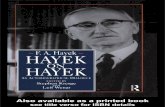

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism Hayek and Socialism

Transcript of Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism Hayek and Socialism

Journal of Economic LiteratureVol. XXXV (December 1997), pp. 1856−1890

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism

Hayek and Socialism

BRUCE CALDWELLUniversity of North Carolina at Greensboro

I have received many helpful comments on this paper from participants at the History ofEconomics Society meetings at the University of British Columbia, at seminars given at theUniversity of Georgia, at the Austrian Colloquium at New York University, at the York Uni-versity-University of Toronto Workshop on the History of Economics, and at the Duke Univer-sity History of Political Economy Workshop. Extensive comments were also received fromPeter Boettke, William Butos, Neil De Marchi, Greg Ransom, and George Selgin. All remain-ing errors are the responsibility of the author.

I. Introduction

MOST ECONOMISTS know thatFriedrich A. Hayek was a life-long

opponent of socialism. But who were hisopponents, what were his arguments,and how did he come to develop them?

In the 1930s Hayek attacked the eco-nomic feasibility of socialism, drawingon arguments from an earlier German-language debate and taking to task anumber of separate proposals for a so-cialist society. This drew a responsefrom Oskar Lange, who advocated mar-ket socialism. The ensuing battle withLange and others led Hayek to de-velop a distinctive “knowledge-based”critique of socialism.

Just before the onset of World War IIHayek began work on a series of articleswhose ultimate result was the publica-tion in 1944 of The Road to Serfdom,his most famous (and in some quarters,notorious) book. The Road to Serfdomcontains Hayek’s political critique of so-cialism, but also the seeds of more posi-tive work. The fruit was his descriptionand defense of an alternative liberal

utopia in such works as The Constitu-tion of Liberty (1960) and Law, Legisla-tion and Liberty (1973−79).

During the war years Hayek also be-came fascinated with questions of meth-odology. This led him, apparently in-congruously, to publish a book on thefoundations of psychology. The SensoryOrder (1952a) is, particularly amongeconomists, Hayek’s least appreciatedbook, yet in a letter to an economistprior to its publication he described itas “the most important thing I have yetdone . . .” (letter to John Nef, Nov. 6,1948). The book provides a theoreticalbasis for the “limitations of knowledge”theme that has been recurrent inHayek’s work. This claim in turn im-plies limits on the ambitions of socialistplanners and other “rationalist con-structivists,” and as such constitutes an-other set of arguments against social-ism. It also implies limits on theambitions of economists, and from anAustrian viewpoint, may help to explainwhy the models of economists have sooften misled them about the prospectsfor socialism.

1856

The paper attempts to answer thequestions provided at the outset, to sur-vey Hayek’s various arguments againstsocialism and to provide some historicalbackground on why he developed themwhen he did.

Recent interpretive literature pro-vides the impetus for the emphasis onhistorical context. Since the events of1989, the Soviet central planning modelhas largely been abandoned by aca-demic advocates of socialism, and a re-newed interest in market socialism hastaken its place. Recent discussions ofmarket socialism by economic theorists,both proponents and opponents, typi-cally draw on insights derived from the“economics of information.” This newperspective views general equilibriumapproaches as inadequate, if not mis-leading, for understanding economicphenomena. Because many of the ear-lier debates on market socialism uti-lized a general equilibrium framework,they are from the perspective of theeconomics of information otiose.

A new interpretation of the debatesover socialism, one that highlights thecontributions of the economics of infor-mation, has begun to emerge (PranabBardhan and John Roemer, eds. 1993,pp. 3−9; Joseph Stiglitz 1994). These in-terpretations are designed to providecontext for recent work, but they typi-cally run into difficulties when they tryto characterize Hayek’s contribution.Though it is evident that Hayek (likethe information theorists) was critical ofusing static general equilibrium modelsfor assessing the merits and limitationsof socialism, it seems clear (and this de-spite his frequent invocation of the con-cept of “knowledge”) that Hayek didnot directly participate in the develop-ment of the economics of information.

How, then, to characterize Hayek’scontribution? From a modern perspec-tive, his work seems “fuzzy” (Louis

Makowski and Joseph Ostroy, in Bard-han and Roemer, eds. 1993, p. 82).Many may well be tempted to concludewith Jànos Kornai (in Bardhan and Roe-mer 1993, p. 63) that “the warnings of aMises or a Hayek about market social-ism” should be viewed as “brilliantguesses” rather than as anything resem-bling “scientific propositions,” or withRobert Heilbroner (1990, p. 1098) that“the successes of the farsighted seemaccounted for more by their prescient‘visions’ than by their superior analy-ses.”

In the final section an alternative,more positive interpretation of Hayek’scontribution is offered. As he becameever more deeply entangled in the de-bates over socialism, Hayek decidedthat a more integrative approach to thestudy of complex social phenomena wasnecessary, that standard economicanalysis taken alone might itself be in-adequate, if not misleading, for under-standing the problems of socialism. Tobe sure, his decision to branch out wasbased in part on his recognition of thelimitations of the static “equilibriumtheory” of his day. But his emphases onthe market as a discovery process, hisconcern with the limits of human cogni-tion, and above all his fascination withquestions of knowledge, what John Gray(1986, p. 134) has aptly called his “epis-temological turn,” led Hayek to insightsthat may well be different in kind fromthose advanced by proponents of theeconomics of information.

If this alternative account is correct,it means at a minimum that those whowould try to read history backwards,who would assess Hayek’s contributionsolely in terms of whether and how heanticipated the later literature on theeconomics of information, will perforcemisunderstand his arguments againstsocialism. So one point of the final sec-tion is to plea for a less ahistorical his-

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism 1857

tory. But it may also be the case thatHayek actually provided an indepen-dent set of claims against market social-ism, one that has been missed by mod-ern information theorists. If so, thenHayek’s apparently “fuzzy” argumentsmay well prove to be of more than“merely historical” interest today.

II. Hayek and the Market Socialists1

Friedrich August von Hayek was bornin Vienna on May 8, 1899. Followingwar service he entered the University ofVienna, where he completed degrees in1921 and 1923. After 14 months ofstudy in the U.S., Hayek returned toAustria in 1925. He spent the rest ofthe decade studying monetary historyand developing a theory of the trade cy-cle. Hayek’s life and the academic mi-lieu of Vienna in the 1920’s is docu-mented in Hayek (1984, Introduction;1992, Prologue; 1994, pp. 47−72) andEarlene Craver (1986).

In the spring of 1931 Hayek was in-vited by Lionel Robbins to deliver a se-ries of lectures on the trade cycle at theLondon School of Economics (LSE).The next year he was appointed to theTooke Chair of Economic Science andStatistics at the LSE, a position hewould hold until he moved to theUnited States in 1950, where he ulti-mately accepted a position on the Com-mittee on Social Thought at the Univer-sity of Chicago. During the early 1930sHayek had exchanges with John May-nard Keynes and Piero Sraffa on mone-tary and trade cycle theory and withFrank Knight on capital theory (Hayek1994, pp. 75−98; 1995). His debateswith the socialists began in 1935 withthe publication of Collectivist EconomicPlanning: Critical Studies on the Possi-bilities of Socialism. The book con-

tained translations of four articles withintroductory and concluding essays pro-vided by Hayek as editor.

A. Prelude—Mises and the German Language Debates

The most important of the translatedcontributions was an article by Ludwigvon Mises that had originally appearedin 1920. The collapse of the Germanand Austro-Hungarian Empires at theend of the First World War opened thedoor for a variety of socialist proposalsfor reorganizing society. Prior to thewar Mises was known as a monetarytheorist and for his unyielding devotionto liberalism. He was as good a personas any to challenge the socialists; in sodoing he initiated the German-languagesocialist calculation debate. DavidSteele (1992, ch. 4) identifies some ofMises’ predecessors, and a number ofwriters (Trygve Hoff, 1949; JudithMerkle 1980, ch. 6; Don Lavoie 1985;Günther Chaloupek 1990) examine thedebates as well as the specifics of vari-ous proposals.

The proposal that most provokedMises was made by the sociologist andphilosopher Otto Neurath. Neurath isremembered today as a member of theVienna Circle of logical positivists andas the inventor of ISOTYPE, the Inter-national System of Typographical Pic-ture Education. Before World War Ihe began to make a reputation as a pro-ponent of a new academic subfield,“war economy.” He also participated,along with Mises, in Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk’s famous economics seminar.Among the other seminar participantswere Joseph Schumpeter, Otto Bauer,who would lead the Austrian SocialistDemocratic party in the 1920s, andRudolf Hilferding, one of the leadingMarxian theoreticians of the 20th cen-tury.

According to Neurath, during peace-1 Parts of this section are adapted from the in-

troduction I wrote as editor for Hayek (1997).

1858 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXV (December 1997)

time, production in market economiesis driven by the search for profits, butthis leads to recurrent periods of over-production and unemployment. In war-time, by contrast, production is nolonger driven by profit-seeking, and thewar effort ensures that productive ca-pacity is always fully utilized. Anothercharacteristic of the war economy is thesuppression of the price system, whichis replaced by extensive planning of ma-terials management from the center.This is all to the good, because for Neu-rath the monetary system, the searchfor profits, and the disorderliness ofcapitalist production all go hand inhand.

Neurath argued that the central plan-ning that emerges within war econo-mies should continue in peacetime. Heproposed that a “natural accountingcenter” be set up to run the economy asif it were one giant enterprise. Mostcontroversially, he insisted that moneywould be unnecessary in the newplanned order: because productionwould be driven by objectively deter-mined needs rather than by the searchfor profits, all calculation regarding theappropriate levels of inputs and outputcould be handled in “natural” physicalterms. In Neurath’s opinion, attemptsto employ monetary calculations withina planned society would render impossi-ble scientific economic management,which had to be conducted in terms of“real” physical quantities.2

Mises (1978, pp. 39−41, 133) plainly

had a strong negative reaction to Neu-rath personally, and as a monetary theo-rist he found his economic claims fan-tastic. (As Chaloupek 1990, pp. 668−70,has shown, most socialists also soon re-jected Neurath’s proposals for a money-less economy.) But he wanted to make amore general case against socialism,one that could be used against otherproposals as well, including those thatretained a role for some form of money.Mises took as a starting premise thatunder most forms of socialism “produc-tion-goods” (factors of production) areowned by the state, and that as suchthere is no market for them. But thisbasic feature of socialism has substan-tial consequences:

because no production-good will ever becomethe object of exchange, it will be impossibleto determine its monetary value. Moneycould never fill in a socialist state the role itfills in a competitive society in determiningthe value of production-goods. Calculation interms of money will here be impossible.(Mises, in Hayek, ed. 1935, p. 92)

Even if money is retained, in the so-cialist state no prices for factors of pro-duction exist. As such, socialist manag-ers have no way to tell when choosingamong a huge array of technologicallyfeasible input combinations which areeconomically feasible. Without someknowledge of relative scarcities, theyare left “groping in the dark.” As Misesput it: “Where there is no free market,there is no pricing mechanism; withouta pricing mechanism, there is no eco-nomic calculation” (in Hayek, ed. 1935,p. 111).

B. Hayek’s Initial Arguments

In his introductory chapter Hayek re-counted the debates that had takenplace in the German language literaturea decade before. In his conclusion heturned to the current scene.

English socialism in the 1930s was a

2 For more on his views, see Neurath (1973, ch.5), Nancy Cartwright et al. (1996, ch. 1), and Ag-nes Miklòs-Illès (1996). The resurgence of interestin Neurath among philosophers is chiefly due tohis pluralistic and anti-foundationalist approach tounified science. Austrian economists focused onhis physicalism, his insistence that, to be meaning-ful, scientific terms must refer to observable phe-nomena. The Austrian economists’ opposition topositivism and scientism in the social sciences de-rives in part from their arguments with such oppo-nents.

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism 1859

mixed bag. The Fabians, whose leadersincluded Sidney and Beatrice Webb andGeorge Bernard Shaw, had been argu-ing for an evolutionary style of socialismsince the late 1880s. The British LabourParty, formed in 1906, officially en-dorsed socialism in its platform. Labourhad prevailed in the general election of1929, but had faltered with Britain’sabandoning of gold in 1931 and spentthe remainder of the decade regroup-ing. Though interest in Guild Socialism,a form of syndicalism, had declined fol-lowing World War I, academic advo-cates like R. H. Tawney and G. D. C.Cole were still active. Barbara Woottonwas the Director of Tutorial Studies atthe University of London, and underher influence a “tutorial version of his-tory,” one which emphasized the dete-rioration of the position of the workingclass under capitalism, was taught inadult education courses throughoutBritain. Maurice Dobb was the leadingspokesman among economists for Marx-ism, and a number of prominent naturalscientists favored communism. Finally,there existed a nascent interest in mar-ket socialism, dubbed “pseudo-competi-tion” by Hayek.3 With no idea which ofhis many opponents might respond,Hayek offered a diversity of criticismsof socialism.

He began with a review of “the Rus-sian experiment,” basing his criticismson the writings of a Russian émigréBoris Brutzkus. This would serve as acounterweight to a more appreciativeassessment of the experiment offeredby the Webbs, whose massive study (itfilled two volumes) was titled SovietCommunism: A New Civilization? when

it was published in 1935. With incred-ibly bad timing, they chose to drop thequestion mark in the 1937 edition.

Next Hayek took up the argument ofHenry D. Dickinson (1933), whoclaimed that Mises was wrong, that ra-tional calculation under socialism was atleast theoretically possible. Because anyeconomy could be formally representedby a Walrasian system of equations,Dickinson claimed that on a theoreticallevel there is no difference betweencapitalism and socialism: In a capitalistsystem the equations are “solved” bythe market, whereas in a socialist sys-tem they could be solved by the plan-ning authorities.

In his rebuttal, Hayek enumeratedmany difficulties associated with “themathematical solution,” or any regimethat relied on formulating and solvinga giant system of equations for therelevant prices and quantities. Hementioned the staggering amount ofinformation that would need to begathered; the immense difficulty of for-mulating the correct system of equa-tions; the hundreds of thousands ofequations that would then need to besolved, not just once but repeatedly;and the inability of such a system toadapt to change.

Should socialist authorities decide to“solve” the system using a trial and er-ror method, an approach also men-tioned by Dickinson, other problemswould arise. The most important ofthese is the inability of any price-chang-ing mechanism to replicate the auto-matic adjustments that occur in a com-petitive free market system in responseto underlying changes in supply and de-mand:

Almost every change of any single pricewould make changes of hundreds of otherprices necessary and most of these otherchanges would by no means be proportionalbut would be affected by the different de-

3 See Elizabeth Durbin (1985) on British social-ism in the interwar years, Gary Werskey (1978) onsocialism among the natural scientists, and the es-says in Philip Bean and David Whynes, eds. (1986)on Wootton. Hayek, ed. (1954) may be read as aresponse to the tutorial version of history.

1860 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXV (December 1997)

grees of elasticity of demand, by the possibili-ties of substitution and other changes in themethod of production. (Hayek, ed. 1935, p.214)

Next Hayek took up the arguments ofthe Marxist Dobb (1933), who notedthat if consumption decisions were alsosubjected to central control, most of theproblems associated with central plan-ning would be alleviated. Hayekpointed out that the abrogation of con-sumer sovereignty implied in such anapproach would presumably be repel-lant to most Britons, and that even un-der such a regime, prices to help guideproduction would still be necessary.

In the last half of his chapter Hayekexplicitly engaged market socialism. Be-cause no concrete proposals were yet onthe table, he had to imagine the formsof market organization that his oppo-nents might propose. One possible ar-rangement is for managers of monopo-lized industries to be directed toproduce so that prices covered marginalcosts, thereby duplicating the results ofcompetitive equilibrium. Hayek’s mostoriginal argument here is that in thereal world (as opposed to the staticworld of perfect competition models) itis typically difficult to know exactlywhat “true” marginal costs are (Hayek,ed. 1935, pp. 226−31). In a market so-cialist regime in which firms within anindustry do compete, a different prob-lem arises: in decisions concerning capi-tal allocation, central planners wouldhave to take over the role played bythousands of entrepreneurs in a marketsystem (Hayek, ed. 1935, pp. 233−37).Hayek clearly considered this to be adisadvantage, but did not specify thenature of the problem. Finally, henoted that the absence of private own-ership in the means of production cre-ates incentive problems for managers,who will put off making difficult deci-sions and who will tend toward risk-

aversion in making investment decisions(Hayek, ed. 1935, pp. 235, 237).

Though Hayek’s two early pieces con-tain fleeting glimpses of his mature po-sition, the modern reader must work tofind them. As Israel Kirzner has con-vincingly argued, the socialist calcula-tion debate served as a

catalyst in the development and articulationof the modern Austrian view of the market asa competitive-entrepreneurial process of dis-covery. . . . it was through the give-and-takeof this debate that the Austrians gradually re-fined their understanding of their own posi-tion. (Kirzner 1988, p. 1; cf. Lavoie 1985)

C. Lange’s Rebuttal

Market socialists are critics of capi-talism, but they also acknowledge thatunder certain conditions perfectly com-petitive markets have desirable effici-ency characteristics. An essential prem-ise of market socialism is the denial thatmarket structures under late capitalismresemble, in any meaningful way, per-fect competition. According to this viewfew competitive industries exist any-more, having been replaced by corpo-rate giants, cartels, and monopolies.Contemporary capitalism thus lacks thebeneficial efficiency characteristics ofcompetition, while retaining all of itsdefects. With careful planning marketsocialism can replicate the benefits oftruly competitive markets, correct forremaining problems regarding effi-ciency, and all the while avoid capital-ism’s pernicious distributional effects.The chief spokesman for this view inthe later 1930s was a Polish émigré toAmerica, Oskar Lange, whose two-partpaper appeared in the Review of Eco-nomic Studies in 1936−37, and was soonreprinted in a book of the same title,On the Economic Theory of Socialism(1938).

Lange’s first argument was directedagainst Mises. Lange agreed with Mises

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism 1861

that prices are necessary for rationalcalculation. Mises’ mistake was to thinkthat prices must be formed in markets.If one instead understands that the cor-rect definition of prices is “terms onwhich alternatives are offered,” and thattheir determination in markets is notessential but rather a peculiarity of aparticular institutional arrangement(capitalism), then Mises’ argument col-lapses. Accounting prices could be sup-plied by the Central Planning Board,and these could be taken by socialistmanagers as parameters in their deci-sion making. Rational calculation undersocialism is not “impossible” after all(Lange 1938, p. 60−62).

Lange’s next step was to demonstratehow a socialist commonwealth could bemade to yield the same results as a truecompetitive market system. In hismodel there exists a free market forboth consumer goods and labor, but(because of public ownership of themeans of production) no market fornon-labor productive resources likecapital. Because labor incomes wouldstill be market-determined, income in-equality would not be eliminated. Butbecause capital ownership is a principalsource of income disparities, its elimi-nation would serve to reduce inequality.Individual incomes would also be sup-plemented by receipt of some share ofthe “social dividend,” the income thathad previously gone to owners of capi-tal.

The sticking point for this variantof market socialism is the absence ofprofit maximizing firms and of a market(and hence of prices that reflect rela-tive scarcities) for non-labor productiveresources. Lange proposed that theCentral Planning Board provide provi-sional “prices” for all goods and factorsof production. Managers of socialistfirms would be instructed to choose, onthe basis of these “given” prices, the

combination of inputs that minimizedtheir costs and the level of outputthat maximized profits. Planners incharge of industries would likewise ex-pand or contract them as necessary,thereby replicating the beneficial ef-fects of free entry and exit under com-petition.

Lange’s proposal begged a key ques-tion: What if the Central PlanningBoard fails to choose prices that accu-rately reflect underlying relative scarci-ties? Here Lange suggested that plan-ners follow a “trial and error”procedure, one similar to that used inactual markets, adjusting prices up ordown in any factor or product marketsin which gluts or shortages existed.Through the trial and error method the“right” set of accounting prices will ulti-mately be found (Lange 1938, pp. 86−89).

Lange responded to Hayek’s concernsabout replacing entrepreneurs with cen-tral planners as follows:

the trial and error procedure would, or atleast could, work much better in a socialisteconomy than it does in a competitive mar-ket. For the Central Planning Board has amuch wider knowledge of what is going on inthe whole economic system than any privateentrepreneur can ever have, and, conse-quently, may be able to reach the right equi-librium prices by a much shorter series ofsuccessive trials than a competitive marketactually does. (Lange 1938, p. 89, emphasis inthe original)

What about the skewing of incentivesunder socialism? Acknowledging theimportance of the problem, Lange of-fered two responses. First, he deniedthat such agency questions are a propertopic for economists to study: “The dis-cussion of this argument belongs to thefield of sociology rather than of eco-nomic theory and must therefore bedispensed with here” (Lange 1935, p.109). Second, he insisted that the realproblem was one of bureaucracy. But

1862 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXV (December 1997)

bureaucratization, he continued, is a ge-neric problem that afflicts both capital-ism and socialism. Because of the ab-sence of competition, the managers of abureaucratic modern capitalistic corpo-ration are as likely to be inefficient asare their counterparts under socialism.The separation of ownership from con-trol exacerbates this: the modern capi-talist corporation is increasingly run bya professional managerial class whosemembers care more about their ownwelfare than about running an efficientfirm. Bureaucracy is a problem of mod-ern life, not one that is unique to social-ism (Lange 1938, pp. 109−10, 120). Tosupport his case Lange cited AdolfBerle and Gardiner Means (1933), theclassic study of the separation of owner-ship from control in the modern corpo-ration and a forerunner of the modernprincipal-agent literature. Lange’s argu-ment underlines again the crucial im-portance for socialists of the claim thatold-style atomistic competition is rareunder late capitalism.

D. Answering Lange—Mises on Appraisement and the Entrepreneur

Mises never directly replied toLange. But it is clear from his laterwritings that he rejected Lange’s claimthat prices are nothing more than“terms on which alternatives are of-fered.” For Mises, prices are social phe-nomena “brought about by the interplayof the valuations of all individuals par-ticipating in the operation of the mar-ket” (Mises 1966, p. 331). They reflectthe plans and appraisements of millionsof acting individuals at a particular mo-ment in time.

Given its origin in the appraisementsof millions of people, the price struc-ture is constantly changing. Even so, itis an essential tool used by entrepre-neurs to make calculations about thehighest-valued use of scarce resources.

Crucially, such calculations are alwaysfuture-oriented.

In drafting their plans the entrepreneurs lookfirst at the prices of the immediate pastwhich are mistakenly called present prices.Of course, the entrepreneurs never makethese prices enter into their calculationswithout paying regard to anticipated changes.The prices of the immediate past are forthem only the starting point of deliberationsleading to forecasts of future prices. . . . Theprices of the past are for the entrepreneur,the shaper of future production, merely amental tool. (Mises 1966, pp. 336−37, empha-sis in the original)

Entrepreneurs must make decisionsabout resource use in a world in whichproduction takes time and in which theconstant evolution of human plans cre-ates a constantly changing structure ofprices. In such an environment errorsclearly are unavoidable. But they do notpersist, because every mistake made byone entrepreneur is simultaneously aprofit opportunity for another: “it is thecompetition of profit-seeking entrepre-neurs that does not tolerate the preser-vation of false prices of the factors ofproduction” (Mises 1966, pp. 337−38,emphasis in the original). Thus theever-changing structure of prices thatexists within a market system, the messygroping that appears so anarchic, endsup being a passably efficient systemfor revealing relative scarcities. Andparadoxically, though the price systemoperates through the self-interested ac-tions of thousands of individuals, its endresult is social cooperation: Paris getsfed.

For Mises, the entrepreneur is theessential actor of the piece, but equallyimportant is that his actions take placewithin a specific institutional frame-work. Absent a market system withwell-defined and enforced propertyrights, the entrepreneur would haveneither the necessary information northe proper incentives to perform his es-

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism 1863

sential function.4 Mises acknowledgedthat Lange’s attempt to introduce pricesand competition into a socialist frame-work showed some recognition of allthis (Mises 1966, p. 706). But withoutthe rest of the requisite institutionalsetting, such efforts must ultimatelyfail.

E. Answering Lange—Hayek on Computation and on Knowledge

Hayek initially responded to Lange ina book review (Hayek [1940] 1948),then elaborated on and extended his ar-gument in a series of articles (Hayek[1945, 1946] 1948; [1968a] 1978).

1. The Computation Problem and“Trial and Error”—Recall that Hayekhad in 1935 already provided argumentsagainst such approaches as “the mathe-matical solution” and, more importantlygiven Lange’s arguments, against thefeasibility of trial and error methods. Inhis review he wondered why Lange hadfailed to address his objections aboutthe latter, and why his opponent hadeven neglected to answer the obviouslyimportant question of how often priceswere to be adjusted under his proposedsystem. Hayek ([1940] 1948, p. 188)added that,

it is difficult to suppress the suspicion thatthis particular proposal has been born out ofan excessive preoccupation with problems ofthe pure theory of stationary equilibrium.

Hayek’s point was a simple one: staticequilibrium theory concentrates onend-points, on a system that has

achieved a state of rest. But the notionof a system moving toward some “final”end-point as determined by “given”data is radically at odds with the situ-ation in the real world, “where constantchange is the rule” (Hayek [1940] 1948,p. 188). Hayek was suggesting thatLange’s use of an equilibrium modelhad misled him into thinking that themovement toward some final equilib-rium set of accounting prices would bea one time adjustment, whereas in real-ity it would be a never-ending process.

Hayek’s arguments about the difficul-ties of coming up with the necessarydata have been challenged by each newgeneration of socialists, as first input-output analysis, then planometrics, thencomputable general equilibrium mod-els, then the advent of supercomputersall promised finally to provide an instru-ment that could replace the market’sprice adjustment mechanism. As a ma-ture Lange (1967, p. 158) provocativelyput it:

Were I to rewrite my essay today my taskwould be much simpler. My answer to Hayekand Robbins would be: so what’s the trouble?Let us put the simultaneous equations on anelectronic computer and we shall obtain thesolution in less than a second.

More recently, Allin Cottrell and W.Paul Cockshott (1993) and Steven Hor-witz (1996) have offered contrasting as-sessments of the feasibility of socialistcomputational proposals.

As a practical matter, though, fewconvincing examples of the successfulreplacement of markets exist. Ironi-cally, the practical effects of the com-puter revolution so far seem to havebeen to undermine the ability of totali-tarian states to restrict access to infor-mation, and to enable entrepreneurs toengage in the sort of “atomistic compe-tition” that socialists of the 1930s hadassumed had died out. It is also note-worthy that within the artificial intelli-

4 Joseph Salerno (1990) recently sparked a livelydebate with the provocative claim that the Mise-sian emphasis on appraisement and entrepreneur-ship differs from, and is more fundamental than,Hayek’s arguments about knowledge. LelandYeager (1994) and Kirzner (1997) contend that thetwo positions are better considered complemen-tary, while Boettke (forthcoming) argues that anydifferences of emphasis that may exist betweenMises and Hayek are due to their responding todifferent audiences.

1864 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXV (December 1997)

gence literature the relationship be-tween markets and computers is becom-ing very nearly the opposite of thatimagined by Lange: rather than regard-ing markets as primitive forms of com-puters, efforts are aimed at makingcomputers replicate the allocational andadaptative characteristics of markets(Lavoie 1990, p. 76).

2. Hayek’s “Knowledge” Arguments—Hayek provided an example of the con-sequences of taking static theories tooseriously in a discussion of Lange’s costminimization rule. Hayek asked: howwill planners come to know what theminimum costs are ([1940] 1948, p.196)? His basic contention was that onlythrough the workings of a rivalrous mar-ket process are ever lower cost methodsof production discovered or created (cf.Hayek, [1946] 1948, pp. 96−97). Stan-dard equilibrium theory misleads by as-suming that an end-state is alreadyreached, so that cost minimizing inputcombinations are already known. Thisobscures the process by which theycome to be known, and may lead to theerroneous belief that one can dispensewith the very process (rivalrous marketcompetition) that generates the knowl-edge. More generally, the static theoryof perfect competition “starts from theassumption of a ‘given’ supply of scarcegoods. But which goods are scarcegoods, or which things are goods, andhow scarce or valuable they are—theseare precisely the things which competi-tion has to discover” (Hayek [1968a]1978, p. 181). In a phrase: Market com-petition constitutes a discovery proce-dure.

Lange had also argued that, becauseentrepreneurs have knowledge aboutonly a limited set of markets and prices,a Central Planning Board (which wouldhave access to more knowledge thanwould individual entrepreneurs) couldmake better capital allocation decisions.

In his 1937 article “Economics andKnowledge” Hayek noted that thoughstandard equilibrium theory assumesthat all agents have access to the same,objectively correct information, in real-ity there is a “division of knowledge.”Actually-existing knowledge is dis-persed; different individuals have ac-cess to different bits of it. Their actionsare based on their varying subjectivebeliefs, beliefs that include assumptionsabout future states of the world andabout other people’s beliefs and ac-tions. The “central question of all socialscience” ([1937] 1948, p. 54) is howsuch dispersed knowledge might be putto use, how society might coordinatethe knowledge that exists in many dif-ferent minds and places. Equilibriumtheory with its emphasis on end-statesassumes that the process of coordin-ation has already taken place. By doingso, it assumes away the most importantquestion.

A number of authors (Caldwell1988a; Kirzner 1988; Meghnad Desai1994) have argued that “Economics andKnowledge” was a seminal piece both inthe development of Hayek’s ideas andfor its implications for the calculationdebate. In his review, Hayek cited thearticle to show that Lange had againbeen misled by “equilibrium theory.”

As I have tried to show on another occasion,it is the main merit of real competition thatthrough it use is made of knowledge dividedamong many persons which, if it were to beused in a centrally directed economy, wouldhave all to enter the single plan. To assumethat all this knowledge would be automat-ically in the possession of the planningauthority seems to me to miss the main point.(Hayek [1940] 1948, p. 134)

Tracing out the implications of the “dis-persion of knowledge” would become an-other major theme in Hayek’s work. Inthe present context, three relatedstrands may be identified. First, freely

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism 1865

adjusting market prices that reflect rela-tive scarcities are profoundly importantwhen errors in perception exist, becausethey help market participants to bringtheir subjectively formed expectations inline with the actual state of the world.Next, much knowledge (particularly ofbusiness conditions) is localized, whatHayek came to call “knowledge of theparticular circumstances of time andplace” ([1945] 1948, p. 80). Finally, cer-tain knowledge is tacit; it is “knowledgehow” rather than “knowledge that”([1968b] 1978, p. 38). Localized andtacit knowledge is difficult (and may beimpossible) to pass on to others, even ifone wanted to.

Modern theorists were quick to pickup on Hayek’s insight that, in a world ofdispersed knowledge, prices convey in-formation. The same cannot be saidabout his writings on localized and tacitknowledge, the importance of which iswell captured in the following exampleprovided by Leland Yeager:

Often an entrepreneur makes business deci-sions partly on his intuition or feel for tech-nology, the attitudes and tastes of consumersand workers, sources of financing, and condi-tions in markets for inputs and for consumergoods and services—all in the future as wellas the present. The entrepreneur receives in-formation for judgments about such mattersby reading specialized and popular publica-tions, watching television and movies, experi-encing various services and products person-ally, chatting with innumerable people, andstrolling through town or the shopping mall.Much of what he thereby observes—orsenses—he could not express in explicitwords or numbers. A socialist system wouldlet much such entrepreneurial knowledge goto waste even if it emerged in the first place.(Yeager 1996, p. 138)

The idea that “the pure theory of sta-tionary equilibrium” is inadequate as atool for understanding the workings of amarket economy, and that it should bereplaced by a view of the market as acompetitive-entrepreneurial process for

the discovery and coordination ofknowledge, has become a central tenetof Austrian thought.5 Hayek’s argu-ments are probably most effective ifone considers centrally controlled so-viet-style economies, where price fixingis extensive and, as a result, the co-ordination of plans is hindered. But theyalso apply to many market socialist re-gimes. In Lange’s proposal, for example,prices were still set by central authori-ties; this is why Hayek insisted thatLange must reveal how often priceswould be adjusted under his “trial anderror” regime. And Hayek’s argumentsabout discovery, error correction, and thecoordination and communication of lo-calized and tacit knowledge apply when-ever entrepreneurs acting within an in-stitutional context of market competitionmake decisions that differ from those oftheir socialist manager counterparts.

Because of its connection to recentdebates on the economics of informa-tion, we will delay until the last sectionour discussion of Hayek’s response toLange on the incentives question. In-stead, we will next examine Hayek’s po-litical arguments against socialism. Hebegan developing the argument in arti-cles written in the late 1930s, but morefamous is the analysis contained in TheRoad to Serfdom ([1944] 1976).

III. The Road to Serfdom

A. Origins of the Book

The Road to Serfdom carries thededication, “To the Socialists of All

5 For more on “market process theory” see Kir-zner (1973, ch. 1; 1997); Ludwig Lachmann(1976); and Esteban Thomsen (1992). Hayek’s wasnot a blanket rejection of general equilibrium the-ory. He thought that even the static Walrasianmodel contained important insights about marketinterdependence, and he spent much of the later1930s in an unsuccessful attempt to develop a dy-namic intertemporal general equilibrium model ofa capital-using monetary economy, as Jack Birner(1994, pp. 2–5) discusses.

1866 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXV (December 1997)

Parties.” This was not just a rhetori-cal swipe; in the 1930s most Britishintellectuals (Hayek’s presumed audi-ence) were sympathetic to socialism(Arthur Marwick 1964). The many dif-ferences that might ordinarily sepa-rate a Liberal-Labour centrist from amember of the Communist Party ofGreat Britain were intentionally down-played once the Popular Front, a unionof leftist groups against fascism,emerged in the middle 1930s. In theirown way even the Conservatives joinedin. In 1938 future Prime Minister (thenthe Conservative MP from Stockton-on-Tees) Harold Macmillan published TheMiddle Way (1938), in which extensivegovernment control of the economy wasextolled. Hayek had little sympathy forsuch views, dubbing them “the muddleof the middle.”

Hayek later reminisced that theoriginal impetus for the book was com-ments made by Lord Beveridge (Hayek1994, p. 102). But he was also fightingagainst the widely accepted view thatNational Socialism and other fascismswere a natural outgrowth of capitalism,and that only by adopting socialismcould the remaining western democra-cies avoid a similar fate. Karl Mann-heim, an academic who had fled Frank-furt in 1933 and who soon gained anappointment in the Department of Soci-ology at the LSE, was one of the moresophisticated proponents of this posi-tion.

Mannheim outlined the causal mech-anisms at work in a lecture beforehis British colleagues first publishedin 1937. His starting premise wasthat monopoly capitalism was the rootcause of widespread and sustained un-employment. In an age of mass democ-racy, orators skilled in the use of thelatest propaganda techniques can ma-nipulate public opinion. Demagoguesemerge who play on the collective

insecurity of the masses, providingscapegoats and offering escape intosymbols of past glories. There is a grad-ual breakdown of societal responsibility,and totalitarian forms of governmentstep in to fill the vacuum. The break-down is aided by capitalists, whoseallegiances are few and fleeting, andwho see new profit opportunities inevery change of regime (Mannheim1940, ch. 3).

Reflecting on the recent experienceof Germany, Mannheim concludedthat the nascent democracies of Mid-dle Europe were lost. He held outsome hope for England, but only if itwould give up liberal democracy andembrace a comprehensive system ofplanning. In the latter half of the booka variety of modern methods ofsocial control are outlined, all of whichcould be used to make the transi-tion from a liberal to a planned soci-ety. What implications did Mann-heim think such planning had for free-dom?

At the highest stage freedom can only existwhen it is secured by planning. It cannot con-sist in restricting the powers of the planner,but in a conception of planning which guar-antees the existence of essential forms offreedom through the plan itself. For every re-striction imposed by limited authoritieswould destroy the unity of the plan, so thatsociety would regress to the former stage ofcompetition and mutual control. (Mannheim1940, p. 378)

Mannheim’s book was received well. Thereviewer in Economica described it as“epoch-making,” adding that “it is de-voutly to be wished that the teaching ofthe book may, though various channels,filter down from the specialist readersand seep into the popular mind, espe-cially into the political mind” (F. Clarke1940, pp. 330−31).

Hayek’s political works of the late1930s and early 1940s may be read as

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism 1867

an attempt to turn arguments likeMannheim’s on their head.6

Rather than the only means of coun-teracting totalitarianism, Hayek arguedthat planning itself constituted a signifi-cant step along the road toward the to-talitarian state.

The main point is very simple. It is that com-prehensive economic planning, which is re-garded as necessary to organize economic ac-tivity on more rational and efficient lines,presupposes a much more complete agree-ment on the relative importance of the differ-ent social ends than actually exists, and thatin consequence, in order to be able to plan,the planning authority must impose uponthe people the detailed code of values thatis lacking. (Hayek [1939] 1997, p. 193; cf.[1944] 1976, p. 57)

******

In the end agreement that planning is neces-sary, together with the inability of the demo-cratic assembly to agree on a particular plan,must strengthen the demand that the govern-ment, or some single individual, should begiven powers to act on their own responsibil-ity. It becomes more and more the acceptedbelief that, if one wants to get things done,the responsible director of affairs must befreed from the fetters of democratic proce-dure (Hayek [1939] 1997, p. 205; cf. [1944]1976, pp. 62−63)

Because of the absence of a sharedcode of values, authoritarian govern-ment tends inevitably to expand beyondthe economic and into the political do-main, even under those forms of social-ism that may have started out as demo-cratic. Mannheim was wrong to thinkthat only under planning would free-dom persist. It was just the opposite:Only if democracy is allied with a freemarket system will freedom of choicebe permitted to exist.

Democratic government has worked success-fully where, and so long as, the functions ofgovernment were, by a widely acceptedcreed, restricted to fields where agreementamong a majority could be achieved by freediscussion; and it is the great merit of theliberal creed that it reduced the range of sub-jects on which agreement was necessary toone on which it was likely to exist in a societyof free men. It is now often said that democ-racy will not tolerate “capitalism.” If “capital-ism” means here a competitive system basedon free disposal over private property, it is farmore important to realize that only withinthis system is democracy possible. When itbecomes dominated by a collectivist creed,democracy will inevitably destroy itself.([1944] 1976, pp. 69−70; cf. [1939] 1997, pp.205−06)

B. Prediction or Warning?

Hayek’s book found a large popularaudience (in America after The Reader’sDigest came out with a condensed ver-sion in April 1945, and among later gen-erations in Eastern Europe whensamizdat copies circulated), but its re-ception within much of the Anglo-American academic community wasnegative. A common criticism focusedon Hayek’s apparent prediction thatplanning must necessarily and inevita-bly lead to authoritarianism; the lastsentence in the quotation above is thesort of passage that gave rise to thecriticism.

This criticism was repeatedly raised,for example, by Wootton in FreedomUnder Planning (1945, e.g., pp. 28, 36−37, 50).7 Wootton’s courteous book wasexplicitly written as a response to The

6 Hayek explicitly identifies Mannheim as an op-ponent in the second chapter of The Road to Serf-dom ([1944] 1976, p. 21); and also mentions himin his ([1941–44] 1952b, pp. 156, 166n) and([1970] 1978, p. 6).

7 Wootton was not unique; such diverse figuresas George Stigler (1988, pp. 140, 147) and PaulSamuelson came away with similar readings. Atone point Hayek sent Samuelson a stronglyworded letter objecting to the latter’s repetition ofthe inevitability thesis in the 11th edition of hisPrinciples text. In a letter dated January 2, 1981,Samuelson graciously apologized and promised totry to represent Hayek’s views more accurately inany future work. See the Samuelson file, Box 48,number 5, in the Hayek Archives, Hoover Institu-tion, Stanford, CA.

1868 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXV (December 1997)

Road to Serfdom. It is also repre-sentative of its genre regarding ques-tions of “human nature.” In the firstnine chapters Wootton assumes that“planners are public-spirited peoplewho seek only to discover the commongood, and to do their best for it” (1945,p. 19). Only in the last chapter is thisassumption dropped; but even there sheinvokes such devices as a better in-formed electorate, more forthright po-litical parties, and oversight by bodiesof concerned citizens to accomplish themanifold goals of planning.

Hayek objected to the criticism, argu-ing that The Road to Serfdom wasmeant to be a warning, not an historicalprediction. He noted that the book’s in-troduction contains such caveats as “nodevelopment is inevitable” (p. 1); “thedanger is not immediate” (p. 2); and,most significantly, “Nor am I arguingthat these developments are inevitable.If they were, there would be no point inwriting this. They can be prevented ifpeople realize in time where their ef-forts may lead” (p. 4).

Certain of Hayek’s other writings,and in particular his methodological cri-tique of “historicism,” may also be men-tioned in his defense. Historicism in-cludes the claim that human historyconsists of “a necessary succession ofdefinite ‘stages’ or ‘phases,’ ‘systems’ or‘styles,’ following each other in histori-cal development.” But Hayek rejectedthis historicist endeavor “to find lawswhere in the nature of the case theycannot be found . . .” ([1941−44] 1952b,p. 128). Given his clear statements thatthere exist no immutable laws dictatinginevitable historical trends, he was sur-prised to find others claiming that hehad sought to demonstrate the exist-ence of such a trend.

One can see why the “prediction orwarning” issue is an important one. Ifone takes Hayek’s words as predictions

of inevitable trends, the events foretoldobviously did not come to pass in En-gland, the country Hayek had in mindwhen writing the book. If one takesthem as warnings, however, his later re-marks about the negative “psychologicaleffects” of postwar Labour rule in Brit-ain become more comprehensible, per-haps even apposite (Hayek [1944] 1976,pp. x−xvi).

A final point may help put the dis-pute into perspective: Neither Mann-heim’s nor Hayek’s books were uniquein their times. The western world wasturned upside down, and all manner ofintellectuals, from journalists like Wal-ter Lippmann (1937), to economists likeSchumpeter ([1942] 1950) and Karl Po-lanyi (1944), to philosophers like JamesBurnham (1941), to historians like Ed-ward H. Carr (1945), felt compelled toruminate on its past development, pre-sent dilemmas, and future prospects.

None of the other authors, though,quite shared Hayek’s fate. He had ahard time finding a publisher for thebook, when it finally appeared some ofhis critics’ reactions bordered on the li-belous (e.g., Herman Finer 1945), andHayek later was to claim that the book“went so far as to completely discreditme professionally” (1994, p. 103). Thisis one reason why the book should beread today. Readers who know it onlyby its reputation will be surprised tofind that it contains a number of recom-mendations for state intervention in theeconomy, as is evident in the following(admittedly qualified) passages:

There is no reason why in a society whichhas reached the general level of wealth whichours has attained the first kind of security [hehad earlier mentioned “security against se-vere physical privation, the certainty of agiven minimum of sustenance for all”] shouldnot be guaranteed to all without endangeringgeneral freedom. There are difficult ques-tions about the precise standard which shouldthus be assured; there is particularly the im-

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism 1869

portant question whether those who thus relyon the community should indefinitely enjoyall the same liberties as the rest. An incau-tious handling of these problems might wellcause serious and perhaps dangerous politicalproblems; but there can be no doubt thatsome minimum of food, shelter, and clothing,sufficient to preserve health and the capacityfor work, can be assured to everybody.

******

Nor is there any reason why the stateshould not assist the individuals in providingfor those common hazards of life againstwhich, because of their uncertainty, few indi-viduals can make adequate provision. Where,as in the case of sickness and accident, nei-ther the desire to avoid such calamities northe efforts to overcome their consequencesare as a rule weakened by the provision ofassistance—where, in short, we deal withgenuinely insurable risks—the case for thestate’s helping to organize a comprehensivesystem of social insurance is very strong.(Hayek [1944] 1976, pp. 120−21)

Hayek’s remarks are qualified, but itseems clear that, at least in 1944, he waswilling to countenance some level of“safety net” policy. In a new preface forthe book prepared in 1976, however,Hayek wrote that “I had not wholly freedmyself from all the current intervention-ist superstitions, and in consequence stillmade various concessions which I nowthink unwarranted” ([1944] 1976, p. xxi).

C. Liberty and Knowledge—Hayek’s Alternative Liberal Utopia

Hayek’s initial arguments promptedone socialist critic (Dickinson 1940) tochallenge him to describe his ideal lib-eral society in more detail. After read-ing The Road to Serfdom, Keynes alsochallenged Hayek to state clearly thecriteria he would use to distinguish ac-ceptable from pernicious governmentintervention (Jeremy Shearmur 1997).Though these tasks were begun in his1944 book, Hayek’s most refined re-sponse to his critics may be found in

The Constitution of Liberty (1960).8 And indeed, Hayek’s prolonged effortto explore the origins, nature, and sus-tainability of a liberal market order isprobably the most important legacy ofThe Road to Serfdom.

Hayek (1960, p. 11) began by defin-ing “liberty” as a condition “in whichcoercion of some by others is reducedas much as possible in society.” Thisproduces a dilemma, because the bestway to avoid coercion is to set up a co-ercive power that is strong enough toprevent it. Free society has met theproblem by defining a private sphere ofindividual activity, granting the state amonopoly on coercion, then constitu-tionally limiting the power of the stateto those instances where it is requiredto prevent coercion. The state’s coer-cive actions are constrained by the ruleof law: the laws it makes in protectionof the private sphere must be prospec-tive, known, certain, and equally en-forced (pp. 205−10). Hayek contraststhese with laws that seek specific out-comes within the private sphere, suchas certain redistributive patterns (p.232). What especially rankled him wasthe attempt to turn what Hayek viewedas legitimate “safety net” insuranceschemes into explicit instruments of re-distribution aimed at securing “socialjustice” (e.g., p. 289). In his discussionsof old age and health insurance policy,some of his dark warnings about inter-generational political strife make fortimely, if uncomfortable, reading today(e.g., pp. 295−98).

In his political writings Hayek fre-quently stated that he was no fan oflaissez-faire. By this he meant that a

8 Hayek’s other major contribution was the tril-ogy Law, Legislation and Liberty (1973–79),which contained his diagnosis of why liberal de-mocracies were being taken over by special inter-ests, and a proposed legislative reform aimed atstrengthening liberal constitutionalism.

1870 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXV (December 1997)

market system must be embedded in aset of other institutions—a democraticpolity, with strong constitutional pro-tection of a private sphere of individualactivity, with enforced and exchange-able property rights—if it is to work.The problems of the Eastern Europeantransition have made these ideas seemalmost obvious, and they are ancientideas. But Hayek was stressing them be-fore they (re)gained popularity.

Hayek also linked liberty to his recur-ring theme, the problem of how tomake use of dispersed knowledge. Associety progresses the division of knowl-edge increases, as does our dependenceon the knowledge possessed by others:“When we reflect how much knowledgepossessed by other people is an essen-tial condition for the successful pursuitof our individual aims, the magnitude ofour ignorance of the circumstances onwhich the results of our action dependappears simply staggering” (p. 24). Themost successful societies are those inwhich each individual is able to put hisown local knowledge to its best uses.From this perspective, The Constitutionof Liberty describes the complex of in-stitutions and beliefs that promote thediscovery, transmission, and use ofknowledge so that individuals mighthave the best chance to have success inpursuing their own goals. Chief amongthe enabling conditions is liberty itself:

The rationale of securing to each individual aknown range within which he can decide onhis actions is to enable him to make the full-est use of his knowledge, especially of hisconcrete and often unique knowledge of theparticular circumstances of time and place.The law tells him what facts he may count onand thereby extends the range within whichhe can predict the consequences of his ac-tions. (pp. 156−57)

Hayek’s political philosophy is notuncontroversial. Critics have pointedout that he mixes a number of different

ethical and political philosophies to-gether, positions that may not cohereand all of which have been indepen-dently criticized; that in particular it isdifficult to square his Kantian ethicalideas about universalizability with hisHumean epistemological pessimism;and that the characteristics he requiresthat laws possess are not adequate toguarantee liberty (Arthur Diamond1980; Chandran Kukathas 1989; Gray1986, ch. 6). If one is judging his workagainst the standard of whether he pro-vided a finished political philosophy,Hayek did not succeed though Shear-mur (1996) contains a diagnosis of whatwould need to be done to build a coher-ent liberal political philosophy startingfrom Hayek’s foundations, and an ad-mittedly preliminary attempt to beginthat enterprise. It nonetheless remainsan impressive attempt to construct anintegrated system of social philosophy,one that blends insights from such di-verse fields as economics, political phi-losophy, ethics, jurisprudence, and in-tellectual history. And it is hard to denyHayek’s foundational contention that aliberal order allows individual knowl-edge to be better used than does social-ism.

IV. Hayek and Spontaneous Orders

A. The Critique of Rationalist Constructivism

Hayek’s final set of arguments againstsocialist planning begin from the prem-ise that the market system and certainother social institutions are examples ofspontaneously organized complex phe-nomena, spontaneous orders which gen-erate unintended beneficial conse-quences for those lucky enough to liveunder them. Now especially in mid-cen-tury, most of Hayek’s readers wouldhave thought it quaint to consider themarket system as a paradigmatic exam-

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism 1871

ple of a self-organizing system. Forthem it was more like a machine thathad broken down, something that re-quired radical repair, if not outright re-placement. Hayek labeled this opposingviewpoint “rationalist constructivism,”located its origins in the French ration-alist variant of Enlightenment thought,and used it as a kind of foil in manylater writings. Thus, according toHayek, rationalist constructivists be-lieved:

that human institutions will serve human pur-poses only if they have been deliberately de-signed for these purposes, often also that thefact that an institution exists is evidence of itshaving been created for a purpose, and al-ways that we should so redesign society andits institutions that all our actions will bewholly guided by known purposes. To mostpeople these propositions seem almost self-evident and to constitute an attitude aloneworthy of a thinking being. (1973, pp. 8−9;also see his [1964a] 1967; [1970] 1978)

Hayek’s earliest critique was aimed at“the engineering mentality” (1952b, ch.10) of the “men of science” ([1941] 1997;cf. Editor’s Introduction), but his targetwas later broadened to include propo-nents of rationalism, empiricism, positiv-ism and utilitarianism (1988, pp. 60−62).Hayek’s apparently creative historiogra-phy has been challenged by both Dia-mond (1980) and Gray (1988).

Following Carl Menger ([1883]1985,Book 3), Hayek argued that spontane-ous social orders are products of humanaction but not intentionally designed.Such institutions evolved gradually, andonly after they emerged were their ad-vantages recognized, first by certain ofthe Scholastics, then by various mem-bers of the Scottish Enlightenment, andthen again by Menger. Hayek’s fasci-nation with such orders began back inthe 1930s ([1933] 1991, pp. 17−34;Caldwell, 1988b, discusses the impor-tance of the piece), and indeed is evi-

dent in the question he broached in“Economics and Knowledge” about howhuman action gets coordinated even inthe absence of a central controllingauthority. In his early writings the co-ordinating role of freely adjusting mar-ket prices was highlighted. But soonHayek began including all sorts of prac-tices, norms, rules and other forms ofinstitutions as aiding social coordi-nation. Thus he would argue that suchinstitutions as language, the law, andmoney emerged because they contrib-uted to the ability of individuals to pur-sue their own goals; that our moralswent through a similar sort of culturalevolution; and that (as we shall soonsee) even the ordering of neural net-works within the human brain developsanalogously.

Hayek employed his account of cul-tural and institutional evolution to criti-cize the view that society can recon-struct institutions or moral codes to bemore rational. As always, knowledgequestions played a prominent role inthe argument. Hayek believed thatspontaneously emerging practices, normsand institutions not only allow humansto use knowledge better, they also per-mit knowledge gained in the past to bepreserved, because they are artifacts re-flecting the experimentation of manypeople over long periods of time:

Far from assuming that those who createdthe institutions were wiser than we are, theevolutionary view is based on the insight thatthe result of the experimentation of manygenerations may embody more experiencethan any one man possesses. (1960, p. 62)

As a result, attempts to radically alter orreconstruct these institutions are fraughtwith dangers; we simply do not haveenough knowledge about what they doand how they do it. Given our ignorance,only “the hubris of reason” would leadone to believe that we can rebuild soci-ety from the ground up (1973, p. 33).

1872 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXV (December 1997)

“Reason properly used” understands thelimits of what reason can do; like DavidHume before him, Hayek sought to“whittle down the claims of reason bythe use of rational analysis” (1960, p.69). The implication for economic analy-sis was for Hayek straightforward: “whatwe can know in the field of economics isso much less than people aspire to”(1983, p. 258).

Hayek’s evolutionary arguments havebeen extensively criticized (particularlyhis reliance in later work on the idea of“group selection”), perhaps most effec-tively by those like Viktor Vanberg(1994, chs. 5−7 & 12) who believe thatthe design of constitutions is an essen-tial element in the improvement of lib-eral orders. And Hayek, after all, wasnot averse to making proposals aboutconstitutional design himself (1979, ch.17), in apparent violation of his ownstrictures concerning constructivism.But he was also concerned with howspecific instances of liberal market or-ders ever came to be created in the firstplace, particularly because they sit souneasily with, as he put it (1988, ch. 1),both our “instinct and reason.” This is aquestion that his critics have thus farleft unanswered.

In any event, one particular exemplarof Hayek’s treatment of spontaneous or-ders, his book on the foundations oftheoretical psychology, The Sensory Or-der (1952a), has not been much studiedby economists (exceptions include Wil-liam Butos and Roger Koppl 1993;Horowitz 1994; and Steve Fleetwood1995). The book does not deal even pe-ripherally with socialism. But properlyunderstood it provides a key for com-prehending the nature and extent ofHayek’s divergence from mainstreameconomics in the postwar period, and somay help to explain why modern infor-mation theorists writing about marketsocialism have had such a hard time un-

derstanding him. As such, a short di-gression follows.

B. A Digression—The Sensory Order

During the war Hayek began a majorproject, one with both historical andmethodological dimensions, on “theabuse of reason.” As he later explained(1952b, pp. 10−11), the larger projectwas never completed, but he did finishan extended piece on methodology enti-tled “Scientism and the Study of Soci-ety” (reprinted in Hayek, 1952b). Theessay contains a critique of the idea thatthe methods that had been so successfulin the natural sciences should also beapplied in the social sciences; “scien-tism” refers to what Hayek called the“slavish imitation” (1952b, p. 24) by so-cial scientists of (what often turned outto be a caricature of) such methods. Healso offered a positive methodologicalalternative to scientism. His startingpoint was to describe what he took tobe the central subject matter of the so-cial sciences: the acting individual.Hayek outlined some fundamentalpremises about the mind of such an in-dividual, and about the relationship be-tween beliefs and action. Among thepremises were: the structure of the hu-man mind is everywhere the same; ouractions are based on our “opinions”(presumably these include both percep-tions and beliefs); these opinions aresubjectively held (and as such, some arewrong); finally, perceptions and beliefsdiffer among individuals.

Turning from a description of thesubject matter of the social sciences toa discussion of how best to study it (thatis, from ontology to methodology),Hayek proposed a “compositive” meth-odology in which the social scientist’stask is to show how the actions of manysuch individuals come to constitutebroader, more complex social phenom-ena. In his examination of the issues,

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism 1873

Hayek reached a crucial conclusion:when studying complex phenomena,typically one cannot predict individualactions. Pattern predictions, or explana-tions of the principle underlying thecomposition of social phenomena, areusually the best one can do (Hayek1952b, chs. 3 & 4; cf. Caldwell 1989).

Hayek’s next step was to try to pro-vide a firmer basis for his statementsabout the nature of mind. In the sum-mer of 1945 he dug out a manuscript onpsychology that he had written duringhis student days in Vienna nearly aquarter of a century earlier. The essayformed the basis for his next major con-tribution, The Sensory Order (1952a).

It appears that Hayek viewed TheSensory Order as providing the physi-ological underpinning for the varioustheses he had advanced concerning therelationship between mind, knowledge,and human action in the “Scientism” es-say.9 Hayek began by distinguishing be-tween the physical order existing in theexternal world and our phenomenal ex-perience of it. Our sensations, our per-ception of the qualities of objects, ourwhole mental image of the world, startfrom stimuli received through our cen-tral nervous system. This central nerv-ous system constitutes the common“structure of the mind” shared by all in-dividuals that had been posited in “Sci-entism.”

The system provides a relational or-dering of stimuli: the sensory order.The qualitative differences in percep-tions and sensations that we experiencedepend on the specific pattern of neu-ron firings that a given stimulus pro-duces within various neural networks.The experiences and beliefs of individu-

als will differ according to the patternof neural firings that each develops.Thus though the structures of ourminds are the same, there is a physi-ological basis for the notion of a disper-sion of perceptions and experiencesand, ultimately, of knowledge. The sen-sory system that results as the individ-ual interacts with and receives feedbackfrom the environment is both self-orga-nized and adaptive, one that is con-stantly adjusting (strengthening certainpathways and connections, while dimin-ishing the strength of others) as newstimuli come in. The adaptations repre-sent “learning” by the individual.

C. The Significance of The Sensory Order

The Sensory Order clearly heralds thefull emergence of complex “spontane-ous orders” as a theme in Hayek’s work.But for our purposes, its import lies inviewing it as Hayek’s decisive step awaynot just from the study of economics,but from standard economic reasoning,as well.

To see this note that, first, The Sen-sory Order provides a naturalistic onto-logical grounding for a number of meth-odological prescriptions. Both therecourse to ontology and the specificmethodological prescriptions Hayek de-rived were diametrically opposed to thephilosophical world view not just ofmost mainstream economists of his day,but of psychologists as well.

In mid-century, positivism and instru-mentalism were the philosophicaldoctrines that most influenced themethodological self-consciousness ofpsychologists and economists. Positiv-ists eschewed talk of ontology or meta-physics, and measured the veracity oftheories not by their ontologicalgrounding but by their ability to allowscientists to control or predict phenom-ena. This was the reasoning that al-

9 Hayek links the two essays in a retrospectivepiece (1982a, p. 289), and in his letter to John Nef(cited earlier). Further, the “Scientism” essay isthe only work by Hayek cited in The Sensory Or-der.

1874 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXV (December 1997)

lowed behaviorist psychologists to denyscientific status to any and all attemptsto “get beneath” observable behavior todiscover its origins in human conscious-ness. Likewise, both Paul Samuelson’srecourse to “revealed preference” andMilton Friedman’s “as if” methodology(that is, the claim that the realism ofa theory’s assumptions is unimportantcompared to its ability to predict) sharethe positivist emphasis on observablephenomena and prediction. (The meth-odological positions of both Samuelsonand Friedman are examined in detail inCaldwell [1982] 1994.)

This aversion to ontology was exactlythe sort of view that Hayek attacked inboth the “Scientism” essay and in TheSensory Order. Furthermore, by provid-ing a grounding for his methodologicalclaims in physiological psychology,Hayek believed that he was the one whowas truly being “scientific.” Hayek’spsychological work is now recognized asan early challenge to behaviorism (e.g.,Gerald Edelman 1987, ch. 1; DonaldHebb 1949 was another early dis-senter), and his ontological boldness ex-plains his attractiveness to scientific re-alists of today like Tony Lawson (1994)and Fleetwood (1995).

The specific methodological conclu-sions that Hayek drew also contradictedthe positivistic dogma of the time. Asnoted above, when considering complexphenomena, Hayek claimed that typi-cally the best that we can do is to ex-plain the principles by which they work.To the extent that prediction is possibleat all, only broad “pattern predictions”may emerge (1952b, ch. 8; cf. [1955]1967, [1964b] 1967). Such pessimisticclaims about the ability of economists topredict may sound a bit less controver-sial today. But when he was writing andfor a number of decades to come itwould separate him from nearly allmainstream economists, even those, like

his colleagues at the University of Chi-cago, whose views on policy were oftenvery similar to his.

Finally, The Sensory Order markedHayek’s further movement away fromthe constructs used by economists tounderstand the market order. For main-stream economists, the concepts of“equilibrium” and “rationality” are vir-tually coextensive with economic analy-sis. By the middle of the century Hayekbelieved that neither one shed muchlight on the most important questions.

Recall that in “Economics andKnowledge” Hayek had asked: Howdoes human action get coordinatedwhen knowledge is limited and dis-persed? In light of this question, he feltthat the “equilibrium theory” of his daywas of little use: in equilibrium, full co-ordination has already occurred. Stan-dard theory also assumed the presenceof rational agents who all share thesame, objectively correct information.The individual described by Hayek inThe Sensory Order had little in com-mon with this “rational (and fully in-formed) economic man” construct.

Hayek never explicitly tried tochange economics, he never argued thathis own description should replace “ra-tional economic man” within economicmodels. And certainly a central ques-tion is what difference Hayek’s variousdepartures all might make. One way tosee is briefly to examine the latest in-stallment of the market socialism de-bates.

V. Market Socialism and the Economicsof Information

A. A New Chapter in the History of the Debate over Socialism

There is renewed interest in marketsocialism, and emerging with it hasbeen a new stylized history of the de-bates, one that highlights the contribu-

Caldwell: Hayek and Socialism 1875

tions of the economics of information(Bardhan and Roemer, eds. 1993, pp.3−9; Stiglitz 1994).

The first part of this history incorpo-rates the conventional story that hadbeen told about the socialist calculationdebate through about the 1970s, withAbram Bergson (1948) being the classicearly statement (see Lavoie 1985, how-ever, for a modern revisionist reply). Inthat account, the debate was opened byvon Mises, who declared the “impossi-bility” of rational calculation under so-cialism. The “mathematical solution” ofDickinson, which utilized the Paretianor Walrasian general equilibrium modelto show the formal similarities betweena socialist and capitalist regime, under-mined Mises’ claim of impossibility.Hayek’s contribution via his “complexityargument” was to question the practicalfeasibility of solving a general equil-brium system. Lange’s proposed “trialand error method” undercut Hayek’sclaim, and the actual feasibility of so-cialism then became viewed as an em-pirical matter. Later the emergence ofsupercomputers and of computable gen-eral equilibrium models suggested thatthe complexity problem might well besoluable, so that the actual estab-lishment of a viable socialist state mightonly be a matter of time.

But this was not to be. The poor per-formance of communist regimes sug-gested that the chief problem was notone of computation, but of “incentivecompatiblity.” In the new account theWalrasian general equilibrium model(or its more recent counterpart, the Ar-row-Debreu model) became the villainof the piece, and particularly its impli-cation that a purely competitive systemwill yield efficient market outcomes, al-beit once a stringent set of marginalconditions is met. If information isasymmetric, however, deviations from aPareto-efficient outcome can occur.

While economists in earlier periods mayoccasionally have hit upon specific in-stances of information problems (e.g.,Berle and Means 1933), the Arrow-De-breu framework posed an obstacle, di-recting attention away from questionsof information.

In contrast, the economics of infor-mation provides a systematic means ofidentifying and classifying the wide ar-ray of problems that informationalasymmetries can produce. For example,within a planned economy variousmonitoring problems may arise: produc-tion managers might decide to feathertheir own nests, to seek patronage, topractice favoritism, or in other ways todeviate from the plan; product quality,being multidimensional, is difficult tomonitor; and so on. Nor is it an easymatter for the government to designand enforce a system of constraints toprevent managers from behaving oppor-tunistically. A government that is in anyway responsive to an electorate will findit difficult to commit itself credibly tostringent actions, such as raising pricesfor consumer goods, shutting down pro-duction lines when product demand de-clines, firing well-liked but incompetent(or worse, unlucky) managers, or in-forming redundant workers that theymust be retrained or transferred. Butplant managers confronted with such“soft budget constraints” (so dubbed byKornai 1986) are less likely to take theirproduction goals seriously. Investmentdecisions also pose problems, because itis difficult to avoid either too much ortoo little risk-taking behavior, and with-out competing projects, it becomesproblematical even to assess whether aninvestment once undertaken is in facteconomic (Roemer 1993, pp. 91−92).

As these brief examples suggest, theeconomics of information provides apowerful set of tools for identifying andanalyzing the problems of a socialist

1876 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXV (December 1997)

economy. According to the new history,current models greatly improve onthose of the past because they contain asophisticated understanding of agencyproblems. Indeed, if one accepts thisaccount, the evolution of the variouspositions in the socialist calculation de-bate becomes a paradigmatic exampleof how theoretical progress can occur,and has occurred, in economics.

Perhaps inevitably, historical ac-counts that emphasize progress tend to-ward Whiggism: the work of economistsin the past is but a prelude to develop-ments in the present. Stiglitz, for exam-ple, invokes the debates of the 1930s,but mostly as window dressing. Hisbook Whither Socialism? (1994) is bestread as a celebration of the economicsof information, one that uses the ques-tion of the viability of socialism as itschief application.10

Other accounts treat the argumentsof the 1930s more carefully (e.g., Bard-han and Roemer 1993, pp. 3−9). Be-cause of their reliance on a full informa-tion general equilibrium framework,Lange and other market socialists farepoorly because they (inevitably) ignoredthe question of incentives. Hayek makesfor a harder interpretive case. To besure, he did understand that the pricesystem is a mechanism for conveying in-formation, and modern theorists arequick to acknowledge this. Thus in hiscollection The Informational Role ofPrices (1989), Sanford Grossman quotesin three different articles the same pas-

sage from Hayek’s “The Use of Knowl-edge in Society” (1945) about the pricesystem as a communication mechanism.In a popular textbook, Hayek is cred-ited with having provided the initial in-sight later formalized by Leonid Hur-wicz about the low informationalrequirements of a decentralized pricesystem (Paul Milgrom and John Roberts1992, p. 85).

But this only raises a new set of ques-tions. Given the limited nature of histools, how was it that Hayek stumbledonto the insights that he did? And giventhat Hayek’s critique of Lange focusedon how changing relative prices conveyknowledge, why did he make so littleheadway toward developing an econom-ics of information? This last question ispointedly raised by Makowski and Os-troy who, noting that the field of“mechanism design” differentiates be-tween (i) the information/communica-tion requirements of mechanisms, and(ii) the incentive properties of mecha-nisms, are led to the following assess-ment of Hayek’s contribution:

Failing to emphasize incentives as he did andconcentrating on the problem of communica-tion, Hayek should have arrived at a conclu-sion much closer to market socialism than hedid. Of course it could be noted that whereasthe division between (i) and (ii) may be ana-lytically useful, it is clearly artificial—anymechanism is a composite of (i) and (ii). If, asit seems to us, Hayek did not recognize theneed to separate the two functions (equiva-lently, to separate communication of informa-tion from elicitation of information), his cri-tique of market socialism is “fuzzy.” (inBardhan and Roemer, eds. 1993, p. 82)