Bushidō in Transformation: Japanese Warrior Culture and ... · Bushidō in Transformation:...

Transcript of Bushidō in Transformation: Japanese Warrior Culture and ... · Bushidō in Transformation:...

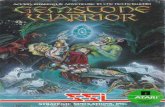

Bushidō in Transformation: Japanese Warrior Culture and

Martiality

PROGRAMME AND BOOK OF ABSTRACTS

International Symposium of the Department of Asian StudiesAugust 25-26, 2017

Bushidō in Transformation: Japanese Warrior Culture and

Martiality

PROGRAMME AND BOOK OF ABSTRACTS

International Symposium of the Department of Asian StudiesAugust 25-26, 2017

Venue: National Museum of Slovenia, Maistrova Street 1, Ljubljana

Bushidō in Transformation: Japanese Warrior Culture and MartialityProgramme and Book of Abstracts

Organising committee: Nataša VISOČNIK (University of Ljubljana) Tinka DELAKORDA KAWASHIMA (Yamaguchi Prefectural University) Klara HRVATIN (University of Ljubljana)Luka CULIBERG (University of Ljubljana)

Editor: Nataša VisočnikLayout: Jure PreglauCover photography: Sora, Adobe Stock

© University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Arts, 2017.All rights reserved.

Published and issued by: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani (Lju-bljana University Press, Faculty of Arts)Issued by: Department of Asian Studies and Centre for Japanese StudiesFor the publisher: Branka Kalenić Ramšak, Dean of the Faculty of Arts

Ljubljana, 2017First Edition.Number of copies printed: 60Publication is free of charge.

Supported byDepartment of Asian Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of LjubljanaCentre for Japanese Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of LjubljanaNational Museum of SloveniaEmbassy of Japan in Slovenia

Endorsed byKashima-Shinryu Federation of Martial Sciences

CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji

355.01(520)(082)

INTERNATIONAL Symposium of the Department of Asian Studies (2017 ; Ljubljana) Bushido in transformation : Japanese warrior culture and martiality : programme and book of abstracts / International Symposium of the Department of Asian Studies, August 25-26, 2017, National Museum, Ljubljana ; [editor Nataša Visočnik]. - 1st ed. - Ljubljana : Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete = Univer-sity Press, Faculty of Arts, 2017

ISBN 978-961-237-948-3 1. Visočnik, Nataša 291322624

286155520

5

Welcome AddressWe would like to express a warm welcome to all participants of the Internation-al Symposium of the Department of Asian Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, in cooperation with the Centre for Japanese Studies on “Bushidō in Transformation: Japanese Warrior Culture and Martiality.” It is a great honour to have so many scholars from different countries and research fields contribute their research results to this broad topic. Thus, we are convinced this symposium will be successful in forming some new interdisciplinary ap-proaches, as well as in establishing new professional academic connections and friendships.

This international symposium is part of a larger project of the Department of Asian Studies, called Japan in Our Midst (JAPOM), accompanying the exhibi-tion Paths of the Samurai, Japanese Arms and Martial Culture in Slovenia of the National Museum of Slovenia. The project takes place from May to October this year and connects different academic and educational institutions. Jointly, we have organised a number of activities throughout Slovenia to bring various aspects of Japanese culture closer to the wider Slovenian public. Being part of this larger project, our symposium aims to create an opportunity for a meeting and discussion between expert researchers from various fields on historical is-sues that bear a high significance also for this day and age. Bushidō, “the way of the warrior”, also known as the “the soul of Japan”, is said to be one of the most essential elements of Japanese culture, but rich in various stereotypes and distorted images that the general public holds about Japan and through which it understands contemporary Japanese society.

This international symposium aims to bring fresh perspectives on the role and relevance of the traditional Japanese ideology of bushidō in the contemporary world. The concept of bushidō will be critically presented and thoroughly ex-amined by renowned Slovenian and international symposium participants from the fields of Japanese history, archaeology, religion, sociology, anthropol-ogy, arts, etc. They will unveil their views on the ideology of bushidō, the war-riors’ way of life, religious traditions in bushidō, the transformation of bushidō through centuries, spreading from Japan to the world, the invention of tradi-tion and the impact of bushidō on different segments of the contemporary Japanese society. We will also discuss the influence of bushidō in contemporary martial arts, the development of martial arts in Japan and their expansion worldwide.

6

In the end, we would also like to thank everyone for all the support from the Faculty of Arts, National Museum of Slovenia, the Embassy of Japan in Slove-nia, Kashima-Shinryu Federation of Martial Sciences to other institutions and individuals that made this symposium possible. Special gratitude goes to our colleague and member of Kashima-Shinryu, dr. Tinka Delakorda Kawashima, for her help in establishing the necessary connections and communication with distinguished lecturers in the symposium. We wish the participants a lively and highly stimulating exchange of opinions during the next two days of debate, both on and off the floor.

Nataša VisočnikTinka Delakorda Kawashima

Organising Committee

7

Programme of Symposium

FRIDAY, 25th August

TIME SUBJECT

8:00-9:00 Registration

9.00-9.45 Welcome Addresses: Nataša VISOČNIK, Assist. Professor, University of Ljubljana,Barbara RAVNIK, M.A., Director of National Museum of SloveniaAndrej BEKEŠ, Professor Emeritus, Guest of Honour: His Excellency FUKUDA Keiji, Embassy of Japan in Slovenia

9:45-10:15 Guest of Honour: SEKI Humitake, Professor Emeritus (University of Tsukuba, Japan): Authentic Etymology of Japanese Chivalry “Bushidō” and Its Martiality

10:15-11:00 Keynote Lecture 1: William BODIFORD (University of California, Los Angeles, USA): Lives and Afterlives of Bushidō: A Perspective from Overseas

11:00-11:15 Coffee Break

11:15-12:30 SECTION 1: Bushidō Tradition (Chair: AKINAGA Hiroyuki)

G. Björn CHRISTIANSON (UCL, Consultants Ltd, United King-dom), Mikko VILENIUS (Instructor, Martial Training Bureau of the Kashima-Shinryu Federation of Martial Sciences, UK) and SEKI Humitake (University of Tsukuba, Japan): Role of the Sword “Fut-sunomitama-no-tsurugi” in the Origin of the Japanese Bushidō Tradition

AKINAGA Hiroyuki (National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) and SEKI Humitake (University of Tsukuba, Japan): Phenomenology of Genuine Martiality in Bushidō – Physical Description of the Embodied Cognition

KAWASHIMA Takamune (Yamaguchi University, Japan): Pre- and Proto-Historic Background of Martial Arts in Eastern Japan

8

TIME SUBJECT

12:30-14:00 Lunch Break

14:00-16:00 SECTION 2: Martial Arts in Practice – Measuring and Transmit-ting (Chair: Tinka DELAKORDA KAWASHIMA)

Jernej SEVER (Premik Centre, Ljubljana, Slovenia): Researching and Measuring Basic Principles of Chinese and Japanese Martial Arts

Jari Matti RENKO (Oy Apotti Ab, Finland): Takemikazuchi-no-Mikoto and Väinämöinen: A Case Example of Utilizing Pre-Christian Fenno-Ugric Myth Pattern as a Cultural Bridge in Transmission of Koryū Bugei

Nataša VISOČNIK (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia): Samurai in Slovenia: Cultural Influences and Transmission of the Japanese Martial Arts to Slovenia

Ari YLINIEMELÄ (Tamro Oyj, Finland): Kashima-Shinryū Instruction in Finland: The Challenges and the Rewards

Ryan JEPSON (University of Vienna, Austria): Aikido: A Report on Ki No Kenkyukai (Ki-Aikido) Developments in Europe

16:15-17:30 SECTION 3: Bushidō’s Influence in Modern and Contemporary Japan and Europe (Chair: Andrej BEKEŠ)

M. Teresa RODRÍGUEZ-NAVARRO (University of Granada, Spain): The Reception of Bushidō. The Soul of Japan by Nitobe in Mod-ern and Contemporary Spain

Andrew HORVAT (Josai International University, Japan): Bushidō Seen and Unseen: the Lasting Influence of Samurai-inspired Moral Values in Modern Japan

Mikko VILENIUS (Instructor, Martial Training Bureau of the Kashima-Shinryu Federation of Martial Sciences, UK): Traditional Warrior Education in Modern Organisational Context: A Case Study of the Kashima-Shinryu Federation of Martial Sciences

19.00 Dinner

9

SATURDAY, 26th August

TIME SUBJECT

8:00-9:00 Registration

9:00-10:00 Keynote Lecture 2: Karl FRIDAY (Saitama University, Japan): Way of What Warriors? Bushidō & the Samurai in Historical Perspective

10:00-11:40 SECTION 4: Invented Histories - Meiji (Chair: Nataša VISOČNIK)

Luka CULIBERG (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia): Discipline and Punishment: Honourable Death as Mechanism of Political Control

Nathan LEDBETTER (Princeton University, USA): Invented His-tories: The Nihon Senshi of the Meiji Imperial Japanese Army

Simona LUKMINAITĖ (Osaka University, Japan): Bushidō in the Meiji Education of Women

Danny ORBACH (Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel): “A Mys-terious Ideal”: Bushidō and the Leniency to Right-wing Terror-ists in Prewar Japan

11:40-14:00 Martial Arts Day at the National Museum & Lunch Break

14:00-15:15 SECTION 5: Samurai Ideal: History, Religion (Chair: Klara HR-VATIN)

Aldo TOLLINI (Ca’ Foscari University Venice, Italy): The Formation of the Ideal of the Samurai. From Kakun to Bushidō

Tinka DELAKORDA KAWASHIMA (Yamaguchi Prefectural Univer-sity, Japan): Kirishitan Samurai and the Christian Heritage in Nagasaki

Claudia MARRA (Nagasaki University of Foreign Studies, Japan): Bureiuchi – Facts and Fiction

15:15-15:30 Coffee Break

10

TIME SUBJECT

15:30-16:15 SECTION 6: Bushidō and Arts (Chair: Luka CULIBERG)

Klara HRVATIN (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia): The Creation of Modern Fighting Force and the Arrival of Western Music in Japan – Bakumatsu Marching Bands

Naama EISENSTEIN (SOAS, University of London, United King-dom): The Art of Deception: Trickery on the Battlefield and Its Representation in Early Modern Japanese Art

16:15-16:45 Closing Remarks (Asian Studies Journal, Special Issue, Guest Edi-tors)

17:00-18:00 Practical/Interactive Demonstration of Kashima-Shinryu Mar-tial Arts School

18:30 Dinner

POSTER PRESENTATIONS

Jérémie BRIDE (University of Tsukuba, Japan): Intercultural Genealogy of Karate Practices from a Cultural Perspective

Mateja ŽABJEK (University of Tsukuba, Japan): Making of Sacred Sites in Japanese Martial Arts: Case Study of Mt. Mitsumine and Kyokushin Karate

13

GUEST OF HONOUR

Authentic Etymology of Japanese Chivalry “Bushido–” and Its MartialitySEKI Humitake

The authentic etymology of Japanese chivalry “bushidō” and its martiality’ are shown and discussed, mainly based on the three most important historical records of the mythological age of Japan, i.e., Kojiki (古事記), Nihonshoki (日本書紀), and Sendaikujihonki (先代旧事本紀), summarized as follows:

From the time of its creation by the 1st generation deity “Ame-no-Minakanushi-no-Mikoto (天之御中主尊)” until the present day, the universe has continuous-ly evolved. Because the “divine intent (shin’i 神意)” that guides this evolution and the “divine dynamics” that propel it have placed humankind in control of this biosphere, the greatest Martial Might of Heaven, the deity Takemikazuchi-no-Mikoto (武甕槌尊), acting in his role as a divinity for the practical applica-tion of creative energies (musubi 産) revealed the divine martiality (shinbu 神武) to human beings. This divine martiality of “Takemikazuchi-no-Mikoto” has been transmitted as the real “Martiality of Bushidō” amongst academic researchers and scholars in Shintoism from generation to generation.

14

KEYNOTE LECTURE 1

Lives and Afterlives of Bushido: A Perspective from OverseasWilliam BODIFORD

Bushido is an elusive concept. Since the early twentieth century, when it first became a topic of public discourse among social critics, journalists, politi-cians, religious leaders, historians, and the general public, bushido has been praised, blamed, and debated in a bewilderingly wide array of contexts: Chris-tian thought, Buddhist thought, Shinto ideology, cultural identity, nationalist discourse, military policy, warrior ethos, physical and psychological training, group socialization, war crimes, sports, economic organization, invention of tradition, and so forth. A brief survey of just a few of these contexts reveals that bushido has had many different lives. The many legacies of these persist as a se-ries of afterlives that, in a surprising number of cases, have followed rather dif-ferent trajectories within Japan and overseas, even if they are never completely unrelated. These transformations and afterlives constitute valuable witnesses that offer competing narratives of Japan’s modern development and of the country’s changing roles in the world. Beyond Japan they speak to the multiple ways that the nation both inspires and (sometimes) displeases the world. These lives and afterlives also contribute to a larger story. Bushido serves to illustrate the myriad ways that intersections of the local and translocal, the past and present, refract perspectives. Bushido is not unique in its ability to assume di-vergent connotations and implications in accordance with the contours of the contexts within which it is placed. Its elusiveness exemplifies the amorphous characteristics of our global world’s nomadic lexicon, not just in the humani-ties, but also in sciences and social sciences. From this perspective bushido raises useful questions about how we study and translate Japan.

15

KEYNOTE LECTURE 2

Way of What Warriors? Bushido– & the Samurai in Historical PerspectiveKarl FRIDAY

The role of the samurai in modern Japan is analogous to that of the cow-boy in contemporary America: He is at once an entertaining, romantic figure and a fundamental representative, a symbol, of the national character. The influence of these warriors and the tradition they represented remain vigorous and widespread today, as can be seen in the ever-increasing popularity of such martial arts and sports as kendō, and in the pervasiveness of samurai images in films, television, and advertising. And yet the majority of what samurai afi-cionados—and a great many scholars of Japan as well—believe about samurai culture derives from a consciously-fashioned mythology that bear scant resem-blance to historical reality. Indeed, to describe samurai culture in historical reality, we must first ask “which samurai historical reality?” For warrior values and behaviour changed many times during the nearly millennium-long epoch between their first appearance and the abolition of the samurai class in the 1870s. This lecture will examine the evolution of the warrior ethos in Japan, with special attention to the key constructs of honour and loyalty.

16

SECTION 1: BUSHIDO– TRADITION

Role of the Sword “Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi ” in the Origin of the Japanese Bushido– Tradition

G. Björn CHRISTIANSON Mikko VILENIUSSEKI Humitake

One of the formative narratives in Japanese martial arts is the bestowal of the mystical sword “Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi (布都御魂釼)” upon Emperor Jinmu, the legendary founder of Japan. Within the Kashima Shinden Bujutsu (鹿島神傳武術) lineage, this bestowal is attested as a critical event in the ini-tiation of the principles of bushidō martiality. However, the practical reasons for its significance has been unclear. Drawing on historical and archaeologi-cal records, in this paper we hypothesise that the physical conformation of the legendary sword Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi represented a comparatively incremental progression from the one-handed short swords imported from mainland Asia. These modifications, however, allowed for a new, two-handed style of swordsmanship, and therefore it was the combination of the physical conformation of Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi and the development of appropri-ate techniques for wielding it that formed the basis of the martial significance of the “Law of Futsu-no-mitama (韴霊之法則)”. Drawing on various traditions and records linking Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi to the Kashima Grand Shrine (鹿島神宮), we also argue that this new tradition of swordsmanship was the nucleus around which the Kashima Shinden Bujutsu lineage would develop, and therefore represented a critical first step towards the later concepts of bushidō. Based on the kabala of the Kashima Shinryū, we also present a work-ing model of what the techniques for usage of Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi might have been, and provide an account of an experiment testing its application.

17

Phenomenology of Genuine Martiality in Bushido– – Physical Description of the Embodied Cognition

AKINAGA Hiroyuki SEKI Humitake

“Genuine martiality (真武)” is the physical appearance of “divine martiality (神武).” To personify the genuine martiality is indispensable to understand-ing bushidō. We first show the physical description of the genuine martiality. The “Fivefold Laws,” the Laws governing the ultimate principle of the divine school, are introduced (Seki 1976, 19–23). By making an alignment between the “Fivefold Laws” and the “Eight Divine Coordinators,” one can realize the physical vectors of the martial art movement, which should be the physical representation of the “Genuine martiality” through embodied cognition. Next, the perceptual process of cognition is described by using physical analogies, such as a quantum mechanical behaviour and critical phenomena (Ryu et al. 2007, 574). Cognition is the intrinsic process for “bushidō-minded person (志士)” to refine the motive force, which cannot be replaced by artificial intel-ligence, even after any proposed Singularity.

References:Seki, Humitake. 1976. Nihon-budō no engen: Kashima-Shinryū. Tokyo: Kyorin

shoin. Ryu, Kwang-Su, Hiro Akinaga and Sung-Chul Shin. 2007. Nature Physics 3.

18

Pre- and Proto-Historic Background of Martial Arts in Eastern JapanKAWASHIMA Takamune

Kashima City is best known as a birthplace of martial arts in Japan. While Kashima Shinryū was officially established in the latter half of the medieval pe-riod, there was a long tradition of martial arts in the Kashima region since the Kofun period (AD250-700). This paper focuses on archaeological remains and landscape around the Kashima Great Shrine, to clarify the significance and influence of the Shrine in managing the eastern part of the territory of ancient Japan. I will examine some characteristics of the region, such as its coastal location that enabled the transportation of materials and soldiers. Another key characteristic of the place could be the metal production represented by the legendary giant sword. Ancient workshops for metallurgy were found at the former local government office in Hitachi-no-kuni, the area of today’s Kashima Prefecture. It thus seems no coincidence that Kashima was chosen as a kind of military base. The archaeological facts thus provide a number of reasons why the lineage of various martial arts and schools, including Kashima Shinryū, can be traced to Kashima, which led to the formation of Tōgoku Bushidan in eastern Japan during the medieval period.

19

SECTION 2: MARTIAL ARTS IN PRACTICE – MEASURING AND TRANSMITTING

Researching and Measuring the Basic Principles of Chinese and Japanese Martial ArtsJernej SEVER

If we want to analyse the complex experiences that can be the consequence of martial arts training, we must understand those experiences as a combination of physical and mental processes. This opens up a very important question: How is it possible to research and measure these complex experiences? To solve this problem, we used a cognitive science model which highlights the impor-tance of understanding cognition in connection with the body and its position in a given environment (Clark 1997). In this way, cognitive science helps to bridge the gap between body, brain and environment. This model allows at least two different methodological approaches: a phenomenological analysis of experience and the possibility of quantitative research into specific parts of these experiences.

In our work, we concentrated on the efficiency of martial arts movements. To design proper experiments, we had to understand some of the basic principles of efficiency in martial arts at the level of the first person, and thus used a phe-nomenological approach (Sokolowski 2008). The method we used to describe a complex experience in martial arts is similar to the descriptive experience sam-pling method, which was introduced by Hurlburt and Heavey (2006). In this, the participant must, at random intervals, freeze their current experience and write down a brief description of it in a notebook. In our first person martial arts research, we froze the experience based on the perception of the moment of muscle tension or stiffness of the body that happens in the process of inter-action between fighting partners.

Based on this first-person analysis, we designed three studies. We measured stability (a) (Sever 2013) after a sudden release of horizontal force. We designed a special massage method (b) where we use a slight vibration and three-dimen-

20

sional movement of the joints to achieve better efficiency in a very short time (Sever 2014), and we measured muscle response (c) in the moment of contact of two fighting partners.

Based on our research and experience of the basic principles of martial arts, we have concluded that we need to change our inherited motor responses to achieve more efficient movement and mastery in these arts.

References:Clark, Andy. 1998. Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again. Cam-

bridge, USA: The MIT Press.Hurlburt, Russel. T., and Christopher. L. Heavey. 2006. Exploring Inner Experience.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.Sever, Jernej. 2014. “Modulation of Motor Processes on the Basis of Taijiquan Move-

ment Principles, Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems.” INDECS 12 (4), October.

Sever, Jernej, and Nejc Šarabon. 2013. “Vpliv nenadne razbremenitve sile v vodoravni smeri na stabilnost pri Taijiquanu.” Revija Šport 3-4: 105-110.

Sokolowski, Robert. 2008. Introduction to Phenomenology. London: Cambridge Uni-versity Press.

21

Takemikazuchi-no-Mikoto and Väinämöinen: A Case Example of Utilizing Pre-Christian Fenno-Ugric Myth Patterns as a Cultural Bridge in Transmission of Koryu– BugeiJari Matti RENKO

Many classical Japanese systems of martial arts (koryū bugei) provide a mul-ti-layered system for preserving and transmitting a complex and tightly inte-grated methodology consisting of physical movement, timing, generation and application of power, tactics, strategy and philosophy relevant to combative engagement. These methodologies, that at their highest level are often desig-nated as a form of “spiritual transmission,” utilize as a part of their curricula a rich panoply of esoterica and theory influenced by Buddhist and Shinto lore.

Kashima-Shinryū, tracing its roots back around the periods of Emperor Kenzō (485-487) and Emperor Ninken (488-498) and having taken shape as the for-mal lineage of “bushidō Martiality” during the latter half of the sixteenth cen-tury, is here discussed as case example of such a system.

In modern times, as in the past, if a student initiated into a tradition is not already intimately familiar with the cultural lore in the original pre-modern context, then there is a risk of incorrect transmission if no supplementary methodology of teaching and contextualizing the traditional lore is used. In order to fully transmit the tradition a variety of supplementary methodology is thus used, in concert with the traditional methodology and lore, to ensure both full transmission and intuitive understanding of the meaning and implications of the tradition.

22

Samurai in Slovenia: Cultural Influences and Transmission of the Japanese Martial Arts to SloveniaNataša VISOČNIK

Japanese martial arts have found the way into Slovenia through various roads within different periods. When examining the reasons and causes of the popu-larity of the many schools and clubs in Slovenia, we are learning how these martial arts are taught in these organizations. The research mainly focuses on the study of transmission of Japanese martial arts to Slovene students. The paper thus presents the ways of transmission used with these bodily practices, teaching and learning, in-body learning and the instructional method of the master in relation to the students. From the perspectives of both philosophical anthropology and the humanistic theory of martial arts (Cynarski and Lee-Barron), this paper discusses the possible value and relevance of the traditional warrior pathways of Japanese martial arts to contemporary Western society. Slovene masters and students both explain their understanding of the bod-ily movements, kata, and philosophical and social backgrounds of some of the martial arts. We are also interested in the experiences of the practitioners with regard to gaining knowledge of martial arts and how invested they are in a given moment. The analysis carried out in this work also reveals the major structural constituents that are associated with the pedagogies of certain mar-tial arts. It examines if certain martial arts have demonstrated the value of a discipline in the process of self-discovery; if they can provide a cultural model for learning that is shaped by an interest in peaceful relations; and if the can also provide a pedagogical model that is shaped by themes of blending, integra-tion, wholeness, and unity.

23

Kashima-Shinryu– Instruction in Finland: The Challenges and RewardsAri YLINIEMELÄ

Instructing a traditional Japanese martial art can be a challenge. Provided the instructor is well versed in the schools’ curriculum, the transmission of its tech-niques should be pretty straightforward. However, in the case of old schools, like Kashima-Shinryū, we are not talking only about the kata: we are talking about hundreds of years of accumulated martial lore, culture and history.

Kashima-Shinryū instruction is based on one-to-one, heart-to-heart transmis-sion. It cannot be done effectively using the methods of mass instruction. While finding suitable training facilities is easy, creating an optimal learning environment can be quite demanding. In the absence of the schools’ head-masters’ constant instruction and monitoring, and in the absence of taryū jiai, the next best option is to make the learning and testing environment as realistic possible.

Careful selection of students, especially when establishing a new Kashima-Shinryū branch, is the key to avoiding the big-fish-in-a-small-pond syndrome. A heterogeneous group with a variety of high level skills in other martial arts, mixed with newcomers who have no budō experience whatsoever, is a good starting point. Nothing challenges you more than applying your skills to stu-dents who are adept in their former art, all the while making sure that you lead them towards the correct way of performing Kashima-Shinryū.

The goal of each workout should be training your students, one step at a time, towards mastery of the art. The long-term target is growing a new generation of Kashima-Shinryū experts and instructors who are able and willing to carry the torch. There is nothing more rewarding than witnessing your own students passing the test for menkyo kaiden.

24

Aikido: A Report on Ki No Kenkyukai (Ki-Aikido) Developments in EuropeRyan JEPSON

In the English language Aikido is commonly known as a “martial art”, a trans-lation of “budō” which refers to the code of ethics and set of practices, includ-ing multiple artistic pursuits, that were the “way of the samurai” in feudal Japan, and which remained in existence until the late nineteenth century. This presentation, however, will reflect on the development of Aikido in more re-cent decades and its evolution (as practiced by one organisation in particular) to a way of modern living both as a philosophy, but most importantly, through embodied “somatic” learning and training of mind and body, and, crucially, in a cooperative and non-competitive group environment.

With an emphasis on remedying the inherent and pervasive dualism underpin-ning conflict, violence and its resolution, and traced through a discussion of bushidō in contemporary everyday life, Aikido appears as a practice of “non-fighting” on the one hand and “way of leading one’s life” on the other, which is obtained through serious study of “bodily techniques” to invoke the notion used by M. Mauss. Following this concept, narrative and anecdotal experiences of long-term Aikido practitioners and dojos, and the author’s own experienc-es with starting a dojo and teaching beginners, is reflected on in combining embodied knowledge, practice theory, rhythms and art, and researcher-par-ticipant subjectivities. This theorisation has implications for researching and understanding a broad array of social interactions, practices and situations.

25

SECTION 3: BUSHIDO–’S INFLUENCE IN MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY JAPAN AND EUROPE

The Reception of Bushido–. The Soul of Japan by Nitobe in Modern and Contemporary SpainM. Teresa RODRÍGUEZ-NAVARRO

Until quite recently, Japan was seen as an extremely exotic and distant country in Spain. Consequently, few literary works from Japan were translated into Spanish until the first half of the twentieth century.

This study is part of a wider research focused on the role of paratextual and cultural elements in the construction of the image of Japan in Spain since the twentieth century. Our aim is to discuss on the reception of bushidō in Spain through the translations into Spanish of Nitobe Inazo’s reinterpretation of bushidō in the Meiji Era, pointing out the role of translators and paratexts in the construction/reinterpretation of the values and concepts of bushidō in con-temporary Spain, and its influence in some Spanish Institutions. Moreover, the influence of the context and ideology of translators in the different translations is also analysed here.

In other words, our aim is to present a reflection on the role of translators and publishers in the construction and reception of the image of Japan in Spain, and especially the reception of the values of bushidō. For this task we focus our study on the analysis of paratexts and epitexts of Nitobe´s Bushidō.

In particular book covers, forewords and afterwords from a selection of dia-cronic translations into Spanish will be examined for their influence in the reception community, and also to verify whether the image of Japan reflected in book covers and other paratexts has changed or not in the most recent translations. It is also our goal to stress the importance of translation in the international circulation of an imaginary about East Asia from the Spanish and Catalan research context.

26

Bushido– Seen and Unseen: The Lasting Influence of Samurai-inspired Moral Values in Modern JapanAndrew HORVAT

In Japan, no newspaper has a humour column, and it is rare to see a pun in any headline. Moreover, none publish any letters from readers complaining about articles or editorials. If such an attitude toward journalism seems a bit austere, it is not by accident. The foundations of the country’s modern news media were laid in the 1870s by former samurai, retainers of feudal lords on the losing side of the 1868 civil war that paved the way for the transformation of Japan into a modern nation state. Adherence to samurai-influenced behav-iour in contemporary Japan is hardly anachronistic. Unlike in the West, where reporters can call on “inalienable rights” traceable to the Enlightenment to criticize their governments, in Japan it is by presenting correct moral behav-iour appropriate for a class of leaders that the media is able to act as a check on power. This paper argues that although bushidō in name has been discred-ited, evidence of Confucian-influenced samurai morality can still be found in many aspects of Japanese life. At the university where I teach, students are en-couraged to follow the motto “self-improvement through learning,” an educa-tional philosophy of moral self-strengthening once propagated in books titled Bushidō by both the liberal Nitobe Inazo and the conservative Inoue Tetsujiro. While the former has been debunked as “samurai lore for foreign consump-tion” (Chamberlain, Ota) and the latter’s glorification of selfless loyalty by the 47 rōnin was exposed as anachronistic even in its own day (Bito, Smith), the educational philosophy of character building through learning (Brown) has had a lasting impact, both prior to World War II and since. Though bushidō is no longer invoked to encourage young men to sacrifice themselves to a divine Emperor, samurai-style self-improvement is still called on to inspire students to learn English in order to become better “global human resources.”

27

Traditional Warrior Education in a Modern Organisational Context: A Case Study of the Kashima-Shinryû Federation of Martial SciencesMikko VILENIUS

Traditional Japanese martial arts schools are generally perceived by the public either as strictly hierarchical, inflexible and almost militaristic in their organi-sation and teaching methods, or as “cult-like” secret societies with strict hier-archy and loyalty, working like pyramid schemes in their operation. This first view has been discussed in the literature and among experienced practitioners, and the consensus is that this is mostly a misconception coming from shallow familiarity with some modern East-Asian martial arts. The second view seems to spring from the esoteric nature and traditional religious vocabulary used in the teaching of the schools’ lore and application, both physical and psychological.

In this paper, we use Kashima-Shinryū (KSSR) and its modern administrative organisation into the KSSR Federation of Martial Sciences as a case study for the adaptation of a traditional bugei school into the modern world. We will consider the school from three perspectives: how it facilitates transmission of traditional martial culture in a modern-day context; how its teaching methods operate from the perspective of a student; and how its teaching methods oper-ate from the perspective of an instructor.

Through this, we will show how as a modern organisation the KSSR Federa-tion of Martial Sciences strives to uphold the ideal of the past-day warrior class as contributing members of society––as expressed by the school’s traditional written and oral lore––in its modern-day practitioners. Furthermore, we will consider how this impacts the relation between the KSSR Federation of Martial Sciences and modern society. We will also examine how the kata––a teaching method in the heart of all traditional bugei––develops both the proficiency of the practitioners and the organisation as whole.

28

SECTION 4: INVENTED HISTORIES - MEIJI

Discipline and Punishment: Honourable Death as a Mechanism of Political ControlLuka CULIBERG

In 1702 an incident, generally known as the “Akō vendetta” or the Revenge of the 47 Rōnin, occurred in shogunal capital of Edo. In the aftermath of this event, the rōnin who murdered a bakufu official, blaming him for their lord’s fate, waited for the bakufu authorities to deliver their verdict. After weeks of discussion and deliberation, a sort of compromise punishment had been de-cided upon: the samurai were ordered to commit seppuku. They were punished for violating the government laws, but were given credit as loyal and right-eous retainers (chūshin gishi), one of the main ideological requirements for the Tokugawa period samurai class.

Within the political context of the tenuous balance of power between the sover-eignty of the Tokugawa regime and the local power of feudal lords, the role of the samurai class was slowly being remodelled along the lines of the discourse on bushidō, and one of its key components was the act of “honourable death” by committing ritual of disembowelment, also known as seppuku. I would like to explore the nature of seppuku within the Tokugawa penal and moral institu-tions, and argue that this paragon of bushidō honour was appropriated by the governing regime as a supplementary institution to the legal and penal appara-tuses, enabling a conciliatory solution between the antagonistic or contending ideological demands of legal submission to the shogunate and loyalty to one’s direct lord.

29

Invented Histories: The Nihon Senshi of the Meiji Imperial Japanese ArmyNathan LEDBETTER

From 1893 to 1924, the historical division of the Imperial Japanese Army Gen-eral Staff produced a thirteen-volume collection of campaign studies entitled Nihon Senshi (Military History of Japan). Each volume covered a battle of one of Japan’s “Three Unifiers” in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centu-ries, and as a whole were influential in shaping both Japanese and Western scholarly narratives of those campaigns. Why were these texts written at this time, and why were these particular battles from a span of fifty-five years cho-sen out of all recorded Japanese history? This paper situates these histories within a larger discourse of Meiji national identity formation. Comparison with the contemporary Japanese intellectual and institutional “invented tradi-tions” that provided a nativist rationale for Japan’s emerging modernity sug-gests that Nihon Senshi was part of the Army’s attempt at creating a “modern” but also “Japanese” institutional history. By tying the new Imperial Japanese Army to examples from Japan’s “warring states” period, the Army staff partici-pated in the same process of inventing history as scholars who created a feudal “medieval” in the Japanese past to fit into Western historiography, and intel-lectuals who discovered a “traditional” spirit called bushidō as a counterpart for English chivalry. Moreover, the interpretations of these campaigns placed a few important daimyō as not only paragons of “Japanese” military prowess, but global leaders in the modernization of military tactics and technology, ahead of even their European contemporaries. The Japanese Army desired to be seen as a “modern” military through its invented “institutional” history; it further used this history as a base for the inculcation of its members with bushidō spirit. The Imperial Japanese Army General Staff was thus an active partici-pant in Meiji-era discourses drawing on foreign models to shape institutions, while also creating continuities with the past to reframe itself as a modern heir to this “Japanese” historical tradition.

30

Bushido– in the Meiji Education of WomenSimona LUKMINAITE·

In recent years, the topic of bushidō in education has been explored by Oleg Benesch, Denis Gainty, and several Japanese historians of physical education in Japan. However, the martial arts and bushidō found in the education for women remains an untreated issue, despite the great attention women and their physical education received in discourses regarding the creation of a healthy nation that took place since the Meiji period (1868-1912).

In 1889, Meiji Jogakkō (明治女学校, 1885-1909) started instructing its stu-dents in martial arts, surprising many at the time. The physical and intellectual (文武) training was carried out by Hoshino Tenchi (星野天知, 1862-1950), a Christian man of letters who later played a major role in establishing a literary magazine, Bungakukai (文学界, 1893-1898). Many girls wished to participate in these classes, and 50 students were selected as the first intake. This program of martial arts education was maintained until the school closed.

The school advocated the benefits such education had on girl students in Jogaku Zasshi (女学雑誌, 1885-1904)––a magazine for women that had strong ties with the school––and, when there was a need to show off to the public the work the school was carrying out, chose fierce naginata duels in charity events.This paper thus examines why a self-proclaimed Japanese Protestant school placed martial arts at the centre of its activities, how bushidō and Christian-ity were seen as complementary, and in what ways bushidō for women was reflected in the curriculum.

31

“A Mysterious Ideal”: Bushido– and Leniency to Right-wing Terrorists in Pre-war JapanDanny ORBACH

In October 1931, a group of Japanese officers were arrested in Tokyo and charged with plotting the assassination of the entire civilian cabinet. During their arrest, the commandant of the military police duly noted that they would be treated “according to the principles of bushidō”. The implications of this lofty statement were rather amusing: they were “detained” for two weeks in a comfortable inn, with alcohol and Geisha on demand. The leniency shown to the military terrorists of the “Cherry Blossom Society” (Sakura-kai), promoted a series of further right-wing coups and assassinations, until the dramatic up-rising of February 26, 1936. The uprisings of the 1930s, as many scholars have noted, had a significant role in the militarization of Japan and its imperial overreach during the second half of that decade.

Why was the legal system in Japan so friendly to right-wing offenders, even when they tried to assassinate leading statesmen and generals? The answer, as I will try to show in this paper, is intertwined with ideological concepts devel-oped since the 1860s, driven by Japan’s peculiar form of modernization, and combined with the emerging ideology of bushidō. However, this was not merely bushidō as the imagined “way of the samurai”, but rather the selective memory of particular groups of rebellious samurai active in the late Tokugawa Period.

32

SECTION 5: SAMURAI IDEAL: HISTORY, RELIGION

The Formation of the Ideal of the Samurai. From Kakun to Bushido–

Aldo TOLLINI

The ideal of the samurai has a long history in Japan, which can be traced back to the Kamakura period and the literature of kakun. Over the centuries it changed significantly, and assumed the connotations of the various cultural environments it existed within. The influence of Zen and Confucianism are most relevant here, and played a crucial role. Inazō Nitobe’s Bushidō must thus be considered as the result of a long itinerary.

My presentation will deal with the transformation of the ideal of the samurai in particular from the Muromachi period, when the influence of Zen was para-mount, to the rise of bushidō, which is characterized by Confucian ideals.

33

Kirishitan Samurai and the Christian Heritage in NagasakiTinka DELAKORDA KAWASHIMA

In research on Christianity in Japan, the missionaries and military nobil-ity, such as daimyō and samurai, used to play a central role; however, since WWII, commoners took over as the main figures of interest. In this paper, I argue that the kirishitan samurai powerfully re-emerged in the public imagi-nation due to the recent heritization of the Christian-related assets for the UNESCO World Heritage Site project in various parts of Japan. I touch upon three main issues, (1) the 16th- and 17th-century persecution of Christianity in Japan; (2) the new insights into martyrdom brought about by the process of heritization; and (3) the latest beatification of samurai martyrs by the Ro-man Catholic Church. I analyse the expressions of the Japanese and foreign Catholics, the Catholic Church, as well as the secular interest groups (for tourism and regional promotion) related to heritization and beatification to discuss how, in these processes, some reasserted aspects of the Japanese “samurai” and “kirishitan” figures can affect and retrigger religious feelings and moral commitments among today’s Catholics.

34

Bureiuchi – Facts and FictionClaudia MARRA

Hardly a samurai movie resists the cliché of the hot-tempered warrior claiming his right to “bureiuchi (無礼討ち)” or “kirisute gomen (切捨御免)”, by chop-ping of the head of a hapless bystander, who had failed to bow deep enough or otherwise shown disrespect.

In this lecture, I would like to shed some light on the facts and rules of “bu-reiuchi” as stipulated in the Kujikata Osadamegaki (公事方御定書), a 1742 collection of rules, governing and reshaping this privilege of the samurai class in the context of the Edo period’s social stratification.

35

SECTION 6: BUSHIDO– AND THE ARTS

The Creation of a Modern Fighting Force and the Arrival of Western Music in Japan – Bakumatsu Marching BandsKlara HRVATIN

Western music now plays an important role in the musical world of Japan. Its strong presence can be found in the school curriculum from the elementary level onward, and it is well embedded in the everyday lives of the Japanese people. Indeed, Japan is one of the most important markets for this kind of music, and is also advancing the craft of making Western musical instruments. But if we want to track the first arrivals of Western music in Japan, we have to consider its role in relation to the creation of a modern fighting force in the late 19th century.

Before the start of the first full-blown military band, under the instruction of Bandmaster John William Fenton in 1869, the first groups to spread Western music were the kotekitai – simple fife and drum bands, which were required as a part of the modern Western military drill formation. One of these was Yamagunitai (1968), an armed force of farmers from the village of Yamaguni in the Tanba Province, which served in the Boshin War (1868-1869). How did this kotekitai music spread to Japanese islands? What kind of notation did they use for disseminating and learning it, for we know that the Japanese approach to notation differs from genre to genre, and functions as an auxiliary means for musical memorization. How did they accept and assimilate music whose rhythm and tone color differed greatly from their own musical culture? An-swers to these questions, and more knowledge about the socio-military struc-ture of the Yamagunitai, could give us a better insight into one of the earliest Japanese integrations of domestic and Western musical elements.

36

The Art of Deception: Trickery on the Battlefield and Its Representation in Early Modern Japanese ArtNaama EISENSTEIN

The honour and reputation of a warrior is his most important possession, and a shameful act will blemish his name for generations. This notion was a vital issue in warrior culture; yet, over the years the understanding of what is a ‘shameful act’ has changed significantly. One example is battlefield conduct, including the use of deception to defeat your enemy, known as “damashi-uchi (だまし討ち)”. In medieval Japan damashi-uchi was considered not only an acceptable tactic, but an admired one. A warrior’s ability to deceive his foe and thus win the battle was proof of his resourcefulness and intellect. To lose in such battle of wit meant inaptness and, in most cases, death. Damashi-uchi was the direct result of battlefield experience in war-worn medieval Japan, but how was it received in the peaceful years of Tokugawa Japan?

I examine this question through artistic representations of damashi-uchi from the Heike monogatari. My main example is the First Across the Uji-River (宇治川先陣) episode. While less dramatic than other examples, such as the Death of Etchū no Zenji (越中前司最期), the story of Sasaki Shirō Takatsuna (佐々木四郎高綱) and Kajiwara Genda Kagesue (梶原源太景季) racing to be first on the battlefield is one of the most frequently depicted Genpei stories in Toku-gawa art. My study examines how the story of this race was used in Tokuwaga times. I will discuss the meaning and function of artworks made for elites and commoners, and what they can teach us about the changes in warrior ideals over time.

37

POSTER PRESENTATIONS

Intercultural Genealogy of Karate Practices from a Cultural PerspectiveJérémie BRIDE

Karate is a martial that is somewhat apart from others in Japan. Indeed, karate was not originally from the main island and has a long history that takes roots in different places in Asia. As such, the genealogy of karate is particularly inter-esting and dynamic, having gone through many intercultural exchanges. Half originally from China (Shaolin, Fuzhou) and half from ancient techniques in Okinawa, karate moved to the main island of Japan only recently (a hundred or so years ago), while its original Sino-Okinawan name also changed, before travelling worldwide, following the trend of globalization. Karate is continuing its internationalization and transformation, and will appear for the first time as an Olympic event at the Tokyo 2020 Games. It is indeed a representative example of a martial art in constant transformation since its ancestral origin.

In this presentation, karate will be presented as a cultural heritage from an an-thropological didactic perspective, showing its transformation in the process of intercultural mediation through generations of masters, evolving from place to place under the cultural influence of actors from each area it has migrated to.

The methodology of the research includes a socio-historical study, an ethno-graphic work with notes taken from the field in France and Japan (t=2.5years in Okinawa, Tsukuba, Osaka), and interviews with karate “Grand Masters” (N=8, four in France, four in Japan).

The results show the interesting migration of karate through time and space, as we can observe with a genealogical map of karate practices. Ethnographic notes reveal the current intercultural mediation of various practices according to the places where they were observed (France or Japan). The transcriptions of the interviews with Grand Masters (N=96,635 words) allow us to gain access to the origin of the transformation of the practices according to the mediation processes operated by its main actors, the Masters.

38

Making of Sacred Sites in Japanese Martial Arts: Case Study of Mt. Mitsumine and Kyokushin KarateMateja ŽABJEK

In this study, I am researching the formation of sacred sites in relation to martial arts in Japan. My case study is Mt. Mitsumine (Mitsuminesan 三峰山), which is a sacred site of the International Karate Organization Kyokushinkai-kan (Kokusai Karatedō Renmei Kyokushinkaikan 国際空手道連盟極真会館; hereafter IKO Kyokushinkaikan). Mountains are a very popular location for martial arts training in Japan. Many martial arts schools thus conduct vari-ous mountain practices each year, in order to toughen the members from the spiritual as well as physical perspective. The origins of mountain training can be found in Shinto mythology and ascetic practices, which most often involve rituals of purification under waterfalls. In my study, however, I try to argue that for the IKO Kyokushinkaikan members the perception of Mt. Mitsumine as a sacred mountain is different from general interpretations of such mountains in Japanese martial arts. In its history of mountain practice that is more than 50 years old, IKO Kyokushinkaikan members have assigned a personal mean-ing and importance to Mt. Mitsumine. I believe that the founder of Kyokushin karate, Ōyama Masutatsu, plays a key role in the perception of Mt. Mitsumine as a sacred mountain.

Ōyama established IKO Kyokushinkaikan in June 1964. He developed a full-contact style of karate, which he named Kyokushin, that is presently one of the most widespread and influential styles in the world. Ōyama passed away in 1994 and was succeeded by Matsui Shōkei as president of the organization, a man who continues the established customs of mountain practices on Mt. Mitsumine, as well as holding memorial ser-vices for Ōyama.

39

BIOGRAPHIESAKINAGA Hiro was born in Tokyo, Japan, on June 27th, 1964. He received his B.E., M.E. and PhD degrees from the University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan, in 1987, 1989 and 1992, respectively. From 1997 to 1998, he was a Visiting Scientist at Imec, Leuven, Belgium. He has been appointed to professorships at the University of Tokyo (2001), Tokyo Institute of Technology (2002-2004), and Osaka University (2008, 2010). Currently, he is a Principal Research Man-ager at the Nanoelectronics Research Institute, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST).E-mail: [email protected]

William M. BODIFORD earned his PhD in Buddhist Studies at Yale University, and did additional graduate training at the University of Tsukuba and Komazawa University. Before moving to UCLA, where he teaches Buddhist Studies and the religion of Japan and East Asia, he taught at Davidson College, the University of Iowa, and Meiji Gakuin University in Tokyo and Yokohama, Japan. His research spans the medieval, early modern, and contemporary periods of Japanese his-tory. Currently he is investigating religion during the Tokugawa period, especially those aspects of Japanese culture associated with manuscripts, printing, secrecy, education, and proselytizing. Although many of his publications focus on Zen Buddhism (especially Soto Zen), he also researches the Tendai and Vinaya Bud-dhist traditions, Shinto, folklore and popular religions, as well as Japanese martial arts and traditional approaches to health and physical culture. A few of his pub-lications include the books Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan (2008) [1993] and Going Forth: Visions of Buddhist Vinaya (2005), The Encyclopedia of Buddhism (2003), which he co-edited, and articles like “Dharma Transmission in Theory and Prac-tice,” “Zen and Japanese Swordsmanship Reconsidered,” and many more.E-mail: [email protected]

Jérémie BRIDE, with a PhD in Sport Sciences, specializing in intercultural me-diation through martial arts and sports (PhD thesis on Japanese/French karate practices), now works on projects for development and peace through martial arts and sports in different countries. He has been practicing karate from age 15, and lived for a total of four years in Japan (Okinawa, Osaka, Tsukuba). He now works at the University of Tsukuba as Assistant Professor for a new pro-gram about Global Issues, and associated researcher at the laboratory ICARE (EA7389; University of La Réunion, France, Indian Ocean) specializing in educa-tion and intercultural studies.E-mail: [email protected]

40

G. Björn CHRISTIANSON holds a PhD in Computation and Neural Systems from the California Institute of Technology. He has been awarded menkyo kaiden with Kashima-Shinryu.E-mail: [email protected]

Luka CULIBERG earned his degree in the sociology of culture and Japanese studies from the University of Ljubljana. He spent several years studying in Japan, at the University of Tsukuba and Hitotsubashi University. In 2015 he earned his PhD from the Sociology Department at the University of Ljubljana, exploring the relationship between language ideologies and social change in modern Japan. He is currently Assistant Professor at the Department of Asian Studies at the same university.E-mail: [email protected]

Andrew HORVAT is professor by invitation at Josai International University, where he teaches courses on journalism, contemporary history and language policy. Horvat’s most recent publication is “Japan’s News Media – How and Why Reporters and News Organizations Influence Official Policy,” in Kent Calder and Michael Kotler eds., The Ideas Industry: Comparative Perspectives, Johns Hopkins University, Washington DC 2015. A student of John F. Howes, historian of Meiji samurai Christian converts, Horvat has had a long-standing interest in Nitobe Inazo. In 2004, as Japan representative of the Asia Founda-tion, Horvat convened symposiums on Nitobe’s lasting popularity among Japa-nese leaders and intellectuals.E-mail: [email protected]

Tinka DELAKORDA KAWASHIMA holds a PhD in sociology from the Uni-versity of Ljubljana, Slovenia. She earned her MA degree in religious studies from University of Tsukuba, Japan, and BA degrees in Japanese and Chinese studies from the Department of Asian Studies, University of Ljubljana. She is currently a lecturer in intercultural studies at Yamaguchi Prefectural Univer-sity, Japan, and a research associate of the Department of Asian Studies, in the University of Ljubljana. She has published a monograph on Religiosity and Consumption in Contemporary Japanese Society (ZRC SAZU, 2015, Ljubljana; in Slovene), and various articles relating to pilgrimage, religious tourism, her-itization processes, and the construction of sacred places in Japan and central Eastern Europe.E-mail: [email protected]

41

Naama EISENSTEIN is a PhD candidate in the History of Art and Archaeology Department of SOAS, University of London. She holds two MA degrees: From the East Asian Studies Department, Tel Aviv University, Israel, where she studied visual representations of sacred locations focusing on Nachi Waterfall, and from SOAS, where she examined nineteenth-century portraits of Nichiren. In her PhD research she studies warrior culture as it is represented in early modern Japanese artwork, focusing on the image of the Genpei War during the Edo Period.E-mail: [email protected]

Karl FRIDAY is a Professor Emeritus, Center Director, PhD (History) 1989, Stan-ford University. He has taught in many renowned universities around the world, most recently at the University of Georgia, Athens, where he has been Professor Emeritus since 2012. Since 2010 he has also been a director of the IES Abroad Tokyo Center. He has written many books, articles and book chapters, edited many volumes on the topics of history, martial arts, samurai, bushidō in Japan and world-wide. Toname just a few: Hired Swords: The Rise of Private Warrior Power in Early Japan in 1992, Legacies of the Sword: the Kashima-Shinryū & Samurai Martial Cul-ture, with Prof. Seki Humitake in 1997, and The First Samurai: The Life & Legend of the Warrior Rebel, Taira Masakado in 2008, among many others.E-mail: [email protected]

Klara HRVATIN completed her master’s and doctorate studies at Osaka Uni-versity (Musicology and Theater Studies), and is presently working as an assis-tant-researcher at the Department of Asian Studies at the Faculty of Arts in Ljubljana. Her focus is mainly on topics related to the composer Tōru Take-mitsu and Sōgetsu Art Center, Japanese contemporary music, Japanese per-forming arts and theatre, and Slovenian popular music. E-mail: [email protected]

Ryan JEPSON is a human geographer, sociologist, aikido teacher and learner, and current PhD student and research assistant at the University of Vienna, Austria (since 2015). His research interests include: practice theory and action research, spatial theory and practice, everyday life and rhythmanalysis, urban commons, globalisation and migration, and the sociology of art. His PhD pro-ject is applying Rhythmanalysis (H. Lefebvre) firstly to institutional settings – understood as a set of practices – with a focus on the provision and everyday management of refugees in Vienna, and informal networks of socialisation and their role in producing affect and everyday spaces of inquiry.E-mail: [email protected]

42

KAWASHIMA Takamune received his PhD degree from the University of Tsukuba, Japan. He was awarded the title of Docent in Slovenia, while he was teaching Japa-nese history, culture, and language at the Department of Asian and African Studies at the Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, from 2009 to 2012. After working at the University of Tsukuba from 2012 to 2013 as a research fellow, he now works at the Archaeological Museum of the Yamaguchi University, which conducts archaeo-logical excavations on the university campuses as well as organising exhibitions.E-mail: [email protected]

Nathan Howard LEDBETTER is a PhD student in Japanese history in the East Asian Studies Department at Princeton University in Princeton, NJ, United States. In his previous career as an officer in the U.S. Army, he worked as a liaison and policy analyst in Northeast Asia in addition to undertaking several tactical assign-ments. His current research examines the evolution of Japanese warfare and the or-ganization of military power over the course of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.E-mail: [email protected]

Simona LUKMINAITĖ read Japanese Studies (2008-2012) at Manchester Univer-sity, UK, where she received a BA (Hons) degree. In Osaka University, Japan, she received an MA in Studies in Japanese Language and Culture (2012-2014), with this work now continuing in the same specialty in her PhD studies (2014-present). She has worked at Kansai International High School as an instructor (2014-2016) and at Osaka University as a research assistant (2013-2017). Her areas of specializa-tion include the history of education, intellectual history, and history of religion in Japan, as well as women’s history, literature, and translation in this context. Her main research topic is Meiji ideologies regarding women’s education and the modern system of education in Japan.E-mail: [email protected]

Claudia MARRA is a professor of German and Japanese Studies and director of the Multimedia Center for Research and Education at Nagasaki University of Foreign Studies. Her research topics are the history of thought, aesthetics and religion in the Edo period. Her publications include 'Fucha Ryōri - the Monastic Cuisine of the Ōbaku-shū', 'Ōbaku’s Shōfukuji-temple', 'The Influ-ence of Chinese Thought on Ōbaku Zen Buddhism: About the discovery of “in-ternal organs” hidden inside Ōbaku's seated Shakyamuni statues', 'Haibutsu Kishaku', and 'Through Hanjimono to Enlightenment - The Pictural Heart-Sūtra.’ Marra has studied martial arts for more than 40 years, holding Dan-grades in jūdō, shotōkan karate, kendō and jōdō.E-mail: E-mail: [email protected]

43

Danny ORBACH is a military historian and senior lecturer in the Depart-ments of History and East Asian studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He studied in the universities of Tel Aviv, Tokyo and Harvard, where he also re-ceived his PhD. His latest books are The Plots against Hitler (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) and Curse on this Country – the Rebellious Army of Imperial Japan (Cornell University Press). He is currently studying the history of military ad-venturers in China from the Taiping Rebellion to the Second World War. As a political blogger, he writes regularly on political and military questions in the Jerusalem Post, War on the Rocks and other venues.E-mail: [email protected]

Jari Matti RENKO has practised and instructed koryu bugei with the Kashima-Shinryū of Helsinki University (Kashima-Shinryū Helsinki Shibu, an affiliate branch of Helsinki University Sports Institute) since 2005. He holds a Kaiden-ranking from Kashima-Shinryū. He works as the Chief Technology Officer at Oy Apotti Ab, where his main professional topic is the information enabled transformation of healthcare, both in preventative and social medicine as well as hospital care. His primary research interests include technology-assisted be-havioural change supporting population level preventive medicine.E-mail: [email protected]

M. Teresa RODRÍGUEZ-NAVARRO is an Associate Professor of Japanese Lan-guage and Culture. University of Granada, Spain. She is a member of Interasia Research Group, of the Autonomous University of Barcelona. Her research inter-ests include the influence of Japan on the West, especially in a Spanish context, and she is also a translator and writer. She has also worked as an intercultural mediator between Japan and Spain for more than 30 years in various different fields (like the arts, law and business). In her doctoral thesis, she worked on the figure of Nitobe Inazo as a bridge between East and West, focusing on the analy-sis of his work Bushido. The Soul of Japan, which she has also translated. E-mail: [email protected]

SEKI Humitake is Professor Emeritus of the Institute of Biological Sciences at the University of Tsukuba, and is the nineteenth generation Shihanke (head-master) of the Kashima Shinryū.E-mail: [email protected]

44

Jernej SEVER received his PhD from the University of Ljubljana. The main goal of his PhD research was understanding the connection between body pos-tures and higher cognitive processes in the martial arts. Jernej Sever is a di-rector of a Sport Center Premik in Ljubljana, and the head coach and leader of the Karate Institute in Slovenia. He is also responsible for the education program for coaches in the Karate Association of Slovenia, and runs workshops and seminars on the issue of how to cope better with stress, using various physi-cal techniques with the aim of creating a physical and emotional balance. E-mail: [email protected]

Aldo TOLLINI studied Japanese at the University Ca' Foscari in Venice, Italy. His interests are medieval Japanese culture, especially Buddhism, the culture of tea, and the translation of classical Japanese texts. He has published books such as Antologia del buddhismo giapponese (2009), Lo Zen. Storia, scuole, testi (2012), La cultura del Tè in Giappone e la ricerca della perfezione (2014) and L'ideale della Via (2017).E-mail: [email protected]

Mikko VILENIUS received his PhD from the University of Electro Commu-nications, Tokyo, Japan in 2012. His thesis topic was supporting collaborative learning activities in informal learning on-line. He has been working as a re-searcher in educational technology since 2010, first in the Japan Institute of Educational Measurements, and later in EduLab, Inc. Dr Vilenius has been living in Japan for over 10 years, and actively practising Kashima-Shinryū. He has received the rank of menkyo-kaiden and is recognised as an official instruc-tor by the Kashima-Shinryū Federation of Martial Sciences.E-mail: [email protected]

Nataša VISOČNIK earned her degree in ethnology and cultural anthropology and Japanese studies from the University of Ljubljana. In 2009 she received her PhD from the Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, from the Faculty of Arts at the University of Ljubljana. She is currently an Assistant Professor at the Department of Asian Studies at the same university. She has published a monograph on housing and identity in Japan, A House as a Place of Identity (2011), and various articles relating to identity, the anthropology of space and body, and minority issues in Japan. E-mail: [email protected]

45

Mateja ŽABJEK is doctoral student at the Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, the University of Tsukuba, Japan. Her research field is sociology and religious studies, and more specifically religious traditions and practices and their influence on Japanese martial arts.E-mail: [email protected]

Ari YLINIEMELÄ is a graduate from the University of Helsinki, Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry. He started Kashima-Shinryū training in Japan in 1992, and was awarded the rank of menkyo-kaiden in 2009. He works at the Finnish subunit of the Phoenix Group, responsible for the analysis, planning and execution of development projects related to the EU Falsified Medicines Directive.E-mail: [email protected]