By J DECKER FORREST and JOSHUA...

Transcript of By J DECKER FORREST and JOSHUA...

SATURDAY 25 NOVEMBER 2006

EARLY on Saturday morning, we accompanied Angus MacKenzie of Gearraidh Bhailteas to Cill Donain

machair to help feed the cattle. Once back, we telephoned several inform-

ants to arrange meetings later in the day or the next day. We called George MacKinnon in Loch Baghasdail to enquire about an interview, and a time was set for Sunday. We phoned Angus Johnstone to ask after the whereabouts of his father, Neil, a former pupil of Bob Nicol’s local classes who has long been active in the South End Piping Club. We were told that Neil would probably be out renovating his new house in Dalabrog. We would catch him there if he was not back in his current home on Caismir Place.

We drove to the south end of Uist to call upon Neil Johnstone and Gilbert Walker in Dalabrog, and Calum MacAulay in Loch Baghasdail.

We first stopped by the post office in Da-labrog run by Gilbert and Margaret Walker. Gilbert was out, but Margaret suggested we come to the house later that evening.

We next called on Neil Johnstone on Caismir Place. He and his wife had just arrived home from working on their new house and Neil’s hand was slightly injured from an incident on the roof. He paid it no mind, however, and im-mediately sat us down for a yarn and a dram.

Neil spoke of the use of cuilc in the making of reeds for drones and (less certainly) pipe chanters. This involved soaking the raw cane in a solution, the nature of which he could not recall, prior to cutting and shaping. He could not recall the reason for this treatment. He said, however, that the treatment was used irrespective of the type of reed being made: drone or chanter.

He described practice chanter reeds being made of eòrna (barley straw) that was harvested in early autumn. Cuilc was harvested locally around November for the thatching of local dwellings. In effect, piping was seasonal, with

“more piping being done in autumn and winter than in spring and summer”. He emphasised at this point that nothing was wasted in Uist; due to the relative poverty and scarcity of materials, everything was put to some use or another.

He also recalled a practice chanter made from the wood of a chair leg played by a child in his youth at a local chanter class. Like the relic in the possession of the ‘King of Jigs’, the late Aonghus beag Dhòmhnaill ‘ic Fheargais, the chanter had no top chamber or mouthpiece and was simply blown with lips over reed. This accorded with many reminiscences on local chanter-making; apparently the top chamber was in the main considered superfluous.

Decker demonstrated the two styles of jig-playing applied to the tune Paddy’s Leather Britches which we had used in past interviews: the accented, strathspey-like style as performed by Angus MacAulay in his c.1950 commercial recording, and the even or rounded style often heard in competition today. Neil considered the accented style more reflective of early competi-tion performance, and the rounded style more for dancing. He commented that the “King of Jigs” used to play both styles: “a piper who could play in both tastes”.

Neil also commented that jigs were in earlier years often associated with fairies and fairy knolls. The corollary was that jigs were often considered “playful” or “happy” music, and he made a direct link between jigs and the danc-ing of fairies. He went on to comment on fairy lore associated with Pìobairean Smerclait, or the Smearclait Pipers.

Neil, a multi-instrumentalist, spoke at some length about playing the accordion during his career in the Merchant Navy. He described his experience with “mixed crews” versus “island crews” (e.g. Barra crews or Lewis crews) and how one had to be careful not to offend other nationalities or creeds among the mixed crews. He contended that accordion music was more to the tastes of other nationalities among mixed crews than was the music of the pipes.

He obtained a piano accordion while he was with his ship in Italy. He had had some

PIPING TODAY • 26

Piping in South Uist and BenbeculaA RESEARCH JOURNAL, 21-27 NOVEMBER 2006

By J DECKER FORREST and JOSHUA DICKSONLast of 3 parts

FROM 21 to 27 November, 2006, J Decker Forrest and Joshua Dickson — both mem-bers of staff active in Scottish music and research at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama — toured South Uist and Benbecula in pursuit of sources both new and familiar. It was a chance to catch up with long-time colleagues in the chroni-cling of change and tradition in the area (whether to revisit past lines of enquiry or to follow new ones) and to search for sources of seanchas — oral history, personal reminiscence, the inside scoop — hereto-fore overlooked.

This was not the first trip to Uist for either Josh or Decker: Josh spent much time there researching his doctorate in Scottish ethnology, culminating in the book When Piping Was Strong (2006); Decker began researching piping in Uist several years ago and has close family connec-tions to the area.

They arrived in Uist with a number of re-search objectives for the week. Decker was, in the main, interested in the material culture asso-ciated with piping in Uist and Benbecula, such as the indigenous manufacture of practice chanters and reeds for both chanter and drone. Josh was mainly focused on biographical and performance information relating to Lachlan Bàn MacCormick (1859-1952), whose life spanned a great deal of change in the Hebridean tradition. Both were also interested in light music performance style and surviving Gaelic nomenclature for tunes, technical words and instrument materials. In addition, Decker was keen to investigate the use of the truimpe, or jew’s harp, in Uist and Benbecula.

What follows is a day-by-day account of their work and travels during the week in question. The notes on which it is based were composed at the end of each day as a way of allowing them to reflect on the day’s work, consider the significance or otherwise of this or that, and generally improve recall of interviews that may or may not have been voice-recorded. This is considered an essential plank of ethnographic or journalistic research of any sort. The authors hope that this account will therefore serve as an example to other pipers, or scholars of piping, who wish to investigate further the as yet unexhausted contribution of Gaelic oral history to our understanding of piping’s place in Scottish music.

UIS

T

WILLIE WALKER in Lovat Scouts uniform at the Askernish Games, c.1930-31. Photo: courtesy of the late Dr Margaret Fay Shaw Campbell of Canna

PIPING TODAY • 27

UIS

T

experience with the button accordion, or melodeon, in Uist some time beforehand and was able to take up the piano accordion more or less on his own aboard ships. He did not read music specifically for the accordion and recalled simply playing tunes borrowed from the pipe repertoire.

We stayed some time longer to play a few tunes on the pipes for Neil and his wife. Decker showed his replica Donald MacDonald chanter to Neil, who voiced appreciation for its work-manship and tone.

We then visited the ruins of the home of the late John (Seonaidh Roidein) MacDonald in Da-labrog. We cautiously explored the house inside and out, including an older dwelling adjacent to the main house that we took to be the home of John’s father, Dòmhnall Bàn Roidein.

John’s house had caught fire in the mid-1980s, after which John stayed at Daliburgh House until his death in 1988. Neil Johnstone recalled that John had been asleep at the time the fire started, and that John’s pipes had per-ished in it. Only the silver ferrules and mounts had survived, albeit burnt and twisted from the heat.

We had a tangible sense that the ruins of the legendary piper’s home represented hallowed ground. The house looked as ancient as an old black house, and yet — looking at the state of the burnt roof beams, fireplace and remaining furniture — the fire could to all appearances have taken place just last week. After taking some photographs of the interior and exterior, we moved on.

WE then drove to Loch Baghasdail Hotel to call upon its proprietor, Calum MacAulay. Calum is a nephew of the late Angus MacAulay of Benbecula.

We showed Calum photographs we had scanned earlier in our fieldwork, including a photo of an unidentified, moustachioed piper in Lovat Scouts’ uniform whom we suspected was Angus. Calum could not positively iden-tify the piper, but he believed that it was not Angus.

We played the commercial recordings of Angus playing a set of jigs for Calum, including Paddy’s Leather Britches and a jig he had made himself, David Ross. Calum could not offer any useful commentary on the performance style, but was interested and intrigued to hear such good quality recordings of his uncle.

Calum explained his family tree thus:

CALUM identified two piping relatives of Angus: Peter MacLean in New Zealand, and Iain MacAulay, now living in Spain. Peter now owns and plays Angus’s pipes. Iain was a well-regarded piper who had learned much directly from Angus and would be able to comment on Angus’ performance style first hand.

After visiting Calum in Loch Baghasdail, we drove back to Gearraidh Bhailteas. We had some late lunch, did a bit of piping and visited the MacKenzies across the road to give an ac-count of the day’s activities.

At this stage, we telephoned Peter (Peadar Ghighat) Campbell in Iochdar. Peter’s father was Angus Campbell, the ‘Gighat’ mentioned earlier.

We made arrangements to visit Peter for an interview the following day.

We arrived in Dalabrog to pay a visit to Gilbert Walker at his home adjacent to the post office.

Gilbert did not recall seeing or hearing of chanters being made in Uist. However, he and other pipers made practice chanter reeds from eòrna. He confirmed the usual practice of cut-ting a suitable sized piece, chewing the end and inserting the unchewed end into the chanter. He claimed that these reeds would typically last at least two weeks.

Gilbert’s first cousin, Morag Cummings (nee MacIntyre) is a daughter of the late Donald Ruadh MacIntyre, the Paisley Bard. She had spoken recently on the radio, recalling that her father had mentioned making drone reeds from cuilc.

As noted by other informants, most piping took place in winter, since reed-making was a by-product of the harvest season.

Gilbert spoke of his piping experience with the Lovat Scouts for a period of 18 months, after which he did not continue to play. He explained how he had been taught, originally by his uncle, William Walker, who also had piped for the Lovat Scouts. He recalled using Logan’s Tutor at this time.

Willie Walker was taught originally by Niall Eirig MacKay (Neil son of Effie), a Pipe Major

in the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders or Lovat Scouts. He lived in a shack near the Da-labrog poor house, which is where the council houses currently stand.

Apparently, there had been no pipers among the Walkers before Willie; Gilbert said that Willie had “got his piping” through his moth-er’s people (not that his maternal relatives had taught him to play; rather that his talent, his aptitude, for piping had been inherited from his mother’s side of the family). Gilbert’s testimony illustrates the surviving Gaelic attitude to the inheritance of musical ability.

Willie’s mother was Catriona Campbell. This may have been a sister of Neil (Niall Chatrìona) Campbell, the well-known Frobost piper, al-though this is not for certain. According to Joan Martin, Willie Walker and Findlay Martin once played for a wedding dance at Garrynamonie School wearing Lovat Scouts uniforms.

Gilbert showed us a photograph of the Lovat Scouts’ band c.1942-3 taken in Vancouver, Canada: the regiment was in Canada for ski training in the Rocky Mountains at the time. The photo was framed and mounted, but Gilbert graciously removed the frame to allow us to scan it. Gilbert claimed the band was noted as the best pipe band in the British Army at the time.

Gilbert then produced a jew’s harp, or tru-impe, during the interview, commenting that this instrument was present “in every house at one time”, much like a practice chanter or a set of pipes. The specimen he showed us was of modern Austrian manufacture with angled flukes. Gilbert claimed that earlier jew’s harps were shaped in a more rounded fashion.

Gilbert played several tunes on the jew’s harp. His articulation was extremely clear and lively. He played by striking the lamella in a hand-backward motion, using the tip of the middle finger of the right hand. He tapped his right heel heavily when playing.

He played three tunes, the first two of which have Irish associations. The first was Saddle the Pony, an old traditional Irish quickstep, in a slight dot-cut rhythm. He played two parts at around 105 beats per minute. The second tune

Figure 1.

John Roderick Donald Mary Sheila Angus

Iain (piper), Sheila Margaret

Mary Donald George Calum Peter MacLean (piper)

PIPING TODAY • 28

UIS

T

UIS

T

he played was Piper’s Cave, another quickstep. He played only one part, again around 105 bpm. Finally, he played the traditional High-land reel High Road to Linton in two parts. Gilbert tossed the truimpe onto the coffee table upon completion of each tune.

He claimed to play mainly marches and reels, but very rarely for dancing. He recalled playing the truimpe at the Ceòlas festival one year, and a Cape Breton girl step-danced to his tunes. That was the only occasion he can recall. He never heard of anyone dancing to it traditionally.

We spoke briefly of jigs, and of old and cur-rent performance styles. Angus ‘King of Jigs’ MacDonald’s name was once again invoked with nostalgic reverence. Gilbert recalled his mother once saying she would go the Askernish games just to hear Angus play jigs.

SUNDAY 26 NOVEMBER 2006ON Sunday morning, we attended mass with the MacKenzies at Bornish Church. Father Michael announced celebrations planned on the occasion of the community buy-out of South Uist. The events would include piping by John Angus Smith, James MacPhee, Iain and Dr Angus MacDonald of Glenuig, the South Uist Pipe Band and the White Rose Ceilidh Band. Some noted with regret that few Uist-born pipers were invited to take part.

After breakfast, we started off for Loch Eynort. There we met John Alec MacDonald, known locally as “Black Joe”, at his home. Black Joe is not a piper, but he took up the chanter briefly as a child and is said to be extremely knowledgeable of local history. His father died in a fishing boat accident in Loch Eynort when Black Joe was about nine months old. His mother remarried.

Black Joe recalled that his step-father, Neil MacIntosh, once made a practice chanter with no top chamber or mouthpiece. He did not recall how MacIntosh made it, but said he might have made it from bamboo, with a red hot wire thrust through. This method of boring, and the construction without a mouthpiece, was consistent with previous descriptions we encountered in Uist. He also confirmed the making of practice chanter reeds with eòrna or corca mór.

Black Joe recalled taking chanter lessons at Loch Eynort school from Donald John (Dòmhnall Iain) Morrison, Louis Morrison’s father. Black Joe would have been 10 or 11 years old at the time. He said that all of the

students in Donald John’s class were made to obtain practice chanters from Henderson’s in Glasgow, and that reeds came with them. Black Joe’s first tune was a march called Kiloran Bay, indicating in all probability the use of Pipe Major Willie Ross’s Book 3 at the time.

After this brief experience, he left for secondary school in Dalabrog and did not continue with the chanter.

We enquired about the jew’s harp. Black Joe thought he may have seen one once; noth-ing more than that. Coupled with a scarcity of the jew’s harp in Gearraidh Bhailteas, this suggests that the instrument was popular in some localities and not in others. Though its use generally throughout the Hebrides in the past cannot be denied, it is interesting to note the discrepancy between localities in our travels of Uist so far. It may simply be a question of access: in Dalabrog, where it was a popular pastime, the jew’s harp could be bought from the local shop; at Loch Eynort and other smaller townships, one had to make do with a mobile grocery van or, in earlier times, small village shops run out of local houses that stocked only bare essentials.

After our talk with Black Joe, we crossed the garden to call on his sister, Joan Anderson, and her husband Donald. They live in the old Loch Eynort schoolhouse adjacent to Black Joe’s house. Donald is a piper and a collector

of musical instruments and historical texts. He was taught originally by William Melvin while living in England.

Donald spoke broadly about his ideas on piping development and performance style.

Joan (b. 1937) had vivid memories of piping in Loch Eynort and elsewhere in Uist when she was about 15-16 years of age. She recalled pipers making their own practice chanter reeds. She was not encouraged to learn piping, but learned to play the chanter on her own using her brother’s chanter, right hand top. She similarly taught herself to read music at that time. However, she felt that by learning to play right hand top, she had learned incorrectly and decided not to continue further.

She recalled seeing a piper play at a dance in Staoineabrog or Cill Donain school with his back turned to the dancers. She described it as being quite normal. Angus MacKenzie later confirmed the customary nature of this behaviour insofar as piping in the Cill Donain and Gearraidh Bhailteas area was concerned.

We took our leave of the Andersons and drove to Loch Baghasdail, where we had arranged to meet George (Seòras Mór) MacKin-non and his wife Mary at their home.

George first learned to play from local Loch Baghasdail piper Adam Scott, and then from Willie Walker. His father played, but did not compete or teach, and was generally

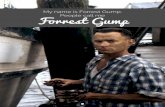

DECKER FORREST helps George MacKinnon tune his drones at George’s home in Loch Baghasdail, South Uist.

Phot

o: Jo

sh D

icks

on

PIPING TODAY • 29

UIS

T

UIS

T

speaking ear-learned and musically non-liter-ate. George recalled, however, that he played in a “conventional” style, i.e. with correct modern fingering.

George learned by notation; primarly from Logan’s Tutor. His first tune was The 79th’s Farewell to Gibraltar. He first competed at the Askernish games 55 years ago (c.1951) in the junior practice chanter event. The event was an MSR and he recalled compet-ing barefoot.

On the subject of jigs, George spoke of Angus MacDonald of Gearraidh Bhailteas, Aonghus Beag Dhòmhnaill ‘ic Fheargais — the

WE then drove to Iochdar to interview Peter ‘Ghighat’ Campbell. Peter did not know the origin of the name ‘Gighat’. His father Angus, ‘the Gighat’, was a well-respected piper for dances in the north of the island.

The Gighat was entirely ear-learned and could not read music. He had taught himself, and had always played sitting down. Peter recalled that this was out of choice rather than due to a medical condition. He would often sit on the broad windowsills of the local school-houses when playing and keep time with both heels in unison.

So far as Peter knew, the Gighat never owned a set of pipes, but rather played on sets belong-ing to other pipers at the ceilidh or dance, or who would come to the house.

Decker demonstrated the accented style of jig playing reflective of Angus MacAulay’s

‘King of Jigs’. George recalled a local anecdote concerning Angus: a piper asked him on the day of the games at Askernish machair if his pipes were in good order. Angus told the man that they certainly were, as he had submerged them in a burn the night before! We took this to be a gratifying example of the survival of tall tales in the Uist piping tradition.

Keen to learn more of local pipers’ thoughts on performance style, we demonstrated the two styles of jig-playing for George: the first, accented style taken from Angus MacAulay’s c. 1950 commercial recording, and the sec-ond an example of the rounded, even style

Figure 2. Arthur Bignold of Lochrosque March John MacColl

Figure 3. Arthur Bignold of Lochrosque As played by George MacKinnon (Loch Baghasdail) (Ross 1943:26)

heard often today. Of the two, the accented style reminded him more clearly of Angus MacDonald’s playing.

Decker, Josh and George then spent some time playing tunes on the pipes and perusing his music collections. He played several clas-sic competition tunes, such as Knightswood Ceilidh, Arthur Bignold of Lochrosque, Mag-gie Cameron and the jig Over to Uist. His rendering of Arthur Bignold was particularly musical, including a treatment of the sixth and seventh bars of each part that Josh had only seen written in manuscript paper among the notes (c 1952) of the late George Moss.

PETER CAMPBELL of Iochdar, South Uist,

shows Josh Dickson the 100 year-old Henderson

practice chanter that belonged to Peter’s late

uncle.

Phot

o: D

ecke

r Fo

rres

t

PIPING TODAY • 30

UIS

T

UIS

T

c. 1950 recording, and contrasted this with the more modern “even” treatment. Peter identifi ed the accented style with his father’s performance of jigs.

Peter recalled the use of eòrna for making practice chanter reeds. He did not recall the use of homemade chanters.

He referred us to Màiri Gotton, aged 93, and John MacLean, both in Iochdar, as good potential informants of Uist tradition past and present. John is one of the well known MacLean pipers from the area. He is a brother of James, in Glasgow, and Ronald in Inverness.

Peter showed us his uncle Duncan’s black-wood practice chanter, thought to be 100 years old, made by Peter Henderson in Glasgow. Peter’s uncle had died in Canada during the Second World War, and the chanter had been kept in the family ever since.

Luckily, we were able to scan two photos belonging to Peter’s family. The fi rst is a very blurred picture of the Gighat sitting in shirt

and tie with a teacup balanced on his knee. The second was taken at Ardkenneth Church in the early 1950s, apparently on the occasion of the Queen’s Coronation tour. Piping the royal party grandly outside the church are the Roidein brothers – John and Roderick.

We then retired for the evening to the Mac-Kenzies for dinner and a ceilidh.

After a few tunes and a modest dram, we said our heartfelt goodbyes to the MacKenzies and made our way back to “base camp”, where we made some fi nal notes on the evening and on the week at large.

MONDAY 27 NOVEMBER 2006 WE rose early on Monday morning to catch the ferry back to Oban. A storm was in full throt-tle. Although disconcerted by the lashing wind and rain that greeted us outside, we remained hopeful that the ferry would sail.

As we approached the Loch Baghasdail pier in our rental car, we were relieved to see the ferry

with gangway extended and its fl oodlights bath-ing us in a welcome glow. So far so good.

We rid ourselves of the rental and marched aboard. As Decker settled in, Josh stood by the main portal, watching the smaller vessels moored to the pier being battered by the waves. A grizzled crewman and a tall, smartly dressed man whom Josh took to be the captain stood nearby, speaking – worryingly – along the fol-lowing lines:

Captain: Nope. Naw. No way. We’re no getting out of here. Not gonnae happen. Not worth my life.

Crewman: Och I’ve seen worse than this.Captain: Aye, but I’m a young man yet. I’ve

got my whole life ahead o’ me. After the above exchange, it was with some

relief that Josh discovered that the “captain” was in fact a junior member of the galley staff. We soon left Loch Baghasdail — sadly not by steamer at midnight — behind, and lived to tell the tale. ●

M G R E E D SM c C a l l u m B a g p i p e s

M o o r f i e l d I n d . E s t a t eT r o o n R o a d , K i l m a r n o c k

A y r s h i r e , K A 2 0 B A

T e l . 0 1 5 6 3 5 2 7 0 0 2F a x . 0 1 5 6 3 5 3 0 2 6 0

e - i n f o @ m g r e e d s . c o mw - w w w . m g r e e d s . c o mw w w . m g r e e d s . c o m

Quality Reeds

Designed and made by Rory Grossart

MG REEDSHave you heard how good they are?

UIS

T

PIPING TODAY • 31