Cacium and Vitamin D in Nefrotic Syndr

-

Upload

ranti-adriani -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

0

Transcript of Cacium and Vitamin D in Nefrotic Syndr

-

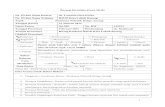

7/25/2019 Cacium and Vitamin D in Nefrotic Syndr

1/7

Int J Pediatr (Supplement.1), Vol.3, N.2-1, Serial No.15, March 2015 103

Review Article (Pages: 103-109)

http:// ijp.mums.ac.ir

Calcium and Vitamin D Metabolism in Pediatric Nephrotic

Syndrome; An Update on the Existing LiteratureMohammad Esmaeeili 1, Anoush Azarfar 1, *Samane Hoseinalizadeh 1 1

1Department of Pediatric, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

Abstract

Minimal Change Disease (MCD) is the leading cause of childhood Nephrotic Syndrome (NS).Therefore in pediatrics nephrotic syndrome, most children beyond the first year of life will be treatedwith corticosteroids without an initial biopsy. Children with NS often display a number of calciumhomeostasis disturbances causing abnormal bone histology, including hypocalcemia, reduced serumvitamin D metabolites, impaired intestinal absorption of calcium, and elevated levels ofimmunoreactive Parathyroid Hormone (iPTH). These are mainly attributed to the loss of a variety of

plasma proteins and minerals in the urine as well as steroid therapy. Early diagnosis and managementof these abnormalities, could prevent the growth retardation and renal osteodystrophy that affectschildren with nephrotic syndrome. Here we reviewed the literature for changes of calcium and vitaminD metabolism in nephrotic syndrome and its consequences on bones, also the effect of corticosteroidand possible preventive strategies that could be done to avoid long term outcomes in children.Although the exact biochemical basis for changes in levels of calcium and vitamin D metabolites in

patients with NS remains speculative; because of the potential adverse effects of these changes amonggrowing children, widespread screening for vitamin D deficiency or routine vitamin Dsupplementation should be considered.

Key Words : Calcium, Nephrotic Syndrome, Review, Vitamin D.

* Corr esponding A uthor :

Samane Hoseinalizadeh, MD, Resident of Pediatric, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of MedicalSciences, Mashhad, Iran.

Email: [email protected] date: Jan 21, 2015 ; Accepted date: Feb 22, 2015

mailto:[email protected]:[email protected] -

7/25/2019 Cacium and Vitamin D in Nefrotic Syndr

2/7

Calcium and Vitamin D Metabolism in Pediatric Nephrotic Syndrome

Int J Pediatr (Supplement.1), Vol.3, N.2-1, Serial No.15, March 2015 104

Introduction

In children up to the age of 16 years,the most frequent glomerular disease is

idiopathic nephrotic syndrome includingminimal change disease, Focal SegmentalGlomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and diffusemesangial proliferation, with MCD beingthe most common form. So the termminimal change disease has becomesynonymous with steroid-sensitiveidiopathic nephrotic syndrome; thereforein pediatrics nephrotic syndrome,considering MCD as the most probablediagnosis, most children beyond the first

year of life will be treated withcorticosteroids without an initial biopsy (1-3).Children with NS often display a number

of calcium homeostasis disturbancescausing abnormal bone histology,including hypocalcemia, reduced serumvitamin D metabolites, impaired intestinalabsorption of calcium, and elevated levelsof immunoreactive Parathyroid Hormone(PTH). Serum phosphorus concentration isusually normal. These are mainlyattributed to the loss of a variety of plasma

proteins and minerals in the urine as wellas steroid therapy (4-10) . Most patientswith nephrotic syndrome also have renalfailure, so it may play a role in theabnormalities of calcium metabolism inthese patients, although these patients canshow calcium and vitamin D abnormalitieseven with normal Glumerular FiltrationRate (GFR) (10-12) .

As a result, children with idiopathicnephrotic syndrome are at risk formetabolic bone disease such as reducedBone Mineral Density (BMD) andabnormal bone histology, includingosteomalacia as well as excessive boneresorption resembling secondaryhyperparathyroidism. Early diagnosis andmanagement of these abnormalities, could

prevent the growth retardation and renalosteodystrophy that affects children withnephrotic syndrome (8, 10, 12-16) .

However, hypocalcemia may also lead toother neuromuscular (e.g. tetany),cardiovascular and mental disorders.Symptoms may range from mild (perioralnumbness, paresthesias, and musclecramps) to severe (carpopedal spasm,laryngospasm, and focal or generalizedseizures) (9) .So we conducted a literature review tohave a better perspective on the changes ofcalcium and vitamin D metabolism in

nephrotic syndrome and its consequenceson bones, along with the effect ofcorticosteroid therapy to provoke this

phenomenon, and possible preventivestrategies that could be done to avoid longterm outcomes in children.

Materials and Methods

The NCBI and Scopus databases wereused to search for information on this

matter between January 1970 to January2015. Relevant articles in English withspecific interest in " Calcium " and"Vitamin D " status in " NephroticSyndrome " were reviewed. References ofsuch articles generated also enabledwidening the reference pool.

Literature review

Data regarding alteration in calcium andvitamin D metabolism in patients withsteroid sensitive NS are conflicting andscarce. Although the onset of renalinsufficiency may contribute, theseabnormalities in calcium and vitamin Dlevels may be found in patients with NSand normal renal function (6, 7, 10, 12, 16-18) . Hypocalcemia seems to be a commonfeature in NS patients (9, 10, 18, 19) ;although some studies reported normalserum calcium levels (7, 11, 12) .

-

7/25/2019 Cacium and Vitamin D in Nefrotic Syndr

3/7

Esmaeeili et al.

Int J Pediatr (Supplement.1), Vol.3, N.2-1, Serial No.15, March 2015 105

In a study conducted by Thomas et al. in1998 nephrotic syndrome, was amongsignificant univariate predictors ofhypovitaminosis D (20) . The Plasmaconcentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D[25(OH) D] is low in patients with NS

because of a loss of vitamin D-binding protein in the urine (7, 8, 11, 12, 16, 18) .1,25(OH)2D levels, which shares the same

plasma binding protein, have been foundto have decreased (6, 7, 21, 22) or to have

been unchanged (8, 11, 12, 18) in patientswith nephrotic syndrome. Majority of the

previous studied showed that despite low

ionized serum calcium and histologicalevidence of secondaryhyperparathyroidism hyperparathyroidismin some patients, PTH levels are notconsistently elevated in NS patients (6-8, 11, 12, 16-19) .

Increased blood immunoreactive parathyroid hormone (iPTH) levels werereported in rare number of studies(6,17,18) . The apparent conflicting resultsin iPTH and serum ionized calcium valuesmay be related to differences in patient

populations or differing conditions underwhich the measurements were made.Serum phosphorus concentration wasnormal in most of the studies conducted onthese patients (10-12,17, 19) .

Histological bone alterations in these patients has also been reported, although inthe presence of normal or low calciumlevels (10,13,19,23) . In contrast, some

patients with elevated PTH and reducedcalcium and vitamin D metabolites maydisplay normal or near-normal bonehistology on bone biopsy (11, 16, 24) .Although these changes may occur as aresult of the prolonged proteinuric state orreduced vitamin D levels as the majordeterminants, it is likely that additionalunknown factors may be operating in thisgroup of patients. Furthermore, thefrequent use of corticosteroid therapy may

be associated with osteoporosis in childrenwith NS (11) .

Osteoporosis is a well known serious sideeffect of long-term treatment withglucocorticoids. GlucoCorticoids (GCs)are associated with decreasedgastrointestinal calcium absorption andincreased urinary calcium excretion bydecreasing its reabsorption in the renaltubule, resulting in a negative calcium

balance.

Furthermore, GCs stimulate boneresorption directly by enhancing osteoclastactivity and indirectly via increasing

parathormone (PTH) production.Glucocorticoids also inhibit osteoblasts

through reduction of osteoblastdifferentiation and increasing apoptosis ofthe mature osteoblasts resulting in reducein reduce the total number of osteoblasts,and an inhibition of the synthesis ofosteoid by these cells, which results insignificant reductions in bone formation(2, 4, 13, 14, 24,25) . Reduced BoneMineral Content (BMC) also has beenreported in short term, high doseapplications of GCs (26, 27) .

Osteoporosis is of particular concern ingrowing children who underwent longterm steroid therapy. During childhood and adolescence, skeletal changes result inincreases in bone dimensions and density.Children therefore seem to be vulnerableto adverse glucocorticoid effects on boneformation, leading to possiblecompromises in peak bone mass (24, 28) . Steroid-dependent minimal-change

nephrotic syndrome that originates inchildhood can persist after puberty in>20% of patients. These patients requireimmunosuppressive treatment duringseveral decades of their life. Also 30% ofthese children develop a frequentlyrelapsing course (3) . However, childrenmay display preserved bone mineral masseven shortly after the cessation ofintermittent high dose glucocorticoidtherapy, suggesting the capability of theyoung skeleton to rapidly regain previoussteroid-induced bone losses (29) .

-

7/25/2019 Cacium and Vitamin D in Nefrotic Syndr

4/7

Calcium and Vitamin D Metabolism in Pediatric Nephrotic Syndrome

Int J Pediatr (Supplement.1), Vol.3, N.2-1, Serial No.15, March 2015 106

Studies have demonstrated defective bonemineralization and an inverse correlation

between the administered dose ofcorticosteroid therapy and bone formationrates in bone biopsies of children with NS(3, 14, 15, 30, 31) . Although others foundno difference in bone mineral content inchildren receiving corticosteroidscompared with those who were off steroids(29) . These discrepancies may beattributed to variations in the number andage of the studied patients, duration of thedisease, steroid dose and the methodologyused to assess the laboratory markers of

bone metabolism. These findings indicatethe need for further studies regarding the prevention of steroid-induced osteoporosisin children. Although long duration ofsteroid therapy in children with nephroticsyndrome may increase the risk forosteoporosis, the long-term outcome ofthis chronic disease is favorable (2, 3) .

Some of the detrimental bone effectswhich seems to be because ofglucocorticoids, may be caused by theunderlying inflammatory disease. Forexample, inflammatory cytokines that areelevated in chronic disease, such as tumornecrosis factor, suppress bone formationand promote bone resorption throughmechanisms similar to glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (24) . The accuratecharacterization of glucocorticoid anddisease effects on skeletal development isnecessary to identify and evaluate targetedtherapies to optimize skeletal architectureand peak bone mass (24) . Mohamed et al.reported that, the significant decrease ofmarkers of bone formation and theincrease of the marker of bone resorptionin newly diagnosed patients with NS, priorto GC therapy, as compared with controls,may point to the significant role of therenal disease itself in the abnormality of

bone metabolism in NS (4) . Gulati et al.

also mentioned that biochemicalderangements caused by the renal diseaseitself is one of the important leadingcauses of metabolic bone disease in NSand GC is not the only factor responsiblefor osteopenia (32) .

According to review done by Mohamed etal., other factors that may contribute toresorption include nutritional deficiency,hypoproteinemia, immobilization, and

proinflammatory cytokines excessively produced in active inflammation, whichtriggers excessive osteoclastic activity (4) .There are few studies to date which has

evaluated the role of vitamin D andcalcium supplements in NS patients. It islikely that these children will fail toachieve their peak bone mass, which is akey determinant of the lifetime risk ofosteoporosis and are at risk for fractureslater on during their lifetime. Osteoporosis

prevention is best achieved by optimizinggains in bone mineral throughoutchildhood and adolescence (13) .

Because replacement therapy is simple andreduces the risk of fractures, anunderstanding of the importance ofsupplement therapy in childhood NS is of

particular importance (20) .

Some studies has been reported thatsupplementation with calcium and vitaminD is beneficial in preventing bone loss (10, 13, 26) . The treatment with a high dose ofvitamin D3 may correct the abnormalities,which suggests vitamin D3 should be usedin children with protracted active NS (18) .Sedman et al. suggested that children with

-

7/25/2019 Cacium and Vitamin D in Nefrotic Syndr

5/7

Esmaeeili et al.

Int J Pediatr (Supplement.1), Vol.3, N.2-1, Serial No.15, March 2015 107

hypercalcemia with hypercalciuria andnephrocalcinosis (33, 34) .

Despite all these evidence, some studies

studies have been suggested that increasein serum calcium levels cannot be affected by calcium and vitamin Dsupplementation (35) and its primarily dueto disease remission after steroid therapyand good management of NS patients leadsto improved serum calcium levels, with orwithout supplementation (9, 36) . On theother hand supplementation may increaseserum levels of calcium or vitamin D, butit wont necessarily reduce the risk for low

BMD (10, 13) .Steroid induced osteoporosis could be

prevented by administration of a bisphosphonate, such as risedronate. So in patients with NS receiving steroids,administration of a bisphosphonate might

be advisable (25, 37) ; although evidenceconcerning these issue are not quiteconcluding.

Conclusion

In summary changes in levels ofcalcium and vitamin D metabolites in

patients with NS are considered to befollowing urinary losses of thesemetabolites or their carrier proteins orsecondary to corticosteroid therapy,especially in long term therapeuticcourses; but the exact biochemical basisfor these changes remains speculative.Because of the potential adverse effects of

calcium and vitamin D deficiency on theskeleton and other organ Systems of NS patients, especially among growingchildren, widespread screening for vitaminD deficiency or routine vitamin Dsupplementation should be considered.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the belovedstuff and professors of pediatricnephrology department of Dr. SheikhHospital of Mashhad University of

Medical Sciences, for their assistance inthis manuscript and we offer our specialthanks to Dr. Yalda Ravanshad. This studywas supported by a grant from the vicechancellor for research of the MashhadUniversity of Medical Sciences for theresearch project as a medical student thesiswith the approval number ID: 920675.

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

1. Filler G. Treatment of nephrotic syndrome inchildren and controlled trials. Nephrology,dialysis, transplantation : official publicationof the European Dialysis and TransplantAssociation - European Renal Association2003;18 (Suppl 6):vi75-8.

2. Niaudet P. Long-term outcome of childrenwith steroid-sensitive idiopathic nephroticsyndrome. Clinical journal of the AmericanSociety of Nephrology : CJASN2009;4(10):1547-8.

3. Kyrieleis HA, Lowik MM, Pronk I, CruysbergHR, Kremer JA, Oyen WJ, et al. Long-termoutcome of biopsy-proven, frequentlyrelapsing minimal-change nephrotic syndromein children. Clinical journal of the AmericanSociety of Nephrology : CJASN2009;4(10):1593-600.

4. Mohamed GB, Abdel-Latif EA. Serumosteoprotegerin (OPG) in children with

primary nephrotic syndrome. Saudi journal ofkidney diseases and transplantation : anofficial publication of the Saudi Center forOrgan Transplantation, Saudi Arabia2011;22(5):955-62.

5. Harris RC, Ismail N. Extrarenal complicationsof the nephrotic syndrome. American journalof kidney diseases 1994;23(4):477-97.

6. Goldstein DA, Haldimann B, Sherman D, Norman AW, Massry SG. Vitamin DMetabolites and Calcium Metabolism inPatients with Nephrotic Syndrome and NormalRenal Function*. The Journal of ClinicalEndocrinology & Metabolism 1981;52(1):116-21.

7. Lambert PW, De Oreo PB, Fu IY, KaetzelDM, Von Ahn K, Hollis BW, et al. Urinary

-

7/25/2019 Cacium and Vitamin D in Nefrotic Syndr

6/7

Calcium and Vitamin D Metabolism in Pediatric Nephrotic Syndrome

Int J Pediatr (Supplement.1), Vol.3, N.2-1, Serial No.15, March 2015 108

and plasma vitamin D< sub> 3metabolites in the nephrotic syndrome.Metabolic Bone Disease and Related Research1982;4(1):7-15.

8. Freundlich M, Bourgoignie JJ, Zilleruelo G,Jacob AI, Canterbury JM, Strauss J. Bonemodulating factors in nephrotic children withnormal glomerular filtration rate. Pediatrics1985;76(2):280-5.

9. Dasitania V, Chairulfatah A, Rachmadi D.Effect of calcium and vitamin Dsupplementation on serum calcium level inchildren with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome.Paediatrica Indonesiana 2014;54(3):163.

10. Lisa C, Julia M, Kusuma PA, Sadjimin T. Riskfactors for low bone density in pediatricnephrotic syndrome. Paediatrica Indonesiana2011;51(2):61.

11. Mittal SK, Dash SC, Tiwari SC, Agarwal SK,Saxena S, Fishbane S. Bone histology in

patients with nephrotic syndrome and normalrenal function. Kidney international.1999;55(5):1912-9.

12. Panczyk-Tomaszewska M, Adamczuk D,Kisiel A, Skrzypczyk P, Przedlacki J, Gorska

E, et al. Markers of bone metabolism inchildren with nephrotic syndrome treated withcorticosteroids. Advances in experimentalmedicine and biology 2015;840:21-8.

13. Gulati S, Sharma RK, Gulati K, Singh U,Srivastava A. Longitudinal follow-up of bonemineral density in children with nephroticsyndrome and the role of calcium and vitaminD supplements. Nephrology, dialysis,transplantation : official publication of theEuropean Dialysis and Transplant Association

- European Renal Association2005;20(8):1598-603.

14. Freundlich M, Alonzo E, Bellorin-Font E,Weisinger JR. Increased osteoblastic activityand expression of receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand in nonuremic nephroticsyndrome. Journal of the American Society of

Nephrology : JASN. 2005;16(7):2198-204.

15. Lettgen B, Jeken C, Reiners C. Influence ofsteroid medication on bone mineral density in

children with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatric Nephrology 1994;8(6):667-70.

16. Tessitore N, Bonucci E, Dangelo A, Lund B,Corgnati A, Valvo E, et al. Bone histology andcalcium metabolism in patients with nephroticsyndrome and normal or reduced renalfunction. Nephron 1984;37(3):153-9.

17. Freundlich M, Bourgoignie JJ, Zilleruelo G,Abitbol C, Canterbury JM, Strauss J. Calciumand vitamin D metabolism in children withnephrotic syndrome. The Journal of pediatrics.1986;108(3):383-7.

18. Huang JP, Bai KM, Wang BL. Vitamin D andcalcium metabolism in children with nephrotic

syndrome of normal renal function. Chinesemedical journal 1992;105(10):828-32.

19. Koan C, Ayar G, Orbak Z. Effects of steroidtreatment on bone mineral metabolism inchildren with Glucocorticoid-sensitive

Nephrotic Syndrome. West Indian MedicalJournal 2012;61(6):627-30.

20. Thomas MK, Lloyd-Jones DM, Thadhani RI,Shaw AC, Deraska DJ, Kitch BT, et al.Hypovitaminosis D in medical inpatients. The

New England journal of medicine

1998;338(12):777-83.21. van Hoof HJ, de Sevaux RG, van Baelen H,

Swinkels LM, Klipping C, Ross HA, et al.Relationship between free and total 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in conditions of modified

binding. European journal of endocrinology /European Federation of Endocrine Societies2001;144(4):391-6.

22. Grymonprez A, Proesmans W, Van Dyck M,Jans I, Goos G, Bouillon R. Vitamin Dmetabolites in childhood nephrotic syndrome.

Pediatric Nephrology 1995;9(3):278-81.23. Hegarty J, Mughal MZ, Adams J, Webb NJA.

Reduced bone mineral density in adults treatedwith high-dose corticosteroids for childhoodnephrotic syndrome. Kidney international2005;68(5):2304-9.

24. Leonard MB. Glucocorticoid-inducedosteoporosis in children: impact of theunderlying disease. Pediatrics 2007;119 Suppl2:S166-74.

-

7/25/2019 Cacium and Vitamin D in Nefrotic Syndr

7/7

Esmaeeili et al.

Int J Pediatr (Supplement.1), Vol.3, N.2-1, Serial No.15, March 2015 109

25. Takei T, Itabashi M, Tsukada M, Sugiura H,Moriyama T, Kojima C, et al. Risedronatetherapy for the prevention of steroid-inducedosteoporosis in patients with minimal-change

nephrotic syndrome. Internal medicine(Tokyo, Japan). 2010;49(19):2065-70.

26. Choudhary S, Agarwal I, Seshadri MS.Calcium and vitamin D for osteoprotection inchildren with new-onset nephrotic syndrometreated with steroids: a prospective,randomized, controlled, interventional study.Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany)2014;29(6):1025-32.

27. Feber J, Gaboury I, Ni A, Alos N, Arora S,Bell L, et al. Skeletal findings in childrenrecently initiating glucocorticoids for thetreatment of nephrotic syndrome. OsteoporosisInternational 2012;23(2):751-60.

28. Wasilewska A, Rybi-Szuminska A, Zoch-Zwierz W. Serum RANKL, osteoprotegerin(OPG), and RANKL/OPG ratio in nephroticchildren. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin,Germany) 2010;25(10):2067-75.

29. Leonard MB, Feldman HI, Shults J, Zemel BS,Foster BJ, Stallings VA. Long-term, high-doseglucocorticoids and bone mineral content inchildhood glucocorticoid-sensitive nephroticsyndrome. New England Journal of Medicine2004;351(9):868-75.

30. Fujita T, Satomura A, Hidaka M, Ohsawa I,Endo M, Ohi H. Acute alteration in bonemineral density and biochemical markers for

bone metabolism in nephrotic patientsreceiving high-dose glucocorticoid and one-cycle etidronate therapy. Calcified tissueinternational 2000;66(3):195-9.

31. Olgaard K, Storm T, Wowern NV, DaugaardH, Egfjord M, Lewin E, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in the lumbar spine, forearm,and mandible of nephrotic patients: a double-blind

study on the high-dose, long-term effects of prednisone versus deflazacort. Calcified tissueinternational 1992;50(6):490-7.

32. Gulati S, Godbole M, Singh U, Gulati K,Srivastava A. Are children with idiopathicnephrotic syndrome at risk for metabolic bonedisease? American journal of kidney diseases2003;41(6):1163-9.

33. Sedman A, Friedman A, Boineau F, Strife CF,Fine R. Nutritional management of the childwith mild to moderate chronic renal failure.The Journal of pediatrics 1996;129(2):s13-8.

34. Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA,Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al.Evaluation, treatment, and prevention ofvitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Societyclinical practice guideline. The Journal ofClinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.2011;96(7):1911-30.

35. Wojnar J, Roszkowska-Blaim M, Panczyk-Tomaszewska M. [Dynamics of bone biochemicalmarkers in nephrotic children treated with

prednisone and metabolites of vitamin D].Przeglad lekarski 2007;64(9):552-8.

36. Banerjee S, Basu S, Sengupta J. Vitamin D innephrotic syndrome remission: a case-controlstudy. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany)2013;28(10):1983-9.

37. Kim SD, Cho BS. Pamidronate therapy for preventing steroid-induced osteoporosis inchildren with nephropathy. Nephron Clinical

practice 2006;102(3-4):c81-7.