Chapter Twenty- Four: Aggregate Demand and Economic Fluctuations.

Business Fluctuations and the Theory of Aggregate Demand

-

Upload

anfal-aslam -

Category

Documents

-

view

37 -

download

3

Transcript of Business Fluctuations and the Theory of Aggregate Demand

BUSINESS FLUCTUATIONS AND THE THEORY OF

AGGREGATE DEMAND

Business FluctuationsThe lesson of Keynesian economics is that “changes in

aggregate demand can have a powerful impact on the overall level of output, employment, and prices in the short-run.

Upward and downward movements in output, inflation, interest rates, and employment form the ‘business cycle’ that characterizes all market economies.

Economic history shows that the economy never grows in a smooth and even pattern. A country many enjoy exhilarating economic expansion and prosperity (US in the 1990s), which may be followed by a recession or even a financial crisis or, on rare occasions, a prolonged depression.

Features of Business CyclesBusiness cycles are economy-wide fluctuations in total

national output, income, and employment, usually lasting for a period of 2 to 10 years, marked by widespread expansion or contraction in most sectors of the economy.

Economists typically divide ‘business cycles’ into two main phases, “recession” and “expansion”.

A “recession” is a recurring period of decline in total output, income, and employment, usually lasting from 6 months to a year and marked-up by widespread contractions in many sectors of the economy. A “depression” is a recession that is major in both scale and duration.

For example, the global economy is facing a recession these days.

A Business Cycle, Like the Year, Has Its Seasons

Characteristics of a Recession1. Often, consumer purchases decline sharply, while business

inventories of automobiles and other durable goods increase unexpectedly. As businesses react by curbing production, real GDP falls.

2. The demand for labour also falls. Initially, there is a drop in the average work week, followed by layoffs and ‘higher unemployment.

3. As output falls, inflation slows. As demand for materials decline, their prices tumble. Wages and prices of services are unlikely to decline, but they tend to rise less rapidly in economic downturns.

4. Business profits fall sharply in recessions. In anticipation of this, common stock prices usually fall as investors sniff the scent of a business downturn. However, because the demand for credit falls, interest rates generally also fall in recessions.

Expansions are the mirror images of recessions, with each of the above factors operating in the opposite direction.

Business Activity in the US Since 1919

Business Cycle TheoriesEconomists explain business cycles under two categories

namely “Exogenous and Internal Mechanisms”. The ‘exogenous theories’ find the root of the business

cycle in the fluctuations of factors outside the economic system like in wars, revolutions, and elections; in oil prices, gold discoveries, and migrations; in discoveries of new lands and resources; in scientific breakthroughs and technological innovations; even in sunspots or the weather.

For example, the long economic boom of the 1990s was fueled by an ‘investment boom’ radiating out of the information technologies sector and largely based on fundamental scientific and engineering developments in microprocessors.

Business Cycle Theories (contd.)

By contrast, the “internal theories” look for mechanisms within the economic system itself that give rise to self-generating business cycles.

In this approach, every expansion breeds recession and contraction, and every contraction breeds revival and expansion, in a quasi-regular, repeating chain.

For example, according to the “The Multiplier-Accelerator Theory”, rapid output growth stimulates investment. High investment in turn stimulates more output growth, and the process continues until the capacity of the economy is reached, at which point the economic growth rate slows. The slower growth in turn reduces investment spending and inventory accumulation, which tends to send the economy into recession. The process then works in reverse until the “trough” is reached, and the economy then stabilizes and turns up again.

Business Cycle Theories (contd.)Demand-Induced Cycles: One important source of

business fluctuations is ‘shocks to aggregate demand’.

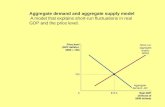

For example, a typical case is illustrated in Figure 23-4, which shows how a ‘decline in aggregate demand’ lowers output.

In the figure, the economy is in a short-term equilibrium at point ‘B’. Then because of a decline in defence spending or tight money, the aggregate demand curve leftward to AD’. If there is no change in aggregate supply, the economy will reach a new equilibrium at point ‘C’. This will lead to a decline in output from Q to Q’. In addition, prices also decline from P to P’, and the rate of inflation falls.

A Decline in Aggregate Demand Leads to an Economic Downturn

Business Cycle Theories (contd.)

Shifts in Aggregate Demand: Business cycle fluctuation in output, employment, and prices are often caused by ‘shifts in aggregate demand.’ These occur as consumers, businesses, or governments change total spending relative to the economy’s productive capacity. When these shifts in aggregate demand lead to sharp business downturns, the economy suffers recessions or even depressions. A sharp upturn in economic activity can lead to inflation.

This theory was propounded by J.M. Keynes.

Business Cycle Theories (contd.)

Monetary Theory: The monetary theories attribute business fluctuations to the ‘expansion and contraction of money and credit (Milton Friedman). Under this approach, monetary factors are the primary source of fluctuationes in aggregate demand.

For example, the recession of 1981-82 in the US was triggered when the Federal Reserve raised nominal interest rates to 18 percent to fight inflation.

The Multiplier-Accelerator Model proposes that exogenous shocks are propagated by the multiplier mechanism along with a theory of investment called accelerator principle (P. Samuelson). This theory shows how the interaction of multiplier and accelerator can lead to regular cycles in aggregate demand; it is one of the few models that generates internal cycles.

Business Cycle Theories (contd.)

Political theories of business cycles attribute fluctuations to politicians who manipulate economic policies in order to get reelected (W. Nordhaus, E. Tufte).

Historically, presidential elections in the United States are sensitive to economic conditions in the year preceding the election.

For example, the American economy went through a deep recession early in his first term but by the time he was running for reelection in 1984, the economy wa growing rapidly, which contributed to a reelection landslide.

Business Cycle Theories (contd.)

Equilibrium-business-cycle theories claim that misperceptions about price and wage movements lead people to ‘supply too much or too little labour,’ which leads to fluctuations of output and employment (R. Lucas, R. Barro, T. Sargent).

In one version of these theories, unemployment rises in recessions because workers are holding out for wages that are too high.

Real-business-cycle proponents hold that innovations or productivity shocks in one sector can spread to the rest of the economy and cause recessions and booms (J. Schumpeter in the 20th century and E. Prescott, P. Long, C. Closser in recent years). In this classical approach, cycles are caused primarily by ‘shocks to aggregate supply,’ and not by changes in aggregate demand.

For example, such an approach looks particularly attractive for explaining situations in Russia, which made a transition from central planning to the market economy in the 1990s.

Business Cycle Theories (contd.)

Supply shocks occur when business fluctuations are caused by shifts in aggregate supply (R. J. Gordon).

The classic examples came during the oil crises of the 1970s, when sharp increases in oil prices contracted aggregate supply, increased inflation, and lowered output and employment.

Many economists think the low inflation and rapid growth of the American in the 1994-1999 period may be explained by favourable supply shocks. During this period, costs grew slowly because of declining oil and commodity prices, declining import prices, rapid productivity growth, and below-par increase sin medical-care prices.

Forecasting Business CyclesEconomists have developed forecasting tools to help them foresee

changes in the economy: Econometric Modeling and Forecasting: For a detailed look into the

future, economists turn to computerized econometric forecasting models. An ‘econometric model’ is a set of equations, representing the behavior

of the economy, that has been estimated using historical data. Generally, modelers start with an analytical framework containing

equations representing both ‘aggregate demand’ and ‘aggregate supply’. Using the techniques of modern econometrics, each equation is “fitted”

to the historical data to obtain “parameter estimates” (such as MPC, the slope of the investment demand function, etc.).

In addition, modelers use their own experience and judgement to access whether the results are reasonable.

Under ordinary circumstances, the forecasts do a fairly good job but at other times it is a hazardous profession. Figure 23-5 shows the results of a recent survey, using a benchmark (naive forecast) for comparison purposes.

Professional Forecasts

Foundations of Aggregate DemandAggregate demand (or AD) is the total or aggregate quantity

of output that is willingly bought at a given level of prices, other things held constant.

AD is desired spending in all product sectors: consumption, private domestic investment, government purchases of goods and services, and net exports.

Aggregate demand has four components: 1. Consumption (C): Consumption is primarily determined by

disposable income, which is personal income less taxes. Other factors affecting consumption are longer-term trends in income, household wealth, and the aggregate price level.

Aggregate demand analysis focuses on the determinants of “real consumption” (that is, nominal or dollar consumption divided by the price index for consumption).

Foundations of Aggregate Demand (contd.)Investment (I): Investment spending includes

purchases of buildings, software, and equipment and accumulation of inventories.

Major determinants if investment are the level of output, the cost of capital (as determined by tax policies along with interest rates and other financial conditions), and expectations about the future.

The major channel by which economic policy can affect investment is monetary policy.

Foundations of Aggregate Demand (contd.)Government Purchases (G): This component

of aggregate demand includes government purchases of goods and services like military equipment or road building equipment as well as the services of judges, public school teachers, and other government employees.

Unlike private consumption and investment, this component of aggregate demand is determined directly by the government’s spending decisions.

Foundations of Aggregate Demand (contd.)Net Exports (X): The final component of aggregate demand is

‘net exports,’ which equal the value of exports minus the value of imports.

Imports are determined by domestic income and output, by the ratio of domestic to foreign prices, and by the foreign exchange rate of the respective currency.

Exports are the mirror image of imports, determined by foreign incomes and output, by relative prices, and by foreign exchange rates.

Net exports, then, will be determined by domestic and foreign incomes, relative prices, and exchange rates.

Figure 23-6 shows the AD curve and its four components. At price level ‘P’, we can read the levels of consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports, which sum to GDP, or Q.

The sum of four spending streams at this price level is aggregate spending, or aggregate demand, at that price level.

Components of Aggregate Demand

The Downward Sloping Aggregate Demand Curve

The aggregate demand curve slopes downward primarily because of the “money-supply effect”.

When we draw an AD curve, we hold other things constant. One important variable that is held constant in “nominal money supply” (i.e. the dollar/Re. value of the money supply).

So when prices rise, the “real money supply” (defined as the nominal money supply divided by the price level) must fall. For example, suppose the nation’s money supply is constant at $ 600 billion. Then, if the consumer price index doubles, the real money supply falls from $ 600 billion to $ 300 billion.

As the real money supply contracts, money becomes scarce or “tight.” Interest rates and mortgage payments rise, and credit becomes harder to obtain; tight money causes a decline in investment and consumption.

In short, a rise in prices with a fixed money supply, holding other things constant, leads to tight money and produces a decline in total real spending. The net effect is a movement up and to the left along the sloping AD curve.

The Downward Sloping Aggregate Demand Curve (contd.)

“The m0ney-supply effect” is illustrated in Figure 23-7(a). The economy is at an equilibrium at point B, with a price level

of 100 (at constant prices), a real GDP of $3000 billion, and a money supply of $ 600 billion.

Assume that the price inflation increases by 50 percent, so the price index increases from 100 to 150.

With a fixed nominal money supply, the real money supply declines from $600 billion to $300 billion.

Tight money raises interest rates and lowers spending in interest sensitive sectors like housing, plant and equipment, and automobiles.

The net effect is that total real spending declines to $2000 billion, shown a point C.

The decline in the real money supply will affect aggregate demand through the important money mechanism.

Movement along Vs. Shifts of Aggregate Demand

Shifts in Aggregate DemandThe determinants of aggregate demand can be separated into to

categories:i. Macroeconomic Policy Variables: These are policy variables

under government control, which include ‘monetary policy’ and ‘fiscal policy’.

ii. Exogenous Variables: The second category is ‘exogenous variables’ or variables that are determined outside the AS-AD framework.

As shown in Table 23-1, some of these variables (such as wars and revolutions) are outside the scope the of macroeconomic analysis proper; some (such as foreign economic activity) are outside the control of domestic policy, and others (such as the stock market) have significant independent movement.

As shown in Figure 23-7 (b), other things being no longer constant, changes in variables underlying AD (such as money supply, tax policy, or military spending) lead to changes in total spending at a given price level. This leads to a “shift” of the AD curve.

Factors Leading to a Shift in Aggregate Demand