Captain Cowper Coles – A disastrous innovator

-

Upload

brian-spear -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of Captain Cowper Coles – A disastrous innovator

World Patent Information 33 (2011) 78–80

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

World Patent Information

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/ locate/worpat in

Captain Cowper Coles – A disastrous innovator

Brian Spear36 Starling Close, Buckhurst Hill, Essex, IG9 5TN, UK

a r t i c l e i n f o

Keywords:InnovatorShipsPatentsCowper ColesObsessive inventorHistorical

0172-2190/$ - see front matter � 2010 Elsevier Ltd. Adoi:10.1016/j.wpi.2010.07.002

E-mail address: [email protected] Note: The Royal Navy (RN) was controlled by the

uniformed RN officers and large numbers of civilians,(Constructors), naval dockyard employees etc. It wasParliament. In the interests of brevity I have referred t

a b s t r a c t

The technical development of the GB Royal Navy in the 19th century is initially described, in particularthe gradual transition from wooden sailing warships to iron warships powered by steam and includingrotatable gun turrets. Against this backcloth, the patenting and other activities of one Captain CowperColes, an obsessive but well connected inventor, are set out. He had 11 GB patents on the turreted andother designs of ships. His ability to influence people of substance, including Queen Victoria’s consortPrince Albert, eventually resulted in Coles receiving a contract to build the HMS Captain. This ship wasso unstable that it sank in a modest storm in 1870, killing 480 of the 500 people on board, including Coles.Effective designs of steam warships with turreted guns were eventually achieved late in the 19th andearly in the 20th century.

� 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Inventors

Inventors require creativity and technical skills but successfulinnovators, those who bring the invention to the market place,usually require an exceptionally self confident and obsessional per-sonality. In the words of one historian:

Absorbed with his own ideas and disposed to magnify their impor-tance and potentialities. He tends to be impatient with those whodo not share his consuming imagination and leaping optimism.He runs to grievances and feels them sharply. The world is againsthim, for it is normally against change and he is against the world,for he is challenging the error or the inadequacy of existing ideas.

Such a mindset can often produce outstanding results- or com-plete disaster. Cowper Phipps Coles (1819–1870) was definitely inthe latter category.

2. Royal Navy (GB)

The 19th Century GB Royal Navy (RN)1 had achieved worldwidesupremacy in the age of sail through outstanding victories in theNapoleonic Wars (1793–1815). Design of wooden sail driven navalwarships had evolved by trial and error over the centuries and theresults were exceptionally stable short range ‘cannon platforms’which were quite difficult to sink except by fire or explosion. GBships were generally no better than their opponents; victory being

ll rights reserved.

Admiralty which comprisedincluding the naval architectsall subject to the control of

o it collectively as the RN.

achieved by the superior professionalism and bravery of their sailors.However, the early 19th century brought new technology to ship-ping including coal powered steam propulsion, iron constructionand eventually long range artillery firing explosive shells. Naturallyafter victory in 1815 the RN rested on its laurels and, money beingshort, was most reluctant to consider technical innovation. Thiswas easily justified as early ship’s engines were so wasteful of coalthat range was limited, while iron constructions corroded andcaused stability problems; moreover they were very vulnerable toartillery fire. Thus, despite GB being the world leader in modernshipbuilding techniques, apart from some experimental vessels,the RN in the late 1850’s was still essentially the sail driven organi-zation of 1815.

3. Naval architecture

Great Britain had successfully negotiated the first 100 years ofthe Industrial Revolution. By 1850 British engineers were theworld’s best but few of them had benefited from formal engineer-ing courses, which barely existed then. On the job training supple-mented by private study had proved sufficient and there waswidespread suspicion of theoretical approaches. Shipbuilding wasno different. A school of naval architecture had been opened inthe RN Dockyard Portsmouth in 1811, but was closed in 1832 bythe reactionary head of the RN Sir James Graham. A new schoolwas opened in 1848 and closed by the same man in 1853. In con-sequence, the Institute of Naval Architects only had 61 qualifiedmembers in 1861 but 390 unqualified associates with an interestin the subject. Given the dearth of trained men and traditional reli-ance on proven wooden sailing ship designs, many experienced

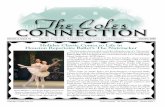

Fig. 1. HMS Captain. Published with permission kindly provided by the NationalMaritime Museum (GB).

B. Spear / World Patent Information 33 (2011) 78–80 79

sailors felt themselves qualified to design ships and often did so,despite the entirely new problems caused by iron construction.

4. Coles – initial activities

Coles had a conventional career, and served as flag lieutenant toan Admiral (an uncle by marriage) in the Crimean War (1854–1856). Here it was found that sail driven warships were ineffectualagainst Russian shore batteries. Coles mounted a heavy gun sur-rounded by thick iron shield on a hastily constructed raft andachieved a minor success which made him a hero in Great Britain.He was ordered to construct a fleet of them, though the war endedbefore this plan could be completed. On the strength of this he con-ceived the idea (correctly as it transpired) that the future of navalgunnery lay in powerful long range guns mounted in rotatable ar-moured turrets and that warships should be designed round this.Not surprisingly, despite having no training in naval architecture,he proposed to design such ships himself!

5. Coles – public agitation

Coles effectively retired from the RN (though still on half pay asa Captain) and dedicated himself to the implementation of the‘‘turreted gun” concept. A feature of the mid Victorian Age wasthe vast increase in the spread and influence of the newspaperindustry which enabled public opinion to be formed and mobilizedto agitate for reform of public bodies in a way that was unthinkablein the past. The coverage of the Crimean War and its official mis-handling had been wonderful for them, especially in The Timesnewspaper, and after this, the authorities were naturally extremelysensitive to their criticism. Coles was well aware of this and, havinga natural flair for publicity, pursued his ideas indefatigably throughthe press, learned bodies, Parliament and his own influential con-nections among high ranking RN officers. His supporters eventuallybecame both numerous and overwhelmingly influential but theirknowledge of naval architecture was at best limited or more usu-ally nonexistent.

6. Coles – patents

Coles filed his first GB patent in 1859 and a regular series there-after on naval topics as detailed in Annex 1. As usual, whether hewas the first inventor is open to dispute as, e.g., John Ericssonhad similar ideas on turrets in the USA, as did Theodore R. Timbeywho was granted two US patents on revolving turrets on July 8,1862. Ericsson’s associates bought Timbey’s patents almost imme-diately. As the GB Patent Office had no search or technical exami-nation at the time the matter was not officially raised. He offeredhis patent rights to the RN for £20,000 (multiply by at least 100to get modern values) but settled for £5000 plus £100 for everyturret installed.

7. Innovation in the 1860’s

By the 1860’s commercial shipping had developed so well thatit was apparent even to the diehards that innovation in the RNcould no longer be delayed. The RN was prepared to have iron builtwarships driven by steam but, as their range was limited by theamount of coal they could carry, wanted a complete set of sailstoo (full rig) for oceangoing ships. The RN employed naval archi-tects (constructors) who were sympathetic to turreted guns butwell aware of the numerous design problems. Given the weightof the turrets and the need to swing them to both sides of the ship,a ship needed a low freeboard which was vulnerable to swampingby the sea. Carrying full sails and their associated stays and rigging

not only interfered with the traverse of the guns but suddensqualls could potentially capsize an unstable iron built ship. Final-ly, iron ships could be built far larger than possible with wood butthey had potential rusting problems. For all these reasons the RNconstructors tended towards caution in new designs, especially gi-ven the limitations of their known naval architecture techniques.

The iron ship Warrior was ordered in 1859 and proved success-ful. Coles was unimpressed and made his own proposals for a mul-ti-turreted ship which were so amateurish that they were easilyrejected by Isaac Watts, the RN’s chief constructor from 1859 to1863. By this time Coles had gained another important backer,Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, who also lobbied for aturret ship. The RN built a satisfactory coast defense warship withturrets, tactfully named it HMS Prince Albert, but managed to limitColes’ contribution to the turrets themselves. Coles hand wasstrengthened by the epic US Civil War naval battle in 1862 be-tween the Monitor and Merrimac where armoured turrets werecrucial and he came up with a greatly improved design whichwas turned down by the new chief constructor Edward Reed(1830–1906) – in office from 1863 to 1870. Coles persuaded theRN to lend him one of its constructors and submitted another de-sign but the RN built their own design HMS Royal Sovereign. Colesnext effort was thwarted as the RN ordered HMS Monarch in 1866,designed by Reed and completed in 1869. Coles responded throughthe press etc. with numerous criticisms and a considerable publicclamour was raised. This was a struggle between Reed and histeam, well qualified men who were making rapid progress in thenaval architecture of iron ships, and a well connected lobbyinggroup. ‘‘Punish the innocent, promote the guilty” has often de-scribed policy outcomes and so it came to pass. Worn down byall this (and despite Reed’s warnings) the RN made the fateful deci-sion that they would purchase a turret ship designed by Coles andbuilt by an RN approved contractor who with Coles, would beresponsible for the outcome.

8. HMS Captain (see Figure 1)

Coles selected Lairds of Birkenhead, an experienced naval ship-builder, and building commenced in January 1867. Coles specifieda large oceangoing iron warship with full turrets, low freeboard,steam engines, a full set of sails and the highest masts in the RN.When completed in 1870 it was noted she was overweight andconsequently floating deeper in the water than intended but Colesand Lairds convinced themselves she was stable and she com-pleted her trials successfully, being a fast mover under both sailand steam.

The Times was delighted in having apparently backed a success-ful design and, when Reed resigned at that time (tired with endlessdisputes on technical matters and his salary), stated [1]:

80 B. Spear / World Patent Information 33 (2011) 78–80

Mr. Reed has often been wrong. In his heated advocacy of broad-sides against turrets and his depreciation of low freeboard forsea-going cruisers, he has manifested too strongly for the publicinterests a personal antagonism to Captain Coles and time has pro-nounced upon these two questions in favour of Captain Coles andadversely to Mr. Reed

However, there was widespread shock when HMS Captain sankwithout warning in a minor storm off Cape Finisterre on 7 Septem-ber 1870. There were only 18 survivors of about 500 aboard andColes was one of the dead. The Times leader of 10 September1870 gave Coles a most fulsome obituary which proved to be thepeak of his reputation.

9. The inquest

This was technically a court martial of the survivors but, inpractice, was a technical inquisition. Among the finding were [1]:

The Captain was capsized... by pressure of sail

The sail carried at the time of her loss... was insufficient to haveendangered a ship endued with the proper amount of stability

The Captain was built in deference to public opinion expressed inParliament, and through other channels, and in opposition to theviews and opinions of the Controller and his department, and thatthe evidence all tends to show that they generally disapproved ofher construction.

Ironically, one of Reed’s assistants, FK Barnes, had managed tosolve the mathematical problem of large angle ship stability by1870 and applied this to HMS Captain, proving her to be unsafeat over 20� of heel. Alas, he only completed his calculations afterthe Captain had set off on her final voyage. Whether his warningswould have been heeded is debatable.

10. Aftermath

Reed went onto a successful career as a naval architect and de-signed ships for a number of other countries, eventually becominga Member of Parliament and being knighted. The RN paid far moreattention to its technical experts, engines improved to the extentthat sails were eventually dispensed with, and turreted warshipsalong the lines Coles originally envisaged were built, culminatingin HMS Dreadnought of 1905 which formed the template for20th century battleship design. Coles was certainly a visionaryinventor but, as with so many, his exceptional drive and self confi-dence blinded him to his limitations. Truly a little knowledge is adangerous thing!

Acknowledgement

I am very grateful for the advice that I received, while research-ing this article, from Melvyn Rees, formerly at the UK-IPO and nowretired.

Appendix A. Annex 1

Eleven GB patents were noted in the name of Cowper Coles:798/1859 Apparatus for defending guns and gunners in ships of

war, gun boats, and land batteries.

1462/1860 Iron-cased ships of war.1027/1862 Masts for ships.1637/1863 An improved method and apparatus for working

guns in vessels and forts, and discharging them under water.411/1864 A new apparatus to be employed in fastening for ar-

mour plates on ships, and in other like fastenings where bolts areused.

1285/1864 Protecting the bottoms and sides of wooden andiron ships and other submerging structures.

1961/1864 Construction of ships of war.3103/1864 Apparatus for working and loading ordnance.3000/1865 Protecting the bottoms and sides of ships and other

structures exposed to the action of sea water.1437/1866 Construction of vessels of war, forts and other

defences.106/1869 Improved means of protecting the bottoms of ships or

other submerged structures, from fouling.US 38151 14 April 1863 Ships masts of iron or steel. Fortunately

the US did not let him design their warships!It is not known if he filed other patents outside GBOne of his sons Sherard O Cowper Coles was also a very prolific

patentee; mostly being interested in electrodeposition.

References

[1] Barnaby KC. Some Ship Disasters and their Causes. London: Hutchinson; 1968.

For more information on Captain Cowper Coles

[2] –The Dictionary of National Biography has detailed entries for Coles, Reed etc.[3] –Preston A. The world’s worst warships, 21–25, 2002, Conway Maritime Press

(and see <http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=EQwO1N-d8tEC&pg=PA21&lpg=PA21&dq=turret+gun+warship+anthony+preston&source=bl&ots=zRWUxixBep&sig=cGWVJxXJ279iPWun-ks2HcGjo80&hl=en&ei=bvJqS4fDMYHw0gT30tXPBA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CA4Q6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=&f=false>)

[4] –‘Son of an old naval officer’. Captain Coles and the Admiralty: with an enquiryinto the origin and quality of ‘‘The Turret System” of Armour-clad war vessels.1866, Longman, Green, and Co (and see <http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=NKgQAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=cowper+phipps+coles&source=bl&ots=aFLocvqi4W&sig=KEwsnWegpOEE0PgFwhP4eB8IvWo&hl=en&ei=YO1qS6Y4hqLSBNarvOAE&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CBsQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=&f=false>)

[5] –<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cowper_Phipps_Coles>.

For more information on HMS Captain

[6] <http://www.hmscaptain.co.uk/Characters/captaincoles.htm>.[7] –<http://www.battleships-cruisers.co.uk/hms_captain_1869.htm>.[8] –<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Captain_(1869)>.

Brian Spear is a Chartered Engineer and Fellow of theInstitution of Electrical Engineers whose career wasspent in the UK Patent Office. This included 22 yearsexamining patents relating to computers, controlsystems and telecommunications. He has also spent10 years on developing computer databases/searching,working in their commercial search arm—the Searchand Advisory Service, and on IPR lecturing to a widerange of organisations. Since retiring he has completedan M.Sc. in the History of Science, Medicine and Tech-nology at Imperial College London.