Character Education: Lessons for Teaching Social and ......Character Education: Lessons for Teaching...

Transcript of Character Education: Lessons for Teaching Social and ......Character Education: Lessons for Teaching...

Character Education: Lessons for TeachingSocial and Emotional Competence

Rita Coombs Richardson, Homer Toison, Tse-YangHuang, andYi-Hsuan Lee

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether a social skills program. Connectingwith Other: LessonsJorTeaching Social and Emotional Competence, would enable students withdisabilities in inclusive classrooms to develop skills to facilitate socialization with peerswith and without disabilities. Students' growth was measured only in terms of teacherperceptions, because of the absence of preprogram assessments of the targeted students'social skills. The results of the study indicate reasonable assurance that the students didgrow in the skill areas and were able to interact positively with their peers.

KEY WORDS: character development;proactive behavior management; social skills

School social workers' role includes pro-viding support Co teachers and parents invarious areas. Increasingly, school social

workers are presenting workshops to teacherson the prevention of social problems studentsdisplay in schools (Men-Meares, Washington,& Welsh, 1996). Teaching social and emotionalskills is character education. Character educationrests on the principle that teaching for characteris important for a society that values democracy.A democratic society is not only based on socialequahty—its citizens are also expected to behaveresponsibly, respect other people's diversities, ac-cept what is fair and just, and show concern forthe common good by helping others. Charactereducation includes the affective and the cogni-tive qualities of a person. Because emotionsplay an essential role in making final decisionsbetween good and bad choices, children needto be guided as they mature in their social andemotional development. Healthy social matura-tion of children depends upon their learning andinternalizing standards of acceptable conduct aswell as transferring and applying these standardsin directing their behavior in various situations(Berk, 2007).

The No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of2001 strongly emphasizes scientifically basedpractices (Wilde,2007).The U.S.Department ofEducation requires that aU instruction, cognitiveas well as physical and affective, be guided bytheory and strictly evaluated so that it actually

does what it is intended to do (Coalition forEvidence-Based Policy, 2002). The measure-ment of effectiveness is critical to the validity ofa character education program. Such programsshould be validated and replicated by researchersin the field (National Institute on Drug Abuse,2008). Various character education programshave been studied for their usefulness, andresearch has supported significant correlationsbetween character education instruction anda decline in discipline problems as well as im-provements in academic performance (Roeser,Eccles, & SamerofF, 2000). The Collaborativefor Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning(CASEL) has fostered research to show a con-nection between Social and Emotional Learning(SEL) programs and academic success (CASEL,2003,2008). CASEL's mission is to identify anddocument how SEL programming coordinateswith and adds value to other approaches thataddress children's successful development. TheConnecting with Others: Lessons for Teaching Socialand Emotional Competence series is included inCASEL's Safe and Sound list of SEL programs(CASEL, 2003,2008).

INCLUSION AND FRIENDSHIPSStudents with mild to severe cognitive, physical,and behavioral disabilities have been includedin general education classes for many years, butresearch indicates that their friendships withnondisabled peers stiE need improvement (Saenz,

CCC Code: 1532-8759/09 $3.00 C2009 National Association of Sociai Workers 71

The lessons in the Connecting with Othersprogram are based on three theoretical

frameworks: transactional analysis, positiveassertion training, and cognitive behavior

modification.

2003). One of the reasons is that both groupsof students frequently lack social skills and needmore opportunities for quality social inclusion.Many children with and without disabilities havenever learned appropriate behaviors for socialsettings situations in which they are required tointeract and cope with others. Taylor and col-leagues (2002) suggested that teachers shouldmanipulate the environment and directly teachsocial skills for promoting friendships betweenchildren with disabilities and their nondisabledpeers. How should classroom teachers respondto the inclusion concept? They should be openand honest about disabilities, make disabilitya comfortable concept, and create social op-portunities for friendships to develop betweenall students. Collaboration between special andgeneral educators is crucial in achieving thesegoals (Calloway, 1999). Connecting with Others:Lessons for Teaching Social and Emotional Compe-tence is based on a friendship model developedby Evans and Richardson (1989) to encourageteachers to increase positive interactions in aninclusive classroom.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONConnecting with Others [Lessons for Teaching Socialand Emotional Competence Volume I (gradesK-2) (Richardson, 1996a) and Volume II(grades 3-5) (Richardson, 1996b) were origi-nally developed with a Louisiana state grant tosupport teachers in their instruction of prosocialskills and to facilitate inclusion of students withdisabilities in regular classroom settings. Thecurriculum includes 30 lessons divided into sixskill areas: Concept of Self and Others, Social-ization, Problem Solving/Conflict Resolution,Communication, Sharing, and Caring/Empa-thy. Each lesson follows a specific lesson cycle,and goals, objectives, and materials are included

for every activity. The program was developedwith practical utility as a primary goal. Theteacher directly teaches the skill and involvesthe students through guided questions whileproviding prompts and feedback. The teachingis followed by a brief assessment to check forunderstanding.The students engage in teacher-guided and independent activities following theinstruction. The guided activity involves thestudents working in heterogeneous cooperativegroups.The independent practice activity allowsthe teacher to observe the students' learningstyles and individual abilities. A summary sec-tion synthesizes the information and concludeswith optional enrichment activities.

The instructional steps for each lesson arebased on the findings of educational researchon direct instruction and cooperative learning.Prater and colleagues (1998) compared threeprocedures for teaching social skills to studentswith behavior and learning problems.The groupwho received teacher-directed instructionimproved significantly in listening, problem-solving, and negotiating skills during role-playsituations. Rutherford and colleagues (1998)implemented a cooperative group structure anddirect instruction in promoting social commu-nication among female adolescents.The resultsindicated systematic increases in appropriatecommunication skills.

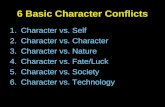

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKThe lessons in the Connecting with Others pro-gram are based on three theoretical frameworks:transactional analysis (TA) (Freed, 1991),positiveassertion training (PAT) (Alberti & Emmons,2001), and cognitive behavior modification(CBM) (Meichenbaum, 1977). A "GettingStarted" section describes each theoreticalconcept in a concrete, practical, and compre-hensible manner to give students a context forsubsequent skills lessons.The program features acartoon character, K.T Cockatiel, who appearsperiodically to explain concepts and provideexamples. ;

The ego states of TA are referred to as fiveattitudes: the Impulsive Me and the EnthusiasticMe (the Child), the Bossy Me and the CaringMe (the Parent), and the Thinking Me (the

72 Children & Schools VOLUME 31, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2009

Adult). The students are taught self-awarenessand awareness of others by examining attitudesand behaviors in various situations and by mak-ing an effort to be sensitive to the feelings ofothers in interactions.

PAT focuses on cognitive, affective, and be-havioral procedures to increase self-advocacyand interpersonal communication. Enipatheticassertion as well as direct assertion are taught andexemplified in numerous situations (for example:direct assertion: "No I don't need your help, Ican do it myself"; indirect assertion:"Thank youfor wanting to help, but I can do it myself"). Inaddition, time, place, and situation are examinedin relation to assertive behaviors (For example: itis not wise to be assertive in certain dangeroussituations or when reprimanded by an angryadult in authority; refraining from an assertiveresponse until calm and reason are restored doesnot indicate passivity).

Teachers can apply principles of cognitiverestructuring through CBM procedures. Stu-dents are guided to analyze the logic of theirthinking and are taught to change inappropri-ate behaviors by examining their emotions andthe consequences of their behaviors.Their nextstep is to plan and evaluate alternative behav-iors. Students are introduced to the "thinkingsteps" "Stop," "Think," "Plan," and "Check" tomonitor their behaviors. Students use relaxationtechniques, guided imagery, and self-chosenstrategies to put their inappropriate behaviors onhold. During the second step, the teacher guidesstudents in thinking of all the consequences oftheir behavior.They learn to plan and to imple-ment their plans. The last step. Check, involvesself-evaluation and self-reinforcement.

TEACHING AND LEARNING STRATEGIESSeveral strategies are consistently used through-out the program to teach the intended skills.Specifically, these strategies include storytelling,bibliotherapy, relaxation, modeling, coaching,behavior rehearsal, role playing, verbal media-tion, creative expression (for example, art, music,poetry, and puppetry), creative visualization,cooperative learning, and transfer learning.Because generalization and transfer of skillsare learned best when parents are involved.

the program includes newsletters to informparents or other caretakers of what is currentlybeing taught and to elicit their cooperation inreinforcing the skills at home. The newslettersinclude specific homework for the parentsand the child. Bibliotherapy and storytellingare powerful strategies to teach children socialskills. The program includes lists of correlationsof children's literature to every skill area. Inaddition, teachers can add to the lists accord-ing to books available in their school libraries.Children tend to tune out adults who are- con-stantly telling them to behave. Role playing andbehavior rehearsals are two strategies that canchange behavior and attitudes without sermon-izing. Teachers must model the skills they wishtheir students to acquire and use a variety ofmodehng strategies, such as puppetry, to engagethe students in developing ethical characters.

PURPOSE OF THE STUDYThe purpose of this study was to investigatewhether a social skills program. Connecting withOther: Lessons for Teaching Social and EmotionalCompetence, would enable students with dis-abilities in inclusive classrooms to develop skillsthat would facilitate socialization with peers withand without disabilities. The research questionaddressed the students' acquisition of socialskills as a result of the training. Did the targetedstudents with disabilities in inclusive classroomsshow growth in various skills categories as aresult of social skills instruction? The identifiedskills categories were the following: Concept ofSelf and Others, Socialization, Problem Solv-ing/Conflict Resolution, Communication,Sharing, and Empathy/Caring. It was predictedthat growth in these skills would promote ac-ceptance of students with disabilities by theirnondisabled peers.

METHODParticipantsThe 25 participating students were selected fromfive schools districts. Seventeen students wereidentified as having learning disabilities, andeight students were classified as having behaviordisorders.The students with learning disabilitiesin grades 3 and 4 received most of their instruc-

CooMBS R I C H A R D S O N ET AL. / Character Education: Teaching Social and Emotional Competence 73

tion in a general education classroom; bowever,tbey also received a period of reading instructionin tbe resource room.Tbe students witb bebaviordisorders received all of tbeir instruction in ageneral education classroom. Of tbe 25 students,80 percent were African American, 17 percentwere wbite, and 3 percent were Asian. Tbe stu-dents ranged in age from 9 to 13 years old. Tbeteacbers reported tbat botb groups of studentsdemonstrated antisocial bebaviors, includinginability to make friends, noncompliance, im-pulsivity, inability to grasp future consequencesof bebavior, inability to delay gratification, andinability to self-regulate emotions.Tbe programwas implemented using activities from VolumeI (grades K-2) and Volume II (grades 3-5) ofConnecting with Others: LessonsforTeaching Socialand Emotional Competence.

Twenty-one educators implemented tbeprogram. Eigbteen were general educationteacbers, two were speecb tberapists, and onewas a counselor. Tbe counselor and tbe speecbtberapists worked witb tbe general educators ina team-teacbing environment to implement tbeprogram.Two of tbe teacbers were not assignedinclusive classrooms and implemented tbe pro-gram in otber classrooms containing studentswitb disabilities. Tbe 19 female and two maleteacbers were employed in public scbools infive parisbes in Louisiana. Tbe average teacb-ing experience of tbe 18 general educators wasseven years, witb 16 being tbe bigbest numberand four being tbe lowest number of teacbingyears. AU bad earned university credit bours inan introductory course to special education intbeir teacber training program and bad receivedcontinuing education credits tbrougb tbeir dis-trict training program.

ResearchTbe Social SkiUs and Attitude Scale (SSAS) wasdeveloped to assess tbe social skills included intbe program. Tbis instrument uses a five-pointLikert scale to measure tbe level to wbicb astudent reflects or demonstrates tbe skill or traitidentified in a statement.Tbere are 50 items ontbe instrument, and tbe number of items perskill category varies from four in tbe Sbaringcategory to 13 in tbe Problem Solving/Conflict

Resolution category. Tbe perceived growtb ofeacb student in tbe six areas was assessed by aparticipating teacber, a teacber wbo interactedwitb tbe student (control), and tbe special edu-cation teacber. Tbe reliabilities of tbe six scalesranged from .84 for Sbaring to .56 for ProblemSolving/Conflict Resolution. Tbe overall reli-ability estimate was .75.Tbe analyses were madein terms of scale scores and reported as meandifferences between teacber category and pretestand posttest. Tbe tbree assessing teacbers wereselected on tbe basis of tbeir familiarity witbtbe students and tbeir parents.Tbe data analysiscompared cbanges from pretest to posttest bytbe students as perceived by tbe tbree teacb-ers, to determine wbetber tbe Connecting withOthers: Lessons forTeaching Social and EmotionalCompetence program bad an impact on tbe socialskills of tbe targeted students and wbetber tbestudents were able to generalize tbe learnedsocial skills across teacbers.

ProcedurePrior to implementing tbe program, tbe 21educators attended 35 bours (seven sessions) oftraining in social skills instruction and imple-mentation. Tbe worksbop was offered by tbeUniversity of Louisiana at Lafayette and ledby a professor of special education. Tbe focusof tbe training was on developing activitiesbased on tbe framework of tbe Connectingwith Others program. Tbe teacbers worked incollaborative groups and identified areas for asocial—emotional curriculum. Tbey originallydesignated eigbt areas; bowever, following mucbdiscussion, tbey agreed on tbe following six skillareas: Concept of Self and Otbers, Socialization,Conflict Resolution/Problem Solving, Com-munication, Sbaring, and Love/Caring. Tbeycreated activities for eacb skill area under tbeguidance of tbe professor.

Upon returning to tbeir scbools, tbe teacberstargeted students in tbeir classrooms identified asbaving a disability wbo were receiving instruc-tion in inclusive general education classroomsand in special education resource rooms.Tbe tar-geted 25 students bad displayed antisocial bebav-iors documented by referrals to tbe scbool office.Tbe SSAS was administered for eacb student in

74 Children &Schook VOLUME 31, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2009

the study by graduate students at the university.The teachers were instructed to teach selectedsocial skills lessons class-wide three times perweek for 40 minutes for 16 weeks. In addition,they addressed social behaviors throughout eachday according to the demands of the situation.Five students with disabilities were targeted inschools A, D, and E. Six students were selectedin school B, and four students were selected inschool C. The schools were all Title I schools,which meant that 40 percent of the studentsreceived reduced-fee or free lunches.With oneexception, the school districts were rural. Toassess the effects of the lessons, a checklist wasused to document the behaviors of the targetedstudents.

Data AnalysisThe hypothesis was that participation in thesocial skills program would improve the targetedsocial skills of the 25 students with learningand behavior problems who were instructedin a general education classroom.The obtainedraw scores were subjected to a 3 (Teacher) x2 (Time) factorial analysis with repeats on theTime factor. Any significant interactions wereprobed using simple main effects (SME) analysis.Any SME profiles that were declared to havesignificance were explored using least significantdifference testing.

The means and standard deviations of thestudents (N = 25) for the six scales at pre- andposttest are presented inTable l.The differencesand similarities of the means were examinedusing analyses of variance (ANOVAs).

Table 1: Means and Standard Deviationsfor Each Scale Pretest and Posttest

Concept of Self and OthersSocializationProblem Solving/Conflict

ResolutionCommunicationSharingCaring/Empathy

19.6718.71

33.2323.9310.3323.21

2.361.53

2.861.651.411.99

31.0928.27

46.1632.2111.6730.19

2.682.13

4.722.621.672.88

The summary ANOVAs for the scales arepresented in Table 2. An examination of thetable indicates that except for the Socializationscale, the ratings of the three groups of teach-ers did vary significantly, and differences acrossTime were significant in terms of all the scales.The effect sizes associated with the analyses arepresented as partial eta^ in Table 2. Except forthe Teacher x Time interaction for Sharing,the effect sizes would be judged to be moder-ate to large.

Across the five scales in which the Teacher xTime interaction was probed, the participatingteacher tended to give ratings that were similarto those of either one or both of the other twoteachers. Where significantly different ratingswere detected, they were between the specialeducation and control teachers.

The student changes across Time were sig-nificant for all three raters, with the mean atpostprogram always being greater than thatobtained at preprogram. The effect sizes forall the SMEs were judge to be very large. Thiswould indicate a substantial practical significanceeven for the relatively small sample size usedin this study.

DISCUSSIONImportance of the StudyThe purpose of this study was to investigatewhether a social skills program, Connecting withOther: Lessons for Teaching Social and EmotionalCompetence, would enable students with dis-abilities in inclusive classrooms to develop skillsto facilitate socialization with peers with andwithout disabilities. It was necessary to mea-sure student growth only in terms of the dataprovided by the SSAS. The results of the studyindicate reasonable assurance that the studentsdid grow in the skill areas or, at the very least,that all three groups of teachers were cognizantof growth in these areas. The outcomes of thestudy indicate growth of the students' socialskills resulting from instruction from the Con-necting with Others: Lessons for Teaching Social andEmotional Competencies program.The findings ofthis study are consistent with those of numerousstudies that address the importance of teachingsocial skills to students with disabilities. Schlitz

C O O M B S R I C H A R D S O N ET AL. / Character Education: Teaching Social and Emotional Competence 75

Table 2: Summary Analysesof Variance for Each Scale

|SSIÏR33Concept of Selfand Others

Teacher (R)Time (T)R x T

SocializationRTR x T

Problem Solving/Conflict Resolution

RTR x T

CommunicationRTR x T

SharingRTR x T

Caring/EmpathyRTR x T

GÎ?

212

212

212

212

21

2

212

>

7.0062456.351

32.719

2.1441205.367

9.144

53.8731471.114

28.458

17.665769.103

22.72

4.51585.714

.264

5.756647.023

30.378

IJ) &SP

.002** .226

.001** .990

.001** .577

.128 .082

.001** .980

.001** .276

.001** .692

.001** .984

.001** .542

,001** .424.001** .970.001** .486

.016* .158

.001** .781

.612 .011

.006** .193

.001** .964

.001** .559

and Schlitz (2001) found that direct teaching ofsocial skills resulted in significant improvementin the behaviors of students with inoderatecognitive delays. A study with students on theautism spectrum by Epp (2008) indicated thatthe results of social skills instruction showedimprovement in assertion, scores and decreasedinternalizing behaviors, hyperactivity scores, andproblem behavior scores.

Implications of the StudySchool administrators are concerned with apositive and safe school environment. Peer rejec-tion has been linked to school violence. Giventhe demonstrated relationship between socialskills and school safety, schools are increasingly

seeking ways to help students develop positivesocial skills, both in school and in the community(National Association of School Psychologists,2002). Through proactive social instruction,children can acquire a sense of self-efFicacy, afeeling of being in control of their own emo-tional and interpersonal experiences (Saarni,1999).This fosters a positive self-image, whichcan overcome a learned helplessness attitudethat students with disabilities frequently develop.Emotionally well-regulated children are gener-ally more positive and pro-social and are able toform and contribute to friendships with theirpeers with and without disabilities.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SCHOOLSOCIAL WORKERSSchool social workers are important links be-tween the school, home, and community. Chil-dren with disabilities frequently have difficultiesin retaining and transferring knowledge acrosssettings and trainers. School social workers canmend this disconnect by informing parents ofskills that are taught in school and need to bepracticed at home. The Connecting with Others:Lessons for Teaching Social and Emotional Compe-tence program includes a section for parents, withhome activities to help transfer what has beentaught in school. School social workers are in aperfect position to review those activities andmodel them for parents to imitate. Lack of socialskills interferes with students' ability to benefitmaximally from their education, and in manycases these skills are not modeled in the home.Social workers can keep parents or caregiversinformed and help them with implementationof positive proactive strategies to change theinappropriate behaviors of the children.

Teachers in public schools are under pressureto teach their state's standards and to preparetheir students to pass their state's high-stakestests. Teaching social skills consumes time andis not a priority in most cases. In addition, nu-merous teachers do not feel qualified to teachin this area. School social workers can be a tre-mendous asset by assisting teachers in creatingsocial skills groups of student, teaching criticalsocial skills, and delivering proactive behavioralinterventions.

76 Children & Schools VOLUME 31, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2009

Limitations of the StudyThis study has several limitations. It was not con-sidered ethical to administer friendship assess-ment instruments or sociograms to the studentsbecause of the attention that would necessarilybe focused on the students with disabilities.Office discipline referrals were considered insome of the cases but were not applicable toall student participants. Therefore, this evalu-ation considered only the perceptions of thevarious teachers in assessing student growth. Afactor analytical approach was not used in thisstudy because of the ratio of students to items.Also, a control group was not used in the study.Further research is needed consisting of a largersample and a control group to measure socialskiOs growth resulting from the Connecting withOthers program.

Social skills training for students with dis-abilities has its weak aspects. Gresham and col-leagues (2001) recommended that the trainingwith this population be frequent and intense andlinked to the individual student's social deficit.Appropriate social behaviors will persist if theyare somehow immediately reinforced. A weak-ness is the failure of social skills acquisition todisplay sufficient generalization and long-lastingeffects. Still another problem is the assessmentof social skills training. The validity and reli-ability of rating scales frequently contribute tothe effects of the intervention. These measuresmay only detect short-term effects of socialcompetence. S

REFERENCESAlberti, M., & Emmons, M. (2001). Your perfect right:

Asscrtiveness and equality in your life and relationships(8th ed.). At.iscadero, CA: Impact.

Allen-Meares, P., Washington, R., & Welsh, B. (1996).Social work services in school (2nd ed.). Boston; Allyn& Bacon.

Berk, L. E. (2007). Development through the lifespan.Boston: Allyn & Bacon

Calloway, C. (1999). Promote friendship in the inclusivecla.ssroom |Electronic version]. Intervention in SchoolrtiirfC/m/c, 34, 176-177.

CASEL. (2003). Safe and sound: An educational leader guideto evidence-based social and emotional learning (SEL)prof^rams. Chicago: Author.

CASEL^(2008). Social and emotional learning (SEL) andstndent benefits: Implications for the safe schools/healthystudents core elements. Retrieved January 26,2009,from http://www.casel.org/downloads/EDC_CASELSELResearchBrief.pdf

Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy. (2002, November).Bringing evidence-driven progress to education: A recom-

mended strategy for the U.S. Department of Education.Retrieved April 22, 2005, from the Council forExcellence in Government Web site: http://excelgov.org/usermedia/images/uploads/PDFs/web_strategic_plan.pdf

Bpp, K. M. (2008). Outcome-based evaluation of a socialskills program using art therapy and group therapyfor children on the autism spectrum. Children &Schools, 30, 27-36.

Evans, E.T., & Richardson, R. C. (1989). Developingfriendship skills: Key to positive mainstreaming.fournal of Humanistic Education and Development, 21,138-151.

Freed, A. M. (1991). TA for tots. Rolling Hills, CA:Jalmar.Gresham, F., Sugai, G., & Horner, R. (2001). Interpreting

outcomes of social skills training for students withhigh-incidence disabilities. Exceptional Children, 67,331-344.

Meichenbaum, D. (1977). Cognitive behavior modification:An integrative approach. New York: Springer.

National Association of School Psychologists. (2002).Social skills: Promoting positive behavior, academic success,and school safety. Retrieved January 13, 2008, fromhttp://www.nasponliiie.org/resources/factsheets/socialskills_fs.aspx

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2008). Preventing drugabuse among children and adolescents: Examples of re-search-based drug abuse prevention programs. RetrievedJanuary 22, 2009, from http://\vww.drugabuse.gov/prevention/examples.html

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, PL. 107-110, 115Stat. 1425 (2002).

Prater, M.A.,Bruhl, S., & Serena, L. (1998). Acquiringsocial skills through cooperative learning andteacher-directed instruction. Remedial and SpecialEducation, 19, 160-172.

Richardson, R. (1996a). Connecting with others: Lessons forteaching social and emotional competence (grades K—2).Champaign, IL: Research Press.

Richardson, R. (1996b). Connecting with others: Lessons forteaching social and emotional competence (Crades 3—5).Champaign, IL: Research Press.

Roeser, R., Eccles,J., & SamerofF, A. (2000). School asa context of early adolescents'social-emotionaldevelopment: A summary of research findings.Elementary School Journat, 100, 443-471.

Rutherford, R., Mathur, S., & Quinn, M. (1998).Promoting social communication skills through co-operative learning and direct instruction. Educationand Treatment of Children, 21, 354-369.

Saarni, C. (1999). 77ie development of emotional competence.New York: Guilford Press.

Saenz, C. (2003). Friendships of students with disabili-ties [Dissertations/theses M.Ed. (040)]. Chicago:Northeastern Illinois University. (ERIC DocumentReproduction Service No. ED479982)

Schlitz, M. E., & Schlitz, S. C. (2001). Using direct instruc-tion and cooperative learning to improve the socialskills of students labeled as having moderate cognitivedelays (Master of Arts Action Research Project).Chicago: Saint Xavier University. (Eric DocumentReproduction Service No. ED456613)

Taylor, A., Sean-Peterson, C , McMurr.iy-Schwartz, P.,& Guillou,T. (2002). Soci.il skills interventions:Not just for students with special needs. YonngExceptional Children, 5(4), 19-26.

Wilde.J. {2007): Definitions for the No Child Left BehindAct of 2001.- Scientifically-based research. RetrievedJanuary 22, 2009, from the George WashingtonUniversity, National Clearinghouse for EnglishLanguage Acquisition and English Instruction

COOMBS RICHARDSON ET AL. / Character Education: Teaching Social and Emotional Competence 77

Educational Programs Web site: http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/resabout/Research_definitions.pdf

Rita Coombs Richardson, PhD, is a lecturer, School of Edu-cation, University ofSt.Thomas, Í2510 Boulder Creek Drive,Pearland,TX 77484;e-mail:[email protected], PhD, is professor, Department of EducationalAdministration and'Human Resource Development, TexasA&M University. Tse-Yang Huang, is assistant professor.Department of Education, National Hsinchu University ofEducation, Hsinchu City, Taiwan. Yi-Hsuan Lee, PhD, isassistant professor. Department of Business Administration,National Central University,fung-Li City, Taiwan.

Accepted December 11, 2008

NASW PRESS POLICY ONETHICAL BEHAVIOR

The NASW Press expects authors to ad-here to ethical standards for scholarship

as articulated in the NASW Code of Ethicsand Writing for the NASW Press: Informationfor Authors. These standards include actionssuch as ¡

• taking responsibility and credit only forwork they have actually performed

• honestly acknowledging the work ofothers

• submitting only original; work tojournals

• fully documenting their own and others'related work.

If possible breaches of ethical standards havebeen identified at the review or publicationprocess, the NASW Press may notify the au-thor and bring the ethics issue to the attentionof the appropriate professional body or otherauthority. Peer review confidentiality will notapply where there is evidence of plagiarism.

As reviewed and revised byNASW National Committee onInquiry (NCOI),May 30,1997

¡Approved by NASW Board ofDirectors, September 1997

Children & Schools VOLUME 31, NUMBER 2 APRIL 200978