By Gwendolyn Lawrence. In June 2014, I traveled with my family to Svalbard, Norway, for a Lindblad...

-

Upload

sharon-sims -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

3

Transcript of By Gwendolyn Lawrence. In June 2014, I traveled with my family to Svalbard, Norway, for a Lindblad...

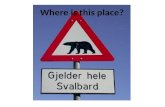

In June 2014, I traveled with my family to Svalbard, Norway, for a Lindblad Expedition onboard the National Geographic Explorer.

My journey to the Arctic Circle changed my view of the world around me, particularly of plants and animals. Before the trip, I thought of wildlife as big and majestic, or cute and cuddly.

On my expedition, I learned that not everything on this earth is how we expect it. I learned to look more closely at the environment and to pay attention to more details around me.

When you start to look closely at the world, there are a lot of exciting surprises!

Before my trip, I pictured whales as all being the same shape and all very similar to each other. However, I learned that different types of whales are quite different from each other. I came to be able to recognize different kinds of whales as they swam by our ship.

Beluga WhaleBeluga whales are a very interesting kind of

whale because they have no dorsal fin (the fin on top of a whale that helps them swim straight). When they chase fish, they are

shallow-water whales. They are able to swim right under the ice without bumping a dorsal fin

on the ice above.

Humpback WhaleHumpback whales are in a group of

whales that have no teeth; instead, they have baleen. Baleen is a brush-like or

bristle-like substance that helps them eat krill. They use their baleen to sift the water out, while keeping the krill in.

We saw humpback whales swimming with fin whales alongside our ship. Fin whales are larger than humpbacks. However, humpback whales dive deeper than fin whales, sometimes showing their fluke (tail) above the water as they dive. On the ship, we were very excited: whenever a whale would fluke, we would cheer! Birds like to follow around sea mammals because they eat the same foods. If the whales find food, so do the birds.

My mom and I were kayaking when we saw something bobbing on the waves. At first we thought it was a piece of trash because it was all black with a white

middle. As we rowed nearer, we looked closely and discovered it was a bird.

My mother photographed it. When we were back on the ship, I looked it up in my bird guide and found that it was an auk. Sometimes it was hard to identify so many different kinds of birds, but by paying close attention and using my bird

guide, I got the hang of it.

Some places on Earth do not appear as rich with life as other places. Before traveling to the Arctic Circle, I had been to the Galápagos and to the cloud forest in Ecuador, where it was noisy with life. But the Arctic Circle is very quiet. Usually our ears need to work hard to perceive the subtle sounds of Svalbard: the rustling of reindeer eating plants, polar bears padding across ice, the wind howling over ice floes.

One exception is the birds, which can make a lot of noise. The Arctic skua is a seabird, and so is the phalarope. The phalarope’s way of eating is interesting: it swims in circles and dips its beak into the water continuously, eating its prey. The Arctic tern is also fascinating—it flies like its name sounds: it turns very sharply in search of food.

On our expedition, fulmars were rare; we only saw them once. But we saw a lot of kittiwakes. We also saw a glaucous gull, as well as its nest. Glaucous gulls eat kittiwakes—and we even caught one glaucous in the act!

We were fortunate to witness a glaucous gull and a barnacle goose fighting under a huge rock. No one quite knew what they were fighting over. My first theory was that they were fighting over food. However, after thinking about it, I realized that they were fighting near the glaucous gull’s nest, so I am pretty sure the gull was defending its nest.

Because of the midnight sun in June, the birds

are busy nesting twenty-four hours a day.

The fox is attracted to the nesting cliffs because

it means that there is lots of prey for the fox.

We saw an Arctic fox by a rock face

that was covered with birds.

The Arctic fox often eats birds and birds’ eggs.

Unlike the fox, the reindeer is an herbivore. An herbivore eats only plants; an omnivore eats meat and plants; a carnivore eats only meat. When food gets scarce, reindeer eat lichen. Our Natural Geographic naturalist taught us a silly saying to remember what plants make up lichen: “Alice Algae and Fred Fungus took a ‘lichen’ to each other, but their relationship was on the rocks because Fred took Alice for ‘granite.’” This funny anecdote helps us remember that lichen grows on rocks and is made up of algae and fungus. Looking closely, we saw white reindeer hairs on the lichen because the reindeer had been shedding their winter coat to reveal their thinner brown summer coat.

On one excursion, after seeing reindeer, we spotted polar bear tracks in the mud. Once we were back on the ship, we realized there was a polar bear right around the bend!

Polar bears do not normally eat reindeer because reindeer can run really fast, but polar bears cannot because they would overheat.

Polar bears are sea mammals. They spend ninety-nine percent of their life on ice floes. Polar bears’ fur is hollow to trap warm air inside the hairs.

Male polar bears are more than twice the size of females. Usually females give birth to two cubs at a time, and take care of the cubs for two years. Polar bears can grow up to nine feet long and can weigh up to one thousand pounds.

In Svalbard, there are only about two thousand polar bears. We were lucky to see seven polar bears on our trip.

If there is no ice, polar bears can starve. Polar bears hunt pinnipeds, which are blubbery swimming mammals that include seals and walruses. The bearded seal is a member of the pinnipeds. Bearded seals are the largest seals in Svalbard. They grow to eight feet long and around seven hundred pounds. Bearded seals eat mostly shellfish, such as mussels and clams. They are named after their whiskers.

The walrus is a pinniped with impressive whiskers, too. In fact, walruses have hundreds of whiskers. Peering closely through binoculars, you can see the walruses move their whiskers individually or all together. They use their whiskers to find food. They eat mostly clams and cockles, but some will eat seals. They dive up to two-hundred-fifty feet. Male walruses weigh more than three thousand pounds, which is as much as a car, and are about eleven feet long. The tusks of male walruses measure about three feet long; the tusks of female walruses are approximately two feet long and are more slender than those of males. Walruses love ice; they use their tusks to pull themselves up onto ice. Walruses have one pup every two years.

The Atlantic Walrus

People hunted walruses heavily in the 1900s. At Kapp Lee on Edgeøya island, where we saw four male walruses resting on the beach after a long swim in the open waters, we also saw a vast walrus graveyard on the permafrost. In the twentieth century, walruses were hunted close to extinction. But today, thanks to new laws against walrus hunting, the walruses have made a dramatic comeback.

Plants can grow in surprising places in the Arctic—they can even grown in the Arctic desert. A desert is not necessarily a hot and sandy place; it is a place without a lot of water. The desert we visited on Svalbard had huge mounds of rocks, some sparse plant life, ice, and snow. We belly slid penguin-style down a mound of rocks that had layers of snow on it. We even had a snow fight and found a reindeer skull buried under ice.

Click icon to add pictureSome plants have taken refuge on carcasses and bones of slaughtered walruses.

Bending down low over the bones, we spied purple saxifrage (pictured here), nodding saxifrage, Svalbard poppy, net-leaved willow, Arctic buttercup, mosses, and lichen all growing in little mounds among the bones.

The mounds help flowers grow by giving all flowers a chance to catch sunlight.

I could not take the ammonite fossil back home with me, because it is important on an excursion to leave everything the way it is. However, I brought home my memory of the fossil as the most special of my many Arctic discoveries.

It was exciting to uncover the reindeer skull, but my most thrilling discovery of all was an ammonite fossil.

I was hiking across the Arctic desert, when something blue caught my eye. I thought this was strange because most of the rocks were yellowish or orange, but there was something blue on one of the rocks. I picked up the object and peered closely: it was a fossil! I brought it to the geologist, who identified it as the fossil of an animal called an ammonite. This fossil is probably around three hundred million years old. That means it is older than the dinosaurs!

My expedition to the Arctic Circle is the best trip I have ever taken. At first the Arctic appears vast, bleak, and barren.

But if you look closely and carefully, you…

My expedition to the Arctic Circle is the best trip I have ever taken. At first the Arctic appears vast, bleak, and barren.

But if you look closely and carefully, you…

DISCOVER!

The preceding project is the work of Gwendolyn Lawrence. All artwork, photographs, and text are by Gwendolyn.

Gwendolyn wanted to add this photo (taken by her mother) after the last project slide in order to show you her exciting find: Here is Gwendolyn in the Arctic desert with the three-hundred-million-year-old ammonite fossil she describes in her project. A thrilling discovery!