chaos theory- Project Muse

Transcript of chaos theory- Project Muse

PhilosoPhy, Psychiatry, Psychology

This issue is provided by The Johns Hopkins University Press Journals Division and powered by Project MUSE

Terms and Conditions of Use Thank you for purchasing this Electronic J-Issue from the Journals Division of the Johns Hopkins University Press. We ask that you respect the rights of the copyright holder by adhering to the following usage guidelines: This issue is for your personal, noncommercial use only. Individual articles from this JIssue may be printed and stored on you personal computer. You may not redistribute, resell, or license any part of the issue. You may not post any part of the issue on any web site without the written permission of the copyright holder. You may not alter or transform the content in any manner that would violate the rights of the copyright holder. Sharing of personal account information, logins, and passwords is not permitted.

WYLLIE / LIVED TIME AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

173

Lived Time and PsychopathologyMartin Wyllie

ABSTRACT: Some psychopathologic experiences have as one of their structural aspects the experience of restructured temporality. The general argument is that one of the universal microstructures of experience, namely, lived time offers a particular perspective relevant to certain psychopathologic experiences. Lived time is connected with the experience of the embodied human subject as being driven and directed towards the world in terms of bodily potentiality and capability. The dialectical relationship between the embodied human subject and the world results in a sense of lived time (personal time), a lived time that is intimately synchronized with the time of others (intersubjective time). Some experiences of acute suffering, and in particular acute melancholic suffering, can dramatically alter the temporal microstructure of experience to the extent that personal lived time becomes disordered. Normally, past and future withdraw on their own according with their nature of not being. The future is characterized as openness to change and movement. The absence of this openness is the closing of the future; without this openness, the future appears static and deterministic. When the future is experienced as static, then one longer has the possibility of things getting better, nor does one have any possibility of relinquishing or escaping from the past because a static future does not allow openness to change and movement. In short, both past and future become static. With the presence of melancholic suffering and the absence of temporal movement, a sense of hopelessness may arise in the individual because suffering without temporal movement becomes, from the sufferers perspective, eternal suffering. KEYWORDS: lived time, melancholia, activity, intersubjectivity, dead time, synchronization, temporality

I

I am concerned with a phenomenological description of lived time, simply, what it is like to experience lived time. The paper is concerned with human experience and how ones sense of lived time may become disordered during certain types of experience characterized as psychopathologic. These distortions in lived time are reported by some subjects as follows: Its the most terrible outlook Ive ever had to look to. Its all perpetual. Ive got to suffer perpetually (Lewis 1967, 4); [t]here is no future, just now (Sims 1995, 68). In these reports, one can understand what is being said, but, perhaps a little paradoxically, it is difficult to know what is meant. Researchers have attempted to describe these reported experiences from phenomenological, clinical, and experimental perspectives. Evidence for these types of experiences has been obtained by the following researchers: Thomas Fuchs (2001), Jrme Pore (2001), Christian Kupke (2000), T. Kitamura and R. Kumar (1982), Hubertus Tellenbach (1980), R. A. Wyrick and L.C. Wyrick (1977), Eugne Minkowski (1970), and A. Lewis (1967). These researchers have attempted to establish and describe what is meant by distortions in lived time during certain types of human experience that I characterize generally as melancholic states. It is important to note that I only consider these distortions not in terms of causing melancholic states, but simply as a phenomenological aspect of some melancholic states. Also,

N THIS PAPER,

2006 by The Johns Hopkins University Press

174 PPP / VOL. 12, NO. 3 / SEPTEMBER 2005

within this paper I discuss melancholia rather than depression. I use melancholia as a general term that subsumes the technical and nontechnical uses of the terms major depressive disorder, depression, bipolar, unipolar, and the various closely aligned subtypes of major depressive disorder used in psychiatric classifications. The main focus of this paper is an attempt to develop a phenomenological description of lived time and how distortions of lived time may occur. Within this context, phenomenology is conceived as a methodical effort to describe the universal microstructures of lived experience and these microstructures are found to be: embodiment, lived space, lived time, and intersubjectivity. Moreover, phenomenology analyzes the way people constitute their reality in a meaningful way. Within the constitution of meaningful experience, one can, on analysis, identify the critical points where the constitution of a meaningful mode of being in the world is exposed and open to distortions that become discernible as psychiatric conditions. By analyzing the structures of experience phenomenology provides a methodological framework for describing and understanding disturbances experienced in mental disorders. Lived time is a key component of human experience because persons as a whole are beings with emotions, values and purposes, and (importantly) they are temporal beings, beings who interact with their worlds in these ways over time (Matthews 2002, 60). Human beings attempt to describe aspects of their experience of lived time by using some of the following commonly used phrases: time just flew by, it seemed to go on forever, when we are apart it seems like an eternity, and so on. MerleauPonty observes that time is not a datum of consciousness, and demands much more precision when he states that consciousness unfolds or constitutes time (1962, 414). In this context, unfolds has to be understood in the way that dynamic processes unfold. In short, the way a process might simply unfold by running its course. For example, the processes of hunger and how these might be experienced and satiated and how there is a lived time aspect to these

experiences. Lived time is the experience of change as aligned to bodily activity and has no content in and of itself as it is the exchanging of one experience for another. This means that lived time is the present awareness one has of movement from one experience to the next which is brought about by ones bodily activity within a particular context. Lived time unfolds through the processes of bodily activity and this implies that our sense of lived time is aligned with the intentional and teleological processes of life. The experience of the present is an awareness of the dialectical and dynamic changing nature of experience through bodily activity. Lived time is a situational sensing of experienced time. For example, a dull meeting lasting only sixty minutes clock time might be reported by an attendee as having gone on forever whereas a dinner with a loved one lasting several hours seemed to fly by. These are two examples in which lived time respectively slows down or speeds up according to ones situational context. Having introduced the concept of lived time, in the next section I focus on developing a progressively more finegrained phenomenological description of lived time.

Lived timeLived time is not simply an endless random series of now moments lacking unity or coherence. Now in lived time is a unity of the past, present, and future, and is more than simply a succession because the immediate no-more, present, and yet-to-come are ordinarily never sharply separated. The fact of our immediate experience is what James called metaphorically the saddle-back of the present (1890, 609, 631), a present with a certain variable breadth of its own. Lived moments of time are not only based on the very last moment experienced, for experience is constituted by the whole set of moments, implying that the boundaries between present, past, and future are not strictly demarcated. In addition, the present has the past as its source, just as the future emerges from this present. There is implied within this description of lived time a sense of direction. Direction in

WYLLIE / LIVED TIME AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

175

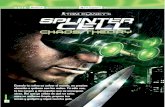

FIGURE 1. CAN BE SEEN EITHER AS A PLAN-VIEW OF A PYRAMID OR AS A CORRIDOR.

this context is activity toward the future; activity engaged in now has within itself a view toward its own completion. In short, lived time is what marks changes in our experience in relation to what delineates and terminates a particular experience. Experience is ordered by before/after relationships; simply, experience is temporal. Consider how the following example gives a sense of how bodily activity is connected with lived time. Notice the shifting of aspect perception between a plan view of a pyramid or corridor has a certain depth in time and this is variable due to ones ability to switch between these aspects. There is a sense in which a particular aspect is now (now it is a pyramid) and a shift to another aspect is another now (now it is a corridor) and these nows vary in depth depending on the activity of seeing either a pyramid or a corridor. In Figure 1, it is clear there are two distinct visual experiences, one of a corridor and one of a pyramid, both of which have a duration with a relative dependence on the content of the views. Even in the simple Figure 1 example, one should become aware of the experience as a temporal experience that has both duration and flow (first it is a pyramid which has a depthduration in time, and then it flows from this into the view of a corridor, again with duration in time). Ones experience in the world is one of the dynamic changing nature of experience resulting in the complementary sensing of lived time. Identifying the figure as a pyramid has a unity that first appears as now. That now is replaced with another now when it appears as a corridor. The appearance of these temporal shifts is aligned with the activity of something happening. That is to say, lived time is our experience of things happening and this correlates lived time with the activity of the

embodied human subject which in turn results in a bias toward the future. Everyone portends an immediate future; as Minkowski observes: our life is essentially orientated toward the future (1970, 80). This is because the past is closer to knowledge than it is to the acts of living and the future is the expansive world-view that includes the productivity of past acts of living. This bias toward the future is imposed by the embodied subjects asymmetry and this is a result of the embodied subject having frontback asymmetry in terms of its physicality. For example, the eyes are forward looking, the arms of able-bodied individuals function toward that which is in front of one, and walking is generally easier in a forward direction. The body itself sets up a bias toward that which is in front and not toward that which is behind and this is what is meant by frontback asymmetry. This parallels temporalitys asymmetry characterized as the future being necessarily open (in front of/front) and the past being apparently closed (behind/back). One moves forward in lived space, even if walking backwards, and one also moves forward in lived time, even if remembering past events. In short, the embodied subject is itself a spatiotemporal field orientated to what is in front and directed toward the things yet to come. Lived time is our experience of things happening and this correlates lived time with the activity of the embodied subject. This is a dialectic conception of lived time and, if correct, one in eliminating activity in the world also eliminates lived time. Conversely, the restructuring of lived time results in restructured activity, which is precisely what happens in certain melancholic experiences. Changes in lived time have been observed and recorded phenomenologically, clinically, and experientially (Fuchs 2001; Kitamura and Kumar 1982; Kupke 2000; Lewis 1967; Wyrick and Wyrick 1977). Generally, one observes that passivity slows the course of lived time. In eliminating activity temporality is also eliminated and the experience of stagnation occurs, in particular, melancholic situations can slow [my emphasis] the course of existence and bring it to the verge of stagnation (Tellenbach 1980, 148).

176 PPP / VOL. 12, NO. 3 / SEPTEMBER 2005

In an attempt to describe this stagnation, it is necessary to go a little deeper into the structure of lived time by introducing some of the structural aspects of lived time; namely not-yet and nomore. The embodied subject experiences lived time as shortages: as a not-yet (future) and nomore (past); both not-yet and no-more are absences synthesized into the present. It is the absence of the present-just-past (no-more) and the absence of the immediate present-yet-to-come (not-yet) that are synthesized into the present. This is not a holding onto the past or an anticipation of the future, but an active presentation of the absence of both that is synthesized into the present. It is not the past in the present, it would not then be the past, but the absence of the past that is integrated in the present. It is not that the future exists in the present, but the absence of the future that is integrated into the present. One should note, however, there is no symmetry between future and past. The future is not an expectation that is understood as predictable. Rather, the future is more like an openness or an appetite for making the indeterminate future determinatepresent. In contrast, the past has the structure of a continuum and past moments cannot be retroactively modified. Furthermore, past moments set some of the boundary conditions for the present that in turn influence the future; what someone has been in the past provides the reasons for her present actions, which are directed toward the future. Nonetheless, despite this asymmetry one can economically characterize the future and the past as absences in terms of what will be-no-more and what is yet-to-be, both of which are absent now. To use Husserls example, one can think of this in terms of listening to a melody (1964, 41). At any point in listening to the melody, there is the absence of the notes previously heard and the absence of the notes not yet heard. If the previous notes were somehow retained unmodified in the present, then one would be unable to hear the melody at all. Past notes cannot be in the present, because they would not then be past. Also, future notes are anticipated not in the way one would hear the notes, otherwise they would not be future notes. It is the absence of the notes that is experienced

in both directions (cf. James 1890, 609, 631). The past is synthesized in the present in terms of an absence and the future is also synthesized in the present in terms of an absence. Ordinarily, past and future withdraw on their own according with their nature of not being. And this is relevant because suffering loads the present with the immediate-past and immediatefuture, which is contrary to their nature of notbeing. The crucial fact about suffering and pain is their presentness; pain-here-now is so incontestably present that having pain or suffering could be thought of as an example of absolute certainty. For the individual experiencing intense pain or suffering, the pain or suffering is overwhelming and emphatically present now. Specifically, this pain-here-now produced by pain brings together no-more, yet-to-come, and now. This now is temporally disordered suffering because there is no longer an absence of no-more and yet-to-come. In severe pain and in some cases of melancholic suffering, all there is is the immediate self-negating suffering of painhere-now. Suffering in this context is known by its intensity and in its characteristic ability to reduce both past and future to nothing. More accurately suffering presents the sufferer with an unchanging past and an unchanging future. Both future and past are no longer absent; they are now because of the nature of suffering present in terms of a recapitulation of the suffering moment. One suffering moment begins to resemble the next suffering moment and the next and so on until the suffering begins to ease and temporal movement is reestablished. The present ought to in accordance with its nature contain the progressive absence of previously experienced nows, and both future and past collapse into the present; the present is loaded with the absences of what has immediately preceded it and with what may follow it. The future is in the present as a systematic array of potentiality and open determinations. The past is also constituted in the present as previously experienced determinations and engagements, thus allowing one to further articulate and/or rearticulate past events through the movement of ones unfolding life. The present is grounded in past

WYLLIE / LIVED TIME AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

177

determinations, engagements, experiences, and disappointments, which entail their future direction. In short, the present engagement with the things of the world preserves the past by carrying forward and developing its potentialities. Lived time is simply the synthesis of the now-just-past, present, and now-yet-to-come. The present already announce[s] itself as what will soon be past, we must feel the pressure upon it of a future intent on dispossessing it; in short the course of time must be primarily not only the passing of present to past, but also that of the future to the present (Merleau-Ponty 1962, 414). The future is a brooding presence (Merleau-Ponty 1962, 411) toward which the embodied subject moves and is characterized as an openness to change. Here the future is experienced by the embodied subject as a lack that is never normally satiated because there is always another open moment that itself requires nourishment by another, and so on. This implies the absence of every future moment that will evolve from a generality of future events into a specific present. This slowly emerging description of lived time becomes even more complex because lived time also has a social or intersubjective dimension.

Intersubjective TimeThe embodied human subject necessarily perceives the world from a particular place in space and time and the embodied human subject is always already in an intersubjective world. As observed by Matthews, [t]he world that we perceive is not timeless, but present; our involvement with it is necessarily permeated with our habits of perception derived from our past experience and encoded in our bodies (2002, 92). Merleau-Ponty argues that my living present opens upon a past which I nevertheless am no longer living through [no-more], and on a future which I do not yet live [not-yet], and perhaps never shall, it can also open on to temporalities outside my living experience and acquire a social horizon, with the result that my world is expanded to the dimensions of that collective history which my private existence takes up and carries forward (1962, 433). Here lived time gains a

social dimension and this is important within the field of psychopathology because lived time is a fundamental aspect of ones world and is important for two reasons: (i) our being-in-the-world allows for intersubjective time (being-with-others) to play an integral part in harmonizing ones life; and (ii) past, present, and future can become restructured in certain experiences. Our human being in the world allows for intersubjective time (being-with) to play an integral part in harmonizing ones world because every society, like any individual, has its own past, present, and future. The dynamic of this everyday contact with others entails a habitual dialectic synchronization (cf. Fuchs 2001). Personal lived time and its reference to intersubjective time are naturally bound together in a dialectic relation of tripartite time, namely, past, present, and future. Thus from the beginning, the microdynamics of everyday contact imply a habitual synchronization. They bring about a basic feeling of being in accord with the time of the others, and living with them in the same, intersubjective time (Fuchs 2001, 183). It is in this sense that both personal lived time and intersubjective time are either in accord or in discord with each other. This being the case, the foundations for restructured temporality are laid because certain experiences can restructure and in some cases disorder ones sense of temporal movement and direction. Lived time is not solipsistic, but primarily a lived synchronicity with the environment and with others. It is only from periodical desynchronizationsi.e. states of shortage, need, incoherence, insufficiency, guilt, or separationthat the experienced time of the not-yet or no-more results (2001, p. 185). It is not, according to Fuchs, synchronization that brings about the awareness of lived time; on the contrary, this occurs from disturbances caused by biological and/or psychosocial factors. The processes of personal time and intersubjective time normally unfold more or less together; intersubjective and personal time influence each other in an intimate dialectic exchange. This results in a sense of being in lived synchronisation (Minkowski 1970, 65) with others, a sense of being in tune with the time of others.

178 PPP / VOL. 12, NO. 3 / SEPTEMBER 2005

An ordinary example that may give a fairly modest sense of what it may be like to be decoupled from the time of others is arriving late for a meeting and the difficulties one has of contributing to the meeting because the discussion has already started. In this example, there is a sense of being left behind; one is not in synch with the time of others. One cannot, in this situation, open toward the future unfolding of the meeting, so in a sense, rather than projecting forward into the open future, the uncertain closed future advances toward the delayed individual. The living present of an individual opens into intersubjective time and acquires a socially significant dimension, thus expanding the individuals worldview, a view that is taken up, fused with intersubjective time and carried forward in the personal present. As discussed, activity or the lack of activity correlates with ones sense of lived time. For example, inactivity makes one aware of the passage of time and this can manifest itself as boredom. When bored, one begins to sense the stagnation of ones personal lived time against the dynamic background of intersubjective time. Movement and activity give the measure of personal lived time, which shows up against intersubjective time. The habitual ways of human being in the world implies, from early childhood, a synchronization with the dialectic rhythms of life, for example, in terms of environmental timings, including biological patterns: wakesleep cycles, diurnal hormone levels, circadian rhythms; planetary configurations: daily solarlunar cycles and seasonal variations; and, in terms of ones complex intersubjective life, family living patterns, timetables, working practices, and social protocols. From the very start our human being in the world is in accord with the time of others and a living with them in intersubjective time. These rhythmic processes of life are not simply passive reflexive reactions to environmental changes because the human being actively looks for and discovers the dialectical rhythms surrounding them to attune themselves to the influences of others. Simply, the individual is strongly influenced by their surrounding environment. More complex conjunctions of socioen-

vironmental rhythms influence the individual to such an extent one could argue such rhythms are essential to ones well human being in the world. For example, during certain melancholic episodes, the individual may become disengaged from intersubjective time and live in their own personal time while intersubjective time passes the individual by. In some temporally distorted experiences, there is no future and this has the effect of fixing the past. Intersubjective time still flows and measured time still has duration and lapses. However, lived time is experienced as a slowing down or stopping of personal lived time because it is experienced and/or measured against intersubjective time. Fuchs calls this the loss of affect attunement and observes that [t]he affect attunement with others fails. This is connected to the inability to participate emotionally in other persons or things, to be attracted or affected by them. Painfully, the patient experiences his rigidity in contrast to the movements of life going on in his environment (2001, 185). Kupke observes that in some melancholic states, [t]he melancholical subject is suffering from a break between its own, subjective and an extraneous objective time, and this break appears as a falling behind, as slowing down, or even as a total standstill of subjective time [ . . . there] is a crack or a split between them, and if this is the case the foundations of insanity are laid (2000, 4). These cracks or splits become apparent because human activity tends toward the future a future that includes intersubjective time; in the suspension of activity or radical passivity, lived time is reversed because the future comes toward the inactive individual who simply waits for the future to become present. This reverses temporality because a human beings engagement in meaningful activity is necessarily forwardfuture looking. Human beings are primarily actively directed toward the future, that is to say, their function is goal directed intentionality: a being after something or appetitive tension (Fuchs 2001, 181). The absence of engagement toward the future may in some cases result in an impoverished present and past. For example, in certain experiences, such as the loss of a loved one, the

WYLLIE / LIVED TIME AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

179

FIGURE 2.

individual may become desynchronized from intersubjective time because attention is directed toward the time of no-more; as intersubjective time passes, a preoccupation with the loss comes and redirects the individual back into the past. This can be characterized as a separation from intersubjective time; a separation from the others with whom one should be in synch. Normally, our experience includes as part of our own progressing the time of others; in overabsorption with the past, one reverses the normal direction of lived temporality; so instead of the normal direction of lived temporality (pastpresentfuture; Figure 2.a), the past-obsessed individuals personal lived time becomes configured as presentpast (Figure 2.b). In certain experiences, perhaps in relation to intense regret, rather than the person projecting (2.a Present ! Future) into the future, the future rushes toward the individual (2.b Present ! Future) because the regretful person will not relinquish the past. For such a person, the present always fails in comparison to the past. The person cannot move on because meaningful activity is solely defined in the past tense. In this way, a suffering future is constructed out of the disappointments and failures of the past. In this example, the individual suspends activity as one can only live in the present by projecting forward into the open future. The suspension of futureorientated activity may result in the experience

of [t]ime as passing by, the time of no-more, comes to our consciousness in interruptions of the stream of life, mainly in separations from the others with whom our life is in synchrony. While normally the movements and alterations of things or men are included in our own progressing, their direction is now reversed. They advance towards us and pass on by, while we cannot take part in their sequence any more (Fuchs 2001, 177). Here, Fuchs gives a sense in which the future is left in the wake (cf. fig. 2.b) of the past insofar as it is not lived; rather than movement toward the future in the present, one lives the dead past in the present and it is dead because one requires an open future to relinquish and/or relive the past. The lived time of others now advances toward the past-obsessed individual and simply passes them by. In short, one is out of sync with others and lags behind the changes occurring in the world, thus preventing intersubjective time from enriching ones worldview. Intersubjective time connects us with the world of others; it is one of the threads that constitute ones human being in the world. One of these threads is lived time and slackening the intentional threads which attach us to the world [ . . . ] brings them to notice (Merleau-Ponty 1962, xiii) and this slackening of the intentional threads produces a sense of dead time. A deep and profound sense of boredom may arise as one begins to notice the passage of time. Time,

180 PPP / VOL. 12, NO. 3 / SEPTEMBER 2005

despite its apparently abstract character, plays a vital and very personal part in our lives.

Dead TimeWhen I lie talking all alone, Recounting what I have ill done, My thoughts on me then tyrannise, Fear and sorrow me surprise, Whether I tarry still or go, Methinks the time moves very slow. Robert Burton The Anatomy of Melancholia (1651).

Distortions in lived time, as mentioned, are observed in certain pathologic states, and these disturbances have been experimentally verified (Kitamura and Kumar 1982; Lewis 1967; Wyrick and Wyrick 1977). An aspect of certain melancholic experiences include problems with lived time. Some melancholic persons appear to experience a dilation of time. For example, they estimate lived time intervals to be longer than the actual objectively measured time (Kitamura and Kumar 1982). One can deploy and develop these descriptions of lived time more specifically in relation to some types of melancholic experiences; as Fuchs observes: [t]he depressed [melancholic] person, so to speak, lives time no longer as his own; instead it comes upon him from in front and over-rides him (2001, 179; cf. Figure 2.b). The future is the most important temporal modality when considering melancholia because the future is experienced as an expansive world-view that includes the productivity of past acts of living; the past, however, is closer to knowledge than it is to the acts of living. The absence of openness onto the future is the closing of the future because without this openness onto the now-yet-to-come the future appears static and deterministic. The future is normally experienced as an open absence in the present; however, some experiences introduce the future as a static presence in the present; in these experiences the past no longer allows the possibility of escape because the future no longer allows for openness to change and movement. This is important in melancholic states because every situation normally

contains the possibility of change; if the future is closed, the possibility of change is denied because there is no possibility of change without a future in which to make that change. The future gets blocked in some melancholic states by the negative attribution that things will not get any better. This conviction dominates the persons outlook, rendering it deterministic. Chance and contingency no longer play a role in the melancholic persons life. Without activity, temporality stops because it is activity that produces lived time. This is illustrated by one of Sims subjects when they report: [t]here is no future, just now (1995, 68) and this now is a now in which the future is no longer absent, but present in the sense of a recapitulation of the present. In ascertaining being ill from the start the melancholic grasps his past and returns to his future in ascertaining that his life will go on so up to the end (Kupke 2000, unpublished). Ordinarily, experience is directed by the coming and going of events in the world. The appreciation of the movement of life in the world with the present becoming the past and the present leading to the future for which plans are made may be disturbed in melancholia. Engel describes this state as the affect of hopelessness (1967). Beck reports suicidal ideation was related to the subjects conceptualization of their situation as hopeless (1963). This view is echoed by Fraber (1968) and by Kobler and Scotland (1964), both concluding that hopelessness can be characterized as negative expectations about the future. The future is the dimension toward which hope is directed. Therefore, a closing off of the future may be attended by a loss of hope. A loss of hope in the future leads one to no longer expect any pleasure in the new or in the things one once took pleasure from, and one stops looking or not looking forward to things. The experience of hopelessness can produce a sense of endless suffering, so that suicide may be considered as one possible way of ending this perpetual suffering. Recurrent thoughts of suicide are a characteristic of some melancholic states and even with the best possible care, a small proportion of depressed patients are likely to die by suicide (American Psychiatric Association 1993, p.21).

WYLLIE / LIVED TIME AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

181

The closing of the future may be a contributing factor in the frequency and intensity of suicidal ideation. People are continually projecting into the future. This aspect of lived time can be characterized as a type of appetitive pressure for there to be a future (a next moment, and the next, and so on), and also an appetitive pressure to abolish the past in terms of moving on from the past. Characterized in this way temporality is a field of shortage, which is ignored only insofar as ones needs are not met, because one is never satisfied by the next moment as each moment in turn generates the potentiality of the next yet-tocome. This need is always now, as the present is always at least partially constituted by openness onto the future. It is not that the future is in the present; the future as such cannot be in the present. What is in the present is openness onto the future, and it is this openness that has direction and intentionality toward closure and fulfillment. In short, as the future closes the past and present become static. In his section on the Disintegration of the Notion of Time, one of Minkowskis patients reports the following in relation to time: I feel the desire to act, but this produces an opposite reaction to that of normal people; the phenomenon of stopping surges up and causes a complete discouragement. I have the feeling of the type that goes negatively in relation to time, I have the sensation of a negative void (1970, 333). Lived time is the sequential progression of life; lived time is a sensing of one event after the other, and this sense of time is central to the embodied subjects dialectic relationship with the world. Phenomenological disturbances of sensed time, although not always of great importance to the human being, are an indicator that something is going wrong. For example, melancholic depersonalization is accompanied by a serious disturbance of temporalization, a sense of inhibition of becoming (Kraus 1995, 202203). Even the most limited ability to separate events into past, present, and future; to estimate duration; and to place events in sequence appears to be necessary for intellectual processes to be carried out satisfactorily. Temporality as a modality

of personal experience can become disrupted in episodes of melancholia and this has been observed clinically (Byron 1992, 41; Fuchs 2001; Minkowski 1970, 332355), experimentally (Lewis 1967; also, Wyrick and Wyrick 1977), and phenomenologically: depressed individuals are significantly more likely to feel that time is passing more slowly than in control subjects (Kitamura and Kumar 1982). With an absence or decline in worldly activity an individuals sense of time is altered, resulting in a protraction, slowing, or noticing of temporal movement resulting in an impoverished now characterized as boredom. A loss of vital contact (Davidson 2001; Minkowski 1970) or a loss of affect attunement (Fuchs 2001, 185) with the world may result in activity drying up. Temporality needs activity, without which existence becomes mere existence characterized as an inability to conduct ones business in the world. This can be expressed as exposure to a formal empty generalized being and this being is the collapse of temporality and activity. This formal being is the supporting generalized anonymity at the core of living experience analogous to the support the skeleton affords the lived body. A sufferer attempts to report this collapse of temporality and activity resulting in mere being in the following quote: [o]nce I was a man, with a soul and a living body and now I am no more than a being [ . . . ] I now live on in eternity [ . . . ] for me time no longer passes [ . . . .] Everything is constantly beginning all over again (Merleau-Ponty 1962, 283). This eternal reoccurrence of lived time is in contrast to the dynamism of becoming, whereby an individuals human being is characterized as a gathering together of a life within a continuously changing temporal world. Becoming is a temporization that gathers together the daily activities of living into a single coherent human life under the orchestration of the embodied human subject. Becoming in this context simply means having temporality and this primarily entails the continuous interaction between a living being and its environment. There is here a syntony between the individual and its environment in which the individual preserves its becoming by way of drives,

182 PPP / VOL. 12, NO. 3 / SEPTEMBER 2005

needs, or goals of activity. Syntony alludes to the principle that allows us to vibrate in unison with the environment, while schizoidism, on the contrary, designates the faculty of detaching ourselves from that environment (Minkowski 1970, 73). Schizoidism occurs where there is a lack of syntony with ones world because one simply cannot become in a void. In contrast to a state of human becoming (syntony), mere being (schizoidism) can be viewed as a state of utter disconnection or desynchronization, which leaves the individual in an impossible state of existing in a void of pure formal being. The structure of temporality resulting from this is not the experience of temporality as such, but of a kind of negative eternity. One rare condition that powerfully demonstrates a sense of negative eternity is Cotard syndrome, in which nihilistic delusion brings the individual to a near state of being not in the world. One could characterize such experiences as a pure being, or to use Dr. Fuchs beautifully illustrative metaphor, which describes these types of experiences as black holes in the world of the living. The full-blown delusion of Cotard may come about in different kinds of disorder (e.g., as an organic delusion), but in relation to melancholia there is a difference of degree to less serious states of isolation and corresponding delusions. Significantly for a continuum approach to psychopathology Cotards syndrome has been associated with depressive symptoms (Baeza, Salv, and Bernardo 2000, 11912; Chainho et al. 1994, 433435; Fillastre et al. 1992, 6566; Hamon and Ginestet 1994, 425443; Ko 1989, 277278; Le Roux and Rochard 1986, 971985). Merleau-Ponty also makes reference to melancholia and his own observations suggest a link between melancholic states and nihilistic delusions: the most advanced states of melancholia, in which the patient settles in the realm of death and, so to speak, takes up his abode there (1962, 293). For those immortal persons suffering from advanced states of melancholia, their suffering may be unbearable and infinite, and it is unbearable because it is infinite. With the absence of temporal movement and the presence of suffering, suffering becomes perpetual suffering.

Perpetual suffering is suffering with a beginning but no end. Suffering is perpetual if it began, and in so beginning stops temporal movement. Suffering without temporality is suffering that will not end: time without its roots in a present and thence a past would no longer be time, but eternity (Merleau-Ponty 1962, 427). This relates to the quality of suffering in that restructured or disordered temporal suffering overwhelms the temporality normally inherent in ordinary suffering and every day life. Mourning is an example of ordinary suffering that is temporal; it arises, has extension, and diminishes. This allows the mourner to untie emotional bonds that do not correspond with the present anymore. A person who does not bear and live through this grief remains in asynchrony. In some cases of severe depression, the suffering is perpetual suffering, having no imaginable end. From a third-person perspective, one would say restructured temporal suffering; however, from the individuals first-person perspective, it is endless suffering. It is endless in the sense of having no imaginable end for the particular sufferer because without temporality the suffering appears to the individual to be unending suffering. As one of Lewiss patients reports: Its the most terrible outlook Ive ever had to look to. Its all perpetual. Ive got to suffer perpetually (1967, 4). The phenomenology of these types of pathologic experiences suggests in some cases the sufferer can no longer participate in the world and temporality is lost. The sufferer cannot project themselves into a future of events and there is therefore no sense of things getting better. The sufferer is biologically living, but the future appears dead in terms of fulfillment. In these cases, there is no future into which the sufferer can project into with the result that becoming and biological freedom cannot be accomplished. Here the future appears to be held in abeyance; and yet the sufferer experiences and appreciates this stopped future in the present because this stopped future is embedded in the present. Here now and yet-to-come are no longer moving apart from each other as is their being because they are bound to one another in suffering. With

WYLLIE / LIVED TIME AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

183

the future closed, the sufferers experience of the past also becomes disordered because the past can no longer be experienced as a horizon onto the open future. The past itself becomes fixed once and for all because it cannot be abolished by any future living, because the suffering present displaces the past and future and deprives the lived present of its value. The personal present in suffering is arrested or slowed down and this slowing down is measured as intersubjective time continues on its course. The present, enclosed between the faults of the past (negative attribution) and the noncompensatory future (future suffering) becomes impoverished and the course of time begins to slow down.

ConclusionDisturbances in lived time as described may be of little importance to a particular individual but may, nonetheless, be a useful indicator that something is going wrong. Clinicians frequently ask patients standard questions in relation to time. For example, what is the year, month, or day? (Mini Mental State Examination). Here, one is asking questions in relation to what time as opposed to asking questions in relation to changes in time. For example, one can ask the individual to estimate the duration of the Present State Examination or interview. Or, one could ask them to estimate the duration of a period of measured clock time. By asking such an apparently simply question, one may gain insight into the nature of a particular individuals suffering in terms of its intensity; it is my argument that intense suffering impacts how an individual senses lived time. It could be that questions relating to the duration of time could act as a diagnostic tool by measuring the severity of the individuals suffering. It also follows from the description given in this paper of lived time that such a description is open to falsification. This being the case, some aspects of the phenomenological description of lived time presented in this paper in relation to lived times duration can be empirically tested. The ability to falsify phenomenological descriptions is important because these descrip-

tions, if open to falsification, provide a bridging medium for interdisciplinary communication between psychiatry, psychology, neuroscience, and philosophy, thus making science more philosophical and philosophy more scientific. In short, phenomenological descriptions are important in any multidisciplinary approach to problem solving within the field of psychiatry, psychology, and neuroscience because each discipline, including phenomenology, complements and constrains the others by mutual instruction and illumination. It would be futile to just look at phenomenological findings in isolation from other disciplines. One where possible should attempt to accord and constrain such descriptions by constructing appropriate links between different disciplines. This would mean using methods that can provide data to the objective, empirically based descriptions to facilitate a more integrated position where neither methodologies have the casting vote and where each provides checks and balances against the other. Psychopathologic experience is in this paper is reconceptualized as a restructuring of the universal microstructures of experience, which support ones being in the world; namely: embodiment, lived space, lived time, and intersubjectivity. This perspective does not change what counts as pathology nor does it cast doubt on what have been successful ways of treating psychopathologic experiences; rather, it conceptualizes psychopathology in a different way. Certain psychopathologic experiences compromise ones sense of self and reality (cf. American Psychiatric Association 1994, 300.6 Depersonalization Disorder, pp. 488 490) because such experiences are all-pervasive ways of being in the world. Psychopathologic experience pervades both the higher level structures of experience (i.e., intentional object, directedness, meaning, context) and follows the constitution of ones being in the world down to the supporting microstructures of experience. Some psychopathologic experiences have as one of their structural aspects the experience of restructured temporality. Temporality is connected with the experience of the embodied human subject as being driven and directed toward the world in terms of bodily potentiality and capa-

184 PPP / VOL. 12, NO. 3 / SEPTEMBER 2005

bility. The dialectical relationship between the embodied human subject and the world results in a sense of lived time (personal time), a lived time that is intimately synchronized with the time of others (intersubjective time). Certain pathologic experiences so dramatically alter the temporal microstructure of experience that the individuals sense of personal lived time is restructured and/or disordered. In these circumstances, temporality may, as a result of the nature of suffering in terms of its overwhelming presence, fully deploy temporality; past, present, and future are no longer moving apart from one another. Normally, past and future withdraw on their own according with their nature of not being. The future is characterized phenomenologically as openness to change and movement. The absence of this openness is the closing of the future because without this openness onto the now-yet-to-come, the future appears static and deterministic. This sense of a deterministic and static future results in hopelessness and despair; without temporal movement the experience from the individuals first-person perspective becomes eternal suffering.

ReferencesAmerican Psychiatric Association. 1993. Practice Guideline for major depressive disorder in adults. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. . 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders fourth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Baeza, I., B. M. Salv, and Bernardo, M. 2000. Cotards syndrome in a young male bipolar. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 12, Winter:119120. Beck, A. T. 1963 Thinking and depression: I. Idiosyncratic content and depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 9:324333. Burton, R. 1651/1920. The anatomy of melancholia. London: G.Bell and Sons, Ltd. Byron, J. G. 1992. Pain as human experience. Berkeley: University of California Press. Chainho, J., J. Antnio, A. Paiva, and F. Reis. 1994. A case of Cotards delusion of negation. Acta Medicina Portugal 7, no. 78:433435. Davidson, L. 2001. The restoration of vital contact with reality: Minkowski, Sartre, and Joie de Vivre as a basis for recovery (unpublished manuscript).

Engel, G. L. 1967. A psychological setting of somatic diseases: The giving-up-given-up complex Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 60:553555. Fraber, M. 1968. Theory of suicide. New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1968. Fillastre, M., A. Fontaine, L. Depecker, and A. Degiovanni. 1992. 5 cases of Cotards syndrome in adolescents and young adults; symptoms of bipolar manic-depressive psychosis. Encephale 1:6566. Fuchs, T. 2001. Melancholia as a desynchronisation: Toward a psychopathology of interpersonal time. Psychopathology 34:179186. Hamon J. M., and D. Ginestet. 1994. Delusions of negation: 4 case reports. Annales Mdico-Psychologiques, Revue Psychiatrique (Paris) 152, no. 7:425430. Husserl, E. 1964. The phenomenology of internal time-consciousness. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. James, W. 1890. The works of William James: The principles of psychology. Volume 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Kitamura, T., and R. Kumar. 1982. Time passes slowly for patients with depressed state. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 68:1521. Kobler, A. L., and E. Scotland. 1964. The end of hope. London: Glencoe Free Press. Ko, S. M. 1989. Cotards syndrome-two case reports. Singapore Medical Journal 30, no. 3:277278. Kraus, A. 1995. Psychotherapy based on identity problems of depressives. American Journal of Psychotherapy 49, no. 2:197212. Kupke, C. 2000. Melancholy as time-structuring-disorder: A transdisciplinary approach. Text of a lecture for the 4th International Conference on Philosophy and Psychiatry Madness, Science and Society, Florence, August 2629, 2000; Section Psychopathology as the science of the suffering subject (original lecture title: The experience of another time in melancholical time-suffering; unpublished manuscript). Le Roux, A., and L. Rochard. 1986. Clinical update of global delusions of negation. Annales MdicoPsychologiques, Revue Psychiatrique (Paris) 144, no. 9:971985. Lewis, A. 1967. The experience of time in mental disorder. Inquires in Psychiatry. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Matthews, E. 2002. The philosophy of Merleau-Ponty. Chesham, UK: Acumen Publishing Limited. Merleau-Ponty, M. 1962. Phenomenology of perception, trans. C. Smith. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Minkowski, E. 1970. Lived time: Phenomenological and psychopathological studies. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

WYLLIE / LIVED TIME AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

185

Pore, J. 2001. Altration de la temporalit et emphase pathologique de la prsence dans la dpression. (unpublished) Sims, A. 1995. Symptoms in the mind: An introduction to descriptive psychopathology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

Tellenbach, H. 1980. Melancholy. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press. Wyrick, R. A., and L. C. Wyrick. 1977. Time experience during depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 14:14411443.

BROOME / SUFFERING AND ETERNAL RECURRENCE OF THE SAME

187

Suffering and Eternal Recurrence of the Same: The Neuroscience, Psychopathology, and Philosophy of TimeMatthew R. Broome

KEYWORDS: time, depression, phenomenology, neurophenomenology, cognitive neuroscience, psychopathology It is not easy to persuade him who suffers in one or other of these ways that he is not doomed to madness, or that he has not the mortal disease of brain which he fears he has. Notwithstanding that he has had previous attacks of the same kind from which he has recovered, he always declares the present attack to be different from and much worse than any former one and is sure he cannot possibly get well again. There is a feeling of eternity, no feeling of time, in relation to it. Of the worst grief at its worst there is always, when in health, a tacit or subconscious instinct of ending; but here an all-absorbing feeling of misery so usurps the being that there is no real succession of feelings and thoughts, no sense of time therefore, a sense only of an everlasting is and is to be [. . .]. To inspire a gleam of real hope in the gloom of melancholy is to initiate recovery; it is to plant a morrow in the midnight of its sorrow: to infix a distinct belief of recovery is almost to guarantee it. (Maudsley 1895/1979, 171172).

W

a very welcome addition to the phenomenological literature on depression. Or rather it is more than thatWyllie demonstrates in his analysis of temporality how phenomenology has genuine value in terms of both clinical understanding and providing hypotheses for testing in empirical research. The therapeutic and research benefits that can potentially be garnered from Wyllies paper demonstrate how much philosophy, and phenomenology more narrowly, can do for psychiatry. In this gloss on Wyllies paper, I briefly review the available information on the psychopathology of time in a variety of mental disorders, including depression. Second, I attempt to place Wyllies hypotheses about lived experience and melancholia in the context of recent work from cognitive science on the perception of time. Last, I discuss how the philosophy of time in the twentieth century may be of utility to psychiatrists both in understanding their patients and in researching the disorders.

YLLIES PAPER IS

2006 by The Johns Hopkins University Press

188 PPP / VOL. 12, NO. 3 / SEPTEMBER 2005

Psychopathology and TimeAlthough one often is struck by how a sense of time is distorted in patients with a variety of different mental illnesses, there has been little or no recent empirical work on these symptoms. There is a literature that relies on clinical anecdotes or case reports, but no clear data that either measure the frequency and prevalence of such symptoms in a given population, or any psychological data that seek to measure such distortions and relate them other elements of psychopathology. Wyllie offers a way of understanding melancholia holistically, rather than as a collection of atomistic symptoms and signs. That is, as a clinical entity cohered by the centrality of a disorder of the experience of lived time. Through an existence dominated by the present and past, the sufferer is experiencing a determinate future with a lack of hope of change, a disproportionate dwelling on the past and guilty recollections; thoughts of suicide may seem the only way to end such eternal anguish. From Wyllies analysis, one could construct the hypothesis that factors such as hopelessness and suicidal ideation may correlate with, and be at least partially caused by, a change in lived time. Such a hypothesis is eminently testable and further, if found to be the case, could provide evidence that may be of great use to cognitivebehavioral therapists in designing and refining psychological interventions that may be efficacious in depression. That such data do not exist may indicate that with operationalized criteria there comes a risk that clinicians may forget to listen to how their patients describe how their symptoms hang together in a rational and understandable manner. Cutting (1997) helpfully reviews the psychopathologic disorders of time. In addition to depressive illness, disorders in the sense of time can occur in dementia, delirium, schizophrenia, and mania (Cutting 1997). Cuttings own series of patients with depression demonstrated a slowing down of the passage of time, but also a disorientation for time and a speeding up of the passage of time (Cutting 1997).

At the very least, one can conclude from the experimental studies that an average depressive, in estimating duration, experiences time as moving twice as slowly as normal. In extreme cases time stood still or was idling or was even going backwards, not, as in schizophrenia, because of a qualitative transformation in time, but because of a quantitative slowing to the point of extinction and reversal. (Cutting 1997, 218)

Patients with schizophrenia, by contrast, may suffer an alteration in time sense that differs from the psychopathology of mood disorders. Time may stop, repeat itself, or be subject to a less-than-smooth progression (Cutting 1997).

Cognitive Science and the Perception of TimeThe work of Edelman has been used by cognitive scientists to think about how the brain synchronizes a wide variety of experiences and time to a unified whole that is in turn synchronized to that of the environment (Dawson 2004). Internal clocks function to bind the subpersonal systems together with those of the outside world. For example, the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus is thought to mark 24-hour cycles, the frontal cortex expectations of the future, and the hippocampi the past (Dawson 2004). Further, Descartes friend, the pineal gland may serve as an integrative transduction system, responsible for transducing neuroelectrical information about light into hormonal signals (Dawson 2004, 79). The hormone melatonin, from the pineal, carries the information about the amount of darkness to the organism and the pineal synthesizes oscillations of hormones, motor activity, affect, and other elements with the lightdark cycle (Dawson 2004). Such a synthesis may generate a linear internal clock, which is supplemented by a more cyclical clock corresponding to body temperature. Dawson, working within a representationalist cognitivism, suggests a system existing in the brain that is necessary for consciousness and personhood, and is intimately involved in the perception of time:For events to have a coherent flow that is ordinarily ascribed to consciousness, there must be brain structures which generate an internal model of the external

BROOME / SUFFERING AND ETERNAL RECURRENCE OF THE SAME

189

world in terms of time. Indeed, such structures are the hippocampus, amygdala, hypothalamus, reticular activating system, and the epithalamus (commonly called the pineal gland). These regions presumably provide a kind of background for predicting events and preparing consciousness to interpret incoming sensory-perceptual experience. (Dawson 2004, 83)

In contrast to models that posit time sense as being a discrete function, Ivry and Spencer (2004) argue that internal timing is not a unitary function but rather task specific. Reviewing imaging findings, Lewis and Miall (2003) suggest that different brain areas are implicated in the measurement of time depending on the interval to be measured, whether movement is used to define time, and the predictability of the unfolding of events (Lewis and Miall 2003). Others go further and argue that there may not be any dedicated timing system in the brain (Nobre and OReilly 2004). Drawing on data from Coull et al. (2004), they suggest that other systems in which timing is important but not primary are recruited when temporal judgments are required. Glicksohn (2001) criticizes dominant models from a phenomenological perspective. He acknowledges the intimate link between consciousness and the sense of time, but argues against the dominant models of cognitive timers and internal clocks in that they do not adequately capture the experience of time. Glicksohn (2001) emphasizes the strong interplay between attention, arousal, and time perception and seems to take as an assumption a modularization of cognitive functions and attention as a pool of resource that will be shared between cognitive timers and other cognitive modules; thus, the flow of time phenomenologically depends on attention level. Glicksohn writes:Assuming a common pool of attention, there is a trade-off between externally oriented and internally oriented attention. The more absorbed the subject becomes in his or her subjective experience (due to a predisposition for high absorption and/or via an experimental technique such as introspection or concentrative meditation), the slower time appears to be. Internal events seem to be flowing by in slow motion, as fewer subjective time units are accumulated (hypoarousal), each of which is larger in extent (hypoarousal). (2001, 9)

He proposes that as arousal increases, the number of subjective time units increases and with an increase in externally oriented attention the size of the subjective units decreases. Apparent duration of time is based on a product of these two factors and is thus correlated with arousal and inversely correlated with externally oriented attention (and hence, positively correlated with internally oriented attention; Glicksohn 2001). The example of concentrative meditation is used as a possible exemplar of a state where increased internally oriented attention is coupled with reduction in arousal. Such a state should thus demonstrate a decrease in the number of subjective time units and an increase in the duration of each unit.The flow of time thus becomes slower, and each frame can be inspected longer. Timelessness would then be the limiting case of a single extended frame packed with information. (Glicksohn 2001, 11)

Other examples of timeless states may include suffering and intense emotions, violence and danger, altered states of consciousness, and shock (Glicksohn 2001). Glicksohns account is powerful and when read in parallel with Wyllie, one could add melancholia to Glicksohns list of timeless states, where attention is focused internally on negative memories. Further, Glicksohn stresses how the experience of time is contingent on ones degree of immersion in the lived world. Alterations in time sense may be causally responsible in some cases of depression, or at least in the maintenance of the disorder. It may be worth reminding ourselves that there are efficacious treatments where we seek to trick a patients cognitive timer or internal clock. Both light boxes and sleep deprivation are potent ways to elevate a patients mood, and in someone with a bipolar illness may serve as a trigger to a manic episode. Thus, therapy provides some support for the hypothesis that an organisms sense of time may be of causal importance in the pathophysiology of depression.

190 PPP / VOL. 12, NO. 3 / SEPTEMBER 2005

The Relationship Between Phenomenology and Cognitive (Neuro)ScienceTraditionally, cognitive science has been linked with the philosophical position of functionalism and has acted independently of the physical level, namely the particular object in which cognition is instantiated. Mental states are thus multiply realizable and are identified in terms of causal or functional role in mediating between sensations and behavior (Bechtel, Abrahamsen, and Graham 1998; Flanagan 1991). With the advent of connectionism and cognitive neuroscience, functionally relevant neural circuits began to be discussed and in philosophy the advent of eliminative materialism may have had a role in the undermining of a materialneutral cognitive science (Bechtel et al. 1998). For cognitive science to be successful, it may required to be constrained by biology. Hence, contemporary cognitive neuroscience can be viewed as being constrained by the alleged truths of folk psychology from above and by truths about the nervous system from below. However, if one considers Wyllies use of Husserl and Merleau-Ponty and the utility of phenomenology in understanding mental illness, in parallel with the dominance of biological psychiatry, one can ask what phenomenology can add to, or how does it differ from, a fleshed-out cognitive neuroscience? It could be considered that neurophenomenology (Varela 1998) is a subtype of cognitive neuroscience, a field where cognition is studied as being constrained by data from neuroscience but the constraining data from psychology is that provided by phenomenology, and in particular the phenomenological reduction (Varela 1998). He puts it thus:The Working Hypothesis of Neurophenomenology: Phenomenological accounts of the structure of experience and their counterparts in cognitive science relate to each other through reciprocal constraints. (Varela 1998, 351)

that Varela seeks to use are not equivalent to natural experiencehe states that discipline and training are required to be able to generate and report phenomenological data. Such data may be descriptions of aspects of experience that were not available before (Varela 1998, 354). This may be fine for a neurophenomenology of normal experience, but for a neurophenomenology of psychopathology this would require our patients to be phenomenologists to be able to describe their experiences to the interviewer adequately and allow access to such data. If this were even practicable, would such data be generalizable to the nonphenomenologist cases clinicians more commonly encounter? Van Gelder (1999) and Varela (1999) both offer accounts of a naturalized phenomenology of temporality. There are similarities, but also differences. Van Gelder offers an account of time through cognitive science, independent of the medium in which such mechanisms may be instantiated, whereas Varela explicitly relates his account back to the nervous system. Both, however, agree that classical computationalist accounts are insufficient to explain the phenomenological data and use dynamical or connectionist models. For Van Gelder, protention is conceptualized as current, intending, future stages as future to some degree, as a continuous manifold, as finite and direct (1999, 263). Van Gelders account is compelling. Although it lacks a biological framework, it is based on a close and thoughtful reading of Husserl coupled with clarity and a model from which predictions can be drawn and hypotheses tested. Van Gelder suggests that his account of how temporality may be exhibited by dynamic systems is strikingly similar to Husserls accounts of time consciousnessthe difference lies in that whereas Husserls time consciousness requires an almost direct perception of past and future, Van Gelders dynamical model can intend, but not perceive, the past and future.

Thus, for Varela, there is an explicit assumption that phenomenological data do a better job as a top-down explanatory constraint, rather than other types of psychological data. The accounts

Time and Twentieth-Century PhilosophyWyllies excellent paper demonstrates how fruitful the work of Husserl and Merleau-Ponty

BROOME / SUFFERING AND ETERNAL RECURRENCE OF THE SAME

191

can be in the study of psychopathology, and in particular the perception of time in melancholia. Given the clear utility of phenomenology, are other traditions in twentieth-century philosophy as useful in thinking of our patients and their disorders of time? Turetzky (1998) presents an account of philosophys study of time. For the twentieth century, he suggests we can view philosophy as being divided into three distinct, but not necessarily isolated, strands. These he terms the analytic, phenomenological, and distaff. The distaff includes the work of Bergson and Deleuze. Analytic philosophy is very much centered around the legacy of the British idealist, McTaggart, and the contrast between static time and temporal becoming. McTaggart notoriously claimed that time was unreal and that nothing that exists can have the property of being in time (McTaggart 1908/1993; Turetzky 1998). Much of the Anglo-American metaphysics of time in the twentieth century has been devoted to exploring and criticizing this argument. However, for our purposes, we need not go into the esoterica of such arguments (but see Loux [2001] and Le Poidevin [2003] as good, clear introductions) but can focus on McTaggarts anticommonsensical conclusion. Presumably McTaggart did not act on his unusual belief, or else kept it to the philosophy study; however, some of our patients do. Patients with a severe depressive psychosis may develop Cotards syndrome, that as well as hypochondriacal delusions, may also contain nihilistic beliefs about the existence (or rather, the nonexistence) of certain things. Such patients may describe, as Wyllies sufferer of melancholia, a determinate, static, almost crystalline structure of time where there is no change. Others may state that they have no date of birth, have never been born, and will always be. Such an existence is almost divineeternal and unchanging, pure being (Wyllie 2005). In addition to a closing off of protention, such patients may also demonstrate a paucity of retentionthe past is denied, and the horror of the now, eternal, ever-present, and never-changing is all that there is. Such a patient may demonstrate a subtype of Cotards, which

we can perhaps christen as McTaggarts syndrome, where they do deny the existence of time and of change, and hold according delusional beliefs. Such a delusion can radically affect a patients rationality, and in contrast with others who may still be able to enter a discourse within normative bounds yet be psychotic (Broome 2004; Campbell 2001), such patients are almost impossible to interview. The very process of undertaking a psychiatric assessment, of eliciting a history, is rendered problematic. The experience is so very alien to the interviewer that shared systems of belief are inaccessible or simply not present. The proposition that has most concerned twentieth-century analytic philosophy would only be believed by someone, McTaggart aside, with a very severe, typically depressive, psychosis. An illness that included such bizarre beliefs would likely render communication with the patient, and phenomenological description of their symptoms, almost impossible. This contrasts with the more subtle problems of time and temporality that have preoccupied the phenomenological and distaff traditions.

Heidegger and Levinas on Husserls Account of TimeHusserls The Phenomenology of Internal Time-Consciousness (Husserl 1928/1999) is an influential phenomenological account of temporality. Husserl has two goalsto offer an account of the subjective passage of time but also to account for how we can encounter objects as temporal. However, this account was relatively early in Husserls own career, being based on an amended lecture course from 1905 compiled by Edith Stein, and published by Martin Heidegger in 1928 (Bernet, Kern, and Marbeck 1993; Dostal 1993). Other views on these problems by Husserl are present in his unpublished writings (Bernet et al. 1993; Zahavi 2003). With this proviso in mind, there have been two equally prominent views of temporality in the phenomenological literature: these are the accounts of Heidegger (1927/1962, 1979/1985; Dostal 1993) and Levinas (1947/1989; Bernet 2002). Heideggers account of temporality in Being and Time is wellknown and Husserl viewed it as altogether too

192 PPP / VOL. 12, NO. 3 / SEPTEMBER 2005

anthropological and relativistic. Dostal (1993) goes so far to suggest that Husserl encouraged the publication of his 1905 lecture by Stein and Heidegger in 1928 to remind the latter of his thinking on the topic after the publication of Being and Time. Wyllies use of Merleau-Ponty brings in Heideggerian notions that it is through practical engaged activity in the world that temporality and its disorders are made manifest. Levinas takes this a little further and explicitly links temporality with sociality. Husserl uses as his phenomenological data the experience of listening to music; however, the lived social world in all its chaos and confusion may not be so amenable to Husserlian analysis. Thus, for Levinas, we do not expect every futural event (Hutchens 2004), and cannot be open to all the indeterminacy of the future. Levinas focuses his account of diachrony through the lack of access one has to the memories of another and the unpredictability of their future. This is added to by what Levinas terms anachrony, the effect the dead, the unborn, and the distant, have on ones temporality.Objective time is always being broken up by the anachrony of lived time, recuperated by memory and expectation. That is, our most basic experience of time comes in the form of social arrangements whose temporality is mostly forbidden to us and, thus, objective time is merely the selfs effort to impose its own time on all time, to reduce the Other to the Same. Time lacks the merely formal nature of the concept of objective time because diachrony is a rupture and continuity of time on many anachronous levels. The anachronous disjunction between synchrony and diachrony, the time of the self and the time of the other person, is the very meaning of discontinuity. The time of lived experience is anachronous, not synchronous, because of the social arrangements that shape our experience. (Hutchens 2004, 74)

Phillips 2003). Thus, could it be that in melancholia the radical alterity of the other (to lapse into Levinasese) is minimized? The other can be more easily rendered the same. The futural events become more predictable, a Levinasian temporality becomes Husserlian, with the possibility of a foreclosure of protention and a static, determinate future. By this account, one could see Husserls aseptic account as a step to pathology, already a withdrawal from the world.

ConclusionThe experience of alteration in time in mood disorders is a powerful and illuminating way into studying depression. Wyllies analysis offers insights that can both help clinically and with empirical research. Further, such insights are important in helping us to appreciate the neuroscience data. The work outlined herein largely supports Wyllies own conclusionsGlicksohn (2001) in particular offers his own phenomenological account of time sense, an account that attempts to deal with issues that preoccupied Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Levinas, namely how our sense of time and temporality is contingent upon our immersion in the lived world and our experiences of being with others. Further, the phenomenological accounts of Husserl can be amenable to contemporary accounts in the language of connectionist models. A contemporary of Henry Maudsleys, and self-described psychologist, offers his own thought experiment when considering time:The heaviest weight.What if some day or night a demon were to steal into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: This life as you now live it and have lived it you will have to live once again and innumerable times again; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unspeakably small or great in your life must return to you, all in the same succession and sequenceeven this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned over again and again, and you with it, speck of dust! Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: You are a god, and never have I

The importance of Levinas account lies in that fact that normal temporal experience is not synchronous. It may be so in certain isolated cases, such as when exercising ones aesthetic sense or perhaps when one is mentally ill. As Wyllie observes, in melancholia ones affective stance to the world is altered and we know that in mood disorder sufferers perceive the affect of others differently (Surguladze, Keedwell, and

BROOME / SUFFERING AND ETERNAL RECURRENCE OF THE SAME

193

heard anything more divine. If this thought gained power over you, as you are it would transform and possibly crush you; the question in each and every thing, Do you want this again and innumerable times again? would lie on your actions as the heaviest weight! Or how well disposed would you have to become to yourself and to life to long for nothing more fervently than for this ultimate eternal confirmation and seal? (Nietzsche 1887/2001, 341, 194 195)

For Nietzsche, if one is able to think this thought through, one will either throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus?, or if one is superman potential would have answered him: You are a god, and never have I heard anything more divine. For the past and the present to be enough would be as much a mark of psychopathology as the opposite. The lack of future (or eternal recurrence) is present in both and what determines how one answers Nietzsches demon may be how one judges ones present and past and thus be heavily colored by ones affect at the time. If melancholic time distortion, Cotards and McTaggarts syndrome are the consequence of severe depression, then Superman syndrome may be the affective corollary in the heights of grandiosity and mania. As Levinas reminds us, protention, or the lack thereof, can go either way. Eternal torment and eternal divinity may be two aspects of the same temporal phenomenon.

ReferencesBechtel, B., A. Abrahamsen, and G. Graham. 1998. The life of cognitive science. In A companion to cognitive science, ed. B. Bechtel and G. Graham, 1104. Blackwell: Oxford. Bernet, R. 2002. Levinas critique of Husserl. In The Cambridge companion to Levinas, ed. S. Critchley and R. Bernsconi, 8299. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bernet, R., I. Kern, and E. Marbeck. 1993. An introduction to Husserlian phenomenology. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. Broome, M. R. 2004. The rationality of psychosis and understanding the deluded. Philosophy, Psychiatry, and Psychology. 11, no. 1:3541. Campbell, J. 2001. Rationality, analysis and the meaning of delusion. Philosophy, Psychiatry, and Psychology 8, no. 2/3:89100. Coull, J. T., F. Vidal, B. Nazarian, and F. Macar. 2004.