Cape Cod Magazine

-

Upload

patrickramage -

Category

Documents

-

view

226 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Cape Cod Magazine

last wordOn a Mission to Finish the

Boston Marathon

At the starting line in Hopkinton last year, first-time Bos-ton Marathon runner Patrick Ramage texted his wife, Georgann, to tell her he was turning off his phone and

would see her and the children at the finish line. He then placed his iPhone in his running belt, took a few deep breaths and started the race. Along the idyllic two-lane road, Ramage passed moms and dads still in their pajamas on their front lawn, kids holding cheerful signs, families out grilling.

At around 22 miles, after Heartbreak Hill, a policeman standing on the side of the road shouted, “There’s been an explosion at the finish line.” Ramage’s first thought was 9/11. He quickly reached for his phone, turned it on, and texted, “Are u OK?” to Georgann. Forty-five seconds passed and nothing. His wife re-sponded with a simple text, “We are ok.” He couldn’t stop now. Running was the quickest way he could reach his family on Hereford Street, about a mile from the fin-ish line. But Ramage was stopped at the 24.5 mile mark, where police erected a barricade. Later that day, Ramage was re-united with his family at a friend’s house in Brookline. “We were never so happy to hug, hold hands and share dinner with good friends.”

The Barnstable resident was one of 5,633 runners prevented from completing the race on April 15, 2013. Explosions near the finish line killed three and wounded more than 260 people. The Boston Athletic Association has increased the size of this year’s field to 9,000 for the marathon on April 21.

Ramage, who told people for many months that last year’s marathon would be his first and only, registered again. He’s on a mission to start and finish the 26.2-mile race. Last April’s events turned into something “more meaningful than I ever could have imagined,” Ramage said.

As director of the Global Whale Program for the International Fund for Animal Welfare in Yarmouth Port, Ramage travels the world fighting to protect the planet’s whales. His international travels have allowed him to train in Alaska, San Francisco, To-kyo, and Australia.

He admits the Boston Marathon was never at the top of his buck-

et list. He had run with his dad growing up and always wanted to run at least one marathon (he jokes that “marathon by 40” turned into “marathon by 50”). He knew he couldn’t qualify for the race on his own, so he jumped at the opportunity when IFAW received two charity numbers for last year’s race. Ramage’s colleague, Jason Bell, who directs IFAW’s elephant division in South Africa, also repre-sented IFAW in the race. Each had to raise $5,000 for their organiza-tion. Bell ended up finishing safely ahead of the bombings.

Earlier that beautifully clear marathon day, Ramage joined doz-ens of Cape runners for the ride north aboard a bus sponsored by Hanlon Shoes in Hyannis. Among the passengers was Barnstable

High School principal Patrick Clark, who offered Ramage this advice: “If you make it to where you can see the Citgo sign, the crowd will carry you along.”

But when he got close to the Citgo sign, it was like a ghost town. “In stark contrast to what Patrick Clark had explained to me, it was like a post-Armageddon movie,” says Ramage. “There wasn’t a soul on the sidewalk or street.”

Ramage says he was overwhelmed by the generosity of strangers in nearby town-houses where police stopped the race. Stu-dents started streaming out of buildings offering water, blankets, cellphones, even beer. He took some water from one of the college students, but he spent most of his

time lending his phone to other runners so they could call or text loved ones.The IFAW family has also felt this, says Ramage. IFAW president Azzedine Downes’ nephew Patrick and his wife, Jessica, each lost their left leg below the knee. “I’ve never met Pat and Jess, but I will certainly be thinking about them during this year’s race,” says Ramage.

This past year has forced Ramage to think about how fragile and finite our time is. He says he is a changed man for the better.

“There is more of an urgency and a selflessness about our fam-ily interactions,” he says. “The whole experience, up to the 22-mile mark, was all about me. That changed in an instant. It was a mile-stone in my relationship with my wife and in my role as a father. I have a much more humble and selfless approach to life and a feeling of urgency of time.”

BY Lisa Leigh Connors

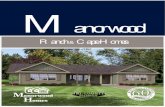

Patrick ramage trains at the YMCa Cape Cod in West Barnstable.

88 cape cod magazine aPriL 2014 www.capecodmagazine.com