Chapter 16 CIVIL RIGHTS: THE STRUGGLE FOR POLITICAL EQUALITY.

-

Upload

elwin-hall -

Category

Documents

-

view

233 -

download

1

Transcript of Chapter 16 CIVIL RIGHTS: THE STRUGGLE FOR POLITICAL EQUALITY.

Chapter 16Chapter 16

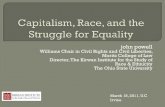

CIVIL RIGHTS: THE STRUGGLE FOR POLITICAL

EQUALITY

From Martin Luther King to From Martin Luther King to Louis FarrakhanLouis Farrakhan

The March on Washington (Aug. 28, 1963) Approximately 500,000 people converged on the

Lincoln Memorial to urge passage of the Civil Rights Act and to hear speeches by civil rights leaders.

The crowd was predominantly African American but included a substantial number of whites.

Most who were there believed that Americans were ready to accept a fully integrated society.

The mood was reflected by Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in his memorable “I Have a Dream” speech.

The Million Man March (October 1995) A little more than 30 years later, approximately

600,000 African-American men gathered in front of the U.S. Capitol Building in response to a call from Louis Farrakhan, the leader of the Nation of Islam.

Farrakhan said his Million Man March was designed to encourage self-reliance and responsibility among African-American men.

Women and white men were conspicuously absent on the speakers’ platform and in the crowd.

The climate for civil rights had changed in the years that separated these two events. The Million Man March reflected the uncertain

climate for civil rights in the mid-1990s compared to the more optimistic times of the mid-1960s.

The Million Man March, with its sometimes harsh separatist temper, reflected the racial polarization and isolation of race relations and civil rights policies in the 1990s.

Civil RightsCivil Rights

Civil Rights are government guarantees of political equality—the promise of equal treatment by government of all citizens and equal citizenship for all Americans.

Civil Rights Before the Civil Rights Before the Twentieth CenturyTwentieth Century

Initial absence of civil rights The word equality does not appear

in the Constitution. Americans in the late 18th and early

19th centuries seemed more interested in protecting individuals against government than in guaranteeing political rights through government.

Political Inequality of African Political Inequality of African Americans and Women Before Americans and Women Before the Civil Warthe Civil War

In the South, African Americans lived in slavery, with no rights at all.

In many places outside the South, African Americans were treated in a demeaning and inferior manner. Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)

No state allowed women to vote, few allowed them to sit on juries, and some even denied them the right to own property or enter into contracts.

Despite intimidation, many African Americans and women took an active role in fighting for their civil rights.

The Civil War AmendmentsThe Civil War Amendments Amendments Thirteen, Fourteen, and

Fifteen guaranteed essential political rights.

Undermining the effectiveness of the Civil War amendments: The Supreme Court transformed the constitutional

structure into a protection for property rights, but not for African Americans or women.

The privileges and immunities clause of the Fourteenth Amendment was rendered virtually meaningless by the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873).

The Slaughterhouse Cases (1873) The Court found that the privileges

and immunities clause protected only the rights of citizens of the United States as citizens.

The Court denied citizens protection against abuses by state government.

Equal protection soon lost all practical meaning.

Voting guarantees of the Fifteenth Amendment were rendered ineffective by a variety devices invented to prevent African Americans from voting in the former states of the Confederacy.

Poll tax Literacy tests White primaries

Women and the Fifteenth Women and the Fifteenth AmendmentAmendment

Politically active women turned their attention to winning the vote for women when they were excluded from the Fifteenth Amendment.

Women abandoned legal challenges after the Supreme Court decided that women’s suffrage was not covered in the citizenship guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment. Minor v. Happersett (1874)

The women’s suffrage movement focused on exerting political pressures.

The women’s suffrage movement finally led to ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

The Contemporary The Contemporary Status of Civil RightsStatus of Civil Rights

Civil rights for racial minorities Two basic issues have dominated the

story of the extension of civil rights since the mid-1960s:

Ending legal discrimination, separation, and exclusion

Debate over affirmative actions to rectify past wrongs

The End of Separate The End of Separate but Equalbut Equal

In 1944, the Supreme Court declared that race was a suspect classification that demanded strict scrutiny.

Despite strict scrutiny, the Court permitted the internment of Japanese Americans without any due process. (Korematsu v. United States, 1944).

Separate but equal overturned Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954)

Massive resistance to racial progress in the South Not much was accomplished until the President and

Congress backed up the Justices with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Today’s StandardsToday’s Standards The main doctrine on discrimination at

the present time is clear. Any use of race in law or government

regulations will trigger strict scrutiny from the courts.

Government can defend its acts under strict scrutiny only if it can produce a compelling government interest for which the act in question is a necessary means.

Few laws survive this challenge.

These legal protections do not mean that racial discrimination has disappeared from the US 1/3 of African- Americans and 1/5 of Latino and

Asian men report experiences of job discrimination. Overwhelming majorities of African Americans,

Latinos, and Asians say they have been subject to poor service in stores and restaurants because of their race, and have had disparaging remarks directed at them.

All minorities report bad experiences with racial profiling.

Affirmative ActionAffirmative Action The issues are not so clear with regard to government

actions that favor racial minorities in affirmative action programs designed to redress past injustices.

In Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), the Court prohibited the use of racial quotas by university admissions committees but later permitted the use of race as a factor in hiring or admissions.

More recently, the Court has said that programs that narrowly redress specific violations will be upheld but that broader affirmative action programs that address societal racism will not.

Civil Rights for WomenCivil Rights for Women

The Warren Court (1953-1969) did not significantly advance the cause of women’s rights.

The Burger Court (1969-1986) had to decide whether to apply ordinary scrutiny or strict scrutiny to sex discrimination cases. The justices felt that strict scrutiny would endanger

traditional sex roles while use of ordinary scrutiny would allow blatant sex discrimination to survive.

Civil rights for women is still more a subject for the political process than for the courts.

Abortion RightsAbortion Rights Roe v. Wade (1973) transformed abortion from

a legislative issue into a constitutional issue and from a matter of policy into a matter of rights. Disapproval of abortion decreased and discussion of

abortion increased during the 1960s. Justice Harry Blackmun’s opinion for the majority

prohibited states from interfering with a woman’s decision to have an abortion in the first two trimesters of her pregnancy.

Justice Blackmun based his opinion on the right to privacy (through the Ninth and Fourteenth Amendments).

Pro-life groups mobilized after Pro-life groups mobilized after

the the RoeRoe decision decision.. The Court eventually responded to anti-

abortion politics by deciding two cases: Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989) Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992).

The Court gave considerable latitude to the states to restrict abortions, but the majority affirmed its support for the basic principles of Roe.

Abortion has been a dominant issue in recent confirmations of judges and justices.

Sexual HarassmentSexual Harassment In 1980, the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission (EEOC) ruled that making sexual activity a condition of employment or promotion violates the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

The Supreme Court took a major step in further defining sexual harassment. Workers did not have to prove that offensive actions

made them unable to do their jobs or caused them psychological harm, only that the work environment was hostile or abusive.

Broadening the Civil Broadening the Civil Rights UmbrellaRights Umbrella

The elderly and the disabled Several federal and state laws now bar

mandatory retirement, and the courts have begun to strike down hiring practices based on age unless a compelling reason can be demonstrated.

Disabled Americans have won some notable victories, including passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

Gays and Lesbians Efforts to secure constitutional rights for

gays and lesbians illustrate political exertions in the face of governmental wavering.

The struggle for gay and lesbian rights will remain an important part of the American political agenda for a long time to come, with the eventual outcome very much in doubt.

Civil Rights and Civil Rights and DemocracyDemocracy

Political equality is one of the three pillars of democracy, equal in importance to popular sovereignty and political liberty. Political equality did not have a very high priority for

much of our history. The advance of civil rights protections since the end

of World War II has enriched American democracy because it has helped extend political equality.

Many areas of American life remain highly unequal and unrepresentative, but the attainment of formal political equality is real.