs out,

the programs scramble for money andfewer workers can participate."The problems call for more thansporadic, although successful, initiatives," says Peggy Powell, the executi ve director of th e Health CareAssociation Training Institute. Shesays the existing pilot programs haveto find a steady, continuous source offunding that will last many years, sothey can become permanent. Rightnow, McNally says, "you have enoughmoney to start people on the path ..an d then the money to move peoplefurther along runs out."Some advocates say that entry-levelhealth care workers who don't wantor can't manage a formal universityeducation should still have access totraining programs that can hel p themmove upward in the industry. Somehospitals offer that now, but it's inconsistent and provides little reward,says Eric Shtob, director of the Local1199 Education Fund. For homehealth workers, the most anyoneachieves through non-university training is a small raise-there's rarely anychange in a worker's responsibilities,regardless of her non-degree trainingor experience.Still, a few women like JeanetteMitchell have been able to successfully start the move beyond their underpaid home health care jobs. Theuneven path to a better wage requiresa remarkable amount of stamina andfortitude. Judi thK. (nother real name),whose boss doesn't know about herlong term plans, is a home health aidewho is just starting a program run bythe consortium. She works a 2 p.m. to10 p.m. shift, five days a week inBrooklyn. Two mornings a week she'sin Manhattan working on her highschool equivalency degree. Nursingschool would mean working nights,going to school during the day, andsending the two youngest of her threechildren to live with her sister inTrinidad. But she has no doubts aboutwhere she's headed. She sets her jawan d says, "I will do it for myself." 0

TAKEOVERA documentary about thehomeless helping themselves isavailable on video from SkylightPictures. The cost is $20 forindividuals,$50 forinstitutions.

Call (212) 947-5333CITY UMITS/DECEMBER 1991/17

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

18/28

Toil and TroubleLow-income employment during the recession.

New York City's economicinfirmity is hitting low-incomeneighborhoods doubly hard.No t only ar e governmentfunded social services, health carecenters and youth programs disappearing, bu t the low-paying jobs thatkeep families and local businessesjust barely afloat are beginning to vanish as well.The city's official unemploymentrate has gone way up in the past yearand a half-two full percentage pointsabove what it was during the summerof 1990. The actual body count of theunemployed: 279,000 as of October.But the so-called "official" ratemisses the true picture of unemployment an d under-employment. Thefederal survey that establishes theunemployment rate counts part-timeworkers, even those who work justone hour a week, as fully employed.And the government doesn't evencount men and women who haven't

taken concrete steps toward finding ajob during the month prior to thesurvey-they are called"discouragedworkers" rather than unemployed. I fpart-timers an d discouraged workerswere taken into consideration, says]osephineNieves, the city's labor commissioner, New York City'S trueunemployment rate could be as highas 28 percent.Paradoxically, in the first year ortwo of the recession the number oflow-wage jobs commonly filled byminority workers continued to increase. They were in industries likehealth care and social work, whereminorities tend to hold the jobs on thelowest rungs an d whites stand at thetop. Many of these new jobs paidbetween $10,000 and $19,000, not thekind of paycheck that can sustain asingle-parent family.During the last decade, the city'seconomy underwent a sea-change.Manufacturing businesses continued

to leave town or close up shop, anone-third of the manufacturing jodisappeared. Meanwhile the serviindustries moved in, adding hundreof thousands of jobs in busineservices and health, education asocial work. And employment oppotunities within the local governmesoared. But the business services copanies cut back drastically duri1990 and 1991. And the growthhealth, education and social servicwhich was subsidized by the goverment, is now slowing down.That means the period of growthat added low-wage jobs to the NeYork economy is ending. Claims funemployment insurance froworkers that lost their jobs thsummer in service industries, retsales an d government are all soarinThese are some of the sectors wheminorities have found the most join recent years.As the city's economy shifts ward providing very-low-wage jofor black and Hispanic workers, atumbles deeper into a recession wheeven those low-paying jobs begindisappear, the outlook for the citbattered neighborhoods becomes evmore bleak. 0 Andrew White

Unemployed Workers in New York City350

300

';250===200.5

50

oJ FMAMJ J ASO NO J FMAMJ J ASO NOJ FMAMJ J ASO NOJ FMAMJ J ASO NO J FMAMJ J AS

1987 1988 1989 1990 1991Source: u.s. Dept. of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics18/DECEMBER 1991/CITY UMITS

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

19/28

Where the Jobs Are...

220

Employment in New York City'sHeaHh Care Industry

200 ~ - - - - - - + - - - - - - - ~ - - - - - - ~ =m=.i 180 1-------+------: : :-S

1201977 .1980Source: NYS Dept. of Labor

1983 1986Data for private sector only, in four NYC boroughs (Bronx not available)

1989

Unemployment in the Low-Income EconomyNumber of people receiving unemployment benefitsafter losing jobs in selected industries, NYC

Sept 1991 Sept 1989

Services

o 10,000 20,000 30,000Source: NYS Dept. of Labor

. .and Who Has Them:Employment in HeaHh Care Industryby Ethnicity and Race

All Employees:

Hispanic14%

Managers:

Hispanic8%

Service Workers:

Asian4%

Black36%

Source: Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.Data for private sector only, 1989, in NYC

CITY UMITS/DECEMBER 1991/19

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1991 Issue

20/28

I I ' ni, I l\ill By Barbara FeddersWhy Doesn'tShe Just Leave?As an advocate for women whoare being battered and who aresurvivors of domestic violence,I encounter a good deal ofignorance-both from people outsidethe field and from other social serviceproviders-of th e psychologicalprocesses women typically go throughbefore they candecide to leavea violent relationship. Whydoesn't she justleave , theywonder, without understanding that awoman mayblame herself;or believe hermate's promises that thistime is the lasttime she'll behit; or have solittle self-esteem that she believes shecannot live without the abuser.Along with working through thesedifficult emotions, poor women inNew York City also face the realitythat leaving a mate who physicallybatters them means confronting awelfare an d housing bureaucracy thatwill emotionally batter them. Theirreasons for not leaving are clearlyrelated to the city's Human ResourcesAdministration's failure to develop ahumane set of policies for addressingthe needs of poor women who arebattered. Why doesn 't she leave?Because leaving may be as bad asstaying.A 1990 Ford Foundation reportnotes that 50 percent of all homelesswomen and children in this countryare homeless because they are fleeingdomestic violence. New York Cityfunds a pitiful 46 7 beds in domesticviolence shelters . The handful ofprivate shelters are quite small andare difficult for a woman in crisis to

City View is a forum for opinionand does no t necessarily reflectthe views of City Limits.20 /DECEMBER 1991/CITY UMITS

find out about, as the city's DomesticViolence Hotline does not refer themthere.It is not surprising that, accordingto a 1988 study cited by Joan Zorza,senior attorney at the National Battered Women's Law Project,59 percentof those women seeking emergencyhousing at a domestic violence shelter in New York City are turned away.Those few lucky enough to get in arethen eligible for permanent, cityowned housing for the homeless.However, the 90-day maximum stay

policy in the domestic violence shelters is unrealistic, as the wait forpriority housing is six to 18 months.No Place to GoThe city's 1991 budget includedfunding for an additional 150 beds.The Dinkins administration announced the funding in May, 1990; todate, most of the money has not beenreleased. Adria Hillman of the NewYork Women's Foundation, which ,along with the Coalition of BatteredWomen's Advocates an d severaldomestic-violence shelters, initiallylobbied for the funding, believes thecity is stonewalling an d wonderswhether the money will everbe spent."It is difficult to understand wherethe money is coming from to build allthe ne w large [regular homeless]shelters the city wants to build whenwe can 't get the money we werepromised for the domestic violenceshelters ," she says.Why doesn 't she leave? Because noshelter will have her. With so littlespace in the City's domestic violenceshelter system,more and more womenwith children are turning to the regularhomeless shelter system for families.In fact , studies on the percentage ofwomen who move to the homelessshelter system because of domesticviolence give the number as anywherefrom 21 to 50 percent. The steady andmuch-reported increase in the numberof all families seeking emergencyshelter has led the city to proposescreening procedures that would"weed out" those who aren 't trulyneedy. Crowded shelters and tighteradmission requirements do not bode